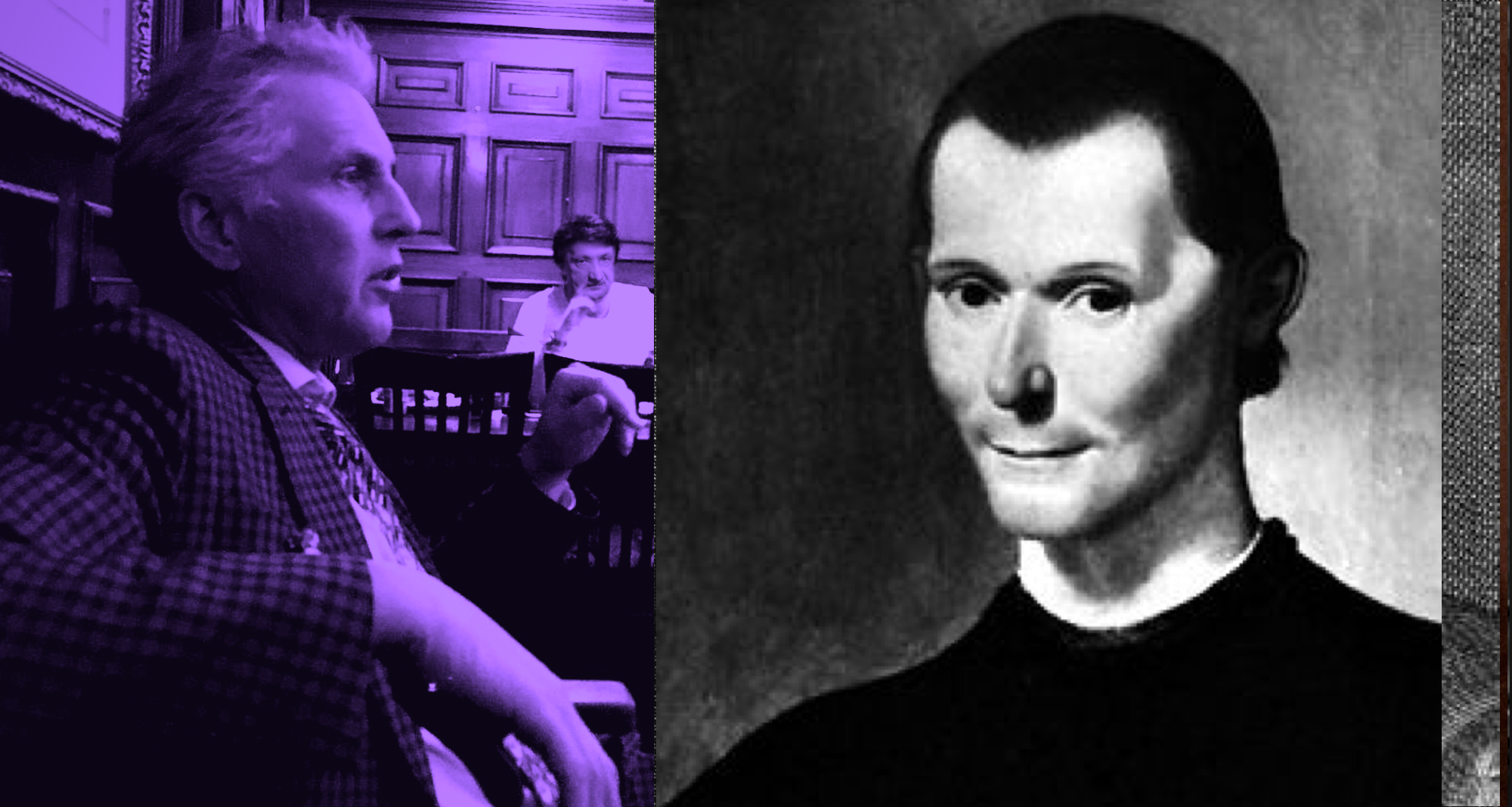

Exclusive 3:16 Interview With Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli is an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian best known for his political treatise The Prince (Il Principe). He has often been called the father of modern political philosophy and political science. For many years he served as a senior official in the Florentine Republic with responsibilities in diplomatic and military affairs. He writes comedies, carnival songs, and poetry. His personal correspondence is also important. He currently works as secretary to the Second Chancery of the Republic of Florence.

3:16: Thanks for agreeing to the interview by the way. I believe it's been quite a morning for you and I guess the issue helps remind us what kind of life and world you find yourself in.

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli: Well, Richard, this morning Messer Remirro was found in two pieces on the public square, where he still is: the whole city has been to see him: nobody is sure of the reason for his death except that it was the will of the prince who shows himself capable of making men and breaking them as he pleases, according to their merits.

3:16: I recall what Laski says of you, that the whole of the Renaissance is in you, its lust for power; its admiration for success, its carelessness of means, its rejection of medieval bonds, its frank paganism, its conviction that national unity makes for national strength and that neither your cynicism nor your praise of craftiness is sufficient to conceal the idealist in you. Is this desire to get to grips with the Renaissance and the modern world what made you become a philosopher?

NM: I don't think I am a philosopher really Richard. I have found that nothing in my belongings that I care so much for and esteem so greatly as the knowledge of the actions of great men, learned from long experience with modern things and a continuous reading of ancient ones. When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass indeed into their world. Everyone who wants to know what will happen ought to examine what has happened: everything in this world in any epoch has their replicas in antiquity.

3:16: Your approach is considered quite new by some. Do you think you’re doing something new with political philosophy?

NM: I'm not interested in preserving the status quo; I want to overthrow it and it must be considered that there is nothing more difficult to carry out, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to handle, than to initiate a new order of things. There are three classes of intellects: one which comprehends by itself; another which appreciates what others comprehend; and a third which neither comprehends by itself nor by the showing of others; the first is the most excellent, the second is good, the third is useless.

It ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. This coolness arises partly from fear of the opponents, and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them.

3:16: Wow. Ok, so let's begin by talking about political legitimisation. Many feel that good law is the basis of political legitimization. Do you agree?

NM: No. Since there cannot be good laws without good arms, I will not consider laws but speak of arms.

3:16: So power is all that we need to legitimize sovereignty?

NM: Didn’t I just say that?

3:16: Ok. Now, you basically consider two contrasting forms of government – principalities and Republics . Let’s start with your theories about the Prince and his rule. What is a principality in your theory, and how does a ruler get to be a ruler?

NM: Right. All states, all powers that rule over men, are either republics or principalities. I am saying all this about the past as well as the present. Principalities are either hereditary, governed by one family over very many years, or they are new. I say at the outset that it is easier to hold a hereditary state that has long been accustomed to their princely family than it is to hold a new state. A hereditary prince doesn’t have to work very hard to retain his state; all he needs is to abide by the customs of his ancestors and get himself through minor emergencies; unless of course some extraordinary and extreme force deprives him of his state, and even then he will get it back if the usurper runs into trouble.

3:16: So new states are where troubles arise?

NM: Yes. Distinguish two cases: when a state with a long history acquires a new dominion, either the new dominion has the same language as the other and is geographically right next to it, or it doesn’t and isn’t. In any case of the first kind it is easier to hold onto the new dominion, especially if its people haven’t been accustomed to live in freedom; to hold it securely one needs only to destroy the family of the prince who was its ruler; because then, with conditions ·in the new dominion· the same as before, and with pretty much the same customs established in the two territories, the people will live quietly together.

We have seen this in Brittany, Burgundy, Gascony, and Normandy, which have stayed united to France for such a long time. But when the second kind comes about a country acquires a state that differs from it in language, customs, or laws, there are difficulties, and holding on to the new acquisition requires good fortuna and great energy. One of the best things that the acquiring ruler can do is to go and live in the newly acquired state, which would make his position more secure and durable. That’s what it did for the Turk in Greece: despite all his other measures for holding that state, if he hadn’t settled there he couldn’t have kept it. An even better procedure is to send colonies to one or two places within the newly acquired state, to serve as shackles (so to speak). It’s a choice between doing this and keeping there a large garrison of cavalry and infantry.

Establishing and maintaining a colony costs little or nothing; and the only people who are offended by are the minority whose lands and houses are given to the new inhabitants, the colonists; and they can’t do the prince any harm, because they are poor and scattered.

3:16: So what you’re pointing to is the logic of the various situations rulers face. You’re basically working out the does and don’ts of given situations. Are you finding any general rules?

NM: Yes. For example this a general rule which never —or hardly ever —fails, namely: someone who causes someone else to become powerful brings about his own ruin; because it takes skill or power to do that, and these attributes will be seen as threatening by the one who has benefited from them. During a conversation about these matters that I had in Nantes with the Cardinal of Rouen, he remarked that the Italians don’t understand war, and I replied that the French don’t understand politics, because if they did they wouldn’t have allowed the Church to become so powerful. And so it turned out: France caused the Church and Spain to be great powers in Italy, which then led to France’s downfall.

3:16: You contrast the rule of the Turks with that of the French. What are the differences and what difference do they make?

NM: All the principalities of which we have any record have been governed in one of two ways: by a prince with the help of others whom he appoints to serve as his ministers in governing the kingdom, ·and whom he can dismiss at will·; or by a prince together with his barons whose rank isn’t given to them by him but is possessed by hereditary right. These two forms of government are illustrated in our own day by the Turk and the King of France. If you think about the difference between these two States, you’ll see that it would be hard to conquer that of the Turk but that once conquered it would be easy to hold onto. If an attacker overcomes the prince of a country governed as Turkey is, defeating him in battle so that his armies are beyond repair, he has nothing more to worry about—except for the prince’s family, and once that is exterminated there is no-one else to fear.

The opposite is the case in kingdoms governed in the French way. You can always make inroads into such a kingdom with the help of a baron or two, because there are always some who are disaffected and want change. But the effort to hold onto this territory will involve you in endless difficulties—problems concerning those who helped you and those whom you have overthrown. It won’t be enough merely to destroy the prince’s family, because there will be barons who are ready to lead new revolts; you’ll never be able to satisfy them or destroy them, so you’ll lose the state as soon as they see a chance to take it from you.

3:16: Have you evidence for this?

NM: If you look at the kind of government that Darius had, you’ll see that it resembled that of the Turk; so that Alexander had first to defeat him utterly and take control of his territory ·with no inside help·; but after he had done that, and Darius had died, Alexander was securely in control of the country, for the reasons I have given. If you bear all this in mind, you won’t be surprised by how easily Alexander got a firm grip on Asia, or by how hard it was for many others—Pyrrhus, for example—to retain the territories they had conquered. This came not from these conquerors’ differing in virtù but from a difference in the characters of the states they had conquered.

3:16: We’ll come to this virtù in a bit, but let’s stick with looking at the different options facing rulers based on the logic of the situation. What options face conquerors when a conqueror acquires a state that has been accustomed to living under its own laws and in freedom?

NM: He can destroy it, smash everything·, go and live there himself, or let them continue with their present system of laws, while paying taxes to him, and setting up there a small governing group who will keep the state friendly to you.

3:16: Sowhat do you mean when you say that the ruler must have the qualities of virtù?

NM: They’re qualities needed to maintain his state and achieve great things. He must have a flexible disposition to rule as fortune and circumstances dictate. He must be prepared to vary his conduct as the winds of fortune and changing circumstances constrain him and not deviate from right conduct if possible, but be capable of entering upon the path of wrongdoing when this becomes necessary. If it were possible to change one's nature to suit the times and circumstances, one would always be successful.

3:16: Where does this quality come from?

NM: People nearly always walk in paths beaten by others, acting in imitation of their deeds, but its never possible for them to keep entirely to the beaten path or achieve the level of virtù of the models you are imitating. A wise man will follow in the footsteps of great men, imitating ones who have been supreme; so that if his virtù doesn’t reach the level of theirs it will at least have a touch of it.

3:16: Are there princes who rule by their own virtù and don't rely on fortuna at all?

NM: Yes. In these we don’t find them owing anything to fortuna beyond ·their initial· opportunity, which brought them the material to shape as they wanted. Without that opportunity their virtù of mind would have come to nothing, and without that virtù the opportunity wouldn’t have led to anything. Men like these who become princes through the exercise of their own virtù find it hard to achieve that status but easy to keep it. One of the sources of difficulty in acquiring the status of prince is their having to introduce new rules and methods to establish their government and keep it secure. We must bear in mind that nothing is —more difficult to set up, —more likely to fail, and —more dangerous to conduct, than a new system of government; because the bringer of the new system will make enemies of everyone who did well under the old system, while those who may do well under the new system still won’t support it warmly.

3:16: Why not?

NM: Partly because of fear of the opponents, who have the laws on their side, and partly because men are hard to convince of anything, and don’t really believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them.

3:16: Can’t these rulers work with others to succeed?

NM: If they need help they are sure to fail, and won’t achieve anything; but when they can rely on themselves and use force they aren’t running much risk. That’s why armed prophets always conquered, and the unarmed ones have been destroyed.

3:16: What’s the conceptual link between virtù and effective rule then?

NM: Fortune. She’s like one of our destructive rivers which, when it is angry, turns the plains into lakes, throws down the trees and buildings, takes earth from one spot, puts it in another; everyone flees before the flood; everyone yields to its fury and nowhere can repel it.

3:16: Can anything be done to prepare for this state of things?

NM: Of course. She shows her power where virtù and wisdom do not prepare to resist her, and directs her fury where she knows that no dykes or embankments are ready to hold her. It is better to be impetuous than cautious, because Fortuna is a woman and it is necessary, in order to keep her under, to beat and maul her.

3:16: Steady on there. I’m being triggered.

NM: Grow up. There’s no doubt that a prince becomes great when he overcomes difficulties and obstacles. For this reason, when fortuna wants greatness to come to a new prince (who needs a personal reputation more than an hereditary prince does), it causes enemies to arise and turns them against him; this gives him the opportunity to overcome them, climbing higher on this ladder that his enemies have brought to him! That’s why many people think that a wise prince should, when the opportunity presents itself, engineer some hostility against himself, so that he can crush it and thus elevate his level of fame.

3:16: Is fortuna the reason why princes lose their states?

NM: Princes who have lost their principalities after many years of possession shouldn’t blame their loss on fortuna. The real culprit is their own indolence, going through quiet times with no thought of the possibility of change (it’s a common human fault, failing to prepare for tempests unless one is actually in one!).

3:16: Is it your view that fortuna basically robs us of freewill? Fate seems to be in charge?

NM: I’m well aware that many men, past and present, have thought that the affairs of the world are governed by fortuna and by God in such a way that human prudence can’t get a grip on them and we have no way of protecting ourselves. These people hold that we needn’t sweat much over things, and that we should leave everything to chance. This opinion has been more widespread in our day because of the huge changes in affairs that we have seen and that are still going on—changes that no-one could have predicted. Sometimes when I think about this I am a little inclined that way myself. However, so as not to put our free will entirely out of business, I contend that fortuna decides half of our actions, leaving the other half—or perhaps a bit less—to our decisions.

Like I said earlier, I compare fortuna to one of those raging rivers but despite all that, when the weather turns fair ·and the river calms down· men can prepare for the next time by building dykes and dams so that when the river is next in flood it will stay within its banks, or at least not be so uncontrolled and damaging. That’s how it is with fortuna, which shows its power in places where virtù hasn’t made preparations to resist it: it sends its forces in directions where it knows that barriers and defences haven’t been raised to constrain it.

3:16: So rulers shouldn’t rely on fortuna, they shouldn’t hold fortuna totally responsible for what happens?

NM: We see that a prince can be happy today and ruined tomorrow without any change in himself; I think that this is to be explained mostly through the matter I have been discussing—a prince who relies entirely on fortuna is lost when it changes—but it may also be due to something else that I shall now present: A prince whose actions fit the spirit of the times will be successful, whereas one whose actions are out of tune with the times will fail.

3:16: Why do you think young men are better at dealing with fortuna than older ones?

NM: Fortuna changes, and men don’t change in their ways of going about things; so long as the two agree, men are successful; when they quarrel men are unsuccessful. I think that it is better to be adventurous than to be cautious, because fortuna is a woman, and if you want to stay on top of her you have to slap and thrust and it’s clear that she is more apt to submit to those who approach her in that way than to those who go about the business coolly. As a woman, she is always more partial to young men, because they are less cautious, more aggressive, bolder when they master her.

3:16: So is changing with the times important?

NM: I have many times considered that the causes of the good and bad fortunes of men depend on the manner of their proceeding with the times.

3:16: How does a ruler get prestige?

NM: Nothing builds a prince’s prestige more than his undertaking great enterprises and his setting a fine example ·by his personal conduct.

3:16: And how should he deal with flatterers?

NM: A wise prince will steer a different course between listening to flatterers and listening to everyone· - namely by assembling a cabinet of wise men and giving the freedom to tell him the truth only to them, and only in answer to questions he has put to them. But he should question them about everything, listen to their opinions, and then form his own conclusions.

3:16: Are there ways of becoming a ruler without virtù or fortuna?

NM: Of the ways in which a private person can rise to be a prince there are two that aren’t entirely matters of fortuna or virtù. Someone may raise himself to being a prince through some really wicked conduct. Alternatively, a citizen becomes the prince of his country by the support of his fellow-citizens. Of the first you’ll see little if anything that could be attributed to fortuna: he became a prince, as we have just seen, not through anyone’s favour but by steadily rising in the military profession, each promotion involving countless difficulties and dangers; and once he had his principality he held onto it, boldly, through many hostilities and dangers. And you won’t see anything you could attribute to virtù either, for it can’t be called virtù to kill one’s fellow-citizens, to deceive friends, to be without faith or mercy or religion; such methods may bring power but won’t bring glory.

3:16: Have you any examples of this sort of thing?

NM: Loads Richard! During the papacy of Alexander VI, Oliverotto da Fermo, wrote to ·his uncle· Giovanni Fogliani, to the following effect: Having been away from home for many years, he wanted to visit his uncle and his city, and to have a look at the land his father had left him. He hadn’t worked to acquire anything except honour, ·and so couldn’t return home with an ostentatious display of wealth·. But he wanted to return in style, so that the citizens should see he hadn’t been wasting his time in the military; so he would be accompanied by a hundred of his friends and servants, all on horseback; and he asked Giovanni to have the Fermians receive him with a suitable ceremony—to honour not only himself but also his uncle and guardian Giovanni. Giovanni ensured that his nephew received every courtesy. He caused him to be ceremoniously received by the Fermians, and lodged him in his own house.

After some days there, making the needed arrangements for his wicked plan, Oliverotto laid on a grand banquet to which he invited Giovanni Fogliani and the top men of Fermo. When the eating was over, and all the other entertainments that are usual in such banquets were finished, Oliverotto cunningly began some solemn talk about the greatness of Pope Alexander and his son Cesare, and of their enterprises; Giovanni and others joined in the conversation, but Oliverotto suddenly stood up and said that such matters should be discussed in a more private place; and he went into another room, with Giovanni and the other citizens following him. No sooner were they seated than soldiers emerged from hiding-places and slaughtered them all, Giovanni included. After this massacre Oliverotto ·and his followers· mounted on horseback and sped through the town to the palace of the governor; they laid siege to the palace, so frightening the governor that he was forced to obey him and form a government of which he (Oliverotto) made himself the prince.

Having killed all the dissentients who might hit back at him, he strengthened his position with new rules and regulations governing civil and military matters; so that in his one year as prince in Fermo he not only made himself secure within the city but also came to be feared by all his neighbours. He would have been as difficult to destroy as Agathocles was if he hadn’t—as I reported earlier — allowed himself to be deceived by Cesare Borgia, who netted him along with the Orsini and Vitelli at Sinigalia, where one year after the massacre, he was strangled, together with Vitellozzo, whom he had made his leader in virtù and wickedness.

3:16: Is cruelty in a ruler a bad thing then?

NM: I believe that it depends on whether cruelty is employed well or badly. Cruel acts are used well (if we can apply ‘well’ to wicked acts) if they are needed for political security and are all committed at a single stroke and then discontinued or turned into something that is to the advantage of the subjects. Cruel acts are badly used when, even if there are few of them at the outset, their number grows through time. Those who practise the first system may be able to improve somewhat their standing in the eyes of God and men, as Agathocles did. Those who follow the other can’t possibly maintain themselves. So someone who is seizing a state should think hard about all the injuries he’ll have to inflict, and get them all over with at the outset, rather than having cruelty as a daily occurrence.

3:16: And you have a theory that cruelty works well for the reputation of a ruler if he's taking over from a place used to benign rule don't you?

NM: Yes. To give reputation to a new ruler cruelty, treachery and irreligion are enough in a province where humanity, loyalty and religion have for a long time been common. Yet in the same way humanity, loyalty and religion are sufficient where cruelty, treachery and irreligion have dominated for some time, because, as bitter things disturb the taste and sweet ones cloy it, so men get bored with good and complain of ill. These causes, among others, opened Italy to Hannibal and Spain to Scipio, thus both of them found times and things suited to their way of succeeding. At that very time a man like Scipio would not have been succesful in Italy, or one like Hannibal so succesful in Spain as both were in the provinces where they acted.

3:16: Because Hannibal was cruel and Scipio humane?

NM: Yes.

3:16: What’s the other way you talked about being a ruler without virtu or fortuna?

NM: This where a citizen becomes the prince of his country not by wickedness or any intolerable violence, but by the favour of his fellow citizens. Now, this kind of principality—·this way of becoming a prince·—is obtained with the support of the common people or with the support of the nobles. Every city-state has common people who don’t want to be ruled or ordered around by the nobles, and nobles who do want to rule and order around the common people; and the conflict between these two opposite political drives results, in each city, in one of three things: a ·civil· principality, freedom or ungoverned chaos. Someone who becomes a prince through popular favour, then, ought to keep the people friendly towards him, and this isn’t difficult because all they ask of him is that he not oppress them.

But someone who becomes a prince through the favour of the nobles against the people’s wishes should make it his first priority to win the people over to himself. The bottom line is simply this: a prince must have the people friendly towards him; otherwise he has no security in difficult times. So a shrewd prince ought to handle things in such a way that his citizens will always, in all circumstances, need the government and need him; then he will always find them loyal.

3:16: What do you think should be the main preoccupation of any Prince then?

NM: War.

3:16: Huh?

NM: A prince oughtn’t to devote any of his serious time or energy to anything but war and how to wage it. This is the only thing that is appropriate for a ruler, and it has so much virtù that it not only enables those who are born princes to stay on their thrones but also, often, enables ordinary citizens to become princes. And on the other hand it’s clear that princes who have given more thought to life’s refinements than to arms have lost their states . There’s simply no comparison between an armed man and an unarmed one; and it is not reasonable to expect an armed man to be willing to obey one who is unarmed.

Nor is it reasonable to think that an unarmed man will be secure when he is surrounded by armed servants; with their contempt and his suspicions they won’t be able to work well together. So a prince who does not understand the art of war can’t be respected by his soldiers and can’t trust them. A prince, therefore, should never stop thinking about war, working at it even harder in times of peace than in wartime. He can do this in two ways—physically and mentally.

3:16: Isn’t money the key to war? If you have money, you’ll beat the guy that hasn’t got as much as you?

NM: That common opinion could not be more false which says that money is the sinew of war. If treasure should be enough to win, then Darius would have vanquished Alexander, the Greeks would have vanquished the Romans, and in our times Duke Charles would have vanquished the Swiss, and a few days ago the Pope and the Florentine together would not have had difficulty in defeating Francesco Maria, nephew of Julius II, in the war at Urbino. But all the above named were vanquished by those who esteemed not money, but good soldiers, as the sinew of war.

3:16: Is money then a sign of weakness if used to decide wars?

NM: Rome never acquired lands by means of money, but always through the virtu of their army. Signs by which the power of a State is recognized is to see how it lives with its neighbours; and if it is governed in a way that the neighbours , so as to have them friendly, are its pensioners, then it is a certain sign that that State is powerful: But when these said neighbours, although inferior to it, draw money from it, then it is a great sign of its weakness. It would be lengthy to recount how many times the Florentines, and the Venetians, and this Kingdom of France have bought themselves off in wars, and how many times they subjected themselves to an ignominy to which the Romans were subjected only one time.

3:16: How should a prince prepare physically for war?

NM: As well as keeping his men well organized and drilled, the prince should spend a lot of time hunting. Through this he can harden his body to strenuous exercise, and also learn about the terrain: how the mountains rise, how the valleys open out, how the plains lie, and the nature of rivers and marshes. All this should be studied with the greatest care.

3:16: And what mental preparations should he make for war?

NM: The prince should study historical accounts of the actions of great men, to see how they conducted themselves in war; he should study the causes of their victories and defeats, so as to avoid the defeats and imitate the victories; and above all he should model himself on some great man of the past, a man who no doubt modelled his conduct on some still earlier example, as it is said Alexander the Great modelled himself on Achilles, Caesar on Alexander, and Scipio on Cyrus.

3:16: Are you endorsing all of this or just describing what rulers actually do?

NM: I believe the true way of going to Paradise would be to learn the road to hell in order to avoid it. We may want a preacher who is prudent, blameless and true but I like to show one crazier than Ponzo, more crafty than Fra Girolamo, more of a hypocrite than Frate Alberto! My aim is to write things that will be useful the reader who understands them; so I find it more appropriate to pursue the real truth of the matter than to repeat what people have imagined about it. Many writers have dreamed up republics and principalities such as have never been seen or known in the real world. ·And attending to them is dangerous·, because the gap between how men live and how they ought to live is so wide that any prince who thinks in terms not of how people do behave but of how they ought to behave will destroy his power rather than maintaining it. A man who tries to act virtuously will soon come to grief at the hands of the unscrupulous people surrounding him. Thus, a prince who wants to keep his power must learn how to act immorally, using or not using this skill according to necessity.

3:16: So a ruler has to be bad if being good will lead him to lose power?

NM: A prince has to be wary in avoiding the vices that would cost him his state. He should also avoid as far as he can the vices that would not cost him his state, but he can’t fully succeed in this, so he shouldn’t worry too much about giving himself over to them. And he needn’t be anxious about getting a bad reputation for vices without which it would be hard for him to save his state: all things considered, there’s always something that looks like virtù but would bring him to ruin if he adopted it, and something that looks like vice but would make him safe and prosperous.

3:16: So vice can be useful?

NM: Everything great that has been done in our time was the work of someone who was regarded as a miser; other people’s attempts at great things have all failed. As long as a prince keeps his subjects united and loyal, therefore, he oughtn’t to mind being criticised as ‘cruel’; because with a very few examples ·of punitive severity· he will be showing more ·real· mercy than those who are too lenient, allowing a breakdown of law and order that leads to murders or robberies.

3:16: Isn’t it better to be loved than feared?

NM: When a choice has to be made it is safer to be feared. The reason for this is a fact about men in general: they are ungrateful, fickle, deceptive, cowardly and greedy. As long as you are doing them good, they are entirely yours: they’ll offer you their blood, their property, their lives, and their children—as long as there is no immediate prospect of their having to make good on these offerings; but when that changes, they’ll turn against you. And a prince who relies on their promises and doesn’t take other precautions is ruined. Friendships that are •bought, rather than •acquired through greatness or nobility of mind, may indeed be earned—bought and paid for—but they aren’t secured and can’t be relied on in time of need. And men are less hesitant about letting down someone they love than in letting down someone they fear, because love affects men’s behaviour only through the thought of how they ought to behave, and men are a low-down lot for whom that thought has no power to get them to do anything they find inconvenient; whereas fear affects their behaviour through the thought of possible punishment, and that thought never loses its power. Still, a prince should try to inspire fear in such a way that if he isn’t loved he at least isn’t hated, because being feared isn’t much of a burden if one isn’t hated.

3:16: Is there any evidence for all this?

NM: Take Hannibal again. Hannibal has been praised for, among much else, the fact that he led an enormous mixed-race army to fight in foreign lands, and never—in times of bad or of good fortuna—had any troubles within the army or between the army and himself. The only possible explanation for this is his inhuman cruelty, which combined with his enormous virtù to make him an object of respect and terror for his soldiers. He couldn’t have achieved this just through his other virtùs, without the cruelty. Historians who have admired his achievements while condemning ·the cruelty that was· their principal cause haven’t thought hard enough.

3:16: What about lying? Should rulers be truthful?

NM: Our recent experience has been that the princes who achieved great things haven’t worried much about keeping their word. Knowing how to use cunning to outwit men, they have eventually overcome those who have behaved honestly. Pope Alexander VI was deceptive in everything he did—used deception as a matter of course—and always found victims. No man ever said things with greater force, reinforcing his promises with greater oaths, while keeping his word less; yet his deceptions always worked out in the way he wanted, because he well understood this aspect of mankind. A prince needn’t have all the good qualities but he does need to appear to have them.

3:16: How’s he to avoid being hated?

NM: A prince won’t be hated as long as he keeps his hands off his subjects’ property and their women. What would most get him hated (I repeat) is his being a grabber, a thief of his subjects’ property and women; he mustn’t do that. Most men live contentedly as long as their property and their honor are untouched.

3:16: Is it your view that men actually don’t know how to be entirely good or entirely bad?

NM: Yes. Men do not know how to be entirely bad or perfectly good, and that when an evil has some greatness in it or is generous in any part, they do not know how to attempt it. Thus Giovanpagolo, who did not mind being publicly called incestuous and a parricide, did not know how, or better, did not dare to make an enterprise where everyone would have admired his courage and which would have left an eternal memory of himself.

3:16: You say he must look good even if he’s not? What mustn’t he look like?

NM: A prince will be condemned if he is regarded as variable, frivolous, effeminate and cowardly, irresolute; and the prince should steer away from all these as though they were a reef ·on which his ship of state could be wrecked.

3:16: What should he appear as?

NM: He should try to show in his actions greatness and courage, seriousness, and fortitude; and in his private dealings with his subjects his judgments should be irrevocable, and his standing should be such that no-one would dream of trying to cheat or outwit him.

3:16: By doing this do you think conspiracies against his rule are weakened?

NM: Of course. On the conspirator’s side there is nothing but fear, jealousy, and the terrifying prospect of punishment; on the prince’s side there is the majesty of his rank, the laws, and the protection of his friends and the state. Add to these factors the good will of the people and it’s almost impossible that anyone should be so rash as to conspire against a prince.

3:16: But didn’t some good Roman Emperors get killed by conspirators despite doing all that?

NM: Ah well, whereas in other states the prince has only to deal with the ambition of the nobles and the insolence of the common people, the Roman emperors had a third problem, created by the cruelty and greed of their soldiers. It wasn’t easy to satisfy both the common people, who loved peace and were drawn to unambitious princes, and the soldiers, who were drawn to princes who were bold, cruel, and rapacious, and were quite willing for a prince to exercise these qualities against the common people, so that they could double their incomes by adding loot to their regular pay and give vent to their own greed and cruelty.

3:16: Has religion a role in this?

NM: Church states are backed by ancient religious institutions that are so powerful and of such a character that their princes can stay in power no matter how they behave and live. These are the only princes who have states that they don’t defend, and subjects whom they don’t rule; and the states, although unguarded, are not taken from them, and the subjects don’t mind not being ruled and don’t want to alienate themselves and have no way of doing so. These are the only principalities that are secure and happy. But they’re upheld by ·divine· powers to which the human mind can’t reach, so I shan’t say anything more about them.

3:16: No, I mean, does religion in a non-church state have a role in how states should be ruled?

NM: Well, whoever considers well Roman history will see how much Religion served in commanding the armies, in reuniting the plebs, both in keeping men good, and in making the wicked ashamed. For Romulus to institute the Senate and to make the other civil and military arrangements, the authority of God was not necessary, but it was very necessary for Numa, who pretended he had met with a Nymph who advised him of that which he should counsel the people; and all this resulted because he wanted to introduce new ordinances and institutions in that City, and was apprehensive that his authority was not enough. And truly there never was any extraordinary institutor of laws among a people who did not have recourse to God, because otherwise he would not have been accepted; for though these laws are very well known by prudent men, by themselves they do not contain evident reasons capable of persuading others. Wise men who want to remove this difficulty, therefore, have recourse to God. Thus did Lycurgus, thus Solon, thus many others who had the same aims as they.

The Religion introduced by Numa was among the chief reasons for the felicity of Rome, for it caused good ordinances, good ordinances make good fortune, and from good fortune there arises the happy successes of the enterprises. And as the observance of divine institutions is the cause of the greatness of Republics, so the contempt of it is the cause of their ruin, for where the fear of God is lacking it will happen that that kingdom will be ruined or that it will be sustained through fear of a Prince, which may supply the want of Religion. And because Princes are short lived, it will happen that that Kingdom will easily fall as he fails in virtu. Hence Kingdoms which depend solely on the virtu of one man are not durable for long because that virtu fails with the life of that man, and it rarely happens that it is renewed in his successor, as Dante prudently says: Rarely there descends from the father to son human probity, and this is the will of the one who gives it, because it is asked alone from him.

The welfare of a Republic or a Kingdom, therefore, is not in having a Prince who governs prudently while he lives, but one who organizes it in a way that, if he should die, it will still maintain itself. And although crude men are more easily persuaded by new ordinances and opinions, yet it is not impossible because of this to persuade civilized men who presume themselves not to be crude. The people of Florence did not seem either crude or ignorant, none the less Brother Girolamo Savonarola was persuaded that he talked with God. I do not want to judge whether that was true or not, because one ought not to talk of so great a man except with reverence. But I may well say that an infinite number believed him without they having seen anything extraordinary which would make them believe, because his life, the doctrine, the subjects he took up were sufficient to make them have faith. Let no one be dismayed, therefore, if he is not able to attain that which had been attained by others, for men are born, live, and die, always in the same way.

3:16: So should rulers look after religion if they can?

NM: Those Princes or those Republics that want to maintain themselves uncorrupted, have above everything else to maintain uncorrupted the services of Religion, and hold them always in veneration. For no one can have a better indication of the ruin of a province than to see the divine institutions held in contempt.

3:16: So you see religion as a useful political tool?

NM: It is. The Roman people having created the Tribunes with Consular Power, and all but one selected from the Plebs, and pestilence and famine having occurred there that year, and certain prodigies coming to pass, the Nobles used this occasion of the creation of the new Tribunes, saying that the Gods were angered because Rome had ill-used the majesty of its Empire, and that there was no other remedy to placate the Gods than by returning the election of the Tribunes to its own original place; from which the Plebs, frightened by this Religion, created all the Tribunes from the class of the Nobles.

3:16: Which religions are best for a republic then?

NM: In ancient times the people were greater lovers of liberty than in these times, I believe it results from the same reason which makes men presently less strong, which I believe is the difference between our education and that of the ancients, founded on the difference between our Religion and the ancients. For, as our Religion shows the truth and the true way of life, it causes us to esteem less the honors of the world: while the Gentiles and Pagans, esteeming them greatly, and having placed the highest good in them, were more ferocious in their actions. Which can be observed from many of their institutions, beginning with the magnificence of their sacrifices as compared to the humility of ours, in which there is some pomp more delicate than magnificent, but no ferocious or energetic actions. Theirs did not lack pomp and magnificence of ceremony, but there was added the action of sacrifice full of blood and ferocity, the killing of many animals, which sight being terrible it rendered the men like unto it.

In addition to this, the ancient Religion did not beatify men except those full of worldly glory, such as were the Captains of armies and Princes of Republics. Our Religion has glorified more humble and contemplative men rather than men of action. It also places the highest good in humility, lowliness, and contempt of human things: the other places it in the greatness of soul, the strength of body, and all the other things which make men very brave. And, if our Religion requires that there be strength of soul in you, it desires that you be more adept at suffering than in achieving great deeds. This mode of living appears to me, therefore, to have rendered the world weak and a prey to wicked men, who can manage it securely, seeing that the great body of men, in order to go to Paradise, think more of enduring their beatings than in avenging them. And although it appears that the World has become effeminate and Heaven disarmed, yet this arises without doubt more from the baseness of men who have interpreted our Religion in accordance with Indolence and not in accordance with Virtu.

For if they were to consider that our Religion permits the exaltation and defence of the country, they would see that it desires that we love and honour our country, and that we prepare ourselves so that we can be able to defend her. This education and false interpretations, therefore, are the cause that in the world as many Republics are not seen in them that the people have as much love for liberty now as at that time.

3:16: So what kinds of republican states are there?

NM: I will talk of those which have had their beginning far removed from any external servitude, but which were initially governed themselves through their own will, either as Republics or as Principalities; which have had as diverse origins diverse laws and institutions. Some who have written of Republics say there are one of three States in them called by them Principality -Monarchy, of the Best -Aristocracy, and Popular -Democracy, and that those men who institute laws in a City ought to turn to one of these, according as it seems fit to them. Some others ,and wiser according to the opinion of many, believe there are six kinds of Governments, of which some are very bad, and some are good in themselves, but may be so easily corrupted that they also become pernicious.

Those that are good are the three mentioned above: those that are bad are three others which derive from those first three, and each is so similar to them that they easily jump from one to the other, for the Principality easily becomes a tyranny, autocracy easily become State of the Few - oligarchies, and the Popular Democracy without difficulty is converted into a licentious one - anarchy.

3:16: Is it important for a good Republican state to distribute powers between the different groups?

NM: Yes. Lycurgus, who so established his laws in Sparta, in giving parts to the King, the Aristocracy, and the People, made a state that endured more than eight hundred years, with great praise to himself and tranquillity to that City. The contrary happened to Solon who established the laws in Athens, and who by establishing only the Popular Democratic state, he gave it such a brief existence that before he died he saw arise the tyranny of Pisistratus.

3:16: Is Rome an ideal model of the Republican state for you?

NM: Yes. For, if Rome did not attain top fortune, it attained the second; if the first institutions were defective, none the less they did not deviate from the straight path which would lead them to perfection, for Romulus and all the other Kings made many and good laws, all conforming to a free existence. But because their objective was to found a Kingdom and not a Republic, when that City became free she lacked many things that were necessary to be established in favor of liberty, which had not been established by those Kings.

And although those Kings lost their Empire none the less those who drove them out quickly instituted two Consuls who should be in the place of the King, and so it happened that while the name of King was driven from Rome, the royal power was not; so that the Consuls and the Senate existed in forms mentioned above, that is the Principate and the Aristocracy. There remained only to make a place for Popular government because the people rose against them: so that in order not to lose everything, the Nobility was constrained to concede a part of its power to them, and on the other hand the Senate and the Consuls remained with so much authority that they were able to keep their rank in that Republic. And thus was born the Tribunes of the plebs, government of that Republic came to be more stable, having a part of all those forms of government.

And so favorable was fortune to them that although they passed from a Monarchial government and from an Aristocracy to Democracy, by those same degrees and for the same reasons that were discussed above, none the less the Royal form was never entirely taken away to give authority to the Aristocracy, nor was all the authority of the Aristocrats diminished in order to give it to the People, but it remained shared between the three it made the Republic perfect: a perfection that resulted from the disunion of the Plebs and the Senate.

3:16: How important is liberty?

NM: It’s the key. That’s why, among the more necessary things instituted by those who have prudently established a Republic, is to establish a guard to liberty. A Prince wanting to gain over to himself a people who are hostile to him ought first to look into what the people desire, and he will find they always desire two things: the one, to avenge themselves against those who are the cause of their slavery: the other, to regain their liberty. The first desire the Prince is able to satisfy entirely, the second in part. All the towns and provinces which are free in every way make the greatest advances. For here greater populations are seen because marriages are more free and more desired by men, because everyone willingly procreates those children that he believes he is able to raise without being apprehensive that their patrimony will be taken away, and to know that they are not only born free and not slaves, but are also able through their own virtu to become Princes.

They will see wealth multiplied more rapidly, both that which comes from the culture of the soil and that which comes from the arts, for everyone willingly multiplies those things and seek to acquire those goods whose acquisition he believes he can enjoy. Whence it results that men competing for both private and public betterment, both come to increase in a wondrous manner .

3:16: Are the corrupt ways of monarchs a problem for establishing liberty in a republic?

NM: Yes. I judge that it was necessary that Kings should be eliminated in Rome, or else that Rome would in a very short time become weak and of no valor; for considering to what degree of corruption those Kings had come, if it should have continued so for two or three successions, and that that corruption which was in them had begun to spread through its members; and as the members had been corrupted it was impossible ever again to reform the state. But losing the head while the torso was sound, they were able easily to return to a free and ordered society. After Rome had driven out her Kings, she was no longer exposed to those perils resulting from a succession of weak or bad Kings; for the highest authority was vested in the Consuls, who came to that Empire not by heredity or deceit or violent ambition, but by free suffrage, and were always most excellent men, from whose virtu and fortune Rome had benefited from time to time, and was able to arrive at her ultimate greatness in as many years as she had existed under her Kings.

For it is seen that two continuous successions of Princes of virtù are sufficient to acquire the world, as was the case of Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great. A Republic ought to be able to do so much more, having the means of electing not only two successions, but an infinite number of Princes of great virtu who are successors one after the other: which succession of virtu is always well established in every Republic.

3:16: What does a good ruler deliver?

NM: A Prince secure in the midst of secure citizens, he will see the world full of peace and justice, he will see the Senate with its authority, the Magistrates with their honor, rich citizens enjoying their wealth, nobility and virtu exalted, he will see every quiet and good, where everyone can hold and defend whatever opinion he wishes: In the end, he will see the triumph of the world, the Prince full of reverence and glory, the people full of love and security.

3:16: Does a good republic like your Roman one depend more on virtù than fortune?

NM: Many authors, among whom is that most serious writer Plutarch, have had the opinion that the Roman people in acquiring the Empire were favored more by Fortune than by virtù. And among other reasons which he cities, he says that, by the admission of that people, it can be shown that they ascribed all their victories to Fortune, as they had built more temples to Fortune than to any other God. I completely disagree with this.

3:16: Why?

NM: It was the virtù of the armies that enabled her to acquire that Empire; and the order of proceeding and her own institutions founded by her first Legislator that enabled her to maintain the acquisitions. We always see mixed with Fortune a very great Virtu and Prudence.

3:16: How should foreigners be treated? I ask this because there's a lot of talk about immigration and population movements these days.

NM: Those who plan for a City to achieve great Empire ought with all industry to endeavor to make it full of inhabitants, for without this abundance of men, one can never succeed in making a City great. This is done in two ways, by love and by force. Through love, by keeping the ways open and secure for foreigners who should plan to come to live there. Through force, by destroying the neighboring Cities and sending their inhabitants to live in your City.

3:16: And is all history the propaganda of the victors?

NM: To those philosophers who hold that the world has existed from eternity, I believe it is possible to reply, that, if such great antiquity was true, it would be reasonable that there should be some record of more than five thousand years, except it is seen that the records of those times have been destroyed from diverse causes: of which some were acts of men, some of Heaven. Those that are acts of men are the changes of the sects of religion and of languages. Because, when a new sect springs up, that is, a new Religion, the first effort is, in order to give itself reputation, to extinguish the old; and if it happens that the establishers of the new sect are of different languages, they extinguish it the old easily. Which thing is known by observing the method which the Christian Religion employed against the heathen sect, which has cancelled all its institutions, all of its ceremonies, and extinguished every record of that ancient Theology.

3:16: Although you say that monarchs have to go because eventually they’ll be corrupt, you seem to like the French monarchy.

NM: Well, the kingdom of France is moderated more by laws than any other kingdom of which at our time we have knowledge. The kingdom of France lives under laws and orders more than any other kingdom. These laws and orders are maintained by Parliaments, notably that of Paris: by it they are renewed any time it acts against a prince of the kingdom or in its sentences condemns the king. And up to now it has maintained itself by having been a persistent executor against that nobility.

3:16: But though you like the rule of law, such monarchies can’t give complete liberty to the people can it?

NM: No. As far as the popular desire of recovering their liberty, the prince, not being able to satisfy them, must examine what the reasons are that make them desire being free.

3:16: Mind you, you think a few people want to be free just so they can rule others don’t you?

NM: I do, but all the others, who are infinite, desire liberty in order to live securely.

3:16: Can a monarchy gift that?

NM: No.

3:16: Why not?

NM: For those whom it is enough to live securely (vivere sicuro is the phrase I use here Richard), they are easily satisfied by making orders and laws that, along with the power of the king, comprehend everyone's security. And once a prince does this, and the people see that he never breaks such laws, they will shortly begin to live securely and contentedly. So in France the people live securely for no other reason than that its kings are bound to infinite laws in which the security of all their people is comprehended.

3:16: So security is distinct from liberty and really we should try and have both.

NM: Of course.

3:16: But the French monarch himself lives as a tributary to foreign mercenaries according to you doesn’t he? The monarchy can’t deliver full liberty because of this dependence on foreigners according to you?

NM: This all comes from having disarmed his people and having preferred to enjoy the immediate profit of being able to plunder the people and of avoiding an imaginary rather than a real danger, instead of doing things that would assure them and make their states perpetually happy. This disorder, if it produces some quiet times, is in time the cause of straitened circumstances, damage and irreparable ruin. The king of France has disarmed his people in order to be able to command them more easily, and such a policy is a defect in that kingdom, for failure to attend to this matter is the one thing that makes her weak.

3:16: Would they be better off keeping the population armed then?

NM: Present Princes and modern Republics, who lack their own soldiers in regard to defence and offence, ought to be ashamed of themselves. So yes. Rome was free four hundred years and was armed; Sparta, eight hundred; many other cities have been unarmed and free less than forty years. No new prince has ever disarmed his subjects. Rather, when any new prince has found the people unarmed he has armed them.

3:16: Why?

NM: Because, by arming them you make those arms yours: the men whom you distrusted become loyal, those who were already loyal remain so, and your subjects become your supporters. Not all the subjects can be armed, and those who are armed are receiving a privilege, but this won’t get you into trouble with the others. They will understand that the armed men are bound to you, are likely to be put in harm’s way on your behalf, and so deserve a greater reward; and they won’t hold it against you that you gave given some and not others this privilege.

3:16: This links with your ideas about the kind of army a ruler has doesn’t it? You think it matters what kind of army they have don’t you?

NM: It matters greatly, and that when armed force is to be used by a prince then the prince ought to go in person and put himself in command of the army. And when a republic goes to war, it has to send its citizens as commanders; when one is sent who doesn’t turn out satisfactorily, he should be recalled; and when a commander turns out to be very capable, there should be laws that forbid him to exceed his assigned authority. Experience has shown princes and republics with their own armies doing extremely well, and mercenaries doing nothing but harm. And it is harder for a citizen to seize control of a republic that has its own army than to do this with a republic that relies on foreign troops. Rome and Sparta stood for many ages armed and independent. The Swiss today are completely armed and entirely independent.

3:16: But didn’t the Venetians and Florentines do well using mercenaries?

NM: The Florentines were favoured by chance: of the virtuosi commanders who might have been threats, some weren’t victorious, some met with opposition, and others turned their ambitions elsewhere. One who wasn’t victorious was John Hawkwood; and since he didn’t conquer, his loyalty can’t be proved; but everyone will agree that if he had conquered, the Florentines would have been at his mercy.

As for the Venetians: if we look at their achievements we see that they fought confidently and gloriously so long as they made war using their own men, with nobles and armed commoners fighting valiantly. That was in sea-battles. When they began to fight on land, they forsook this virtù and followed the Italian custom of hiring mercenaries. In the early stages of their expansion on land they had little to fear from their mercenary commanders because they didn’t have much territory ·for the commanders to eye greedily, and because of their great reputation which will have scared off any mercenary who wanted to go up against them·. But when their domain expanded, as it did under Carmignuola, they got a taste of the trouble that mercenaries can bring.

3:16: What's the story of this Carmignuola?

NM: They saw what a virtuoso soldier he was -they beat the Duke of Milan under his leadership; but they also saw that he was becoming lukewarm about the war against Milan, and were afraid that he wouldn’t bring them any more victories because he was no longer victory-minded. So they didn’t want to keep him on their payroll, but· they wouldn’t—couldn’t—just dismiss him, because that would threaten them with the loss of all the territory they had gained, the threat coming from an enemy whose army was commanded by the able Carmignuola. To keep themselves safe, therefore, their only option was to kill him. They recalled him to Venice for consultations, then accused him of treason, and tried and beheaded him.

3:16: But wouldn’t an armed citizenship always fight for their liberty and threaten to take down even the monarch.

NM: Yes.

3:16: Does keeping the citizens armed prevent citizens from becoming passive, and is this active spirit the core ingredient to a true Republic?

NM: Yes. To me those who condemn the tumults between the Nobles and the Plebs seem to be cavilling at the very thing that was the primary cause of Rome's retention of liberty. And they do not realize that in every republic there are two different dispositions, that of the people and that of the great men, and that all legislation favoring liberty is brought about by their dissension. Enmities between the people and the Senate should, therefore, be looked upon as an inconvenience which it is necessary to put up with in order to arrive at the greatness of Rome. Republics always need a creative tension.

3:16: So the attack on the White House by a Rebublican mob of Trump supporters are healthy for the republic and bring about better laws and a stronger Republic?

NM: Yes.

3:16: So you think you can trust the people over the political leaders?

NM: A people is more prudent, more stable, and of better judgment than a prince.

3:16: Do you think then that liberty is more important than security to a Roman type of Republicanism?

NM: Yes.

3:16: So how does a Republic of this kind maintain order and not fall into anarchy?

NM: The Romans were able to maintain liberty and order because of the people's ability to discern the common good when it was shown to them. At times when ordinary Roman citizens wrongly supposed that a law or institution was designed to oppress them, they could be persuaded that their beliefs are mistaken through the remedy of assemblies, in which some man of influence gets up and makes a speech showing them how they are deceiving themselves.

3:16: So this is Biden’s role I guess.

NM: Well, as Tully says, the people, although they may be ignorant, can grasp the truth, and yield easily when told what is true by a trustworthy man.

3:16: So we must trust the competency of the people?

NM: Like I said, people are prudent, stable and grateful. Vox populi, vox dei as we say! Public opinion is remarkably accurate in its prognostications. With regard to its judgment, when two speakers of equal skill are heard advocating different alternatives, very rarely does one find the people failing to adopt the better view or incapable of appreciating the truth of what it hears.

3:16: Are you serious?

NM: The people can never be persuaded that it is good to appoint to an office a man of infamous or corrupt habits, whereas a prince may easily and in a vast variety of ways be persuaded to do this.

3:16: Trump? Bolsonaro? Johnson?

NM: Huh?

3:16: Hitler?

NM: Look Richard, An uncontrolled and tumultuous people can be spoken to by a good man and easily led back into a good way. But no one can speak to a wicked prince, and the only remedy is steel. To cure the malady of the people words are enough.

3:16: When dealing with uprisings and the like, should we punish them?

NM: It’s complicated. The Roman Republic was disturbed by the enmity between the Nobles and the Plebs: none the less, when a war occurred to them, they sent out Quintius and Appius Claudius with the armies. Appius, because he was cruel and rude in commanding, was ill obeyed by his soldiers, so that being almost overcome he fled from his province. Quintius, because he was a benign and humane disposition, had his soldiers obedient to him, and brought back the victory. So it appears that it is better to be humane than haughty, gentle than cruel, when governing a multitude. None the less, Cornelius Tacitus in one of his opinions concludes the contrary, when he says: In governing the multitude Punishment is worth more than Obsequies.

In considering if it is possible to reconcile both of these opinions, I say that you have to rule men who ordinarily are colleagues, or men who are always your subjects. If they are your colleagues, punishment cannot entirely be used, nor that severity which Cornelius recommends: and as the Roman Pleb had equal sovereignty with the Nobility in Rome, anyone who had temporarily become a Prince could not manage them with cruelty and rudeness. And many times it is seen that better results were achieved by the Roman Captains who made themselves beloved by the armies, and who managed them with obsequies, than those who made themselves extraordinarily feared, unless they were already accompanied by an excessive virtu, as was Manlius Torquatus.

But he who commands subjects - of whom Cornelius talks about- ought to turn rather to punishment than to gentleness, so that they should not become insolent and trample on you, because of your too great easiness. But this also ought to be moderate so that hatred is avoided, as making himself hated never returns good to a Prince. And the way of avoiding hatred is to let the property of the subjects alone, as we’ve discussed earlier.

3:16: And in particular, don’t mess about with their women.

NM: Exactly. Women have been the cause of many ruinations, and have done great damage to those who govern a City, and have caused many divisions in them: the excess committed against Lucretia deprived the Tarquins of their State; and those committed against Virginia deprived the Ten Decemvirs of their authority. And Aristotle places the injury committed on Women, either by seduction, by violence, or corruption of marriages among the first causes of the ruin of the Tyrants.

3:16: So you don’t think being cruel and cynical is always the best way to behave?

NM: It’s not realistic. Some times an act of humanity, full of charity, can have more influence on the minds of men than a ferocious and violent act; and that many times that province and that City, which, with arms, instruments of war, and every other human power, could not be conquered, was conquered by an example of humanity, of mercy, of chastity, or of generosity.

3:16: Do you think that in certain extraordinary times, such as war or a pandemic, a Republic might resort to special powers and suspend the usual laws?

NM: No Republic will be perfect, unless it has provided for everything with laws, and provided a remedy for every incident, and fixed the method of governing it. And therefore I say that those Republics which in urgent perils do not have resort either to a Dictatorship or a similar authority, will always be ruined in grave incidents. But in a Republic, it should never happen that it be governed by extraordinary methods. For although the extraordinary method would do well at that time, none the less the example does evil, for if a usage is established of breaking institutions for good objectives, then under that pretext they will be broken for evil ones.

Those Romans who introduced the method of creating a Dictator have been condemned by some writers, as something that was in time the cause of tyranny in Rome; alleging that the first tyrant who existed in that City commanded her under this title of Dictator, saying if it had not been for this, Caesar could not under any public title have imposed his tyranny. But it is seen that the Dictatorship while it was given according to public orders and not by individual authority always did good to the City. In Rome no Dictator did anything that was not good for the Republic.

3:16: So it has to be a temporary thing and mustn’t be linked to an individual, like a Trump, a Hitler, a Bolsonaro?

NM: Yes. If a Citizen would want to take up authority in an irregular manner, he’d have to have many qualities which he can never have in an uncorrupted Republic, for he needs to be very rich and to have many adherents and partisans, which he cannot have where the laws are observed: and even if he should have them, such men are so formidable that free suffrage would not support them. In addition to this, a Dictator was made for a limited time and not in perpetuity, and only to remove the cause for which he was created; and his authority extended only in being able to decide by himself the ways of meeting that urgent peril, to do things without consultation, and to punish anyone without appeal; but he could do nothing to diminish the power of the State, such as would have been the taking away of authority from the Senate or the people, to destroy the ancient institutions of the City and the making of new ones.

So that taking together the short time of the Dictatorship and the limited authority that he had, and the uncorrupted Roman People, it was impossible that he should exceed his limits and harm the City: but from experience it is seen that the City always benefited by him.

3:16: Dictators are not the same as tyrants are they?

NM: When a Dictator was created there remained the Tribunes, Consuls, and the Senate, with all their authority, and the Dictator could not take it away from them; and even if he should have been able to remove anyone from the Consulship, or from the Senate, he could not suppress the Senatorial order and make new laws. So that the Senate, the Consuls, and the Tribunes, remaining with their authority, came to be as his guard to prevent him from going off from the right road.

But in the creation of the Ten Tyrants all the contrary occurred, for they annulled the Consuls and the Tribunes, and they were given authority to make laws and do every other thing as the Roman People had. So that, finding themselves alone, without Consuls, without Tribunes, without the appeal to the People, and because of this not having anyone to observe them, moved by the ambitions of Appius, they were able in the second year to become insolent.

3:16: We’ve got recent examples – Boris Johnson for one - of people not willing to obey their own laws. What do you make of that?

NM: I do not believe there is a worse example in a Republic than to make a law and not to observe it, and much more when it is not observed by those who made it.

3:16: What’s the best way of dealing with insolent would-be rulers who spring up, like Johnson and Trump?

NM: There cannot exist in a Republic, and especially in those that are corrupt, a better method, less troublesome and more easily opposed to the ambitions of any citizen, than to block the paths to the rank he wants.

3:16: We’ve got people at the moment who seem to actively oppose laws on taxation, health care, vaccines, welfare provision generally that would help them and instead support things that make life harder for themselves. What can be done when people seem to want things that will harm them?

NM: Many times, deceived by a false illusion of good, the People desire their own ruin, and unless they are made aware of what is bad and what is good by someone in whom they have faith, the Republic is subjected to infinite dangers and damage. And if chance causes People not to have faith in anyone - as occurs sometimes, having been deceived before either by events or by men- their ruin comes of necessity. As Dante says in On Monarchy, the People many times shout, Life to their death and death to their life.

It has to be said that those who have found themselves witnesses of the deliberations of men have observed, and still observe, how often the opinions of men are erroneous and many times, if they are not decided by very excellent men, are contrary to all truth.

3:16: What should Trump have done when faced with his supporters wanting an uprising?

NM: He who is in charge of an army, or he who finds himself in a City where a tumult has arisen, ought to present himself there with as much grace and as honorably as he can, attiring himself with the insignia of his rank which he holds in order to make himself more revered.

3:16: So Trump did the opposite of what you recommend! Ok. Is it because people are corruptible that you think we need Republics on the model of Rome?

NM: Yes.

3:16: Why a republic not a prince?

NM: Well, firstly, a republic is better able to adapt itself to diverse circumstances than a prince owing to the diversity found among its citizens.

3:16: So is being able to draw on a range of different leaders depending on circumstances the benefit of the republican way of leadership?

NM: Yes. If Fabius had been king of Rome, he might easily have lost the war, since he was incapable of altering his methods according as circumstance changed. Since, however, he was born in a republic where there were diverse citizens with diverse dispositions, it came about that, just as it had a Fabius, who was the best man to keep the war going when circumstances required it, so later it had a Scipio at a time suited to its victorious consummation.

3:16: Don’t republican institutions also have a limited ability to be flexible?

NM: Yes. Institutions in republics do not change with the times but change very slowly because it is more painful to change them since it is necessary to wait until the whole republic is in a state of upheaval; and for this it is not enough that one man alone should change his own procedure.

3:16: The American Republic has a story that everyone can make it to the top and make great fortunes if they work hard. This is the American Dream. Is this a Roman ideal?

NM: It sounds idiotic. I believe it to be a most true thing that it rarely or never happens that men of little fortune come to high rank without force and without fraud, unless that rank to which others have come is not obtained either by gift or by heredity. Nor do I believe that force alone will ever be found to be enough; but it will be indeed found that fraud alone will be enough; as those will clearly see who read the life of Philip of Macedonia, that of Agathocles the Sicilian, and many such others, who from the lowest, or rather low, fortune have arrived either to a Kingdom or to very great Empires. The Romans in their first expansions did not lack using fraud; which has always been necessary for those to use who, from small beginnings, want to rise to sublime heights, which is less shameful when it is more concealed, as it was with the Romans.

3:16: There’s a lot about inequality these days, and also about the bloated riches of the plutocracy and the vast riches of our political leaders. Shouldn’t we be looking to make everyone well off?

NM: The most useful thing which is established in a republic is that its Citizens are to be kept poor. And although there did not appear to be those ordinances in Rome which would have that effect - the Agrarian law especially having had so much opposition- none the less, from experience, it is seen that even after four hundred years after Rome had been founded, there still existed a very great poverty; nor can it be believed that any other great institution caused this effect than to observe that poverty did not impede the way to you to any rank or honor, and that merit and virtu could be found in any house they lived in, which manner of living made riches less desirable.

This is manifestly seen when the Consul Minitius with his army was besieged by the Equeans, Rome was full of apprehension that the army should be lost, so that they had recourse to the creation of a Dictator, their last remedy in times of affliction. And they created L. Quintius Cincinnatus Dictator, who was then to be found on his little farm, which he worked with his own hands. This event is celebrated in words of gold by T. Livius, saying, Let everyone not listen to those who prefer riches to everything else in the world and who think there is neither honor nor virtu where wealth does not flow.

Cincinnatus was working on his little farm, which did not exceed beyond four jugeri, when the Legate came from Rome to announce to him his election to the Dictatorship, and to show him in what peril the Roman Republic found itself. He put on his toga, went to Rome and gathered an army, and went to liberate Minitius; and having routed and despoiled the army, and freed Minitius, he did not want the besieged army to share in the booty, saying these words to them: I do not want you to share in the booty of those to whom you had been about to become prey.

3:16: Doesn’t what you say about Republics contradict what you say about Princes in ‘The Prince’?

NM: No. I say that the States of the Princes have lasted a long time, the States of the Republics have lasted a long time, and both have had need to be regulated by laws; for a Prince who can do what he wants is a madman, and a People which can do as it wants to is not wise. If, therefore, discussion is to be had of a Prince obligated by laws, and of a People unobligated by them, more virtu will be observed in the People than in Princes: if the discussion is to be had of both loosened from such control, fewer errors will be observed in the People than in the Princes, and those that are fewer have the greater remedies: For a licentious and tumultuous People can be talked to by a good man, and can easily be returned to the good path: but there is no one who can talk to a Prince, nor is there any other remedy but steel sword. From which the conjecture can be made of the maladies of the one and the other: that if words are enough to cure the malady of the People, and that of the Prince needs the sword, there will never be anyone who will not judge that where the greater cure is required, they are where the greater errors exist.