A Turd in the Punchbowl: Initial Thoughts On Christoph Shuringa’s A Social History of Analytic Philosophy Or: An epigone Crashes the Party

By EJ Spode

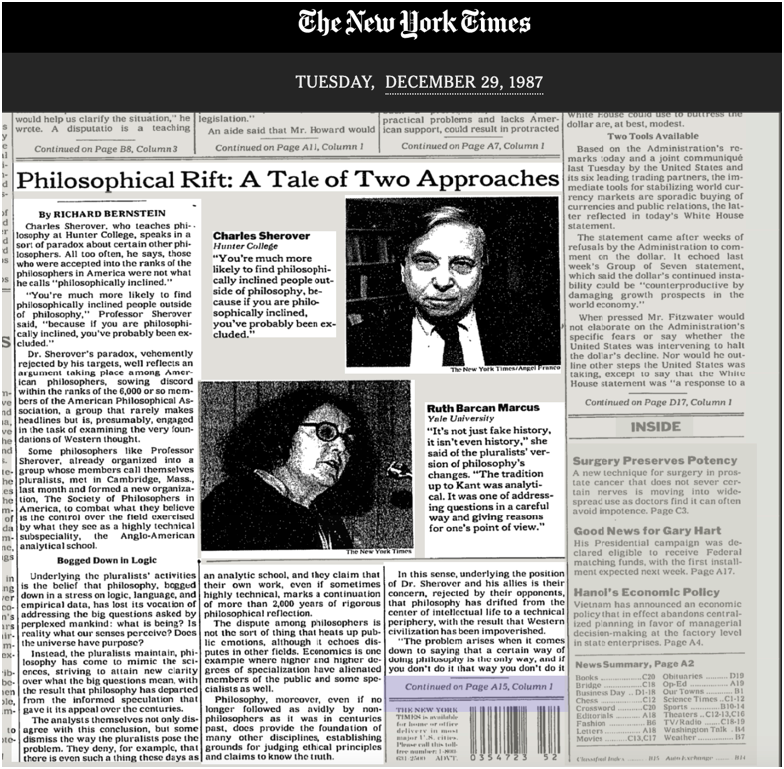

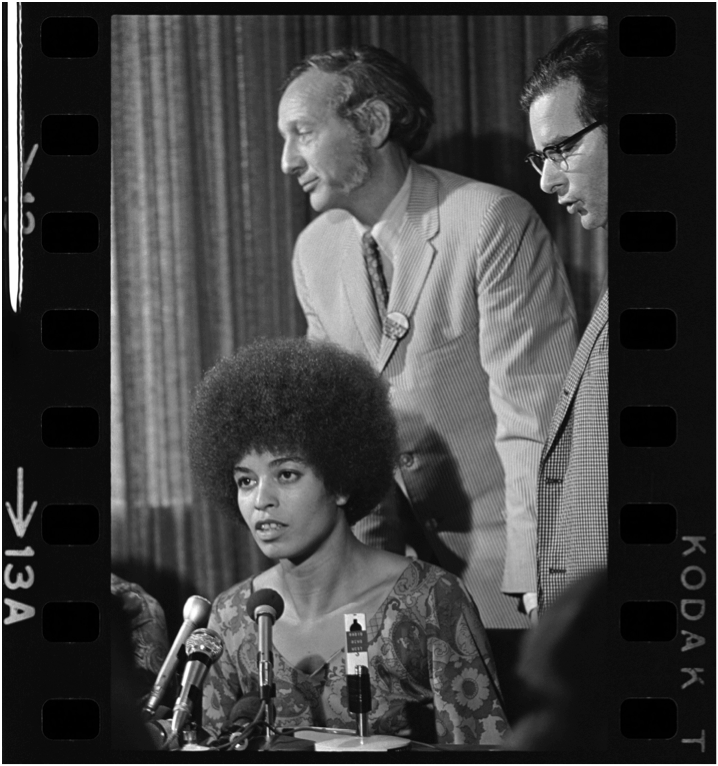

When I was first hired as a junior professor of philosophy in 1987, I joined a department (at Stony Brook University) that had three “wings” – one in continental philosophy, one in systematic philosophy, and one in analytic philosophy. This demarcation was a reflection of a schism in 20th-century that even then, was not making very much sense. I was already unclear what the distinction even came to. It’s not like there was some doctrine that continental philosophers believed that analytic philosophers didn’t or couldn’t. It was more of a sociological distinction having to do with your professor’s professor’s professor, who you read, and what your style of communication was like.

Originally, as we will see, the rift had quite a lot to do with Jewish analytic philosophers fleeing Europe during World War II, and finding safe havens in United States universities. Understandably, they were not fans of Continental philosophers like Martin Heidegger, who had been completely in the tank for Hitler, and they were particularly put off by claims that analytic philosophy was “bloodless” or “ungrounded in culture.” They had heard that one before, albeit in another context. This led to some unfair blowback against continental philosophers in general, which led to unfair blowback against analytic philosophers in general, and on and on it went until people decided that enough was enough (more on this later).

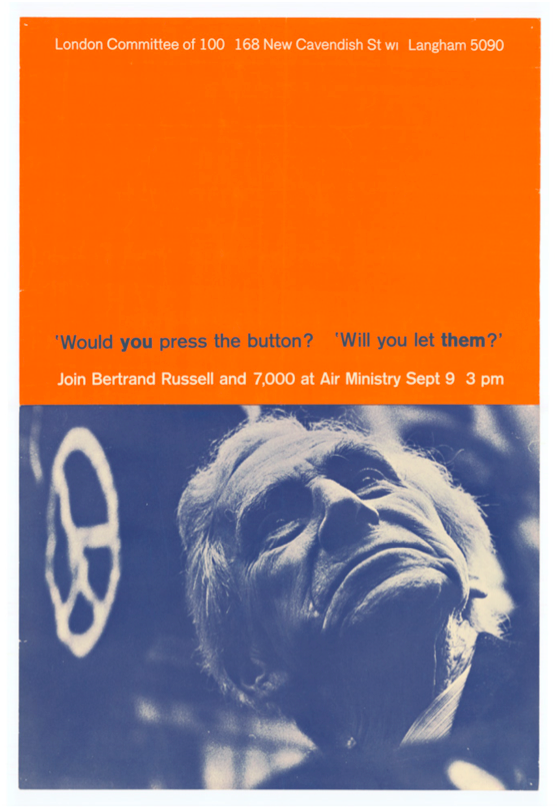

By 1987, for sure, some retirement-age philosophers held ancient grudges, but even in the case of the professors who had been victims of the Analytic/Continental wars (e.g., the purges of Continental philosophers at Yale), the victims were ready to let bygones be bygones. There were bigger fish to fry in the age of Ronald Reagan.

Indeed, by the late 1980s, continental philosophers and analytic philosophers were discovering that they had quite a lot in common, including a shared mandatory reading list that spanned well over 2300 years of philosophical common ground. It should come as no surprise that the common ground extended beyond shared background literature. They were apt to find themselves closely aligned politically and socially, and on pretty much anything, including (surprisingly often) who the smart students were, who the better teachers were, and where the best food was near campus.

If it seems that I am painting a kumbaya moment, well, perhaps I am. It was like a freshman mixer, with people from diverse backgrounds getting together for the first time and finding out, while they stood over the punch bowl, that they had much in common.

Apparently, not everyone has been enjoying this kumbaya moment – certainly not Christoph Schuringa, who has recently stepped into this happy freshman mixer and dropped a giant turd into the punchbowl, in the form of his new book. A Social History of Analytic Philosophy.

The book’s central thesis is that analytic philosophy was born into economic privilege and that it has been carrying water for the status quo ever since. It has been a force defending bourgeois liberal ideology and marginalizing radical alternatives like Marxism. It is somehow a cheerleader for colonialism and capitalism. These are also the messages that readers of the book are getting. So, for example, Žižek’s takeaway from the book is that “analytic philosophy is not politically neutral, it is deeply rooted in capitalist liberalism and its struggle against Leftist engagement.” Adam Knowles, in Radical Philosophy, takes the point to be that analytic philosophy is “an intellectual tradition harbouring colonial ambitions.” He adds that “Schuringa produces a persuasive case for analytic philosophy’s fundamental role as a powerful intellectual tool of bourgeois liberal ideology.”

Schuringa not only has a thesis, but he also wants us to know that he is not messing around. He is serious!

The tradition of empiricism-liberalism represented by Hume, continued by analytic philosophy in spite of its ignorant self-image as just philosophy as such, rightly trembles at the wrath that might be unleashed by the powerful critical forces that its hegemony helps to keep suppressed.

Wowzers, that quote is some Conan-the-Barbarian smack talk, but my first thought was: Hume? What? In any case, I thought I might take some time off from my trembling and write some thoughts about Schuringa’s book.

And my point here, now, is that for better or for worse, analytic philosophers have been at the vanguard of progressive and radical social movements since it was forged in early 20th Century Vienna and Cambridge University, it retained its radical socio-political edge through the Cold War, and it retains that radical edge today. My more important point is that we are approaching an “all hands on deck” moment, and it is critical that analytic and continental philosophers need to unify in countering the very real dark forces that are at work in the politics of today.

The Myth of Socially Disconnected Analytic Philosophy

Let’s be clear on what the claims on the table are. One claim is that analytic philosophy is ahistorical and uninterested in anything that has to do with the social or political. It is, by virtue of this alleged disinterest, that it can serve as a tool of liberal bourgeois ideology. As Schuringa puts it in the opening line of his book:

Analytic philosophy, today the hegemonic form of academic philosophy in the English-speaking world and beyond, tends to think of itself as removed from the changing scenes of history. It acts as if it were pursuing its questions from a vantage point situated nowhere in particular, unaffected by social and political reality. It thus operates as a tradition that manages to think of itself as no tradition at all.

Later, he says that this ahistorical, disconnected perspective can be found in the very style of analytic philosophy and the topics that it engages.

The analytic style is highly ahistorical and acultural. ... Analytic philosophy tends to remain ignorant of large bodies of theory, particularly those concerned with culture, politics, anthropology, psychology, sexuality, religion, literature, and so on.

Neither of these claims are true of analytic philosophy as it is. They are not even true of analytic philosophy in its origins. As Schuringa surely knows, the founding document of analytic philosophy – the manifesto of the Vienna Circle, speaks directly to this point. Consider, for example, the concluding paragraph of that manifesto.

Thus, the scientific world-conception is close to the life of the present. Certainly it is threatened with hard struggles and hostility. Nevertheless there are many who do not despair but, in view of the present sociological situation, look forward with hope to the course of events to come. Of course not every single adherent of the scientific worldconception will be a fighter. Some, glad of solitude, will lead a withdrawn existence on the icy slopes of logic; some may even disdain mingling with the masses and regret the ‘trivialized’ form that these matters inevitably take on spreading. However, their achievements too will take a place among the historic developments. We witness the spirit of the scientific world-conception penetrating in growing measure the forms of personal and public life, in education, upbringing, architecture, and the shaping of economic and social life according to rational principles. The scientific world-conception serves life, and life receives it.

This does not sound like people who are “ahistorical” (to the contrary, their “world-conception is close to the life of the present.”). Nor does it sound like people who are “situated nowhere in particular, unaffected by social and political reality.” To the contrary, they say that their world-conception is penetrating “the forms of personal and public life, in education, upbringing, architecture, and the shaping of economic and social life,” albeit according to “rational principles,” which may be the thing that Schuringa is really objecting to.

Now Schuringa knows that this is the, or at least a, founding document of analytic philosophy, but here and elsewhere he deploys a strategy of deception that he will conduct for some 330 pages, in which he acknowledges what he must (although, if he can get away with it, he will suppress it), and then spin up a story that the person in question was not really saying what they appear to be saying and doing. He will downplay the radicalism of radicals, and he will downplay the social engagement of the socially engaged. The end result is an astoundingly dishonest document, from its very first page to the last. I understand that that sounds harsh, but hear me out. We are going to walk through this book, claim-by-claim, defamation-by defamation, deception-by-deception, to try and sort this out.

What I intend to show is that, counter to Schuringa’s claims, it is absurd to say that analytic philosophy is ignorant of “culture, politics, anthropology, psychology, sexuality, religion, literature.” It is absurd to say that analytic philosophy has recoiled from radical and revolutionary political thought. Analytic philosophy has been engaged with all of these topics from the beginning. And the place we will start is with the Vienna Circle.

There is this mythology about the positivists that they were caught up in logic, and the language of science and nothing else. But the positivists, living in early 20th-century Vienna, were neck deep in the culture, politics, anthropology, psychology, etc. of their age. They were key figures in the culture of their age, and they were working to find a way forward in the post-World War I wreckage of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This is clear from Philipp Frank’s list of people they were reading: Franz Brentano, Alexius Meinong, Hermann von Helmholtz, Heinrich Hertz, Edmund Husserl, Sigmund Freud, Bertrand Russell, Alfred North Whitehead, Vladimir Lenin, and Gottlob Frege. Despite the press they get, the members of the Vienna Circle were interested in everything.

To give just one example, members of the Circle had regular contact with the Bauhaus artists in Berlin. Otto Neurath was invited to the opening of the New Bauhaus in Dessau. Herbert Feigl and Rudolf Carnap also lectured there, and all were directly engaged with avant-garde artists of the age – Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers.

As Peter Galison notes in an article on their connection, the Vienna Circle and the Bauhaus were also drawn together by their common enemies: “the religious right, nationalist, anthroposophist, völkisch, and Nazi opponents.” Everyone knows the story about how Jewish artists and philosophers had to flee the Nazis, but I don’t think most people appreciate what they were actually up against philosophically. And the best way to illustrate this is in the case of the assassination of Circle leader Moritz Schlick and the aftermath of his assassination.

Schuringa is not impressed by the manifesto of the Vienna Circle, and he points to the carve-out in the final paragraph, for people who “lead a withdrawn existence on the icy slopes of logic.” But as we will see, even the members of the Circle who were not political, who led a “withdrawn existence on the icy slopes of logic,” were, in the context of their times, inherently political. There is no better illustration of this than the death of Moritz Schlick, who did not self-identify as one of the political members of the Circle. But in context, he was very much politically engaged. And sadly enough, the place where we can best see this is in his assassination in 1936.

The Death of Moritz Schlick

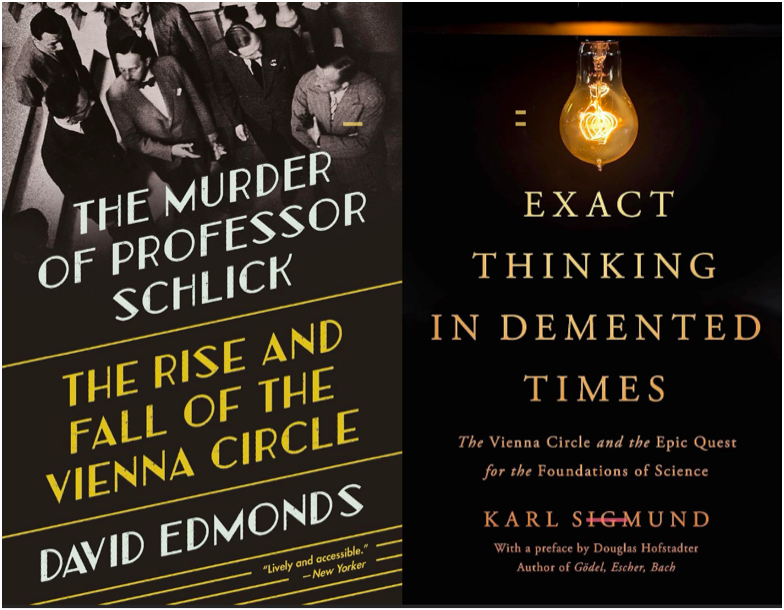

All Schuringa says about this critical event is that “Schlick was murdered by a mentally ill student in 1936.” Full stop. And well, the student probably was mentally ill, but it ignores the way that the right-wing press in Vienna celebrated Schlick’s murder. His murder, and the response to it in the press, are illuminating, for they show the kind of world that the Vienna Circle was inhabiting, how completely radical they were in that context, and the horrific abuse they had to endure because of their philosophical stance. It is somewhat surprising that Schuringa skips this event entirely, as I would have thought they would be the centerpiece of any social history of analytic philosophy.

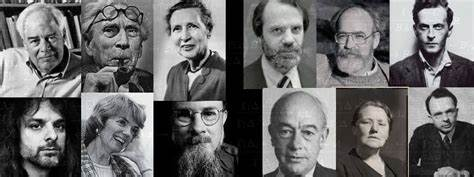

There are two very fascinating books about this topic: by The Murder of Professor Schlick: The Rise and Fall of the Vienna Circle. (Princeton, 2020), by David Edmonds, and Exact Thinking in Demented Times, by Karl Sigmund.

As both books report, there was a cascade of articles in the local Vienna media, using the murder of Schlick to put the philosophers of the Vienna Circle on trial in the court of public opinion. The real victim, they seemed to be arguing, was the killer.

For example, on July 10, the Linzer Volksblatt ran an article condemning Schlick for corrupting "the fine porcelain of the national character." This bit is fleshed out by Sigmund, in Exact Thinking in Demented Times:

In the daily Linzer Volksblatt, one Bernhard Birk wrote about the problematic activities of Moritz Schlick: “For a full fourteen years, young, tender flowers of humanity were forced to drink from the poisonous vial of positivism as if it were the very water of life. The effect must have been horrible.” Robust souls would simply throw up, said Birk. However, “there also exist delicately organized minds, fragile porcelain from the roots of the Volk, patriotic children of the Austrian soil, people who yearn for the beautiful and the noble. To pour the doctrine of positivism into these wide-open minds is like pouring chloric or nitric acid down their throats.”

Two days later, in the intellectual weekly paper Schönere Zukunft (Better Future), came out with this:

The Jew is a born anti-metaphysician and loves logicality, mathematicality, formalism, and positivism in philosophy—in other words, all the characteristics that Schlick embodied to the highest degree. We would like to point out, however, that we are Christians living in a Christian German state, and that it is up to us to determine which philosophy is good and appropriate.

This was followed by a lengthy article under the pen name “Prof. Dr. Austriacus”. Edmonds describes the thesis of the article as follows:

Nelböck (the killer) had been turned into a psychopath by Schlick's radically destructive philosophy. This loathsome philosophy was antireligious and anti-metaphysical. The bullet that had killed Schlick was “not guided by the logic of some lunatic looking for a victim, but rather by the logic of a soul, deprived of its meaning of life.”

The Vienna Circle, the article continued, had come to be seen abroad as representing Austrian philosophy, “much to the disadvantage of Austria's reputation as a Christian state.” But Schlick had not pursued his philosophical project alone, of course. Among his collaborators was his “close friend,” the communist Otto Neurath.

As Edmonds notes, the article didn’t say that Schlick was Jewish (he wasn’t). But the assumption (or allegation) was plain. If not a Jew, Schlick was at the very least Jew adjacent; he was philosophically aligned with them. He represented a degenerate Jewish strain of thought. Among other charges directed at Schlick in the article was the claim that he had Jewish research assistants (Friedrich Waismann and two Jewish women). The article concluded that while killing was not strictly speaking a good thing, perhaps some good would come from the killing:

Let the Jews have their Jewish philosophers at their Cultural Institute! But the philosophical chairs at the University of Vienna in Christian-German Austria should be held by Christian philosophers! It has been declared on numerous occasions recently that a peaceful solution of the Jewish question in Austria is also in the interest of the Jews themselves, since a violent solution of that question would be unavoidable otherwise. It is to be hoped that the terrible murder at the University of Vienna will quicken efforts to find a truly satisfactory solution of the Jewish Question.

Prof. Dr. Austriacus is believed to have been Johann Sauter, a philosopher at the University of Vienna, a Kantian, a Nazi, and an ally of Othmar Spann, the ultranationalist sociologist and economist.

It is not surprising that Schuringa would want to bury all this, as his own critique of analytic philosophy reads as if it were cribbed from those articles celebrating the death of Schlick. All you have to do is replace the word ‘Jew’ with the phrase ‘analytic philosopher’: “The [analytic philosopher] is a born anti-metaphysician and loves logicality, mathematicality, formalism, and positivism in philosophy.”

Once again, Schuringa glosses all of this as “Schlick was killed by a mentally ill student.” Full stop. That’s your social history.

Murder on the Philosophers’ Staircase

Staircase where Schlick was assassinated

The Vienna Circle takes on the German Philosophical Society

While we are in the business of context-setting, let’s back up a few more years and further contextualize Schlick’s murder. As we will see, there were some broader events that help to explain how we got to where we are with the analytic/continental split, and a lot of that split has to do with the nature of philosophy in the German-speaking world in the 1930s. That brand of philosophy was not in a good place, and a great conflict was already in motion by 1933. Here is how Peter Galin described the philosophical events of that year.

With both Marxists and positivists on the run, the German Philosophical Society celebrated the Nazis' election to power. Their meeting of October 1933 opened with the collective singing of the "Deutschland Lied" and "The Horst Wessel Song." Now, the Nazi representative proclaimed, philosophy would be applicable to the people and fulfill the spiritual needs of the Volk. Hitler telegraphed a laudatory greeting, part of which read: “May the forces of true German philosophy contribute to the building and strengthening of the German worldview.” The philosophers complied with talks on Deutschtum, Volk, Soul, and Spirit.

A month prior to this conference, Martin Heidegger had been named rector of Freiburg University. Not only did he publicly celebrate his joining of the National Socialist Party, but he even took to lecturing while wearing a Nazi stormtrooper brown shirt. Heidegger declared, “Adolf Hitler, our great leader and chancellor, with his National Socialist revolution, has created a new German state, which will safeguard for its people the stability and continuity of its history. Heil Hitler!” (Heidegger, early August 1933, in Collected Works, vol. 16, 151)

About that storm trooper brown shirt -- the Sturmabteilung (aka “storm division,”) shirt: In case you forgot, Wikipedia will remind you that the business of the Sturmabteilung was, “protection for Nazi rallies and assemblies, disrupting the meetings of opposing parties, fighting against the paramilitary units of the opposing parties, especially the Roter Frontkämpferbund of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), and intimidating Romani, trade unionists, and especially Jews.”

People sometimes argue that Heidegger was just being opportunistic here, and wasn’t really a Nazi Nazi (despite the brown shirt), but this is altogether too charitable. He was clearly in the tank for Hitler two years earlier, as the following Christmas letter to his brother’s family shows.

18th of December, 1931Dear Fritz, dear Liesl, dear boys,

We would like to wish you a very merry Christmas. It is probably snowing where you are, inspiring the hope that Christmas will once again reveal its true magic. I often think back to the days before Christmas back at home in our little town, and I wish for the artistic energy to truly capture the mood, the splendor, the excitement and anticipation of this time.

[…]

It would appear that Germany is finally awakening, understanding and seizing its destiny.I hope that you will read Hitler’s book; its first few autobiographical chapters are weak. This man has a remarkable and sure political instinct, and he had it even while all of us were still in a haze, there is no way of denying that. The National Socialist movement will soon gain a wholly different force. It is not about mere party politics—it’s about the redemption or fall of Europe and western civilization. Anyone who does not get it deserves to be crushed by the chaos. Thinking about these things is no hindrance to the spirit of Christmas, but marks our return to the character and task of the Germans, which is to say to the place where this beautiful celebration originates.

Heartwarming.

These developments were the backdrop for the events of 1934, in which many of the Nazi philosophers from the German Philosophical Society would collide with the members of the Vienna Circle at the International Philosophy Congress in Prague, in a pivotal event in the history of analytic philosophy and one which of course is mentioned nowhere in Schuringa’s book. The Vienna Circle crew arrived in Prague, and they were ready to drop the hammer on the Nazis. Here is how Galison (1990) described the event.

Less than a year later, when the Vienna Circle confronted the right-wing philosophers at the International Philosophy Congress in Prague, a clash was inevitable. The principal nationalistic philosophy journal reported excitedly that the Congress had revealed philosophy to be at a turning point, as “a certain Volk” took its place in the development of the World Spirit. One of the heroes of nationalist philosophy, Hans Driesch, presented a plenary lecture, arguing for vitalism and guarding a place for metaphysics. [Driesch would soon be retired for not being Nazi enough.]

Here the Vienna Circle jumped into the fray with what its enemies characterized as a “vehement and well organized attack,” in which the Circle decried metaphysics as meaningless. Viewed from the right, the positivists “stood in the way” of the metaphysical concept of the world that was to underwrite the German worldview. Reichenbach blasted Driesch’s organicism as “mystical,” while Carnap denied that Driesch's organicism was sufficiently lawlike to make it scientific. Schlick remained silent, but the next day he presented an entire lecture, “On the Concept of the Totality,” in which he claimed that while the distinction between totalities and aggregates might be linguistic or pragmatic, it was not a substantive distinction: there was no whole over and beyond the sum of parts.

Schlick’s paper was abstract on the face of it – something about totalities vs aggregates. But his message was quite clear. There was no Germany above and beyond the individual Germans. People should not be submitting themselves to an abstract metaphysical concept of Germany. Perhaps, to our eyes, his work wasn’t political. To our eyes it was just some shit about totalities and aggregates. But, in that context, it was the most political thing you could possibly say. And hang on to that thought, because it is not always clear what is political and what is not. You cannot make that distinction in a vacuum.

People sometimes want to say that the Naziism of philosophers like Heidegger was distinct from their philosophy. But the members of the Vienna Circle saw it another way. In their view, this was what you got when you started trafficking in metaphysical notions and started talking about abstracta like the Volk. It was a natural outcome of such views. They had been warning people about it for years. Fuck around with metaphysics and find out. It wasn’t just internally bad philosophy. It was bad because of what it led to politically and socially.

In this context, it is obviously absurd to suggest that the members of the Vienna Circle were “ahistorical.” They very much knew their place in the history of Europe, and they very much knew that they were at a historical inflection point. They also knew that their philosophical reflections were not inert in their times. They couldn’t be. Thus, when Schuringa says that analytic philosophy “tends to think of itself as removed from the changing scenes of history. It acts as if it were pursuing its questions from a vantage point situated nowhere in particular, unaffected by social and political reality,” what he says is not true. It was not true of the members of the Vienna Circle. Nor, as we will see, would it be true of subsequent analytic philosophers.

Of course, Schuringa’s central project is not to claim that analytic philosophy is merely culturally inert, but also that it is politically conservative – that it is in the bag for the liberal capitalism. As we will see, this claim is false, and it is certainly absurd when applied to the members of the Vienna circle. Many members of the circle were socialists, including Otto Neurath, Rudolph Carnap, Philipp Frank, Edgar Zilsel, and Hans Hahn. The founding manifesto of The Circle name-checked the Austro-Marxists Otto Bauer, Rudolf Hilferding, Max Adler. They, and the Circle’s socialists (Neurath et al.) were co-inhabitants of Red Vienna’s institutions – party press, adult education, municipal reform, Ernst Mach Society – sometimes directly interacting, always moving in the same tight ecosystem. Since Schuringa defames these philosophers individually, we will address those defamations individually, and we begin with the case of Otto Neurath.

Otto Neurath

Above all, the fight against metaphysics and theology means the destruction of bourgeois ideology.

--- Otto Neurath, Empirische Soziologie, 1931

Otto Neurath and icons from his ISOTYPE iconic language

Schuringa can’t deny that members of the circle were politically active, but he can downplay their political activism. Well, he can try anyway. For example, while everyone I know would identify Otto Nerath as a socialist, Schuringa isn’t having it. In his view, Neurath’s political project fell “short of even the most minimal precepts of socialism.” Hmmm, let’s see about that…

We can start with a little history. At the end of the First World War, in 1918, as the war turned against Germany, Kurt Eisner of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) mobilized antiwar protestors and then members of the army against the Bavarian government, and in so doing forced the abdication of King Ludwig III of Bavaria. Eisner became minister-president of the newly proclaimed Free State of Bavaria (or People's State of Bavaria). In 1919, Eisner offered Neurath a chance to pitch his economic ideas to an actual socialist government. Neurath thus traveled to a wildly turbulent Munich to meet with Eisner and his political party. There were bumps in that road.

On February 21, 1919, Eisner (who was planning to resign his position) was assassinated by right-wing extremist Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. Pandemonium broke out in parliament, shots were fired, and MPs fled through windows and down drainpipes. March 7, 1919, The Social Democratic Party (SPD) took control and nominated former schoolteacher Johannes Hoffmann as new leader. Hoffman appointed Neurath to his administrative position in the government. Officially, Neurath was Präsident des Zentralwirtschaftsamtes (President of the Central Economic Office). Then things got messier.On April 7, 1919, the Communisty Party (the KPD) and the USPD proclaimed the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, forcing Hoffman’s SPD government into exile. Neurath somehow convinced the new government that his office was “nonpolitical” and that he should stay on to carry on his economic work. A social activist and poet, Ernst Toller, was declared the new leader of the revolutionary government.

The new government consisted of the Central Council, dominated by anarchists and intellectuals; among them were anarchist writer Gustav Landauer, merchant Silvio Gesell, and playwright Erich Mühsam (we will return to all three shortly). Toller referred to the event as the “Bavarian Revolution of Love,” and his government became widely known as “the regime of the coffeehouse anarchists.” It lasted for six days.

On April 13, Toller's government was ousted in a putsch organized by the Communist Party (KPD). The new head of state was now Russian-German Bolshevik, Eugen Leviné. Back in Russia, Vladimir Lenin was delighted to get this news, and announced that “The liberated working class is celebrating its anniversary not only in Soviet Russia but in… Soviet Bavaria.”

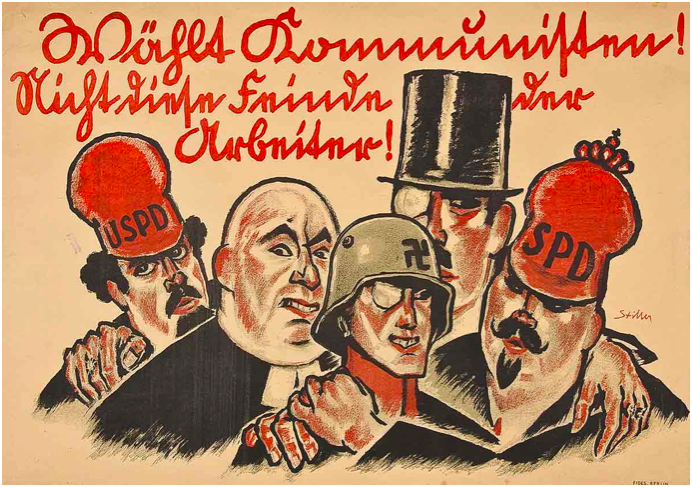

Vote communists![PDK] Not these enemies of the workers!

Neurath was still there, only now the communists gave him a promotion! Neurath was promoted to the Council of Ombudsmen, where he continued implementing his socialization plans, but now Gesell was placed underneath him to handle more pedestrian financial issues. Neurath was the economic planner now. On April 13, Hoffmann's SPD government-in-exile sent forces to Munich. The first armed clash occurred, resulting in 80 injured and 21 deaths, but Leviné’s PDK forces won. But then, on May 3, the German Army (under control of the SPD) came in and shut down the Bavarian Soviet Republic for good. It had lasted less than a month in total, with two distinct phases: Toller's anarchist-influenced government (6 days) and Leviné’s Communist government (about 3 weeks). Neurath was there for it all.The free state was abolished, and its leaders arrested or executed. Neurath was charged with being an accessory to treason and sentenced to eighteen months of confinement, although ultimately his sentence was commuted, and he was banished from Bavaria (I would say that is a win-win for Neurath).

This leaves us with the question of what Neurath was up to in his economic office, and the simplest way to put it is that he had definite ideas about how a socialist state could and should be organized. Here is how Thomas Uebel laid out Neurath’s economic project in a 2020 paper called “Intersubjective Accountability: Politics and Philosophy in the Left Vienna Circle.”

The politics at issue here are not simply the reformist policies of the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SDAPÖ) – which both Neurath and Carnap were members of – but much more radical schemes of social transformation. Importantly, what I here call Neurath’s socialization theory were his plans for the economic reorganization of society and their theoretical underpinnings – not whatever normative arguments may be used to agitate for these plans.

Neurath developed his socialization theory and promoted the associated program mainly in the years 1917–1921, so his involvement anticipated but also outlasted the revolutions in Germany and Austria at the end of World War One. At issue for him was a reorganization of the entire economy of a nation that did not concentrate on the appropriation of the ownership of the means of production by the workers’ state and their organs, but on the appropriation of the executive power to decide the use of these means of production. This meant the abolishment of the market and its “invisible hand” in coordinating the economic actions of state, firms and individuals. The economy was to become subject to a comprehensive plan by which the conditions of life of all members of the society were to be improved, and every enterprise within the economy was to play its designated role.

Neurath’s work differed from the socialism that we became accustomed to seeing in the 20th-century – top-down social planning in which elites in Moscow or some such place dictated how things were to be managed. Neurath had a different vision. He was a bottom-up socialist. The idea was to have planned economies, but to have the proletariat actually choose those plans. So, for example, the role of experts was not to decide and implement policy, but to present and explain options for plans that the people’s representatives would vote on. It then became critical for the planners to present the options in a way that everyone could understand. And this is where the pedagogical part of Neurath’s project came in, and this is what ultimately motivated his icon-base ISOTYPE system. It was part of his idea that planners needed to help workers make informed decisions. It is also a source for the demand for clarity in analytic philosophy, a theme we will return to later.

Again from Thomas Uebel:

Here we reach a point that is all too easily lost when we think of Neurath as a theoretician of planned economies and associate the latter only with the Soviet Union. There the economic plans were weapons of the vanguard party that made decisions for the proletariat. Neurath’s schemes, however, did not embody this top-down approach. Even though he generally bracketed questions of the organization of political power (a point on which he was criticized by fellow socialists) … his numerous economic organizational plans, varied for different audiences and circumstances of application, all have this in common: the planners had to submit their plans as proposals for evaluation and possible approval to the “people’s representatives.” The experts did not have the last word: their role was to show what was doable, but they did not make decisions about what was to be done. Neurath’s conception of the planner’s role was non-prescriptive and democratic.

... To make rational decisions possible, the planners had to show not only what was doable, but also how it was doable. Thus they were not just tasked to develop one comprehensive economic plan, but several. The people’s representatives were not constrained to accept or reject one more or less fully developed plan, but free to select one from different plans on offer. This highlights what can be called the “empowering” aspect of the enlightenment ambition of Neurath’s conception: it is not just choice that is the matter here, but informed choice, for any such choice was to be made in awareness of what alternatives are foregone.

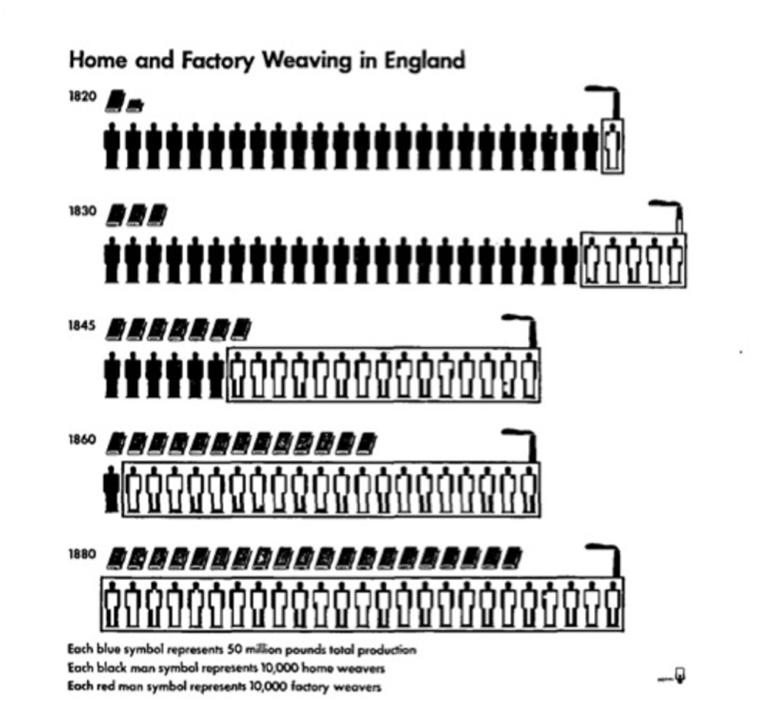

Illustration of home vs factory weavers in Neurath’s ISOTYPE system.

Given all this, why does Schuringa think he can say that Neurath’s socialism fell “short of even the most minimal precepts of socialism?” How is this not socialism on any conception of socialism? Well, Schuringa has “arguments” but they are pretty thin.

Schuringa draws on exactly two criticisms, neither having anything to do with Neurath’s theory, but rather from what went down in 1919, according to the personal history of the Bavarian Republic by the aforementioned anarchist writer and playwright, Erich Mühsam (who was later tortured to death by Nazis). And here, we have to understand that the criticism is not coming directly from Mühsam, but rather from Mühsam as filtered by Schuringa’s scholarship. First, Schuringa says that Mühsam “criticized the indiscriminateness with which Neurath presented his ideas to the bourgeoisie, as well as to the working class.”

One minor problem here. Mühsam, strictly speaking, didn’t say that. He was reporting what some others thought of Neurath. Here is the relevant passage in Mühsam’s account:

[Neurath] presented himself to the RAR (Revolutionary Workers’ Council), was invited by the Munich Workers’ Council to deliver a lecture, and aroused strong interest among the workers, although he was personally met with some suspicion. This suspicion was grounded in the complete indiscriminateness with which Neurath presented his ideas even to the most backward/unenlightened bourgeois circles. [my translation/my emphasis]

Still, you can see why there would be some suspicion. Why was this Austrian professor blabbing to the bourgeoisie about the plans for a socialist state? In this, Neurath simply couldn’t help himself. He was addicted to explaining his ideas about everything to everybody.

Schuringa’s second objection to Neurath is that Mühsam claimed Neurath was “dilettantish.” I think Schuringa wants us to read that in the English language sense of “dilettantish” as saying Neurath was just someone with a casual interest in such matters and that he was ill-informed. That is a crazy charge to throw at Neurath, who was obsessed with the administration of socialist economies and wrote volumes on the topic. He had at that point devoted the better part of his adult life to it. Once again, Schuringa misrepresents what Mühsam was writing. “Dilettantish” is just a bad translation of “dilettantische,” – it’s a false cognate here. In the context of 20th-century German political writing, the expression means something more like “politically naïve.” This certainly makes sense in the context of Mühsam’s writing, if we replace “Dilettantish” with “politically naïve.”

The [political naïvete] of his approach consisted only in this: he believed these measures could be carried out without interfering with the political constitution of the country. He was fond of saying that he would work with any government that allowed him to work undisturbed—whether it was an absolutist-monarchist one or a council republic was all the same to him.

Naïve in hindsight, perhaps, but in the case of Bavaria he was almost successful in this, since he did convince three governments in succession to implement his plans. It worked. Until it didn’t and he got charged with being an accessory to high treason.

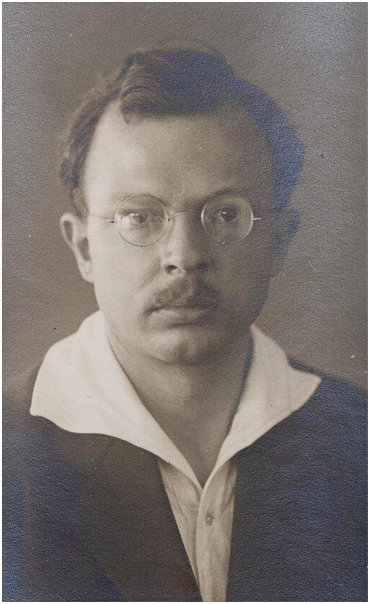

Erich Mühsam and young Otto Neurath

Whether Neurath was naïve or not, it is not correct to infer that Neurath’s views were not radical by socialist standards. As we noted, it was part of his project to eliminate money, not eventually, but right away.

There are other socialists who have advocated the same, including Pyotr Kropotkin, Anton Pannekoek and the council communists, and Anarcho-syndicalist Spain (1936–39), where wages actually were abolished in many collectivized industries and replaced with communal vouchers or direct provision. Neurath’s project was much more radical than what was happening in the Soviet Union at the time, which had adopted a system of money and wages.

My point here is not that Neurath was right, or that he wasn’t politically naïve, but that it is just insane to say that his political radicalism was “falling short of even the most minimal precepts of socialism.” Neurath’s ideas and projects were squarely within the socialist project and were radical, even by today’s standards.

The other important thing to understand was that for Neurath, this kind of socialist, informed-worker economic planning was completely interwoven with the project in logical positivism. In particular, Neurath’s socialism was directly tied to his attacks on metaphysics. For Neurath, metaphysics, like religion, was a great obstacle to economic justice.

It may even run a bit deeper than that. Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm, in his book The Myth of Disenchantment, argues that Neurath felt that by undoing the bourgeois metaphysical structures, the natural life of the proletariat could be restored.

Positivists have often been criticized for being apolitical, but Neurath, at least, put his politics into practice in a way unmatched by any of the major thinkers in the Frankfurt School. Neurath made explicit the political motivations for the revolt against metaphysics in Lebensgestaltung und Klassenkampf (Lifestyle and class struggle, 1928). As a whole, the monograph is largely an attempt to emphasize that “Scientific attitude and solidarity go together.” Neurath’s main argument is that science is a natural complement to the lifestyle of the proletariat; members of the working class are naturally grounded in a commonsense scientific outlook because they are interested in concrete and practical matters like working conditions, safety, access to safe food, and clean drinking water. In a similar fashion, he argued, they are also unencumbered by the intellectual traditions that govern the life of the bourgeois class.

Those “intellectual traditions that govern the life of the bourgeois class” were, as I noted, their abstract metaphysical and formal religious theories. Such theories were corrupt, serving only the bourgeoisie, directing their energies toward projects that benefited no one. Such theories also numbed people to the concerns of individuals while fetishizing abstract concepts such as the German State. In other words, the entire positivist project was not some doctrine that cut people off from their everyday concerns, as Schuringa contends. To the contrary, the entire project was specifically designed to restore concern for the practical everyday needs of people.

On Neurath’s view, class revolution required overthrowing both theology and metaphysics. His campaign against metaphysics was Marxist. In his words, “The cultivation of scientific, unmetaphysical thought, its application above all to social occurrences, is quite Marxist.” The critique of metaphysics, therefore, functioned first and foremost as a critique of ideology. And this brings us back to the epigraph from Neurath at the beginning of this section: “Above all, the fight against metaphysics and theology means the destruction of bourgeois ideology.”

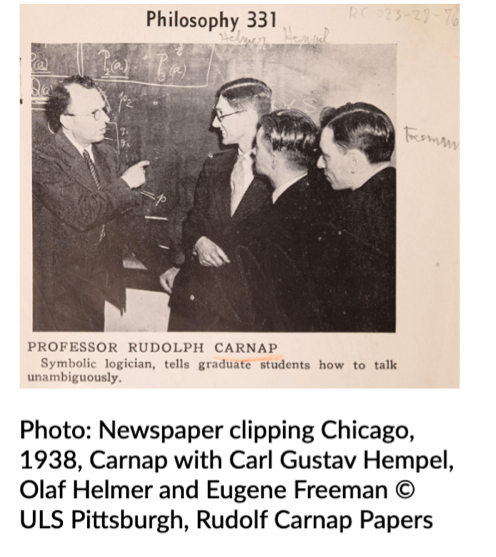

Rudoph Carnap

Schuringa describes Philipp Frank and Rudolf Carnap, as “both of them rather moderate leftists,” and as you can probably guess by now, that is understating the reality of Carnap’s political beliefs. I suppose it all depends on what you mean by a “moderate leftist,” but I don’t know of any understanding of that label on which it would be true of Carnap.

Carnap once remarked to a friend: “If you want to find out what my political views were in the twenties and thirties, read Otto Neurath’s books and articles of that time; his views were also mine.” Well, we just took a tour of Neurath’s politics, and saw that it was a conception of socialism that was bottom-up, relied on an informed proletariat, and deployed a controlled economy that was to function without money. Is that what moderate leftism looks like these days?

Digging into the specifics, we can find that in many respects, Carnap’s were even more radical than Neurath’s in important respects, in that he advocated abandoning the state, and had a vision that would be the stuff of nightmares of right-wingers in the United States – one world government organized by socialist principles.

Carnap’s political identity started to emerge during and immediately after World War I. He opposed the war but served and saw heavy action on the front lines. Already, he was developing an opposition to nationalism and to the very idea of nation-states. His pacifism seems to have intensified after seeing war up close, and that pacifism stayed with him the rest of his life.

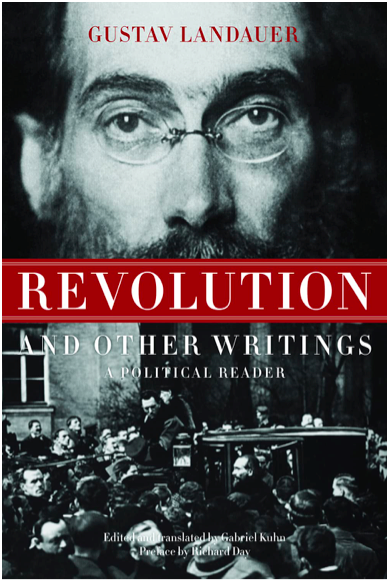

Schuringa notes that Carnap soon became a big fan of the anarchist Gustav Landauer.

Carnap followed [his friend] Bittel in his admiration of the anarchist Gustav Landauer. In Bittel’s words, with which Carnap enthusiastically agreed, Landauer advocated ‘freideutscher socialism: against Marxism, materialism, centralisation, state socialism and for communal cooperative socialism in the spirit of brotherhood’.

That is to say, Landauer was advocating a kind of decentralized, bottom-up socialism that rejected Marx’s materialism and the role of the state.

Landauer was an interesting case. He was a persistent critic of Marxism, but an outlier as an anarchist as well, since he was a passivist. I’m not sure how that went over with Kropotkin.

There is a famous quote from Landauer, which reads that “the state is a social relationship; a certain way of people relating to one another. It can be destroyed by creating new social relationships; i.e., by people relating to one another differently.” People have puzzled over that quote because how could the way we relate to each other dissolve the state and form something new? But I think it does make sense. I suspect it made sense to Carnap as well. And I wonder if that thought wasn’t running in the background as he sought to engineer modes of communicating that had been expunged of metaphysics. Would that naturally lead to new forms of human relations?

In the Introduction to Revolution and Other Writings, Gabriel Kuhn with Siegbert Wolf observe that there has been an attempt to depoliticize Landauer, which is pretty remarkable, and also ironic, given the external attempts to depoliticize Carnap as well.

I suspect that there are two forces at work in this nerfing of political activists – and we will see both at work in this review. First, there are attempts to make intellectual figures seem “safe.” These are the people who play down the politics of people like Landauer and Carnap to make their other work more digestible. On the other hand, there are forces that dismiss the work as not radical enough, and thus not worthy of attention. Schuringa is definitely in the latter camp, as we will see. But it must be said that radical political thought comes in more than one flavor, and it is perhaps a mistake to think that Marx is the most radical option available, or that the iterations of Marx that followed him were actually radical, as opposed to merely derivative, and in some cases psychopathically inhumane.

What Schuringa doesn’t mention is that Landauer had been involved in the Bavarian Soviet Republic with Neurath (you may have noticed that we name-checked Landauer earlier). However, things did not end as well for Landauer as they did for Neurath. When the SPD-controlled German army retook Munich, Landauer was captured. The end, as described by Rudolph Rucker, was grim.

One of [the soldiers] hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim. An eyewitness later said that Landauer used his last strength to shout at his murderers: ‘Finish me off – to be human!’ He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer – one of Germany’s greatest spirits and finest men.”

It seems to me that Carnap carried a number of Landauer’s ideas with him for the rest of his life. Certainly, his pacifist beliefs, his rejection of the state, his socialism, but also Landauer’s idea that if we just relate to each other correctly, the state will, as it were, wither away. We know that Carnap subsequently admired Kautsky and Austrian social democracy and was no Bolshevik. He was certainly no Stalinist. He believed socialism had to be democratic, parliamentarian, and scientific. As I said, it was bottom-up socialism. However, in his diaries, he did entertain a Marxist reading of his paper “Überwindung der Metaphysik” or as we know it, “The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language.” (See Rudolph Carnap Papers, 025–75–10, Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library.)In the 1930s, his immediate concern was the rise of fascism, and he bravely took public stands against it. Thus, in April 1933, Carnap was one of the signatories of the “Declaration of the 93” (“Aufruf der 93” – a petition protesting the dismissal of Jewish and liberal professors and the politicization of academic appointments.

Carnap moved to Prague in 1935, and then to the United States in 1936, where he took a position at the University of Chicago. There is a kind of received view that the surviving members of the Vienna Circle became apolitical when they arrived in the United States. Schuringa certainly perpetuates that narrative, and we will examine it more closely later, but whatever we might say about that narrative, it does not describe Carnap’s political trajectory.

Once in Chicago, Carnap renewed his ties with socialist groups, supported anti-fascist refugeesIn the 1940s through the 1960s, Carnap actually became more political, not less. This is when he further developed his ideas that the nation-state system causes war, and argued that we should abandon the idea of nation-states and move toward peaceful supranational institutions. He was thus an open supporter of the World Federalist Movement and postwar efforts to create stronger global institutions. I’m not saying that these were good ideas; I’m only saying that they were political ideas and that they flew in the face of where America was during the Cold War.

Also going against the flow of the politics of the 1950s, Carnap supported desegregation, liberal immigration, and was openly in opposition to McCarthyism. He signed petitions defending politically targeted academics. He refused a job at UCLA until they lifted their loyalty oath. He became an anti-nuclear activist, signing petitions and joining campaigns for scientific responsibility. He continued to engage in discussions of the role of philosophy in preventing war.

While it was true that Carnap was never public a Marxist, he certainly respected Marx as a social scientist. What he rejected in Marx was not the social goal, but what he regarded as the problematic metaphysics – he rejected dialectical materialism as metaphysical. He also recoiled from the centralizing tendencies that were latent in Marx’s thought (as Bakunin observed). He did support socialist economic planning of the sort Neurath advocated, so long as it was, in some way, bottom-up.

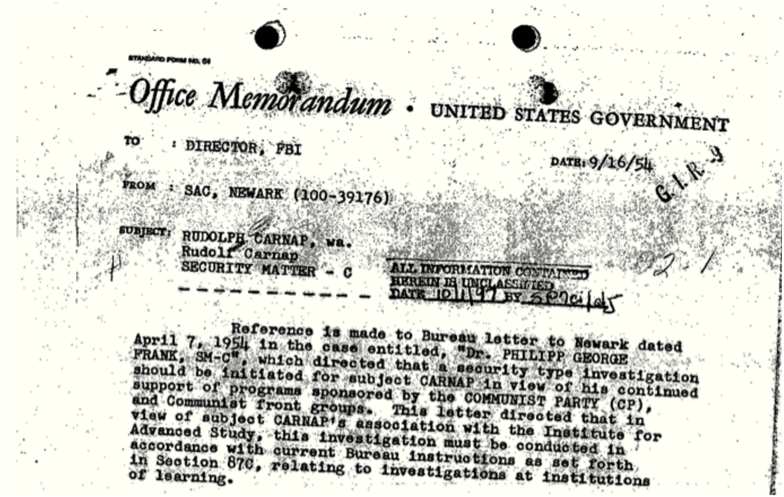

Of course, the best way to understand someone’s politics is by seeing what their political enemies say, and Nazis had a LOT to say about Carnap and, as we saw in the aftermath of Schlick’s death, the Vienna Circle itself.

Paul Krannhals, a Nazi philosopher, Wrote an essay on “German Philosophy and the National Revolution.” In that essay, Krannhals attacked Carnap (by name) as “the theoretician of a rootless scientific worldview (wurzellose Wissenschaftlichkeit) that denies the Volk, history, and destiny.” If that wasn’t enough, he continued to say that “Such men must be excluded from German intellectual life.” (Peter McLaughlin, Carnap and the Legacy of Logical Positivism (Cambridge UP, 2009), p. 39.)

We will look at some further evidence of Carnap’s political activism a bit later (I want to save the best for last), but in the meantime, we need to address a question. Why do people think he was apolitical? In cases like Schuringa’s book, it is pretty obviously a disinformation campaign. But sometimes the depoliticized vision of Carnap is not intentionally hostile. Sometimes it was just people trying to protect him. And sometimes department chairs, deans, and university presidents sanitize the politics of their stars to avoid scrutiny from right-wing politicians. And so too, there is a kind of media filter in which the media sanitizes academics to make them palatable, or perhaps less of a threat to the social order.

The nerfed Carnap they wanted you to see. (probably not from a newspaper, but a U of C publication.)

The bottom line is that Carnap was anti-militarist, socialist-democratic, anti-nationalist, anti-fascist, pro–world government, pro–civil rights, anti-nuclear proliferation. All visibly so. In the Cold War! And Schuringa is calling him a “moderate leftist.”

My point here is that Carnap was not some apolitical logician. In fact, he was never apolitical. As we will see, he did not become apolitical when he moved to the United States, nor when the FBI investigated him, nor when Cold Warriors threatened him. As we will also see, he was deeply political until his last dying day. He was not a “modest liberal.” He was not “bloodless.” He was not, as in Schuringa’s formulation, “removed from the changing scenes of history.” He was not acting as if he was “pursuing … questions from a vantage point situated nowhere in particular, unaffected by social and political reality.” He was not ignorant of or uninterested in “culture, politics, anthropology, psychology, sexuality, religion, literature.” Those are the accusations of his political enemies. And they are false.

Hans Hahn

The third author of the Circle’s manifesto was Hans Hahn. Hahn is best known as a hardcore mathematician – certainly the most mathematical of the Circle members, with the exception of Gödel, who was Hahn’s student. In fact, Gödel’s dissertation was his proof of the incompleteness of arithmetic! But despite being very mathematically inclined, Hahn was also a member of the Left Wing of the Circle, perhaps one of the left-most members.

With respect to mathematics, he was all about pure mathematics – especially analysis and related areas. Some of the main things he’s known for are his work on measure theory and integration (he’s known for the Hahn decomposition theorem), functional analysis (super famous for collaborating with Banach on the Hahn-Banach theorem), and he also did work on ordered groups and series (giving us the Hahn embedding theorem). He also did some work on the foundations/philosophy of mathematics, working on the role of logic in mathematics, the crisis of intuition in mathematics after Cantor, and also wrote about non-constructive proofs. Hahn was politically aligned with (and often described as a leading intellectual of) the SDAPÖ. He was, in that milieu, a key Social Democratic public intellectual. Like other members of the circle, he was involved with teaching in Volkshochschule Wien (Workers’ Adult Education / People’s University), bringing modern mathematics and science to the Social Democratic base. He was also one of the central organizers and leading figures in Verein Ernst Mach (the public-facing part of the Vienna Circle, that included public lectures on philosophical topics – basically the TED talks of that era).

We will return to the issue of worker education a bit later, when Chomsky wonders what exactly happened to that, and asks why the left abandoned such initiatives. It is a good question. But for now, we need to view this effort through the headspace of Hahn and the other members of the Left Wing of the Vienna Circle. This education in mathematics and science was not undertaken as a side hustle, nor as some sort of apolitical project to educate people. Adult education was, at the time, considered to be a kind of pillar of the revolutionary movement. The proletariat needed the tools of science and mathematics, not to cash in, but to be effective in that revolutionary movement.

Before we leave Hahn, however, there is a little known fact about him that sheds light on the true nature of the Vienna Circle, and illustrates that it was not so very far apart from the philosophers of the Frankfurt school, and their quasi-Heideggerian critique that positivism was attempting to “disenchant” the world.

Here I draw an a longish story about one Eleonora Zugum, a 11-year-old Romanian Girl, as reported by in Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm’s The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences.

Eleonora became the center of a series of unusual events. Witnesses reported that they saw objects shudder and levitate in the girl’s presence. Soon, Eleonora developed a bad reputation in the village; as the locals would later tell a visiting researcher, “The grandmother could not die because some evil spirits would not permit her, and thus she had sent for the child, in order, by means of witchcraft, to transfer them to her.” Presently Eleonora herself became convinced that she was suffering from demonic possession.

Eleonora’s father and a group of concerned villagers took her to the house of an old priest. No sooner had they arrived than an iron vessel exploded into pieces. Jugs cracked, heavy objects began to shift around, and the windows suddenly shattered. The priest attempted an exorcism, but the phenomena continued. Fearing Eleonora was still cursed, her family deposited her at the monastery and convent of Gorovei (Mănăstirea Gorovei) in Talpa. Even there, she seemed to be at the mercy of invisible powers that smashed and moved things. The monks became frightened and wanted to expel Eleonora, but were prevented from doing so by the prior of the monastery.

This was no fairy tale, and it was at this point that Eleonora’s story enters the historical record. Kubi Klein, a reporter for the Jewish German-language newspaper Czernowitzer Allgemeine Zeitung, came across Eleonora and published his account of her case on April 18, 1925, under the title “Das verhexte Dorf” (The bewitched village). News about the cursed girl spread through the region. Soon journalists and paranormal investigators were all clamoring to study Eleonora in greater detail. Fearing the impact of this attention, her family committed to her to a mental asylum, where she was kept in isolation.

Fortunately, Eleanora came to the attention of the international parapsychology community, and she was rescued from the asylum and brought to Vienna. There she met the famous mathematician and founding member of the Vienna Circle, Hans Hahn. Hahn was also part of an elite team of paranormal researchers that tested Eleanora’s psychical powers, and he later testified to their authenticity.

What is going on here? It seems that Hahn, like other members of the circle (Carnap, Frank, Feigl, and Hahn’s student, Gödel), was fascinated with things magical and paranormal. Hahn was a founder and member of the executive board of the Austrian Society for Psychical Research (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Psychische Forschung, ASPR). He was a ghostbuster! How do we make sense of this?

Hans Hahn. Mathematician, Logical Positivist, Socialist, and precursor to Peter Venkman?

Were the positivists not the enemies of all things metaphysical? The answer is layered. One take is that they were trying to disenchant these phenomena, but that isn’t so clear. They took these phenomena to be facts that had to be taken seriously, and if we had to adjust science to account for them, well, then science would have to be updated.

Would the positivist really revise the laws of nature to accommodate this type of phenomenon? My friends, even Feigl thought so!

If it were fully established that the phenomena of extrasensory perception, i.e., clairvoyance and telepathy, and perhaps even precognition and psychokinesis, do not result from experimental or statistical errors . . . then our conception of the basic laws of nature may well have to be revised at least in some essential aspects. (Inquiries and Provocations, 314.)

While these sorts of phenomena might find themselves in the “Metaphysics” section of your local bookstore, that isn’t what the positivists meant when they called the target of their critique, “metaphysics.” The positivists were opposed to the metaphysics of the intellectual class – Idealism, organized religion etc. – but there is another notion of metaphysical, the kind you see in bookstores, that has to do with magic and the esoteric. The positivists didn’t necessarily have a problem with that. To the contrary, as Josephson-Storm claims, they saw their project as continuous with that kind of bookstore “metaphysics.” They were the new magicians, and the thought was that they were reconnecting with the natural esoteric beliefs of ordinary folk – rejecting the abstract metaphysical notions that carried intellectual water for the bourgeoisie, German politicians, and the Church. Here is how Josephson-Storm puts it in The Myth of Disenchantment:

For Neurath, instead of science as the culmination of disenchanting Protestant thought, modernity is the return of sorcery. In effect, magic must reappear in order to challenge theology and empty metaphysics. Occult revivals and scientific revolutions would seem to come together. In sum, Neurath was positioning positivism and its unified science as a return, and in that sense as a completion or fulfillment of primitive magic. As he put it elsewhere: “Unified science is the substitute for magic which also once encompassed the whole of life.”

That idea is not just in Neurath. It is in the Circle’s Manifesto itself. Consider this passage from the Manifesto:

The representatives of the scientific world-conception resolutely stand on the ground of simple human experience. They confidently approach the task of removing the metaphysical and theological debris of millennia. Or, as some have it: returning, after a metaphysical interlude, to a unified picture of this world free from theology, which had, in a sense, been the basis of magical beliefs (Zauberglauben) in early times.

(There is a relative pronoun antecedent ambiguity in that translation. It is the “unified picture” that was the basis of magical beliefs, not “theology.”) This lines up with the politics of the members of the Circle, because the idea is that the magical realm (which is continuous with their project) is, as it were, at war with the false Ideologies of the ruling class.

We are going to come back to this, because, in the end, I am going to make the case that the positivists and the Frankfurt School were not so far apart. Collaboration was, and remains, possible.

There are three more members of the Vienna Circle that I want to discuss, because they are going to return at points during our contra-Schuringa story. One member that will play a key role after immigrating to the United States, is Philipp Frank.

Philipp Frank

Philipp Frank was a physicist and a Student of Boltzmann, which is impressive in itself. He was definitely part of the Left Wing of the Circle, but was certainly not as far left as Neurath or Haahn. He was, like many other members of the Circle, a liberal-socialist / Social Democratic sympathizer, closely allied with Hahn and Neurath in the Red Vienna intellectual projects. He was, of course, involved in the Verein Ernst Mach and the Volkshochschule / workers’ education program, teaching modern physics.

Frank is going to play a big picture in our story during the Cold War, when he came under scrutiny from the FBI and when he was trying to raise money for the Unity of Science Project, but there is one important point that I want to make concerning the understanding of the Enlightenment that the members of the Vienna Circle had.

Schuringa, as is clear from his book, is not a big fan of Enlightenment philosophy, and he works hard to situate the members of the Vienna Circle within the Enlightenment project. And for sure, the members of the Circle did view their project as being part of the “Enlightenment,” but they were not using that word in the same way we do today. For example, Neurath considered Marx to be an Enlightenment thinker (see his Empiricism and Sociology, 315). And you can see how that would make sense – it was, at least for Marx, a social-scientific project. It was evidence-based. It worked to overthrow ideologies just as earlier Enlightenment thinkers had. Perhaps all the members of the Circle felt this way about Marx. But there was someone else that they loved too: Nietzsche!

Frank spoke of Nietzsche as a “great Enlightenment thinker,” you can see how they would think of Nietzsche as a continuation of the Enlightenment project, even if, in the end, it seemed destructive of that very project. But Frank notices things in The Will to Power that were aligned with the thinking of the Circle.

Nietzsche’s most significant expression of the positivistic world conception is probably given in the aphorism, called “On the Psychology of Metaphysics,” where he attacks with cutting sharpness the employment of very frequently misused concepts:

This world is apparent: consequently there exists a true world;— this world is conditional: consequently there exists an unconditional world;— this world is full of contradictions: consequently there exists a world that is free from contradictions;— this world is changing: consequently there exists a permanent world;— all false conclusions: (blind faith in the reasoning: if there is A, there must also be its antithetical concept B). [Will to Power, 252.]

It is not to be denied that the philosophy of enlightenment possesses a tragic feature. It destroys the old systems of concepts, but while it is constructing a new system, it is also already laying the foundations for new misuse. For there is no theory without auxiliary concepts, and every such concept is necessarily misused in the course of time. The progress of science takes place in eternal circles. The creative forces must of necessity create perishable buds. They are destroyed in the human consciousness by forces which are themselves marked for destruction. And yet, it is this restless spirit of enlightenment that keeps science from petrifying into a new scholasticism. If physics is to become a church, Mach cries out, I would rather not be called a physicist. And with a paradoxical turn, Nietzsche comes out in defense of the cause of enlightenment against the self-satisfied possessor of an enduring truth.

Apologies for the length of that, but it highlights two important points that we are going to return to throughout this review. The first is the idea that one wants to be suspicious of the sketchy arguments deployed to justify metaphysical concepts. But the second point, and one that speaks to analytic philosophy as well, is the last paragraph in which Frank observes that science (and I would say philosophy) is at its best when there is not a stable set of doctrines – when it is a constant demolition derby of ideas. As we will see, this seems to be a feature of analytic philosophy that Schuringa absolutely cannot abide.

Edgar Zilsel

Edgar Zilsel

It baffles me that Schuringa shows almost no interest in Zilsel – he identifies him as a member of the Circle, relegating him to a few notes regarding his comings and goings and saying nothing about his work. The baffling thing is that Zilsel himself was an important social historian of science. His thesis about the sociology of science – “The Zilsel Thesis” – is laid out in “The Sociological Roots of Modern Science” (1942) and related pieces collected in his book, The Social Origins of Modern Science.

The Zilsel Thesis deserves a mention here because it embodies everything the Vienna Circle was about. The basic idea was that modern science emerged via a fusion of artisans’ empirical skills plus scholars’ theoretical traditions in urban/capitalist social structure. So, to take one of his examples, Galileo’s achievements would not have been possible without the culture of instrument makers, the mechanical knowledge of artisans, and the blending of mathematics with practical craft. Surveyors, navigators, and instrument builders became mediators between scholars and trades. Of interest to the Circle was the idea that modern science is a kind of fusion between practical craft and scholarship. It was not one or the other. The two cannot be separated.

How does someone writing a social history of anything miss Zilsel? In any case, Zilsel was definitely part of the “Left Wing” of the Vienna Circle and was a key component in Red Vienna. He was an Austro-Marxist; he joined the Austrian Social Democratic Party in 1918, wrote for their house journal, Der Kampf, was briefly arrested after the 1934 Austrian civil war, and eventually, forced out of his teaching job. In 1939, he fled Europe for the United States and tried to cobble together some research jobs in California Universities. Destitute and struggling with everything that comes with being an émigré in the United States, he took his life in 1944.

His interest in Austro-Marxism was not purely political; he fused it into his theoretical research. Zilsel explicitly endorsed historical materialism and saw Marxism as a crucial resource for philosophy. His strategy was to blend Marx/Engels with ideas from Boltzmann’s statistical mechanics to argue for empirical laws in history and society that could emerge from lots of random events at the individual level. This is sometimes called the Law of Large Numbers (LLN). Marxists have picked up the LLN as a way to discuss how “necessity” emerges from messy individual events – especially in economics, social statistics, and history. It serves as a kind of bridge between dialectical talk of “tendencies” and the hard math of probability. So Zilsel used LLN-style thinking to naturalize Marxist claims. The key idea is that social laws are no more mysterious than gas laws; both are emergent statistical regularities of huge ensembles.

Happily, Zilsel’s work is making a comeback. In 2017, Jérôme Lamy (historian and sociologist of science at CNRS) and Arnaud Saint-Martin (a member of La France insoumise (LFI)) started a journal on the sociology of science called “Zisel,” in honor of the work of Edgar Zisel.

Some issues of the journal Zilsel

In an article explaining their choice of name for the journal they noted that there may have been some attempt to erase Zisel’s work from the record. It was only rediscovered in the 1980s and is now seen as a precursor to science and technology studies (STS).

Rose Rand

Rose Rand

At least Zilsel got mentioned by Schuringa. Schuringa does not mention Rose (Róża) Rand once, not even in a footnote. I suspect Rand will be remembered as the most revolutionary, and ultimately one of the three most important members of the Vienna Circle (along with Neurath and Carnap). Rose Rand, was born in what is now Lviv, Ukraine and emigrated to Vienna in high school. At the University of Vienna she studied under Schlick, and ended up writing on the Polish logician Tadeusz Kotarbinski, which is already badass. Like the other Circle members, she participated in the adult education programs in Red Vienna, but also worked as a researcher in a Psychiatric Hospital. In Vienna. In the age of Freud. Think about that.

A theme that I will return to in this review/essay is the role of the scribes of the revolutionary movement. If we think of the project of the Vienna Circle as being revolutionary, and it is hard not to see it as revolutionary in the aftermath of Schlick’s murder, then Rose Rand was the scribe of this revolution. She took detailed minutes of Circle meetings for a period of about three years. Most famously, she took notes during the meeting in which Gödel presented his results about the incompleteness of arithmetic to the Circle. She also preserved an enormous amount of correspondence with members of the Circle and other contemporaries, leaving behind a huge archive of documents – over 1600 of her letters are now kept at the University of Pittsburgh library, along with a treasure trove of unpublished manuscripts and notes in Russian, Polish, German, and English, and her own shorthand. People are just now beginning to sift through what is an intellectual goldmine. (You can see part of her archive here.)

Online records are inconsistent, but in either 1938 or 1939, Rand (who was Jewish) escaped continental Europe with the help of the British philosopher Susan Stebbing (we will discuss Stebbing next). Once in England, however, finding academic work was not easy. Thanks to Stebbing, Rand had some financial support at Cambridge (allowing her to interact with Wittgenstein), but she lost that support in 1943 and had to work as a nurse and as a worker at a metal fabrication factory while also teaching night classes on German and psychology at area technical colleges. In 1954, she moved to the United States, and did not fare much better, cobbling together occasional adjunct teaching positions and jobs translating papers by Polish logicians. Her financial position was precarious until the very end.

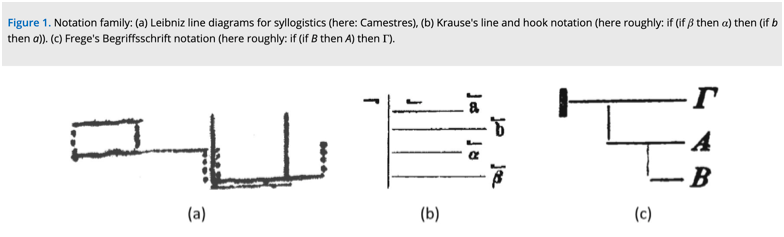

When I say that I think she was the most revolutionary of the members of the Vienna Circle, what I mean is that she was able to meld their two projects in a way that the others had not, perhaps with the exception of Zilsel. My thought is that running through the history of the Vienna Circle, there were two distinct projects – one having to do with social engagement and the other having to do with logic and mathematics. Those projects were unified in that the scientific project could free us from metaphysics, which in turn could free us from right-wing bourgeois ideology. Zilsel more directly unified these projects by applying formal ideas from statistical mechanics to sociology. Rand also pursued a more direct integration; she pursued the idea of extending formal logic from a logic that could describe or represent states of affairs (the task that it served in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, for example), to a logic for demand, serving as a precursor to what is now called deontic logic (a logic of obligation).

In 1939, more than a decade before deontic logic emerged within 20th-century formal logic (usually credited to von Wright), Rand published a paper titled “Logik der Forderungssätze” in a journal on legal theory called Revue Internationale de la Théorie du Droit, 1(1), 308–322. Basically, she was extending the domain of formal logic to include demands (for example, legal demands), and she talked about the logic that they obeyed – what could be contradictory demands, what could be the negation of a demand (not the absence of a demand but a demand to not do something), how demands can be iterated, etc. The paper was revolutionary in two ways. First, it was an early attempt to develop a logic for non-representational phenomena. Second, it is the idea that logic is not static, and it can be extended to the domains of the practical and legal. One way to put it is that it was a logic deeply aligned with the Vienna Circle’s manifesto.

Rand’s paper was republished in English in Synthese in 1962, so it was on someone’s radar, but I do not believe people fully understood how revolutionary Rand’s work was. Or perhaps some of them did; the same year her paper appeared in German (1939), the Yale logician Fredric Fitch reviewed her paper in the Journal of Symbolic Logic. Two years later, Fitch acquired a new student, named Ruth Barcan. Logicians have precursors, too.It is somewhat criminal that universities in England and the United States would not hire Rand when she left Vienna. The reasons they didn’t are pretty obvious: a single Jewish woman who was reportedly “socially awkward” would have had a tough go getting hired in the 1940s, and it might also be the case that her ideas were just too radical as well. You have to imagine what the ethicists would have thought of her work, extending logic to the holy realm of the ethical. Or imagine what the logicians would have thought of her gumming up their sacred Aristotelian logic, or their propositional logic, with talk about obligations and demands.

Even in the 1980s, when I was a graduate student at Columbia, I remember Ruth Marcus delivering a talk on deontological logic. I was thinking, some 40 years after Rand had published her pioneering work, what the hell was that? It was still bleeding-edge stuff 40 years later. So, like I said, it is criminal that Rand was not hired by an anglophone university, and that was a clear injustice for her, but it also makes me wonder about the responsibility of universities to their students. Each and every university in England and the United States had the opportunity to hire a person who was not merely doing cutting-edge work, but who had sat there at the table with the Vienna Circle, taking copious notes on work that laid the foundations for 20th-century philosophy, logic, mathematics, and science. She could have told the students about meeting Einstein, or what it was like being a researcher in a Viennese psychiatric hospital in the age of Freud, or what it was like to be in Vienna during the rise of fascism and the murder of Schlick, or what it was like to flee from Nazis, or to take a class from Wittgenstein, or what it was like to be sitting at the table, taking notes, the day that Gödel informed the world that arithmetic was fucking incomplete.

Not one university cared enough about their students to hire her and thereby give them first-person access to the deep intellectual history of the 20th Century. Like I said: fucking criminal.

Oh and also: too bad Schuringa didn’t have space to mention her once in his 336 page work on the history of analytic philosophy.When Schuringa turns his gaze to England and the early days of British analytic philosophy, he persists in his strategy of downplaying the political activism and social engagement of analytic philosophers. And we can begin with is treatment of Susan Stebbing, the woman who helped Rose Rand emigrate to England.

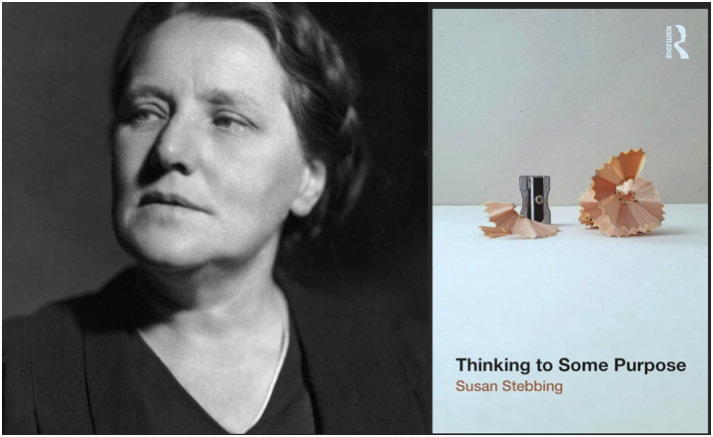

Susan Stebbing

Susan Stebbing and Thinking to Some Purpose. Still in print.

Susan Stebbing was one of the giants of 20th-century analytic philosophy and was the very first woman in Great Britain to receive a chair in philosophy (at Bedford College in London). Her work was very much in the Moorean tradition, but applied to the state of the world. That is, while G.E. Moore called for clarity and common sense about whether he had a hand, Stebbing was calling for clarity and common sense as a foil against totalitarianism around the world. Like the members of the Vienna Circle, she was proposing exact thinking as an antidote for demented times.

Schuringa’s potted biography informs us that Stebbing was “Born in a middle-class home, and privately educated at James Allen’s Girls’ School in Dulwich,” but neglects to tell us that she was orphaned at age 16, suffered from some unspecified childhood disease, and also suffered her entire life from Ménière’s disease – a condition that could lay her up for days with severe vertigo. She acquired cancer around 1941, and subsequently died of it in 1946, at age 56.

Stebbing was perhaps more closely aligned with the Vienna Circle than anyone else in England, even more than Wittgenstein, oddly enough. And I would say certainly more so than AJ Ayer, in that her understanding of the project was closer to what was going on in Vienna. (Ayer is one of the people who suppressed the political aspect of their project, thus giving ammunition to detractors like Schuringa). Stebbing, unlike Ayer, seemed to understand and internalize the Vienna Circle project – in particular, the idea that the point of scientific philosophy and rejecting metaphysics was to better the human condition. Before receiving her Chair in England, she was a visiting professor for two years at Columbia University in New York, and one of her students, named P. Magg, had this to say about her project

Logic had been to us a field in which we were supposed to be objective, rational, neutral, scientific and even aloof from the affairs of the world .... But here we found a different kind of logician ... who made it clear that reason and logic, mind and science, had important services to perform in the very problems of the relation of society to man, of man to society.