Global Justice, Trade and Philosophy ... and Nietzsche Too

Interview by Richard Marshall.

'One central term for me is that of a ground of justice. The grounds of justice are the features of the population (exclusively held) that make it the case that the principles of distributive justice hold within that population. In other words, these are the features that make the notion of distributive justice applicable within that population.'

' So pluralist internationalism recognizes five different grounds of justice: shared membership in a state; common humanity; humanity’s collective ownership of the earth; membership in the world society (or, as I used to call it, in the global political and economic order); and subjection to the global trade regime. Each of these has different principles of distributive justice associated with it. '

'What is indeed rather distinctive about my approach is the significance I give to humanity’s collective ownership of the earth. Thereby I revitalize and secularize an approach dominant in the 17thcentury that has never again reached as much prominence, and that has largely (though not entirely) dropped out of sight since the Rawlsian Renaissance of political philosophy.'

'Would we actually be better off without states? This question turns on counter-factuals that we really do not know how to assess. Sometimes cosmopolitans talk as if we hung on to states only out of pragmatic consideration. But the truth is that we have no alternative to a system of states that we understand sufficiently well for it to be action-guiding in terms of where we go from here, this point in history.'

' I take the concept of human rights to refer to rights with regard to the organization of society that are invariant with respect to local conventions, institutions, culture, or religion. Human rights language focuses on abuse committed by those in authority: of otherwise identical acts, only one might violate human rights.'

'Doing justice to such a complex notion as justice (pardon the pun) requires different types of inquiry. It requires analytical inquiry, to make sure what is said meets standards of rigor and precision. But it also requires historical and comparative inquiry, since the importance of “justice” is such that one can’t just make one’s own stipulations about what the term is all about and start making arguments around that term, but should pay close attention to how the term has been developed before.'

'Trade remains elusive and profoundly difficult for philosophical thought – which explains to a large extent why trade has been a neglected topic but it is also precisely why it’s such an important and fertile domain for philosophical inquiry.'

'Thinking about German Orientierungskultur, and thus about German culture as something that orients people in Germany, allows for a credible articulation of a liberal ideal for Germany while also addressing worries about alienation as they arise in a globalizing world.'

' Nietzsche is generally a fighter against prejudice wherever he sees it. Many philosophers would think that is precisely the route towards egalitarian commitments. But Nietzsche takes a decidedly hierarchical, aristocratic approach to social organization. Therefore he becomes the nemesis of those of us who see ourselves working on a kind of egalitarian plateau (including myself!).'

Mathias Risse works mostly in social and political philosophy and in ethics. His primary research areas are contemporary political philosophy (in particular questions of international justice, distributive justice, and property) and decision theory (in particular, rationality and fairness in group decision making, an area sometimes called analytical social philosophy.) Here he discusses global justice, the ground of justice, Globalists and Statists, pluralist internationalism, the five grounds of justice in pluralist internationalism, humantity's common ownership, whether we're better at small scale rather than grand style theorising in this area, whether we'd be better off without states, human rights, trade and justice, the link between his view of global justice and ancient approaches to justice, and finally issues arising from immigration in Germany.

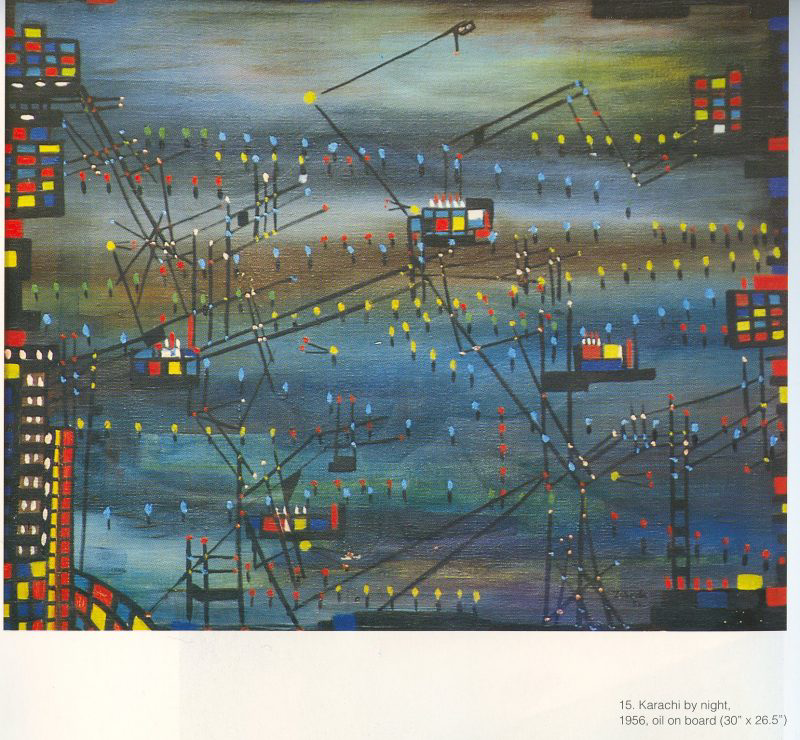

(Art by Zubeida Agha)

3:AM: What made you become a philosopher?

Mathias Risse: I grew up in Westphalia, in rural Germany, in a working-class family, and had little sense of what philosophy was while growing up. Educational reforms in the 1970s made it possible for people of my background to go to Gymnasium, the type of high school that qualifies for entrance to universities. So I went to Gymnasium (though the elementary school principal had misgivings about it), and ended up being a good student, but with little sense of where this was all supposed to lead. I had no professional role models nearby, so things had to take their course. I enjoyed reading all sorts of things, and was even regarded with some suspicion by the librarian on the upper floor of the archiepiscopal library (Catholic area) – though that library most certainly didn’t have anything unsuitable for kids of any age. On several occasions, over the years, I found myself in situations where something I said prompted some adult to say that something about my comment was “philosophical.” That’s how that word made an appearance in my life. One such occasion was in math class, when at 16 or so, I was somewhat overwhelmed by the definition of a circle, the set of all points equidistant from another, in terms of my, or anybody else’s, inability ever to draw something like that with the kind of accuracy implied by what it meant to be a “point.” I started reading books with “philosophy” in the title, though initially mostly histories. I also attended an information session at the University of Paderborn (my home town), around 1989. The professor who held it (Holm Tetens, who later went to the TU Berlin) mentioned that he himself had attended a session with a guidance counselor many years earlier, and was told then to mend his ways when he said he wanted to become a professor of philosophy. Pursuing that career then seemed like a crazy but not utterly pointless fantasy.

Eventually decision time came – what to study. In hindsight it was amazingly naïve to study philosophy with the goal of becoming a professor of it with what little knowledge and understanding I had. To be prudent I decided to also study mathematics. I figured as a mathematician I’d not be unemployed. And as bizarre as it sounds, I also liked about math that it never came easily to me. So it was a challenge, and I liked that. I realize this all sounds rather unreal: but in truth, had I followed the advice of smart people around me I would probably have studied law. Instead, I decided to enroll in pursuit of a master’s degree in both philosophy and mathematics. For reasons concerning the organization of the German university system at the time, that turned out to be difficult. The University of Bielefeld would let me enroll in pursuit of both degrees (being a reform university, they let people enroll for just about any combinations). So I went there.

I had also been politically active, becoming a member of a political party (the FDP, Freie Demokratische Partei, seeing myself on the left wing of that party, which made me more a liberal in the American than the German sense). I even ran for (a minor) office and had functions in the party, considering this a possible career path. Eventually I discovered social choice theory. I had started attending seminars offered by a private educational organization in the political domain and started talking to a universal spirit called Daniel Diermeier who had done the rather daring step (by standards of that time) to study in the US for more than just an exchange semester. He told me about the work of people like Ken Arrow and Amartya Sen, and I saw all my philosophical, mathematical and political interests somehow coming together in a field like social choice and game theory. (Incidentally, Daniel, who as turns out now is the provost of the University of Chicago, also talked to me about career paths in American academia, and I distinctly remember a statement from him about distant and mystical Harvard: that people hired for faculty positions there would normally end up getting tenure, but normally not at Harvard. Not sure why we would have talked about that then, but it got stuck in my mind.)

I was also very lucky with some teachers at Bielefeld, especially Wolfgang Spohn and Ruediger Bittner. Both are among the most gifted German philosophers. Spohn also helped me become a visiting student at the University of Pittsburgh (for which a personal encounter with John Earman was crucial, who invited me officially), where I got a sense of American academia. And that was a revelation experience. At Pittsburgh I encountered a department consisting of about 20 faculty and 40 graduate students who created a critical mass for treating philosophy as a living research discipline. Courses were taught at a very high level because there were enough students there who would take such courses. I learned a tremendous amount especially from their graduate-level core courses (taught by Kurt Baier, Wesley Salmon, John McDowell and others). Philosophy also became tractable as a career in the US in ways in which it really wasn’t in Germany since there was a regular job market that one would enter at the end of one’s PhD studies. One would then become an assistant professor, rather than, as in Germany, an assistant to a professor, a position that had much less potential to lead to long-term employment.

And so it had all gradually fallen into place. I studied some more game theory at Pittsburgh (with Al Roth), then at the Hebrew University (with Robert Aumann), and then ended up a PhD student in philosophy at Princeton, working with decision theorist Dick Jeffrey. The decision to say in the US longer, or generally to be away from home longer, had been rather agonizing, but I was very fortunate to be admitted to that program. Jeffrey recently had himself gotten interested in social choice and game theory and encouraged doing projects together, a very unusual experience for a first-year graduate student. Overall, the Princeton department (where I was 1995-2000) was a great place for me: most students there did M&E or philosophy of mind. As somebody with a range of interests outside of that I had ready access to a range of wonderful faculty who were specialized in that mainstream, including Alexander Nehamas, Harry Frankfurt and Gopal Sreenivasan. Eventually I wrote a dissertation under Jeffrey’s supervision and that of Paul Benacerraf (who had told me once that, whatever I ended up doing, he wanted to be the second advisor – go figure). I wrote that dissertation on philosophical (and some mathematical) questions of various sorts that arise about collective choice. I got my first job at Yale in 2000, got interested in questions of global justice (triggered by some disagreements with Thomas Pogge’s pathbreaking work in that domain), and from there moved to the Harvard Kennedy School in 2002. And that’s a good place to be for somebody who ended up at this intersection of philosophy, social science and politics. It is also true, though, that somebody with this kind of profile seems to carry a rather heavy burden of proof in all directions: too often still philosophers only have those other philosophers on their radar who are actually based in a philosophy department (all academic fields find ways of being parochial), and at any professional school philosophers have to explain their relevance more than others do. But I suppose all that is also rather healthy, intellectually speaking.

3:AM: You’re an expert on global justice. Global justice usually contrasts cosmopolitans with a statist view of justice so perhaps we can start by asking you to sketch out the main ideas of these two views?

MR: I actually try to avoid using the term “cosmopolitanism” in global-justice debates. The reason is that it has become too much of an all-purpose term, with cosmopolitans appearing to share no more than a commitment to some form of universal moral equality that can be rather weak in nature. I like to use somewhat different vocabulary here. But the gist of it is that the standard views in the debate about global justice disagree about whether principles of distributive justice only apply within states or whether they apply to everybody. However, to make it easier later to introduce my competing view, let me introduce this different vocabulary.

One central term for me is that of a ground of justice. The grounds of justice are the features of the population (exclusively held) that make it the case that the principles of distributive justice hold within that population. In other words, these are the features that make the notion of distributive justice applicable within that population. Typically philosophers would say there is oneground of justice, and then views differ about what that ground is. Most fundamentally, there are two families of views here. “Relationists” about the grounds of justice apply principles of justice only among individuals who stand in a certain essentially practice-mediated relation; “non-relationists” account for principles of justice without recourse to such relations. A reference to practices keeps nonrelationism from collapsing into relationism. The relation of “being within 100,000 kilometers of each other” is not essentially practice-mediated, nor is, more relevantly, that of “being a fellow human.”

Relationists may hold a range of views about the nature of the relevant relations, and they may think there is only one relational ground or several. Relationists are motivated by concerns about “relevance,” the moral relevance of practices in which certain individuals stand. Such practices may include not only those that individuals chose to adopt but also some in which they have never chosen to participate. Nonrelationists deny that the truth about justice depends on relations. They think principles of justice depend on features that are shared by all members of the global population, independent of whatever relations they happen to be in. Rather than focusing on relevance, nonrelationists seek to avoid the “arbitrariness” of restricting justice to regulating practices. Globalization may have drawn our attention to the fact that justice applies globally, say the nonrelationists, but in fact it always did

“Globalists” are relationists who think the relevant relation holds among all human beings; “statists” think it holds among those who share a state. Globalists think there is only one relevant relation, and that relation holds among all human beings in virtue of there being a global order. Statists, too, think there is only one relevant relation, and think that relation holds (only) among individuals who share membership in a state. Statists endorse what I call the normative peculiarityof the state; globalists and nonrelationists deny it. However, nonrelationists agree with statists and globalists that there is only one ground of justice. Offering a theory of justice then means to assess what the uniquely determined ground of justice is and then to assess what principles apply to relevant populations. And one way of connecting to the notion of cosmopolitanism here is to say that cosmopolitans in the distributive-justice debate are either globalists or non-relationists.

3:AM: You approach global justice differently with pluralist internationalism. Firstly, why aren’t you convinced by either cosmopolitans nor statists?

MR: Roughly speaking, I think statism, globalism and non-relationism are not differentiated enough, each in its own way. Suppose I am a statist. Statists owe some kind of account of what is so special about shared membership in states that renders the particular demanding considerations of distributive justice applicable within states, but not outside. Typically statists do this by explaining how people who share a state either cooperate in a particularly intense way, or else they are jointly subject to a coercive system that has particular features. But we now live in a rather intensely interconnected world where states coordinate many things through international organizations and decisions made within such organizations (think of the WTO) matter greatly. The kinds of cooperation and coerciveness characteristic of such organizations connect individuals in much looser ways than states do – but to say that considerations of distributive justice just cease to apply outside of states does not seem to live up to the realities of our interconnected world.

The two “cosmopolitan” views have the opposite problem. The moral significance of what people do together in states is not such that nothing that happens outside of them should be discussed in terms of distributive justice; but nor should it just be irrelevant from that standpoint, as it ultimately would be if globalists or non-relationists were correct. More nuance is needed.

3:AM: So what are the advantages of the approach you take with pluralist internationalism over these two rivals?

MR: Now, of course, statists could find ways of recognizing the moral relevance of what is taking place outside of states, and the cosmopolitan views could try to find non-ideal-theory takes on the significance of states. But perhaps a better way forward is to give up on the idea of there being a just oneground of justice. We should consider the possibility that there is no deep conflict between relationism and nonrelationism. Perhaps advocates have respectively overemphasized facets of an overall plausible theory that recognizes both relationist and nonrelationist grounds. Integrating relationist grounds into a theory of justice pays homage to the idea that individuals find themselves in, or join, associations and that membership in some of them generates duties. Integrating nonrelationist grounds means taking seriously the idea that some duties of justice do not depend on the existence of associations. One obvious non-relational ground to add is common humanity. So in this way we get a range of views that recognize multiple grounds of justice, and these views might disagree about the particular list of grounds they propose and what principles of justice they think are associated with these grounds. My own view, pluralist internationalism, is one member of this family of views. The use of the term “internationalism” for this position acknowledges the applicability of principles of justice outside ofand among(“inter”) states – but that also means states continue to have a fundamental importance. And the term “pluralist” here makes clear that we are indeed talking about a plurality of grounds.

So the key move here is indeed to recognize a plurality of grounds of justice. The basic motivation for that is the crudeness involved in the various one-ground views. And that is not just a semantic matter: The reason we care about justice is that it makes demands of highest stringency – and there is quite a range of those that need to be brought under a unified though differentiated umbrella theory. And then of course all the action is in the work needed to pull this off – both foundational work and the insights it generates for applied questions.

(Art by Zubeida Agha)

3:AM: Are redistribution principles applied within a country the same as those used to apply to those outside according to your approach – and what are these principles and where do they come from?

MR: So pluralist internationalism recognizes five different grounds of justice: shared membership in a state; common humanity; humanity’s collective ownership of the earth; membership in the world society (or, as I used to call it, in the global political and economic order); and subjection to the global trade regime. Each of these has different principles of distributive justice associated with it. For each ground a case would have to be made why it should be included in this list (there’s after all no magic to the number 5), and a constructive argument must be made about the content of the distributive principle. “Constructive” – in the sense that detailed work with the features of the ground is required to make such a case. As far as shared membership in states is concerned, the principles are the Rawlsian principles (or something like them). The kind of work required to show is the kind of work Rawls already did – to explain why the distribuendum in this case should be social primary goods, and why they should be shared out the way his principles stipulate rather than as prescribed by a short list of competitors.

And so it would go ground by ground. In the case of shared ownership of the earth, one first needs to argue that the earth as humanity’s habitat is sufficiently important, and of the right sort, to be included in the list and then look at a range of proposals that have been made for how to think about the resources and spaces of the earth. They need to be compared in terms of their relative merits. As far as trade is concerned, the key to the relevant distributive principle is absence of exploitation, and then of course all the action lies in working out a suitable notion of exploitation and answering a range of questions about it (including the question of why trade justice should be conceived in such terms in the first place). In my book On Global Justice I didn’t say enough about trade, and so I always knew that more work was needed in that domain. That work is now done in my forthcoming On Trade Justice: A Philosophical Plea for a New Global Deal, co-authored with Gabriel Wollner. If all goes well, that book will be out later this year, with Oxford. This kind of work then delivers this list of principles associated with different grounds:

1 Shared membership in a state: 1. Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all. 2. Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity, and (b) of the greatest benefit to the least advantaged.

2 Common humanity: The distribution in the global population of the things to which human rights (understood as rights needed to protect the distinctively human life) generate entitlements is just only if everyone has enough of them to lead a distinctively human life (and thus if those rights are satisfied).

3 Collective ownership:The distribution of original resources and spaces of the earth among the global population is just only if everyone has the opportunity to use them to satisfy their basic needs, or otherwise lives under a property arrangement that provides the opportunity to satisfy basic needs.

4 Membership in the world society: The distribution in the global population of the things to which human rights (understood as membership rights) generate entitlements is just only if everyone has enough of them for these rights to be realized.

5 Trade: The distribution of gains from trade among states is just only if they have not arisen from exploitation involving the basic rules of the international trade regime.

3:AM: You talk about ‘humanity’s common ownership’ as being an important ground for thinking about issues such as immigration, obligations to future generations and obligations linked to climate change. So how are we to understand this common ownership and how does it help in the way you say it does?

MR: What is indeed rather distinctive about my approach is the significance I give to humanity’s collective ownership of the earth. Thereby I revitalize and secularize an approach dominant in the 17thcentury that has never again reached as much prominence, and that has largely (though not entirely) dropped out of sight since the Rawlsian Renaissance of political philosophy. Suppose the US population shrank to two, capable, however, of controlling borders through electronic equipment. Surely they should permit immigration. If so, we should theorize about the space humanity jointly inhabits, and about what entitlements there can be to parts of it. Such theorizing takes us to a suitable notion of collective ownership of the earth. In the 17thcentury, the motivation for this approach was obvious: the Bible states that God gave the earth to humankind in common.

Many questions could be addressed through an interpretation of that gift, such as concerns about the possibility of owning the sea and the conditions under which territory could legitimately be claimed. Philosophers such as Hugo Grotius, John Locke, and Samuel Pufendorf saw questions of collective ownership as central to their work. This approach is also present in international law, where for about forty years the term “common heritage of mankind” has been applied to the high seas, the ocean floor, Antarctica, and Outer Space. Central questions include how to make sense of this ownership status without recourse to a divine gift, and how to select the philosophically preferred one from among different versions of it. Immigration is one topic to which this approach applies. Less obvious ones include human rights, as well as obligations towards future generations and obligations arising from climate change. At this stage, not only do we face problems of global reach, but humanity as a whole confronts problems that have put our planet as such in peril. It is therefore only appropriate to find a suitable place in moral and political philosophy for theorizing about all human beings’ symmetrical claims to the earth.

Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth was the pivotal idea of the political philosophy of the 17thcentury. European expansionism had come into its own, so questions of global reach entered political thought and needed to be addressed from a standpoint that was nonparochial (not essentially partial to one of their viewpoints) as far as European powers were concerned. (The ensuing debates only included intellectuals from the European context since the point was to justify the details of colonial expansion). At the same time, appealing to God’s gift of the earth—as reported in the Old Testament—was as secure a starting point as those religiously troubled times permitted. Although that debate took the biblical standpoint that God had giventhe earth to humankind, some protagonists, such as Grotius and Locke, thought this matter was also plain enough for reason alone to grasp. And indeed, the view that the earth originally belongs to humankind collectively is plausible without religious input, and outside of that ugly colonial context in which it mattered in the 17thcentury. We have much to gain from revitalizing this idea, mostly because it makes it possible to underscore the idea that there are resources and spaces that we all need for anything we do but that no human has done any more than any other to put there.

One might of course wonder whether ownership aptly captures our relationship to the natural world. Walt Whitman praised animals, by way of contrast with humans, by emphasizing that “not one is demented with the mania of owning things” (section 32 of “Song of Myself”). Yet collective ownership is a view about the relationship among human beings that can readily integrate plausible accounts of environmental values. Collective ownership is a view designed to sort out claims humans have against each other once those environmental values are respected. While the civil law often permits us to destroy objects, collective ownership does not per se entail the permissibility of wanton destruction, nor does it commit us to ascribing merely instrumental value to nature.

Valuing nature intrinsically, as sublime or awesome, as providing a context where human life obtains meaning, and even as sacred, is consistent with my view. The idea that humanity owns the earth has done its share in the history of human chauvinism. But my secularized understanding of collective ownership does not presuppose the arrogance associated with a reading of the Bible that subjects the creation to the human will, an attitude that emerges, for instance, in Calvin’s view that God took six days to create the world in order to demonstrate to human beings that everything was prepared for them. In that way my approach differs from its 17thcentury predecessors many of whose advocates accepted this stance. Generally in this domain I endorse what Bernard Williams called enlightened anthropocentrism, the view that all values must be values to human beings and on a human scale, which, however, does not mean the range of such values is exhausted by instrumental values or values of human flourishing.

3:AM: Are we at the moment in a better situation to work on sub-topics within the domain of global justice than actually develop an overview of what global justice actually is in detail?

MR: I think a lot of people think that. There is of course a long-standing position in philosophy that shies away from “big words” and grand-scale theorizing and the instead focuses on either the kind of theorizing one can still do without big words or else focuses very much on concrete scenarios. So philosophers who hold such views would not smile on the global-justice literature. But my own stance on these matters is (unsurprisingly) that we can indeed make sense of questions about global justice, in the sense that there is meaningful disagreement about the various foundational positions that I sketched earlier. And then there are also those philosophers who do not disagree that the global-justice debate is meaningful but who think that progress on more specific questions is more easily made if we suspend the big-picture questions.

Recently such a move was made in Peter Dietsch’s excellent work on tax evasion and tax competition (see his book Catching Capital). But, as Marco Meyer and I argue in a review of that work in the Notre Dame Review of Philosophical Books, one cannot really escape underlying questions about global justice for more specific questions such as those that arise about taxation. After all, matters of global justice are fundamentally about obligations across borders, which are foundational questions that are impossible to avoid in any more applied debates about cross-border ethics. The dispute with Dietsch, by the way, is going into another round through the publication of two essays on tax competition in the Journal of Political Philosophy, one by Marco Meyer and myself and the other by Peter Dietsch and Thomas Rixen.

But all that said, what I think has been happening in the global-justice domain is that people have been focusing more on specific questions. When I published On Global Justice in 2012, that book came on the tail-end of a lot of large-scale theoretical attempts to capture distributive justice at the global level. What my work added to that, I think, was a rather comprehensive articulation of a pluralist standpoint re. grounds of justice. But as of today that kind of work is of course in place, creating opportunities for people to turn to more issue-specific matters, such as taxation, trade and many others. That’s certainly a very positive trend. But we still need the big-picture views in the background.

3:AM: Is a key problem that we organize ourselves into states – would things be better if we didn’t have states? Or is our global interdependence such that we’re already approaching a time when to consider states as independent entities is a fallacy?

MR: States get a lot of bad press in philosophical and other journals, and rightly so – states make wars, and even in times of peace a world of states looks like a world organized to maximize mutual indifference. And of course abusive states prey on their own people (a rather common phenomenon). At the same time, states also do a lot of good since where they function well they organize social services, maintain infrastructure, provide protection, etc. Even now that the world has gone through all this political and economic globalization states remain by far the most powerful entities – even where states are deeply embedded into international organizations it’s with states that military and financial power remains. States might eventually wither away, yes, but we are nowhere near that stage. Our world of states is pretty robust and enduring, the complexities of interconnectedness notwithstanding.

Would we actually be better off without states? This question turns on counter-factuals that we really do not know how to assess. Sometimes cosmopolitans talk as if we hung on to states only out of pragmatic consideration. But the truth is that we have no alternative to a system of states that we understand sufficiently well for it to be action-guiding in terms of where we go from here, this point in history. But since we do not have that, the thought that it is merely for fear of ensuing political chaos that we should hang on to states understates the intellectual support for states. There may well remain nagging doubts about whether there ought to be states at all. Nevertheless, morally rather than merely pragmatically, we ought not to abandon states now. In conjunction with the fact that states solve public-goods problems, the absence of action-guiding alternatives turns pragmatic acceptance into qualified moral endorsement.

The point is not merely that we should not immediately seek to create a world without the kind of power centers constitutive of states. Rather, we should not now actively aim to create it at all, even step by step. After all, we do not understand well enough what such a world would be like. Again, perhaps states will wither away, and we must then reconsider what counts as realistically utopian. But saying that is very different from now urging reforms designed to create a world with some kind of global demos (which may or may not be organized in a single world state).

3:AM: How do you think we should understand and develop a theory of human rights given your theory of pluralist internationalism?

MR: I take the concept of human rights to refer to rights with regard to the organization of society that are invariant with respect to local conventions, institutions, culture, or religion. Human rights language focuses on abuse committed by those in authority: of otherwise identical acts, only one might violate human rights. There is a difference, say, between thefts committed by petty criminals and thefts that are part of abusive patterns of government behavior or expressions of socially entrenched oppression. A host of questions arises. Why would we hold such rights? Are there human features on which they are based? What ought to be their function in the world? What rights arise in this way? A conception of human rights provides answers. It consists of four elements: a list of such rights; an account of what features make individuals rights holders; an account of why that list has that composition, a principle or process that generates that list; and an account of who must do what to realize rights. Using these distinctions one could classify much recent philosophical work on human rights.

According to orthodox conceptions, human rights protect the distinctively human life. Much has to be said about what that life is, what protection in terms of rights amounts to, and why it is required. What matters now is merely that for orthodox conceptions human rights are natural rights. For natural rights, the range of duty-bearers is not restricted by transactions or membership in associations. Therefore all human beings are potential duty-bearers: protecting the distinctively human life is a global responsibility. The global order is the obvious addressee for these rights. But we may ask: how elsecould rights become a global responsibility? Instead of thinking of human rights exclusively as rights individuals hold in virtue of being human, we could understand them as rights for which there is a genuinely global responsibility – that is, as membership rights in the global order. Or that is, in recent years I have thought about human rights as membership rights in world society, which is a sociological term by way of contrast with “global order,” which is a political-scientific term. But I set that aside here. The point for present purposes is that membership in the world society is itself a ground of justice, which is why above I already included the following in the list of principles of justice:

Membership in the world society: The distribution in the global population of the things to which human rights (understood as membership rights) generate entitlements is just only if everyone has enough of them for these rights to be realized.

So in this manner the human-right framework is integrated into the global-distributive-justice framework. Human rights thus understood are rights that are indeed accompanied by genuinely global responsibilities, rather than rights people would hold everywhere but accompanied only by respectively local responsibilities. Rights of that second sort are rights of citizens and thus matters of social justice. Membership rights in the global order/the world society derive from different sources, one being the distinctively human life. But if there are other ways of deriving rights that entail a global responsibility, that kind of life becomes one in several sources of membership rights. Orthodox conceptions do not appeal to contingencies other than laws of nature, facts about human nature, or the fact that certain beings are human. A conception in terms of membership in the global order, by recognizing other sources, uses contingent facts more freely, enlisting features of a contingent but abiding order.

One additional source is enlightened self-interest. For this source, one first shows that certain matters give rise to moral rights domestically. A self-interest argument then shows why this matter is globally relevant. Preserving the peace may require that authority is exercised in certain ways, perhaps because unchecked governments will create negative externalities. Concerns about peace, and the impossibility of containing certain evils domestically drove the founding of the League of Nations. Troubled states are a global liability. They spread refugees and draw others into conflicts. Financial crises are internationally transmitted. Drug-trafficking, illegal migration, arms trade, trafficking, money-laundering and terrorism must be fought globally because the networks behind them operate globally. Disease control is a global problem as much as environmental sustainability. Conversely, development delivers gains from trade, from cooperation in science, culture, business, or tourism.

Another source is interconnectedness.Something may come with global responsibilities if the global order as such is causally responsible for certain problems in country A for which an assignment of rights would be the solution, as well as the sense in which this imposes obligations on people elsewhere. Enlightened self-interest and interconnectedness often apply jointly. To illustrate, consider an argument for a human right against any form of slavery, no matter how benign. To begin with, considerations about membership in states show individuals have claims against their state for protection also against benign slavery. The increasing intensity of transnational interactions creates opportunities for trafficking. Since in any given country individuals have a right to protection against enslavement, it is in each country’s enlightened self-interest to combat trafficking. Otherwise the number of de facto slaves in their midstwill increase. The combination of enlightened self-interest and interconnectedness supports a human right not to be enslaved in any way. Finally, one way in which concerns can become global is for them to be regarded as such by an authoritative process. We can enlist proceduralsources to argue that human rights express membership “as the global order sees it.”

So this is admittedly a more complex conception of human rights than for instance the orthodox conception. But it is guided by the idea that, in an interconnected world, there is a range of ways in which something could be a genuinely global responsibility in ways that render moral-rights language applicable. And I hope that, in spite of the complexities that arise when one spells out that idea, it’s a rather intuitive thought.

(Art by Zubeida Agha)

3:AM: Trade is something that you see as having enormous significance for political philosophy even though it hasn’t been very prominent in that context. Why was political philosophy not so interested in trade and why do you think it needs to be?

MR: Traditionally, political philosophers focused on questions about the dominant political structures of the day, such as city-states in European Antiquity, empires in early China or states in modern times. Who should wield power in these structures? How should power be exercised? Hardly anybody explored how trademight give rise to moral demands. Nor had social science fully articulated how beneficial trade was for humanity.

Now we understand the importance of trade for the advancement of humankind, historically and social-scientifically. For millennia exchange of ideas and goods across large regions has let our species advance in concert, widespread enmity and competition notwithstanding. Since World War II political and economic interconnectedness has risen to new levels. And for some decades now, trade has been structured through the Word Trade Organization (WTO), whose performance has been contested by groups ranging from economic nationalists to advocates of institutional reform favorable to the global poor. All along trade has made the world – humanity has been able to advance only because we could exchange all sorts of things that enabled people to do things that would not have been possible drawing only on local resources and holdings.

Yet trade remains elusive and profoundly difficult for philosophical thought – which explains to a large extent why trade has been a neglected topic but it is also precisely why it’s such an important and fertile domain for philosophical inquiry. What, if anything, is it about trade that generates obligations, and what is the nature of these obligations? Can we identify a normative ground for trade-specific obligations while recognizing other grounds such as common humanity or shared citizenship? How should we think about that ground in ideal theory, where everybody does as he or she ought to, as well as in non-ideal theory, where not everybody does?

These are tough questions partly because trade touches on many subjects in political philosophy but must also be properly understood historically and social scientifically. They are tough questions, but also questions that we can answer. Gabriel Wollner and I offer our answers to these questions in our forthcoming book On Trade Justice: A Philosophical Plea for a New Global Deal.

3:AM: Can you sketch for us your account of trade justice and how you hope to connect it with your thinking around global justice?

MR: Trade (specifically, subjection to the global trade regime) is one ground of justice. What justice requires for trade is best developed within such a framework, with the notion of exploitation central to how we spell out trade (in)justice. There are various ways of thinking about how trade comes up for consideration from the standpoint of global justice (“images of trade”) that can be systematically assessed in terms of philosophical merits. One such image is that trade just does not come up for moral consideration at all because it’s an interaction among consenting adults. A second image is that the moral relevance of trade is merely instrumental to other or more general goals. Hardly any philosopher has written about trade with as much as insight as John Stuart Mill has, and for him trade was but one vehicle to advance overall happiness. A third image is one recently proposed by Aaron James, for whom trade-justice consists in a certain division of jointly created gains from trade. What we argue, however, is that the philosophically most plausible account of trade from the standpoint of global justice is that involvement with the international trade regime is one in several grounds of justice, and that trade injustice consists in exploitation. That is, gains from trading are distributed justly only if their distribution is not the result of exploitation. The philosophically preferred view of exploitation, in turn, takes it to be unfairness through power. The particular version of this general account that applies to trade characterizes exploitation as power-induced absence of reciprocity.

Not all types of exploitation are problematic in the same sort of way. Some types of exploitation are stepping stonestowards a just world or a price worth paying, and as such are temporarily bearable. Agents see the world from a standpoint of constrained agency rather than that of a universal planner.

To make all this concrete, the trade-specific obligations of states and other entities (especially corporations) need to be spelled out. As far as obligations in the domain of trade are concerned, states, the most powerful entities, should shoulder the lion’s share of obligations. They ought to found an international organization devoted to trade justice. The grounds-of-justice view dilutes differences between domestic and foreign policy. The WTO must be reformed to assume the obligations of a trade organization with global ambitions. Avoiding exploitation means to empower developing countries and accept a development-oriented mandate. Other than states, companies are the most important actors in trade. Their obligations concern treatment of employees, but also their relationship with outsiders, including communities where they do business, contractors and suppliers, as well as governments under whose jurisdiction they operate. These obligations fall under the requirement not to exploit.

Questions of workers’ compensation arise as a topic of trade justice. Exploitation as unfairness through power offers the most convincing perspective on the issue. Often corporations pay workers exploitative wages. Decisions about where to produce raise questions of trade justice. Relocating firms might exploit by using power to induce failures of reciprocity. There are conditions under which such exploitation is all-things-considered justified. In relocations from one developing country to another, such conditions are less likely to be met than in relocations from a developed to a developing country. A theory of trade justice as non-exploitation also helps answer questions such as: Under what circumstances can companies deny moral responsibility for wrongdoings of suppliers or sub-contractors? When may companies cooperate with authoritarian regimes? The most promising strategies of denying responsibility for wrongs committed by suppliers are unsuccessful and cooperation with authoritarian is permissible only under a very limited set of circumstances.

All of that, again, is argued in Gabriel Wollner’s and my forthcoming On Trade Justice: A Philosophical Plea for a New Global Deal. Our approach is very much historically embedded. Postwar history has seen several efforts to create a trading system that have eventually led to the WTO. None of these did justice to developing countries; they have largely been exploitative. It is time for a New Global Deal.

3:AM: One of things you are also hoping to achieve is to link your ‘grounds of justice’ view to the more ancient definition of justice so before we see how you do this can you say something about what you take that ancient definition of justice to be?

MR: Let me take a step back here. This question turns to my forthcoming book On Justice: Philosophy, History, Foundations. It might seem to be somewhat peculiar that at this stage I’d write a third book with the words “justice” and “on” in the title. I ended up writing that book because, over time, a host of questions arose about the general approach in On Global Justice. Why is this overall way of thinking about justice better than that of other people? Does it make sense to speak of justice in a global context at all, or is it merely another exercise of “us” talking about “them”? Is there even one notion of distributive justice? And if so, what kind of thing is it (a value? A norm? what else?), and how does it connect to other moral vocabulary? And similar questions arise about the notion of grounds of justice – what are they? How to prioritize among them, etc. So the situation is that, on the one hand, these questions arise once you go the way I’ve gone with On Global Justice (and that book addresses many of them already, up to a point); on the other hand, the contemporary philosophical climate offers much resistance to the plausibility of the kind of theorizing that’s needed to answer these questions.

Similarly, while it has only really been through Rawls’s work that distributive justice became as prominent to political philosophy as it is today, there’s also a flurry of very critical stances towards both the centrality of justice and the idea that it would be philosophers who inquire about it. So it’s before all this background that this book was written. And there’s also the conviction in the background that doing justice to such a complex notion as justice (pardon the pun) requires different types of inquiry. It requires analytical inquiry, to make sure what is said meets standards of rigor and precision. But it also requires historical and comparative inquiry, since the importance of “justice” is such that one can’t just make one’s own stipulations about what the term is all about and start making arguments around that term, but should pay close attention to how the term has been developed before. How we can understand the notion today must somehow reflect how others have contributed to its trajectory. That’s just a way of paying homage to the great importance that justice arguably has in the political domain.

To insist on justice, in everyday parlance around the world, often is to insist on being treated with impartiality; having existing law or practice applied without irregularity; or being reassured that laws or practices are adjusted as appropriate. Concrete experiences of injustice and justice are deeply embedded into everyday life, with its status-quo biases, cultural complexities and limited perspectives. But behind such concrete experiences, at a higher level of reflection, we find a more abstract underlying notion of justice. As far as that notion is concerned, the perennial quest for justice is about making sure each individual has an appropriate place in what our uniquely human capacities permit us to build, produce and maintain and is respected appropriately for her capacities to hold such a place in the first place. The link between this notion and concrete experiences of injustice or justice is that one’s community is the location where humanity’s accomplishments manifest themselves in life-worlds. It is in such life-worlds where these achievements either become available or are denied. Just communities give each her own in some ways. Unjust communities fail to do so, more or less egregiously.

This more abstract understanding of justice arguably has several advantages. To begin with it allows us to develop a reasonably unified understanding of what justice is all about, even to offer an account that is genuinely global in outlook. Moreover, it allows us to see justice as the most stringent moral value, in light of the tremendous importance for human flourishing (no matter how precisely we choose to understand it) of having an appropriate place in what human efforts jointly provide. And also, this account allows us to see justice as a value with substantial internal complexity that in On Global JusticeI spell out in terms of a theory of multiple grounds of justice.

(Art by Zubeida Agha)

3:AM: So how is your grounds of justice view linked to the ancient view of justice – is it in some ways a development out of the older version?

MR: So, yes, roughly speaking what I want to say is that pluralist internationalism as I develop it in On Global Justice (as well as also in the co-authored book on trade) is the most plausible contemporary understanding of an underlying notion of justice that in turn can be traced throughout the history of human affairs. What would be recognizably theorizing about distributive justice is something we can find across the ages and cultures, with many interesting cross-connections. And all that theorizing responds to particular needs and demands that arise from the kind of creatures that humans are.

Clearly to any philosopher with decent training this will sound like something somewhere between highly ambitious and rather misguided. At the very least a lot needs to be said to keep it away from the latter side of that spectrum. So the book begins with a chapter called “Apologia for Justice,” which explains the general stance the book takes – that he burden of proof is on somebody who, like me, wants to argue for the plausible centrality of distributive justice in contemporary discourse. Then there are several chapters investigating the nature of political philosophy as part of political discourse as well as the possibility of global political thought. It’s after all rather non-trivial what it would mean for there to be a global political discourse if this is supposed to mean anything other than “us talking about them.” Here again I’ve found a sociological theory quite helpful – John Meyer’s world society analysis, which has given me a neat ontology that works very well for my purposes. I have written a couple of papers with John Meyer to develop the connections and also deploy that approach in this book.

The second part of the book then argues that given our genetic make-up, it is natural that a concern for a place in what we jointly produce and maintain would become of primary importance in our moral lives. I explore how this question was understood very differently across locations, cultural contexts and periods while recognizably being the same question, as a rule in a manner that contrastedjustice with global concerns. Over centuries, the scope of people included in considerations of justice increased, as did their subject matter. The classics of justice from Plato to the present can be embedded into such a narrative. In the 18thcentury, our contemporary notion of social justice emerged, and in the 20thcentury that of global justice. And, yes, where I want to end up then is at a point where I can say that pluralist internationalism is the next plausible step in this overall quasi-historical narrative, paying homage to the fact that our justice-theorizing must always be deeply indebted to what’s come before.

To be sure,systematic arguments need to establish that pluralist internationalism is the right vision for how we should live together in this world. But at the same time, we can’t act as if any given philosopher could just determine on their own what distributive justice is all about, and with that project a historical narrative will help. And third part of the book then engages with a host of analytical questions – with the claim that justice is a value; that its demands are the most stringent moral demands; with the ontological features of grounds of justice; and I also try to establish my approach as a global-public-reason approach, resisting general criticism of public-reason approach. On Global Justice and On Justice: Philosophy, History, Foundations, together are meant to establish the plausibility of the overall grounds-of-justice approach, as well as my version of it specifically (pluralist internationalism).

3:AM: You’ve written about issues arising from immigration in Germany – you’ve discussed replacing a notion of Leitkultur with Orientierungskultur, with both of these terms replacing multiculturalism. So why is multiculturalism not helpful, and why is Orientierungskultur the preferred option? Is this a view that you think can be generalized to other states or is it specifically a German solution to a specifically German context?

MR:So here you are alluding to a recent paper of mine that seeks to popularize the notion of Orientierungskultur – a term I deliberately so far have kept in its German version. The notion of Leitkultur has been used by conservatives in the German immigration debate to capture the idea that our (German) living arrangements ought to be shaped by a shared cultural identity. Leitkultur contrasts with a multiculturalism that sees multiple cultures side-by-side on equal terms. German philosophy, especially Kant, has bestowed an intellectual meaning upon an originally geographical notion (orientation) that is ubiquitous in everyday German, making “Orientierungskultur” a natural construct in German. English lacks such a background in the usage of “orientation,” which makes talk of orienting culture odd. That notion allows us to say there is an inevitably amorphous but recognizable German culture whose prominence in public life provides a grounding for many and prevents them from feeling alienated from the society they helped build; at the same time, for some domains of public life not participating in default behavior is not merely tolerated but acknowledged as a genuine alternative. Crucially, one way of orienting oneself is to turn away.

The shadow of fascism makes debates about German identity rather torturous: as those who have talked about Leitkultur have experienced, somebody inevitably tries to gain political capital drawing Hitler-analogies or evoking the risk that others might. Self-declared opponents then often repackage similar claims without using the term. Of course, some opponents do reject the ideas behind Leitkultur and do not repackage the ideas using a different term. Jürgen Habermas, for one, thinks a multicultural constitutional patriotism is all we need. But the questions supposedly answered through Leitkultur plainly arise: an increasingly diverse and globally economically and politically integrated country nonetheless must respect the desire of large parts of its population to inhabit a cultural space that does not deviate too much or too abruptly from what they are used to. Nobody has a right to expect that things do not ever change. But too much change, or change coming too fast, overwhelms people. They can rightly complain that their community does not take them seriously as members. So the notion of Orientierungskultur is meant to preserve valid points made on the various sides here.

For some, Orientierungskultur is what they mean by Leitkultur. But Leitkultur has connotations with undue dominance. Also, what is attractive and important about one tradition having public prominence is better theorized under “orientation.” For others, Orientierungskultur might be related to what they mean by multicultural constitutional patriotism.But theorizing about the background culture does a better job articulating the historical contingencies of our political relationships than multicultural constitutional patriotism. However, Orientierungskultur also shares important features with constitutional patriotism and Leitkultur. It shares with the latter the idea that one culture has a default status, and with the former the insistence on increased respect for adherents of non-mainstream cultures.

Thinking about German Orientierungskultur, and thus about German culture as something that orients people in Germany, allows for a credible articulation of a liberal ideal for Germany while also addressing worries about alienation as they arise in a globalizing world. As somebody who is both a German and American citizen I have thought about whether this notion could find any traction in the US context. So far my inclination is to think that it couldn’t. But articulating why it would make sense then in the German but not in the US context would require more thinking than I’ve so far been able to devote to this project. And given how sensitive all thinking connected to identity is these days (in the US even more than in Germany) I’d be reluctant to say anything about it before I have something that I can really substantiate.

3:AM: Talking about Germans, you’ve also done a fair amount of work on Nietzsche. Can you talk a bit about your interests in Nietzsche and possible future plans to work on Nietzsche?

MR: Yes, so I’ve always had a side-interest in German 19th Century philosophy. Basically, in the 19th century the Industrial Revolution was transforming societies, science made enormous strides and the political changes both domestically (in European countries, that is, so the liberal movement, then the socialist movement and the various conservative reactions to those) and internationally (the completion of the colonial project in large-scale imperialism) set the stage for our current realities (for better and worse). This was just a breathtaking background canvas for philosophy, and gave rise to an incredible range of thought, including Nietzsche’s

Nietzsche clearly is one of history’s most colorful philosophers. He actually trained as a classicist, at a time when the love of all things Greek was wide-spread in Germany, a cultural phenomenon in fact that is hard to relate to these days when learning ancient languages seems almost quixotic to many. But back then, in the midst of all that change, a quest for a new kind of orientation led to a renewed interest in the ancient world. In addition Nietzsche was also fascinated with the emerging natural sciences and tried to recast many of the traditional questions of philosophy in their light. And then he took a devastating (and I’d say devastatingly clear-minded) look at the impact of Christianity on the world, and especially at how many philosophers (including Kant and the utilitarians) had been confident that they had escaped from Christianity’s long shadow only to be stranded in it after all, one way or another. All of that generated a writing trajectory of amazing breadth, depth and originality whose true value (and thus value from other people’s intellectual and political projects), I think, has only come to be appreciated in recent decades.

To elaborate a bit on the point about the Christianity’s long shadow: Nietzsche believed that the Ancient Greeks (at least before Socrates came along) had a very healthy attitude towards life. In particular, when one of them did something foolish or even heinous, they would blame the gods for “bewitching” them. Christianity introduced a different type of deity, one who was associated with a universal standpoint of assessment visa-a-vis which almost all people would inevitably fall short. So to that God no blame could be shifted; on the contrary, the existence of that God would lead to all sorts of self-tormenting in the form of guilt, which precisely is that sense of falling short from the standpoint that matters first and foremost, that of being a child of God. That standpoint would also deliver ideas about equality: after all, qua children of God all humans would matter equally from that standpoint that is most relevant.

Nietzsche thinks there’s a historical story to be told about how Christianity (the priestly class) could not only develop its theory in ways that persuaded even highly educated people (basically, by adopting much from Plato) – but could also take over the Roman empire, from there the Germanic world, and from there indeed much of the world as a whole. Centuries later, of course many of our basic moral intuitions stem from generations of socialization in a Christian world (and even in countries that are not explicitly Christian that Christian influence has been strong, through the spread of all sorts of Western ideas during colonialism). These moral intuitions still inform contemporary philosophy, but Nietzsche thinks a full understanding of what is actually involved in the notorious “death of God” would require a substantial reconsideration of all sorts of things, including belief in equality or anything like universal human rights.

My own work on Nietzsche started in earnest when I was Alexander Nehamas’s teaching assistant at Princeton. He tended to emphasize different aspects of Nietzsche’s work than what stood out to me, ideas around the ability of individuals to become the authors’ of their own lives. For me Nietzsche’s efforts to draw the emerging sciences into philosophical thinking captured more what made Nietzsche important. At the same time, I will be forever in Alexander’s debt for having encouraged me to develop my lines of disagreements with him systematically. In the process, I started to be rather intrigued by the second and third treatise of the Genealogy, which are much tougher reads than the first and thus get much less attention both in teaching and in scholarship. The common view on the second one had been that there wasn’t really a coherent interpretation of it. But after reading it again and again I thought that such an interpretation could be offered, and I did so in a 2001 article entitled "The Second Treatise in On the Genealogy of Morality: Nietzsche on the Origin of the Bad Conscience", which appeared in the The European Journal of Philosophy. The crucial move there was to see that, in that treatise, Nietzsche uses the term “bad conscience” in different senses. One of them simply denotes an early form of the mental that would then interact (in ways that treatise seeks to explore) with debtor/creditor relationships as well as with the activities of the priestly class – so that in the end the mind would be taken over and dominated by bad conscience in the contemporary sense. After that also wrote on the third treatise and on several other themes in Nietzsche’s middle and late work, including his (on the fact of it perhaps odd) admiration for justice and his own positive ideals of human excellence. My thinking about Nietzsche has been much influenced by Maudemarie Clark, Brian Leiter, John Richardson and Bernard Reginster.

In the back of my mind I have the idea of eventually writing a book called Nietzsche for Political Philosophers: Genealogy, Equality and Humanity. I’m not sure when this can become a reality (if it ever will be), and the path to a book like that would also involve a lot more thinking about the themes on which I have already published. But the basic idea is this. Nietzsche is generally a fighter against prejudice wherever he sees it. Many philosophers would think that is precisely the route towards egalitarian commitments. But Nietzsche takes a decidedly hierarchical, aristocratic approach to social organization. Therefore he becomes the nemesis of those of us who see ourselves working on a kind of egalitarian plateau (including myself!). He thinks that only the bad kind of intellectual self-deception can lead to the endorsement of any kind of egalitarian ideals – and generally, once we do away with the many ways in which our intellectual legacy deceives us, we will be led to a fair amount of philosophical debunking of a lot of moral notions we hold dear. (Ruediger Bittner recently carried out such a project of debunking in Nietzschean spirit, called Buerger Sein, Being a Citizen. As far as I know, there’s no English translation yet.) My own philosophical commitments (and what I think are arguments) are very much contrary to this – but Nietzsche is the interlocutor whom one needs to engage with in this context. (Carl Schmitt is another, but that is a story for another time.) Over the last several years I’ve been teaching a freshmen seminar at Harvard about Nietzsche, and that’s one of my favorite teaching activities in any given year.

3:AM: And finally, are there five books you could recommend to the readers here at 3:AM that would help take us further into your philosophical world?

MR: Yes…

So I’d mention here

Aaron James, Fairness in Practice: A Social Contract for a Global Economy

This is the first book-length philosophical treatment of trade, which set the stage for a further development of my own views on trade that are now forthcoming in my book co-authored with Gabriel Wollner

Leif Wenar, Blood Oil: Tyrants, Violence and the Rules that Run the World

This book illustrates admirably how philosophical thinking and attention to the social sciences can generate far-reaching advice for public policy.

Georg Krücken and Gili S. Drori, World Society: The Writings of John W. Meyer.

This is a collection of work by one of the pioneers in sociology of world society theory, from which I have learned a lot about how change occurs in the world. This approach has provided me with a very useful ontology for my own work.

R. McNeill and William H. McNeill, The Human Web: A Bird’s Eye View of Human History

Together with Meyer’s book this work by two historians has persuaded me that in the domain of political philosophy as well a genuinely global standpoint is possible and required.

Max Tegmark, Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Fascinating discussion about how human life and societies might change through the development of sophisticated technology. This hasn’t been part of the questions here, but ethics/human rights and artificial intelligence/technology are the next big things on my radar.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End TimesSeries: the first 302