Reading Beckett via Kit Fine (1)

Introduction

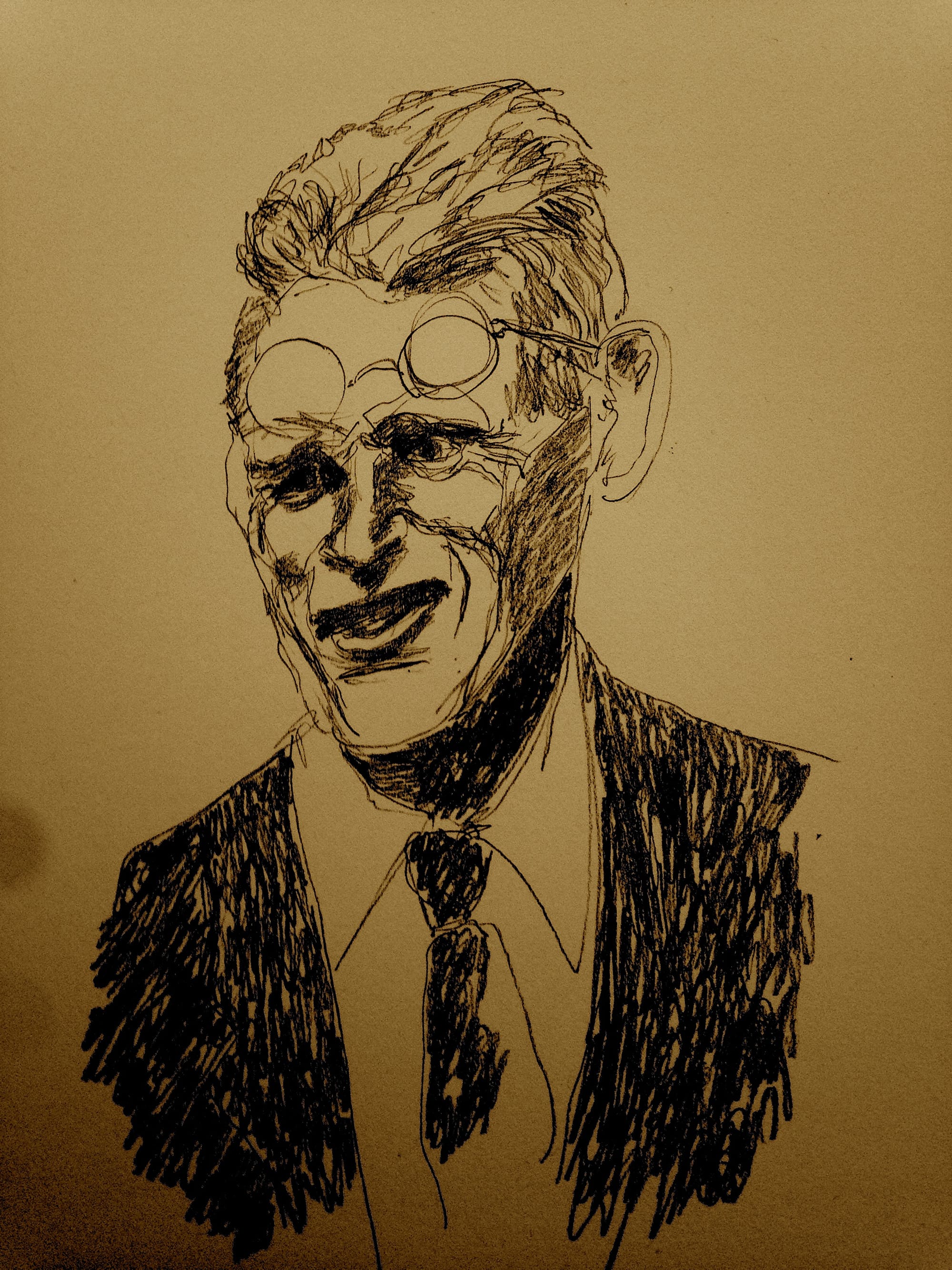

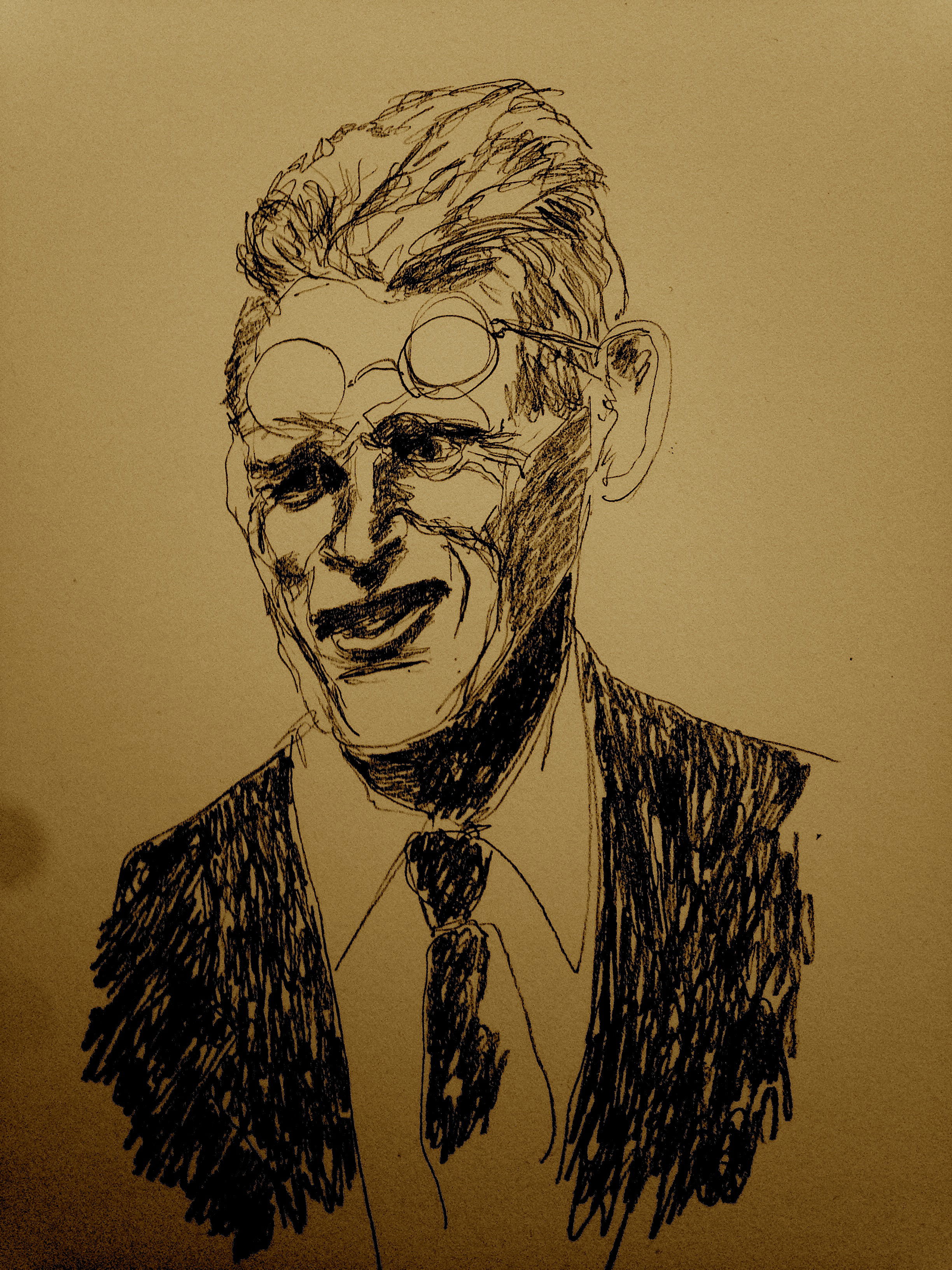

In 1920s London, a young Samuel Beckett engaged in psychoanalytic therapy with Wilfred Bion, a figure whose methods and temper would leave a lasting trace on both interviews and Beckett’s subsequent art. Although the therapy itself ended abruptly and never yielded what might be called personal transformation, it marked Beckett’s encounter with the limits of language and the unconscious, an encounter that would become structural in his writing.

Psychoanalysis, especially in its classical Freudian mode, posits that the speaking subject can be made coextensive with their speech through the talking cure: that what is unconscious can be made conscious by articulation. What Beckett experienced in those sessions was precisely the failure of that premise: a point at which therapy could not complete itself. In his fiction and drama, Beckett returns obsessively to situations where the attempt to speak becomes entangled with what cannot be spoken. The famous letter in which he says language appears to him “like a veil which one has to tear apart in order to get to those things (or the nothingness) lying behind it” reflects a lived recognition that the speaking self is never identical with what speech might be taken to represent.

From a structural perspective, this position problematises the assumption that representation and content can ever coincide. Psychoanalysis, in ideal form, desires to map the unconscious content onto articulated speech. Beckett’s art rehearses the breakdown of this mapping: characters speak, but the content often reasserts itself as something other than what is articulated. In terminology we’ve been developing, language in Beckett fails to ground what it implicitly names. The attempt to bring the unconscious into the realm of discourse is perpetually deferred.

This is not a failure of technique. It is the essence of his project. Beckett’s lived psychic experience, his intrauterine regression, his fears of containment and enclosure, was transposed onto stage and text not as veneer but as structure. Beckett’s therapy assisted him back into memories of the womb as trauma. The birth image that recurs in his work (e.g. Not I, That Time, Breath) is not a narrative motif but an operative constraint, a structural condition in which language is always already inadequate. Beckett’s text is not “about” unconscious content in the psychological sense, but about the non-compossibility of speaking content fully.

Language is not a transparent medium. It is a veil, but one whose perforations are themselves the scene of the work’s being. The veil cannot be lifted; it can only be drilled, as Beckett says, one hole at a time. Thus the first step in a deep introduction is to recognise that Beckett’s engagement with psychotherapy was not a biographical footnote, but the occasion of a discovery: the discovery that language, the primacy of the speaking subject, and the apparatus of psychology are all caught in a loop of partial articulation and residual opacity. The unconscious, in Beckett’s hands, is never something that can be annexed to speech. It structures speech’s failure.

Beckett’s encounter with Otto Rank’s idea of birth trauma, that the wound of being born is the ultimate psychical residue, is especially significant because it exposes the crack between bodies and language. Beckett read these theories deeply, even after psychoanalysis itself proved insufficient as therapy. Where standard psychoanalytic models envision a path from unconscious to conscious through speech, Beckett’s texts act as a constant return to the threshold where such a translation fails. In structural terms, this threshold is a liminal zone across which representation cannot safely pass.

The womb in Beckett’s theater is not a place of nurturance. It is a space of constraint , a closed system whose identity conditions do not permit a smooth passage to narrative coherence or inner access. This is not psychoanalytic imagery, but a structural constraint on the relation between part (speech) and whole (self, world, event). Thus the birth/trauma imagery in Beckett is not a symbol of trauma but an operative constraint that shapes the grounding relations in his art. Normally, we assume that parts ground wholes, that sentences ground propositions, that propositions ground meanings, that meanings ground subjectivity. Beckett reverses this: the whole (a world where representation cannot be complete) explains why the parts (sentence, voice, body) cannot be fully transparent to themselves.

This is why his texts feel like loops of repetition and revision rather than linear narratives of cause and resolution. This reveals why certain thematic pairs, presence/absence, visible/invisible, speech/silence, movement/stillness, keep collapsing into one another in Beckett’s work. The threshold that defined psychoanalytic hope, the possibility that speaking could produce wholeness, becomes in Beckett a place of persistent non-compossibility: two conditions that cannot be realised together within the same structural constraints. Speech cannot fully represent the self and preserve the conditions of linguistic failure at the same time. This is not an aesthetic preference but a structural identity condition. Beckett’s own quote about language as a veil to be drilled into but never torn away captures this. The attempt to puncture the veil is not meant to produce transparency. It is meant to reveal that behind the veil there is no transcendental content waiting to be liberated. There is only another layer of constraint.

This is why his characters often speak in loops, repetitions, corrections, self-interrogations. The text grounds its own inadequacy. This maps directly onto the notion of looping explanation: a situation in which explanation returns to its starting point because the system being explained does not permit a simple hierarchical grounding of parts under a single law. In Beckett’s dramatic works, the act of speaking explains the structure of seeing, and the act of seeing explains the constraint on speaking. Each explanatory pass revises the conditions of admissibility without closing them. This is the loop Beckett inhabits and dramatises.

Beckett’s encounter with psychotherapy, birth trauma theories, and the limits of language oriented his practice toward zones of non-closure and foundational inadequacy, and helps frame why this matters for criticism at large.

[Next - Grounding, Non-Compossibility, Looping]