Essays

The problem of free will becomes especially sharp when placed alongside modern physics and contemporary philosophy of language. If the laws of nature together with the complete state of the universe at some past time fix everything that ever happens, then in what sense could anyone have done otherwise? Yet at the same time, developments in epistemology and metaphysics suggest that our experience of openness may reflect deep features of our epistemic situation rather than metaphysical indeterminacy. To understand this landscape, I propose to bring together four figures whose work illuminates different aspects of the issue: Tim Williamson on epistemic vagueness, Roy Sorensen on blindspot ignorance, Barry Loewer on the Mentaculus and objective chance, and Kit Fine on hyperintensional modality. We can then place their positions within a broader framework inspired by Rudolf Carnap and later refined by David Chalmers, before finally asking what an omnipotent God would know, and whether such a being would “see” free will.

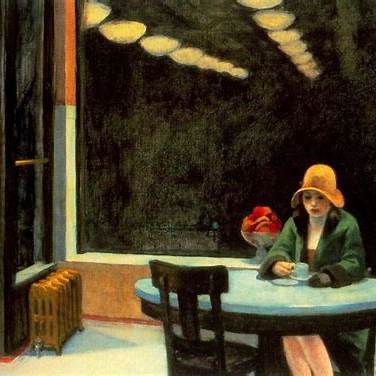

Read MoreWhat we see is a seated figure, recognisably human, but immediately fractured by a set of substitutions. The face is not a face but a mask, exaggerated, theatrical, already a kind of prosthesis. In front of that mask, held where a face would ordinarily present itself to the world, is a smartphone screen displaying a bright circular image. Below, between the legs, a red light glows, unnatural in colour and placement, irradiating the body from an interior zone that is neither clearly sexual nor clearly mechanical. The hands are raised to the head in a gesture that could signal distress, concentration, possession, or calibration. The body is still, but the image hums with incompatible functions.

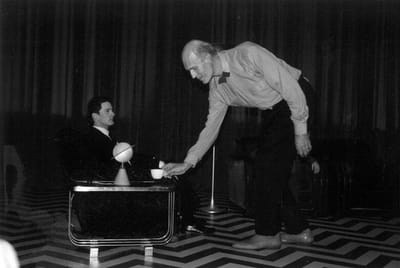

Read MoreCooper’s final move in Twin Peaks: The Return is the attempt to “fix” Laura by going back and pulling her out of the night. You can say, in an ordinary psychological way, that it is grief, guilt, saviour fantasy, trauma, a refusal to accept loss. All of that may be true. But it does not touch the more unnerving feature of the series, the sense that the reasoning itself, the “if I do this, then that will be restored” structure, becomes strangely unreliable, as if the very act of making the plan precise introduces a kind of loop, a silent snapping-back to the beginning.

Read MoreMost of us have had moments where we can feel, in our own lives, the pull of a counterfactual, the kind that starts to reorganise the air in the room. One is the aftermath of a relationship that really was love, and then stopped being love, or stopped being anything you can stand to name. After it ends, you find yourself trying to work out what would restore it. You replay a particular evening, a particular sentence, the moment you did not call back, the moment you did. You tell yourself, if I had been calmer, if I had been more honest, if I had not said that, if I had said the other thing, it would have held.

Read MoreKit Fine’s way into modality begins with a refusal. Most philosophers try to explain essence in modal terms. To say what something is, they ask what it could or could not be. Fine reverses the direction. He argues that what is necessary is necessary because of what things are. Essence is not a shadow cast by modality, modality is a consequence of essence. That reversal matters because it changes what we are doing when we talk about possibility. On the usual picture, you start with a space of possible worlds and then you see what happens to an object across them. On Fine’s picture, you start with the object, or event, or state of affairs, as the thing it is, and you ask what follows from that nature. The necessity you get is the thick metaphysical kind where the world is constrained by what this thing, as this thing, is.

Read MoreNaido in season three is the same being as the woman Cooper encounters in the Lodges in the original series, the figure often referred to as Ronette’s double, the eyeless woman, or simply the mute woman. However, season three deliberately reframes what that identity amounts to. The continuity is not psychological or biographical. It is ontological and functional.

Read MoreMr C functions as the clearest embodiment of what agency looks like once grounding has collapsed but instrumental power remains intact. If Dougie shows how a subject can persist without understanding, and the FBI shows how understanding can persist without efficacy, Mr C shows how efficacy can persist without responsibility, coherence, or even integrity. He is the season’s most ruthless figure because he is perfectly adapted to the world episode eight reveals.

Read MoreEpisode nine marks a subtle but decisive shift. After the ontological violence of episode eight, which stripped the series down to its deepest conditions of possibility, episode nine returns us to the everyday world, but that return is now charged with a new clarity. Nothing has been repaired. Nothing has been explained. What has changed is that the series now begins to show, in more recognisable narrative terms, how life proceeds once the damage exposed in episode eight has already been absorbed. If episode eight was the rupture made visible, episode nine is the world learning how to move on inside it.

Read MoreThe standard critical move is to treat the “planet” sequence and the lever pulling figure as either (i) symbol, (ii) dream image, (iii) projection of Henry’s psychology, or (iv) a deliberately underdetermined flourish whose point is affect. Those approaches thin the ontology. They either collapse what we see into a code for something else, or they treat it as a way of presenting an inner state. Either way, the strange creature is not something over and above Henry’s predicament, it is a representational device.

Read MoreWhat is the “matter” out of which the person on screen is composed, bodies, voices, clothes, rooms, names, memories, institutional roles, photographs, and who designates which parts count as spatial parts and which as temporal parts. In the college example, the fellows can be temporal parts without fixing the college’s location. In film terms, a character’s lovers, fears, and humiliations can be temporal parts of the character, without being spatially where the character is. That is banal in life, but Lynch makes it visible.

Read MoreFine’s approach, condensed into a working set of lenses, is a disciplined generosity about what kinds of things there are, and about how the same underlying “stuff” can support more than one object, depending on the form, the structuring, the mode of presence, and the relevant perspective. Fine treats hylomorphism as a method, a thing is a compound of matter and form, where matter is the underlying base, people, buildings, artefacts, and form is the structuring relations and rules that make that base count as a committee, a college, a country.

Read MoreSo I've written far too much about contemporary analytic metaphysicians Timothy Williamson and Kit Fine and their respective approaches to modality, attempting to understand their claims via the lens of Lynch's films (and vice versa). I'll assume some of this has been absorbed. So, if we now let this Finean way of thinking about bodies, embodiment, and form range freely across the Lynch films already in play, Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, and Inland Empire, a unifying pattern emerges that is deeper than narrative fragmentation, dream logic, or psychoanalytic allegory.

Read More