Democracy Naturalised

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I’m completely in agreement with you in being revolted by right-wing nativism of the sort pushed by Trump, Johnson and Bolsonaro. I’ve always been a typical denizen of the U.S. center-left. After all, I grew up in the anti-war McGovern days (fearing the draft and wishing I’d gone to Woodstock), and I only later came to throw in some Henry George. The thing is, it doesn’t matter where we are on the left-right continuum.'

'Distilled Populism ... by its lights, nobody’s take on values should be given any more weight than anybody else’s. It leaves morals to the angels and takes prudential value (that which makes individuals or groups better off) to be a function of what individuals and groups want .'

'“CHOICE voluntarism” is a theory of prudential value that takes its inspiration from a few remarks by the American philosopher Everett Hall from the mid-1940s.

The “voluntarism” here means that what prudential values there are in the world are created by valuations. No approval or disgust, no value. However, values should be understood to be objective ;in the sense of not being entirely aboutthe valuer. So “This is good” is unlike “I’m thirsty” in not being a subjective judgment, something only about the person saying it. But either way, the values are created by valuers.The CHOICE part involves a claim that getting what one wants when one makes an uncoerced choice is a success.'

'I’m not as sanguine about direct democracy as a number of other current theorists. I think deliberation is very important, but I believe it needs to be occurring among the representatives rather than the electorate at large. I follow Anthony Trollope (of all people!) in taking the appropriate representative relation as a matter of trusteeship rather than delegation. But I also follow the American Progressives of the early 20th Century—as well as Parliamentary systems—in taking the ability to recall representatives as essential.'

'The U.S. Constitution may have been a model for government systems a hundred years ago, but now it’s more like a funky Leibnizian calculating machine that nobody sensible has any interest in except as a historical oddity. I say that it’s too much because it has silly, imaginary “rights” bandied about in it as if they were real, but that it’s also too little because the things that do require absolute protection, like freedom of political speech and association, are guaranteed only against encroachments by the U.S. government.'

'And I’m not a good prognosticator, so I don’t have a strong sense of what is likely to happen in the U.S. over the next decade. But I will admit to being disgusted, disappointed, and afraid. '

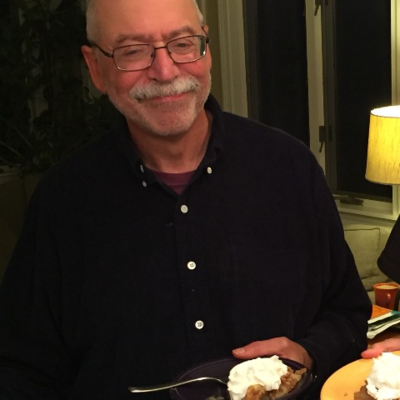

Walter Horn is a philosopher of politics and epistemology. Here he discusses democracy, distilled populism, choice voluntarism, the equal vote/equal voter paradox, ‘boundary issues’ of democracy, voting systems, the ‘separation of powers’, why the U.S. Constitution is flawed, libertarian objections to democracy, the current democratic crisis in the USA, and then epistemological issues - whether knowledge is closed under entailment, the importance of Everett Hall, and a defence of esoteric art.

On the day when US politics continues to be engulfed by the long slow coup of outgoing populist and bullshitter President Trump as Biden is inaugurated as his successor, this interview takes philosophical stock of this sombre moment.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Walter Horn: There are short and long answers to that question, and (since the short one is short) I’ll give you both. I was somewhat precocious in music and not terribly interested in anything else, so I went to Ithaca College to study music composition with Karel Husa. But it became clear to me fairly quickly that while music majors were hunkering down in practice rooms at all hours dealing with all their one-credit courses, those who were majoring in humanities subjects were getting high and playing frisbee on the main quad. So, I quickly found something else to get a degree in.

But the longer answer gives a clue as to why it was philosophy rather than, say, French lit. Of course, we’re drawn to fields in which we do well and receive positive reinforcement, and the philosophy faculty at IC, particularly Stephen P. Schwartz, was encouraging. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. I attribute a good chunk of my early affinity to various philosophers and philosophies to my anxieties, principally about dying. My family was not religious, and I was a fearful sort, which may be why I was drawn especially to philosophers who promised some kind of “continuance” without reliance on any personal God. I don’t know how many other young philosophiles have taken similar routes, but I started out reading everything I could understand by the English idealists, especially Bradley and Bosanquet, and threw in a smattering of German post-Hegelians. I liked the idea of being absorbed into some kind of impersonal Absolute when the time was right.

When I was an undergraduate—and this was still true later, when I taught there for a couple of years—Ithaca, New York was a hotbed of Wittgensteinianism, partly because Wittgenstein had visited Cornell and lived with Norman Malcolm for a while. So, it didn’t take long for me to see that my youthful favorites were, let’s say, uncool choices. By the time I got to grad school at Brown, I had switched my allegiance to Spinoza, who, while saying a lot of the same sorts of comforting things, was more acceptable, in part because he lived in the 17th Century, but also, I think, because his “proofs” regarding God and human immortality were so obscure and pseudo-geometrical. That made him a more acceptable cognoscente.

Anyhow, I received at Brown the typical rigorous training in analytic philosophy that one got from a faculty then featuring Roderick Chisholm, Ernest Sosa, and Philip Quinn, and, although I wrote my dissertation on Spinozistic metaphysics (under James Van Cleve), by the time I left Providence I had come to believe that nearly every single argument in the Ethics was invalid. In spite of that recognition, I think it’s possible to see from my first published philosophy paper, “A New Proof for the Physical World,” that I hadn’t quite given up on rationalism. I still wanted the world to somehow be knowably less terrifying—at least to the sagacious few. And this longing for dependable solidity and everlastingness revisited for many years, at some point taking me into a Huxleyan foray into meditation, Vedantism, and mysticism. Those inclinations can be seen as late as 2003, in my book, Perennial Solution Center. I was still needy—although I’d become a little less so. I didn’t claim you could prove anything from mystical experiences in that book, but I did suggest there is some sort of psychological law that makes one who regularly reaches sadhana start to believe in comforting things. I think there is a neediness evident in any hope for a perfectly dependable, peace-producing mechanism.

This may seem pathetic, but it’s remarkable how many philosophers apparently spend their entire careers attempting elaborate proofs for the comforting things their parents drummed into them when they were children. Plantinga and Van Inwagen are two prominent thinkers who immediately come to mind here, but there are countless others, including those who are not Calvinists. And it should not be thought that those whose parents didn’t feed them nice stories about how the world works can’t suffer from similar foibles. At any rate, it seems to me that a substantial amount of ostensibly grown-up philosophy is based largely on fear and trembling. I think Dan Dennett may have said something about this tendency somewhere. Anyhow, I can’t deny that that species of anxiety dug a significant section of my own path. I hope I’ve finally gotten most of the way off it!

3:16: Let’s start with your new book on democracy. It’s about populism, and for me and many people that’s the politics of Trump, Johnson, Bolsonaro and others on the right. It’s a very unappealing brand to me. But you want to take another look and in a way distance populism from these guys and make it more the sort of thing Frank Capra made films about and Randy Newman sang songs about. So can you sketch for us what your ‘distilled populism’ involves, what elements of stereotypical populism it distances itself from (if any) and how it helps us understand what you mean by democracy?

WH: Oh, I’m completely in agreement with you in being revolted by right-wing nativism of the sort pushed by Trump, Johnson and Bolsonaro. I’ve always been a typical denizen of the U.S. center-left. After all, I grew up in the anti-war McGovern days (fearing the draft and wishing I’d gone to Woodstock), and I only later came to throw in some Henry George. The thing is, it doesn’t matter where we are on the left-right continuum. Most people, whatever their politics, don’t give two straws about democracy. Nearly everyone just believes that their country should do what they want, not what the majority may want. Authentic democracy has a low priority, not just for Trump and his followers, but for nearly everyone. V.I. Lenin was as definitive about the supposed inanity of what he called “bourgeoise parliamentarism” as any gun-toting acolyte of the National Rifle Association. One group simply knows that proletariat exploitation must be ended at all costs, while the other knows that no one may be prevented from carrying weaponry around without a blatant violation of some God-given right. So, neither cares a bit about what the majority may want: if the multitudes don’t agree, they’re simply wrong. You see the same thing on the pro-choice/pro-life issue. It is only those who believe the majority is with them at the moment who have any interest in putting the matter to a vote.

These anti-democratic attitudes stem from two things, I think. First, there is usually a Platonist or “non-natural” picture of values. On that view, values are thought to be out there in the heavens somewhere, just waiting to be plucked. Second, there is a very immodest view about what it takes to grasp one of these eternal verities. The existence of a strongly held belief about guns or prenates or ownership of the means of production is usually taken as sufficient evidence of correctness. And that means that anybody who disagrees is wrong. It doesn’t matter if 80% of one’s community or country or even the entire population of the earth has a different view of the matter.

Distilled Populism is a much more modest position. By its lights, nobody’s take on values should be given any more weight than anybody else’s. It leaves morals to the angels and takes prudential value (that which makes individuals or groups better off) to be a function of what individuals and groups want . It doesn’t disparage scientific expertise in the matter of facts. But it insists on disengaging facts from values and denies that science can be the arbiter of the latter.

Now, I want to stress that there are limits even to what I believe may be democratically authorized. In addition to the off-limits empirical matters, we cannot have slavery or mandatory ethnic ghettos, or limitations on political speech. But unlike other political theories, distilled populism takes all such constraints to follow from the nature of democracy itself rather than from any “natural rights” we’ve been “endowed” with. It simply says that if there is racial, gender or other discrimination, democracy cannot function correctly. We would then not be able to determine what the people want in an accurate, unbiased way, with each person treated equally and each vote given the same weight.

No doubt, distilled populism can be scary when it asks us to let go of abstract notions of “justice.” To give an example from pop culture, consider the plan of Thanos in the recent batch of Avengers movies to kill off half of all the persons in the universe because of his environmental concerns regarding over-population. Obviously, if Thanos makes and carries out this decision on his own, he’s an unalloyed despot, regardless of any niceties of his goal. But suppose there is a fair vote on the subject, and a majority of sentient occupants of the universe decides that the elimination tomorrow of half the universe’s population (picked randomly) is preferable to everybody likely dying within ten years if no such drastic action is taken. Many would say that not even a super-majority should be allowed to make decisions of that kind. They would likely be moved by the thought that human beings—and other sorts of persons too—must have a right to life that may not be abrogated even for altruistic reasons. But genuine populists will not have that reaction. They will certainly check carefully to see if the election was really fair in every important way (and maybe will hide under their beds after hearing the result), but they will not insist that it is despotism to carry out even this terrifying manifestation of the will of the people.

3:16: What is ‘choice voluntarism,’ how does this naturalize democracy and why do you think intrinsic prudential goods necessarily involve likely net increases in successful free choosing?

WH: What I call “CHOICE voluntarism” is a theory of prudential value that takes its inspiration from a few remarks by the American philosopher Everett Hall from the mid-1940s.

The “voluntarism” here means that what prudential values there are in the world are created by valuations. No approval or disgust, no value. However, values should be understood to be objective in the sense of not being entirely about the valuer. So “This is good” is unlike “I’m thirsty” in not being a subjective judgment, something only about the person saying it. But either way, the values are created by valuers.

The CHOICE part involves a claim that getting what one wants when one makes an uncoerced choice is an ( ex ante ) success. I don’t deny that getting what one wants may be bad for one in the long run, but I think we must start with the axiom that, all else equal, it’s a prudential good to get what one wants. I therefore take it as axiomatic that only such ex ante successes can be intrinsically good. I suppose one might reasonably object that this is tantamount to accepting that our access to free autonomous choosings (aka “the pursuit of happiness”) should be taken to be a natural right that we have. My only response to this complaint is that, whatever we decide to call the undeniable niceness of successes, even philosophers have to start somewhere. But although CHOICE involves the axiom that only ex ante successes can be intrinsic goods, it does not rank one autonomous gaining of something above or below another one. It does not presume to tell us that poetry beats pushpin. On the other hand, as we know that each success has something required of intrinsic prudential goods, we can say that two of them is better than one. That’s one of the clever things about Hall’s approach here. He realized that even if we can’t make measurable comparisons based on qualitative items like intensity of desires or pains, we can still compare individual successes due to their fecundity - how likely they are (based on what we know about psychology, economics, environmental laws, etc.) to result in future successful choices. Since we have taken what we might call “ The more good, the better”as axiomatic, if, using our knowledge of science, we can infer from some goal that additional goods will result from its being obtained, we can say what choices are best for people and groups.

It may be wondered why I’m sanguine about prudential values at the same time that I’m so skeptical about moral claims. The reason is that I find promise in CHOICE as a background theory for prudential values. In my view, this allows me to argue that prudential value claims are analogous to claims about the physical world or other minds. We not only believe such things as that it’s snowing outside, and may have perceptual evidence for them as well, but we also have a coherent background theory (including physics, biology, and the other natural sciences) that we can use to make sense of what is going on if the claim is true. If such theories are plausible and coherent, I think that if one of our justified beliefs about that realm happens to be true, we may know it. I don’t deny that various moral propositions are also widely believed, and I think we have evidence for many of them as well, provided by various emotions like sympathy or revulsion. But in the area of ethics, I doubt we can have knowledge even when our warranted claims happen to be true. That’s because I don’t think there’s any coherent background theory available to make the entire ethical world comprehensible. Without that, moral beliefs seem more analogous to astrological predictions or claims about magical powers. After all, those too may be believed, and some may have (inductive) evidential support from past predictions that happened to come true, but the entire picture is just nonsensical. Where there is that lacuna, I don’t think real knowledge is possible even where there happens to be a confluence of belief, justification, and truth surrounding some assertion.

It’s true that hedonists have made attempts at a background theory for ethics since Bentham’s time, but I don’t think any of those attempts have fared very well in the face of a century of criticisms. Of course, CHOICE may do no better if doubters ever care enough about it to get around to throwing a thousand knives at it too, but, at present, it seems to me entirely alone in being both a game and in town.

3:16: How does your approach to choice mean that both votes and voters can be considered equal without contradiction?

WH: The equal vote/equal voter paradox hasn’t gotten as much ink among writers on democratic theory as it probably should have, although I do remember Dahl spending some time on it. On the other hand, it’s closely related to questions about equal opportunity versus equal outcomes which have certainly gotten plenty of attention in the world of welfare economics. The problem is that if each voter should be treated with equal respect, it seems we should treat their votes differentially, since some things are very important to some people that are quite minor concerns to others. Equal weighting suggests unequal treatment when, for example, one voter really needs something—like medical care—while another may have only a slight interest in her taxes not going up a few bucks a year. Failure to weight the votes on such matters seems to be disrespecting the passionate feelings of some voters when there is near indifference among those with opposing views.

CHOICE handles this by ignoring intensities entirely. Since we can’t really compare my headache pain with your stomach-ache or the intensity of one person’s desire for a kidney with another person’s desire not to pay more taxes, CHOICE makes all votes, like all choices, completely equal. As Hall put it, we make choosers equal precisely because each is the creator of equally-weighted values whenever they make a choice. But this, too, must be taken as an axiom; it’s not the sort of thing that is subject to proof. And again, such a determination is bound to be controversial, since most people will insist that what is a “correct decision” on these sorts of questions comports with their own views about how terminal kidney disease should be compared with purchasing a third yacht. A genuine democrat will resist coming to such conclusions. It is important to remember, however, that CHOICE does not require us to ignore the fact that Jones getting the kidney may allow for more future successful choices to be made in the world than Smith’s getting another fancy boat will.

The other important thing about CHOICE is that it has two distinct aspects and refuses to ignore its personal-success aspect when there is empirical information relevant to its reasonable-expectation-of-fecundity aspect. The personal desires of both the current choosers and any potential future choosers are never allowed to become irrelevant because of expert judgments. That means choices—including votes—cannot appropriately be taken to be epistemic, truth-tracking items. As a result, nobody’s vote can be worth more because the person who casts it is smarter or better educated, or worth less because a particular desire is stupid or based on incorrect empirical information. The theory is unequivocally opposed to elitist paternalism of that sort by distinguishing values from facts. It may be that my choice or vote is “poor” to the extent that it will not actually increase my—or my group’s—net future successes, but CHOICE does not allow for its second conjunct (the one involving the likelihood of an increase in net successes based on the best science) to replace or overwhelm its first aspect (which involves autonomous choosings). Each is essential. In addition, claims about the net numbers of (probability weighted) future successes can only be made with extreme diffidence, even by experts. So epistocratic and guardianship theories are non-starters.

3:16: You discuss ‘boundary issues’ of democracy – questions such as deciding who gets to be enfranchised, whether interests or geography is most relevant for issuances of group voting rights – don’t you? How do you approach these issues and what do you think the answers are?

WH: Those issues are indeed some of the main staples of writings on democratic theory. They have seemed almost intractable, so I think it’s exciting that they fall into place relatively easily once democracy is put on the pedestal where I think it belongs. For example, since the right to vote is taken to be inalienable and not secondary to any supposed Platonic principles regarding “The Good,” it can never be acceptable to deny voting rights based on, say, an allegedly evil nature, or the prior commission of a felony. Again, if we see that votes are analogous to autonomous choices, we can consult the literature on psychological development and find out roughly when the cognitive skills for such activities arise. If we do this, we’ll find that sufficient maturity is usually reached in the mid-teens, around the age of sixteen. It doesn’t matter whether someone pays taxes or owns property, or is reliably honest, or knows very much about what political representatives are supposed to do.

Turning to whom governmental edicts apply to, that polities must be geographic entities, rather than some kind of function of relevant interests is simply a fact about power and the world. So, anybody who lives for a while in a particular area should be allowed to vote there, and the laws passed by that group will apply to her. It’s that which makes one a member of some jurisdiction, a part of “the people.”

It will be asked if a polity can be allowed to build walls in an attempt to keep out everybody or even some particular group. Or if a group can (even democratically) prevent the exit of those who want to leave. Here again, the answers provided by distilled populism will likely be met with howls of protest, because such decisions do seem clearly available to the people. As I say in the book, if a group of people is cruel or xenophobic, there seems to me to be no reason to expect the polity they make up to be anything other than cruel or xenophobic. It’s their (to my mind, reprehensible) country to try to make homogeneous if they want. However, if any of these “unwanted elements” nevertheless get inside this hellhole and reside there for a time (perhaps a year), they may not be treated differentially and must be given equal say in all these border and exit questions. But there is no question that support for the elevation of democracy to its proper place forces us to repeatedly remember that it is not a theory of justice or goodness. Democracy is about appropriate governance only. If we want to allow only a special, tender sort of government, the constraints we wish to enforce mean that we aren’t really democrats after all. But it may give some comfort to also remember that real populism never allows for any restriction of equal protection/treatment among all residents of any polity.

3:16: Your book focuses very much on voting systems – which is the subject of a great deal of action in the USA at the moment given Trump’s bogus legal challenges to the last Presidential election. So, what do you advocate as an appropriate voting mechanism and how will ‘approval voting’ and ‘the single non-transferable vote’ bring about majoritarianism?

WH: Yes, my position is plebiscitary, entirely proceduralist even. There are many anti-democrats whose revulsion of the atrocities they’ve learned to have been perpetrated by Bolsheviks or sans-culottes or brown-shirted Nazis cause them to miss the fact that none of those groups actually subscribed to democracy at all. Authentic democracy requires an accurate determination of what the people really want. And this is done not by measuring the decibel levels at rallies or the number of weapons in people’s basements, but by correctly and fairly assessing what equally-treated individuals in a polity want and figuring out how to aggregate those choices correctly. The Bolshevists, for example, shut down the nationwide Constituent Assembly of 1917 in very short order, and, to give another example that sometimes comes up on these matters, in Burundi, it wasn’t any edict of the fairly elected Ndadye in 1992 that resulted in the subsequent genocidal activities of both Tutsis and Hutus, it was rather the reaction to that election by those who didn’t care for the result.

As I’ve said, according to CHOICE, getting this or that person elected or policy enacted should be deemed to be what a particular voter takes to be a representative or policy that would make his or her life the slightest bit better. Approval Voting (AV), wherein each voter checks off all the options that would count for her as minimally approvable, mirrors this conception perfectly. It has many nice consensus-finding qualities that are detailed in the Brams and Fishburn book on that topic. (Readers can find out quite a lot about this scheme by checking out the website for the Center for Election Science.) In addition to its CHOICE-mirroring qualities, AV avoids Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem by eschewing preferential rankings, because, again, it ignores “intensities.” And AV eliminates advantages to the status quo that can be created by the shenanigans of those who set the agendas of legislatures or committees.

But while AV gives a general sense of what the people want, its very consensus-building features prevent it from painting a very fine-grained picture of the general will, so, as Mill and Dummett have pointed out, it makes sense for representative bodies also to have members who are responsible only to particular minorities, rather than having everyone in power responsible in only a somewhat fuzzy way to everybody. The Single Non-Transferable Vote (SNTV) provides a focused, proportional representation that indicates what is most important to various groups, and it does so in a unique way because it again side-steps Arrow by allowing only one favorite representative (and thus, minority group) to be picked by each voter. This system has been used a bit around the world, and not to particularly good effect, but I argue that it has never been implemented correctly. To do that, the amount of authority of each representative picked via SNTV must be a function of the number of votes received rather than (as it has always been used) a function of the proportion of seats it causes to be filled.

I suggest a tentative way in which the two very different voting schemes I advocate might be combined to give a proper picture of “what the people want.” I take it to be a majoritarian package, but I suppose some would disagree; this will depend on one’s definition of “majoritarian.”

3:16: It’s very much a theory that tries to make sense of the USA. So what level of directness are you recommending, and what’s your view about representatives – are they delegates or trustees on your theory?

WH: I’m not as sanguine about direct democracy as a number of other current theorists. I think deliberation is very important, but I believe it needs to be occurring among the representatives rather than the electorate at large. I follow Anthony Trollope (of all people!) in taking the appropriate representative relation as a matter of trusteeship rather than delegation. But I also follow the American Progressives of the early 20th Century—as well as Parliamentary systems—in taking the ability to recall representatives as essential. I think direct democracy is fine if it is limited to the area of recalls, referendums and reversals of certain types of judicial decisions, but I hasten to note that the vote on Brexit was only incorrectly called a referendum. By asking “Stay or Leave?” it was actually a poorly worded initiative petition. A proper referendum requires the representatives to first pass something but then provide the people the opportunity to undo it. It’s important to get these things right if one is to have a correctly functioning democracy. Recall, not impeachment. Referendum, not initiative. On crucial matters, re-votes, not supermajorities. Etc.

3:16: You think that the ‘separation of powers’ has gone too far don’t you? Why and what’s your solution?

WH: Yes, I think your Parliamentary system does a better job in this area than U.S., which relies on a multitude of cuckoo Goldberg Machines. We have all these dearly held Madisonian maxims about who is allowed to do what that, while partially ignored, nevertheless make things pointlessly inefficient and litigious. It’s a system that the U.S. “Founders” largely based on their fear of losing their property to the riff-raff.

3:16: You generally think the U.S. Constitution is flawed, don’t you? Why do you say it’s too much and too little – and why doesn’t this (among other things you raise in your theory) send out alarm bells that the theory even if it holds together rationally is pragmatically a dead duck – the voters in the USA are hopelessly split down the middle and there’s no way you could get enough agreement to change the Constitution – not without a civil war or something is there? I guess this is a question about whether your philosophizing about democracy can only be a theoretical exercise or whether you believe philosophy like this can make a difference?

WH: Yes, I think our Constitution is a big mess. There was a nice forum on this matter by a number of experts in the field that appeared in Harpers a couple of years ago.

The U.S. Constitution may have been a model for government systems a hundred years ago, but now it’s more like a funky Leibnizian calculating machine that nobody sensible has any interest in except as a historical oddity. I say that it’s too much because it has silly, imaginary “rights” bandied about in it as if they were real, but that it’s also too little because the things that do require absolute protection, like freedom of political speech and association, are guaranteed only against encroachments by the U.S. government. Corporations, for example, are not required by anything in our Constitution to allow free political speech or association. I think the document may even be consistent with companies forbidding their employees from voting. And, as can be seen from the circus going on here over the past year, it doesn’t have nearly enough in it about how elections must be conducted.

But, as you suggest, whether or not the Constitution is a reasonable document, it’s almost impossible to amend, and this is not only because so many treat it here as if it were handed to George Washington on golden tablets by Jesus Christ Himself somewhere on the banks of the Delaware River. Indeed, one of the most important changes needed, the abolishment of the Senate, would seem to require a unanimous vote of all the states. Certainly, that is not going to happen before both the freezing and subsequent thawing of hell. So, I suppose that a book of the type I’ve written can have only the most limited effects here. Maybe elsewhere with some burgeoning democratic movement? Quien sabe? I am happy to concede that, even if all my proposals were politically feasible, I’m not sure how they could be made consistent with both our Federal structure and the webs of self-serving rules governing the operations of political parties in the various states. I leave most of those probably pointless details to others. There are more than enough in my book already.

3:16: You’ve argued against several objections to democracy, especially those brought by libertarians. Can you sketch what you think are the best arguments they have against democracy, and why they fail?

WH: A very popular contemporary criticism of democracy, made by libertarians and others, is that many voters are too stupid or too lazy (or both) to be allowed to ruin the lives of “the rest of us.” Much of the book is directed against that sort of elitism. Votes aren’t epistemic items; votes and voters must be treated equally; and so on.

Anarchists claim that governmental edicts have no “authority” or “legitimacy” over anybody who doesn’t agree with them. Distilled democracy takes a skeptical view of the very existence of such “obligations.” The Rousseauvian picture I find generally congenial instead sees individual wants that, when correctly bound up into general wills and honestly acted upon, invite our obedience. This is because we will see the actions to be what our group really does want. On such a view, there is no political legitimacy that is not just democratic legitimacy. This means that elections must be correctly designed and fairly conducted, those in power must faithfully attempt to carry out precisely what is demanded or be subject to removal, everybody must have a fair shot at being elected herself, rich people can’t buy power, and so on. But that’s it. There’s no other sort of “legitimacy” to be sought in the Platonic ether. If I don’t like what my polity is up to, I may try to change its direction or attempt to emigrate. But if democracy is being conducted as it must be conducted, its right is indeed closely tied up with its might. It is not a theory of Pareto optimality any more than it is a theory of goodness. We cannot judge its legitimacy from what we think of its outcomes. There is only the correctness of its procedures to assess.

3:16: How do you assess the current democratic crisis that seems to be engulfing the USA – and do you think if your proposals were in play the problems wouldn’t have occurred? Or is the USA inevitably lurching towards secession or some form of authoritarianism?

WH: I do think that if, say, twenty or thirty years ago, gerrymandering had been made impossible; minorities had had representation other than through geographic-only means; elections had been conducted via Approval Voting and SNTV; the Electoral College and the Senate had been abolished; Federal officials were subject to recall; campaign finance laws had been reformed as suggested in the book, and so on, we would not be in the terrifying, polarized condition we are in today. But, as already indicated, I’m not so deep into my pipe dream as to think that many of the changes I propose can ever be made here. And I’m not a good prognosticator, so I don’t have a strong sense of what is likely to happen in the U.S. over the next decade. But I will admit to being disgusted, disappointed, and afraid.

3:16: Outside of democratic theorizing you’re also interested in epistemological issues and have addressed the well-known issue of whether knowledge is closed under entailment. So can you briefly say what the issue is and how you handle it. And what’s your conclusion?

WH: It seems obvious that if you know some proposition P and know that some other proposition Q follows from P, you must also know that Q. That’s called the epistemic closure of known entailments, and you wouldn’t think it could cause any problems for anybody. But consider: I seem to know both that I’m currently sitting in a chair, and that if I’m sitting in a chair, I must not be lying in bed dreaming that I’m sitting in a chair (or floating around in a giant jar being fed sitting-in-chair feelings through a tube). But how is it possible for me, a common schlub, to know that I’m not really dreaming or being deceived by a deceitful proprietor of large, horrifying jars? That seems like the sort of claim only a Descartes-level genius ought to be able to make—if anybody at all can.

So, the problem is that there seem to be some really easy things to know that have very obvious logical consequences that everybody also knows, but the entailments are “heavyweight” items that maybe nobody can know. So, philosophers fight about whether knowledge really is closed to known entailment.

I argue in my paper that knowledge is not closed in that way by hypothesizing that something called “Categorialism” (according to which a lot of background knowledge is involved in every belief involving physical objects) is true. I then demonstrate that, given that hypothesis, if there were closure, human beings would have to know some other thing that it’s very implausible to say we actually know. So, it must be that the closure principle is false. The argument is a bit tricky and I won’t try to summarize it further here, but I think it’s interesting that it bears some resemblance to the argument I gave in my early proof of the physical world. The main difference is that in that long-ago paper, I was sketching a perfectly reliable route between what seems to us to be the case and the real world out there, while in the more recent work, I was showing that we just have to settle for the lightweight “facts” and give up necessary connections of that type. The deep stuff may just be forever out of our reach. While I never claimed that my proof of the physical world was sound—only that the conclusion followed if one accepted a controversial premise—I do think the project reflects a need for rationality that I hope I’ve outgrown. (I do still think it’s a cool, surprising proof, though.)

As I now see things, we’re just thrown wherever we may be, and it’s a place where we can imagine not only that there’s no heaven, but also that there’s neither a world of Platonic Forms nor even a real cave. We may even, as Bostrom suggests, be Sims. But we can at least tell what we want. And, with a couple of plausible axioms added we can construct what our communities want.

3:16: You’ve put together a book about Everett W Hall who you say is the first philosopher writing in English to promote representationism. So can you say something by way of introducing this rather obscure figure to us – and what were his important claims?

WH: I’ve been championing Hall since graduate school when I first read his Our Knowledge of Fact and Value. And his works have inspired nearly everything I’ve written in philosophy over the 40-years since. That book, along with his quite Tractarian/Tarskian What is Value , and his discussion of conceptual schemes and their effects on metaphilosophy, Philosophical Systems, are so jammed with brilliant, ahead-of-their time arguments, involving everything from the mind-body problem to philosophy of language and epistemology, that any contemporary philosopher who doesn’t read them is in danger of repeating (probably in a less elegant form) something Hall wrote two generations ago.

To give just one example, it’s little-known that he proposed a mind-brain identity theory the same year that J.J.C. Smart did (and what Hall proposed seems to me just as anomalous an identity as the theory famously suggested by Donald Davidson years later). It may also be worth noting that Hall was likely the only important non-positivist Tractarian. But, like the positivists, he was not terribly friendly to Wittgenstein’s later writings.

Hall really has been criminally ignored since his premature death at the age of 59 in 1960. Before I hectored William Lycan, one of Hall’s successors to the Kenan Chair at the University of North Carolina, there was no mention of Hall, who was the first American anti-sense-data representationist, in Lycan’s SEP article on the representational theory of consciousness. And, shortly before he died, Hilary Putnam, who focused on so many of the same issues as Hall, told me that he’d never heard of him. If there’s one thing I’d like my forays in philosophy to accomplish, it’s to get Hall a bit more of the attention and credit he deserves. And I’m grateful to his son, the philosopher Richard Hall, for the permission he’s given me to quote from his father’s unpublished works.

3:16: As someone who likes esoteric art, I was excited to read your response to the equally thrilling Diana Raffman’s assault on atonal music (some of which I love btw) – calling it a con game and not art! So why does Raffman think it’s a scam and what do you say to what she says?

WH: Well, as I’ve mentioned, I’ve had some involvement in music myself. After I drifted away from all thoughts of a “career” as composer, I continued to play, compose and write about contemporary music. (Interested readers can find some of my own improvised and composed work on youtube and Spotify.) Anyhow, I was astonished to discover that as late as 2003 it was still possible to find—and in a legitimate philosophy journal!—the claim that anybody who says they enjoy atonal music must be lying. As a painter yourself, you surely understand that any such assertion is insulting as well as patently absurd. So, I spent probably more time than the subject deserved disemboweling Raffman’s paper, and I spent some energy working over Richard Taruskin as well. For what it’s worth, I think the picture that there is something special (not to say sacred) about the relation between tonality and beauty in music (and, presumably. that between representationalism and beauty in the visual arts) is likely one more instance of a fearful, elitist attitude. Human beings seem to have a desperate need for explanations of their takes on values. And many are prone to say that those whose responses don’t fit some picture that suits them can only be wrong about what they prize—or even, as Raffman, Taruskin, and Stanley Cavell suggest— evil. That seems to me to be not only needy, uncharitable and divisive, but to entirely misunderstand the nature of aesthetic values.

I’ve said that I think both prudential and moral values are objective, and that we may have evidence for claims involving each type, but that only propositions including the former species may be known because of the absence of a credible background theory in the area of ethics. In the case of aesthetics, not only is there no coherent theory of beauty around, it doesn’t seem to me quite so clear that objective judgments are being made at all. That makes the role of the art critic particularly difficult, I think, because there may nevertheless be greater or lower likelihoods of pleasurable responses connected with one item as compared with another. So, there is, again, a type of evidence available in the case of artworks (and naturally occurring events like sunsets as well). But it’s not so clear—at least to me—what this evidence is actually of. For I do think that, unlike in these other areas, there’s an importantly <em>subjective</em>aspect involved in the appreciation of beauty that should not be ignored.

3:16: And finally, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

WH: I'm kind of notorious for cheating on anything that might be construed as a request for a desert island list, whether for American symphonies, sad movies, or philosophy books. But if I restrict myself to ethics and political philosophy and knock out everything before Hall's death in 1960, not only do I not have to mention that philosopher's brilliant works again, I can also ignore books by Hobbes, Rousseau, Austin, Mill, Trollope, Henry George, Herbert Croly, Charles Beard, Hans Kelsen, A.D. Lindsay, and W.D. Lamont, all of which have had some influence on my thinking about Value Theory or Democracy

And with those restrictions in place, I will (if still a bit reluctantly) narrow my list down to these five:

Harry Eckstein, Regarding Politics: Essays on Political Theory, Stability and Change.

Robert Dahl, Democracy and its Critics

Margaret Canovan, Populism

Ian Shapiro, The Moral Foundation of Politics

Nadia Urbinati, Representative Democracy: Principles and Genealogy

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

NEW: Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

NEW Josef Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised