The Modal Metaphysics of Lost Highway

The following is an attempt to track some of the salient elements of David Lynch’s films largely through the different but related lenses developed by contemporary philosophers Timothy Williamson and Kit Fine. I do so because I think they both offer models to understanding the films more fruitfully than competing interpretive models. Or maybe it runs the other way: I’m using David Lynch to model the modes of modality of Williamson and Fine. I guess I’m doing both. Kind of. And I end up with different conclusions depending on how far into the thing you get. One minute a film is definitely Williamsonian, the next absolutely Finean. The plot of this is as confusing as Lynch at his best, but unlike Lynch the confusion here is caused as by my own confusion rather than brilliant design. So bite me!

David Lynch’s films are often described as confusing, dreamlike, or surreal, but those descriptions miss something decisive. The confusion they generate is not simply interpretive. It is structural. Viewers do not merely wonder what a scene means. They wonder what kind of world would allow such a scene to occur at all. This is already a metaphysical question, whether it is recognised as such or not.

In most narrative cinema, the metaphysical background is stable. Characters persist through time. Events occur in a determinate order. Possibilities narrow as stories progress. Even when narratives deceive or withhold information, they do so against a fixed background of what must remain the case. Lynch disrupts that background. He constructs films in which identity can fracture without explanation, where events repeat without becoming copies, and where worlds seem to fold back on themselves rather than advance.The claim of this book is that these effects cannot be adequately understood using the usual interpretive tools. Psychological explanations treat the films as depictions of interior states. Symbolic readings turn every anomaly into metaphor. Both approaches assume that the world of the film is ontologically ordinary and that all strangeness occurs within it. Lynch’s cinema resists that assumption. The strangeness belongs to the world itself.

To understand that world, we need a theory of modality.

Timothy Williamson’s paper “Accepting a Logic, Accepting a Theory”, when reading through a collection of essays in Yale Weiss and Romina Birman’s Saul Kripke on Modal Logic early last year. It addresses issues in the philosophy of logic, particularly how one should understand the acceptance of a logic standardly conceived in analytic philosophy. Williamson takes up a challenge motivated by Kripke’s critiques of alternative logics and the broader question of whether adopting a non-classical logic is really a “change of subject” or something more like adopting a new scientific theory. Williamson’s core question is deceptively simple: what does it amount to accept a logic? And his answer is deliberately deflationary. Accepting a logic is not a sui generis philosophical act, it is the same kind of thing as accepting any other theory.

This is what later came to be labelled anti-exceptionalism about logic. He starts by targeting a deeply entrenched assumption in analytic philosophy, namely that logic is special in a way that makes it immune to ordinary epistemology. On the “exceptionalist” picture, logic is constitutive of thought itself. To reject classical logic would therefore not be to make a mistake but to change the subject. You see this idea in various forms in Quine, Carnap, and in some readings of Wittgenstein. Williamson thinks this picture is unstable. If logic is constitutive of thought, then disagreement about logic should be impossible in a very strong sense. But disagreement clearly happens, and not just verbally. Logicians argue, persuade, revise, and sometimes abandon systems. That social fact is his starting datum. His first major move is the folk theory vs scientific theory analogy. Williamson asks us to compare logic with physics. Ordinary people have inferential dispositions about motion, causation, and space. Those dispositions form something like a “folk physics”. Scientific physics does not merely describe those dispositions, it often corrects them. Yet we do not think adopting relativity means changing the meaning of “motion” or “time” in a way that makes disagreement with Newton impossible. The analogy is meant to dissolve the idea that logical revision must be conceptually incoherent. If ordinary inferential practice can be improved upon, why not logical practice as well? Crucially, Williamson does not say that logic is empirical in the same way as physics. The analogy is epistemological, not metaphysical. It concerns how we justify acceptance, not what the subject matter is.

This sets up his second key distinction: logic vs metalogic. Many arguments for the special status of logic rely on results about logical systems, for example soundness, completeness, consistency proofs. But those are metalogical results, typically carried out using background mathematics and often classical reasoning. Williamson insists that using classical metalogic to study non-classical logics is not circular in a vicious sense. It is no worse than using current physics to evaluate rival physical theories. Acceptance happens at the object level, not at the level of the tools used to evaluate candidates. This blocks a common objection that you cannot rationally argue for a logic without presupposing it. Williamson’s reply is that presupposition in practice does not entail incorrigibility in principle. The most subtle part of the paper concerns inferential dispositions.

Williamson denies that accepting a logic consists in explicitly believing axioms or rules. Instead, acceptance consists in having defeasible dispositions to infer in certain ways. By calling dispositions defeasible philosophers just mean that they are not exceptionless. They can be overridden, trained, refined, and sometimes corrected. This is crucial for explaining how rational disagreement about logic is possible. If logic were a set of explicit meanings fixed by stipulation, disagreement would collapse into verbal dispute. But if logic is embodied in fallible cognitive practices, then disagreement can be substantive. This is where Williamson shifts the debate from semantics to epistemology. The question is no longer “what do logical constants mean?” but “what inferential practices should we endorse, and why?”

At this point he turns explicitly to the Quinean ‘change of subject’ objection. The objection says: when a classical logician and an intuitionist disagree about excluded middle, they are not really disagreeing, because “not” and “or” mean different things for them. Williamson’s reply borrows heavily from Kripkean externalism. He invokes the general idea, familiar from Saul Kripke and Hilary Putnam, that meaning is not fixed by what is “in the head” of individual speakers. Meaning is anchored in communal practice, deference, and causal history. Just as chemists can disagree about whether water is H₂O without changing the subject, logicians can disagree about valid inference without talking past one another. Disagreement does not require perfect semantic alignment, only enough shared practice to sustain correction and critique. Thus Williamson thinks Quine’s argument overreaches. It assumes a descriptivist picture of meaning that Kripke himself undermined.

The role of Kripke is important here. Kripke famously argued that some logical laws, especially those tied to necessity, have a kind of objectivity that resists conventionalism. Williamson is sympathetic to this realism but rejects the conclusion that logic is unrevisable. Objectivity does not entail immunity from error. In effect, Williamson is offering a realism without exceptionalism. Logical facts are real, but our access to them is mediated by fallible theory, just like everywhere else. The payoff comes at the end. If accepting a logic is accepting a theory, then debates between classical, intuitionistic, relevant, or paraconsistent logics should be assessed using familiar theoretical virtues: explanatory power, simplicity, coherence with mathematics and science, fruitfulness. There is no sharp line where philosophy stops and logic begins. Logical theory choice is continuous with rational inquiry more generally. This is a radical conclusion. It undercuts both logical dogmatism and the idea that logic is merely conventional. Logic becomes a domain of responsible, corrigible judgement.

In The Philosophy of Philosophy and later in Modal Logic as Metaphysics, Williamson continues to insist that logic is not methodologically special. There is no autonomous “first philosophy” that settles logical truth prior to theory. Logic is continuous with mathematics, metaphysics, and science, and its acceptance is governed by the same epistemic norms. As I’ve just sketched, in the early paper this continuity is defended mainly at the level of epistemology. Accepting a logic is like accepting a theory because both involve defeasible inferential dispositions, sensitivity to counterexample, and communal standards of correctness. In The Philosophy of Philosophy, this gets generalised. Williamson argues that all philosophical methodology works this way, including thought experiments, modal intuitions, and conceptual analysis. What was a claim about logic becomes a claim about philosophy as such. The same is true of the anti-Quinean move. In the paper, Williamson uses Kripkean externalism to block the “change of subject” objection. In later work, especially in Modal Logic as Metaphysics, this becomes a full-blooded realism about modality.

Logical disagreement is possible because there are objective modal facts, even if our access to them is theory-mediated and fallible. The early defence of disagreement sets up the later defence of realism. Where things really harden is Williamson’s attitude toward necessity and classical logic. In the early paper, Williamson is careful not to prejudge which logic is correct. His anti-exceptionalism is officially neutral. Classical logic, intuitionistic logic, and others are all in principle revisable. What matters is how well they function as theories. By the time we get to Modal Logic as Metaphysics, that neutrality is gone. Williamson now explicitly endorses classical logic and classical modal logic as the correct framework for metaphysics.

Necessity is no longer treated as something we infer via fallible dispositions. It becomes metaphysically robust, mind-independent, and governed by S5-style principles. Ok. Its hard to avoid technical terms of art like S5 and the like in this area of philosophy. It can be off putting to non specialists but I think once you keep track of what these technical terms are doing its actually interesting. The trouble comes trying to remember what they mean each time they crop up because often the specialists forget to ensure their readers are keeping up with them and they rush on and you get lost. So throughout I’ll keep reminding readers what these terms of art mean each time so you don’t have to scramble back looking for the explanation.

So there are these S-systems, and thinking about them helps to see why S5 is powerful but also why some philosophers resist it. All of these systems are ways of regimenting how necessity and possibility behave. They differ in how “rigid” they make modal space. (Modal is just about necessity and possibility). The weakest commonly discussed system is K. K just gives you the bare minimum needed to reason with necessity and possibility at all. It says, roughly, that if a necessary rule holds, then it holds in all cases where it is applied. But K places almost no structural constraints on how possibilities relate to one another. It is very permissive and very thin. Philosophically, it corresponds to a view where modal structure is largely unspecified.

A step up is T. T adds the idea that whatever is necessary is true. This is often taken to be non negotiable once necessity is understood as “could not have been otherwise”. T already rules out some exotic views, such as necessities that somehow fail to obtain. Then comes S4. S4 adds the principle that if something is necessary, then it is necessarily necessary. This gives necessity a kind of stability. Once a fact counts as necessary, it stays necessary across all possible perspectives. Many philosophers find S4 attractive because it captures the idea that necessity does not flicker or weaken, but it still allows possibility to be more flexible.

Finally there is S5, which adds the strongest principle: if something is possible, then it is necessarily possible. This collapses many distinctions between different “levels” or “grades” of possibility. All possible worlds become mutually accessible. Modal space becomes fully symmetric and flat. You can also think of these systems in terms of how they treat access. Imagine each possible world can “see” some others. K allows almost any pattern of seeing. T says every world sees itself. S4 says if a world sees another, it also sees everything that other world sees. S5 says every world sees every other world.

Why does this matter philosophically? Because choosing one of these systems is not just a technical decision. It reflects how you think reality itself is structured. Williamson is comfortable with something very close to S5 because he thinks necessity is grounded in what things are, their identity and existence, not in perspective, language, psychology, or history. Once the world fixes what is possible, that fixity applies everywhere. (Someone like Kit Fine is much more cautious. Even though he is not hostile to modal logic, he resists the idea that one single modal operator captures all the ways in which things can be necessary. He thinks there are different kinds of necessity, grounded in essence, law, norm, practice, affect, and structure. For that reason, flattening all modality into something S5-like risks losing important distinctions. We’ll be coming to Fine later. This is just so you can see where these two diverge a bit. )

Back to Williamson for now. The early paper clears the methodological ground by saying logic could be revised. The later work says that, given our best theories, it should not be. Anti-exceptionalism survives, but it no longer motivates pluralism. Instead it legitimises realism and theoretical conservatism. You can see this clearly in how Williamson treats counterexamples (e.g. if the match had been wet then it wouldn’t have ignited). In the early paper, deviant intuitions count as data that might push us away from classical logic. In the later work, many such intuitions are reclassified as cognitive error, performance failure, or confusion about the metaphysics of necessity. The same epistemology is still in play, but the verdicts are firmer. What quietly drops out over time is the emphasis on inferential practice.

In the paper, Williamson leans heavily on inferential dispositions. Acceptance of logic is grounded in how agents reason, how they are trained, and how they revise their habits. This gives the paper a faintly sociological or pragmatic flavour, even though Williamson is not a pragmatist. In Modal Logic as Metaphysics, this dimension recedes. The focus shifts from practice to structure. Logical systems are evaluated less by how they regulate reasoning and more by how well they capture objective modal reality. The metaphysics does the heavy lifting. Inferential dispositions become evidence rather than constitutive elements. This shift matters philosophically. The early Williamson leaves space for a kind of fallibilist modesty about logic, even if he is not a pluralist. The later Williamson is far more confident that we already have the right tools. Critics often say that anti-exceptionalism ends up functioning as a ladder that is kicked away once classical modal logic is safely installed.

Seen this way, the paper is best understood as transitional. It dismantles the idea that logic is beyond theory choice, but it does not yet assert a strong metaphysical picture of necessity. Modal Logic as Metaphysics supplies that picture and then uses it to justify a fairly orthodox logical framework. One way of putting it is this: early Williamson is trying to make logical disagreement intelligible; later Williamson is trying to explain why most of it is mistaken. Williamson’s opening move in Modal Logic as Metaphysics is to take something that looks, at first glance, like an abstract piece of logical machinery and put it under metaphysical pressure.

He begins from an ordinary thought: things could have been otherwise. A coin you are holding could have landed tails rather than heads. A tree that exists might never have grown. And it can seem just as obvious that what things there are could have been otherwise too: perhaps there might have been fewer things, or more things, or even nothing at all. Williamson starts by letting that intuitive picture speak in its most natural voice: the universe could have evolved differently so that there was never any money, and in that case there would not merely have been no coins, there would have been no such particular coin at all, because it simply would not have been. Conversely, there could have been something that is actually nothing, like a coin design never minted. So, he says, there is something that could have been nothing, and something that could have been something.

That is the intuitive entry point for a dispute about whether “what there is” is contingent. But he immediately brings into view a rival tradition. Some philosophers, he notes, have denied that it is contingent what there is, while allowing that it is contingent how what there is is arranged or behaves. The pieces are fixed, only the pattern changes. He uses Wittgenstein’s Tractatus as a salient representative of the idea that there is an “unalterable form” of objects, with variability located in their configuration rather than in the inventory itself. Williamson is careful not to get bogged down in exegesis, and he signals that the real aim is not about Wittgenstein in particular, but about a view: that it is necessary what there is.

At this point he introduces two names that become organising labels for the whole book. Call the proposition that it is necessary what there is “necessitism”, and its negation “contingentism”. So either “Ontology is necessary” or “Ontology is contingent”. ('Ontology' just means what exists. If you say that Yuxin exists, you’re doing ontology.) But Williamson is also explicit that these are not yet detailed theories. They are high altitude generalisations that can be combined with many auxiliary assumptions, and neither side by itself settles particular case questions like whether there are animals, or which animals there are, or whether numbers exist.

The disagreement is about the general claim that necessarily everything is necessarily something. Note that the necessity at issue is metaphysical, not epistemic. Williamson insists that the question is not what can be known, thought, or said, but what could not have been otherwise, in the relevant metaphysical sense. This is important because many people hear “necessary” and slide into “knowable a priori” or “analytic”. Williamson is trying to keep those debates at arm’s length. He is also explicit that the dispute is not immediately about “laws of physics” or about science fiction scenarios. You can be a necessitist while denying that the laws of nature are metaphysically necessary. You can allow that the laws might have been different, while still maintaining that the inventory of “somethings” is fixed.

Conversely, you can be a contingentist while granting that some items, like numbers on a Platonist view, are non contingent. The core issue is about the general, unrestricted claim, not about whether there are special necessary beings. Williamson refuses to let the debate stay at the level of vibe. If necessitism sounds crazy, that is not yet an argument. If contingentism sounds like common sense, that is not yet decisive either.

The first chapter is an exercise in making the debate precise enough that later logical machinery can actually bite. One way he does this is by pairing the modal dispute with a temporal analogue. If necessitism says “it is necessary what there is”, a temporal cousin would say “it is always the case what there is”. That temporal thesis is what he calls permanentism, and its negation temporaryism. The point is use a structural analogy: both debates involve quantifying “always” or “necessarily” over “everything”, and both invite similar confusions about what is being held fixed. Williamson suggests that a lot of resistance to necessitism comes from conflating it with claims that would be better classified as permanentist, or with muddled combinations of modal and temporal readings. The pairing also helps him later, because temporal logic and modal logic share formal patterns.

From there he asks : why take necessitism seriously at all? Surely it is obvious that many things could have failed to exist. Williamson’s distinguishes the attitude “it seems obvious, therefore it must be false” from the attitude “it seems obvious, therefore any argument for the opposite must be fallacious”. He complains that the latter attitude can deadlock inquiry. If we treat every contrarian hypothesis as equally serious, we get swamped by blogger level proliferation. If we refuse to treat any contrarian hypothesis as serious because it offends the obvious, we risk missing cases where the obvious turns out to be wrong. So we need some principled way to decide which hypotheses are worth real theoretical attention.

That is already a preview of his broader posture: treat logic and metaphysics as parts of theoretical inquiry, to be assessed by something like the standards we use in other theoretical domains. But before he gets there explicitly, he runs a series of “forms of necessitism” thought experiments that show how quickly naive objections misfire. Consider a coin again, now understood as a macroscopic object made of microscopic parts. Williamson sketches two very different atomist manoeuvres a necessitist might try.

An eliminativist says, strictly speaking there is no coin, only atoms. Coin talk is a convenient shorthand for complicated talk about atoms. If so, then the coin is not a counterexample to necessitism because there is no such object as the coin. A reductionist says, by contrast, that there really is a coin, namely the mereological sum of its atoms. (Mereology is just about the relation of wholes to parts and vice versa). But then, given how the atoms change over time, the reductionist starts to look committed to saying that the coin in your pocket is never strictly the same coin from moment to moment, because the exact sum differs as atoms are gained or lost.

Williamson thinks neither defence is attractive as a way of making necessitism plausible, and the deeper point is that simply appealing to microphysics does not explain away the appearance that there could have been fewer things. Even if physics told us that the number of atoms is fixed, why could there not have been more atoms, or fewer atoms, under different laws? (Fine thinks anyone saying that coin talk is strictly speaking false because of physics is just wrong; there is no good reason to think people are making a mistake when they do coin talk and that linguistic data is important and decisive.)

Then Williamson introduces what becomes one of his recurring ontological distinctions: concrete versus non concrete. He uses “concrete” informally, as roughly “located in space and time, causally engaged, physical-ish. The key idea is that a necessitist does not have to say the coin is necessarily a coin, or necessarily concrete. The necessitist can say: necessarily, the coin is something, but it might have been non concrete, in which case it would not have been a coin. That is, contingency migrates from “whether it exists” to “whether it is concrete”. Williamson’s early chapters are an extended attempt to make that migration intelligible rather than merely verbal.

A natural reaction is to say: if it is non concrete, is it an abstract object, like a number? Williamson blocks that move. “Non concrete” is not automatically “abstract” in a positive sense, because “abstract” is not merely “not concrete”. “Abstract” has its own paradigms, like numbers and directions, tied to theoretical roles. If the coin had not been concrete, it would not thereby have played the role of a number. Williamson uses a temporal analogy to make the point vivid: when an iceberg melts, it does not become abstract, it simply ceases to be concrete. The contrast is meant to create conceptual space for entities that are neither concrete nor abstract in the familiar platonist way, which is exactly the sort of thing necessitism will later need.

Here he starts to sound like he is inventing a new category of being. He does not deny that. He calls it a cost. He also notes a familiar pattern from mathematics: set theory often posits huge infinities of sets, not because common sense wants them, but because theoretical principles that do serious work seem to require them, and the alternative can be massive loss of simplicity and elegance. This analogy is meant to loosen the grip of “but that sounds ontologically extravagant” as an immediate refutation. The question is whether the theoretical pay off warrants the ontological cost.

Williamson pivots to the ambiguity of phrases like “possible F”. The phrase “a possible president” can mean at least two things. On one reading, it is predicative: “Trump is a possible president” means Trump is a president and Trump could have existed. That is boring, and it makes “possible” function like “existing in some possible world” tacked onto existence. On another reading, it is attributive: “Trump is a possible president” means Trump could have been a president. That reading does not require Trump to be a president, or even to exist, in the actual circumstances. It is structurally like “alleged diamond”, which does not entail “diamond”. Williamson argues that the attributive reading is the one relevant to necessitist talk of merely possible objects. When you say “we are all possible murderers”, you ordinarily mean each of us could have been a murderer, not that each of us is a murderer who could have existed.

Contingentists often hear “possible object” in a way that makes it sound like Meinong’s notorious “non existent objects” with impossible properties. Williamson wants to disarm that association. He says: the necessitist’s “merely possible F” is naturally understood on the attributive reading: something that could have been an F but is not an F. On this reading, “merely possible stick” is coherent: it could have been a stick, but is not a stick. The point is not that we can picture such a thing, but that the grammar of modal attribution already supports the idea that possibility can attach to predicates, not merely to existence. In Lynch’s Twin Peaks there’s the Black Lodge where the idea that someone could have been a tree but isn’t a tree is illustrated by depicting the person who could have been a tree as a tree even though he isn’t and couldn’t have been. Well now.

Williamson then introduces what looks like a metaphysical challenge: “Where is the merely possible coin, actually?” The answer is: nowhere. In Lynch’s Twin Peaks the same answer is: In the Black Lodge. But Williamson argues that this is not decisive, because the analogous temporal question also has a “nowhere” answer. Where is the past coin now? Nowhere. That does not show that past objects are incoherent, or in the Black Lodge. It shows that location talk can mislead when applied outside the concrete present. This is part of a broader strategy in the early chapters: use temporal cases, which many people are already willing to treat seriously, to make modal cases less alien.

A further challenge says: modal properties must be grounded in non modal properties. A lump of clay is malleable because of its microstructure, and the microstructure is non modal. So, if an object is merely possible and has no concrete microstructure, how can it have modal properties like “could have been a stick”? Williamson pushes back by questioning whether the modal versus non modal distinction is even clear in the way that objection presupposes. Microstructure has consequences for what the object can do, so why is it “non modal”? If “non modal” just means “lacking explicit modal vocabulary”, that is not a serious metaphysical distinction. The upshot is not that grounding is impossible, but that we cannot assume a simple “modal grounded in non modal” picture to rule out necessitism by fiat.

One of the most important clarifications for the whole book arrives in section 1.4: unrestricted generality. Williamson says that in the core statement of necessitism the quantifiers “everything” and “something” are absolutely universal, with no tacit contextual restriction. People often soften the claim by restricting “everything” to “everything concrete”, or “everything that exists in space and time”, and then they say “of course everything is necessarily something” because they have built existence into the domain. Williamson’s point is that the interesting dispute only begins when both sides are quantifying without restriction. In ordinary conversation we often do restrict quantifiers. “Everything is wet” might mean “everything in the laundry basket is wet”.

But when we are doing metaphysics of being, Williamson wants the wide open reading. This immediately resonates with Lynch’s universe which so often refuses contextual restrictors on quantifiers. This leads to an objection many logicians will recognise: unrestricted quantification is entangled with set theoretic paradoxes, because if you quantify over absolutely everything you are tempted to treat “everything” as forming a set, and then Russell style contradictions loom. (ie is the set of all sets in itself?) Williamson’s argues against this by saying that unrestricted quantification does not by itself generate contradictions. Contradictions arise only with auxiliary assumptions, like that the things quantified over form a set. We can reject those auxiliary assumptions without rejecting unrestricted quantification. He treats unrestricted quantifiers as intelligible.

Necessitism starts looking like a consequence of taking certain logics of modality with unrestricted quantification and identity seriously. Contingentism looks like the attempt to keep the logic while blocking the metaphysical consequence, typically by complicating either the logic (special rules, restricted inference) or the semantics (variable domains, free logic). Williamson is preparing the ground so that when the technical results arrive, the reader cannot escape by saying “oh, you just meant ‘exists’ in the restricted sense anyway”.

Some philosophers, especially David Lewis, treat modal operators like “possibly” and “necessarily” as quantifiers over possible worlds, understood as maximal concrete spatiotemporal systems, big, concrete realities like our own, just causally isolated from us. On this view, when you say “possibly P”, what you really mean is “there is some possible world in which P is true”. So take a simple sentence. “There could have been no donkeys.” On the Lewisian picture, this is true because there is a possible world which is just like ours in many respects but where evolution went differently and no donkeys ever existed. The sentence is true because one of the worlds has no donkeys. So far, this seems intuitive and harmless. Now bring in quantification, words like “everything”, “something”, and “nothing”. Lewis and many other metaphysicians often use unrestricted quantification. That means when they say “everything”, they really mean everything there is, not just everything in some domain like “everything in this room” or “everything in this world”.

This is where the trouble begins. Consider the necessitist claim Williamson wants to make precise: “Necessarily, everything is necessarily something.” In plain terms, this says: anything that exists exists necessarily. Nothing winks in and out of existence across possible worlds. Now translate that into Lewis’s framework. “Necessarily P” means “in every possible world, P is true”. So the necessitist sentence becomes something like: “In every possible world, everything is necessarily something.” But now ask: what does “everything” range over? If quantification is unrestricted, then “everything” already ranges over all objects across all possible worlds. Not just the objects in one world, but all objects full stop. If that is how the quantifier works, then the sentence starts to collapse. Why? Because if “everything” already includes all objects, then saying “everything is something” is just a logical truism. Of course everything is something. Otherwise it would be nothing, and then it would not be included under “everything”. So when you combine these two moves treating necessity as quantification over worlds and treating object quantifiers as unrestricted you risk turning the deep metaphysical claim of necessitism into something like: “In every world, everything is something.” Which is as empty as saying: “Everything exists.” That is not a substantive thesis about modality or existence. It is just a logical truth.

To see this more concretely, imagine a toy universe of objects. Suppose your ontology includes Alice, Bob, and a unicorn that exists only in a possible world W2. If your quantifier “everything” ranges over Alice, Bob, and the unicorn regardless of world, then saying: “Everything exists in every world” cannot mean what the necessitist wants. Because the unicorn does not exist in the actual world in the Lewisian sense. So either the statement is false in an uninteresting way, or you quietly shift the meaning of “exists” so that “exists” just means “is in the unrestricted domain”. Either way, the claim loses its intended force. Williamson doesn’t argue that Lewis’s modal realism is incoherent or false. He says that using modal realism as the framework for debating necessitism versus contingentism distorts the issue. If necessity just means “true at all worlds”, and existence is already handled by an unrestricted quantifier, then modal claims about existence stop doing real work. They become artifacts of how we set up the semantics, not discoveries about reality.

That is why Williamson insists that the debate should not be conducted in a framework that reduces modality to quantification over concrete worlds. He wants a framework where necessity is a genuine metaphysical notion, not a by product of how we count worlds. If you treat modal operators as nothing more than world quantifiers, and you treat object quantifiers as unrestricted, then deep metaphysical disputes about existence risk being flattened into trivialities. To preserve the substance of the necessitism debate, you need a conception of modality that is not simply world counting. Another potential confusion he targets is the “actualism versus possibilism” terminology in the literature. In ordinary language, “actually” often sounds weighty. It seems to point to what really exists, as opposed to what merely could have existed.

Because of this, philosophers introduced a contrast between actualism and possibilism, thinking they were marking a deep metaphysical divide. The usual gloss goes like this. The actualist says that everything that exists is actual, and there are no merely possible objects. The possibilist says that there are things that are possible but not actual, like possible people or possible worlds. Williamson says that once you look carefully at how the word “actually” behaves in modal logic, that way of framing the dispute collapses.

In modal logic, “actually” is treated as an indexical operator. It works a bit like “here” or “now”. Saying “actually P” just means “P is true at the actual world”. Crucially, unless it appears inside another modal context, it does not change the truth value of what you say. So take the sentence: “Everything that exists actually exists.” Under the modal logic reading, this becomes trivial. It is like saying: “Everything that exists exists here.” That cannot possibly be false. Whatever exists, exists where we are evaluating existence from. Nothing metaphysical is being said. Here is a simple example. Imagine you say: “There are dinosaurs.” That is false. But if you say: “There are actually dinosaurs,” it is still false. Now imagine you say: “There are mammals.” That is true. And if you say “There are actually mammals,” it is still true. Outside of special modal contexts, “actually” does no work. It does not add metaphysical depth.

Now consider a sentence where “actually” does matter. “It is possible that there are flying pigs.” That sentence is true in a loose sense. But now say: “It is possible that there are actually flying pigs.” This second sentence is false, because it says there is a possible scenario in which, at the actual world, there are flying pigs. That is not the case. Here “actually” matters because it sits inside a modal operator. Williamson’s point is that if the actualist versus possibilist debate is framed using “actually” in the trivial sense, then the dispute reduces to something empty. Of course everything that exists actually exists. That is not a metaphysical thesis, it is a logical truism.

So if philosophers really want to argue about what exists, they must mean something else by “actual”. But once they introduce a heavier, metaphysically loaded notion of actuality, the terminology becomes unstable and unclear. Different authors mean different things, and arguments slide past one another. This is why Williamson thinks the language of actualism and possibilism has become hopelessly muddled. It mixes a harmless logical operator with a much stronger metaphysical idea, without clearly separating them.

The real issue, he says, is not whether everything is actual, but whether everything that exists exists necessarily. That is the dispute between necessitism and contingentism. The necessitist says: everything exists in every possible world, though it may have different properties in different worlds. The contingentist says: some things exist in some worlds but not others. That disagreement is genuinely metaphysical, clearly stated, and not hostage to the ambiguities of the word “actually”.

So the upshot is that Williamson is not denying that there are deep questions about existence and modality. He is saying that the traditional actualism versus possibilism labels obscure those questions rather than clarifying them. By switching to necessitism versus contingentism, the debate becomes precise enough to do real metaphysical work. Similarly, in the philosophy of time, “presentism versus eternalism” is often glossed as “everything is present” versus “not everything is present”. Williamson runs an analogous complaint: on the straightforward temporal logic reading of “presently”, “whatever is, presently is” is trivial. So again the interesting metaphysical dispute should be reformulated as permanentism versus temporaryism, which targets the claim that “always everything is always something” rather than a linguistically unstable “present” predicate.

Williamson wants logic and metaphysics to be assessed together. He discusses the necessity of identity and distinctness. In standard modal logic with identity, if x is identical with y, then necessarily x is identical with y. Likewise, if x is distinct from y, then necessarily x is distinct from y, given some plausible background principles. He sketches arguments for these claims and says that, in natural models, they come out valid. You can always tinker with identity interpretation to make them fail, but you can do that for any argument, and it would be bad methodological taste to uglify a strong, elegant logic of identity just to avoid ontological inflation.

The book’s central method is to start with a powerful logic, then treat metaphysical conclusions that fall out of it as serious candidates, unless there is overwhelming reason to distort the logic. This is a clue to Williamson’s ambition: modal metaphysics is a structural picture of objects across counterfactual and temporal variation. He then begins the process of showing how the metaphysics is “intimately connected with some technical issues” in quantified modal logic, especially the Barcan formula and its converse.

Quantified modal logic is just first order logic (with “for all” and “there exists”) plus modal operators (usually “necessarily” and “possibly”). It inherits the familiar truth functional connectives like “and”, “or”, “not”, “if…then”, and adds modal operators that shift evaluation across possibilities. Williamson defines this as a combination of the two logics, plus new problems about their interaction. The Barcan formula, in one common modern notation, says roughly: if it is possible that there exists an x such that A(x), then there exists an x such that it is possible that A(x). In symbols, ◇∃x A → ∃x ◇A. Intuitively, it moves an existence claim out of the scope of “possibly”. The converse Barcan formula goes the other way: if there exists an x such that possibly A(x), then possibly there exists an x such that A(x).

The philosophical anxiety is that the Barcan formula seems to imply that whenever it is possible that something of a certain kind exists, there is already something, actually, that could have been that kind of thing. That sounds like it commits you to “mere possibilia” as actual entities. On Williamson’s picture, that is not a bug but a feature, because it is closely allied to necessitism.

Williamson explains that the Barcan formula emerged in a technical, even austere, setting in the mid twentieth century. He traces it to Ruth Barcan Marcus’s 1946 work on a formal system of quantified modal logic built on C I Lewis and Langford’s strict implication framework. In that setting the work is “syntactic”: it lays down axioms and rules, proves theorems, and does not supply a semantics or even an informal English reading. The symbols are intended to function as quantifier and possibility operators, but the metaphysical significance is not argued for. This historical point matters to Williamson because he is trying to dissolve the idea that logic and metaphysics are disjoint, and that therefore theorems of a formal system cannot have metaphysical consequences. If logic is “good” and metaphysics “bad”, then “no logic is metaphysics”, and you can treat the Barcan formula (roughly: whenever it is possible that something of a certain kind exists, there is already something, actually, that could have been that kind of thing) as a harmless formal convenience.

Williamson thinks that posture became harder to maintain, precisely because once we start using quantified modal logic to represent metaphysical claims about necessity, possibility, and existence, the boundary becomes porous. The early history of the Barcan formula is, for him, a case study in how technical results acquire metaphysical weight once we begin interpreting them in the relevant ways. At first the Barcan principles are adopted in a setting where semantics is suppressed, then later, as semantics and intended interpretations develop, the principles begin to look “metaphysically problematic”, and contingentists try to avoid them. Those attempts, he hints, often “come to grief”, pushing contingentists toward significant restrictions in their logic. He aims to show “how early contingentist attempts to avoid them came to grief” and why later attempts paid a high price.

The Barcan formula (roughly: whenever it is possible that something of a certain kind exists, there is already something, actually, that could have been that kind of thing) is not just a random axiom. In many semantic treatments, it corresponds to a structural assumption about domains of quantification across possible worlds. Roughly, if the domain is constant across worlds, then moving ∃x out of ◇ is safe, because the things you quantify over do not vary from world to world. If the domain varies, then the move can fail, because something might exist in one world but not be among the things quantified over in another. This is how he will connect logical principles to metaphysical theses.

Suppose you think Wittgenstein could have had a child. Contingentism, in its intuitive form, says: there is a possible world where Wittgenstein has a child, and in that world there is an individual who is his child, but in the actual world there is no such individual at all, because Wittgenstein in fact had no children. The Barcan formula, read naively, seems to say: if it is possible that Wittgenstein has a child, then there exists, actually, something that could have been Wittgenstein’s child. That “something” is not any actual person, because there is no such person. So it looks like you have to accept some merely possible individual as an inhabitant of your actual ontology.

Ted Sider, summarising Williamson’s position, puts it starkly: “if there could have been a child of Wittgenstein, then there in fact exists something that could have been a child of Wittgenstein”, and this thing is “nonconcrete”, a “bare possibilium”. Notice how that connects directly back to Williamson’s insistence that “non concrete” need not mean “abstract like a number”. The child of Wittgenstein that could have been is not, on Williamson’s view, a concrete human being with mass and location. It is something that could have been concrete, but is not.

If you accept that kind of entity, the Barcan formula starts to look like a natural logical reflection of it, rather than a metaphysical horror. Of course in Lynch it does look like metaphysical horror too.

At this point the dispute becomes methodological. The contingentist can respond by rejecting the Barcan formula (roughly: whenever it is possible that something of a certain kind exists, there is already something, actually, that could have been that kind of thing), or by changing the logic so that the inference patterns that lead to it are blocked. But Williamson’s project, as both his own framing and sympathetic summaries emphasise, is to argue that the “best” modal logic, judged by a mixture of simplicity, strength, and theoretical utility, includes principles that entail the Barcan schema and thereby support necessitism.

Sider’s reconstruction of Williamson’s strategy is especially helpful for understanding that Williamson is not trying to derive necessitism from “pure reason” alone. He is arguing that when you adopt the classical rules of inference for modal logic, and you do not impose ad hoc restrictions motivated only by the desire to save contingentism, you get a logic that carries with it necessitist commitments. Contingentists then have to decide where to resist: perhaps by restricting existential generalisation, adopting a free logic, restricting necessitation, or adopting variable domain semantics with special truth conditions. Each resistance tends to come with a cost in complexity, loss of elegance, or loss of inferential power.

Williamson’s wager is that those costs are not worth paying, so the theoretically preferable package is the strong logic plus necessitist metaphysics. Williamson’s “Possible Worlds Model Theory”, connects the metaphysical issues to possible worlds model theory, understood as a mathematical framework used in formal semantics, and he calls it the “main technical achievement of modal logic”. His deeper ambition is to explain how to read systems of modal logic as metaphysical theories, so that the model theory can be applied to metaphysics rather than treated as a merely linguistic tool.

That is exactly the bridge Williamson needs if the Barcan formula is to be more than a theorem inside a calculus. If the model theory is read as representing the structure of metaphysical modality, then constraints like constant domains are not arbitrary modelling choices, they are metaphysical commitments. Conversely, if you refuse that reading, then the model theory cannot straightforwardly tell you what metaphysics to accept.

A basic picture of possible worlds model theory, in the minimal Kripkean sense, goes like this. You have a set of “worlds” (often understood abstractly, not necessarily Lewisian concrete universes), an “accessibility relation” that says which worlds are relevantly possible relative to which others, and a valuation that assigns truth conditions to sentences at each world. For quantified modal logic, you also need domains of individuals at each world. If the domain is constant, you quantify over the same individuals at every world. If it is variable, the domain can expand or contract from world to world.

In the simplest models of constant domain semantics with identity, the Barcan formula and its converse typically come out valid, and in that setting necessitism looks like the natural metaphysical interpretation: everything is something in every world, though it may be concrete in some worlds and non concrete in others. In variable domain models, you can invalidate the Barcan formula, and that seems to match contingentism’s intuition that some individuals “do not exist” in some worlds.

So then we can ask: what justifies choosing the more complex variable domain machinery? Is it independently motivated, or is it a patch built solely to block a metaphysical consequence we find uncomfortable? Sider points out that the variable domain approach faces a formal challenge of assigning truth values to statements in worlds where objects denoted in the statement do not exist, and a philosophical challenge of explaining how such models can be “intended” if possibility and necessity are not reducible to facts about worlds and their inhabitants, which many contingentists also agree on.

Williamson’s point is that, once you stop treating possible worlds as metaphysically basic concrete realms, you lose the easy story that makes variable domains look like “obvious metaphysics”, and the semantics starts to look like a technical workaround whose metaphysical interpretation is unstable. What is distinctive in Williamson’s approach is that he treats these choices as theory choices. He explicitly says, in the context of identity, that we should be guided by a conception of theories in logic and metaphysics as scientific theories, to be assessed by the same overall standards as theories elsewhere, including mathematics. That is a striking claim because it insists on theoretical virtues like simplicity, power, and integration.

And it is meant to reverse a familiar order of deference. Many philosophers think we should first settle metaphysics by intuition or conceptual analysis and then choose a logic that fits. Williamson wants to treat the logic itself as part of our best theorising about structure, and then adjust metaphysics to fit the best logic, unless there is a compelling reason not to. Keeping that methodological stance in view Williamson can be read as building a sequence of pressures. The first pressure is conceptual: once you insist on unrestricted quantification, the simple statement “necessarily everything is necessarily something” cannot be defused by ordinary contextual restriction tricks. That forces contingentists to say something substantive about what the quantifiers range over and how “is” and “exists” function in their framework. Williamson even recommends avoiding “exists” as a key term because it carries misleading restricted readings, preferring to formulate the theses with “something” and “everything” instead.

The second pressure is linguistic: the ambiguity of “possible F” and related constructions shows that our ordinary modal talk already supports attributive readings on which something can “be a possible F” without being an F, which opens the door to merely possible objects understood as could have been Fs. This does not prove their existence, but it undermines the complaint that such talk is grammatically incoherent or necessarily Meinongian.

The third pressure is logical: classical modal logic with identity delivers strong principles like the necessity of identity and distinctness. Williamson argues it would be perverse to distort that logic just to avoid the ontological consequences that arise when you combine it with modal claims about what could have been. Better, he suggests, to accept the ontological inflation and then ask whether it is theoretically harmless, in the way that large infinities can be theoretically harmless or even theoretically required in mathematics.

The fourth pressure is historical and interpretive: the Barcan formula (roughly: whenever it is possible that something of a certain kind exists, there is already something, actually, that could have been that kind of thing) and its converse emerged in a setting where semantics was suppressed, but as soon as we start using quantified modal logic to express metaphysical claims, we cannot pretend that theorems are metaphysically inert. The history is meant to show that the logic did not begin life as a metaphysical doctrine, but also that it became one once the boundary between logic and metaphysics started to dissolve.

And the fifth pressure is methodological: if modal logic provides a structural core for metaphysics, then we should prefer the best modal logic by theoretical virtues, even if it forces us toward radical metaphysical conclusions. That’s Williamson’s ambition: metaphysical issues concerning necessity and possibility should be investigated by means of formal logic, and the best modal logic is a strong higher order S5 with classical rules, with necessitism as “part and parcel” of that logic, while alternatives “fare less well”.

It is worth lingering on what “S5” and “higher order” mean here, without drowning in notation. S5 is a standard system of modal logic characterised, in semantic terms, by an accessibility relation that is an equivalence relation (roughly: every world is accessible from every world in the relevant sense). Philosophically, S5 often corresponds to a strong view about modality where if something is possibly necessary then it is necessary, and if something is possibly possible then it is possible. Williamson’s broader project will not be simply to assume S5, but to argue for strong modal principles as part of the best theory. “Higher order” means that the logic quantifies not only over individuals (first order) but also over properties or relations (second order), or even higher. This matters because once you allow quantification over properties, you get powerful comprehension principles, and those interact with modality in ways that generate further necessitist pressures.

Williamson repeatedly diagnoses confusion as coming from bad formulations and unstable terminology. “Actualism versus possibilism” is muddled because “actual” is ambiguous between a rigid operator in modal logic and a metaphysical notion of being actual that would do harder work. “Presentism versus eternalism” is similarly muddled because “present” slides between a temporal indexical operator and a metaphysical thesis about what exists. Even “exists” is misleading because it invites restricted readings that trivialise the claims. The point is that if you are going to let logic guide metaphysics, you need your metaphysical theses to be expressible in the language the logic actually handles. Otherwise, you cannot tell whether the logic supports or undermines the thesis.

So by now we have learned that necessitism, formulated with unrestricted quantifiers, is not the childish claim that every ordinary concrete thing must exist no matter what, but a more radical and more subtle claim: the domain of “somethings” is fixed across modal space, while concreteness and other substantial features can vary. The thing that makes that plausible is not an intuition about what exists, but a willingness to accept that the best overall theory might postulate many non concrete entities as the values of unrestricted quantifiers.

We have learned that much resistance to necessitism comes from hearing it through the wrong lenses: through modal realism, which trivialises the intended claim by turning necessity into world quantification; through “actualism” talk, which often relies on an unanalysed “actual”; through “exists” talk, which slides between restricted and unrestricted readings; or through a Meinongian caricature of possible objects.

We have learned that the Barcan formula is the technical hinge where metaphysics and logic grip each other. It looks, on its face, like a theorem about the scope interaction of “possibly” and “there exists”. But once you interpret it under unrestricted quantification, it begins to look like a metaphysical statement: possibilities about existence require actual items that could have realised those possibilities. Williamson’s historical story is designed to show how that hinge was manufactured in technical work before it was understood as metaphysically loaded, and then how it became loaded as the field’s ambitions shifted. And we have learned Williamson’s guiding evaluative norm: do not sabotage a strong, simple, elegant logic to save a metaphysical prejudice. If the best modal logic, judged by theoretical virtues, implies necessitism, then necessitism deserves to be treated as a serious candidate, and the contingentist must show that the costs of necessitism are worse than the costs of complicating the logic to block it.

Consider Williamson’s knife factory style scenario. Imagine a machine that assembles knives from blades and handles. In the actual run, blade B is paired with handle H to make knife K. But if a belt had been delayed by a second, B would have been paired with a different handle H*, producing a distinct knife that never in fact exists in space and time. Williamson suggests that we can nevertheless uniquely describe “the possible knife that would have been assembled from blade B and handle H* had the belt been delayed by one second”.

A contingentist wants to say there simply is no such knife, since it was never assembled. A necessitist can say: there is such a thing, but it is non concrete. It is a possible knife on the attributive reading: something that could have been a knife but is not actually a knife. The Barcan style pressure then appears: if it was possible that such a knife existed, then there exists something that could have been that knife. Once you stop restricting quantifiers to the concrete, and once you allow “possible F” to function attributively, the necessitist package starts to look logically natural, even if ontologically extravagant.

That is why Williamson calls his book Modal Logic as Metaphysics. He is constructing the idea that modal logic is building a framework for stating, comparing, and adjudicating metaphysical theories about the structure of being across possibility and time especially through the detailed development of the Barcan principles, the assessment of competing quantified modal logics, and the higher order arguments that make necessitism harder to avoid without paying heavy theoretical costs.

Chapter 3: Modal Logic and Lost Highway

What I want to do now is apply all this to the film world of David Lynch. Modal Logic as Metaphysics insists that modal logic is not merely a convenient formal language for talking about metaphysical possibility and necessity, it is one of the main places where metaphysics itself gets done. He means that when we try to say, with any precision, what could have been the case, what must be the case, what could not be the case, and what exists across those modal claims, we very quickly commit ourselves to structural principles. Those principles are substantive metaphysical commitments.

Lynch’s Lost Highway is unusually apt. Lynch gives you a world in which identity, time, and the boundaries of what is really happening are never simply presented, they are governed by an underlying structure that you infer by watching what can and cannot happen in the narrative. The film is a machine that constrains what interpretations remain live.

That is close to Williamson’s sense that modal logic is not an optional overlay on metaphysics, it is part of the engine that generates what a metaphysical view can even be. To set up the stakes, it helps to say what “modal logic” is, for a non specialist, without flattening it. The basic modal operators are usually written as a box and a diamond. Read the box as “necessarily” and the diamond as “possibly”.

So, if P is a statement, then “necessarily P” says that P could not have failed to be true, while “possibly P” says that P could have been true, even if it is not actually true. In ordinary English, you already use these constantly. “It could have rained today” or “You could have died yesterday” are possibility claims. “Two plus two must be four” is a necessity claim. Metaphysics becomes involved when the “must” and “could” are not merely about what someone knows, or about what the laws of physics allow, but about what reality itself permits, even in principle. That is what philosophers tend to mean by metaphysical modality.

Now add quantifiers, words like “everything” and “something”. In formal logic, these are ∀ and ∃, and they let you say things like “everything is such that …” or “there is something such that …”. When you combine these with necessity and possibility you get quantified modal logic, a framework for saying things like “necessarily, everything is such that …” and “possibly, there exists something such that …”.

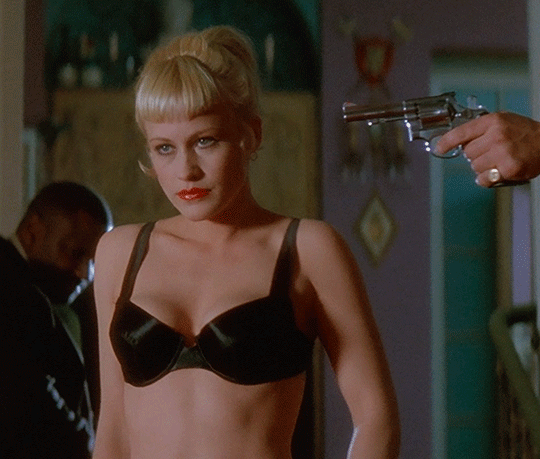

Those combinations are exactly where Williamson thinks metaphysical commitments become unavoidable, because they force you to choose how existence and modality interact. Lost Highway gives you a vivid way to feel that interaction. The film’s central unease is that the same “space of characters” seems to contain Fred Madison and Pete Dayton, and yet the film refuses to let you treat them as two straightforwardly co existing individuals within one stable story world. Fred “becomes” Pete, then later Pete “becomes” Fred, and the woman played by Patricia Arquette appears as Renee and as Alice, with the film simultaneously inviting and resisting the thought that this is one person in two guises. The narrative behaves like a model in which some individuals are present in one “region” but not another, except the regions are not physical locations, they are modal or structural positions in the story.

When the Mystery Man answers the phone and says he is at Fred’s house, the film is, in its own medium, staging something like a violation of ordinary constraints on where an individual can be at a time, and it does so by making the constraint itself the horror.

Let me just remind you of what Williamson has been doing. Williamson has put pressure on a venerable suspicion, associated especially with Quine, that quantified modal logic is somehow illegitimate or “unscientific”, “born in sin”, because it involves talk of necessity and possibility applied to quantified claims about objects. One worry is about meaning, the idea that once you talk about what is necessarily true of an object, you need a robust account of what makes it the same object across different possible scenarios.

Another worry is about existence, the thought that once you quantify inside modal operators you start committing yourself to odd things like “merely possible objects”. Williamson’s first moves are meant to show that these worries do not justify treating modal logic as metaphysically second class. He is clearing the ground for the more aggressive claim that the best metaphysics may actually be guided by the best modal logic. In other words, the logic expands what exists.

A key background assumption he flags is that metaphysics wants unrestricted quantification. That means, when you say “everything”, you mean everything, not merely everything concrete, or everything in this room, or everything actual in some narrowly chosen sense. Metaphysics, at least in the ambitious tradition, tries to speak about being as such.

Williamson wants the quantifiers in his modal logic to match that ambition. That stance matters, because many evasions of tricky modal commitments rely on quietly restricting what “there is” ranges over. In Lynch terms, it is like refusing to let the camera pan into certain corridors of the house because you know what is there will break the story. Williamson’s methodological temperament is to insist on going down the corridor.

Once you accept quantified modal logic as a legitimate arena, a famous cluster of principles shows up almost immediately. These are the Barcan Formula and its converse, usually abbreviated BF and CBF. You do not need the symbolic form to grasp the issue, but the idea is simple to state. Suppose you say, “Necessarily, everyone is such that possibly they could have been a pianist.” That is a claim where a universal quantifier appears inside a necessity claim, and then a possibility claim appears inside that.

Now compare it to, “Everyone is such that necessarily, possibly they could have been a pianist.” The Barcan type principles concern when you can move quantifiers across modal operators without changing truth. In more intuitive terms, they ask whether the domain of what your quantifiers range over stays fixed when you consider other possible ways reality might have been.

If the domain stays fixed, then whenever you talk about “everything”, you are ranging over the same stock of objects no matter which possible situation you consider. If the domain shifts, then some objects exist in one possible situation and not in another.

Lost Highway makes this feel visceral. Is “Pete” someone who exists, full stop, across the whole story world, even in the segments where he is not “there”, or is he the sort of entity that only exists within a certain narrative possibility, something like a locally generated person? The film’s unease partly depends on the fact that either answer seems to cause trouble.

If Pete exists “all along”, then Fred’s transformation is not a creation ex nihilo but some kind of identity or role shift. If Pete exists only in the “middle section”, then the story has admitted a domain shift, a new individual coming into existence in a way the film never depicts as birth, and vanishing in a way it never depicts as death.

Williamson’s central metaphysical thesis is necessitism. In one slogan form, necessitism says that necessarily everything is necessarily something. Another way to put it is that no matter how things could have been, the total domain of objects is the same. What varies across possibilities is not what exists, but which of those objects are concrete, or located in spacetime, or causally active, or in any other robust sense “present” in the world.

Necessitism is a claim about quantificational domains and the metaphysical interpretation of existence claims inside and outside modal operators. Lost Highway is obsessed with the difference between being there and being real, between appearing in the frame and being part of the story’s deep inventory. Renee is “there” in the first part, Alice is “there” in the second, but the film punishes you if you simply treat “there” as the mark of what exists.

The Mystery Man, in particular, behaves as if he is not bound by the usual conditions of presence, he can be at the house and at the party in a way that breaks ordinary individuation constraints. If you try to make sense of this by saying he is “not really real”, you are reaching for a domain restriction. But the film keeps forcing him back into the story as an operative element.

Williamson’s necessitism is the claim that what the room contains does not exhaust what there is, and that we should not read ontological conclusions off what is locally manifest. Williamson knows that many philosophers instinctively prefer contingentism, the opposing view on which what exists could have been different, in the strict sense that there might have been fewer objects or more objects.

The most emotionally compelling argument for contingentism is the common sense thought that you could have failed to exist. You were not inevitable. Surely, the contingentist says, reality could have lacked you. Williamson’s strategy is to separate several things that contingentists slide together. “You could have failed to be concrete” is not the same as “you could have failed to exist”. If we equate existence with concreteness, we are building in what we want to prove. Instead, Williamson suggests that the right metaphysical discipline is to keep the quantifier domain fixed and let properties like concreteness, spatiotemporal location, causal powers, and so on, vary across possibilities.

The choice of logical framework leads you towards a metaphysical picture. It is not merely reporting a prior metaphysical picture. An example helps. Imagine a lover you never had. Common sense says that lover does not exist. But common sense also says it could have existed. Contingentism seems to model this neatly. There is a possible world with that lover, and the actual world lacks it. Necessitism models it differently. On necessitism, there is an object which is that lover, but in the actual world it is non concrete, not located, not causally engaged, perhaps not even determinately person like in any thick sense, while in some other possible situation it is concrete and has the life you imagine.

That sounds extravagant, until you notice that contingentism also has to make room for “that lover” in some way in order to say anything informative about it. Even in ordinary discourse, you can refer to and reason about non actual individuals. Williamson’s bet is that once you systematise that practice, a fixed domain is not a gratuitous inflation, it is a way of avoiding worse confusions.

Lost Highway’s own structure is again suggestive. The film has a circular or spiral narrative structure, sometimes compared to a Möbius strip. The opening message, “Dick Laurent is dead”, appears at the beginning and is spoken again at the end, in a way that makes the story feel as if it folds back on itself. The temptation is to say that certain elements in the film only exist in certain segments. But the story’s very circularity pushes you towards another interpretation, namely that the inventory is stable while the modes of manifestation shift.

Pete is in the “domain” even when the narrative does not allow him to be concrete. Renee and Alice are in the “domain” even if they are one person under different guises, or two persons connected by some structure of projection or substitution. The film’s horror is not just that identity is unstable, but that the system that generates identity is stable and indifferent to your wishes.

At this stage you might object that the film is about psychology, not metaphysics. Lynch himself used the phrase “psychogenic fugue”, and commentators often talk about guilt and dissociation. But that distinction is exactly the kind Williamson wants you to handle carefully. The metaphysical question is not “is this psychologically motivated”, but “what structure of possibility and necessity is presupposed by the best explanation”. Williamson’s general orientation is close to a scientific realist temperament: we should treat metaphysical theorising as continuous with other theorising, guided by explanatory power, simplicity, and theoretical integration. A logic is not accepted because it flatters our intuitions. It is accepted because it helps to build the best overall theory.

That methodological note pushes his modal metaphysics towards something like a disciplined science rather than free form speculation. So Williamson’s struggle is to show you why the machinery of quantified modal logic, once you stop treating it as a purely formal game, points towards necessitism as a structurally natural position.

The alternative, contingentism, tends to require extra devices to say what you want to say without contradiction. It often involves shifting domains, plus additional principles to regulate how reference to non actual individuals works, plus story telling about how cross-world identity is fixed. Williamson’s view is that a fixed domain plus the right modal logic gives you a cleaner core. However, he spends time on what the alleged costs are. The big cost that alarms people is that necessitism seems to multiply entities, populating reality with merely possible individuals.

Lost Highway can help you distinguish multiplication from re description. The film does not, in any literal sense, add a second world on top of the first. It reconfigures how you count what is “in” the story by refusing your ordinary criteria for individuation. Once you accept that the film’s ontology is not tracked by the cast list, you can stop being spooked by the idea that there are more entities than you first thought. There were always more constraints than you recognised, and those constraints govern what you can legitimately infer.

A second cost is epistemological. Even if the domain is fixed, how do we know what exists, especially if some of it is non concrete or otherwise inaccessible? Williamson’s broader work in epistemology emphasises that knowledge is not limited to what is “given” in experience, it is the product of reliable cognitive capacities operating within a world that is not tailored to our accessibility. That outlook supports the thought that we can be entitled to modal knowledge by disciplined theorising, even if we cannot point to the merely possible like an object on a table. In Lynch terms, you cannot “see” the structure that makes the tape appear on the porch, but you can infer that there is a structure from the way events are constrained.

There is also a technical aspect that Williamson uses carefully, the distinction between semantics and metaphysics. A standard way to explain modal logic is to use possible worlds semantics, where “possibly P” means “P is true at at least one possible world”, and “necessarily P” means “P is true at all possible worlds”. This is a semantic tool, a way to model the logic.

Williamson’s insistence is that we should not mistake the semantic model for the metaphysical picture. The fact that we can represent modal talk using possible worlds does not force us into a metaphysics where worlds are concrete universes in the way David Lewis famously proposed. Williamson does not set out to refight the Lewisian battle in detail (although I’ve seen him in many videos on line where he does that), and he signals that the focus is on other structural issues. But he is clear that modal logic can be metaphysically significant even if you do not inflate worlds into vast concrete objects.

Lost Highway again is helpful. You can model the film’s structure in many ways. You could say there are two timelines, or two identities, or two narratives that interpenetrate. Those are semantic or interpretive devices. The metaphysical question, within the fiction, is what the story commits you to as real inside its own universe.

The Mystery Man might be interpreted as an external demon, a psychological projection, an embodiment of surveillance, or a personification of a camera. Each is a model. The film’s deeper commitment, though, is that whatever he is, he is not optional. The narrative rules treat him as a fixed point. Similarly, Williamson wants modal logic to give you fixed points, constraints that any adequate metaphysics must respect, even when you vary your favourite interpretations. Williamson is building a case that the right “structural core” for modal metaphysics is a quantified modal logic that is strong enough to sustain serious metaphysical generalisations, and that when you let that logic do its work it naturally favours necessitism.

Ted Sider, in engaging with Williamson, puts the thought sharply by describing quantified modal logic as supplying a central structural core to theories of modal metaphysics, even when disputing what simplicity should mean in that context. The important point for our purposes is that Williamson is trying to get you to stop thinking of these as merely technical choices. They are the metaphysical levers.

To deepen this, it helps to watch how Williamson handles the sense that contingentism is the “default”, and how he tries to flip that burden. The contingentist begins with an intuition like this: surely it is possible that nothing existed. Or at least, surely it is possible that fewer things existed. It can feel like mere stubbornness to deny that. But Williamson’s method is to push you away from raw intuition and towards disciplined constraint satisfaction. If you say “it is possible that nothing exists”, what exactly do you mean? If by “nothing exists” you mean “there are no concrete things”, then necessitism can accept that as a live possibility, depending on what further metaphysical principles you adopt. If by “nothing exists” you mean “the domain is empty”, then you are adopting an interpretation of the quantifiers that may be unfit for metaphysics, because metaphysics wants the quantifiers to be unrestricted and stable across modal variation.

You are also threatening the very logic you are using, because many inference rules presuppose non emptiness in subtle ways. Williamson’s instinct is that apparent metaphysical freedom can be purchased only by covertly weakening the conceptual tools in play. He wants to keep the tools sharp.

Think again of Lost Highway. People often say, after the first viewing, that the middle section “is not real”, or that it “never happened”, as if the film contains a segment that is simply absent from the story’s ontology. That is the analogue of the empty domain move. It feels liberating. It lets you keep your ordinary assumptions intact. But it does not respect the constraints the film itself imposes. The second half is not a detachable dream, because details cross leak, identities overlap, and the loop structure binds the opening and closing around it. The film punishes you for treating a region of its narrative space as ontologically void.

In Williamson’s terms, shifting domains can be made consistent, but it introduces a question. Why should the logic of modality and quantification have that shape, rather than one in which the domain is fixed? What theoretical work is the shifting doing? Often, it is doing the work of protecting pre theoretical intuitions about existence, especially the intuition that to exist is to be concrete.