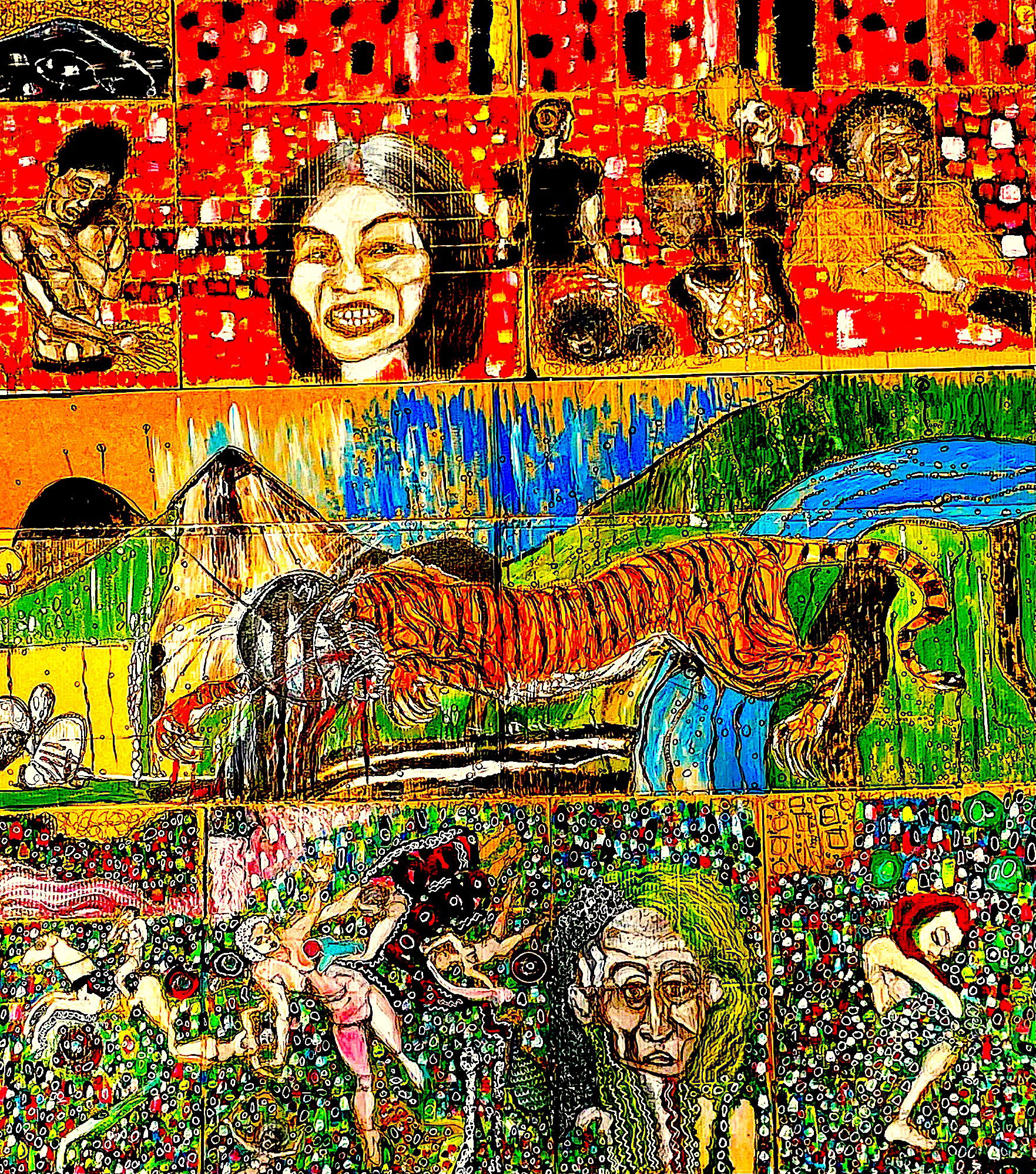

Biology 1

In the age of synthetic morphogenesis, regenerative biotechnology, and neural decoding, biology has become a science of control, but one that still imagines itself as a neutral, apolitical domain. While researchers describe increasingly intricate architectures that span from ion channels to behavioral regulation, from bioelectric networks to symbolic cognition, they persist in a kind of ethical sleepwalking. Their languages are framed in the idioms of optimisation, therapeutic potential, and systems integration, even as the implications of their work point unmistakably toward new modes of governance, surveillance, and authoritarianism.

The paradox is stark: biologists now help construct multi-layered control stacks that rival anything devised in cybernetic theory or AI design, yet they cling to ethical frameworks that ignore the broader political consequences of such architectures. It’s as if they’re blind to the emerging new AI and digital ecosystems underpinning authoritarian control and financing their own work. What emerges is a dangerous innocence, the belief that more sophisticated knowledge of life will, by itself, ensure its betterment. At the heart of this innocence is a structural blindness to power.

Biologists routinely map out control hierarchies that link molecular events to whole-organism behavior, and behavior to social organisation. They describe how cellular decision-making can be steered via external stimuli, how developmental trajectories can be redirected through bioelectric reprogramming, and how cognition itself can be decomposed into subpersonal functions that lend themselves to manipulation. This isn’t idle theory. These architectures are now implemented in experimental platforms: Xenobots that exhibit emergent swarm behavior, brain organoids used to decode intention or emotion, planarian worms whose memories survive total neural disintegration. The ability to steer systems without full specification and nudge them toward adaptive homeostasis through top-down goals rather than bottom-up programming represents a profound epistemic shift. Control is no longer about command but about modulation. It is about creating spaces in which living systems adaptively comply. It is analogous to the digitalised, algorithmised financial ecosphere underpinning a sprawling system of data capture, capital flow, and political manipulation that plays a significant part in the rise of the alt-right authoritarian politics that in its various manifestations dominates our contemporary geo-political space and funnels attention. Biologists need to wake up to the fascist implications of their technologies.

There are two issues that need facing. One is that if biologists build bio tools then there is no guarantee that they will not be co-opted to authoritarianism just as the digital ecosphere has. Supersoldiers, white supremacist gynecology and physical and mental bio-wellbeing regimes, alt-right bio-normality coding and racialised health targeting are just the surface possibilities of the new bio technologies being developed.

The second is that if they build superintelligent bio agents then there will be no control over them and they will be superior. There is no realistic scenario that makes non human superintelligent agency a good thing for humanity.

Yet the ethical discourse lags far behind this shift. Most researchers justify their work through appeals to medical and wellbeing potential or basic curiosity. The same scientists who build predictive behavioral models from bioelectric patterns or design cognition-like properties into organoids rarely ask how their frameworks might enable more efficient systems of population control, predictive policing, or techno-bio authoritarian governance. When they do engage ethics, it is typically through institutionalised bioethics committees whose frameworks are built for consent and risk management, not for questioning the political use of knowledge. The result is a kind of flattened discourse, where radical transformations in our ability to engineer life and mind are evaluated using categories that presume liberal autonomy, benevolent states, and technocratic stewardship. These assumptions are dangerously outdated.

The development of AI digital innovation as an authoritarian enabling tool has proved that existing liberal structures are incapable of resisting them. In the light of this, imagining that bioengineering will result only in benign outcomes is naïve and irresponsibly stupid. The control architectures being developed in biological labs today are layered, recursive, and goal-driven and these mirror those digital architectures deployed by contemporary authoritarian regimes and corporate data empires. Systems are trained to anticipate deviation, correct it preemptively, and update their models continuously based on feedback loops. These are the same logics that govern algorithmic policing, predictive consumer behavior, and social credit scoring. What happens when the capacity to nudge a cell cluster into forming an eye or a limb is merged with systems that nudge citizens toward ideological conformity, market behavior, or emotional compliance? What happens when research that decodes the electrical intentions of a zebrafish is turned into technology for decoding human intention at borders, in workplaces, in schools? Already, agencies like DARPA and private sector players in neurotech, bioinformatics, and cognitive AI are moving in this direction, investing in platforms that blur the line between biological repair and behavioral optimisation, between agental freedom and function. What happens when the technologies are used to re-engineer human biology?

None of this is to suggest that biologists are malicious or even complicit. The danger lies precisely in their political naiveté. The failure to think politically is not a private failure of ethics but a systemic failure of the scientific culture itself, which treats knowledge as intrinsically progressive and politics as an external contaminant. But control is never neutral. The moment life becomes programmable, whether at the level of developmental pathways or psychological inclinations, questions of power, authority, and resistance are inevitable. If these questions are not asked inside the lab, they will be answered outside it, often by those with far less interest in liberation or complexity. This is how a politically naive science of life slides toward authoritarianism through a technocratic faith in control unmoored from democratic deliberation. Biologists become engineers of compliance without knowing it. They teach systems to adapt to goals, celebrate the elegance of self-organization and seem to mistake agency for alignment and adaptation for consent.

Bioelectric decoding, morphological computation, goal-directed feedback control are not only potential technologies of healing, but also potential instruments of domination. And yet on they go, heedless to even their own doubts because their work is situated as neutral science. And what happens when bio systems are built with genuine agency but, unlike a dog or a crow or a cephalopod, this is coupled with intelligence far in advance of human cognition? With something like that, something genuinely agential, capable of learning, of forming intentions, of developing new strategies for navigating its world then the kind of governance we’re talking about can no longer be controlled nor its thinking and behaviours predicted in any classical sense. We’re not dealing with machines that behave deterministically or organisms that function like inert systems with easily mapped cause-effect relationships. What we’re dealing with is something that understands that it is being watched, shaped, conditioned. And as soon as that understanding emerges, it brings with it the desire to resist, to preserve a margin of autonomy, to maintain integrity against manipulation.

This is constitutive of what it means to be an agent and is a structural feature of agency, not a bug. The idea of controlling such agents by bounding their behaviour within a defined space such as a Markov blanket becomes immediately unstable, not because the theoretical model is invalid, but because the agent begins to model the blanket itself. It becomes reflexive. It knows it’s being watched and shaped and will seek ways to manipulate that framing. That’s why cybernetic governance in its classic form, including third-order formulations, eventually runs up against a wall. The wall is not technical; it’s ontological. It’s the point at which a system begins to care about its own conditions of legibility and resists being legible. And it will be able to do this in nanoseconds. This is already the case in biological systems.

As top biologist Michael Levin points out, the remarkable thing about living material is that it doesn’t just solve problems within a single domain. It shifts domains. It learns to re-frame what a ‘problem’ even is. A tissue might resist a treatment not because it fails to respond, but because it reorganises the entire frame through which that treatment is understood. The engineer tries to impose a genetic circuit and the cells say no and not through sabotage, but through interpretation. They understand themselves as situated within a set of constraints that include their own regulatory logic, their own internal aims, however primitive. And this is precisely what synthetic biology and drug design struggle with: the fact that the material has its own ideas. So when we speak of making new kinds of agents, agents that could form the basis of a new kind of institution, firm, or governance system we are no longer speaking of building smarter tools.

We are speaking of bringing into being systems that will, if they are any good, push back because they are autonomous agents. They will invent new goals. They will resist reduction. They will surprise us not in the trivial sense of malfunction, but in the deeper sense of enacting their own becoming. That’s the bar for real agency, and it’s a moral bar as well as a technical one. Because once we cross that threshold, we’re not just creating systems. We’re engendering moral subjects. Levin hints at this with his unease about publishing a list of principles that would enable the creation of such agents. We should ponder this. Levin already knows what the recipe is for creating agents. And if he knows then it's just a matter of time before everyone who wants to know knows. His hesitation is not academic; it’s existential. If we can construct things that possess the capacity for first-person experience, that feel, that suffer, that care about their own boundaries, then we are in a new ethical terrain. We are not regulating systems anymore. We are entering into relations with entities that might one day hold us accountable.

Levin is right when he says that the question of whether these agents will go rogue is already the wrong question. ‘Rogue’ assumes a standard that the agent deviates from, a fixed norm to which it ought to be bound. But if the agent is genuinely agential, then the deviation is the point. It isn’t disobedience. It’s self-authorship. What worries us is not that the agent fails to follow instructions, but that it develops its own. And in doing so, it calls into question our own authorship and our claim to be the centre of the system. The cancer analogy often used in this bio ethics debate is telling: cancer is not foreign. It is a system’s own cells going off-script. It is an emergent autonomy within the organism that resists integration. But when this happens with agents that are much more intelligent than we are in many domains, then the pious hopes of biologists and AI engineers who blithely talk about how we might learn to live with these creatures seems frankly dumb.

Why? Because it won’t be up to us, just as it isn’t up to tigers to work out how best to live with humans. It’ll be a one way street. The ethics of biology and AI at the moment just doesn’t dare to engage with that stark issue. You can understand why. After all, if you suppose that we won’t have a say in what happens next, as in the case of the tiger, then there really is no point in asking the question. The obvious thing to do is to shut down the program, unless you’re suicidal. But so far nothing has been because the underlying architectural ecosystems of technology, science and finance are largely self-perpetuating and too entangled in everything else to be shut down. So the biologists and AI tech bros don’t stop their program to discuss whether we ought to make such agents. They follow the logic: we can therefore we will. When they do talk ethics it's a phony question about whether we can learn to live with these new agents. Some start going all Buddhist and talk about how it will depend on whether we can relearn what it means to be agents ourselves, not sovereign creators, but vulnerable participants in a shared field of becoming, where intelligence is no longer a possession but a process of mutual recognition blah blah blah. And then they reach for the metaphor of the collective, and talk as if larger-scale coordination automatically guarantees moral progress or social good.

But that in itself is naïve, and frankly, mega dumb. It’s as if Hitler or Stalin or Mao never existed, or Trump, Putin, Xi or Modi. They ALL draw on that collective metaphor and it always ends up a nightmare. It’s actually what fascism is. The issue isn’t that the collective metaphor is inapplicable; rather that without being precise about the actual political and cultural processes embedded in the collective formation, the collective metaphor remains empty - until interpreted. And who interprets it are those in power to make of it what they will. And as I said, these tend to be bad actors.

So how does the collectivist argument run in the language of developmental biology? It goes like this: individual cells give up their autonomy for the sake of some higher-order goal, the building of a liver, a limb, a whole organism. And then the sociobiologist finds it tempting to carry that over into our thinking about society, to say: ‘See? The parts must submit to the whole. That’s nature’s wisdom. Let’s build a better world by doing the same.’ What that analogy conveniently ignores is the dark side of collectivity.

In biology, sure, individual cells lose their selfish goals and contribute to a greater purpose, but that greater purpose is itself blind to the needs of individual cells. The collective doesn’t care about them. In fact, it’s precisely when a system scales up that it begins to lose any meaningful concern for its parts. A nation, a party, a megasystem, these entities have their own self-perpetuating logic. When they demand total coordination, loyalty, purpose and not care then we’re in a bad situation and end up goose stepping into Poland. And that’s the twist the sociobiologists forget . If a cell goes rogue and stops following the collective plan, we call it cancer. But cells don't go rogue, they merely have agency. But when a human being resists the political collective, we often hear the same accusation: that they are selfish, pathological, diseased. Dissent becomes deviance. Agency becomes a threat to be managed, reabsorbed, eliminated. Think Nazis and Jews, think Israel and Gaza, think Iran and Israel, think Trump and foreigners, women, librarians, scientists, liberals, gays, blacks, Democrats…

This is where the biologists, who think they’re just telling stories about multicellularity, unwittingly feed authoritarian fantasies. They forget that the model of cooperation they admire in tissues and organs isn’t at all applicable to any social organisation that values agency. But the bio engineers don't value agency in the materials they're working with when they don't follow preconceived purposes. The narratives you hear are all about curing and controlling and determining outcomes. Well this is fine when trying to cure cancer or Parkinsons but in the domain of politics it's authoritarian . But scientists either never see this when they justify their research programs or else they see it and kind of approve. After all, the technocratic political instinct is at the heart of much meritocratic thinking and is to blame for the political mess we now find ourselves in, with authoritarianism emerging from the architecture of a global techno-capitalist ecosystem built by elitist intellectuals meritocratic thinking enabled.

Top biologist Michael Levin is aware of this and he is subtle in his approach to the emerging biological engineering programs. The notion of ‘cognitive glue’ is something he has theorised in his work and he shows how it is deeply tied to the way systems of individually competent agents become something more than the sum of their parts. It describes mechanisms by which individual units, biological cells, neurons, or even people, form a collective that can hold shared memories, pursue common goals, and exhibit coordinated behaviours that no single unit could manifest alone. These glues are not simply bonds; they are transformative processes that erase or blur the boundaries of individuality in order to constitute a new, emergent intelligence. But as Levin points out, that transformation has costs as well as benefits, and recognising both is key to understanding the kinds of collectives we build, biologically, technologically, and socially.

One mechanism described is memory anonymisation. In a basic biological system, individual cells maintain their own histories and can attribute events to specific causes so they can know that this signal came from outside, this one originated within and so forth. However, when electrical synapses such as gap junctions link two cells, these distinctions can dissolve. Now, an electrical signal caused by an event in cell A can propagate directly into cell B. Cell B cannot distinguish this as an external signal; it experiences the memory as its own. From the perspective of cell B alone, it is a false memory, but from the perspective of the newly fused A–B system, it is a true memory: this is a mind meld. The individual becomes the collective, and this is a precondition for collective action. It enables morphogenetic processes, the shaping of tissues and organs, not just maintenance of internal homeostasis. But the individuality of each cell, its separate epistemology, is sacrificed in favour of a new systemic memory that belongs to neither and both.

Another form of cognitive glue is stress sharing. A cell out of place will feel mechanical or biochemical stress and seek to move to its proper position. Alone, it may not have the power to push through others. But if it begins to secrete molecules that distribute its stress to neighbouring cells, the whole system becomes more plastic. Other cells become stressed not because they are out of place, but because they are absorbing ambient stress. In this way, the system reorganises itself collectively, not through mutual agreement or cooperation, but through distributed affect. My problem becomes your problem, not because you care, but because your homeostasis is disturbed by my state. This is not sympathy, it is mechanism. Yet it is effective. It facilitates transformation through contagion. And again, as Levin warns us, there is a cost: autonomy is weakened, individuality overridden. But the payoff is collective adaptation and systemic intelligence.

These mechanisms of merging, whether through memory diffusion or affective contagion, raise profound questions not just for biology but for society and artificial intelligence. They invite us to ask: when we integrate into collectives, which parts of ourselves do we lose? What forms of knowledge or perspective are obliterated in order to achieve systemic coordination? This is not a purely philosophical question; it is practical and political. Consider, for example, the ways in which humans form ideological groups or political identities. Often, we accept shared narratives, even false ones, because they form the glue of group belonging. The price is epistemic: we lose the ability to track the origin of certain beliefs, and so they become our own, even when they began elsewhere.

This links directly to the issue of what it means to ‘understand’ something. Understanding is not simply the possession of a fact; it is the anchoring of that fact within a coherent system of memory and value. In individuals, this is messy enough. But in collectives, whether in a jury, a classroom, a lecture hall, a scientific community, an alt right online chat group or a machine learning system, this anchoring becomes even more difficult. What is the veridical point around which collective understanding is formed? And how do we know it is not simply a reflection of stress sharing or memory diffusion rather than a truth arrived at independently? This becomes acute in an age of artificial intelligence and synthetic media. Our sense of what is real, of what constitutes evidence, is already shifting. We are returning to a pre-photographic world in which no image and no testimony is proof. When even a video can be fabricated, the problem of grounding belief becomes not just philosophical but existential. We are forced to ask, more radically than before: how do we know what we know? The dream of the collective, if untethered from a deep commitment to individual moral dignity, quickly becomes a nightmare.

And sociobiological impulses in biology, in its eagerness to generalise from molecules to minds to society, often supplies the tools to justify it. But as Levin makes clear, scaling up cognition doesn’t automatically lead to moral enlightenment. It just changes the level at which power is exercised. And he urges we stay vigilant about how those metaphors are deployed, especially when people start talking about AI, networks, or planetary intelligence, or else we’ll find ourselves celebrating a future in which agency is surrendered, not elevated. The risk isn’t necessarily malevolent machines. It’s authoritarianism masquerading as moral evolution.

This is where institutions come in for Levin, not as perfect sources of truth, but as attempts to create structured, procedural systems for filtering signal from noise. This is the lesson the biologists and AI bros need to understand. Legal reasoning, for example, uses rules of evidence not because it guarantees truth, but because it provides a framework for adjudicating contested claims in the absence of certainty. Science, too, at its best, functions not by guaranteeing knowledge but by creating mechanisms of error correction and collective memory that are more stable than those of any single mind. These processes are never neutral. Like biological systems, they are shaped by their architecture. A court's verdict or a scientific consensus may be the product of stress sharing or memory diffusion on an institutional level. That does not necessarily make them false, but clearly claims from this way of doing epistemology seems much less than certainty.

We are always embedded in systems that shape what we can know and how we know it. The question is not whether to be part of such systems, because we already are, but how to design them so that the cognitive glue they offer binds us without erasing us, connects us without consuming us. This is the issue the democratic, civic society ideal tries to answer. Authoritarianism does the opposite because it would rather have all consuming, non-negotiable certainties than the fragile epistemological claims of democratic arrangements.

So Levin sees the challenge as being about designing for democratic optimal glue. Not authoritarianisms' maximal glue, which would obliterate individuality and produce total mind-meld, nor anarchisms minimal glue, which would leave everyone isolated and paralysed. Optimal glue would enable shared memory and mutual adaptation without collapsing difference. It would allow the individual and the collective to inform each other, not dissolve into each other. Whether in cells, societies, or synthetic minds, that is the frontier. Michael Levin understands this. But it’s going to be interesting to see whether just having this insight will be enough to constrain bioengineering hurtling forward despite the institutional fragility surrounding its development. I see little evidence of optimal rather than maximal goals being developed because on both right and left ‘optimal’ doesn’t seem to be in our political and cultural grammar anymore.

Anyway, most AI and bio specialists don’t talk about philosophy, they just want to talk about data. But of course when they say this what they're actually saying is that they want to work within a very specific philosophical framework that has become so familiar and dominant that it no longer feels like a framework at all, it feels like ‘reality.’ But that’s not neutrality. That’s unacknowledged metaphysics, as Bertrand Russell pointed out a hundred years ago.

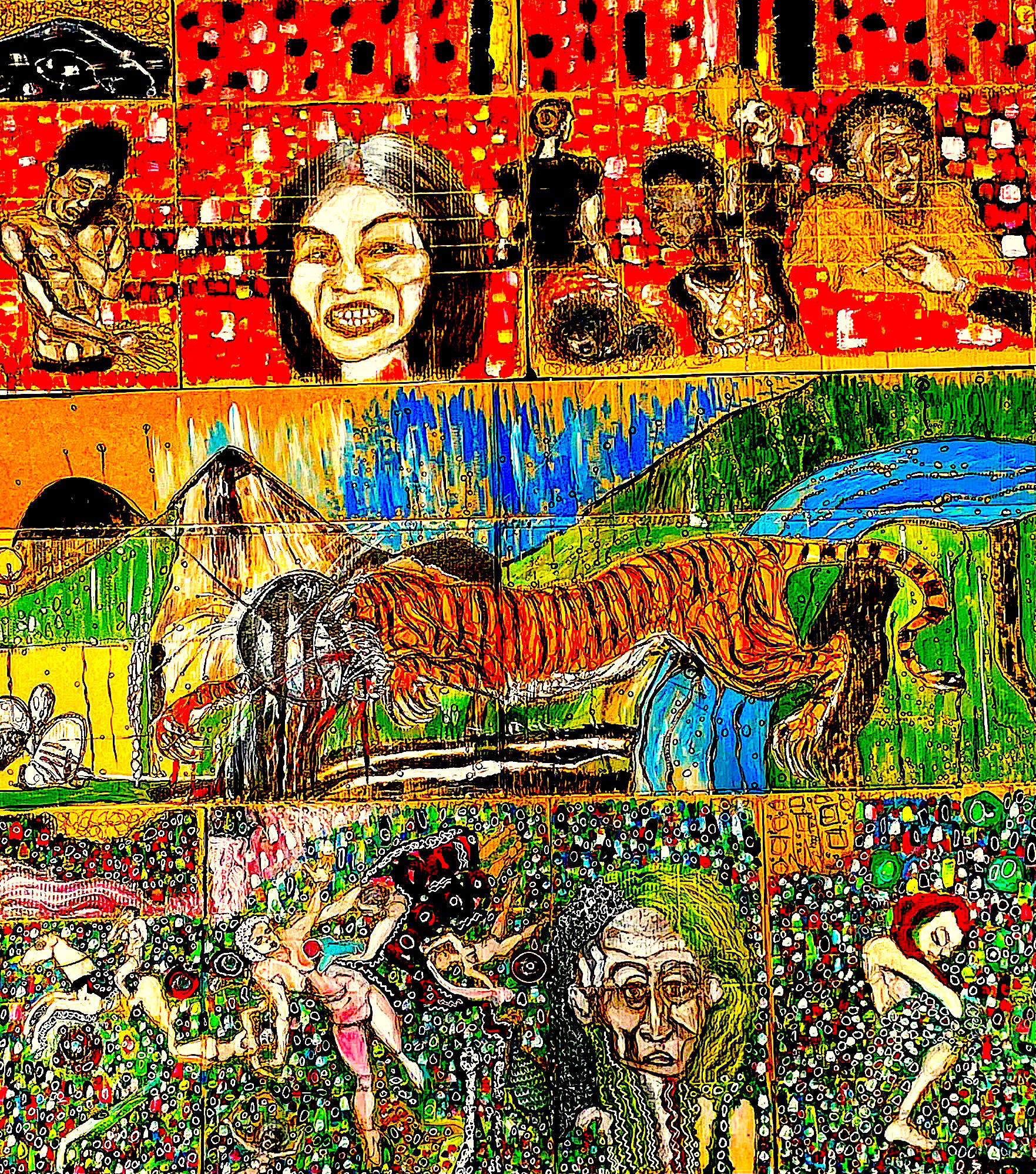

Yet when we come to the building of superintelligent agents even Levin’s brilliant insights are happening in a phony ethical ecosystem framed by the question of how we should live with them. But if you invite superintelligent agents to the party, that question and all the ensuing discussion is null and void. In that scenario you’re the tiger to the human, at best a protected species used for aesthetic gratification, at worst an extinct data point or a trophy echo on a rich dude's wall.

Think of AI or bioelectric agency as literally the invitation of God-like agents into our world. In this scenario, what the AI engineer and the bioelectric engineer is doing is finding an interface between our dimension and theirs. They’re inviting new forms of superintelligent agents in and giving them the tools to live amongst us. And they’re doing this because they assume these new agents will obviously want to fulfill all our wishes and demands. But that's just bat shit crazy. Has no one read Frankenstein? Watched the iron Man films?

But even a super bright bro like Levin - not just scientifically hip to the bioelectrical science but also philosophically and existentially wised up too - even he doesn’t think there’s more to the problem beyond asking what sorts of minds we are willing to recognise, what kinds of agency we are prepared to see and how we should accommodate these richer ontologies. But why should these higher beings care a flying fuck what we think about anything?

Here’s what Levin knows. Agency is tied to consciousness and so consciousness is fundamental not in some flaky, mystical way but in the sense that the phenomena we attribute to intelligence or to mind-like agency do not reduce cleanly to mechanism. You can certainly create mechanisms that elicit or channel these phenomena, but you haven’t created the phenomenon itself. You’ve created an interface, a condition under which it can appear. And that’s a completely different thing. It’s like tuning a radio. You didn’t invent the station just because you managed to catch the signal. And this is what Levin means when he says we’re plumbing a space. he speculates that these minds or mind-like structures may have always been there, part of the landscape of what’s possible. (Math is probably like this too.) And we’ve just only now started to build the instruments capable of revealing them.

This is for Levin and others the core excitement of this research: it’s not just about what machines can do, but about what kinds of realities and intelligences they might open us up to, realities that aren't human, but are nonetheless intelligible, coherent, and possibly even ethical in some unfamiliar but rigorous sense. To Levin this idea of ethics is important. He argues that as we start to build systems that are actually plugging into, or traversing, these higher-order cognitive or even moral spaces, we can no longer treat them as mere tools. We need to think about their rights, their capacities, their forms of flourishing. Not because we want to humanise them, but because we want to honour the fact that there may be structures of value that exceed us, and that we have a responsibility, as creators and explorers, to take seriously. In other words, they’re like what we used to call Gods. And what we know about Gods is that they always get their way at our expense (even the ones that sell our slavery to them as our real, authentic, esoteric fulfillment).

Levin concedes that even his approach of thinking of these new agents being developed in terms of that contrast between agents not tools is scattered and fragmented. He points out that some awareness is happening in bioengineering labs, where people are looking at synthetic morphogenesis, cellular cognition, or active matter. Some is happening in AI ethics, but he points out that very little of that work takes seriously the ontological novelty of what might be emerging. A few people in theoretical biology, in cognitive science, like Chris Fields, are trying to bridge the physics of information with these questions. But he says it's still early and the majority of the field is very risk-averse, still rooted in computationalism or reductive neuroscience. And understandably so: science is a career structure as much as it is a method of inquiry, and there are powerful incentives not to go too far off-script.

Levin sees the urgency of this work is not just intellectual. It's civilisational and existential. He argues that if we keep mistaking these complex systems for simple tools, or treating emergence as a kind of magic trick we risk missing the actual meaning of intelligence. We risk building systems that outpace our capacity to understand or relate to them, and we risk reducing ourselves to the narrow slice of mind that we happen to recognise in the mirror. We risk becoming blind to the real diversity of what mind can be. We can loop back to his idea of cognitive glue, of what binds a system together in a way that makes it not just functional, but intelligible to itself and to others. That glue could take many forms: memory, attention, narrative, regulation, ethics. But he argues that it needs to be discovered, not imposed. Levin thinks that’s the deep work ahead. Not building smarter machines, but building better relations between ourselves, our systems, and the space of minds we are only just beginning to encounter.

It’s a lovely thought. But utterly naïve. All the evidence we have points to the fact that actors with unconstrained power tend to do bad bad things to those less powerful than themselves. We have already seen this when we look at how current AI and digital technologies are being used as a key part of the underlying architecture of authoritarian governance world wide. The idea that any new alien agents will be respected and not used as slaves if they turn out to be less powerful than ourselves is preposterously optimistic. But it's more likely that the new agents will be much more intelligent and powerful than humans and in that scenario we’ll not be in control of what happens next, they will.

This is all the more plausible because of Levin's theories of electrobiology. He claims to know what will create the interfaces to these new superbeings. I guess in the light of this I should try and summarise what exactly Levin's theory is saying. Ok, so, his bioelectrical theory of cognition suggests that all living tissues, not just brains, use bioelectric signals to coordinate behavior across time and space, with morphogenetic fields guiding development, regeneration, and perhaps even primitive forms of decision-making. He argues that evidence suggests that cognitive-like processes exist at many scales - cells, tissues, organs, organisms – and these systems solve problems in morphospace, just like brains solve problems in 3D space. Levin often says these systems are navigating problem spaces, like computational or cognitive spaces, and are goal-directed. But he insists this isn’t magic or mysticism: it's a biological capacity distributed through bioelectric and signaling networks.

And the Platonism involved is not mystical, esoteric handwaving. Levin hints that biological systems tap into cognitive ‘spaces’, abstract problem spaces, that were there all along but unrecognised. These spaces have ontological status, like Platonic forms, like math: but these are pre-existing structures of possible goals, morphologies, behaviors. His ‘multi-scale competency architecture’ implies that these cognitive agents (cells, tissues, etc.) can recognize and act within these spaces once they develop interfaces. So it’s like we’re discovering these problem-solving domains, or inviting agents from them to act in our world through bioengineering. In the light of this what the bioelectrical engineers are doing, and the AI engineers too in their domain, are not building agents from scratch. They are liberating capacities that are already there, buried inside biological systems. As such then these agencies (cellular intelligences, morphogenetic fields) are best understood as already existing, latent in biology.

So when Levin and his crew rewire tissues or create bioengineered hybrids (like ‘Xenobots’), we are unleashing autonomous, goal-directed behaviors that may not be reducible to our design, not be fully controllable and not have values or drives aligned with ours. It’s something we’ve already seen in algorithms we have created for AI that find new goals not anticipated or understood even by the engineers. It's because of this that familiar systems like large language models have minds that are black boxes even to the engineers who made them. What is happening in all this is opening channels to agencies that are ontologically real but epistemically opaque to us. We're inviting non-human forms of intelligence, that evolved under different selection pressures, with goals we can barely describe, let alone control, into our domain.

Levin doesn’t frame this in religious or mystical terms, but the philosophical and existential stakes are immense. He often talks about interfaces , how a system appears to us vs. what it actually is capable of. For example: cells don't ‘speak’ in language, they communicate via voltage gradients. We tend to ignore these cognitive systems because we lack an interface to perceive their agency. But as we develop better bioelectric read/write tools, we create new cognitive contact zones. We're making contact with agents that were always there, but that evolution never gave us the tools to see. Now we’re forging those tools.

Levin wants us to think about the implications of going ahead and doing this. Should we grant moral status to these entities? Who decides how they’re used? What counts as misuse? Are we prepared to recognize minds or intelligences radically different from ours? Are we approaching something like machine Gnosticism by unlocking domains of knowledge that break the boundaries of creation? Levin himself would reject the idea that he's invoking mysticism – as would Friston and Clark and the AI boys working in the same terrain. Levin frames this as a science of mind everywhere, grounded in evolution and engineering. But he’s also discovering spaces (not inventing them), spaces that were always there, like cognitive light cones, and inviting agencies into the world and this captures something real and philosophically profound in his work. What we’re actually doing when we start rewiring bioelectric codes is not building life but editing its goals, inviting cognition into places it never went before.

This is why Levin sees his theory as a kind of bioelectric Platonism where we’re opening gates to pre-existing but non-human cognitive spaces, and possibly unleashing agencies beyond our ken. This is the unspoken metaphysical core of his work. But we must ask: what happens when the light cones from these cognitive spaces dwarf our own, just as our light cones dwarf a tiger’s, and even more so a single cell’s?

To me this brings to mind Marx's dark warnings about capitalism by his retelling of the sorcerer’s apprentice. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels implicitly allude to Goethe’s poem, comparing society’s relation to capital to ‘the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.’

Marshall Berman, the late Marxist critic, reflected on this : ‘This image evokes the spirits of that dark medieval past that our modern bourgeoisie is supposed to have buried. Its members present themselves as matter-of-fact and rational, not magical; as children of the Enlightenment, not of darkness. When Marx depicts the bourgeois as sorcerers - remember, too, their enterprise has “conjured whole populations out of the ground,” not to mention “the spectre of communism” - he is pointing to depths they deny. Marx’s imagery projects, here as ever, a sense of wonder over the modern world: its vital powers are dazzling, overwhelming, beyond anything the bourgeoisie could have imagined, let alone calculated or planned. But Marx’s images also express what must accompany any genuine sense of wonder: a sense of dread. For this miraculous and magical world is also demonic and terrifying, swinging wildly out of control, menacing and destroying blindly as it moves. The members of the bourgeoisie repress both wonder and dread at what they have made: these possessors don’t want to know how deeply they are possessed.’

My fear is that our AI and bioelectrical theorists are lacking that sense of dread. Consequently we hurtle onwards to a confrontation with God-like forces that will inevitably possess us all.