Ernest Gellner: Some Reflexions Twenty-six Years On From His Death

By Alan Macfarlane

Part One

Ernest Gellner - the Life and the Works

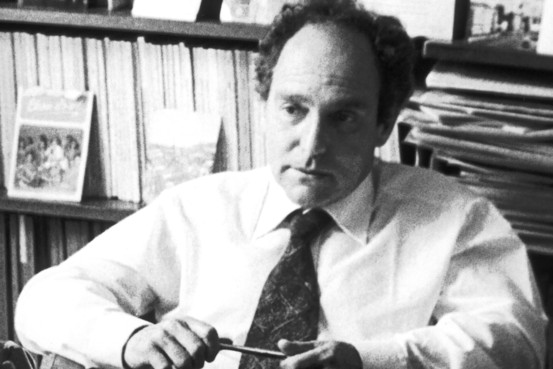

How I knew Ernest

As an academic one is always on the look-out for models or exemplars. In particular, one is half-searching for contemporaries, probably older than oneself, who seem to have a touch of greatness, to be destined to be among the immortals. Ernest Gellner, the distinguished philosopher, sociologist and anthropologist is one of the few I have met in the humanities and social sciences who may fit into this category.

I first heard about Ernest in the early 1960s. One of my teacher’s at Oxford was Lady Rosalind Clay. She had shown me a series of articles in the New York Review of Books by Ved Mehta where he had interviewed a number of historians who were in heated argument about the rise or non-rise of the gentry. Mehta also wrote another series concerning the controversy stirred up by Ernest’s first book, Words and Things , which was an amused but damaging attack on Oxford linguistic philosophy and in particular the later Wittgenstein. The journal Mind had refused to let it be reviewed, to which Bertrand Russell and others had objected. I distinctly remember Mehta’s account of his meeting with Ernest (the articles were reprinted in The Fly and the Fly Bottle ) in which he described how Ernest wrote by dictating into a tape-recorder (which Ernest vehemently denied, though I later saw him use a similar method).

I came into personal contact with Ernest in 1967 when I was doing my M.Phil. in anthropology at the L.S.E., where he was a Professor. I remember being forcefully struck by two things then. One was his article on ‘Concepts and Society’ which I finally tracked down and xeroxed and read with enormous excitement. It was witty, liberating, made huge sense in treating concepts in a Durkheimian way. The other was meeting Gellner. Small, limping and with a walking stick, a huge forehead, he looked the arche-typical philosopher.

I attended a seminar or two with him and was touched after that by the fact that when we met he would politely stop and ask how I was. This may have been part of what he disparagingly called his headmistress approach. A headmistress when talking to the teachers at the start of the term warned them, 'Be nice to the little girls, however horrid they are, for you never know who they may marry'. In fact, I think Ernest was just being nice, but felt embarrassed at being caught out as soft hearted. I felt honoured and proceeded to read more of his work.

In fact I think I was quite critical of the first book I read, Thought and Change. I was going through a left-wing and ecological phase. I believed in doom and gloom and was convinced that the industrial revolution had been a prelude to real problems. Ernest’s contention that we had overcome the Malthusian problem of population and scarcity through technology struck me as over-optimistic. He argued that Malthus’ law had been inverted; production now grew exponentially and population in only a linear way, so that improvement and growth of affluence was built into the system. I felt he was wrong, but could not quite summon up the arguments as to why. But the scintillating and amusing nature of the book captivated me.

Anyway, I was impressed to meet the author who had caused such a storm by his first book. And I suspect that his memories of that experience gave Ernest a particular sympathy for me when the Origins of English Individualism (1978) came out. Not only did he give the book a boost by choosing it as his book of the year, but also he used to ask me sympathetically whether the more savage reviews were worrying me.

*

We remained in touch after I went to do my fieldwork in Nepal in 1968. He was an admirer and friend of my supervisor Fürer-Haimendorf which may have helped. Ernest was contemplating changing his main ethnographic field from Morocco to the Himalayas and nearly became a Professor at Kathmandu in the early 1970’s. He loved mountains and I think this what attracted him. Anyway, I remember he went trekking in the Annapurna’s in 1976 and carried a copy of the proofs of my book on Resources and Population with him. The review he wrote, which was lengthy and favourable, though there were some serious questions and re-interpretations as well, formed the front cover of the Times Literary Supplement (‘High and Low in the Himalayas’). It helped publicize the book and put me further in his debt.

By this time I was teaching in the Department of Social Anthropology and in 1976 Ernest came to stay with us. Characteristically he brought a tent and car and canoe, as well as one of his children, for a trip up the fenland rivers. He came into our spacious house to watch his favourite football team (from memory, Portsmouth). But despite our entreaties to use one of the spare bedrooms, insisted in plodding out in the pouring rain late at night to set up his tent by the headlights of his car. Obstinacy was his middle name, an obstinacy which helped him fight the deteriorating and wasting disease in his hips which made his active life so especially difficult.

A year or two later that he became a yearly visitor to Cambridge. I was in charge of the ‘Theory’ paper in the Part II of the Anthropology Tripos and every year would arrange for Ernest to give four lectures in the summer term on grand social theory. I think it must have started in about 1979. The first year he gave the four lectures without notes and at the end asked whether I could collect some notes taken by students as he would like to work them up into a book and did not know what he had said! I was amazed, but procured some lecture notes. The same thing happened the following year, so the third year I arranged for the lectures to be tape recorded.

They were wonderful lectures. We could see an immensely powerful and erudite mind, trained in analytical philosophy, sociology and anthropology (he had been Professor in all three) talking as an equal about great social thinkers and their theories. In particular he talked about the Enlightenment figures and especially his favourite David Hume. Parts of the lectures went over my head, as they did with the students, but one could see the general question that lay behind them. This question was how this amazing modern world emerged against all the laws and predictions of the great thinkers. It was the Enlightenment question, being re-asked two centuries later with the experience of fascism (by which his own Czechoslovakia had been destroyed) and communism, and Ernest’s close experience of Islam to add to the data. Little diagrams of submarines with periscopes which were later published were drawn on the board. All the time one felt in the presence of greatness, and of someone who spoke directly about the big issues.

After the lectures we would take wine and sandwiches to King’s College Fellow’s garden and talk into the afternoon. It was very special, and made more so when I expressed an interest in sailing and Ernest suggested that we go sailing with him at Chichester, where he had a small boat. We did so two or three times, staying a night or two. He even let us use the boat on our own. I can’t say I enjoyed the sailing much, but talking to Ernest made it special, though there were long gaps in the conversation as he had the tendency to sit for long periods without saying anything.

Our friendship and my admiration increased, so that when Jack Goody retired and the Wyse Chair was advertized I became one of his chief internal supporters. It was a close thing, but he was elected. In the summer of 1983, just before he arrived to take up the post, we had our last easy, relaxed, time together before the relationship changed to the more formal one of Professor and Reader. He invited Sarah and I down to the peasant hamlet he had bought high up on a north Italian hill-side at Fontanilli. We took our daughter Astrid with us (who had always got on well with Ernest, playing long-distance chess with him etc.) and first stopped off at Jack Goody’s house in the south of France. There we found Jack hectically busy laying drains so that Esther mainly entertained us. We then went on to Fontanilli. There we sat and drank wine in the evenings after days walking through the hot, abandoned, terraces full of thyme and butterflies.

We did not talk much about our own work. I must have been working on yet another draft of kinship and marriage or perhaps just finishing my book on the Justice and the Mare’s Ale . Only later did I realize that the book Ernest was writing (sitting in a deck chair with a small typewriter) was a draft of one of his most famous and widely read books, Nations and Nationalism .

So in October 1983 Ernest came to Cambridge as William Wyse Professor, where he would remain until 1991. During these eight years he struggled to master the complexities of the ancient Cambridge administrative and political system. He was used to considerable secretarial support and a centralized university at the London School of Economics. The distributed power, endless decisions, leading by example, responsibility without power, of Cambridge did not appeal to him. He enjoyed intellectual encounters and occasions, some sparkling seminars and teaching good graduates, he enjoyed the social life of King’s, but never mastered the basics of how the University worked. A combination of being too logical in his thought, and a basic desire to get on with his writing in the most productive era of his life, meant that administration was kept to a minimum.

Thus the period with Ernest exactly coincided with the period when I returned to work on Nepal, and also the Naga project, both projects fully supported by him. But in terms of deep, continuous, concentration needed for serious writing, it was difficult., partly because I was having to put a lot of energy into supporting him in the administration of the Department, including acting as Head of the Department for two years while he was absent, and over the summer. Yet having Ernest around, our discussions and reading his books, was a great inspiration and this fed in at a deeper level.

Ever since my undergraduate days I had asked basic questions about our extraordinary modern world and how it had emerged, the origins and effects of the industrial revolution, the nature and origins of modernity and so on. This lies behind all my works. But I seldom encountered people who asked such simple, wide, questions. Even Keith Thomas was confined to a few centuries in one country, and Peter Laslett likewise. Ernest was like Jack Goody in his breadth. But while he lacked Jack’s ethnographic nose, political skills, or interest in material life, his philosophical background was stronger. He was the first person I had met who asked the really great world-important questions in the tradition of the Scottish Enlightenment and Max Weber. He also had such a lofty and incisive mind that he made wonderful syntheses of complex data.

At the time he was probing these questions in books like Sword, Plough and Book , and a number of papers. We disagreed somewhat about where the answers lay, but there was no doubt in my mind that he was asking the right questions. My two books, Riddle of the Modern World and Making of the Modern World , published after his death (the former dedicated to him and with a chapter on him) are really extended conversations with Ernest, an attempt to persuade him to accept my views. His experience had reminded him of what most of us have forgotten – the extraordinary revolution that has occurred.Now that, in a Conference in Prague in May 2021, we have just celebrated his remarkable life, twenty-six years after his death in 1995, I find that I can stand back from this remarkable man and think more about his strengths and weaknesses. This account will try to explain how I have tried to answer some of the questions which Ernest put to me in our conversations, but which I could not see the solution to during his lifetime. First, however, who was this man and what were some of his internal contradictions.

The life and the contradictions

Ernest Andre Gellner was born in Paris on 9th December 1925, the son of a Jewish lawyer from Czechoslovakia. The family lived in Prague until the German occupation in 1939, when they moved to England. Gellner was sent to St. Alban's County Grammar School, from which he won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. But his studies were interrupted when he left for a year to serve as a private in the Czech Armoured Brigade. He was at the siege of Dunkirk, joined the victory parade in Prague and then returned to Oxford. In 1949 he obtained a first in P.P.E.

Gellner went to Edinburgh for two years on an assistantship in philosophy and became a lecturer in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics. He was already highly critical of his earlier discipline, Oxford philosophy, and began work on a book, Words and Things (1959) which would cause a great stir in the profession. He was also critical of the evolutionary sociology of Ginsberg and Hobhouse at the L.S.E., as well as Parsonian functionalism. There he became attracted to anthropology, where Bronislaw Malinowski's influence was still strong. In 1954 he went climbing with the L.S.E. mountaineering society in the High Atlas in Morocco, and thus began his fieldwork for an anthropology Ph.D. under Raymond Firth and Paul Stirling, subsequently published as Saints of the Atlas (1969). This was a brilliant analysis of the way in which segmentary lineage systems and holy mediators maintained order in the absence of an over‑arching state.

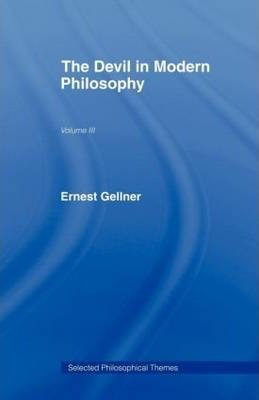

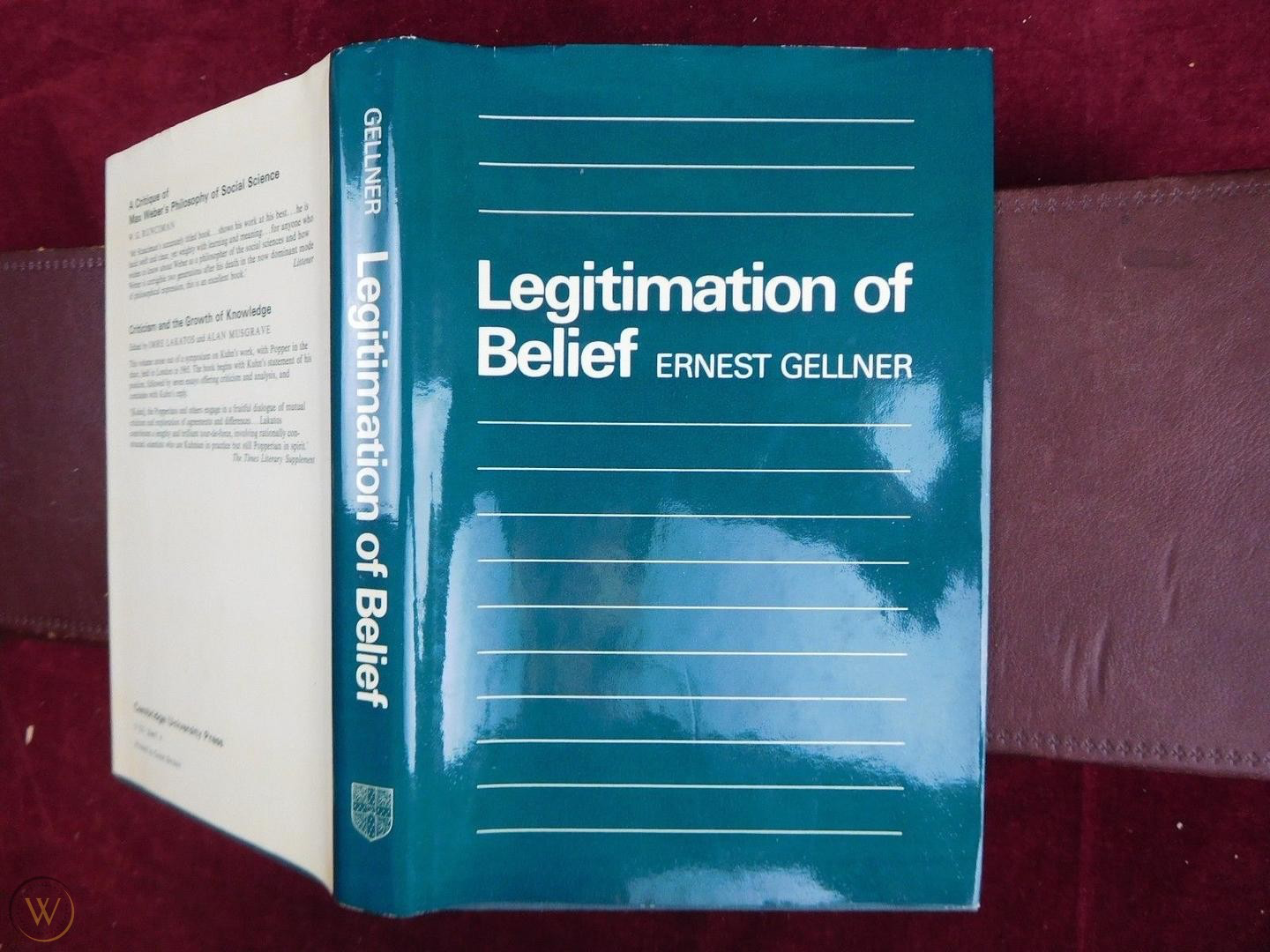

In 1962 he received a Personal Chair at the L.S.E. as Professor of Sociology with Special Reference to Philosophy. He wrote a number of works connecting these disciplines, notably Thought and Change (1964), Cause and Meaning in the Social Sciences (1973), Contemporary Thought and Politics (1974), The Devil in Modern Philosophy (1974), Legitimation of Belief (1975), Spectacles and Predicaments (1979) and Nations and Nationalism (1983). He also continued his studies of Islamic societies, making eight field‑work visits to Morocco and publishing Muslim Society in 1981. He was made a Fellow of the British Academy in 1974. Gellner came to Cambridge as William Wyse Professor of Social Anthropology in 1984 and was elected to a Professorial Fellowship at King's. He retired as Professor in 1993, but remained a Supernumery Fellow of King's until 1995. He was Resident Professor and Director of the Centre for the Study of Nationalism in the Central European University of Prague from 1993 to 1995. During his period at Cambridge he was extremely productive, publishing The Psychoanalytic Movement (1985), The Concept of Kinship (1986), State and Society in Soviet thought (1988), Sword, Plough and Book (1988), Reason and Culture (1992), Postmodernism, Reason and Religion (1992), Encounters with Nationalism (1994) and Conditions of Liberty (1994), Anthropology and Politics (1995). His short book on Nationalism (1997) and Language and Solitude (1998) were published posthumously. He died peacefully in Prague on 5th November 1995, leaving his wife Susan and his children David, Sarah, Deborah and Ben.

*

When Ernest came to Cambridge he regretted the absence of more of a 'community' in the Department of Social Anthropology and at King's. Yet he also held what chances there were of fuller participation at arm's length. He played little part in the formal, committee life of King's, and likewise hated involvement in University administration, summing up his feelings in the same 1990 interview with John Davis, thus: 'And then administration at Cambridge is dreadfully participatory, and I prefer administration being done by professional administrators...' He never felt it was worth his energy to understand how the complex, feudal, system of Cambridge worked. It was one tribe too many.

Another linked ambivalence lay in his attitude to relativism. At one level, much of his life was an attempt to preserve the certainties of the Englightenment, to hold back the forces of relativistic unreason. Thus his deepest battle was against Wittgenstein's philosophy which, as he saw it, was the ultimate relativistic faith. In the interview of 1990 he noted that 'Wittgenstein's basic idea was that there is no general solution to issues other than the custom of the community. Communities are ultimate...And this doesn't make sense in a world in which communities are not stable and are not clearly isolated from each other.' Gellner was not prepared to let each community dictate what was right. Even as a little boy he was aware of an inner light by which his community might be shown to be wrong. In the same interview in 1990 he told how in Czechoslovakia he went to a summer camp where the flag was raised and an oath of loyalty was sworn. He always missed out one world of the oath not because he had an intention of committing high treason, 'But I didn't see why I should close my political options so early. I didn't wish to bind myself. It seemed to me slightly premature, and I hadn't figured it all out.' In a way, he maintained this attitude throughout his life, hovering on the edge of Karl Popper's seminar, of circles of philosophers, sociologists and anthropologists. It was that ideal contradiction between participation and observation which is the essence of the anthropological method. But very few are able to carry it out consistently throughout their personal and professional life. It is what made him a unique commentator on the West, Islam and the Soviet Union.

Yet however strong his dislike of relativism and his warnings against being too 'charitable' to the 'irrational' in other societies, in relation to his two major encounters with other civilizations he found himself forced into a relativist position. During the Rushdie debate, he found himself defending Islam against the demands for absolute freedom put forward by many western intellectuals. He argued that one society should not be measured by the yardstick of another ‑ a slide towards relativism he would have castigated in others. Or again, in a posthumous essay on the break‑up of the Soviet Union, he provided an elegant and sad lament for the too‑rapid destruction of a system which he hated, but which he nevertheless saw gave moral dignity to its members. He thought it should have been allowed to alter from within, and much more slowly. The difficult middle position he tried to maintain is summarized in a sermon in King's College Chapel in 1992 when he described the world as divided into fundamentalists, relativists and 'Enlightenment Puritans'. He saw himself as falling in the last category ‑ in many ways itself a contradiction in terms.

His lifelong assault on Wittgenstein was part of this 'horrified fascination'. He then moved on to another closed system, Islam, which refused to separate power and cognition, politics and religion. 'Islam initially intrigued me because of its unintelligibility, given certain European assumptions.' Marxism and Freudianism were both 'part of the intellectual atmosphere in which I grew up' and there was a 'persistent inner dialogue' with them. This dialogue was expressed in his various books and articles on the Soviet Union, and his book on the Psychoanalytic Movement. In his later life, Gellner saw a return of the totalizing Wittgensteinean monster in another branch of what he termed the 'hermeneutic plague', namely, post‑modernism. He launched a savage attack on a mode of thought both corrodingly relativist and absolutist in its way in Postmodernism, Reason and Religion (1992). In a synthesis of much of his central thought in Conditions of Liberty (1994), explicitly referring to Popper in its sub‑title 'Civil Society and its Rivals', he provided a brilliant specification and defence of the 'open', liberal society.

Yet there is a contradiction here also, for while attacking all complete and neat systems, Gellner himself wished to create an over‑arching theory. His own life, poised between thought systems and cultures, had put him in an unique position to appreciate the 'great transformation' of modernity. This he described in the 1990 interview as follows. 'The difference between the agrarian religious world and the industrial scientific one has always been for me absolutely central to understanding the world.' 'The emergence of an open system in north‑western Europe...is a central fact about the world, about the human condition. There have been transitions from societies based on a stable technology, a stable faith, hierarchical organization, cultural stratification, and all the rest of it to societies based upon economic growth, a kind of universal bribery fund with a commitment to secure material improvement. That involves an unstable occupational structure, which in turn involves a measure of egalitarianism, a homogeneous culture, because people have to communicate with each other, which involves nationalism.' This he thought was "the enormous transition which I think is the central fact about our world" and was "my central preoccupation".

[Hume]

[Hume]

The early clash between eastern and western Europe in his upbringing was reinforced by at least three further intellectual and social experiences which heightened his awareness of the peculiarities and precariousness of our civilisation. One of these was his professional interest in the great philosophical watershed between the ancien regime and modernity which took place in the eighteenth century and particularly in the Scotland of his beloved David Hume. Here Gellner found a specification of the foundation of the new world and all its strangeness, which was given further precision by his other mentor, Kant.

The second reinforcement came from his professional involvement with Islam. This provided him with an invaluable counter-model. He approvingly quoted Tocqueville on the fact that 'Islam is the religion which has most completely confounded and intermixed the two powers...so that all the acts of civil and political life are regulated more or less by religious law. Islam made Gellner deeply aware that the mixing of religion and politics is the normal state of mankind: their separation in parts of the world is a recent peculiarity. The way in which Islam continued to operate effectively despite this lack of separation continued to puzzle him. Islam 'exemplifies a social order which seems to lack much capacity to provide political countervailing institutions or associations, which is atomized without much individualism, and operates effectively without intellectual pluralism.'

Thirdly, there was Gellner's continuing work with the only other major 'totalitarian' or 'closed' system that existed for most of his lifetime, communism. Whereas Islam embeds politics within religion, the Soviet world tried to embed economy, society and religion within the polity. He wrote that 'Under the Communist system, truth, power and society were intimately fused.' Or, writing of Kolakowski, 'The underlying moral aspiration which he credits to Marxism is the abolition of the separation between the social and the political.' The collapse of this closed world provided Gellner with the chance to undertake a post-mortem. The surprise and opportunity perhaps helps to account for the fact that some of his most inspired writing occurred in the last six years of his life, after 1989. As he himself put it, 'It is this collapse which has taught us how better to understand the logic of our situation, the nature of our previously half-felt, half-understood values. We now see the manner in which they emerge from the underlying constraints and strains of our condition. It provides a better way of understanding society and its basic general options.'

*

Returning to the man himself, it is clear that one of the reasons why Gellner's attacks on others caused such irritation was because he tended to treat his opponents in their social and personal context. He saw their concepts as merely one aspect of their lives. This broke a recent English tradition of tending to keep the private and the public apart. Instead he returned to the techniques of irony and satire of Pope and Dryden. Given this approach, it does not seem unfair to end by showing a little of Gellner the man.

Something that struck most people was the contradiction between the acerbic and often cruel debater, and the enormously kind and gentle human being. At the personal level, as his numerous friends and pupils could witness, his life was full of little acts 'of kindness and of love'. He was also extremely generous with his time, possessions, support. At times he felt that all this natural kindness might be taken as a sign of weakness, so he used to try to justify it as a Machiavellian strategy.

Memory of his roots made him an extraordinary modest person, self depreciating, humble and somewhat shy. Although his large forehead and reflective manner proclaimed the intellectual, many students were amazed to find that the unassuming man they had been talking to at a party was the great Professor Gellner. Yet when he turned from the private to the public, when he lectured or wrote, he sounded like an Old Testament prophet, full of certainty and authority and verging on the edge of arrogance. He hated pomposity and was the most equitable and egalitarian of people, treating students, strangers and others all alike. Yet again there was a contradiction for he freely admitted to social snobbery and his desire to be a member of the best clubs.

He was an urbane person who loved Prague and other cities. Yet he also loved the countryside. He rejoiced at having to register as a 'peasant' when he bought his house in Italy. There, drinking rough wine under the vines in the lavender scented terraces, he seemed entirely at ease. He relished the challenge of mountains and whether in the High Atlas or the Himalayas, pushed his body against the wilds. He enjoyed sailing and canoeing. All these physical efforts seemed to be part of his obstinate battle against the crippling osteoporosis which increasingly affected him and kept him in constant pain during the latter part of his life.

The obstinacy, which showed itself in physical exertion, was a very strong characteristic. Once he had decided on a course of action, it was almost impossible to dissuade him. This obstinacy was a trait which again one found in his writing. He was under enormous pressures to be quiet, to accept the blandishments of snobbery and power. But like a mischievous boy, he refused to conform.

He saw himself as a secular Puritan, a descendant of Jan Hus and an opponent of the Counter Reformation. In the 1990 interview he admitted that "I have deeply internalised the values of the puritan wing of Abrahamic monotheism." His chief weapons against the monsters of power were rational, calm, logical, learned thought, combined with irony and satire. He was a devastating opponent because of his sense of humour and sense of the ridiculous. A final series of contradictions lay in his sense of loneliness, reserve and shyness on the one hand, with great warmth and an out going nature. He was intensely proud and protective of his family and depended hugely on his wife Susan, whom he married in Gibraltar in 1954. He made innumerable friends and was an inspiration to generations of students through his writings and lectures.

*

Gellner's writing was always lively and often brilliant, going straight to the heart of complex and important matters with an awesome combination of philosophical, anthropological and sociological knowledge. His use of concrete metaphors was often startling and made one see things in a new way. He could be a marvellous lecturer lecturing without notes from an inner store of memories and associations. His brilliance and the carefully arranged structure in his mind are well illustrated by the story of how on one occasion he came to give a lecture on the famous 'isms' of sociological theory and was just embarking when a student pointed out that in fact this was the second of a series on Islamic politics and religion. With a one minute pause, he proceeded to give a brilliant lecture on that subject.

In many ways Gellner was a 'hedgehog' who knew 'one big thing', namely that the great puzzle is the unexpected emergence of the open, expansive, modern world. Yet he was perhaps too much of a fox, who is interested in many smaller things, to be able to provide more than a tantalizing glimpse of an answer. He does not seem to have developed any sophisticated system of annotating books which would allow him to accumulate knowledge. He thus relied largely on his own intuition and memory. This gave him the freedom to move very fast, to concentrate on the problems of the moment. Thus he was a superb essayist and controversialist. Yet the longer and deeper work which would be needed to answer his fundamental questions, requiring detailed evidence from a wide range of sources, systematically gathered, could not be approached in this manner. The notebooks or indexes of a Darwin, Marx or Frazer do not exist. Perhaps he tended to write too fast, work too hard, to be too easily side tracked, to love controversy too much. Yet he is certainly one of the major intellectual figures of the second half of the twentieth century, a name and reputation which will live on in the history of thought. In the man and in the writing one felt the touch of genius, the ability to ask the right and perennial questions.

Part Two

Ernest Gellner and the Conditions of the Exit

One of the problems to which Gellner addressed his thought, particularly towards the end of his life, was the very one which had been at the heart of the lived experience of the Enlightenment thinkers. How had the 'great transition' from the hierarchical, agrarian world occurred? Gellner's first task was to re-enforce the message of Montesquieu and Smith that the escape went against the tide of previous history. He does this by elaborating and re-confirming one of the central themes in much of their work, namely that the normal tendency is towards hierarchy and increasing predation.

The law of increasing predation.

Based on his experience in Islamic and Communist societies, and his reading of history and anthropology, Gellner suggested that if we looked at the last ten thousand years of human activity we could discern a powerful law which seemed to govern agrarian societies. The law was that they were bound to hit a ceiling, a 'high-level equilibrium', where political violence curbed economic growth.

Gellner put this law as follows. 'Material surplus generally, though not universally, makes for political centralization. And although political power and centralization in agrarian society is fragile, often unstable, it is nevertheless extremely pervasive.' This is because 'The moment there is surplus and storage, coercion becomes socially inevitable, having previously been optional. A surplus has to be defended. It also has to be divided. No principle of division is either self-justifying or self-enforcing: it has to be enforced by some means and by someone.' It is also the case that 'Wealth can generally be acquired more easily and quickly through coercion and predation than through production.' Consequently we find that in agrarian societies it is the warriors who are the highest group: specialists in violence are generally endowed with a rank higher than that of specialists in production.' It is a world of competition, violence and scarcity. Thus 'Roughly, the general sociological law of agrarian society states that man must be subject to either kings or cousins, though quite often, of course, he is subject to both.'

[Cover of Leviathan by Hobbes]

The miraculous exception to the tendency.

From our vantage point at the end of the twentieth century, we can see that the above is a tendency, rather than an iron law. In other words, there are exceptions. There have been temporary and short-term exceptions, but Gellner's chief interest is in the major exception when something very unusual happened. 'Certain societies, whose internal organization and ethos shifted away from predation and credulity to production and a measure of intellectual liberty and genuine exploration of nature, became richer and, strangely enough, even more effective militarily than the societies based on and practising the old martial values. Nations of shopkeepers, such as the Dutch and English, organized in relatively liberal polities, repeatedly beat nations within which martial and ostentatious display, dominated and set the tone.' This is the miracle, and it happened in north western Europe, at the very time when the Enlightenment thinkers started to analyse it. : 'Once only did the balance change definitively, under exceedingly favourable circumstances - eighteenth century England...'

Not only was there sustained economic growth, but the natural tendency towards growing absolutism and greater stratification and the suppression of free thought, all were simultaneously broken. The escape from the domination of thought by the political and religious powers was extraordinary. 'The dependence of the individual on the social consensus which surrounds him, the ambiguity of facts and the circularity of interpretation are all enlisted in support of the fusion of faith and social order. This is the normal social condition of mankind: it is a viable liberal Civil Society, with its separation of fact and value, and its coldly instrumental un-sacramental vision of authority, which is exceptional and whose possibility calls for special explanation.' Equally strange was the escape from the tendency towards 'caste'. Thus the 'astonishing egalitarianism of modern society...has inverted the long-standing and seemingly irreversible trend of complex societies towards ever-increasing social differentiation and accentuated, formalized, hierarchy.'

Of course the escape may only be temporary, just as it is fragile. The open and expanding society was very nearly snuffed out in the Second World War. Only very recently has it become obvious that the other option, communism, is very unlikely to take over the world.

Thus Gellner had specified a puzzle, the exit of one part of the world from the apparently closed circle of agrarian political systems. He noted that 'On one occasion and within one particular tradition, however, one special Reformation was much more successful than the others, and transformed the north-western corner of one continent sufficiently to help engender an industrial-scientific civilization.' He sees the sociologist's central concern as the need to 'explain the circuitous and near-miraculous routes by which agrarian mankind has, once only, hit on this path; the way in which a vision not normally favoured, but on the contrary impeded by the prevailing ethos and organization of most human societies, has prevailed...it is most untypical. It goes against the social grain.'

The disenchantment of the world.

One central 'condition' of the exit from agrarian civilization, lies in the development of religion. Like Weber, Gellner does not suggest that Protestantism intentionally or directly caused capitalism. Firstly the famous ascetic virtues of hard-work, honesty and accumulation were an accidental by-product of the Reformation. Thus 'one may also accept the Weberian argument that virtues which could only initially emerge as the by-product of bizarre religious conviction, because their beneficent effects were not known and were anticipated by no one, nevertheless become habit-forming and are perpetuated, once their place in a modern economy is properly and widely understood.'

Part of what Protestantism did was to push to one extreme a general tendency in much of western Christianity towards an attack on a magical and ritual embededness. Some of the explanation for the growth of an unusual thought style in the west from early on lies in Christianity, that is to say 'the impact of a rationalistic, centralizing, monotheistic and exclusive religion. It is important that it was hostile to manipulative magic and insisted on salvation through compliance with rules, rather than loyalty to a spiritual patronage network and payment of dues.' Gellner outlines this great transition which occurred over two thousand years ago with the development of Christianity out of Judaism.

Over time, this asceticism, the tension between the material and spiritual world, tended to become overlain in Catholicism with a world of miracles and magic. Protestantism was the extreme attempt to restore it to its original anti-magical cleanliness. This movement towards a 'disenchanted' world is an ideal background for orderly science and orderly capitalism.

The breaking of the alliance of priests and rulers.

Gellner argues that two revolutions were needed. The first was to separate thought from the material world and put it into the hands of the clerisy. The second separation, between the forces of coercion and those of cognition, between rulers and clergy, is equally important. He argues that 'It is hard to imagine perpetual and radical cognitive transformations occurring in a society in which the old alliance of coercive and clerical elements continues to prevail. They would suppress and smother it...' How then did this second revolution occur?

Gellner suggests that something special happened in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which set thought free from its previous embedding in politics. For example, 'Descartes proposed and pioneered the emancipation of cognition from the social order: knowledge was to be governed by its own law, unbeholden to any culture, any political authority.' This first emancipation, which the Counter-Reformation had tried to crush, only became firmly established after the eighteenth century Enlightenment. Religion restricted its claims to areas which 'do not prejudge the results of free and empirical inquiry'. How then did this happen?

Clerics and rulers in confrontation.

Puzzling on how mankind escaped from the joint domination of priests and kings, Gellner developed the idea that it was because the clerics and the rulers fell out with each other. The 'normal' situation in agrarian civilizations was described by Durkheim, who 'sketched out what is really the generic social structure of agro-literate societies, namely government by warriors and clerics, by coercers and scribes.' Yet instead of this usual Caesaro-Papist concordat, the tension between Church and State is a peculiar western characteristic - as compared, for instance, to India or China. Gellner cites Hume's explanation for the toleration in England or Holland; 'if, among Christians, the English and the Dutch have embraced principles of toleration, this singularity has proceeded from the steady resolution of the civil magistrate, in opposition to the continued efforts of priests and bigots.' But why, unusually, were the civil magistrates opposed to religious extremism?

The key, Gellner suggests, may have been in the stale-mate between a powerful Church and a powerful State, both seeking a monopoly yet neither able to obtain it. 'The separation of, and rivalry between, these two categories of dominators may well constitute one of the important clues to the question of how we managed to escape from the agrarian order. Priests helped us to restrain thugs, and then abolished themselves in an excess of zeal, by universalizing priesthood.'

The victory of production over predation.

[Louis XIV an absolutist predator]

[Louis XIV an absolutist predator]

The second main line of Gellner's explanation lies in the relation between the political and the economic. His first premise, as we have seen, is that as societies develop into what we call 'civilizations', predation (politics) will dominate production (economy) and constantly restrict its development. It is a kind of Malthusian law of power. If through some accident or discovery, wealth is increased, it will lead to a rise in predation which will reduce mankind back to that world of violence from which momentarily it seemed to be lifting itself.

Of course, from time to time, the relations of production and predation are reversed, and there is a period of economic and cognitive growth, as in Greece or the Italian city states. 'Under favourable circumstances, power had very occasionally moved from thugs to traders even in earlier periods: but as long as there was a kind of ceiling on economic development, the shift did not proceed too far and either reached a limit beyond which it could not go or was eventually reversed.' In general, looking over the long history of mankind up to the middle of the eighteenth century, it seemed true that 'political considerations trumped economic ones and the economic side of life simply could not be granted full autonomy - in other words, a market society was impossible - because the economy was so pathetically feeble.'

The normal tendency was for wealth-producing oases to be over-run by the surrounding military powers, as happened in Italy, southern Germany or the Hanseatic League. 'Commercial city states are a fragile rather than a hardy plant. Why should the free merchants of north-west Europe fare any better than their predecessors who lie buried in the historic past?' How then did a temporary reversal become permanent? How was the 'stability or stagnation of productive forces - which, all in all, applies to agrarian society ... eventually replaced by a permanently growing economy.'? Adam Ferguson had noticed, like Adam Smith, that it was happening, yet 'He does not adequately analyse the distinctive conditions which have led in modern north-west Europe to the subordination of coercers to producers.' He does not explain how it was that 'under the new dispensation, the relative attractiveness of production and coercion changed. It is no longer more honourable to become rich by warfare rather than by trade.' The subduing of political by economic power was the great triumph. 'Marxism made it a taunt that the bourgeois state was merely a kind of executive committee of the bourgeoisie: that this should ever have become possible is perhaps mankind's greatest social achievement ever.'

The deus ex machina: technology and science.

Gellner appears to explain the sudden dramatic switch by invoking a new, special, factor, namely the development of technology and science. There were two distinct phases. As the change began, the important thing was that there was technological growth, but that it was not too obvious. This is put in Gellner's words thus. 'So early development may well have depended on the relative feebleness rather than the power of innovation. In fact, by the time the new world emerged in full strength, and its implications were properly understood, it was too late to stop it. It had been camouflaged by its gradualness, and that was made possible by the relatively non-disruptive nature of its techniques.'

This is why Gellner always stresses an expanding but feeble technology as one of his essential pre-conditions. Among the conditions of the escape were 'above all, a fairly feeble technology, one just about capable of improving significantly on traditional methods of production, and making sustained innovation appear attractive, but not capable of very much more. A feeble technology of such a kind can be given its head and it will not disrupt either the social order or the environment, or at any rate not too much.'

As Perry Anderson summarizes the Gellner argument here, 'In substance, his argument has consistently been that science - and science alone - brings modern industry, that yields mass prosperity, which permits effective morality. It is the material affluence afforded by scientific reason that is its epistemological trump-card.' It also tipped the balance politically, enabling the new formation to win the Darwinian competitive and selective war. 'In these circumstances, within the un-throttled societies production becomes a better path to wealth than domination. In traditional societies, he who has political power soon acquires wealth as a kind of consequence.'

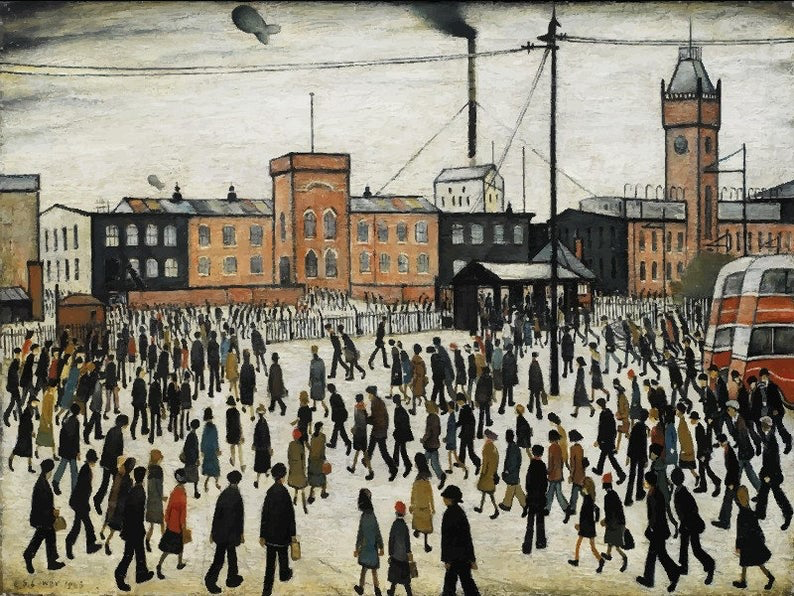

The fortunate miracle of the industrial revolution.

[LS Lowry: Going To Work]

The permanent transformation, however, would not have occurred if it had not been for the fact that by complete chance, just as the early phase reached its limits in the early seventeenth century in Europe, there was a change of gear. Without any warning and without anyone being able to anticipate it, two 'revolutions' occurred, which finally coalesced and confirmed the switch from predation to production. These were the enormous surge in knowledge and productive power created by the scientific and industrial revolutions.

Smith and Ferguson had been right to be pessimistic given anything that had happened in the past on earth. Yet both Smith's economic and Ferguson's political pessimism 'came to be invalidated by the same factor, by the tremendous expansion of productive power consequent on the impact of scientific technology.' In the eighteenth century, a phenomenon whereby 'commerce and production ... take over from predation and domination' for the first time in history perpetuated itself because it was 'accompanied by two other processes - the incipient Industrial Revolution, leading to an entirely new method of production, and the Scientific Revolution, due to ensure an unending supply of innovation and an apparently unending exponential increase in productive powers.' Thus the 'entire shift from valuation of coercion to valuation of production was only possible because, rather surprisingly, indefinite, sustained, continuous technological and economic improvement had become possible.'

The virtuous become the strong.

It has often been observed that through history the balance between offensive and defensive weapons has changed the nature of war and peace. What Gellner is basically arguing is that for the first time in history an even deeper technological shift occurred whereby the tools of production became more powerful than those of predation. A rich country with a navy and small mercenary army could resist a larger, more warlike but poorer country. For the first time in history more power and wealth could be made from producing things than from violent predation on others.

What happened was that a country devised a method of rapidly becoming rich by increasing production, which meant that it was also able to became the politically dominant power. Technological expansion became a virtue, rather than a threat. The 'fittest' were not those who pursued the straight path of predation, but those who put much of their energies into production. 'Astonishingly, the regime in which oppression and dogmatism prevailed was not merely wicked, but actually weaker than societies which were freer and more tolerant! This was the essence of the Enlightenment.' As Mandeville might have added, 'private affluence, public power'.

Thus 'sustained and limited' expansion and innovation 'finally turned the terms of the balance of power away from coercers and in favour of producers. In the inter-polity conflict, no units managed to survive and to continue to compete if their internal organization was harsh on producers and inhibited their activities or impelled them to emigrate.'

Thus the 'fittest' were now those who espoused that mix of openness and technological progress whose model was England. 'The economic and even military superiority of a growing society then eventually obliged the others to follow suit. Natural selection secured what rational foresight or restraint had failed to bring about.' 'So all the states in the relevant part of the world were in the end obliged to emulate the liberal path to economic prosperity, or at least some aspects of it, in the hope of augmenting their power and relative international position.' In pursuing this argument, we can see Gellner considering themes which were elaborated by Montesquieu and Adam Smith. The great difference is that Gellner can see the longer term outcome, can add the industrial revolution, and can even see a modern re-run of the process in the collapse of communism in the face of the open capitalist west.

The necessary political configuration of Europe.

Why then did the change occur first in western Europe? Here Gellner elaborates a theme which also echoes the Enlightenment theorists. It could happen because Europe was split into a number of medium-sized states. Usually an improvement in technological power will strengthen domination 'But in Europe the process was taking place within a multi-state system, and the thugs were unable to use growth to strengthen themselves everywhere at the same time and to the same extent. The various thug states were also engaged, as was their habit and joy, in conflict with each other. Those which had tolerated or were for one reason or another obliged to tolerate, prosperous and non-violent producers in their own midst, suddenly found themselves "more" powerful - because endowed with a bigger economic base - than their rivals.'

In huge absolutist Empires, predation will eliminate production. 'But in a plural state system, in which other states prosper dramatically and visibly, the throttling and throttled systems are in the end eliminated by a social variant of natural selection. In a multi-state system, it was possible to throttle Civil Society in some places, but not in all of them.' The continuous growth produced by science and technology not only provides an adequate 'bribery fund' to buy off the powerful, but it will also make it possible to solve the problem of keeping people in order without naked force. Thus it is also the basis for democracy. 'Only in conditions of overall growth, when social life is a plus-sum, not a zero-sum game, can a majority have an interest in confirming even without intimidation.'

Summary of the Gellner argument.

In summary, then, Gellner has put forward both a puzzle and several hypotheses to suggest an answer. The puzzle is that until the middle of the eighteenth century it seemed as if it was a law of agrarian societies that they would run into a high-level equilibrium trap of a 'Malthusian' kind. Increases in production would lead to increasing predation and there would be an inevitable crash.

Yet, for the first time in history, a corner of the world emerged where the relationship between Predation and Production changed. The tortoise overtook the hare; a virtuous rather than a vicious spiral emerged.

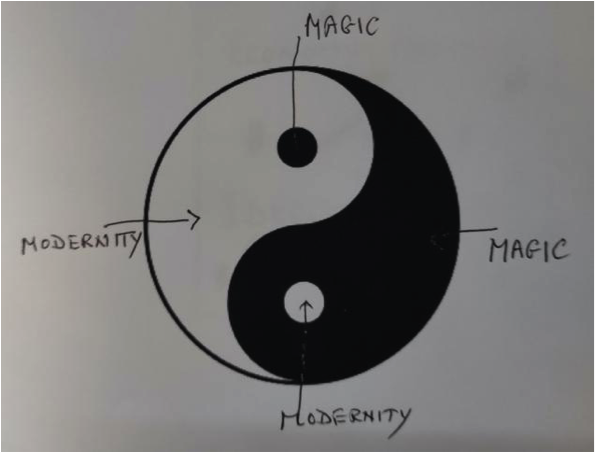

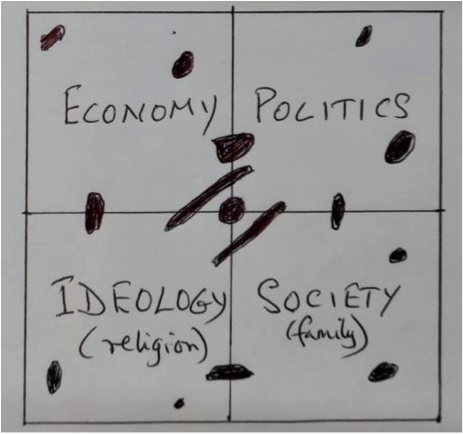

Gellner suggests two main mechanisms whereby this happened. The first was a separation of politics and religion, largely made possible through sectarian squabbles and the growing confrontation of church and state. The second was the growing separation of politics and economics, largely through the growth of wealth brought about by an expanding science and technology.

We can see that Gellner has imported much of the vision of the Enlightenment into late twentieth century discourse. But if we compare his account with that of Montesquieu, Smith and Tocqueville, we can see that, like Fukuzawa, he has also abandoned parts of their analysis. These omitted sections help to round out his interpretation. Part of what is missing can be detected if we look at three assumptions which lie behind his work.

[BURG WARTENSTEIN CONFERENCE #70, July 17 through 25, 1976, Burg Wartenstein Conference Center: The Place of Anthropology Amongst the Sciences: The Soviet and Western View. Front Row: E. Gellner, L. Drobizheva, J. Petrova-Averkieva, C. Humphrey, T. Dragadze, N. Ermakova, V. Basilov, A.I. Pershitz Second Row: J. Goody, V.I. Kozlov, J. Pouillon, L. Krader, M. Fortes, T. Shanin, J. Woodburn, L. Osmundsen Third Row: Y.V. Bromley, Y.I. Semenov, S. Arutiunov, M. Godelier]

The three-stage evolutionary model.

Gellner often used binary models of the oppositional type - for example, us and them, before and after the 'Great Divide'. He often sub-split these to create more complex models, for example a four-way model in Conditions of Liberty and an eight-fold model in Nations and Nationalism. Yet his favourite models for accounting for the curious developments in the west tended to be three-stage, ones.

Quite early in his intellectual life Gellner seems to have convinced himself that three-stage models are the best and that world history can be fitted into such a model. This becomes a dogma in his book on nationalism where he writes that 'mankind has passed through three fundamental stages in its history; the pre-agrarian, the agrarian and the industrial'. Or again he writes, 'my own conception of world history is clear and simple: the three great stages of man, the hunting-gathering, the agrarian and the industrial, determine our problems but not our solution'. Trinitarians who subscribe to the 'elegant and canonical three' stages (Comte, Frazer or Karl Polanyi) are praised. In an interview in 1990 he admitted that 'What is true is that I very much like neat, crisp, models, and try to pursue them, and I would be very uncomfortable if I didn't have one.'

The three-fold model is certainly clear and simple, and it becomes the framework for Plough, Sword and Book, where we are told that 'mankind has passed through three principal stages...' each of which is then briefly characterised. A section on 'Trinitarianism' is included to give support for such an approach.

The difficulty is that such a model, if taken as a universal law of development, does determine not only the problems, but also the nature of the solutions. If we believe with Gellner that there are these three types, each distinct and different, it is indeed difficult to see how the movement from one to the next occurred. Attractive as three-stage theories are, they are probably an 'idol of the mind' in Bacon's sense. They are useful as organizing devices, showing some strong tendencies. But they are not laws of progress. The reaction against such stage theory in the later nineteenth century shows that we should treat them as tendencies, as measures against which we measure actual histories. If reified into necessary sequences and laws of development, they blind us to what actually happened.

[45,500 year old painting at Leang Tedongnge in Sulawesi, Indonesia]

Let us start with the first 'stage'. There is not one generic type of 'hunter-gatherer' society, but numerous types. Gellner is quite aware of the major divisions made namely between immediate-return and delayed-return hunter-gatherers, but there are others. For instance, Australian hunter-gatherers with their elaborate kinship and mythical systems are very different from the cognatic and often mythless African bushmen; or forest-dwellers in the Amazon are enormously different from the Inuit of Canada. From very early on there is enough variation to start mankind moving in all sorts of directions.

In Gellner's scheme there is then a tremendous lumping together of differences in 'Agraria'. Here we have everything from pastoral nomads to densely settled India and China, almost every conceivable kind of kinship system, numerous variations in religious and political organisation. If they are all lumped together or generically similar, it makes the emergence of modern industrial civilisation inexplicable. But once we allow for the possibility that, say, fourteenth-century England, though 'agrarian', was very different from, say, fourteenth-century Poland or Ghana or Peru (or the approximate places where these names would later apply) then it becomes easier to assess what may have happened. The danger of homogenizing the agrarian 'stage' too much can be seen if we examine Gellner's treatment of feudalism. The great divide and the nature of feudalism. Gellner tended to assume, and argue vehemently, that there was a 'great divide' between 'Modern' and 'Pre-modern'. That divide was crossed sometime in the period roughly between 1650 and 1800. Although this framework is again partly implied by the Enlightenment thinkers, it seems likely that by drawing too much on Hume and a simplified version of Smith, and not taking enough account of what Montesquieu and Tocqueville had noted, Gellner found himself in an intellectual cul-de-sac.

Gellner realized that one of the quintessential features of modernity lies in its peculiar blend of status and contract. He believed that before the 'great divide', status had dominated and contract hardly been present. 'Holistic' civilization are dominated by 'status', that is the individual is born into most of her or his relationships and cannot alter them through choice. Such, Gellner believes, was the state of mankind until the last few centuries. This is shown in his summary of the central characteristics of the three major forms of civilization. The hunter gatherer 'was holistic and egalitarian; his successor in complex but static civilizations was indeed both holistic and hierarchical. It is only modern modular man who is both individualistic and egalitarian.'

[Roman de la Rose, M. 948, fol. 12r, 16th century (Morgan Library and Museum, New York)]

Gellner does not realize strongly enough that there was something odd about feudalism, and particularly the form that developed in England. While recognising that the 'relationship between members of various levels in this stratified structure...are...contractual' and 'even affirms a curious free market in loyalty', Gellner still believes that feudalism is 'governed by status and not contract.' Thus he can compare a modern 'open, mobile, growth-oriented, modular social order' to a 'feudal or baroque' one, which is 'absolutist, status-oriented, anti-productive.' It is thus difficult for him to see how strange and powerful feudalism was. If the major transformation which Gellner analyses is rephrased in other terms as the movement from status-based to contract-based societies, or from gemeinschaft to gesellschaft, then according to Gellner, feudal societies are still 'governed by status' and hence on the wrong side of the 'great divide'.

Yet the greatest thinkers on this subject are united in placing feudalism on the 'modern' side of the great divide. Both Montesquieu and Tocqueville and even Adam Smith were aware of the deeply contractual nature of feudalism. Their intellectual descendants, for example Sir Henry Maine and F.W. Maitland re-emphasized this surprising fact. Maitland commented on Maine that: 'the master who taught us that "the movement of the progressive societies has hitherto been a movement from Status to Contract" was quick to add that feudal society was governed by the law of contract'. Maitland added his endorsement: 'there is no paradox here'. In other words that very element of 'progress' and 'growth' which Gellner singles out is present in feudalism. Not only, as he realized, was religion separated from politics, but politics and economics were already in a contractual relationship to each other. We already have the peculiarity he is searching for well before the eighteenth century.

Once we have accepted that the essence of feudalism is its contractual nature, and that this flexibility was widespread in western Europe by the tenth century, the puzzle becomes, as Montesquieu and Tocqueville realized, how to explain the fact that gradually over most of Europe, with the notable exception of England, contract turned into status. Much of their work partially solves Gellner's puzzles by showing that for peculiar reasons a contractual, relatively open, world was preserved within an advancing sea of 'caste' and political absolutism.

The moving spirit.

Gellner's third assumption lies in relation to his prime mover. For Gellner, as we have seen, the external factor which changed the world was the growth of science and technology. He seems to accept that they would grow naturally, as long as the conditions were appropriate. His view is very similar to the simple interpretation of Adam Smith's famous remark that 'Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and the tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.' This is more or less Gellner's assumption. What he has done is to substitute 'science and technology' for Smith's driving mechanism, namely the division of labour. Indeed there is hardly any substitution, for Smith himself envisaged the growth of technology and knowledge as important constituents of the increasing division of labour.If it could indeed be assumed that science and technology will naturally grow if the brakes are taken off, Gellner's solution would be plausible. To use one of his favourite metaphors, with its image of thuggery rather than cars, all that was needed was to 'unthrottle' the system, release the negative forces which prevent 'natural' growth. If one allowed production a free rein, then the rest follows from the 'natural course of things'. Such an assumption means that Gellner's attention is focused on the traps and negative factors.

[Adam Smith]

Yet we know that the puzzle is deeper than this. Possibly peace, easy taxes and good justice, which can be read as short-hand for that separation of politics, religion and economics which are at the heart of modernity, are indeed necessary factors for sustained technological and scientific development. But we know that they are not sufficient. There are many counter-examples through history where, for instance as in Tokugawa Japan, there were long periods of peace, relatively easy taxes and a firm and universal judicial system. Yet technology and science remained almost stationary for two hundred and fifty years. Something more is needed.

To our benefit, and with characteristic wit and width of vision, Ernest Gellner has enumerated some of the conditions for the exit. But by letting his mind rest, by invoking a 'natural tendency' for growth, all else being equal, he has been unable to solve the riddle of modernity.

Optimist or pessimist?

Many paths through time are possible. Ernest Gellner has achieved the difficult goal of remembering that though it seems from our vantage point, looking backwards, that there was some necessity about the path that was taken, this is not the case. We should not lose that insight which was so much more obvious to those who actually lived through the events. We should also not lose his emphasis on the costs as well as the benefits of what has happened. Like Montesquieu, Smith and Tocqueville, and later Weber, Gellner felt a mixture of optimism and pessimism both about the present and the future. When he is optimistic, he quickly balances this by pessimism. Echoing most of the Enlightenment thinkers, he states that 'the two sovereign masters in my philosophy ... were affluence and liberty'. He believed that 'affluence - in the long run' is not 'seriously in doubt', on the other hand 'liberty was the precarious element'. He stressed that the world we live in is not necessarily a pleasant one, even now. 'It has never been my view that this universe is arranged for our convenience, pleasure or edification, and that repellent views may not be true. On the contrary, if anything, I am somewhat inclined to the opposite and pessimistic view, and am rather given to the suspicion that if an idea is repulsive, it is probably correct.

Gellner saw the world as one where consistency is impossible. 'George Orwell was wrong when he ascribed "double think" to totalitarianism. In another, but still relevant sense, the master of doublethink is also essential for liberals, and those who manage liberal societies. They cannot be wholly without beliefs, but they must also know when and how to suspend them, and co-operate with those who hold rival ones.' The 'double-think' which we are forced into, as Smith had seen in the contradiction between private vice and public benefit, or Tocqueville between liberty and equality, is part of the human condition.

[Tocqueville]

In the end, Gellner seems to have marginally preferred our kind of world, and just about believes that it will continue. But it is touch and go. 'On balance, one option - a society with cognitive growth based on roughly atomistic strategy - seems to us superior, for various reasons...this kind of society alone can keep alive the large numbers to which humanity has grown, and thereby avoid a really ferocious struggle for survival amongst us; it alone can keep us at the standard to which we are becoming accustomed; it...probably favours a liberal and tolerant social organisation.' Yet this 'type of society also has many unattractive traits, and its virtues are open to doubt.' Thus, 'On balance, and with misgivings, we opt for it; but there is no question of an elegant, clear-cut choice. We are half pressurised by necessity (fear of famine and so on), half persuaded by a promise of liberal affluence (which we do not fully trust). There it is: lacking better reasons, we'll have to make do with these.' It is hardly a ringing endorsement, but rather two cheers for liberty, wealth and equality.

Further thoughts on Gellner’s problem

Gellner has continued the task of Weber and provided us with some useful tools. Firstly he has re-emphasized the unlikeliness or contingency of what has happened when set against the 'normal' course of human history, both in the past and in the Communist attempt to restore that world. 'We now know that it is indeed possible to escape from the agrarian age of Fear and Faith. We know it because we have indeed escaped from it, though the romantics among us would prefer to say that we were expelled from it. We know it happened, though we do not fully understand how this escape or expulsion came about.' He has also emphasized that understanding this expulsion or escape is the central problem of the historical and social sciences. 'How did we escape this condition, for escape we did? This is the single most important problem in theoretical sociology, and it is the question which largely engendered sociology as a systematic inquiry.' He has suggested that the key to understand what has happened lies not in particular forces in themselves, but in the dynamic tensions between them.

This is a structural approach which looks at the relations rather than the things, and again it is in the Weberian tradition. It is to separation, balance, opposition, contradiction, tension that we need to look if we are to understand more deeply these strange events. Thus in the relations of polity and economy 'What is important is not merely the separation of the social and die economic, but the balance of power between the two.' Gellner's idea of mix, separation and tension is well expressed in his core definition of the Civil Society. 'It is a society in which polity and economy are distinct, where polity is instrumental but can and does check extremes of individual interest, but where the state in turn is checked by institutions with an economic base; it relies on economic growth which, by requiring cognitive growth, makes ideological monopoly impossible.' This explains why such societies are characterized by compromise, inconsistency, double think, for ‘...a free order is based in the end not on true and firm convictions, but on doubt, compromise and doublethink.' Yeats' version of a world where the 'centre cannot hold' and 'mere anarchy is loosed upon the world', fits perfectly here. For what Yeats saw that the 'best lack all conviction', and the worst are 'full of passionate intensity’. This is the perennial condition of liberal democracies, but usually the convictionless 'best’ outnumber the enthusiastic fanatics and this, plus James Scot's 'dull compulsions of economic life' prevent things falling apart.

The difficulty, of course, is how to test the theories, for when dealing with a 'unique' event, it is impossible either to re-do die experiment or to compare it to anything. This was Weber's problem, as Gellner notes when discussing Weber’s theory of the role of religion in the rise of capitalism. The combination of Protestantism and Catholicism, Gellner suggests Weber believed, lay at the heart of modernity. ' It was this mix which by some strange internal chemistry engendered the modern world. Whether only it could have done so, as a very great sociologist seemed to suggest, we shall probably never know: we cannot re-run the experiment in order to find, out.'

The difficulty is very great 'if we possess one instance only of a particular transition. Too many factors are present for us to be able to single out the crucial ones.' There is some new hope, however. Considering the causes of modernity 'It will be a long time before we can fully sort this out: even the 'Western' transformation is far from played out, and the others are in relatively early stages. Nature, or history, has not been too kind in providing neat experimental situations, adequate premises for Arguments by Elimination. Nevertheless, we can make some headway in this direction.' He believed that hope lay in what was beginning to happen elsewhere in the world. 'When industrialisation had happened only once, those who had been through it tended to confuse it with what may have been accidental or once-only concomitants of its first occurrence. Now, the repetitions provided by new combinations of circumstances, and the attempt to understand and facilitate the process in new places, also throws light on its earlier occurrence in the West.'

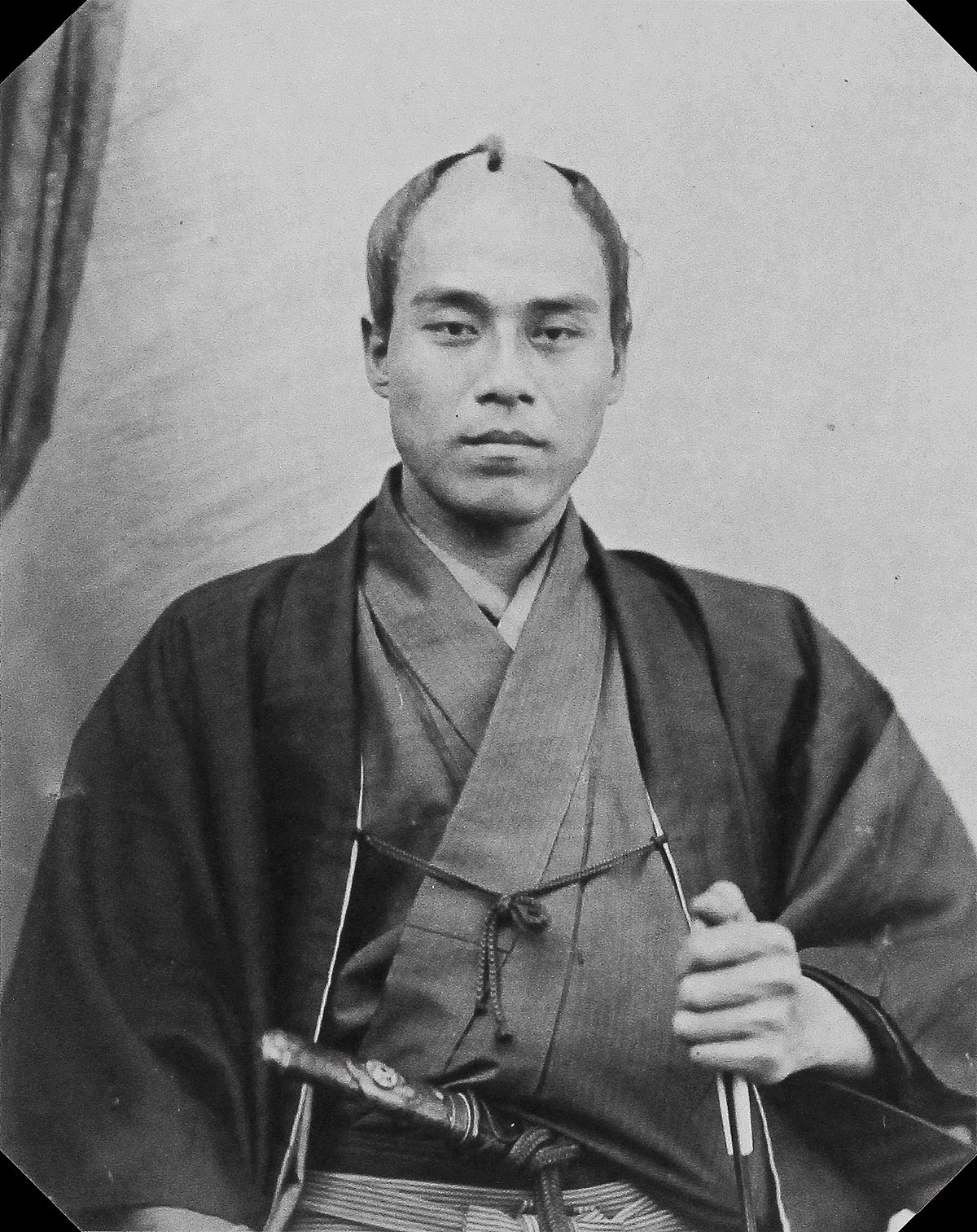

[Japanese and European knights: Left: Library of Congress, Right: Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Thus we should look elsewhere. 'The real intellectual significance of the political life of "underdeveloped" countries for the West is that, for the first time, we now possess anything like a valid mirror for self-understanding. As long as only one instance of the great transition was available, it was in practice almost impossible to distinguish the characteristics of the West, which were not essential to the transition, from, those which were essential, and so forth.' This was written, as stated, over thirty years ago before the development of industrialization in many parts of the world, and in particular the dramatic development in Japan and other parts of East Asia had become apparent. It is a pity that for various reasons Gellner never followed this up. By basing his life’s work on Islam and the Soviet Union he strengthened that part of it devoted, to understanding the difficulty of the escape and the importance of separating spheres. Yet he was never able to use the Asian material to test the hypotheses. Weber was too early to do so: Gellner did not have the inclination.

[Fukuzawa Yukichi, the great anthropologist of Japanese modernity]

*

Gellner realized, that one of the quintessential features of modernity lies in its peculiar blend of status and contract, which comes very close to a discussion of what his friend Ronald Dore calls 'flexible rigidities'. We tend to be somewhat misled by the assertion that 'In Europe, the contrast between community and society is one between the past and the present: we move from community to society. In Islam, these two were ever present, synchronic: community at the margins, society at the centre.' In fact, as Gellner shows, modern civilization is also based on the co-existence of both principles. A modern Civil Society has to have at least, temporary, flexible, communities, as well as individual choices. 'Civil Society is a cluster of institutions and associations strong enough to prevent tyranny, but which are, none the less, entered and left freely, rather than imposed by birth or sustained by awesome ritual.'

In a central passage he points out the tensions, peculiarities and contradictions. 'Modular man is capable of combining into effective associations and institutions, 'without' these being total, many-stranded, underwritten by ritual and made stable through being linked, to a whole inside set of relationships, all of these being tied in with each other and so immobilized. He can combine into specific-purpose, 'ad-hoc' limited association, without binding himself by some blood ritual.' This is the peculiarity, the existence of a combination of all those nineteenth century dichotomies - Community and Association (Tonnies), Status and Contract (Maine), Mechanical and Organic solidarity (Durkheim) and so on.

There is a partial, but only a partial movement along these dichotomies. 'It is 'this' which makes Civil Society; the forging of links which are effective even though they are flexible, specific, instrumental. It does depend on a move from Status to Contract: it means that men honour contracts even when they are not linked, to ritualized status and group membership. Society is still a structure, it is not atomized, helpless and supine, and yet the structure is readily adjustable and responds to rational criteria of improvement.' By some miracle, 'these highly specific, unsanctified, instrumental, revocable links or bonds are effective! The associations of modular man can be effective without being rigid!' The university College or good business firm or orchestra, or games team is an example of all of this. And, if he had studied it, Gellner would have found that this was the most powerful feature of Japanese civilization. The ability to hold people together and yet give them freedom is very unusual.

*

Now this peculiar position of balance of institutions or interests, of moderation, caution, tolerance, lack of passionate intensity, of trust and single-minded rationality, is another characterisation of 'modernity'. By Gellner's three-fold model it is entirely antithetical to the major features of the hunter-gatherer and agrarian stages. Tribal societies are not based on Hobbesian individualism, but on embedded segmentary structures where kinship dominates all. Agrarian civilisations are again based on status, but this time the status of a hierarchy of religious and political power.

In fact, once we drop the three-fold model and simple characterisation, it is possible to find almost perfect anticipation of much of this characterisation in all 'stages' of human civilisation. It has long been noted that African hunter-gatherers, and hunter-gatherers in general, are curiously 'modern' in many ways. Though they lacked the technology, literacy and so on, they often seem to have had the essential quality that nothing dominated ('free' individuals were not slaves to one institution) - religion, polity, economy or even kinship. From the start, then, it may be that 'modernity' existed a very long time ago.

The normal course of affairs was for this ’modernity' to be crushed during the long intervening years, as Gellner points out. As populations grew more dense and wealth was congealed, hierarchies emerged and mankind became dominated by religious or political institutions or, usually, a mixture of the two. This 'ancien regime’ world was to be found in most of Asia or pre-Revolutionary Europe or South America. It seemed a necessary ‘stage’ in the famed transition between tribal and 'modern' societies. Its social concomitant was peasantry.Yet, apart from our own imposed model-building tendencies, there is no need to believe that this was the only and necessary course. It is quite conceivable that the path has varied all over the world. In western Europe, for instance, it could be argued that after the fall of the Roman Empire, there was a strange mixture of several elements. The survival of traces of Romanism, the contractual political system of Germanic feudalism, the ascetic and individualistic (and, according to Gellner, modest) religion of Christianity, the non-segmentary kinship system combined to produce, over the centuries between about (the fifth and the eleventh, a new and potentially 'modern' system in terms of the division of spheres outlined above.

Put in another way, the secret must lie in the properties of the four main institutions, all of which must have a non-exclusive and limited character. This seems to have been the case. Christianity, especially in its heretical forms and later in Protestantism, was not too deeply involved in this world, allowing people to render to Caesar that which was Caesar’s. The bilateral kinship system cannot form the basis of the society since it built up no discrete political or social groupings. The political system, based on the contractual feudal system, was powerful enough to guarantee some order, but was always held in check by the countervailing devolution of power that is a necessary feature of feudalism. The ruler is the first among equals, unable to rule without consent, a limited monarch. The economy in this technologically backward and varied landscape was not strong enough and produced too little wealth, to allow it to dominate.During the centuries after the eleventh, of course, much of this changed and the widespread tendencies which have been found in older civilisations, such as those in India, South East Asia and China, manifested themselves. Over much of central, eastern and southern Europe, a 'caste-like' society arose with hereditary nobility, a King above the Law, a Church in the alliance with the state. The usual re-confusion of economics, moral, political, social and religious spheres occurred. How this happened, is brilliantly described by Guizot, De Tocqueville’s teacher and mentor.

[François Guizot by Jehan Georges Vibert]

[François Guizot by Jehan Georges Vibert]

Yet for reasons which are strictly historical and accidental, (this widespread tendency did not occur in northern Europe to the same extent, in particular in England much of the 'modernity', in the sense of balance of forces, implicit over much of Europe in the tenth century survived. It continued and provided the balanced platform for the emergence of a new technology (industrialism) and society (urbanism). There was certainly no inevitability about this. And it is indeed extremely unlikely and unusual. But nor is there any particular mystery. By failing to gravitate towards absolutism, inquisition of familism, part of northern Europe preserved a balance which allowed free-floating individuals to make themselves wealthier in peace, within a secure framework. This was what the Pilgrims took to America.