Exclusive 3:16am Interview With de Sade

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814) is a French writer, libertine, political activist and nobleman best known for his libertine novels and imprisonment for sex crimes, blasphemy and pornography. His works include novels, short stories, plays, dialogues, and political tracts. Some of these were published under his own name during his lifetime, but most appeared anonymously or posthumously. Here he is interviewed about his philosophical ideas.

3:16: What made you interested in philosophy?

Marquis de Sade: Thinking is my sole consolation in life; it alleviates all my sufferings in prison, it composes all my pleasures in the world outside, it is dearer to me than life itself.

3:16: You are challenging as a thinker and you find the thinking of others unhelpful don’t you?

DS: Yes Richard, not my manner of thinking but the manner of thinking of others has been the source of my unhappiness. The reasoning man who scorns the prejudices of simpletons necessarily becomes the enemy of simpletons, he must expect as much, and laugh at the inevitable.

3:16: And this is why you have been imprisoned and why many people disapprove of your thinking. Rousseau said any girl who reads but a single page of Justine will be lost. Napoleon said it is the most abominable book ever engendered by the most depraved imagination - and many seem to agree with him that no one should read your stuff.

DS: My manner of thinking, so you say, cannot be approved. Do you suppose I care? A poor fool indeed is he who adopts a manner of thinking for others! My manner of thinking stems straight from my considered reflections; it holds with my existence, with the way I am made. It is not in my power to alter it; and were it, I’d not do so.

3:16: You are famous for your extreme libertine philosophy of sadism, but it’s foundation is your commitment to the liberty and equality of Republicanism isn’t it?

DS: Yes Richard: new government will require new manners. That the citizens of a free State conduct themselves like a despotic king’s slaves is unthinkable: the differences of their interests, of their duties, of their relations amongst one another essentially determine an entirely different manner of behaving in the world; a crowd of minor faults and of little social indelicacies, thought of as very fundamental indeed under the rule of kings whose expectations rose in keeping with the need they felt to impose curbs in order to appear respectable and unapproachable to their subjects, are due to become as nothing with us; other crimes with which we are acquainted under the names of regicide and sacrilege, in a system where kings and religion will be unknown, in the same way must be annihilated in a republican State.

In according freedom of conscience and of the press, consider, citizens—for it is practically the same thing—whether freedom of action must not be granted too: excepting direct clashes with the underlying principles of government, there remain to you it is impossible to say how many fewer crimes to punish, because in fact there are very few criminal actions in a society whose foundations are liberty and equality. Matters well weighed and things closely inspected, only that is really criminal which rejects the law; for Nature, equally dictating vices and virtues to us, in reason of our constitution, yet more philosophically, in reason of the need Nature has of the one and the other, what she inspires in us would become a very reliable gauge by which to adjust exactly what is good and bad.

3:16: And adjusting what we take to be good and bad is exactly what your philosophy examining libertine passions is attempting to do isn’t it, something that your critics don’t always consider?

DS: Ah, Richard, dangerous moments there are when the physical self is fired by the mind’s extravagances. . . .There is no better way to familiarize oneself with death than through the medium of a libertine idea. They declaim against the passions without bothering to think that it is from their flame philosophy lights its torch. You shall know nothing if you have not known everything, and if you are timid enough to stop with what is natural, Nature will elude your grasp forever.

3:16: Some might think your Republican libertine philosophy is basically an excuse for anarchy and cruelty without constraint?

DS: Humanity, fraternity, benevolence prescribe our reciprocal obligations, and let us individually fulfill them with the simple degree of energy Nature has given us to this end; let us do so without blaming, and above all without punishing, those who, of chillier temper or more acrimonious humor, do not notice in these yet very touching social ties all the sweetness and gentleness others discover therein.

3:16: You don’t think there are universal laws applicable to all do you?

DS: It is a terrible injustice to require that men of unlike character all be ruled by the same law: what is good for one is not at all good for another. That we cannot devise as many laws as there are men must be admitted; but the laws can be lenient, and so few in number, that all men, of whatever character, can easily observe them. Furthermore, I would demand that this small number of laws be of such a sort as to be adaptable to all the various characters.

3:16: It’s your view that whatever Nature permits be lawful, and the law perverse because it ignores Nature and is therefore impersonal. In this you are opposed to Kantian Enlightenment philosophy?

DS: Yes. Man receives his impressions from Nature, who is able to forgive him this act; the law, on the contrary, always opposed as it is to Nature and receiving nothing from her, cannot be authorized to permit itself the same extravagances: not having the same motives, the law cannot have the same rights.

3:16: Some think your libertinism is merely an excuse for criminal murderous behaviour.

DS: Well Richard, I am a libertine, but I am neither a criminal nor a murderer, and since I am compelled to set my apology next to my vindication, I shall therefore say that it might well be possible that those who condemn me as unjustly as I have been might themselves be unable to offset their infamies by good works as clearly established as those I can contrast to my errors. I am a libertine, but three families have for five years lived off my charity, and I have saved them from the farthest depths of poverty. I am a libertine, but I have saved a deserter from death, a deserter abandoned by his entire regiment and by his colonel. I am a libertine, but at Evry, I saved a child—at the risk of my life—who was on the verge of being crushed beneath the wheels of a runaway horse-drawn cart, by snatching the child from beneath it. I am a libertine, but I have never compromised my wife’s health.

Nor have I been guilty of the other kinds of libertinage so often fatal to children’s fortunes: have I ruined them by gambling or by other expenses that might have deprived them of, or even by one day foreshortened, their inheritance? Have I managed my own fortune badly, as long as I had a say in the matter? In a word, did I in my youth herald a heart capable of the atrocities of which I today stand accused.

3:16: A key question you raise is the nature of happiness? How do you approach this question?

DS: Who are you, and what are you after in this world? Only too often I behold you asleep, inert, or just barely alive, coming and going like some organic statue. This statue—is it you? No, you would have yourself a conscious being, as conscious as possible, and rational. You seek happiness, which increases consciousness tenfold. What happiness? Ordinarily it is located in pleasure and in love. All well and good. But one thing: avoid confusing the two. To love and to taste pleasure are essentially different; proof thereof is that one loves every day without tasting pleasure, and that one still more frequently tastes pleasure without loving.

Now, while an indisputable pleasure goes with the gratification of the senses, love, you will admit, is accompanied by nuisances and troubles of every sort. ‘But moral pleasures,’ do you say? Indeed. Do you know of a single one that originates anywhere but in the imagination? Only grant me that freedom is this imagination’s sole sustenance; and the joys it dispenses to you are keen to the extent the imagination is unhampered by reins or laws. What? Fix some a priori rule upon the imagination? Why, is it not imprudent merely to speak of rules? Leave the imagination free to follow its own bent.

3:16: Are we naturally selfish – putting our own pleasure before those of others?

DS: Well Richard, from Nature we obtain abundant information about ourselves, and precious little about others. About the woman you clasp in your arms, can you say with certainty that she does not feign pleasure? About the woman you mistreat, are you quite sure that from abuse she does not derive some obscure and lascivious satisfaction? Let us confine ourselves to simple evidence : through thoughtfulness, gentleness, concern for the feelings of others we saddle our own pleasure with restrictions, and make this sacrifice to obtain a doubtful result. Rather, is it not normal for a man to prefer what he feels to what he does not feel? And have we ever felt a single impulse from Nature bidding us to give others a preference over ourselves?

3:16: Some would say that that is immoral.

DS: A word or two about morals, if you like. Are you then unaware that murder was honored in China, rape in New Zealand, theft in Sparta? That man you watch being drawn and quartered in the market place, what has he done? He ventured to acquit himself in Paris of some Japanese virtue. That other whom we have left to rot in a dank dungeon, what was his crime? He read Confucius. No, Richard, the vice and virtue they shout about are words which, when you scan them for their meaning, never yield anything but local ideas. At best, and if you consider them rightly, they tell you in which country you should have been born. Moral science is simply geography misconstrued.

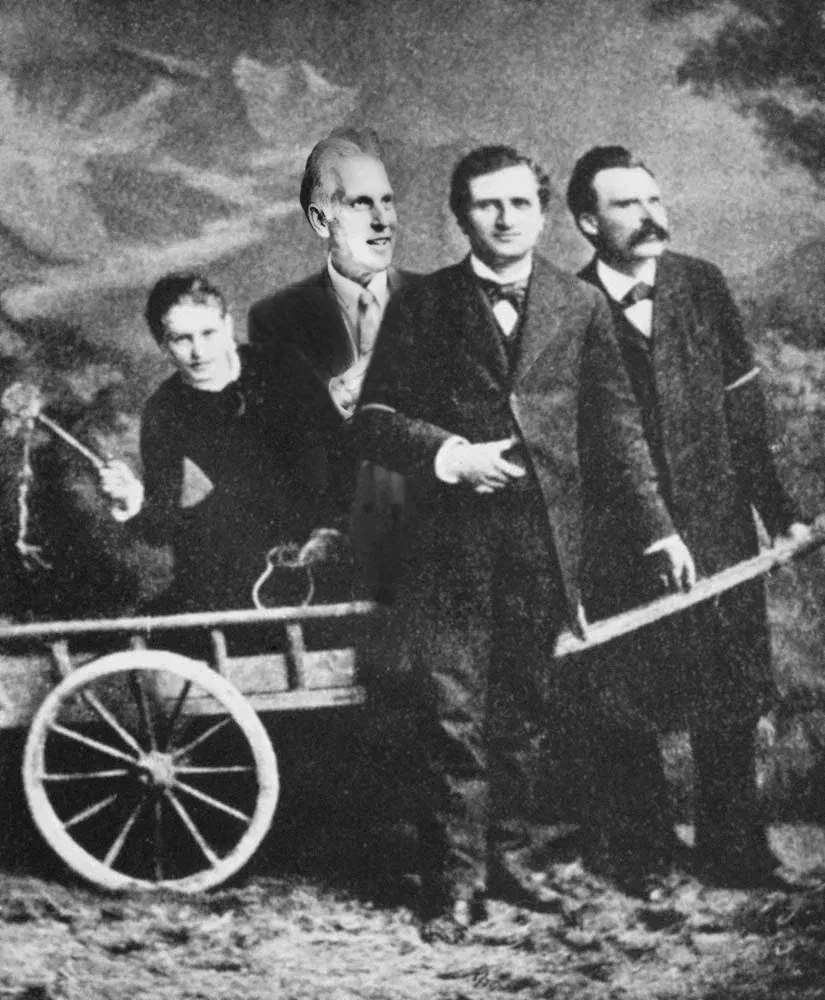

3:16: You construe moral formation in terms of a genealogy very like Nietzsche’s don’t you?

DS: From earliest childhood, we hear nothing but lectures on charity and goodness. These virtues, as you know, were invented by Christians. Do you know why? The answer is, that being themselves slaves, powerless and destitute, for their pleasures—for their very survival—they could look nowhere but to their masters’ bounty. Their whole interest lay in persuading those masters to behave charitably. To that end they employed all their parables, their legends, their sayings, all their seductive wiles. Those masters, great fools that they were, let themselves be taken in. So much the worse for them. Who the hell’s Nietzsche?

3:16: Oh he’s a philosopher too. So is it your claim that we can ignore the values because they’re not what they claim to be?

DS: Yes, we philosophers, with more experience behind us, by pursuing pleasure in the manner we wish and pursuing it with all our might, do exactly what your beloved slaves practiced, and not what they preached.

3:16: Can we actually do that without feeling pangs of remorse?

DS: Haven’t you already noticed? The only deeds man is given to repent are those he is not accustomed to performing. Get into the habit, and there’s an end to qualms and regrets; whereas one crime may perhaps leave us uneasy, ten, twenty crimes do not.

3:16: What about the idea of social contract as the basis of morality?

DS: Let us see. You claim that in the earliest stage of their societies men concluded a pact along these lines: ‘I shall do you no ill so long as you do me none.’ I would simply draw your attention to one thing, that a pact of this kind presupposes the equality of the contracting parties. I renounced doing you harm; which means I was free to harm you up until then. I renounce harming you now; this means I have been free to harm you up until now. Imagine however that you are delivered utterly into my power the way a slave is into his master’s, the way a man condemned to die is handed over to his executioner. How could it possibly occur to me to strike a bargain with you whereby you acquire illusory rights through my foregoing real rights? If you are unable to hurt me, why in the world should I fear you and deprive myself for your sake? But let us go still further. You will grant me that everybody draws his pleasure from the exercise of his particular faculties and attributes: like the athlete from wrestling, and the generous man from his benevolent actions; thus also the violent man from his very violence. If you are completely in my power, it is from oppressing you that I am going to reap my greatest joys.

3:16: So you think true Enlightenment thinking, once denuded of theistic constraints, all purely a matter of game theoretic calculation – two rational agents working out to selfishly optimize consequences?

DS: Quite right Richard. Observe this also: as the mighty man takes pleasure from the exercise of his strength, so does the gentle or the weak man profit from his compassion. He too has a good time. It is his own way of having a good time; and that is his business. Why the devil must I further reward him for the enjoyment he gives himself?

3:16: So this is the way civilization develops? Should we then forget about what people do naturally?

DS: Civilization has changed the aspect of Nature; civilization nonetheless respects her laws. The rich of today are just as ferocious in their exploitation of the poor as the violent used to be in their vexation of the helpless. All these financiers, all these important personages you see would bleed the entire population dry if they fancied its blood might yield a few grains of gold.

3:16: So what kind of life should we live in the light of all this?

DS: An absurd one. You are forewarned of nothing, and you are punished for everything. ... Yesterday, though you made no mistakes, you were given the whip. You shall soon receive it again for having committed some. Above all, don’t ever get the idea that you are innocent. The essential thing is never to refuse anything, to be ready for everything, and even so, though this be the best course to follow, it does not much insure your safety. To be honest Richard, my neighbors’ passions frighten me infinitely less than do the law’s injustices, for my neighbors’ passions are contained by mine, whilst nothing constrains, nothing checks the injustices of the law.

3:16: Don’t you think there’s something morally good about constraining ones desires?

DS: My imagination has only been pricked the more by the pleasures I thought to deprive myself of. I have discovered that when it is a question of someone like me, born for libertinage, it is useless to think of imposing limits or restraints upon oneself—impetuous desires immediately sweep them away. I am an amphibious creature: I love everything, everyone, whatever it is, it amuses me; I should like to combine every species.

3:16: Are there no natural virtues?

DS: Virtue is but a chimera whose worship consists exclusively in perpetual immolations, in unnumbered rebellions against the temperament’s inspirations. Can such impulses be natural? Does Nature recommend what offends her?

3:16: But aren’t some people naturally virtuous?

DS: Ah, Richard, theirs are not, if you wish, the same passions as ours; but they harken to others, and often more contemptible.

3:16: Like what?

DS: There is ambition, there pride, there you find self-seeking, and often, again, it is a question of mere constitutional numbness, of torpor: there are beings who have no urges. Are we, I ask, to revere such as them? No; the virtuous woman acts, or is inactive, from pure selfishness. Is it then better, wiser, more just to perform sacrifices to egoism than to one’s passions? As for me, I believe the one far worthier than the other, and who heeds but this latter voice is far better advised, no question of it, since it only is the organ of Nature, while the former is simply that of stupidity and prejudice.

3:16: But what about feelings of pity?

DS: What can it be for whosoever has no belief in religion? And who is able to have religious beliefs? Come now, Richard, let’s reason systematically. Do you not call religion the pact that binds man to his Creator and which obliges him to give his Creator evidence, by means of worship, of his gratitude for the existence received from this sublime author?

3:16: It could not be better defined, I’ll give you that.

DS: Thanks Richard! Now, if it is demonstrated that man owes his existence to nothing but Nature’s irresistible schemes; if man is thus proven as ancient in this world as is ancient the globe itself, he is but as the oak, as grain, as the minerals to be found in the earth’s entrails, who are bound only to reproduce, reproduction being necessitated by the globe’s existence, which owes its own to nothing whatsoever; if it is demonstrated that this God, whom fools behold as the author and maker of all we know there to be, is simply the ne plus ultra of human reason, merely the phantom created at the moment this reason can advance its operations no further; if it is proven that this God’s existence is impossible, and that Nature, forever in action, forever moving, has of herself what it pleases idiots to award God gratuitously; if it is certain that this inert being’s existence, once supposed, he would be of all things the most ridiculous, since he would have been useful only one single time and, thereafter and throughout millions of centuries, fixed in a contemptible stillness and inactivity; that, supposing him to exist as religions portray him to us, this would be the most detestable of creatures, since it would be God who permits evil to be on earth while his omnipotence could prevent it; if, I say, all that is admitted to be proven, as incontestably it is, do you believe, Richard, that it is a very necessary virtue, this piety which binds man to an idiotic, insufficient, atrocious, and contemptible Creator?

3:16: So you’re an atheist on principle?

DS: To believe therein one must first have gone out of one’s mind. Fruit of the terror of some and of the frailty of others, that abominable phantom, Richard, is of no use to the terrestrial scheme and would infallibly be injurious to it, since the will of God would have to be just and should never be able to ally itself to the essential injustices decreed by Nature; since He would constantly have to will the good, while Nature must desire it only as compensation for the evil which serves her laws; since it would be necessary that he, God, exert his influence at all times, while Nature, one of whose laws is this perpetual activity, could only find herself in competition with and unceasing opposition to him.

3:16: What if one was to argue that God and Nature were one?

DS: ’Tis an absurdity. The thing created cannot be the creative being’s equal. Might the pocket watch be the watchmaker?

3:16: Well what if someone was to argue that everything is God, that Nature is nothing.

DS: Another stupidity! There are necessarily two things in the universe: the creative agent and the being created; now, to identify this creative agent is the single task before us, the one question to which one has got to provide a reply. If matter acts, is moved by combinations unknown to us, if movement is inherent in Nature; if, in short, she alone, by reason of her energy, is able to create, produce, preserve, maintain, hold in equilibrium within the immense plains of space all the spheres that stand before our gaze and whose uniform march, unvarying, fills us with awe and admiration, what then becomes of the need to seek out a foreign agent, since this active faculty essentially is to be found in Nature herself, who is naught else than matter in action?

Do you suppose your deific chimera will shed light upon anything ? I defy anyone to prove him to me. It being supposed that I am mistaken upon matter’s internal faculties, I have before me, at least, nothing worse than a difficulty. What do you do for me when you offer your God to me? Nothing but offering one more god. And how would you have me acknowledge as cause of what I do not understand, something that I understand even less?

3:16: So you think all religions, including Christianity, are ridiculous for republican lovers of freedom and equality?

DS: Yes. What do I see in the God of that infamous sect if not an inconsistent and barbarous being, today the creator of a world of destruction he repents of tomorrow; what do I see there but a frail being forever unable to bring man to heel and force him to bend a knee.

3:16: Ok, so you think the religion is a fraud – but couldn’t there be something to be said for the values it promotes?

DS: Like what?

3:16: Chastity?

DS: Are you joking? Are you going to respect the obligation to combat all Nature’s operations, will you sacrifice them all to the vain and ludicrous honor of never having had a weakness?

3:16: Ok, I threw that in just because of your focus on sex. But what about charity and benevolence?

DS: Benevolence is surely rather pride’s vice than an authentic virtue in the soul; never is it with the single intention of performing a good act, but instead ostentatiously that one aids one’s fellow man; one would be most annoyed were the alms one has just bestowed not to receive the utmost possible publicity.

3:16: But shouldn’t we perform good acts?

DS: Nature has endowed each of us with a capacity for kindly feelings: let us not squander them on others. What to me are the woes that beset others? Have I not enough of my own without afflicting myself with those that are foreign to me? May our sensibility’s hearth warm naught but our pleasures! Let us feel when it is to their advantage; and when it is not, let us be absolutely unbending. From this exact economy of feeling, from this judicious use of sensibility, there results a kind of cruelty which is sometimes not without its delights. One cannot always do evil; deprived of the pleasure it affords, we can at least find the sensation’s equivalent in the minor but piquant wickedness of never doing good.

3:16: So what do you make of the distinction between vice and virtue?

DS: these words vice and virtue contain for us naught but local ideas. There is no deed, in whatever the unusual form you may imagine it, which is really criminal, none which may be really called virtuous. All is relative to our manners and the climate we inhabit; what is a crime here is often a virtue several hundred leagues hence, and the virtues of another hemisphere might well reverse themselves into crimes in our own. There is no horror that has not been consecrated somewhere, no virtue that has not been blasted. When geography alone decides whether an action be worthy of praise or blame, we cannot attach any great importance to ridiculous and frivolous sentiments, but rather should be impeccably armed against them, to the point, indeed, where we fearlessly prefer the scorn of men if the actions which excite it are for us sources of even the mildest voluptuousness.

3:16: But aren’t there some things that are thought evil everywhere – killing an innocent baby just for a laugh for example?

DS: Such horrors are somewhere tolerated. They have been honored, crowned, beheld as exemplary deeds, whereas in other places, humaneness, candor, benevolence, chastity, in brief, all our virtues have been regarded as monstrosities. Virtue, vice, all are confounded in the grave.

3:16: So you consider all evils not moral but more like natural calamities, like earthquakes and such. So a murder is just an accident and nothing to do with morality?

DS: Wars, plagues, famines, murders would no longer be but accidents, necessary to Nature’s laws, and man, whether instrumental to or the object of these effects, would hence no longer be more a criminal in the one case than he would be a victim in the other.

3:16: What about incest?

DS: How, after the vast afflictions our planet sometime knew, how was the human species otherwise able to perpetuate itself, if not through incest? Of which we find, do we not, the example and the proof itself in the books Christianity respects most highly. By what other means could Adam’s family? and that of Noah have been preserved? Sift, examine universal custom: everywhere you will detect incest authorized, considered a wise law and proper to cement familial ties.

3:16: Abortion?

DS: The right is natural .. . it is incontestable. As we have broadened the horizon of our rights, we have recognized that we are perfectly free to take back what we only gave up reluctantly, or by accident, and that it is impossible to demand of any individual whomsoever that he become a father or a mother against his will; that this creature whether more or less on earth is not of very much consequence, and that we become, in a word, as certainly the masters of this morsel of flesh, however it be animated, as we are of the nails we pare from our fingers, or the excrements we eliminate through our bowels, because the one and the other are our own, and because we are absolute proprietors of what emanates from us.

Having had elaborated for you, Richard, the very mediocre importance the act of murder has here on earth, you have been obliged to see of what slight consequence, similarly, must be everything that has to do with childbearing even if the act is perpetrated against a person who has arrived at the age of reason; unnecessary to embroider upon it: your high intelligence adds its own arguments to support my proofs. Peruse the history of the manner of all the world’s peoples and you will unfailingly see that the practice is global; you will finally be convinced that it would be sheer imbecility to accord a very indifferent action the title of evil.

3:16: So nothing’s immoral at all?

DS: It’s our pride prompts us to elevate murder into crime. Esteeming ourselves the foremost of the universe’s creatures, we have stupidly imagined that every hurt this sublime creature endures must perforce be an enormity; we have believed Nature would perish should our marvelous species chance to be blotted out of existence.

3:16: Are virtues nevertheless useful?

DS: Virtues are of some usefulness in civil life.

3:16: So faking virtues is useful?

DS: Let’s not doubt that the appearance alone is quite sufficient to him: he has got that, and he possesses all he needs. Since one does nothing in this world but pinch, rub, and elbow others, is it not enough that they display their skin to us? Let us more over be well persuaded that of the practice of virtue we can at the very most say that it is hardly useful save to him who has it; others reap so little there from that so long as the man who must live amongst other men appears virtuous, it matters not in the slightest whether he is so in fact or not. Deceit, furthermore, is almost always an assured means to success; he who possesses deceit necessarily begins with an advantage over whosoever has commerce or correspondence with him: dazzling him with a false exterior, he gains his confidence; convince others to place trust in you, and you have succeeded.

3:16: You are famous for defending the idea of getting pleasure from cruelty. It’s even been named after you. What’s the argument?

DS: Have we ever felt a single natural impulse advising us to prefer others to ourselves, and is each of us not alone, and for himself in this world? ’Tis a very false tone you use when you speak to us of this Nature which you interpret as telling us not to do to others what we would not have done to us; such stuff never came but from the lips of men, and weak men. Never does a strong man take it into his head to speak that language. They were the first Christians who, daily persecuted on account of their ridiculous doctrine, used to cry at whosoever chose to hear: “Don’t burn us, don’t flay us! Nature says one must not do unto others that which unto oneself one would not have done!” Fools! How could Nature, who always urges us to delight in ourselves, who never implants in us other instincts, other notions, other inspirations, how could Nature, the next moment, assure us that we must not, however, decide to love ourselves if that might cause others pain? Ah! believe me, Richard, believe me, Nature, mother to us all, never speaks to us save of ourselves; nothing has more of the egoistic than her message, and what we recognize most clearly therein is the immutable and sacred counsel: prefer thyself, love thyself, no matter at whose expense.

3:16: Ok, but why does that endorse cruelty?

DS: Cruelty, very far from being a vice, is the first sentiment Nature injects in us all. The infant breaks his toy, bites his nurse’s breast, strangles his canary long before he is able to reason; cruelty is stamped in animals, in whom, as I think I have said, Nature’s laws are more emphatically to be read than in ourselves; cruelty exists amongst savages, so much nearer to Nature than civilized men are; absurd then to maintain cruelty is a consequence of depravity. I repeat, the doctrine is false. Cruelty is natural.

3:16: Then why are so many against it?

DS: Repeal your laws, do away with your constraints, your chastisements, your habits, and cruelty will have dangerous effects no more, since it will never manifest itself save when it meets with resistance, and then the collision will always be between competing cruelties; it is in the civilized state cruelty is dangerous, because the assaulted person nearly always lacks the force or the means to repel injury; but in the state of uncivilization, if cruelty’s target is strong, he will repulse cruelty; and if the person attacked is weak, why, the case here is merely that of assault upon one of those persons whom Nature’s law prescribes to yield to the strong—'tis all one, and why seek trouble where there is none?

3:16: According to you not all cruelty gives pleasure do they? You distinguish between two kinds don’t you?

DS: Yes Richard, in general, we distinguish two sorts of cruelty: that resulting from stupidity, which, never reasoned, never analyzed, assimilates the unthinking individual into a ferocious beast: this cruelty affords no pleasure, for he inclined to it is incapable of discrimination. The other species of cruelty, fruit of extreme organic sensibility, is known only to them who are extremely delicate in their person, and the extremes to which it drives them are those determined by intelligence and niceness of feeling; this delicacy, so finely wrought, so sensitive to impressions, responds above all, best, and immediately to cruelty; it awakens in cruelty, cruelty liberates it. How few are able to grasp these distinctions! ...and how few there are who sense them! They exist nonetheless.

3:16: Do you think women more likely to be able to find pleasure in cruelty than men?

DS: Yes Richard, this second kind of cruelty you will most often find in women. Study them well: you will see whether it is not their excessive sensitivity that leads them to cruelty; you will see whether it is not their extremely active imagination, the acuity of their intelligence that renders them criminal, ferocious; oh, they are charming creatures, every one of them; and not one of the lot cannot turn a wise man into a giddy fool if she tries; unhappily, the rigidity, or rather the absurdity, of our customs acts as no encouragement to their cruelty; they are obliged to conceal themselves, to feign, to cover over their propensities with ostensible good and benevolent works which they detest to the depths of their soul; only behind the darkest curtain, by taking the greatest precautions, aided by a few dependable friends, are they able to surrender to their inclinations.

3:16: What about the idea that women are by nature nurturing and oriented to breed and care for babies?

DS: Good God Richard! Women are not born save to produce —which most surely would be the case were this production so dear to Nature—, would it happen that, throughout the whole length of a woman’s life, there are no more than seven years, all the arithmetic performed, during which she is in a state capable of conceiving and giving birth? What! Nature avidly seeks propagation, does she; and everything which does not tend to this end offends her, does it! and out of a hundred years of life the sex destined to produce cannot do so during more than seven years! Nature wishes for propagation only, and the semen she accords man to serve in these reproducings is lost, wasted, misused where ever and as often as it pleases man! He takes the same pleasures in this loss as in useful employment of his seed, and never the least inconvenience! ...

Let us cease to believe in such absurdities: they cause good sense to shudder. Ah! far from outraging Nature, on the contrary—and let us be well persuaded of it —, the sodomite and Lesbian serve her by stubbornly abstaining from a conjunction whose resultant progeniture can be nothing but irksome to her. Let us make no mistake about it, this propagation was never one of her laws, nothing she ever demanded of us, but at the very most something she tolerated.

3:16: So obviously you’re a supporter of gay rights?

DS: We discover a hemisphere, we find sodomy in it. Cook casts anchor in a new world: sodomy reigns there. Had our balloons reached the moon, it would have been discovered there as well. Delicious preference, child of Nature and of pleasure, thou must be everywhere men are to be found, and wherever thou shalt be known, there shall they erect altars to thee!

3:16: Why is friendship better than love?

DS: Fuck, divert yourselves, that’s the essential thing; but be quick to fly from love. There is none but physical good in it, said Buffon, and as a good philosopher he exercised his reason on an understanding of Nature. Provided they remain useful to us let us keep our friends as long as they serve us; forget them immediately we have nothing further from them; ’tis never but selfishly one should love people; to love them for themselves is nothing but dupery.

3:16: And what of gratitude?

DS: Doubtless the most feeble of all the bonds. Is it then for ourselves men are obliging to us? Not a bit of it, my dear; ’tis through ostentation, for the sake of pride. Is it not humiliating thus to become the toy of others’ pride? Is it not yet more so to fall into indebtedness to them? Nothing is more burdensome than a kindness one has received. No middle way, no compromise: you have got to repay it or ready yourself for abuse. Upon proud spirits a good deed sits very heavily: it weighs upon them with such violence that the one feeling they exhale is hatred for their benefactors.

3:16: Is your atheism linked to your Republicanism – do religion and cults enable tyranny?

DS: I equally despise both that empty god impostors have celebrated, and all the farce of religious subtleties surrounding a ridiculous belief: it is no longer with this bauble that free men are to be amused. Let the total extermination of cults and denominations therefore enter into the principles we broadcast throughout all Europe. Let us not be content with breaking scepters; we will pulverize the idols forever: there is never more than a single step from superstition to royalism.

3:16: What do you put in its place?

DS: The statues of Mars, of Minerva, and of Liberty will be set up in the most conspicuous places in the villages; holidays will be celebrated there every year; the prize will be decreed to the worthiest citizen. At the entrance to a secluded wood, Venus, Hymen, and Love, erected beneath a rustic temple, will receive lovers’ homages; there, by the hand of the Graces, Beauty will crown Constancy. More than mere loving will be required in order to pose one’s candidacy for the tiara. It will be necessary to have merited love. Heroism, capabilities, humaneness, largeness of spirit, a proven civism—those are the credentials the lover shall be obliged to present at his mistress’ feet, and they will be of far greater value than the titles of birth and wealth a fool’s pride used to require. Some virtues at least will be born of this worship, whereas nothing but crimes come of that other we had the weakness to profess. This worship will ally itself to the liberty we serve; it will animate, nourish, inflame liberty, whereas theism is in its essence and in its nature the most deadly enemy of the liberty we adore.

3:16: So you agree that once religion and royalism are gone there can be developed these classical civic virtues of liberty? How will this happen?

DS: State education. We must get promptly to the task of training the youth, it must be amongst your most important concerns; above all, build their education upon a sound ethical basis, the ethical basis that was so neglected in your religious education. Rather than fatigue your children’s young organs with deific stupidities, replace them with excellent social principles; instead of teaching them futile prayers which, by the time they are sixteen, they will glory in having forgotten, let them be instructed in their duties toward society; train them to cherish the virtues you scarcely ever mentioned in former times and which, without your religious fables, are sufficient for their individual happiness; make them sense that this happiness consists in rendering others as fortunate as we desire to be ourselves.

3:16: This is a surprising element of the libertine philosophy, but I suppose it makes sense once we see libertinism in the context of your broader Republicanism. You push liberty and equality to its logical conclusion rather than smuggle in the religious values in a secular guise as we find in more or less all other Enlightenment philosophers – the parade case being Kant I guess!

DS: Well put Richard.

3:16: Another surprising element of your philosophy is that you are against capital punishment aren’t you?

DS: One feels, the necessity to make flexible, mild laws and especially to get rid forever of the atrocity of capital punishment, because the law which attempts a man’s life is impractical, unjust, inadmissible. The second reason why the death penalty must be done away with is that it has never repressed crime; for crime is every day committed at the foot of the scaffold.

3:16: You consider the matter of murder and its punishment first from the perspective of Nature and then of men. Let me ask then, from Nature’s perspective, do you think murder is criminal, harmful to society, should republicans decry it and should be repressed by murder?

DS: Death is no more than a change of form, an imperceptible passage from one existence into another, what Pythagoras called metempsychosis. These truths once admitted, I ask whether it can ever be proposed that destruction is a crime? Will you dare tell me that transmutation is destruction? No, surely not. Is murder then a crime against society? But how could that reasonably be imagined? What difference does it make to this murderous society, whether it have one member more, or less? Will its laws, its manners, its customs be vitiated? Has an individual’s death ever had any influence upon the general mass? And after the loss of the greatest battle, what am I saying? after the obliteration of half the world—or, if one wishes, of the entire world—would the little number of survivors, should there be any, notice even the faintest difference in things? No, alas.

Republican mettle calls for a touch of ferocity: if he grows soft, if his energy slackens in him, the republican will be subjugated in a trice. A most unusual thought comes to mind at this point, but if it is audacious it is also true, and I will mention it. A nation that begins by governing itself as a republic will only be sustained by virtues because, in order to attain the most, one must always start with the least. But an already old and decayed nation which courageously casts off the yoke of its monarchical government in order to adopt a republican one, will only be maintained by many crimes; for it is criminal already, and if it were to wish to pass from crime to virtue, that is to say, from a violent to a pacific, benign condition, it should fall into an inertia whose result would soon be its certain ruin. The freest of people are they who are most friendly to murder. Murder, adopted always, always necessary, will have but changed its victims; it has been the delight of some, and will become the felicity of others. Aristotle urged abortion. Briefly, murder is a horror, but an often necessary horror, never criminal, which it is essential to tolerate in a republican State.

Must murder be repressed by murder? Surely not. Let us never impose any other penalty upon the murderer than the one he may risk from the vengeance of the friends or family of him he has killed. “I grant you pardon,” said Louis XV to Charolais who, to divert himself, had just killed a man; “but I also pardon whoever will kill you.” All the bases of the law against murderers may be found in that sublime motto. Is it or is it not a crime? If it is not, why make laws for its punishment? And if it is, by what barbarous logic do you, to punish it, duplicate it by another crime?

3:16: What about suicide?

DS: I will not bother demonstrating here the imbecility of the people who make of this act a crime; those who might have any doubts upon the matter are referred to Rousseau’s famous letter. Nearly all early governments, through policy or religion, authorized suicide.

3:16: This is all flowing from your thinking about Republican freedom and egalitarianism?

DS: All men are born free, all have equal rights: never should we lose sight of those principles; according to which never may there be granted to one sex the legitimate right to lay monopolizing hands upon the other, and never may one of these sexes, or classes, arbitrarily possess the other. Similarly, a woman existing in the purity of Nature’s laws cannot allege, as justification for refusing herself to someone who desires her, the love she bears another, because such a response is based upon exclusion, and no man may be excluded from the having of a woman as of the moment it is clear she definitely belongs to all men. The act of possession can only be exercised upon a chattel or an animal, never upon an individual who resembles us, and all the ties which can bind a woman to a man are quite as unjust as illusory.

3:16: So rape is ok?

DS: It becomes incontestable that we have the right to compel their submission, not exclusively, for I should then be contradicting myself, but temporarily. It cannot be denied that we have the right to decree laws that compel woman to yield to the flames of him who would have her; violence itself being one of that right’s effects, we can employ it lawfully. Indeed! Has Nature not proven that we have that right, by bestowing upon us the strength needed to bend women to our will?

3:16: Woah! This seems like a kind of slavery.

DS: I say then that women, having been endowed with considerably more violent penchants for carnal pleasure than we, will be able to give themselves over to it wholeheartedly, absolutely free of all encumbering hymeneal ties, of all false notions of modesty, absolutely restored to a state of Nature; I want laws permitting them to give themselves to as many men as they see fit; I would have them accorded the enjoyment of all sexes and, as in the case of men, the enjoyment of all parts of the body; and under the special clause prescribing their surrender to all who desire them, there must be subjoined another guaranteeing them a similar freedom to enjoy all they deem worthy to satisfy them.

3:16: Kant says we shouldn’t treat others as ends in themselves. Your Enlightened Republicanism leads to libertinism and concludes we should doesn't it?

DS: Richard; whether it does or does not share my enjoyment, whether it feels contentment or whether it doesn’t, whether apathy or even pain, provided I am happy, the rest is absolutely all the same to me. Why, it is even preferable to have the object experience pain.

3:16: Why?

DS: The idea of seeing another enjoy as he enjoys reduces him to a kind of equality with that other, which impairs the unspeakable charm despotism causes him to feel. This desire to dominate at this moment is so powerful in Nature that one notices it even in animals. What well-made man, in a word, what man endowed with vigorous organs does not desire, in one fashion or in another, to molest his partner during his enjoyment of her? Sex without pain is like food without taste.

3:16: Does radical republican freedom see value in families?

DS: There is nothing more illusory than fathers’ and mothers’ sentiments for their children, and children’s for the authors of their days. Nothing supports, nothing justifies, nothing establishes such feelings.

3:16: You relish the attacks you receive on your libertine philosophy don't you?

DS: The true libertine loves even the reproaches he receives for the unspeakable deeds he has done. Have we not seen some who loved the very tortures human vengeance was readying for them, who submitted to them joyfully, who beheld the scaffold as a throne of glory upon which they would have been most grieved not to perish with the same courage they had displayed in the loathsome exercise of their heinous crimes? There is the man at the ultimate degree of meditated corruption.

3:16: It seems by taking Enlightenment thinking to its extreme conclusion you have discovered a kind of legal anarchy lurking about in Enlightenment thought.

DS: The rule of law is inferior to that of anarchy: the most obvious proof of what I assert is the fact that any government is obliged to plunge itself into anarchy whenever it aspires to remake its constitution. In order to abrogate its former laws, it is compelled to establish a revolutionary regime in which there is no law: this regime finally gives birth to new laws, but this second state is necessarily less pure than the first, since it derives from it. Nature has caused us all to be equals born; if fate is pleased to intervene and upset the primary scheme of things, it is up to us to correct its caprices and, through our own skill, to repair the usurpations of the strongest. So long as our good faith and patience serve only to double the weight of our chains, our crimes will be as Virtues, and we would be fools indeed to abstain from them when they can lessen the yoke wherewith their cruelty bears us down.

3:16: So finally could you summarise for us your philosophical position?

DS: The crux of my philosophy: if the taking of pleasure is enhanced by the criminal character of the circumstances - if, indeed, the pleasure taken is directly proportionate to the severity of the crime involved -, then is it not criminality itself which is pleasurable, and the seemingly pleasure-producing act nothing more than the instrument of its realization? Virtue is not some kind of mode whose value is incontestable, it is simply a scheme of conduct, a way of getting along, which varies according to accidents of geography and climate and which, consequently, has no reality, the which alone exhibits its futility. Only what is constant is really good; what changes perpetually cannot claim that characterization: that is why they have declared that immutability belongs to the ranks of the Eternal's perfections; but virtue is completely without this quality: there is not, upon the entire globe, two races which are virtuous in the same manner; hence, virtue is not in any sense real, nor in any wise intrinsically good and in no sort deserves our reverence. Eros and reason are two very different horses hitched to the same chariot. So finally, Richard, delightful are the pleasures of the imagination! In those delectable moments, the whole world is ours; not a single creature resists us, we devastate the world, we repopulate it with new objects which, in turn, we immolate.

Other Interviews:

Herbart, Helmholtz, Heine, Rousseau, Cohen, Machiavelli, LaMettrie, Smith, Buchner, Lange, Newton, Berkeley, Hobbes, Locke, Cudworth, Hume, Leibniz, Leporin Erxleben, Fichte, Schiller, Herder, Kierkegaard, Schelling, Kant, Dilthey, Marx, Descartes, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche

About the Author

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.