Exclusive 3:16 Interview with Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling

Interview by Richard Marshall

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775–1854) is, along with J.G. Fichte and G.W.F. Hegel, one of the three most influential thinkers in the tradition of ‘German Idealism’. According to Andrew Bowie 'although he is often regarded as a philosophical Proteus who changed his conception so radically and so often that it is hard to attribute one clear philosophical conception to him, Schelling was in fact often an impressively rigorous logical thinker. In the era during which Schelling was writing, so much was changing in philosophy that a stable, fixed point of view was as likely to lead to a failure to grasp important new developments as it was to lead to a defensible philosophical system. Schelling’s continuing importance today relates mainly to three aspects of his work. The first is his Naturphilosophie, which, although its empirical claims are largely indefensible, opens up the possibility of a modern hermeneutic view of nature that does not restrict nature’s significance to what can be established about it in scientific terms. The second is his anti-Cartesian account of subjectivity, which prefigures some of the most influential ideas of thinkers like Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Jacques Lacan, in showing how the thinking subject cannot be fully transparent to itself. The third is his later critique of Hegelian Idealism, which influenced Kierkegaard, Marx, Nietzsche, Heidegger.'

3:16: What made you a philosopher?

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling: Those who want to find themselves at the starting point of a truly free philosophy, have to depart even from God. Here the motto is: whoever wants to preserve it will lose it, and whoever abandons it will find it. Only those have reached the ground in themselves and have become aware of the depths of life, who have at one time abandoned everything and have themselves been abandoned by everything, for whom everything has been lost, and who have found themselves alone, face-to-face with the infinite: a decisive step which Plato compared with death. That which Dante saw written on the door of the inferno must be written in a different sense also at the entrance to philosophy: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’

3:16: It sounds a very demanding activity Friedrich, almost a kind of existential choice?

FS: Those who look for true philosophy must be bereft of all hope, all desire, all longing. They must not wish anything, not know anything, must feel completely bare and impoverished, must give everything away in order to gain everything. It is a grim step to take, it is grim to have to depart from the final shore.

3:16: Wow. Heavy. Do you think all philosophers should do things your way?

FS: Richard I want you to please note: I never wished through the founding of a sect to take away from others and least of all from himself the freedom of investigation in which he has declared himself still engaged and will probably will always declare himself engaged. In the future he will also maintain the course that he has taken where, even if the external form of dialogue is lacking, everything arises as a sort of dialogue. Many things could have been more sharply defined and treated less casually, many protected more explicitly from misinterpretation. I have refrained from doing so partly on purpose.

3:16: So you don’t mind if people disagree with your thinking?

FS: Whoever will and cannot accept what I say should accept nothing at all and seek other sources.

3:16: Very cool. Is Kant’s transcendental idealism the kicking off point for your thinking? Basically, is your issue the question of how presentations of the mind connect with reality?

FS: Well Richard, let’s face it, If there is to be any philosophy at all, this must be resolved – and the solution of this problem, or answer to the question: ‘how can we think both of presentations as conforming to objects, and objects as conforming to presentations?’ is, not the first, but the highest task of transcendental philosophy.

3:16: How should we do this? Wasn’t Kant’s solution any good?

FS: How both the objective world accommodates to presentations in us, and presentations in us to the objective world, is unintelligible unless between the two worlds, the ideal and the real, there exists a pre-determined harmony. But this latter is itself unthinkable unless the activity whereby the objective world is produced, is at bottom identical with that which expresses itself in volition, and vice versa.

3:16: So what’s your proposal?

FS: Nature is visible Spirit, and Spirit is invisible Nature.

3:16: This is kind of what Fichte and Spinoza suggests isn’t it – that the essence of nature produces the subjectivity that enables it to understand itself - it’s the super subject that the Matrix’s blue pill creates isn’t it?

FS: I ask: how is it that the absolute ‘I’ goes out of itself and opposes a ‘Not-I’ to itself? Nothing can be posited by itself as a thing. That is, an absolute/unconditioned thing is a contradiction. So how is it that I step at all out of the absolute and move towards something opposed?

3:16: So you’re wanting to escape the fatalist idealism of Spinoza (who saw everything as the necessary workings of God) but also want to avoid being left with just the formal rule-organized objective idea of nature as found by the natural sciences. Is that it Friedrich?

FS: Think of nature as productivity Richard. As the object - qua ‘conditioned condition’ - is never absolute/unconditioned then something per se non-objective must be posited in nature; this absolutely non-objective postulate is precisely the original productivity of nature.

3:16: So things in themselves appear as products, a bit like in the Matrix where intelligent, conscious beings like us could spend most or all of their lives in a shared virtual reality, acting upon empirical objects laid out in an immersive spatial environment, possibly not realizing that they have biological brains that aren’t part of the same spatial manifold?

FS: I did like that movie Richard. Keanu Reeves’s acting style captures the essence of my own philosophy I think. So yes, to answer your question, things in themselves are productivity inhibiting themselves.

3:16: How do they do this?

FS: Through the principle of all explanation of nature - universal duality.

3:16: So the Kantian dualism breaks down because what - you think things in themselves and their representations can’t be absolutely different because we know a world that’s both independent of our will and yet can be affected by our will?

FS: Yes. One can push as many transitory materials as one wants, which become finer and finer, between mind and matter, but sometime the point must come where mind and matter are One, or where the great leap that we so long wished to avoid becomes inevitable.

3:16: You’ve got to somehow put the subject and object together though haven’t you or else you get another dualism no better than Kant’s? If nature is an absolute producing subject making both objective nature as its predicates plus the spontaneous thinking subject needed for the synthesis constitutive of objectivity, how do these two subjects relate to each other?

FS: Through the fact that the practical act of the absolute ‘I’ via which all limitation is posited as the condition of all consciousness does not itself come to consciousness.

3:16: So thought comes from unconscious forces, an historically unfolding process of the absolute, as you might put it? What's all this talk about absolutes about Friedrich?

FS: The absolute refers to an absolute unity, something higher constituting the ground of identity between the absolutely subjective and the absolutely objective, the conscious and the unconscious. It can be neither subject nor object and also not both at once, but only the absolute identity in which there is no duplicity at all.

3:16: And what's all this stuff about ground and existence? You've got to admit you can be a bit obscure Friedrich.

FS: The primary distinction between ground and existence, the common point of contrast for both is a being before all ground and before all that exists ,before any duality . It cannot be described as the identity of opposites; it can only be described as the absolute indifference of both.

3:16: So it stands outside any relations at all. How can we access it then?

FS: How is it that I step at all out of the absolute and move towards something opposed? Intellectual intuition.

3:16: So what is this intuition?

FS: Intellectual intuition presupposes a capacity simultaneously to produce and intuit certain actions of mind, so that the object and the intuition itself are absolutely one . But this intellectual intuition is itself an absolutely free act, this intuition cannot therefore be demonstrated, it can only be demanded.

3:16: What’s the reason for this distinction between being as ground and being as existence?

FS: Not quite right Richard. The highest point of the entire investigation is: What end should serve this primary distinction between being, in so far as it is ground, and in so far as it exists?

3:16: Ok. So what’s the answer?

FS: The being or essence of the ground, as that which exists, can only be that which comes before all ground, thus the absolute considered merely in itself, the non-ground . But as proved it cannot be this in any other way than insofar as it divides into two equally eternal beginnings, not that it can be both at once, but that it is in each in the same way, thus in each the whole, or its own being.

3:16: And you bring love in here don't you, which seems very groovy. What’s love got to do with all this?

FS: Hold on Richard. Let me explain. The non-ground divides itself into the two exactly equal beginnings, only so that the two which could exist simultaneously or be one in it as the non-ground, become one through love, that is, it divides itself only so that there may be life and love and personal existence.

3:16: How does love do this? I mean, what powers has it got? What is love for you Friedrich because I have to say it seems way more complicated than I took it to be?

FS: Richard, love is neither in indifference nor where opposites are linked which require linkage for their Being as in Hegel’s dialectic but rather , and this is the secret of love, that it links such things which could each exist for itself, yet does not and cannot exist without the other.

3:16: See what I mean? - that’s complicated.

FS: Let me put it simply for you Richard. We have, then, one being for all oppositions, an absolute identity of light and darkness, good and evil.

3:16: You should have said that at the start and left it at that. Ok, let's move on. You broke with the model of truth as correspondence didn't you? Why ?

FS: It is clear that in every explanation of the truth as a correspondence of subjectivity and objectivity in knowledge, both, subject and object are already presupposed as separate, for only what is different can agree, what is not different is in itself one.

3:16: Is it a version of Spinoza’s monism that you’re proposing?

FS: No! Most people see in the essence of the Absolute nothing but pure night and cannot recognise anything in it; it shrinks before them into a mere negation of difference, and is for them something purely privative, whence they cleverly make it into the end of their philosophy. I want to show here how that night of the Absolute can be turned into day for knowledge.

3:16: Ok, stay cool Friedrich. How do you do that?

FS: Think of Hölderlin’s notion of the transitive being in terms of a metaphor of the earth. You recognise the earth’s true essence only in the link by which it eternally posits its unity as the multiplicity of its things and again posits this multiplicity as its unity. You also do not imagine that, apart from this infinity of things which are in it, there is another earth which is the unity of these things, rather the same which is the multiplicity is also unity, and what the unity is, is also the multiplicity, and this necessary and indissoluble One of unity and multiplicity in it is what you call its existence . Existence is the link of a being as One, with itself as a multiplicity.

3:16: A little obscure again here Friedrich! Ok, are you saying that absolute identity links two aspects of being: the universe plus the changing multiplicity which the known universe is?

FS: Yes Richard, a philosophy which starts with consciousness - in the sense of the separation of subject and object - will therefore never be able to explain that correspondence, neither is it to be explained without original identity, whose principle necessarily lies beyond consciousness.

3:16: Are you taking issue with the whole philosophical project that started with Descartes?

FS: Too right I am. The ‘I think, I am’, is, since Descartes, the basic mistake of all knowledge; thinking is not my thinking, and being is not my being, for everything is only of God or the totality. Thus, for example, time is itself nothing but the totality appearing in opposition to the particular life of things, so the totality posits or intuits itself, by not positing, not intuiting the particular. For being, actual, real being is precisely self-disclosure/revelation.

3:16: Ok Friedrich, you're getting a bit tricky to follow again. Let's try once more - How do we get from being to 'I'?

FS: (sighs) Ok Richard. Try this. If it is to be as One then it must disclose/reveal itself in itself; but it does not disclose/reveal itself in itself if it is not an other in itself, and is in this other the One for itself, thus if it is not absolutely the living link of itself and an other. Nothing, though, prevented one going back with this “I” which is now conscious within me to a moment where it was not yet conscious of itself, – nothing prevented one assuming a region beyond my now present consciousness and an activity which does not itself come but rather only comes via its result into consciousness.

3:16: So being conscous has to involve something we're not conscious of, is that it?

FS: See, you can do this Richard if you try! Coming to consciousness and being limited is one and the same the limiting activity falling outside all consciousness. Limitation must appear as independent of me because I can only look at my being-limited, never the activity by which it is posited. The activity by which the objective world is produced’ should be originally identical with that which expresses itself in willing, and vice versa. Having arrived, then, at the “I am”, with which its individual life begins, the I no longer remembers the path which it has covered so far, for as it is only the end of this path which is consciousness, the now individual I has covered the path unconsciously and without knowing it.

3:16: Doesn't that mean we can’t ever know what we are?

FS: Richard, The subject can never grasp itself as what it Is, for precisely in attracting itself , which has the sense of ‘putting on’ what one is it becomes an other, this is the basic contradiction, we can say the misfortune in all being. A schema for myself is not an idea that is determined on all sides, but an intuition of the rule according to which a particular object can be produced.

3:16: What’s the difference between us and other natural organisms, or are we just like the rest of nature?

FS: Every plant is completely what it should be, what is free in it is necessary and what is necessary is free. On the other hand Man is eternally a fragment because when we consciously think the I is to become aware of itself as producing unconsciously. This is impossible and only for this reason does the world appear to it as present without its action as a thing in itself. What that self-determination is, nobody can explain who does not know it via their own intuition.

3:16: So what’s real and what’s ideal?

FS: Real and ideal are only different views of one and the same substance.

3:16: Is it like in the Matrix, as we said earlier, where both worlds are real?

FS: Reflection only knows the universal and the particular as two relative negations, the universal as relative negation of the particular, which is, as such, without reality, the particular, on the other hand, as a relative negation of the universal. Something independent of the concept must be added to posit the substance as such.

3:16: So unlike in Fichte, where subject and object are just negations of each other and locked in a vicious circle, you break out from that?

FS: Yes, in Fichte nothing gains reality by the relation to another nothing. Mine is a negative philosophy, but much has already been gained by the fact that the negative, the realm of nothingness, has been separated by a sharp limit from the realm of reality and of what alone is positive. Mine is a system of absolute identity that completely removes itself from the standpoint of reflection since the latter presupposes nothing but oppositions and rests on oppositions.

3:16: As we said earlier, one of the big worries for you is to avoid Spinoza’s neccesitarianism, his notion that we’re all fated, because you think we need a notion of freedom to make sense of our ethical choices and responsibilities – is this why you introduce the Kantian idea of ‘willing’?

FS: In the last and highest instance there is no other being but willing. Willing is primal being, and all the predicates of primal being only fit willing: groundlessness, eternity, being independent of time, self-affirmation.

3:16: So you have here an uncaused ground which helps you avoid Spinoza’s determinism. But mustn’t you also have a non-free being, something against which freedom can be manifested and meaningful?

FS: Poured from the source of things and the same as the source, the human soul has a co-knowledge/con-science of creation. We have two principles within: an unconscious, dark principle and a conscious principle.

3:16: Is this how you make sense of your discussion of good and evil when discussing freedom?

FS: It does Richard. We have seen how, through false imagining and cognition that orients itself according to what does not have Being, the human spirit opens itself to the spirit of lies and falsehood, and, fascinated by the latter, soon loses its initial freedom. It follows from this that, by contrast, the true good could be effected only through a divine magic, namely through the immediate presence of what has Being in consciousness and cognition. An arbitrary good is as impossible as an arbitrary evil.

3:16: This makes evil a structure of a course of action rather than a name for the property of an action yes?

FS: Yes.

3:16: And good is about openness for rational theory change?

FS: Yes.

3:16: And does this same structure apply to God?

FS: The ‘real’, which takes the form of material nature, is ‘in God’ but is not God seen absolutely, that is, insofar as He exists; for it is only the ground of His existence, it is nature in God; an essence which is inseparable from God, but different from Him. God is a predicative being which flows out, spreads, gives itself.

3:16: There seems to be a contradiction inherent in this sort of Being doesn’t there?

FS: Properly understood, the law of contradiction really only says that the same cannot be as the same something and also the opposite thereof, but this does not prevent the same, which is A, being able, as an other, to be not A.

3:16: Is this like saying that if we’re conscious virtual reality beings in a computer simulation we’re both people and also just computer algorithms? Dynamic processes are the result of the interchange between these ultimately identical forces?

FS: That sounds about right.

3:16: Is this a unity that is always changing, in play, transitory – there’s no reconciliation to finite existence?

FS: Yes, hence the veil of melancholy which is spread over the whole of nature, the deep indestructible melancholy of all life. Everything finite goes to ground.

3:16: So Spinoza is done with here because of course there’s no freedom in Spinoza’s system.

FS: The higher, the genuine opposition, is of freedom and necessity. With this the innermost center-point of philosophy first comes into consideration. Without the contradiction of necessity and freedom not only philosophy but each higher willing of the spirit would sink into the death that is proper to those sciences in which the contradiction has no application.

3:16: Does this process give us a historical sense of ‘ages of the world’ as this constant process? You think language emerges from this don’t you?

FS: The ultimate truth maker is the unprethinkable being. It is necessary to inspect the history of self-consciousness as we move from unconsciousness to consciousness. It seems universal that every creature which cannot contain itself or draw itself together in its own fullness, draws itself together outside itself, whence for example the elevated miracle of the formation of the word in the mouth belongs, which is a true creation of the full inside when it can no longer remain in itself. The world is the original, yet unconscious poetry of the mind.

3:16: Listening to you it strikes me that you seem to have problems throughout with the principle of identity - one that supposes that A = A - which has always struck me as a principle that’s obviously to the point of banality true. Why doesn’t it strike you in the same way?

FS: Oh Richard, the principle of identity does not express a unity which, turning itself in the circle of seemless sameness , would not be progressive and, thus, insensate or lifeless. The unity of this law is an immediate creative one.

3:16: And a proposition for you isn’t like Frege’s and Russell’s either is it?. You say the unity of a proposition is irreducible to its constituent parts. Do subject and predicate have a merely formal difference then?

FS: Yes to all that Richard. Take evil. The perfect is the imperfect. The perfect and the imperfect are the same, all is the same in itself, the worst and the best, foolishness and wisdom. The imperfect is not due to that through which it is imperfect but rather through the perfect that is in it.

3:16: Hmm. Sounds a bit tricksy to me Friedrich. What’s language then?

FS: Language is the contracted material signifier. The ideal capacity for expansion prevents language becoming congealed.

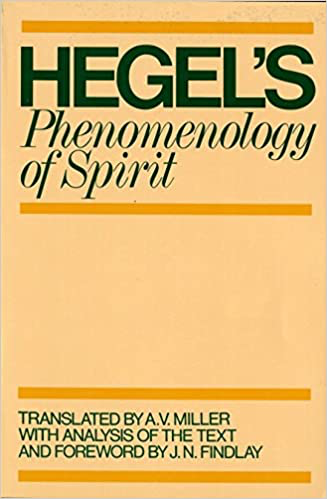

3:16: Now Hegel and Fichte were two of your contemporaries. You fell out with both. You disagreed with Hegel over his approach because he ended up reducing everything to abstractions – in this you’re a bit like Marx I guess?

FS: Hegel failed to see that we live in this determinate world, not in an abstract or universal world that we so enjoy deluding ourselves with by holding fact to be the most universal properties of things, without penetrating to their actual relationships. This comes from the common mistake of every positive philosophy that has existed up to now that asserts a merely logical relationship of God to the world whereby the entailed reflexivity whereby God and the world are the other of themselves.

3:16: For you the particular and the universal are equal in the absolute yes?

FS: That’s my point against Hegel. We say that something lasts because its existence is fully inadequate to its essence, its particular is inadequate to its universal. Duration is nothing but a continuous position of its universal in its concreteness. By virtue of the limited character of the latter, the thing is not of the trio and, de facto, is not all of a sudden what it could be as for its essence or its universal. Now, once again this is unthinkable in the absolute, because in it the particular is absolutely equal to the universal; it is also what it can be, really and at once, without the intromission of time: therefore it is without time and eternal in itself.

3:16: Because you think the identity of thought and being can’t be articulated within thought you think we need a notion of ‘concept’ that is already subject and object don't you?

FS: Yes, because either the concept would have to go first, and being would have to be the consequence of the concept, which would mean it was no longer absolute being; or the concept is the consequence of being, then we must begin with being without the concept.

3:16: And Hegel doesn’t do this? So how do you overcome this problem of reflection?

FS: Our self-consciousness is not at all the consciousness of that nature which has passed through everything, it is precisely just our consciousness, for the consciousness of man is not equal to the consciousness of nature . Far from man and his activity making the world comprehensible, man himself is that which is most incomprehensible. What we call the world, which is so completely contingent both as a whole and in its parts, cannot possibly be the impression of something which has arisen by the necessity of reason. It contains a preponderant mass of unreason.

3:16: Ah, so is this where madness comes in?

FS: Madness is a predecessor of understanding. Understanding is regulated madness.

3:16: So you’re saying that reason evolved to what it is today from something from today’s perspective would seem like madness?

FS: Yes.

3:16: Is this where the importance of art to philosophy comes in? In nature we start unconscious and end in conscious scientific knowledge whilst art goes in the other direction according to you doesn't it?

FS: Indeed it does Richard. Art is the organ of philosophy. In the art work the ‘I’ is conscious according to the production, unconscious with regard to the product. Art is, then, the only true and eternal organ and document of philosophy, which always and continuously documents what philosophy cannot represent externally. Genius is the inborn mental trait through which nature gives the rule to art.

3:16: So art shows what can’t be said?

FS: Yes. The aesthetic intuition is simply the intellectual intuition become objective and nature is a poem that lies enclosed in a secret, wonderful script.

3:16: There’s something Dionysian in your ideas – you sound a bit Nietzschean or Schopenhauerean here?

FS: If Dionysean is formlessness then yes. The idea of something absolutely formless which cannot be represented anywhere as determinate material is nothing but the symbol of nature approaching the productivity. The nearer it is to productivity the nearer it is to formlessness.

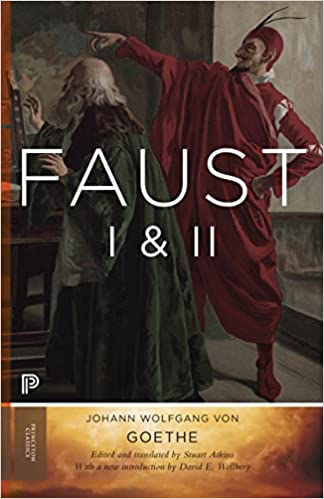

3:16: You’re a friend of Goethe and think his Faust is something you recommend to philosophers don’t you? In fact you think art is the way to get to philosophy don’t you because it can express what philosophy can’t?

FS: All of our knowledge stems from experience but the work of art is the only true and eternal organ and document of philosophy. Goethe’s Faust is nothing else than the most intrinsic, purest essence of our age. And to quote him – ‘The beautiful is a manifestation of secret laws of nature, which without its appearance would have remained forever hidden.’ Aesthetic intuition is intellectual intuition which has become objective. Art always and continually documents anew what philosophy cannot represent externally, namely the unconscious in action and production and its original identity with the conscious.

3:16: So what is a work of art for you?

FS: The sole true and eternal organ and at the same time document of philosophy.

3:16: And what’s the connection between a genius in art - like your friend Goethe – and destiny?

FS: The power, which, via our free activity without our knowledge and even against our will, realises purposes which have not been imagined, is called destiny.

3:16: Art for you requires public not private receptions, which isn’t always easy in modernity is it?

FS: Quite. A nation which has nothing holy cannot have true tragedy. Athenian society was based on public freedom, not the slavery of private life. Beauty is posited where the particular, the real - in the sense of the sensuous particular object - is so appropriate to its concept that the concept, as infinite, enters into the finite and is contemplated in concreto. God’s don’t mean they are in this world. In art the eternal ideas of reason become as objective as the souls of organic bodies. In art each thing should have a particular and free life. Only the understanding subordinates in reason; and in imagination all is free and moves in the same ether, each for itself is also the whole.

3:16: We don’t live like that anymore – and outside of fascism probably can’t. So where do we find these myths - are they maybe hidden in our language, ready for the artistic genius to discover them?

FS: Well yes. Think what treasures of poetry lie hidden in language in itself, which the poet does not put into language, which he, so to speak, only lifts out of it as out of a treasure chamber, which he only persuades language to reveal. But is not every attribution of a name a personification, and if all languages think or expressly designate things which admit an opposition with differences of gender; if the German says der Himmel [sky], die Erde [earth]; der Raum [space], die Zeit [time]: how far is it from there to the expression of spiritual concepts by male and female divinities. One is almost tempted to say: language itself is only faded mythology, in it is preserved in only abstract and formal differences what mythology preserves in still living and concrete differences.

3:16: This sounds a bit like Heidegger’s idea of language as a ‘house of being’ – but then he was an actual fascist!

FS: Very few people reflect upon the fact that even the language in which they express themselves is the most complete work of art.

3:16: Music’s a big thing for you isn’t it?

FS: It is the most closed of all arts. It’s form is succession in time and time is itself nothing but the totality appearing in opposition to the particular life of things. Rhythm is the music in music, the imprinting of unity into multiplicity, the transformation of a succession which is in itself meaningless into a significant one.

3:16: Cosmic! So art reveals the hidden structures of nature. Are you a naturalist?

FS: Of course. It is a vintage delusion Richard to think that organization and life cannot be explained from natural principles. One would at least take one step toward such an explanation if one could show that the stages of all organic beings have been formed through a gradual development of one and the same organization. That our experience has not taught us of any formation of nature, has not shown us any transition from one form or kind into another (although the metamorphosis of many insects could be introduced as an analogous phenomenon) – this is no demonstration against the possibility. For a defender of the idea of development could answer that the alteration to which the organic as well as the inorganic nature was subjected occurred over a much longer time than our small periods could provide measure.

3:16: So were you - and Goethe - thinking in terms of evolutionary theories when it came to biology?

FS: Several naturalists seem to have harboured the hope of being able to represent the source of all organization as a successive and gradual development of one and the same original organization. This hope, in our view has vanished. The belief that the different organizations are really formed through a gradual development out of one another is a misunderstanding of an idea that really lies in reason.

3:16: Hmm. That doesn’t sound right! Which naturalists are you thinking of?

FS: Erasmus Darwin.

3:16: Ah, now he was a Lamarckian wasn’t he? What do you propose instead?

FS: An archetype that would be the absolute, the sexless condition that is neither the individual nor the species, but both together, in which the individual and the species are conjoined. This absolute organization cannot be represented through a particular product, but only through an infinity of particular products, which particulars deviate from the ideal in infinite ways, but in the aggregate are congruent with the ideal.

3:16: And you think, along with Goethe, that this ideal would be realized through the temporal development of a huge variety of types responding to natural forces don’t you? So you’re actually proposing a different evolutionary model, not throwing out evolutionary theories?

FS: Yes. The metamorphosis of plants, according to Goethe’s theory, has proved indispensable to me as the fundamental scheme for the origin of all organic beings. By his work, I have been brought very near to the inner identity of all organized beings among themselves and with the earth, which is their common source. That earth can become plants and animals and was indeed already in it through the establishment of the dynamic basic organization, and so the organic never indeed arises, since it was already there. This was Goethe’s answer to Kant’s objection that organic life cannot arise out of inorganic earth. In the future we will be able to show the first origin of the more highly organized plants and animals out of the mere dynamically organized earth, just as you were able to show how the more highly organized blooms and sexual parts of plants could come from the initially more lowly organized seed leaves through transformation.

3:16: So let me get this straight - you agree with Goethe - the artist/biologist Carus agreed with Goethe - Carus was brought over to England by Richard Owen - he shared it with Charles Darwin and Charles Darwin historicized the theory. So in a way then, you prefigured Darwin’s theory of evolution. Awesome Friedrich! Interestingly, it was you that moved Goethe to a more idealistic view, which helped foster his incipient evolutionary ideas wasn’t it, via helping him develop his notion of the world soul?

FS: If you say so Richard. One and the same principle joins inorganic and organic nature so that: Not: where there is no mechanism, there is organism; but the reverse: where there is no organism, there is mechanism.

3:16: So you’re not a vitalist – you don’t think there’s a life force?

FS: Nature, in its blind lawfulness, must be free, and conversely, in its complete freedom, it must be lawful; only in thus uniting the two do we find the concept of organization.

3:16: Is the origin of the concept of organic life contingent?

FS: Whatever it is that puts the forces into play that give rise to life must indeed be some spatial principle that removes organic nature from the sphere of the universal forces of nature, elevating what would otherwise have the dead product of formative forces into the higher sphere of life. Only by regarding it thus do we see the origin of all organic beings to be contingent, as required by the concept of the organic. Only to the extent that the organic is the product of nature’s freedom – the product, that is, of nature’s free play – can it arouse ideas of purposiveness , and only to the extent that it arouses such ideas, is it organic.

3:16: Does this link with your theory of world history? After all, don’t you say that nature is unconsciously purposive regularity?

FS: Well, to say that necessity is again to be present in freedom amounts to saying that through freedom itself something I do not intend is to come about unconsciously, that is, without my consent; the conscious , or that freely determining activity is to be confronted with an unconscious whereby, out of the most uninhibited expression of freedom, there arouses something wholly involuntary and perhaps even contrary to the agent’s will, which he himself could never have realized through his willing. But I also say that unconscious activity is originally identical with and sprung from the same root as the conscious.

3:16: Right. So this is the realm of free spontaneity, of play, of playfulness?

FS: To speak of a history of nature in the true sense of the word we should have to picture nature as though apparently free in its own productions, it had gradually brought forth the whole multiplicity of its productions – as I said earlier – through constant departures from a primordial original; which would then be a history, not of natural objects but of generative nature itself. In a history of sort we should thus regard her as acting freely in this creation but not on that account as working in utter lawlessness.

3:16: From this perspective do blind necessity and rational self-determination converge?

FS: Yep.

3:16: We mentioned Goethe’s Faust earlier. One of the things you took from it was how the contemplation of the infinite was a tragic thing?

FS: The subject as subject cannot enjoy the infinite as infinite. It is nevertheless a necessary inclination and therein lies the tragedy. The completed forms of the gods can only first appear after what is formless, dark and monstrous has been repressed. Just as in earlier times, poetry preceded philosophy – to which especially Goethe had a truly prophetic relation – so now a revitalized philosophy is determined to bring about a new age of poetry. The advance of science must not come at too high a cost. I see a time coming when God will no longer have any pleasure in humanity; he will once more have to destroy everything to make room for a renewed creation.

3:16: Deep Friedrich. Is this because you think science has rendered religion unsatisfactory and we haven’t found new myths for our modern age?

JS: In this general dissolution there will be for a time nothing that is secure, to which one can rely, and on which one can build: the beautiful illusions that made past ages happy have vanished in the face of merciless truth. Truth, pure truth it is, which one demands in all relations of life and which is the only thing one still wants, so that one can only rejoice if a time has come in which war is openly declared on every lie, every deception, where it is proclaimed as a principle that truth is something to be desired at any price, even the most painful.

3:16: So the truth brings despair? This all sounds pretty Nietzschean.

FS: The vanity of all human attempts to gain highest knowledge which began great ended small. We ask: why is there anything at all? Why is there not simply nothing? Ever-progressing science has long since undermined answers based on God. This is the melancholy of nature.

3:16: How do you answer this despair?

FS: The first challenge for one who demands to be led into philosophy is to rise above and beyond any being that is present and already in existence. A person should be thrifty with nothing more than with one’s capacity, for in it is true force and strength to refrain from using it builds a treasure one will never lose. Understand that all of those concepts that determine being as actual presence have no applicability to the source of being. The ground of being is sinister.

3:16: You tell the story in mythical terms: the primordeal capacity to be is willing and lusting and embodied in Cronos. Cronos excercises his capacities and overplays his power and gets chucked into the underworld. Is what puts him there a self-surrender that comes with the very act of activating his will and lust?

FS: Yes, the primordial is freed and redeemed through this new relationship from its particularity, that is to say, from its selfhood.

3:16: Which all sounds a bit naturalistic – you discuss all this in the same breath as when you’re talking about the anatomy of plants and the poems you wrote with Goethe don’t you?

FS: Anyone who knows the joys of comparative anatomy should be enthused by the words that follow. ‘You lead the procession of living beings/Before me, teaching me to recognize my brothers/Amidst quiet bushes and in air and water’ – with the culmination, ‘ You then show me myself/Letting the deep miraculous secrets /of my own breast reveal themselves to me.’

3:16: It’s also got a Protestant feel too – a fall from grace myth-structure perhaps? Mere givenness makes nature open to scientific investigation, from which you work out the nature of nature itself- which is also another idea of the ancients?

FS: The essence of things that is dissolved in God, that is, the essence of the particular insofar as it is immediately being and therefore infinite self-positing, is called ‘idea’ by the ancients. The idea can also be considered the copula or the natura naturans in all things. The quality of each thing is a feeling of nature in things. As I keep telling you Richard, things therefore have a fully immediate and eternal essence according to the idea; the foundation of every single being, precisely insofar as it is single, lies in the eternal copula.

3:16: We’re back in Matrix territory again then.

FS: Yes , where the affirming - or concept - and the affirmed are therefore joined in an eternal and necessary manner, so that, prescinding from the latter, the former might be as little real and effective as the latter if separated from the former. The affirming taken by abstracting from the affirmed or in contradiction with it is the principle of time. If, however, it is not seen from the standpoint of contradiction but from that of unity or the copula inherent in contradiction , then eternity is recognized in things. The principle of time is manifested according to an abstract understanding as what is always the centre but never a circumference or a bond, because it overshadows the affirmed. But in real unity (in the absolute copula) the affirming is joined with the affirmed not in a temporal and provisional way, but according to an eternal modality independent from time.

3:16: So does it follow from this that if we just focus on scientific objectification we get, in your terms, just the melancholy of nature, and the emptiness of modernity?

FS: Through its name the old metaphysics declared itself to be a science that followed in accordance with, and that to some extent also followed from, our knowledge of nature and improved and progressed from that; thus in a certain competent and sound way that is of service only to those who have a desire for knowledge, metaphysics took the knowledge that it boasted in addition to physics. Modern philosophy did away with its immediate reference to nature, or didn’t think to keep it, and proudly scorned any connection to physics. Continuing with its claims to the higher world, it was no longer metaphysics but hyperphysics.

3:16: So is nature purposeful? Is it to be understood in terms of teleology? That's a big no no these days Friedrich I have to say.

FS: It is purposeful without being explicable in terms of purposes.

3:16: Sounds a bit like Kant’s approach to beauty - you know – all that purpose without a purpose jazz? Always strikes me as a bit of a con. Are you saying you think philosophy has to wake up to this?

FS: The whole of modern European philosophy has this common deficiency – that nature does not exist for it.

3:16: You’re talking about Hegel and Fichte here I guess.

FS: Yes. In them the fact or the feeling of freedom is immediately imprinted on every individual at the expense of a realist account of nature, as we’ve discussed. I am thoroughly aware of how small an area of consciousness nature must fall into, according to Fichte’s conception of it. For him nature has no speculative significance, only a teleological one. Fichte is really of the opinion that light is only there so that rational beings can also see each other when they talk to each other, and that air is there so that when they hear each other they can talk to each other. Idiotic, Richard, idiotic.

3:16: So we’re back with the dialectic between the individual and the general again?

FS: Nature contests the Individual; it longs for the Absolute and continually endeavors to represent it. It seeks the most universal proportion in which all, without prejudice to their individuality, can be unified. Individual products, therefore, in which Nature’s activity is at a standstill, can only be seen as misbegotten attempts to achieve such a proportion. In the last analysis what is the essence of Fichte’s whole opinion of nature? It is this: that nature should be used and that it is there for nothing more than to be used; his principle, according to which he looks at nature, is the economic-teleological principle.

3:16: And of course you’re against pantheism, the assumption that there’s a prearranged, determined order to nature, as in Spinoza?

FS: Of course. Nature’s goal, like I keep saying Richard, is becoming completely objective to itself in reason, through which nature first completely returns into itself, and through which it becomes manifest that nature is originally identical with what is known in us as intelligent and conscious.

3:16: This sounds like a version of panpsychism, you know, where Nature is a subjective process?

FS: As the object is never absolute then something per se non-objective must be posited in nature; this absolutely non-objective postulate is precisely the original productivity of nature.

3:16: So freedom is a naturally necessary act rather than a free moral act?

FS: The egotism of each individual act must join itself to that of all the others; what is produced is a product of the subordination of all under one and one under all, i.e., the most complete mutual subordination. No individual potency could produce the whole for itself, but all together can produce it. The product does not lie in the individual, but in all together. We must not look for an origin in time of a moral character. If in a different turn of phrase, necessary and free things are explained as One, the meaning is that the same thing (in the final judgment) which is the essence of the moral world is also the essence of nature.

3:16: Sometimes you sound as if your metaphysical programme doesn’t quite succeed in getting to where you want it to go. Is that fair Friedrich?

FS: Well Richard, let’s face it; our self-consciousness is not at all the consciousness of that nature which has passed through everything, it is precisely just our consciousness. For the consciousness of man is not the consciousness of nature . Far from man and his activity making the world comprehensible, man himself is that which is most incomprehensible. Go figure.

3:16: And are there five books you can recommend to us that will take us further intoyour philosphical world?

FS: Sure.

Kant's Critique of Pure Reason

Fichte The Science of Knowing

Goethe Faust

Hegel Phenomenology of Spirit

Holderlin Poems

About the Author

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.