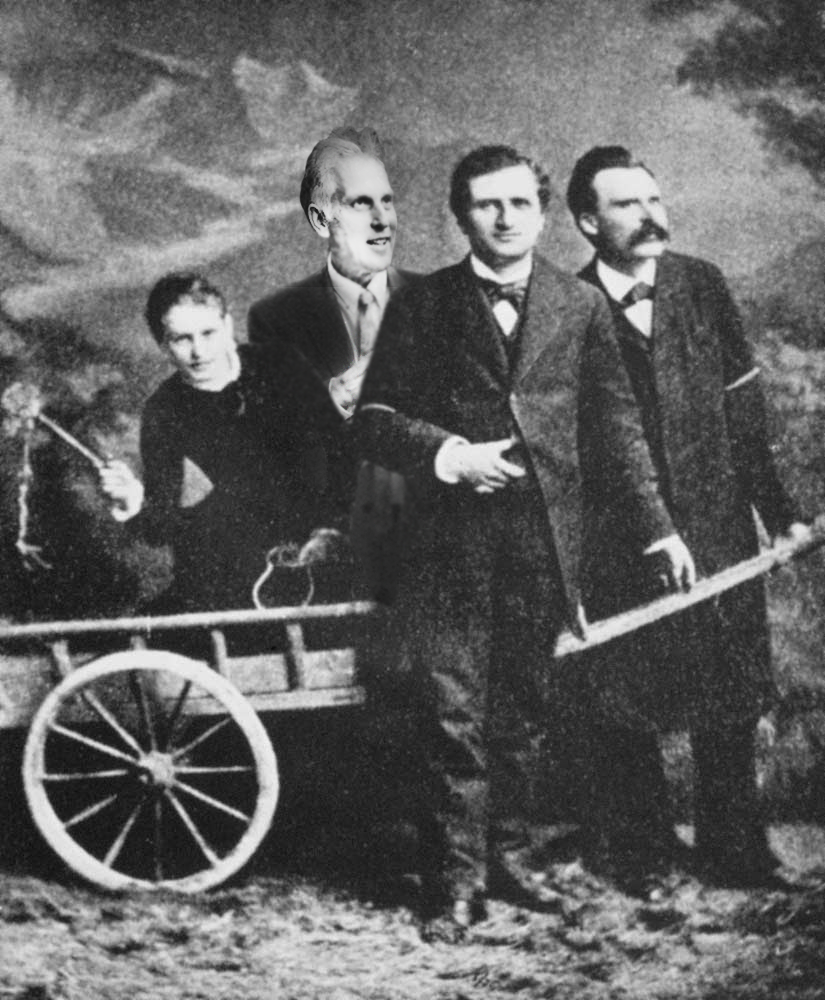

Exclusive 3:16 Interview with Soren Kierkegaard

Interview by Richard Marshall

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard is a profound and prolific writer and public intellectual in the Danish “golden age” of intellectual and artistic activity. His work crosses the boundaries of philosophy, theology, psychology, literary criticism, devotional literature and fiction. Kierkegaard brings this potent mixture of discourses to bear as social critique and for the purpose of renewing Christian faith within Christendom. At the same time he makes many original conceptual contributions to each of the disciplines he employed. He is known as the “father of existentialism”, but at least as important are his critiques of Hegel and of the German romantics, his contributions to the development of modernism, his stylistic experimentation, his vivid re-presentation of biblical figures to bring out their modern relevance, his invention of key concepts which have been explored and redeployed by thinkers ever since, his interventions in contemporary Danish church politics, and his fervent attempts to analyse and revitalise Christian faith.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Soren Kierkegaard: Oh Richard, it isn't at all difficult for philosophy to begin. Far from it: it begins with nothing and can accordingly always begin. What seems so difficult to philosophy and the philosophers is to stop.

3:16: Is philosophy just fear and trembling?

SK: Philosophy is life’s dry nurse, it can look after us but not give suck.

3:16: What do you mean?

SK: So, marry, and you will regret it; don’t marry, you will also regret it; marry or don’t marry, you will regret it either way. Laugh at the world’s foolishness, you will regret it; weep over it, you will regret that too; laugh at the world’s foolishness or weep over it, you will regret both. Believe a woman, you will regret it; believe her not, you will also regret it… Hang yourself, you will regret it; do not hang yourself, and you will regret that too; hang yourself or don’t hang yourself, you’ll regret it either way; whether you hang yourself or do not hang yourself, you will regret both. This, gentlemen, is the essence of all philosophy. Philosophy cannot and should not give us an account of faith, but should understand itself and know just what it has indeed to offer, without taking anything away, least of all cheating people out of something by making them think it is nothing.

3:16: You like your paradoxes don’t you Soren?

SK: A fire broke out backstage in a theatre. The clown came out to warn the public; they thought it was a joke and applauded. He repeated it; the acclaim was even greater. I think that's just how the world will come to an end: to general applause from wits who believe it's a joke. So Richard, what if everything in the world were a misunderstanding, what if laughter were really tears?

3:16: Who am I? why am I alive? who is responsible for me? how should I be human? all that existential stuff, that's your thing isn’t it? You're full of those heavy duty puzzlers aren't you?

SK: This is the issue: How did I get into the world? Why was I not asked about it and why was I not informed of the rules and regulations but just thrust into the ranks as if I had been bought by a peddling shanghaier of human beings? How did I get involved in this big enterprise called actuality? Why should I be involved? Isn't it a matter of choice? And if I am compelled to be involved, where is the manager—I have something to say about this. Is there no manager? To whom shall I make my complaint?

3:16: You sound like Jerry Seinfeld! Are you looking for the truth? Philosophers do that a lot?

SK: No, it is perhaps the misfortune of my life that I am interested in far too much but not decisively in any one thing; all my interests are not subordinated in one but stand on an equal footing.

3:16: So you’re not after truth but something worth living for, or dying for?

SK: Yes. The thing is to understand myself: the thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live and die. That is what I now recognize as the most important thing. You should put down that beer and try it Richard.

3:16: So you don’t think life’s about finding a little happiness wherever it can be found?

SK: Listen to the cry of a woman in labor at the hour of giving birth Richard — look at the dying man’s struggle at his last extremity, and then tell me whether something that begins and ends thus could be intended for enjoyment. Do you not know that there comes a midnight hour when every one has to throw off his mask? Do you believe that life will always let itself be mocked?

3:16: Don’t you think the world is a bit much and it’s useful to be able to distract oneself? Is self deceit not a better option than facing these deep horrible truths about living?

SK: Bah! Do you think you can slip away a little before midnight in order to avoid this? Or are you not terrified by it? I have seen men in real life who so long deceived others that at last their true nature could not reveal itself; In every man there is something which to a certain degree prevents him from becoming perfectly transparent to himself; and this may be the case in so high a degree, he may be so inexplicably woven into relationships of life which extend far beyond himself that he almost cannot reveal himself. But he who cannot reveal himself cannot love, and he who cannot love is the most unhappy man of all.

3:16: But you laugh? You seem to agree with those who say that the only intelligent tactical response to life’s horror is to laugh defiantly at it.

SK: When I became an adult, when I opened my eyes and saw actuality, then I started to laugh and have never stopped laughing since that time. I saw that the meaning of life was to make a living, its goal to become a councilor, that the rich delight of love was to acquire a well-to-do girl, that the blessedness of friendship was to help each other in financial difficulties, that wisdom was whatever the majority assumed it to be, that enthusiasm was to give a speech, that courage was to risk being fined ten dollars, that cordiality was to say "May it do you good" after a meal, that piety was to go to communion once a year. This I saw, and I laughed.

3:16: But there’s a buzz to be had from the chance encounter, the unusual, the unplanned isn’t there? Isn’t that what makes life interesting?

SK: You love the accidental Richard. A smile from a pretty girl in an interesting situation, a stolen glance, that is what you are hunting for, that is a motif for your aimless fantasy. You who always pride yourself on being an observateur must, in return, put up with becoming an object of observation. Ah, you are a strange fellow Richard, one moment a child, the next an old man; one moment you are thinking most earnestly about the most important scholarly problems, how you will devote your life to them, and the next you are a lovesick fool.

3:16: What about the joys of a good chat?

SK: What is this talkativeness of yours Richard? It is the result of doing away with the vital distinction between talking and keeping silent. Only some one who knows how to remain essentially silent can really talk--and act essentially. Silence is the essence of inwardness, of the inner life. Mere gossip anticipates real talk, and to express what is still in thought weakens action by forestalling it. But some one who can really talk, because he knows how to remain silent, will not talk about a variety of things but about one thing only, and he will know when to talk and when to remain silent. Where mere scope is concerned, talkativeness wins the day, it jabbers on incessantly about everything and nothing...In a passionate age great events (for they correspond to each other) give people something to talk about. And when the event is over, and silence follows, there is still something to remember and to think about while one remains silent. But talkativeness is afraid of the silence which reveals its emptiness.

3:16: So death’s a big thing for you?

SK: Once you are born in this world you’re old enough to die. No one comes back from the dead, no one has entered the world without crying; no one is asked when he wishes to enter life, nor when he wishes to leave.

3:16: Whew! Heavy. Ok, you’re well known for having divided human existence into three stages – the aesthetic, the ethical and finally the religious. Let’s start by looking at the first stage – it’s basically the stage where we’re trying to break out of the boredom of life and make it bearably fun – being playful, ironical, willfully imaginative and so on isn’t it? I like this stuff, so what’s so bad about it?

SK: Oh my!!! I have just now come from a party where I was its life and soul; witticisms streamed from my lips, everyone laughed and admired me, but I went away — yes, the dash should be as long as the radius of the earth's orbit ——————————— and wanted to shoot myself. You recognize that Richard eh?

3:16: But passion is good isn’t it?

SK: It is impossible to exist without passion. Our own age is essentially one of understanding, and on the average, perhaps, more knowledgeable than any former generation, but it is without passion. Every one knows a great deal, we all know which way we ought to go and all the different ways we can go, but nobody is willing to move. Life, Richard, can only be understood going backward, but must be lived going forward.

3:16: So you want more action?

SK: A revolutionary age is an age of action; ours is the age of advertisement and publicity. Nothing ever happens but there is immediate publicity everywhere. In the present age a rebellion is, of all things, the most unthinkable. Such an expression of strength would seem ridiculous to the calculating intelligence of our times. On the other hand a political virtuoso might bring off a feat almost as remarkable. He might write a manifesto suggesting a general assembly at which people should decide upon a rebellion, and it would be so carefully worded that even the censor would let it pass. At the meeting itself he would be able to create the impression that his audience had rebelled, after which they would all go quietly home--having spent a very pleasant evening.

3:16: So this stage of life is ironical isn’t it?

SK: Irony is an abnormal development which, like the abnormality in the livers of Strasburg geese, ends by killing the individual.

3:16: I am sometimes ironical. Is that always bad?

SK: To be fair to you Richard, just as there is something deterring about irony, it likewise has something extraordinarily seductive and fascinating. It’s masquerading and mysteriousness, the telegraphic communication it prompts because an ironist always has to be understood at a distance. The ironist is the vampire who has sucked the blood of the lover and while so doing has fanned him cool, lulled him to sleep, and tormented him with troubled dreams. The ironic figure of speech has still another property that characterizes all irony, a certain superiority deriving from its not wanting to be understood immediately, even though it wants to be understood, with the result that this figure looks down, as it were, on plain and simple talk that everyone can promptly understand.

3:16: You connect irony with boredom don’t you – and seduction?

SK: Boredom is the only continuity the ironist has. Boredom is eternity devoid of content, is salvation devoid of joy, is superficial profundity, is hungry glut. But boredom is precisely the negative unity admitted into a personal consciousness, wherein the opposites vanish. Irony is the infinite absolute negativity. It is negativity, because it only negates; it is infinite, because it does not negate this or that phenomenon; it is absolute because that by virtue of which it negates is a higher something that still is not. Generally, we are used to seeing irony understood ideally, assigned its place as a vanishing moment of the system and therefore treated very briefly.

3:16: By system, you’re talking about Hegelianism here?

SK: Yes. For this reason we can not easily comprehend how a whole life can be taken up with it, since the content of this life must be regarded as nothing. But we do not remember that a standpoint is never as ideal in life than it is in the system. This is the purely personal life with which science is not involved, even though a somewhat more intimate acquaintance with it would free it from the tautological idem et idem, from which such understandings often suffer.

3:16: So Hegelian irony ignores the individual in its grand system?

SK: Whatever the case may be, grant science to be right in ignoring such things; nevertheless, one who wants to understand the individual life cannot do so.

3:16: Schelling is important to you isn’t he?

SK: When he mentioned the word ‘actuality’ concerning philosophy’s relation to the actual the child of thought leapt in me. This one word it reminded me of all my philosophical pains and agonies. I once put all my hope in Schelling.

3:16: But he didn’t deliver for you?

SK: What philosophers say about actuality is often just as disappointing as it is when one reads on a sign in a secondhand shop: Pressing Done Here. If a person were to bring his clothes to be pressed he would be duped; for the sign is merely for sale.

3:16: So the aesthetic stage of existence is criticized from the point of view of ethics as being self serving and escapist? It is selfish – has no recognition of any social responsibility?

SK: Let’s ask: What does it mean to live aesthetically, and what does it mean to live ethically? What is aesthetic in a person, and what is ethical? To that I would respond: the aesthetic in a person is that by which he spontaneously and immediately is what he is; the ethical is that by which he becomes what he becomes.

3:16: Why do you say that the aesthetic man is a seducer?

SK: His desire is for something altogether arbitrary. With the help of his mental gifts he knew how to tempt a girl to draw her to him without caring to possess her in any stricter sense. I can imagine him able to bring a girl to the point where he was sure she would sacrifice all then he would leave without a word let a lone a declaration a promise. The unhappy girl would retain the consciousness of it with double bitterness because there was not the slightest thing she could appeal to. She could only be constantly tossed about in a terrible witches' dance, at one moment reproaching herself, forgiving him at another reproaching him and then, since the relationship would only have been actual in a figurative sense, she would constantly have to contend with the doubt that the whole thing might only have been an imagination. He thinks whoever does not know how to encircle a girl so that she loses sight of everything he does not want her to see, he who does not know how to poetize himself into a girl so that it is from her that everything proceeds as he wants it- is and remains a bungler.

3:16: Hmm. Sounds a bit edgy.

SK: Oh pleeeese Richard. You cannot send for your traveling boots whenever you wish, you cannot move aimlessly about in the world. You like everyone else recognize all that - “I am poor—you are my riches; dark—you are my light; I own nothing, need nothing. And how could I own anything? After all, it is a contradiction that he can own something who does not own himself. I am happy as a child who is neither able to own anything nor allowed to. I own nothing, for I belong only to you; I am not, I have ceased to be, in order to be yours’ - shtick. Get real.

3:16: It’s kind of a Hegelian dialectical thing you do isn’t it by you preserving both the aesthetical and the ethical in the final stage, the religious. Is that why you use pseudonyms and humour throughout your work, to maintain this aestheticism?

SK: Well, the comical always consists in a contradiction.

3:16: You see Hegel as a bit hilarious don’t you?

SK: Well let’s be honest Richard: If Hegel had written the whole of his logic and then said, in the preface or some other place, that it was merely an experiment in thought in which he had even begged the question in many places, then he would certainly have been the greatest thinker who had ever lived. As it is, he is merely comic.

3:16: Fair enough.

SK: If a man seeks permission to establish himself as a proprietor of an alehouse and is refused, it is not comical. On the other hand, if a girl seeks permission to establish herself as a prostitute and is refused, which sometimes happens, then it is comical. The comic is always a sign of maturity. I consider the power in the comic a vitally necessary legitimation for anyone who is to be regarded as authorized in the world of spirit in our day. The more one suffers, the more sense, I believe, one gains for the comic. Only by the most profound suffering does one gain real competence in the comic, which with a word magically transforms the rational creature called man into a caricature.

3:16: So is the ethical better than the aesthetical because of its commitment to communication and decision procedures lacking in the aesthetic?

SK: The self that is the objective is not only a personal self but a social, a civic self. Personal life as such was an isolation and therefore imperfect, but when he turns back into his personality through the civic life, the personal appears in a higher form. Ethics points to ideality as a task and assumes that every man possesses the requisite conditions. Thus ethics develops a contradiction, inasmuch as it makes clear both the difficulty and the impossibility. The more ideal ethics is, the better. It must not permit itself to be distracted by the babble that it is useless to require the impossible. For even to listen to such talk is unethical and is something for which ethics has neither time nor opportunity. The ethical as such is the universal, and as the universal it applies to everyone, which from another angle means that it applies at all times.

3:16: What’s wrong with being shrewd?

SK: Long ago, when people were not so calculating, one sometimes saw a noble, a magnanimous act, genuine heroism. Now shrewdness stifles everything. If people do not manage to break free of this and learn to be quite scrupulous in scorning shrewdness – the contemptible peddler hawking earthly advantage – if they do not see that shrewdness, that behaving shrewdly corrupts oneself much more than stealing and murdering simply because everything here is intended to lull the conscience to sleep – if they do not succeed , everything is lost.

3:16: So for you the great threat to ethics is evading it, taking steps to avoid the questions its going to ask you?

SK: Yes. To desert one’s post, to flee in battle, is always dishonourable, but then sagacity has come up with an ingenious turn that obligingly forestalls flight – it is evasion. Therefore through evasion one never gets into danger and as a result does not lose one’s honour by fleeing in danger. And this is perhaps how the great majority of people live: they work gradually at eclipsing their ethical and ethical-religious comprehension, which would lead them out into decisions and conclusions that their lower nature does not much care for.

3:16: Ethical duties can’t be justified by social norms according to you can they? So how do you justify them?

SK: Well now, Kant was of the opinion that man is his own law – had autonomy – that is, he binds himself under the law which he himself gives himself. Actually , in a profounder sense, this is how lawlessness or experimentation are established. This is not being rigorously earnest any more than Sancho Panza’s self-administered blows to his backside were vigorous.

3:16: So ethics require we are serious, take our ethical actions as having truth values and are not just responses to feelings or whatever, that we’re choosing to do something rather than just responding, are rule bound and so on?

SK: All those yes. When a person has felt the intensity of the duty with all his energy, then he is ethically matured, and then duty will break forth within him. The fundamental point, therefore, is not whether a person can count on his fingers how many duties he has, but that he has once and for all felt the intensity of duty in such a way that the consciousness of it is for him the assurance of the eternal validity of his being. The ethical thesis that every human being has a calling expresses, then, that there is a rational order of things, in which every human being, if they so will it, fills his place in such a way that he simultaneously expresses the universally human and the individual.

3:16: But if ethics is cognitivist, for you the choosing of ethics is non-cognitivist in that it’s motivated largely by an attempt to avoid despair. Is that right?

SK: Doubt is thought’s despair; despair is personality’s doubt. Not to be in despair is not the same as not being lame, blind or whatever. If not being in despair signifies neither more nor less than not being in despair then it means precisely to be in despair. When death is the greatest danger we hope for life; but when we learn to know the even greater danger, we hope for death. When the danger is so great that death becomes the hope, then despair is the hopelessness of not even being able to die. To despair over oneself, in despair to will to be rid of oneself – this is the formula for all despair. And the specific character of despair is precisely this: it is unaware of being despair.

3:16: So ethics is a response to what? The anxiety and despair of existence? Is this how we must be motivated towards hearing ethical commands?

SK: Every human existence that is not conscious of itself as spirit or conscious of itself before God as spirit, every human existence that does not rest transparently in God but vaguely rests in and merges in some abstract universality – such as state, nation or whatever – or in the dark about his self, regards his capacities merely as powers to produce without becoming deeply aware of their source, regards his self, it is to have intrinsic meaning, as an indefinable something – every such existence, whatever it achieves, be it most amazing, whatever it explains, be it the whole of existence, however intensively it enjoys life aesthetically – every such existence is nevertheless despair.

3:16: So the question ethics raises is whether you’ve lived in despair or not?

SK: When the hourglass has run out, the hourglass of temporality, when the noise of secular life has grown silent and its restless or ineffectual activism has come to an end, when everything around you is still, as it is an eternity, then – whether you were man or woman, rich or poor, dependent or independent, fortunate or unfortunate, whether you ranked with royalty and wore a glittering crown or in humble obscurity bore the toil and heat of the day, whether your name will be remembered as long as the world stands and consequently as long as it stood or you are nameless and run nameless in the innumerable multitude, whether the magnificence encompassing you surpassed all human description or the most severe and ignominious human judgment befell you – eternity asks you and every individual in these millions and millions about only one thing: whether you have lived in despair or not.

3:16: To live in despair is bad yes?

SK: If you have lived in despair then, regardless of what else you won or lost, everything is lost for you, eternity does not acknowledge you, it never knew you – or still more terrible, it knows you as you are known and it binds you to yourself in despair. When it is impossible to possess the beloved in time, eternity says “You shall love” – that is, eternity then saves love from despair by making it eternal. Suppose it is death that separates the two – then what will be the help when the survivor would sin into despair? Temporal help is an even more lamentable kind of despair; but then eternity helps. When it says “You shall love” it is saying, “Your love has an eternal worth.”

3:16: It’s not easy to understand our despair is it?

SK: We can ask whether or not the person who his conscious of his despair has the true conception of what despair is. Admittedly, he can be quite correct, according to his own idea of despair, to say that he is in despair; he may be correct about being in despair, but that does not mean that he has the true conception of despair. And maybe what he calls despair is not despair but, in the meantime, sure enough, despair is right there behind him without his realising it. Most men are characterized by a dialectic of indifference and live a life so far from the good faith that it is almost too spiritless to be called sin – indeed almost too spiritless to be called despair. Despair itself is a negative; ignorance of it, a new negativity.

3:16: So the nadir of aesthetic existence is a despair where you lose your sense of self through cynicism and what you call somewhere the uncomprehending hysteria of the self-repressed spirit?

SK: That despair seems to permit itself to be tricked out of its self by ‘the others.’ Surrounded by hordes of men, absorbed in all sorts of secular matters, more and more shrewd about the ways of the world – such a person forgets himself, forgets even his own name divinely understood, does not dare to believe in himself, finds it easier and safer to be like others, to become a copy, a number, a mass man. Of that hysteria there comes a moment in a person’s life when immediacy is ripe, so to speak, and the spirit requires a higher form, when it wants to lay hold of itself as spirit. This hysteria of spirit is a kind of depression, it is the sin of not willing deeply and inwardly, and this is the mother of all sins. Now this form of despair goes practically unnoticed in the world. Precisely by losing oneself in this way, such a person gains all that is required for a flawless performance in everyday life, yes, for making a great success out of life. Here there is no dragging of the feet, no difficulty with his self and its infinitizing, he is ground smooth as a pebble, as exchangeable as a coin of the realm. Far from anyone thinking him to be in despair, he is just what a human being ought to be. Naturally, the world has generally no understanding of what is truly horrifying.

3:16: This is a bit of a downer. I mean, things are tricky for lots of us these days –what with Covid and war and global warming - don’t you think you could be a bit more upbeat?

SK: There speaks the immediacy man!!! Look, deepest within every person there is an anxiety about being alone in the world, forgotten by God, overlooked among the millions and millions in this enormous household. People keep this anxiety at bay by looking at the many people around them, who are related to them as family and friends; but the anxiety is there all the same – one scarcely dare think how one would feel if all these were taken away. To suppose that anxiety is an imperfection merely betrays a straightlaced cowardice since, to the contrary, the greatness of anxiety is the very prophet of the miracle of perfection, and inability to become anxious is a sign of one’s being either an animal or an angel, which is less perfect than being a human being.

3:16: So awareness of anxiety can be a good sign?

SK: Anxiety is the first reflex of possibility, a glimpse, and yet a terrible sorcery. It’s the vehicle by which the subject appropriates sorrow and assimilates it. Anxiety is the motive power by which sorrow penetrates a person’s heart. But the movement is not swift like that of an arrow; it is consecutive; it is not once and for all, but is continually being. As a passionately erotic glance craves its object, so anxiety looks cravingly upon sorrow. And about our days. Well, enough has been said about the light-mindedness of the age, it is high time, I think Richard, to say a little about its depression, and I hope everything will turn out better. Or is not depression the defect of the age, is it not that which echoes even in its light minded laughter; is it not depression that has robbed us of the courage to command, the courage to obey, the power to act, the confidence to hope?

3:16: I take it that you are depressed then?

SK: Richard, depression is my nature, that is true, but thanks be to the power who, even if it bound me in this way, nevertheless also gave me consolation. There are animals that are only poorly armed against their enemies, but nature has provided them with a cunning by which they are nevertheless are saved. I too was given a cunning such as this, a capacity for cunning that makes me just as strong as everyone against whom I have tested my strength. My cunning is that I am able to hide my depression; my deception is just as cunning as my depression is deep.

3:16: But you are depressed?

SK: I have one intimate confident – my depression. In the midst of my joy, in the midst of my work, she beckons to me, calls me aside, even though physically I remain on the spot. My depression is the most faithful mistress I have known – no wonder that I return the love. I have only one friend and that is echo. Why is it my friend? Because I love my sorrow, and echo does not take it away from me. I have only one confidant, and that is the silence of the night.

3:16: So depression isn’t always bad?

SK: There is something unexplainable in depression. A person with a sorrow or a worry knows why he sorrows or worries. If a depressed person is asked what the reason, what it is that weighs on him, he will answer I do not know, I cannot explain it. Therein lies the limitlessness of depression.

3:16: I’m not sure if you’re saying it’s good or bad?

SK: Well it is a cowardly craving of depression to want to become dizzy in the emptiness and seek the final diversion to this dizziness. Depression is sin, is actually a sin that stands for all, for it is the sin of not willing deeply or inwardly. The soul of the melancholic spends a great deal of time at the eye, seeking diversions. Another form is that which completely closes its eye in order to darken everything around itself. Depression is something real that one does not delete with the stroke of a pen. Here’s another common thing in depression: precisely because she is depressed she has an abstract notion that life for others is so pleasant and happy. But what the unfamiliar is like one cannot know in the abstract. Here is fraudulence that is inseparable from all depression.

3:16: And the same about about anxiety?

SK: It is the next day. It’s freedom’s possibility. It consumes all finite ends and discovers all their deceptiveness.

3:16: The next day? What do you mean ‘anxiety is the next day’? That’s blowing my mind man.

SK: ‘Let us eat and drink because tomorrow we shall die.’ This very remark echoes with the anxiety about the next day, the day of annihilation, the anxiety that insanely is supposed to signify joy though it is a shriek from the abyss.

3:16: A shriek? That’s dark Soren.

SK: A shriek because he is so anxious about the next day, Richard, that he plunges himself into a frantic stupor in order, if possible, to forget it – and how anxious he is – is this what it means to be without care about the next day Richard? I don’t think so, no.

3:16: Bejeezus.

SK: The ethical expression for what Abraham did is that he meant to murder Isaac; the religious expression is that he meant to sacrifice Isaac – but precisely in this contradiction is the anxiety that can make a person sleepless, and yet without this anxiety Abraham is not who he is. There is not one single human being who does not despair a little.

3:16: So we can glimpse what you think a person is from all this?

SK: Man is a synthesis of the psychical and the physical in immediacy but needs spirit to endure. Unaware of being defined by spirit all immediacy is anxiety. To choose spirit is to choose in ethical terms: in this it matters not so much to choose the right thing as the energy, the earnestness, and the pathos with which one chooses.

3:16: Is this groundless choice actually grounded in existential anxiety?

SK: The formula that describes the state of the self when despair is completely rooted out is this: in relating itself to itself, and in willing to be itself, the self rests transparently in the power that established it.

3:16: So self consciousness is critical here?

SK: My oh my yes. Self consciousness is decisive for the self. The more consciousness , the more self; the more consciousness, the more will; the more will, the more self. A person who has no will at all is not a self, but the more will he has, the more self-consciousness he has also.

3:16: So faith is a leap into the dark?

SK: Leap of faith – yes, but only after reflection

3:16: But isn’t the aesthetic man self conscious?

SK: Sadly no. The man of immediacy is only psychically qualified. His self is bound up in immediacy with the other object in desiring, craving, enjoying and so on.

3:16: So after the aesthetic and the ethical stages it is through religion that you express the final stage of human existence. Of course, you’re someone steeped in Christian Lutheran pietism which is full of sin, guilt, suffering and individual responsibility – so it’s a very specific religion with a definite flavour that might strike many as being not very appealing. So perhaps you could say something about what you take Christianity to be saying?

SK: Ok. Big topic. So here are a few things. The consciousness of sin is and remains conditio sine qua non for all Christianity. Also: there is so much talk about how Christianity presupposes nothing at all on the part of the human being but it obviously presupposes one thing: that is, self love, for Christ obviously presupposes it when he says that love of the neighbour is to be as great as love toward ourself. What Socrates says about loving the ugly is really the Christian teaching concerning love of neighbour. And one must really have suffered very much in the world, have become very unhappy, before there can be any talk of beginning to love one’s neighbour. Only in self-denial’s dying-away from earthly delight and happiness and happy days, only then does “the neighbour” come into existence. Everyone who clings to earthly life does not love his neighbour, that is, his neighbour does not exist for him.

3:16: Christianity has a big historical role for you doesn’t it?

SK: Christianity is the only historical phenomenon that despite the historical – indeed precisely by means of the historical – has wanted to be the single individual’s point of departure for his eternal consciousness, has wanted to interest him otherwise than merely historically, has wanted to base his happiness on his relation to something historical. In those early days a Christian was a fool in the eyes of the world. To the pagans and Jews it was foolishness for him to want to become one.

3:16: So you think the incarnation is the key transition point in history – is this why you think Hegel’s system fails because he ignored it ?

SK: Negation, transition, mediation are three disguised , suspicious and secret agents that bring about all movements. Hegel would hardly call them presumptuous because it is with his gracious permission that they carry on their ploy so unembarrassedly that even logic uses terms and phrases borrowed from the temporality of transition. Let this be as it may. Let logic take care to help itself. The term transition is and remain a clever turn in logic. Transition belongs in the sphere of historical freedom, for transition is a state and is actual. Plato fully recognised the difficulty of placing transition in the realm of the purely metaphysical, and for that reason the category <em>the instant</em>cost him so much.

3:16: And you find that ‘instant’ in Christianity?

SK: The pivotal concept in Christianity, that which made all things new, is the fullness of time, but the fullness of time is the instant as the eternal, and yet this eternal is also the future and the past.

3:16: So Hegel doesn’t regard God’s act of incarnation as a hinge moment, even though Hegel’s system is ostensibly a Christian one?

SK: If attention is not paid to this, not a single concept can be saved from a heretical and treasonable admixture that annihilates the concept. One does not get the past by itself but in a simple continuity with the future - with this the concepts of conversion, atonement, and redemption are lost in the world-historical significance are lost in the individual historical development. The future is not by itself but in a simple continuity with the present – thereby the concepts of resurrection and judgment are destroyed.

3:16: So is this religious event an ontological demand to be the self in the spirit we’ve been talking about? Is this why you think Hegel has no room for an ethics in his system?

SK: Yes, the system lacks an ethics; therefore the system knows nothing when the living generation and the living individual ask in earnest about becoming in order, namely, to act.

3:16: And you’d agree with Fichte that to understand our relationship with this incarnation we need to be serious about the individual/God connection?

SK: To help a person relate themselves to God is seriousness yes. But it must be done indirectly, for otherwise it becomes a hindrance to the one being helped. Most people think it is seriousness to get an official position, to be attentive to the fact that a higher position, which one can seek, will soon be vacancy, and how they can make the move, and what they will then do in order to arrange things. They think it is seriousness to attend distinguished social gatherings; they prepare themselves for a dinner party with his Excellency more than for Holy Communion, and when you see them on their way there, they look so serious that it is quite awful. Look, I can understand this very well. The only think I cannot understand is that if this is truly serious then eternity must be sheer fun and games for in eternity there is neither preferment nor promotion nor is there a moving day or dinner parties at the homes of Excellencies.

3:16: So Christianity involves dogmas which embody paradoxes which offend reason? The big one is that eternal God became particular incarnate man! This is an important feature of the religion isn’t it?

SK: Yes – the eternal truth has come into existence in time. That is the paradox. The paradox is the authentic pathos of the intellectual life, and just as only great souls are susceptible to passions, so are only great thinkers susceptible to what are called paradoxes, which are nothing other than grandiose thoughts not yet fully developed. The ultimate potentiation of every passion is always to will its own downfall, and so it is also the ultimate passion of the understanding to will the collision, although in one way or another the collision must become its downfall. This, then, is the ultimate paradox of thought: to want to discover something that thought itself cannot think.

3:16: And is faith also a paradox then?

SK: Quite so. How else could it have as its object in the paradox and be happy in its relation to it? Faith itself is a wonder, and everything that is true of the paradox is also true of faith. The paradox of faith is this: that the single individual is higher than the universal, that the single individual determines his relation to the universal by his relation to the absolute, not his relation to the absolute by his relation to the universal.

3:16: You’re pretty harsh when you talk about actual Christians as opposed to Christianity aren’t you? What’s the problem?

SK: Our generation does not stop with faith, does not stop with the miracle of faith, turning water into wine – it goes further and turns wine into water. The knights of infinite resignation are easily recognizable – their walk is light and bold. But they who carry the treasure of faith are likely to disappoint, for externally they have a striking resemblance to bourgeois philistinism, which infinite resignation, like faith, deeply disdains. I just wonder if anyone in my generation can make the movements of faith.

3:16: is it because the religion is hard to understand?

SK: Are you kidding me? The Bible is very easy to understand. But we Christians are a bunch of scheming swindlers. We pretend to be unable to understand it because we know very well that the minute we understand, we are obliged to act accordingly. Take any words in the New Testament and forget everything except pledging yourself to act accordingly. My God, you will say, if I do that my whole life will be ruined. How would I ever get on in the world? Herein lies the real place of Christian scholarship.

3:16: So you don’t think much of Christian theology or philosophy or religion?

SK: Christian scholarship is the Church’s prodigious invention to defend itself against the Bible, to ensure that we can continue to be good Christians without the Bible coming too close. Oh, priceless scholarship, what would we do without you? Dreadful it is to fall into the hands of the living God. Yes it is even dreadful to be alone with the New Testament. There is something frightful in the fact that the most dangerous thing of all, playing at Christianity, is never included in the list of heresies and schisms. The greatest danger to Christianity is, I contend, not heresies, heterodoxies, not atheists, not profane secularism – no, but the kind of orthodoxy which is cordial drivel, mediocrity served up sweet.

3:16: So your understanding of real Christianity is that it’s a kind of absurdist drama?

SK: What is the absurd? The absurd is that the eternal truth has come into existence in time, that God has come into existence, has been born, has grown up and so on, has come into existence exactly as an individual human being, indistinguishable from any other human being. The absurd, the paradox, is composed in such a way that reason has no power at all to dissolve it in nonsense and prove it is nonsense; no, it is a symbol, a riddle, a compounded riddle about which reason must say: I cannot solve it, it cannot be understood, but it does not follow thereby that it is nonsense.

3:16: Very Wittgenstein!

SK: The concept of the absurd ought to be developed for it is nothing but superficiality to think that the absurd is not a concept, that all sorts of absurdities belong equally under the absurd. The concept of the absurd is precisely to grasp the fact that it cannot and must not be grasped.

3:16: Don’t you think that some of the stories and dogmas of religion can be a bit hard to take – more theatre of cruelty than of the absurd?

SK: Yes. Although Abraham arouses my admiration he also appalls me. Abraham was the greatest of all, great by that power whose strength is powerlessness, great by that wisdom which is foolishness, great by that hope whose form is madness, great by the love that is hatred to oneself.

3:16: Well, I have to raise the issue – some of us rather think there isn’t a God. Does this worry you?

SK: Well God can just as little prove his existence in any other sense than that in which he is able to swear: he has nothing higher to swear by than himself. Precisely because God cannot be an object for human beings, because God is subject, precisely for this reason the reversal shows itself absolutely: when one denies God – then he does no injury to God, but annihilates himself; when one mocks God – then he mocks himself. When a person has withdrawn from the world in an external sense but does not live in communion with God, that is, he has the world with him in his thoughts – this person is not solitary; he lives alone but is not solitary. For the fool says in his heart that there is no God, but he who says in his heart or to others: Just wait a little and I shall demonstrate it – ah, what a rare wise man he is!

3:16: So what is this God like?

SK: Since everything is possible for God, then God is this – that everything is possible.

3:16: So he’s not a version of the Hegelian moving-spirit-in-an-immanent world-historical-process-thingy?

SK: It’s hardly playing the role of the Lord to be laced in a half-metaphysical, half-aesthetic-dramatic-conventional corset. That’s a devil of a way to be God - and besides divine freedom will never in all eternity become immanence.

3:16: You see when I hear that kind of thing it makes me wonder – and I’m not alone in this Soren – it makes me wonder whether you think God actually exists. After all you say that all language about God is human language and all human language about the spiritual is essentially metaphorical don’t you?

SK: I do Richard. All human speech, even divine speech of Holy Scripture, about the spiritual is essentially metaphorical speech. Language has time as its element; all other media have space as their element. And the misfortune of our time is just this, that it has become simply nothing else but 'time', the temporal, which is impatient of hearing anything about eternity.

3:16: Yes, good,– but if he’s eternal and all that then how can mere human language and thought find a right comparison to understand God? Isn’t the great theological absurdity the impossibility of the word God? If God no more than a metaphor then what’s God a metaphor for – well there’s the rub?

SK: Richard you do not reach the possibility of comparison by the ladder of direct likeness: great, greater, greatest; it is possible only inversely. Neither does a human being come close and closer to God by lifting his head higher and higher but inversely by casting himself down ever more deeply in worship. In worship we do indeed know God in a different way, more intimately, if one may say so, than out there in nature, where he is surely manifest, is known in his works, whereas here he is known as he has revealed himself as he wants to be known by the Christian.

3:16: Which is how?

SK: Via human sin, the one and only predication about a human being that in no way, either by denial or by affirmation can be stated of God. There is one way in which the human being could never in all eternity come to be like God: in forgiving sins. But Richard, when a Christian says God is a loving Father from whom comes every good and perfect gift to the Christian it is not metaphorical, imperfect, but the truest and most literal expression, because God gives not only gifts but himself with them in a way beyond the capacity of any human being. Everything that a human being knows about the eternal is contained primarily in this: it is God who rules, because whatever more a person comes to know pertains to how God has ruled or rules or will rule.

3:16: So you laugh at the Hegelians and the other speculative theologians because they don’t do this, they aren’t content to ‘let God rule’ as you put it?

SK: You got it! Our earthly life, which is frail and inform, must separate explaining and being, and this weakness of ours is an essential expression of how we relate to God. God is not something external, as is a wife, whom I can ask whether she is now satisfied with me. The voice of God is always a whisper. Only when someone becomes nothing, only then can God illuminate him so that he resembles God. However real he is, he cannot manifest God’s likeness; God can imprint himself in him only when he himself has become nothing. . When the ocean is exerting all its power, that is precisely the time when it cannot reflect the image of heaven, and even the slightest motion blurs the image; but when it becomes still and deep, then the image of heaven sinks into its nothingness.

3:16: What about science? Isn’t it a bit worrying that the natural sciences find no traces of a God or anything like the things you discuss? There are some of these scientists who find religious beliefs offensive and perpetrated by charlatans and liars. They can get pretty bad tempered.

SK: Yes, well, it might well seem that there is a difficulty, inasmuch as natural science, the eagerness to understand, has made votaries and adherents enthusiastic, and thus to this extent understanding and enthusiasm do not appear to conflict with one another. It must however be noted that a natural scientist who is really and truly enthusiastic in grasping and understanding things does not notice that he himself is continually positing that which he wants to abrogate. He is enthusiastic about understanding everything else, but he does not come to understand that he himself is enthusiastic – that is, he does not come to conceptualise his own enthusiasm even though, in this enthusiasm, he is enthusiastic about conceptualizing everything else.

3:16: Many are skeptical about ethics being more than human invention.

SK: In our times, it is especially the natural sciences that are dangerous. Physiology will ultimately expand so much that it will annex ethics. Indeed there are already signs of a new attempt to treat ethics as physics, whereby the whole of ethics becomes an illusion, and the ethical aspect of the human race will be treated statistically. Absolutely no benefit can be derived from involving oneself with the natural sciences. One stands there defenceless, with no control over anything. The researcher immediately begins to distract one with his details: Now one is to go to Australia; now to the moon; now into an underground cave; now up the ass – to look for an intestine worm; now the telescope must be used; now the microscope; Who the devil can endure it!

3:16: What about recent work on the science of the self?

SK: No science can say what the self is without again stating it quite generally. We’re a synthesis of psyche and body but also a synthesis of the temporal and the eternal. Every human life is religiously designed. A human being is spirit.

3:16: So what’s spirit?

SK: Spirit is the self. But what is the self? The self is a relation that relates itself to itself or is the relations’ relating itself to itself in relation; the self is not the relation but is the relation’s relating to itself.

3:16: Wow, so you’re turning Fichte’s idea of a radically autonomous self-generation on its head and agreeing with Schelling that the self is posited by God?

SK: You betcha! A person cannot rid himself of the relation to himself any more than he can rid himself of his self, which, after all, is one and the same thing, since the self is relation to oneself.

3:16: Ok, so how does this happen?

SK: Development of spirit is self-activity; the spiritually developed individual takes his spiritual development along with him in death. If a succeeding individual is to attain it, it must occur through his self-activity, therefore, he must skip nothing. To have been young, then to have grown older, and then finally to die is a mediocre existence, for the animal also has that merit. But to unite the elements of life in contemporaneity, that is precisely the task. When all is said and done, whatever of feeling, knowing and willing a person has depends upon what imagination he has, upon how that person reflects himself – that is, upon imagination.

3:16: This self seems both important and fragile especially these days when everyone seems so distracted?

SK: Well, Richard, a self is the last thing the world cares about and the most dangerous thing of all for a person to show a sign of having. The greatest hazard of all, losing the self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all. No other loss can occur so quietly; any other loss – an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife etc – is sure to be noticed.

3:16: So you want people to wake up to the fact that they have this ability to be a self and not be frightened by its potential?

SK: There is nothing of which every man is so afraid as getting to know how enormously much he is capable of. No one is born devoid of spirit, and no matter how many go to their death with this spiritlessness as the one and only outcome of their lives, it is not the fault of life.

3:16: So you think everyone can and should be more than living from day to day with no sense of meaning and purpose?

SK: Every human being, no matter how slightly gifted he is, however subordinate his position in life may be, has a natural need to formulate a life-view, a conception of the meaning of life and of its purpose. The truth of the matter is this. All of us human beings are more or less intoxicated. But we are like a drunk man who is not completely drunk so that he has lost his consciousness – no, he is definitely conscious that he is a little drunk and for that very reason is careful to conceal it from others, if possible from himself.

3:16: I recognize that!

SK: But what then does he do? He looks for something to sustain himself; he walks close to the buildings and walks erect without becoming dizzy – a sober man.

3:16: So our constantly trying to be respectable and fit in with the herd is like that?

SK: Imagine a house with a basement, first floor and second floor planned so that there is or is supposed to be a social distinction between the occupants according to floor. Now, if what it means to be a human being is compared with such a house, then all too regrettably the sad and ludicrous truth about the majority of people is that in their own house they prefer to live in the basement.

3:16: So we’re back to this familiar guy you call the man of immediacy?

SK: Oh yes. Your man of immediacy, Richard, doesn’t know himself, he quite literally identifies himself only by the clothes he wears, he identifies having a self by externalities (here again the infinitely comic). There is hardly a more ludicrous mistake, for a self is indeed infinitely distinct from an externality.

3:16: Wow. But it’s difficult to be more than that isn’t it? It seems risky to try for more. Isn’t it simpler to just let vanity and conceit get us through the tribulations of life?

SK: However vain and conceited men may be they usually have a very meagre conception of themselves nevertheless, that is, they have no conception of being spirit, the absolute that a human can be; but vain and conceited they are – on the basis of comparison. Actually, it is exceedingly comic that a speaker with sincere voice and gestures, deeply stirred and deeply stirring, can movingly depict the truth, can face all the powers of evil and hell boldly, with cool self-assurance in his bearing, a dauntlessness in his air, and an appropriateness of movement worthy of admiration – it is exceedingly comic that almost simultaneously, practically still in his dressing gown he can timidly and cravenly cut and run away from the slightest inconvenience. But you’re right Richard, there are very few persons who live even approximately within the qualification of spirit; indeed, there are not many who even try this life, and most of those who do soon back out of it. They have not learned to fear, have not learned “to have to” without any dependence, none at all, upon whatever else happens.

3:16: So how do we become aware of our selves?

SK: Imagination must raise him higher than the miasma of probability, it must tear him out of this and teach him to hope and to fear – or to fear and to hope – by rendering possible that which surpasses the sufficient standard of any experience.

3:16: That’s where the ethical choice comes in isn’t it? It’s difficult isn’t it?

SK: In every person there is something that up to a point hinders him from becoming completely transparent to himself, and this can be the case to such a high degree, he can be so inexplicably intertwined in the life – relations that lie beyond him, that he cannot open himself.

3:16: I get that feeling a lot to be honest Soren.

SK: Ah Richard, this is what is sad when one contemplates human life, that so many live out their lives in quiet lostness; they outlive themselves, not in the sense that life’s content successively unfolds and is now possessed in this unfolding, but they live, as it were, away from themselves and vanish like shadows. Their immortal souls are blown away, and they are not disquieted by the question of its immortality, because they are already disintegrated before they die.

3:16: Some think you’re a bit too individualistic and don’t have a political philosophy? At the moment there’s a lot of talk about freedom of speech – do you have a position on this?

SK: How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech. People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought which they seldom use. There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn't true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true.

3:16: Our times are troubled though don’t you think?

SK: Let others complain that the age is wicked; my complaint is that it is paltry; for it lacks passion. Men's thoughts are thin and flimsy like lace, they are themselves pitiable like the lacemakers. The thoughts of their hearts are too paltry to be sinful. For a worm it might be regarded as a sin to harbor such thoughts, but not for a being made in the image of God. Their lusts are dull and sluggish, their passions sleepy...This is the reason my soul always turns back to the Old Testament and to Shakespeare. I feel that those who speak there are at least human beings: they hate, they love, they murder their enemies, and curse their descendants throughout all generations, they sin.

3:16: There seems to be a sectarian spirit abroad. It’s getting ugly.

SK: The true knight of faith is always absolute isolation, the false knight is sectarian. This sectarianism is an attempt to leap away from the narrow path of the paradox and become a tragic hero at a cheap price. The tragic hero expresses the universal and sacrifices himself for it. The sectarian punchinello, instead of that, has a private theatre, i.e. several good friends and comrades who represent the universal just about as well as the beadles in The Golden Snuffbox represent justice. The knight of faith, on the contrary, is the paradox, is the individual, absolutely nothing but the individual, without connections or pretensions. This is the terrible thing which the sectarian manikin cannot endure. For instead of learning from this terror that he is not capable of performing the great deed and then plainly admitting it (an act which I cannot but approve, because it is what I do) the manikin thinks that by uniting with several other manikins he will be able to do it. But that is quite out of the question. In the world of spirit no swindling is tolerated.

3:16: Does your investigation into the tragic correspond to your thinking about irony?

SK: The rebirth of ancient tragedy is the attempt to show how the characteristic feature of the tragic in ancient drama can be incorporated in the tragic of modern drama in such a way that what is truly tragic will become apparent. Ancient tragedy has the hereditary guilt of sorrow. Modern tragedy has pain. The modern Antigone has both.

3:16: You love poetry don’t you? You count yourself as one don’t you?

SK: A poet is not an apostle; he drives out devils only by the power of the devil. What is a poet? A poet is an unhappy being whose heart is torn by secret sufferings, but whose lips are so strangely formed that when the sighs and the cries escape them, they sound like beautiful music… and men crowd about the poet and say to him: “Sing for us soon again”; that is as much to say: May new sufferings torment your soul. If we ask what poetry is we may say in general that it is a victory over the world; it is through a negation of the imperfect actuality that poetry opens up a higher actuality.

3:16: Have you a take-home thought for us?

SK: Well Richard, the task is not to find the lovable object, but to find the object before you lovable – whether given or chosen – and to be able to continue finding this one lovable, no matter how that person changes. To love is to love the person one sees. Love is the expression of the one who loves, not of the one who is loved. Those who think they can love only the people they prefer do not love at all. Love discovers truths about individuals that others cannot see.To cheat oneself out of love is the most terrible deception; it is an eternal loss for which there is no reparation, either in time or in eternity.

3:16: And are there 5 books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

SK: Sure.

Holderlin: Poetry

Fichte: The Vocation of Man

Schelling: Essays

Luther's Bible

Hegel: Science of Logic

About the Author

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.