Exclusive 3:16 Interview With Jeremy Bentham

According to Crimmins, James E., "Jeremy Bentham", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2024 Edition)' Jeremy Bentham, jurist and political reformer, is the philosopher whose name is most closely associated with the foundational era of the modern utilitarian tradition. Earlier moralists had enunciated several of the core ideas and characteristic terminology of utilitarian philosophy, most notably John Gay, Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, Claude-Adrien Helvétius and Cesare Beccaria, but it was Bentham who rendered the theory in its recognisably secular and systematic form and made it a critical tool of moral and legal philosophy and political and social improvement. In 1776, he first announced himself to the world as a proponent of utility as the guiding principle of conduct and law in A Fragment on Government. In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (printed 1780, published 1789), as a preliminary to developing a theory of penal law he detailed the basic elements of classical utilitarian theory. The penal code was to be the first in a collection of codes that would constitute the utilitarian pannomion, a complete body of law based on the utility principle, the development of which was to engage Bentham in a lifetime’s work and was to include civil, procedural, and constitutional law. As a by-product, and in the interstices between the sub-codes of this vast legislative edifice, Bentham’s writings ranged across ethics, ontology, logic, political economy, judicial administration, poor law reform, prison reform, punishment, policing, international law, education, religious beliefs and institutions, democratic theory, government, and administration. In all these areas he made major contributions that continue to feature in discussions of utilitarianism, notably its moral, legal, economic and political forms. Upon this rests Bentham’s reputation as one of the great thinkers in modern philosophy.'

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Jeremy Bentham: I’ll tell you a story from my schooldays. One day, as the Duchess of Leeds was traversing the playground where I was amusing myself with other boys— one little boy amongst many great ones — the duchess called me to her, and said — ‘ Little Bentham, you know who I am." I had no notion she was a great lady, and answered — “ No, madam, no! I have not that honour."

I found that some strange tale had been told of my precocity, and my answer was thought very felicitous; and, not long afterwards, I was invited to go home with her sons to the duke's. I was full of ambition; accustomed to hear myself puffed and praised; and my father was always dinning into my ears the necessity of pushing myself forward — so be hailed this visit as the making of my fortune.

A short time before dinner, I was summoned up stairs to the duke's apartment, where was a physician, to whom he said: ‘This is Bentham— a little philosopher.' ‘A philosopher!' said the doctor; ' Can yon screw your head off and on.’ ‘No, sir’ I said. ‘Oh, then, you are no philosopher.’

3:16: You see philosophy as part of a way of making a practical difference?

JB: My way is - in the order of tractation I mean which in many respects is a very different thing from the order of investigation - first to consider what is possible, next what is eligible and lastly what is established. Montesquieu, Barrington, Beccaria, and Helvetius, but most of all Helvetius, set me on the principle.

3:16: Do you think you suceeded?

JB: Well Richard, what Locke did, was to destroy the notion of innate ideas. What Newton did, was to throw light on one branch of science. But I have planted the tree of Utility— I have planted it deep, and spread it wide. I took the virtues as referred to by Aristotle, traced such of them as would blend with mine, and let the rest evaporate.

3:16: You dislike philosophy that works on just language rather than practical matters don’t you?

JB: I say this Richard: Inspire a contempt for ancient philosophy, or philosophy of words.

3:16: You coined the phrase Utilitarianism. When did you first start developing this idea?

JB: At an age a few months before or after seven years, the first embers of it were kindled by Telemachus, By an early pamphlet of Priestley the date of which has fled from my recollection, light was added to the warmth. In the phrase, ‘ the greatest happiness of the greatest number,' I then saw delineated, for the first time, a plain as well as a true standard for whatever is right or wrong, useful, useless, or mischievous in human conduct, whether in the field of morals or of politics. It was, I think, in my, twenty-second year, that I saw in it the, foundation of what seemed to me the only correct and instructive encyclopaedic arrangement — a map or chart of the field of thought and action: it is the same map which stands in the work entitled ‘Chrestomathia’. I felt the sensation of Archimedes when I committed the first rough and imperfect outline to one side of a half-sheet of paper; which, not entirely useless, served, I hope, to help to kindle a more substantial flame.

Utility was an unfortunately chosen word. The idea it gives is a vague one. Dumont insists on retaining the word. He is bigoted, old, and indisposed to adopt what is new, even though it should be better.

3:16: As you suggested a moment ago, you admire Locke ?

JB: Locke ! He’s first master of intellectual truth without whom those who have taught me would have been as nothing!

3:16: Wow. So you see this principle of utility as the key to all politics and ethics?

JB: All inconsistencies, all surprises, have vanished: everything that has served to make the field of politics a labyrinth, has vanished. A clue to the interior of the labyrinth has been found : it is the principle of self-preference. Man, from the very constitution of his nature, prefers his own happiness to that of all other sensitive beings put together : but for this self preference, the species could not have had existence. Place the chief care of each man in any other breast or breasts than his own, the case of infancy and other cases of intrinsic helplessness excepted, a few years, not to say a few months or weeks, would suffice to sweep the whole species from the earth.

3:16: And from this position you realised that neither a disinterested moral principle such as proposed by Kant nor tender feelings towards others as proposed by sentimentalists like Hutcheson, Hume, and Smith were the basis of human ethics?

JB: By this position, neither the tenderest Sympathy, nor anything that commonly goes by the name of disinterestedness, improper and deceptive as the appellation is, is denied. Peregrinsus Proteus the man whom Lucian saw burning himself alive, though not altogether without reluctance, in the eyes of an admiring multitude, and without any anticipation of a hereafter, was no exception to it. It was interest, self-regarding interest, that set fire to this so extraordinary a funeral pile. Yes; and interest there is in every human breast for every motive for every desire, for every pain and pleasure. Be it ever so feeble, no pain or pleasure but, under favourable circumstances, as Aaron's serpent swallowed up all other serpents, is capable of swallowing up all other pains and pleasures, — the interest belonging to all other interests: no pain, no pleasure so weak, but, under favourable circumstances, may have magnitude enough in the mind to eclipse dl other pains, as well as all other pleasures; strength enough to close the eyelids of the mind against all other pains, as well as all other pleasures.

3:16: So what is utility?

JB: By utility is meant that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness (all this in the present case come to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered: if that party be the community in general, then the happiness of the community; if a particular individual, then the happiness of that individual.

3:16: So this is what drives your philosophical outlook?

JB: Yes. Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it. In words a man may pretend to abjure their empire: but in reality he will remain subject to it all the while. The principle of utility recognises this subjection, and assumes it for the foundation of that system, the object of which is to rear the fabric of felicity by the hands of reason and of law. Systems which attempt to question it, deal in sounds instead of sense, in caprice instead of reason, in darkness instead of light.

3:16: And you think that Utilitarianism will benefit the whole community don't you? What is a community in this sense?

JB: The sum of the interests of the several members who compose it. It is in vain to talk of the interest of the community, without understanding what is the interest of the individual. A thing is said to promote the interest of an individual, when it tends to add to the sum total of his pleasures: or, what comes to the same thing, to diminish the sum total of his pains.

3:16: So is the interest of the community just is the sum of the interests of the individuals in it?

JB: Richard, the interest of the community is one of the most general expressions that can occur in the phraseology of morals: no wonder that the meaning of it is often lost. When it has a meaning, it is this. The community is a fictitious body, composed of the individual persons who are considered as constituting as it were its members. The interest of the community then is, what is it?-the sum of the interests of the several members who compose it.

3:16: You do think however that by taking care of others pleasures we also add to our own don’t you?

JB: Create all the happiness you are able to create: remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you to add something to the pleasure of others, or to diminish something of their pains. And for every grain of enjoyment you sow in the bosom of another, you shall find a harvest in your own bosom; while every sorrow which you pluck out from the thoughts and feelings of a fellow creature shall be replaced by beautiful peace and joy in the sanctuary of your soul. A good system of morals, would give the practiser of them the pleasures of sympathy and the benefits of friendship. It would teach him to refrain from annoying others.

3:16: How many of the surviving and blended Aristotelian virtues you mentioned earlier remain in your system?

JB: The classification of the virtues resolves itself into four : pure self-regarding prudence, extra-regarding prudence, negative-effective benevolence, positive effective benevolence, or the benevolence accompanied with or followed by beneficence. For a man to take care of himself, is prudence— of others, is benevolence ; and these two heads exhaust the subject. There is benevolence on a small scale, and benevolence on a large scale. In treating the subject, take the simple cases first, the complicated afterwards. The pleasure of effective benevolence, on the widest scale, few are susceptible of- it is a choice and aristocratical pleasure. You must show, how, by consulting the interests and happiness of other persons, pain may be avoided — pleasure created.

The great difficulty is the mistaking the adjacent for the permanent interest. An atomic speck upon the eye, will cover an island. The mistake may be seen in a thousand instances. A man cohabits with a woman. He obeys the impulse of interest, and gets diseased. Esau gets a mess of pottage. He obeys the impulse of interest, and loses his birthright.

3:16: You think we should always be kind don't you?

JB: On how many occasions do we give pain, when we might give pleasure ? Every act of kindness is, in fact, an exercise of power, and a stock of friendship laid up ; and why should not power exercise itself as well in the production of pleasure as of pain ? If you do not draw down friendship, you alienate enmity.

3:16: Is there a distinction to be made between pleasure and happiness?

JB: The distinction between pleasure and happiness, is, that happiness is not susceptible of division, but pleasure is. A pleasure is single, happiness is a blended result, like wealth. Now, nobody would call a rag wealth, and yet It is a part of the matter of wealth.

3:16: You talk about sinister interests. What do you mean by that?

JB: Sinister interests, two in the same breast- lawyer’s interest and ruling statesman’s interest: lawyer’s interest, hostile to that of all suitors, and of all those who may have need to be so, that is to say-of all who are not lawyers. Ruling statesman’s interest, hostile to all subjects’ interest, in a form of government, which, to the inclination common to all breasts, adds in the ruling hands adequate power: power, to an amount sufficient for winding up to the pitch of perfection the system of depredation and oppression: power, by means of the corruption and delusion, which are the essence of this form of government, in addition to that physical force and those means of intimidation and remuneration, which belong of necessity to every form of government.

3:16: Is utility what drives governance and equally well explains why reforms are needed?

JB: If self-preference has place in every human breast, then, if rulers are men, so must it have in every ruling breast. Government has, accordingly, under every form comprehending laws and institutions, had for its object the greatest happiness, not of those over whom, but of those by whom, it has been exercised; the interest not of the many, but of the few, or even of the one, has been the prevalent interest; and to that interest all others have been, at all times, sacrificed. To these few, or this one, depredation has everywhere been the grand object, oppression a subsidiary one: where, to the purpose of depredation, oppression has sufficed; oppression, as being the cheaper instrument, has been employed alone: where the aid of corruption has been necessary, the aid of it, notwithstanding the expense of it, has been called in ; and what has been lost in quantity has thus been gained in stability.

3:16: And by ‘this one’ I guess you mean the monarch?

JB: Yes.

3:16: So what do you mean by reform?

JB: By reform is meant, or at least in it is included, abolition of corruptive influence. All those who see, in the matter and fruit of corruptive influence, the object of their desires, are, therefore, whether in possession or expectancy, alike enemies to reform in every shape. Improvement, in so far as applied to political power, to the quantity of it, or the distribution of it, is but another word for reform ; is but reform under another name : they are, therefore, alike enemies to improvement — to improvement in every such shape. But when, in any shape, improvement is brought to view and advocated, it is naturally advocated upon right and proper principles. The all-comprehensive and all-directing principle, the greatest-happiness principle, is, in some shape or other, in some point of view or other, brought forward.

3:16: Do you think people support this principle?

JB: The opinion of the world – I am speaking of the people in this country - is commonly in favour of the principle of utility : it sometimes is against it. According to most of its judgments, that principle should be just : according to some of them, it should be false.

3:16: And you think basically all genuine alternative standards turn out to be the same standard?

JB: I do. Other standards are occasionally set up, which, when examined, appear to be either the same- standard under a disguise, or no standard at all, but a man's own opinion under a disguise new dressed out, and brought into court to give testimony for itself.

3:16: Really?

JB: What is it that a man means when he asks for a reason why he should do a thing ? Some consideration from which it may appear that the doing it will make for his happiness. What is it that a statesman means when he asks for a reason why such a thing should be done? Some consideration whereby it may appear that it’s being done will make for the happiness of the state.

3:16: So how do you explain this universality? What’s the source?

JB: Maxims of utility are propositions deduced from the testimony of sense. Now, it is as much safer as it is shorter, to trust to one's senses, than to one's interpretation of a book, filled with obscurity and apparent contradictions.

3:16: Ok. So how do you propose we measure utility?

JB: To take an exact account of the general tendency of any act, by which the interests of a community are affected, would require that a person should be able to take an account of the number of persons whose interests appear to be concerned; of the value of each interest; of the tendency of the act, and of the degree of that tendency, with respect to each interest; and of the sum of all those interests, as affected by the act in question. For this purpose, the value of a pleasure or pain, considered by itself, will be greater or less, according to the four following circumstances: Its intensity. Its duration. Its certainty or uncertainty. Its propinquity or remoteness.

3:16: And is this the way its calculated in the community?

JB: These are to be considered with respect to each person concerned; and if the act is to be estimated by its tendency to produce pleasure or pain in the community, then the number of persons affected (extent) must also be taken into account. To these are to be added two other circumstances: Its fecundity, or the chance it has of being followed by sensations of the same kind: that is, pleasures, if it be a pleasure: pains, if it be a pain. Its purity, or the chance it has of not being followed by sensations of the opposite kind: that is, pains, if it be a pleasure: pleasures, if it be a pain.

3:16 And how does the calculus work?

JB: Sum up all the values of all the pleasures on the one side, and those of all the pains on the other: the balance, if it be on the side of pleasure, will give the good tendency of the act upon the whole; if on the side of pain, the bad tendency of it upon the whole.

3:16: Is all this a government’s business?

JB: Yes it is Richard. The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation

3:16: So laws should be based on maximising happiness?

JB: Of course. The end of every human law is the greatest happiness of the greatest number: in this is comprised the whole duty of man considered as a member of political society. The laws ought to be so disposed as to make the interest of every individual coincide with the interests of the whole.

3:16: And yet you also think law must include inflicting punishments and therefore pain?

JB: If law did not concern pains and pleasures, it would be a very idle business—a business in no way superior in dignity, and much inferior in amusement to dominoes or push-pin. It does, however, concern pain and pleasure. Pain and pleasure await each motion of its will. This, however, lawyers are wonderfully disposed to forget: it never seems to have entered into the heads of some, and it is this inattention that is the source of all their absurdities. Hence their quaint reasoning and ridiculous conundrums.

3:16: You see some law as fiction? What do you mean by this?

JB: In English law, a fiction is a syphilis, which runs in every vein, and carries into every part of the system, the principle of rottenness. In the mind of all, fiction, in the logical sense, has been the coin of necessity; - in that of poets of amusement-in that of the priest of imposture-in that of the lawyer of fraud and extortion.

3:16: So how exactly are law and punishment connected in utilitarianism?

JB: All punishment is mischief: all punishment in itself is evil. Upon the principle of utility, if it ought at all to be admitted, it ought to be admitted in as far as it promises to exclude some greater evil. If it ought at all to be inflicted, it ought to be inflicted in the least quantity that can answer the purpose: as far as it promises to exclude some greater evil, it is eligible; as far as it does not promise to exclude some greater evil, it is not eligible.

In every case, therefore, punishment ought to be as much as possible subtracted. It ought not to be forgotten, although it has been frequently forgotten, that the delinquent is a member of the community, as well as any other individual-as well as the party injured himself; and that there is just as much reason for consulting his interest as that of any other. His welfare is proportionally the welfare of the community-his suffering the suffering of the community. It may be right that the interest of the delinquent should in part be sacrificed to that of the rest of the community; but it never can be right that it should be totally disregarded.

3:16: And should laws always be clear?

JB: To the generality of the people, the law ought to be known: to be known, it must be in a state fit for being made known: to be fit for being made known, it must be as short as possible, consistent with clearness; it must be as plain and simple as possible, consistent with correctness: otherwise, though it be known, it will not be understood.

3:16: What do you say to those who deny the principle of utility?

JB: When a man attempts to combat the principle of utility, it is with reasons drawn, without his being aware of it, from that very principle itself.

3:16: Now you’ve also written a lot about sovereignty. How does this notion connect with utility?

JB: Well Richard, The sovereign, in the case here in question, is either a single person, or an aggregate body: if a single person, he is styled a monarch; if an aggregate body, he is styled an assembly. In either case, the sovereign is that person or body, the expression of whose will, whether by word or by deed, is the expression of the will of the state; and to whose will the whole political society is (no matter by what means) supposed to be in a disposition to pay obedience. The end of conduct, which a sovereign ought to observe relative to his own subjects ought to be the greatest happiness of the society concerned. This statement clarifies that the sovereign’s legislative acts are justified and evaluated by their utility- their capacity to maximize the happiness of the governed community.

3:16: Why are Locke and Helvetius so important when we consider laws?

JB: A Digest of the Laws is a work that could not have been executed with advantage before Locke and Helvetius had written: the first establishing a test of perspicuity for ideas; the latter establishing a standard of rectitude for actions. The idea annexed to a word is a perspicuous one, when the simple ideas included under it are assignable. This is what we owe to Locke. A sort of action is a right one, when the tendency of it is to augment the mass of happiness in the community. This is what we are indebted for to Helvetius.

The matter of the Law is to be governed by Helvetius. For the form and expression of it we must resort to Locke. From Locke it must receive the ruling principles of its form — from Helvetius of its matter. By the principles laid down by Locke it must be governed, inasmuch as it is a discourse ; by those of Helvetius, inasmuch as it is a discourse from authority, predicting punishment for some modes of conduct, and reward for others.

3:16: And you think we should educate people for happiness for all and suppress any education teaching the ways and means of being happy at the expense of others?

JB: The common end of every persons education is Happiness. The only active plan of education the state ought to encourage, is that which tends no otherwise to increase the happiness of the individual than by increasing, at the same time, the happiness of the community. This is done by improving the arts and sciences which produce the instruments of happiness, or directing them in their application. This, too, is the only plan of active education the preceptor ought to promote mote by his instructions. The arts of supplanting and competition - where the advancement of one man is we depression of another- ought to be noticed in no other view than that of pointing out the means of frustrating them : they are of that sort of pernicious or unprofitable secrets, which it is right to teach only to make them inefficacious.

3:16: Might that mean the person of talent won’t be recognised?

JB: Has a man talents? He owes them to his country in every way in which they can be serviceable.

3:16: Do we need laws because even if everything was ideally utilitarian there would be disputes?

JB: Yes.

3:16: Even though laws take away some freedom?

JB: You're right Richard, every law is an evil, for every law is an infraction of liberty: And I repeat that government has but a choice of evils: In making this choice, what ought to be the object of the legislator? He ought to assure himself of two things; 1st, that in every case, the incidents which he tries to prevent are really evils; and 2ndly, that if evils, they are greater than those which he employs to prevent them. There are then two things to be regarded; the evil of the offence and the evil of the law; the evil of the malady and the evil of the remedy. An evil comes rarely alone. A lot of evil cannot well fall upon an individual without spreading itself about him, as about a common centre. In the course of its progress we see it take different shapes: we see evil of one kind issue from evil of another kind; evil proceed from good and good from evil. All these changes, it is important to know and to distinguish; in this, in fact, consists the essence of legislation.

3:16: Why do you oppose monarchy?

JB: Greedy of incense without caring to deserve it : fond of any principle of awe that could serve to screen his person against attack — regardless whether it rooted there, glad to behold it planted by however ignoble hands ; content to draw upon his office for a perpetual tribute of respect, without ever thinking of deserving it. Such is the condition of a king! Of corruption, the principal and direct use is, to engage the representatives of the people to betray their trust, and sell themselves and the people to the universal corrupter-the monarch, in his capacity of corrupter-general.

I met Burke once . He gave me great disgust. It was just at the dawn of the French Revolution. I imagined everybody would acknowledge it was desirable that a bridle should be put on despotic power. All that Burke retorted was in a word — "Faction:' and he was very angry at the idea of any bridle being put upon the king.

3:16: Bolivar and Napoleon also found your utilitarianism problematic didn't they?

JB: Bolivar's despotism cannot tolerate the greatest-happiness principle. He must put the judge out of the way before whose tribunal he trembles — and, unhappily, he has powerto do so. Buonaparte was in the same state of mind. Talleyrand put into his hand, one afternoon, the Traites de Legislation: next morning it was returned to him, and Buonaparte said, 'Tis a work of genius but never, as far as I know, did he mention it again: indeed it could not answer his purposes.I had once a good opinion of Napoleon: and as a French citizen I voted for his being Consul for life. I do not distinctly remember the grounds which induced me to do this : I thought it was the least evil. Buonaparte's Code was only for despots. Talleyrand said my law projects were works of genius, but not adapted for purposes of tyranny.

3:16: So are you a democrat?

JB: I’ll put it this way Richard: The only choice which Providence has graciously left to a vicious government is either to fall by the people if they become enlightened, or with them, if they are kept enslaved and ignorant. No man is good enough to govern another man without that other man's consent. In the arithmetic of political interests, representative democracy is the only system that limits the sinister interests of those in positions of power while promoting the interests of those without power. Hence, I advocate the elimination of royal patronage, a substantial extension of the franchise, annual elections by secret ballot, the election of intellectually qualified and independent members of parliament with a system of fines to ensure regular attendance, and the accurate and regular publication of parliamentary debates. Without these reforms, Britain risks revolution.

3:16: And you think the principle of utility extends to animals don’t you?

JB: What other agents then are there, which, at the same time that they are under the influence of man's direction, are susceptible of happiness? They are of two sorts: Other human beings who are styled persons. Other animals, which, on account of their interests having been neglected by the insensibility of the ancient jurists, stand degraded into the class of things... But is there any reason why we should be suffered to torment them? Not any that I can see. Are there any why we should not be suffered to torment them? Yes, several. I became once very intimate with a colony of mice. They used to run up my legs, and eat crumbs from my lap. I love everything that has four legs.

3:16: And public opinion is very important to you isn’t it?

JB: Under a government of Laws, what is the motto of a good citizen? To obey punctually; to censure freely. By the publication system, understand that by which the several matters of fact, acquaintance wherewith is in any wise material to the business of the various departments of government, are rendered, or endeavoured to be rendered, public.

3:16: A constitution is an important part of all this isn’t it?

JB: When I say the greatest happiness of the whole community ought to be the end or object of pursuit, in every branch of the law-of the political rule of action, and of the constitutional branch in particular, what is it that I express?-this and no more, namely that it is my wish, my desire, that the greatest happiness of the whole community may be the object of pursuit in every branch of the law, and in the constitutional branch in particular.

3:16: Are you in favour of the separation of powers, the kind of thing Montesquieu writes about and authoritarian governments tend to dislike?

JB: Well Richard, the principle of the separation of powers, as commonly understood, is ambiguous. In some forms, I accept it; in others, I reject it. The mere division of functions, without reference to utility or the happiness of the people, is insufficient as a safeguard. Montesquieu’s discussion of the separation of powers is destitute of all reference to the ends of government, or to the means by which those ends are to be attained.

3:16: So we need to reference ends of government in order to make sense of the separation?

JB: Yes, and the only object of government ought to be the greatest possible happiness of the community.

3:16: You don’t rate Montesquieu do you?

JB: Locke-— dry, cold, languid, wearisome, will live for ever. Montesquieu — rapid, brilliant, glorious, enchanting, will not outlive his century. I could make an immense book upon the defects of Montesquieu — I could make not a small one upon his excellencies. It might be worth while to make both, if Montesquieu could live.

3:16: You write a lot about the Political economy. Is this element of politics about making things secure enough to do good business? Is this what you mean by the rule of behalf-be-quiet?

JB: Yes. Whatever measures cannot be justified as exceptions to that rule, may be considered as non agenda on the part of government. The art, therefore, is reduced within a small compass: security and freedom are all that industry requires. The request which agriculture, manufactures, and commerce present to governments, is modest and reasonable as that which Diogenes made to Alexander: ‘Stand out of my sunshine.’ We have no need of favour-we require only a secure and open path.

3:16: Adam Smith’s one of the great political economy philosophers and you admire much of what he says – you both attack colonialism for example - but you clashed with him over the issue of usury didn’t you. Why ?

JB: Richard, let’s be frank here. Adam Smith, the father of political economy, a writer of consummate genius, whose extensive knowledge and profound reflections have thrown more light upon the science of legislation than all the writers who have gone before him, has, however, in the case of usury, given his sanction to a doctrine which, if acted upon, would have the effect of cramping the energies of industry, and restraining the spirit of enterprise, by imposing arbitrary restrictions upon the terms on which money may be borrowed.

3:16: You also call him out on his sentimentalist approach to ethics don’t you?

JB: Smith’s system, built upon the foundation of sympathy and the impartial spectator, is in truth a system of sentiment, not of reason. It is utility alone that can furnish a clear and consistent principle for legislation and morals. All systems that rely on sympathy and antipathy are liable to endless confusion and contradiction; it is only by reference to utility that we can hope to escape these difficulties and arrive at sound conclusions.

3:16: What about the idea that some laws and morals are handed down to us from nature?

JB: It’s rubbish Richard, simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights - rhetorical nonsense, - nonsense upon stilts, a perversion of language.. Rights are the fruits of the law, and of the law alone. There are no rights without law-no rights contrary to the law-no rights anterior to the law. Before the existence of laws there may be reasons for wishing that there were laws-and doubtless such reasons cannot be wanting, and those of the strongest kind;-but a reason for wishing that we possessed a right, does not constitute a right. To confound the existence of a reason for wishing that we possessed a right, with the existence of the right itself, is to confound the existence of a want with the means of relieving it. It is the same as if one should say, everybody is subject to hunger, therefore everybody has something to eat.

3:16: Some people think there are hierarchies of pleasures – so my low down pleasures aren’t to count as much as someone’s high culture ones? Are they right?

JB: No Richard, all pleasures are equal. The pleasure gained from poetry is just as valuable as that gained from playing pushpin.

3:16: And you’re one of the first people to engage with the idea of security against disappointment aren’t you? This time it is not about protecting citizens from crime, but about generally opening up opportunities for them to plan their lives and to put those plans into action? The current mess that is the Trump government is an example of a government violating this principle of security it seems to me.

JB: In order to form a clear idea of the whole extent which ought to be given to the principle of security, it is necessary to consider, that man is not like the brutes, limited to the present time, either in enjoyment or suffering, but that he is susceptible of pleasure and pain by anticipation, and that it is not enough to guard him against an actual loss, but also to guarantee to him, as much as possible, his possessions against future losses.

The idea of his security must be prolonged to him throughout the whole vista that his imagination can measure. This disposition to look forward, which has so marked an influence upon the condition of man, may be called expectation—expectation of the future. It is by means of this we are enabled to form a general plan of conduct; it is by means of this, that the successive moments which compose the duration of life are not like insulated and independent points, but become parts of a continuous whole. Expectation is a chain which unites our present and our future existence, and passes beyond ourselves to the generations which follow us.

The sensibility of the individual is prolonged through all the links of this chain. The principle of security comprehends the maintenance of all these hopes; it directs that events, inasmuch as they are dependent upon the laws, should be conformed to the expectations to which the laws have given birth.

What is a Trump?

3:16: The first fascist president of the USA! Doesn’t utilitarianism threaten minorities by emphasising the happiness of the majority in a community?

JB: No. Be the community in question what it may, divide it into two unequal parts, call one of them the majority, the other the minority, lay out of the account the feelings of the minority, include in the account no feelings but those of the majority, the result you will find is that to the aggregate stock of happiness of the community, no addition at all is made. If the happiness of the minority is not taken into account, the sum of happiness is not increased; it is only shifted from one set of persons to another.

3:16: You often distinguish between subordinate ends, principles, and maxims as parts of his utilitarian framework and legislative theory. And break down how moral and legal rules operate, how smaller goals relate to ultimate ends, and how general principles guide action. Can you say something about these things?

JB: The principle of utility is the foundation of the present work: it will be proper therefore at the outset to give an explicit and determinate account of what is meant by it. By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words, to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever; and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government.

All other principles, or subordinate ends, must be referred to the principle of utility: they are only right in so far as they conform to it, and wrong in so far as they deviate from it. The various subordinate maxims, such as those of justice, benevolence, veracity, and so on, are only so many applications of the principle of utility to particular cases. All other principles, or subordinate ends, must be referred to the principle of utility: they are only right in so far as they conform to it, and wrong in so far as they deviate from it.

The various subordinate maxims, such as those of justice, benevolence, veracity, and so on, are only so many applications of the principle of utility to particular cases. The subordinate ends of government-security, subsistence, abundance, equality-are all but branches of the main end, the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Each is to be pursued only so far as it does not conflict with the general happiness. The various subordinate ends, such as justice, order, and tranquillity, are not ends in themselves, but only so far as they are conducive to the main end, which is the greatest happiness of the community.

3:16: Do you think that poverty deeply affects the ability to satisfy basic needs, that the marginal benefit of resources is far greater for the poor, and that poverty can undermine both independence and human flourishing?

JB: No longer enslaved or made dependent by force of law, the great majority are so by force of poverty; they are still chained to a place, to an occupation, and to conformity with the will of an employer, and debarred, by the accident of birth both from the enjoyments, and from the mental and moral advantages, which others inherit without exertion and independently of desert. That this is an evil equal to almost any of those against which mankind have hitherto struggled, the poor are not wrong in believing.

3:16: You think legislating against it can be a bit of a vicious circle if you’re not careful though don’t you?

JB: Well Richard, in his endeavour to provide a remedy against deficiency in regard to subsistence, the legislator finds himself all along under the pressure of this dilemma-forbear to provide supply, death ensues, and it has you for its author; provide supply, you establish a bounty upon idleness, and you thus give increase to the deficiency which it is your endeavour to exclude.

3:16: You seem to put issues of penal, constitutional and civil law together which is interesting. Is that right?

JB: Richard, as the distinction between the penal branch of the law and the civil is so familiar, I had all along taken for granted that the line of separation between those objects might be traced within the compass of a page or two. When I came to make the experiment, I found that this such separation could scarcely be said as yet to exist: and that to set up one of my own in such manner as to answer as nearly as possible the purposes for which the verbal distinction in words is made, would involve a multitude of problems of the most intricate kind which nobody seemed had hitherto seems to have thought of solving.

I found in short that the substance matter body of the penal law was almost inextricably interwoven with the civil on one hand and the constitutional on the other: and it became necessary to carry pervade my eye through the whole mass of the law in every direction in order ere I could to disentangle from the rest the part to which I had at first originally intended to confine myself.

3:16: Well that helps me understand why punishment plays such a big role in your philosophy. So as a utilitarian, what’s the role of punishment?

JB: Security. General prevention ought to be the chief end of punishment, as it is its real justification. If we could consider an offence which has been committed as an isolated fact punishment would be useless. It would be only adding one evil to another. But when we consider that an unpunished crime leaves the path of crime open to all those who may have the same motives and opportunities for entering upon it, we perceive that the punishment inflicted on the individual becomes a source of security to all.

3:16: So is punishment preventative?

JB: The object of punishment is not the infliction of pain for its own sake, but the prevention of greater evil to society. Punishment is to be applied with a view to the public good, as a means of deterring offenders and others from committing offenses, and as a method of reforming the offender’s conduct. The punishment must be proportionate to the offense, neither too severe nor too lenient, to be most effective in securing obedience to the law. If the punishment be too light, it will fail to deter; if too heavy, it will provoke resistance and injustice. The principle of utility requires that the penalty be so adjusted as to produce the greatest happiness in the community, by preventing crime with the least possible pain to the offender. This proportion is the fundamental maxim of all penal policy. The chief end of all punishments is the prevention of crime.

3:16: You’re a great advocate of penal reform aren’t you and your ideas about the Panoptican is a big part of this? Can you tell us about this idea and why you think it a great idea. What is a Panoptican?

JB: A building circular, a machine for grinding rogues honest.. The prisoners in their cells, occupying the circumference-The officers in the centre. By blinds and other contrivances, the Inspectors concealed... from the observation of the prisoners: hence the sentiment of a sort of omnipresence -The whole circuit reviewable with little, or... without any, change of place. One station in the inspection part affording the most perfect view of every cell. The essence of the Panopticon is that each inmate is alone, visible at all times to the staff from a lit central watchtower.

3:16: Why the emphasis on this constant scrutiny?

JB: The more constantly the persons to be inspected are under the eyes of the persons who should inspect them, the more perfectly will the purpose of the establishment have been attained.

3:16: And you see this as architecture itself doing a lot of the reformist work?

JB: Yes. Morals reformed – health preserved – industry invigorated – instruction diffused – public burdens lightened – Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock – the Gordian knot of the Poor-Laws are not cut, but untied – all by a simple idea in Architecture!

3:16: And you also think this idea could and should be extended to institutions beyond those of prisons don’t you?

JB: It will be found applicable, I think, without exception, to all establishments whatsoever, in which, within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspection. No matter how different or even opposite the purpose: whether it be that of punishing the incorrigible, guarding the insane, reforming the vicious, confining the suspected, employing the idle, maintaining the helpless, curing the sick, instructing the willing in any branch of industry, or training the rising race in the path of education.

3:16: Overall then, are you intent upon changing our system of laws and government – including introducing the Panoptican idea, so that they’re in step with the principles of utility?

JB: In my ‘Principles of Legal Policy’ the object of it is to trace out a new model for the Laws: of my own country you may imagine, in the first place: but keeping those of other countries all along in view. To ascertain what the Laws ought to be, in form and tenor as well as in matter: and that elsewhere as well as here. The repose of Grotius and Puffendorf and Barbeyrac and Burlamaqui I would never wish to see disturbed. I have built solely on the foundation of utility, laid as it is by Helvetius.

3:16: You’re very critical of Blackstone’s view of the legal system aren’t you?

JB: The fool had stuck himself up one day, with great gravity, in the King's throne; with a stick, by way of a sceptre, in one hand, and a ball in the other: being asked what he was doing? he answered 'reigning'. Much of the same sort of reign, I take it would be that of our Blackstone's democracy. Blackstone was all caution and coldness. Blackstone's status will remain, his memory will remain, but his Commentaries will be forgotten.

3:16: You think he idealises law and so makes critics of it and government impossible?

JB: Yes. All mankind, Blackstone says, will agree that government should be reposed in persons who are most likely to have the qualities the perfection of which are among the most essential requisites to government. Well, if they give these considerations their due weight, they will acknowledge that if there are some institutions which it is ‘arrogance’ to attack, there may be others which it is effrontery to defend.

3:16: And you reject the idea of a social contract that Blackstone finds important?

JB: It made no sense to posit the notion of a natural society being transformed into a political society by means of a social contract.

3:16: Do you support the Enlightenment spirit of the Encyclopedists over in revolutionary France?

JB: To the National Convention of France I offered advice as an Englishman who has experience of parliamentary government, on how they might best conduct their affairs in the sense of promoting the general happiness of the community for which they were responsible.

3:16: You corresponded with Voltaire and admired Diderot although you weren’t impressed by the revolution’s talk of natural rights, as we’ve noted earlier. You’re an early advocate of anti slavery and anti-colonialism aren’t you and told the revolutionary leaders to get rid of theirs didn’t you?

JB: Emancipate your colonies Richard! Colonialism is an aristocratical abomination: it is a cluster of aristocratical abominations.

3:16: As a quick note, David Hume’s Enquiry was an inspiration for your work alongside Locke and Helvetius wasn’t it?

JB: Yes, reading it, it felt as if scales had fallen from my eyes.

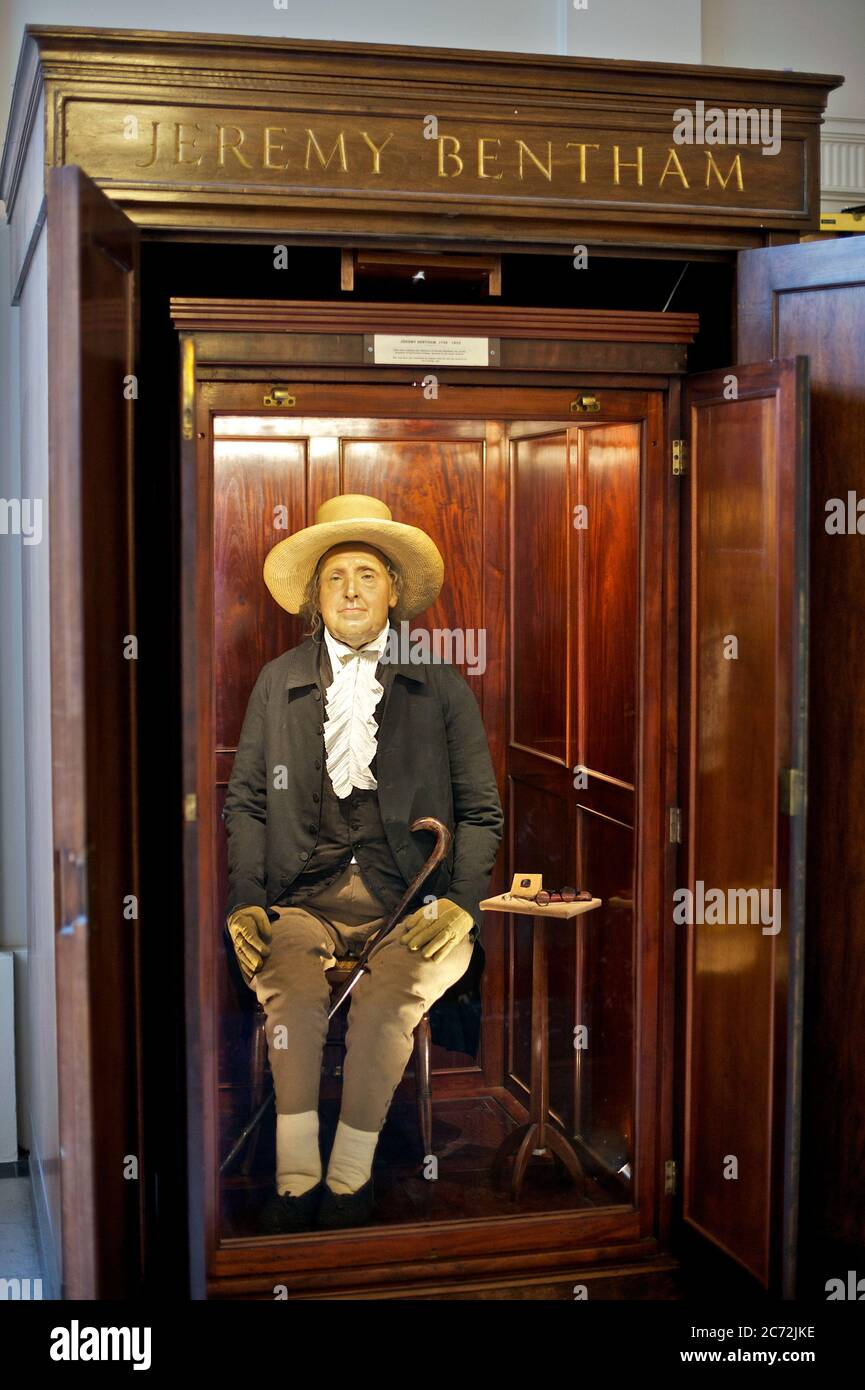

3:16: You have made some interesting arrangements for what should happen to your body once you die haven’t you?

JB: Yes Richard. My body I give to my dear friend Doctor Southwood Smith to be disposed of in a manner hereinafter mentioned, and I direct ... he will take my body under his charge and take the requisite and appropriate measures for the disposal and preservation of the several parts of my bodily frame in the manner in the paper annexed to this my will and at the top of which I have written Auto Icon. The skeleton he will cause to be put together in such a manner as that the whole figure may be seated in a chair usually occupied by me when living, in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought in the course of time employed in writing.

The body so clothed, together with the chair and the staff in the my later years bourne by me, he will take charge of and for containing the whole apparatus he will cause to be prepared an appropriate box or case and will cause to be engraved in conspicuous characters on a plate to be affixed thereon and also on the labels on the glass cases in which the preparations of the soft parts of my body shall be contained ... my name at length with the letters ob: followed by the day of my decease.

If it should so happen that my personal friends and other disciples should be disposed to meet together on some day or days of the year for the purpose of commemorating the founder of the greatest happiness system of morals and legislation my executor will from time to time cause to be conveyed to the room in which they meet the said box or case with the contents therein to be stationed in such part of the room as to the assembled company shall seem meet.

3:16: Wow. Ok, finally then, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your world?

JB:

Helvetius

Voltaire

Hutcheson

Beccaria

Locke

Other Interviews:

Sidgwick, Diderot, Sade, Herbart, Helmholtz, Heine, Rousseau, Cohen, Machiavelli, LaMettrie, Smith,

Buchner, Lange, Newton, Berkeley, Hobbes, Locke, Cudworth, Hume, Leibniz, Leporin Erxleben, Fichte, Schiller, Herder, Kierkegaard, Schelling, Kant, Dilthey, Marx, Descartes, Hegel,

About the Author

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.