Exclusive 3:16 Interview with Arthur Schopenhauer

Interview by Richard Marshall

[ Pic: 3:16 post-lockdown party from which the idea of a series of postumous philosophy interviews was conceived over wine and jokes ]

Born in Danzig (Gdansk) in 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer was brought up in Hamburg, the son of a cosmopolitan businessman and a literary mother. Independently wealthy, he never held a paid academic post, and had indeed nothing but scorn for those who live “from rather than for philosophy”, namely, “the professors of philosophy”. Independence of means, Schopenhauer insists, is a prerequisite of independence of thought. Accompanied by a succession of poodles, he has never married, and lives in Frankfurt. On the wall of his study he has a portrait of Kant and, on his desk, a statue of the Buddha. For pleasure, he reads The Times of London, plays the flute, and attends the Frankfurt opera.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Arthur Schopenhauer: Life is an unpleasant business. I have resolved to spend mine reflecting on it. How very paltry and limited the normal human intellect is, and how little lucidity there is in the human consciousness, may be judged from the fact that, despite the ephemeral brevity of human life, the uncertainty of our existence and the countless enigmas which press upon us from all sides, everyone does not continually and ceaselessly philosophize, but that only the rarest of exceptions do. Philosophy ... is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions. A poet or philosopher should have no fault to find with his age if it only permits him to do his work undisturbed in his own corner; nor with his fate if the corner granted him allows of his following his vocation without having to think about other people.

3:16: You’ve a pessimistic take on the world don’t you?

AS: There is not much to be got anywhere in the world. It is filled with misery and pain; if a man escapes these, boredeom lies in wait for him at every corner. Nay more; it is evil which generally has the upper hand, and folly that makes the most noise. Fate is cruel and mankind pitiable. The vanity of existence is revealed in the whole form existence assumes: in the infiniteness of time and space contrasted with the finiteness of the individual in both; in the fleeting present as the sole form in which actuality exists; in the contingency and relativity of all things; in continual becoming without being; in continual desire without satisfaction; in the continual frustration of striving of which life consists. . . Time is that by virtue of which everything becomes nothingness in our hands and loses all real value. The world is Hell, and men are on the one hand the tormented souls and on the other the devils in it.

3:16: So pain outweighs pleasure?

AS: Oh indeed! A quick test of the assertion that enjoyment outweighs pain in this world, or that they are at any rate balanced, would be to compare the feelings of an animal engaged in eating another with those of the animal being eaten.

3:16: Some of us manage to keep a sense of humour, even a sense of optimism despite this. Don’t you think that facing this truth is too pessimistic and that we need to be optimistic and acknowledge the positives of the world? Don't we need hope?

AS: You're an idiot. Hope is the confusion of the desire for a thing with its probability. My God man, think about it: to this world, to this scene of tormented and agonised beings, who only continue to exist by devouring each other, in which, therefore, every ravenous beast is the living grave of thousands of others, and its self-maintenance is a chain of painful deaths; and in which the capacity for feeling pain increases with knowledge, and therefore reaches its highest degree in man, a degree which is the higher the more intelligent the man is; to this world it has been sought to apply the system of optimism, and demonstrate to us that it is the best of all possible worlds. The absurdity is glaring. Optimism is not only a false but also a pernicious doctrine, for it presents life as a desirable state and man's happiness as its aim and object. Starting from this, everyone then believes he has the most legitimate claim to happiness and enjoyment. If, as usually happens, these do not fall to his lot, he believes that he suffers an injustice, in fact that he misses the whole point of his existence. Optimism, where it is not just the thoughtless talk of someone with only words in his flat head, strikes me as not only absurd, but even a truly wicked way of thinking, a bitter mockery of the unspeakable sufferings of humanity.

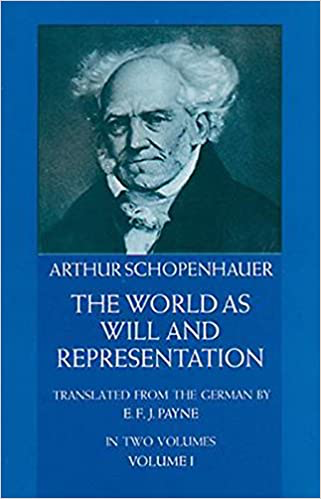

3:16: Doesn't theism give reasons to reject this ?

AS: But it is common knowledge that religions don’t want conviction, on the basis of reasons, but faith, on the basis of revelation. And the capacity for faith is at its strongest in childhood: which is why religions apply themselves before all else to getting these tender years into their possession. It is in this way, even more than by threats and stories of miracles, that the doctrines of faith strike roots: for if, in earliest childhood, a man has certain principles and doctrines repeatedly recited to him with abnormal solemnity and with an air of supreme earnestness such as he has never before beheld, and at the same time the possibility of doubt is never so much as touched on, or if it is only in order to describe it as the first step towards eternal perdition, then the impression produced will be so profound that in almost every case the man will be almost incapable of doubting this doctrine as of doubting his own existence, so that hardly one in a thousand will then possess the firmness of mind seriously and honestly to ask himself: is this true?

3:16: Nevertheless, even if not true, doesn’t religion have worth in a world such as the one you take us to be living in?

AS: Well, firstly, there is no absurdity so palpable but that it may be firmly planted in the human head if you only begin to inculcate it before the age of five, by constantly repeating it with an air of great solemnity. Secondly, let us see rather that like Janus—or better, like Yama, the Brahmin god of death—religion has two faces, one very friendly, one very gloomy. So if you have to live amongst men, you must allow everyone the right to exist in accordance with the character he has, whatever it turns out to be: and all you should strive to do is to make use of this character in such a way as its kind and nature permit, rather than to hope for any alteration in it, or to condemn it off-hand for what it is. This is the true sense of the maxim--Live and let live.

That, however, is a task which is as difficult in proportion as it is right; and he is a happy man who can once and for all avoid having to do with a great many of his fellow creatures. And If God made this world, then I would not want to be the God. It is so full of misery and distress that it breaks my heart.

3:16: So you couldn’t worship any God who made this world because it’s just too bad a place to live in?

AS: There are two things which make it impossible to believe that this world is the successful work of an all-wise, all-good, and, at the same time, all-powerful Being; firstly, the misery which abounds in it everywhere; and secondly, the obvious imperfection of its highest product, man, who is a burlesque of what he should be. Brahma is said to have produced the world by a kind of fall or mistake; and in order to atone for his folly, he is bound to remain in it himself until he works out his redemption. As an account of the origin of things, that is admirable!

3:16: Does following a God always end up being a bad thing?

AS: God, who in the beginning was the creator, appears in the end as revenger and rewarder. Deference to such a God admittedly can produce virtuous actions; however, because fear of punishment or hope for reward are their motive, these actions will not be purely moral; on the contrary, the inner essence of such virtue will amount to prudent and carefully calculating egoism.

3:16: So do you think religion is generally harmful?

AS: Throughout the entire Christian era theism has lain like an incubus on all intellectual, especially philosophical, endeavor and has prevented or stunted all progress; and when anyone has possessed the rare elasticity of mind which alone can slip free of these fetters, his writings have been burned and sometimes their author with them, as happened to Bruno and Vanini. The bad thing about all religions is that, instead of being able to confess their allegorical nature, they have to conceal it; accordingly, they parade their doctrines in all seriousness as true sensu proprio, and as absurdities form an essential part of these doctrines as a result of which we have the great mischief of a continual fraud.

3:16: Your pessimism survives the death of God though doesn't it: you say evil and suffering impugnes the value of existence itself?

AS: Of course.

3:16: Is Spinoza's pantheism attractive to you?

3:16: Spinoza – and Giodano Bruno - they do not belong either to their age or to their part of the globe, which rewarded the one with death, and the other with persecution and ignominy. Their miserable existence and death in this Western world are like that of a tropical plant in Europe. The banks of the Ganges were their spiritual home; there they would have led a peaceful and honoured life among men of like mind. Now, it is true that I have that “one and all” in common with the Pantheists but not their “all is god” ... they are thus put in the position of having to sophisticate away the colossal evils of the world. The origin of wickedness is the cliff upon which pantheism, just as much as theism, is wrecked; for both imply optimism. However, evil and sin, both in their terrible magnitude, cannot be disavowed; indeed, because of the promised punishments for the latter, the former is only further increased. Whence all this, in a world that is either itself a God or the well-intentioned work of a God?

3:16: Hegel’s back in vogue at the moment – in Pittsburg and elsewhere – MacDowell and Brandom seriously and Zizek as an exotic populist version, so what’s wrong with Hegel?

AS: Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel are in my opinion not philosophers; for they lack the first requirement of a philosopher, namely a seriousness and honesty of inquiry. They are merely sophists who wanted to appear to be rather than to be something. They sought not truth, but their own interest and advancement in the world. Appointments from governments, fees and royalties from students and publishers, and, as a means to this end, the greatest possible show and sensation in their sham philosophy-such were the guiding stars and inspiring genii of those disciples of wisdom. And so they have not passed the entrance examination and cannot be admitted into the venerable company of thinkers for the human race.

3:16:You write very clearly - especially for a German philosopher whose contemporaries seem to aim for the opposite. Is it their obscurity that annoys you?

AS: The public had been forced to see by Kant's writings that what is obscure is not always without meaning; what was senseless and without meaning at once took refuge in obscure exposition and language. Fichte was the first to grasp and make vigorous use of this privilege; Schelling at least equalled him in this, and a host of hungry scribblers without intellect or honesty soon surpassed them both. But the greatest effrontery in serving up sheer nonsense, in scrabbling together senseless and maddening webs of words, such as had previously been heard only in madhouses, finally appeared in Hegel. It became the instrument of the most ponderous and general mystification that has ever existed, with a result that will seem incredible to posterity, and be a lasting monument of German stupidity.The so-called philosophy of this fellow Hegel is a colossal piece of mystification which will yet provide posterity with an inexhaustible theme for laughter at our times, that it is a pseudo-philosophy paralyzing all mental powers, stifling all real thinking, and, by the most outrageous misuse of language, putting in its place the hollowest, most senseless, thoughtless, and, as is confirmed by its success, most stupefying verbiage. Hegel, installed from above, by the powers that be, as the certified Great Philosopher, was a flat-headed, insipid, nauseating, illiterate charlatan who reached the pinnacle of audacity in scribbling together and dishing up the craziest mystifying nonsense.

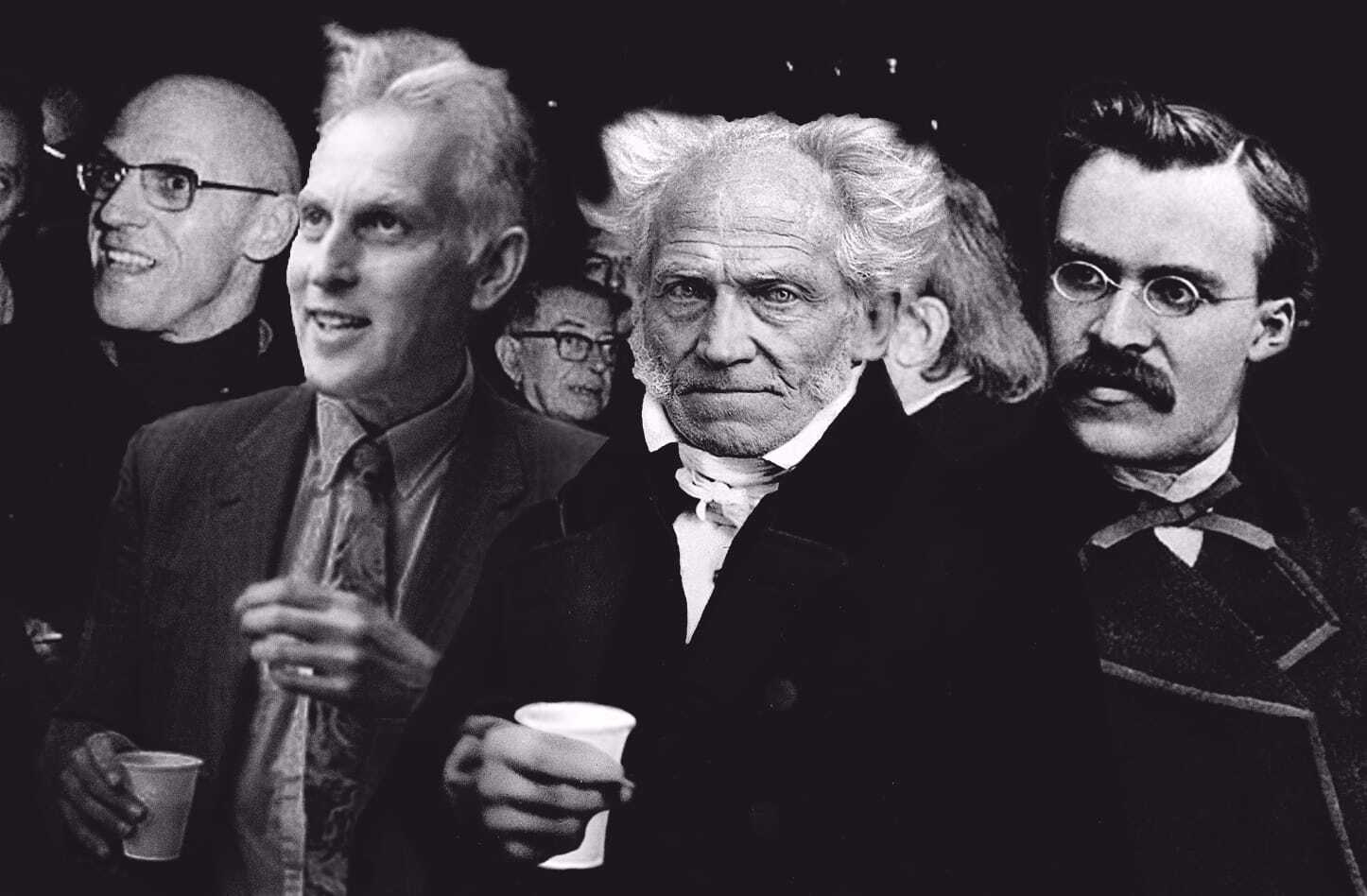

3:16: You admire Kant and yet take issue with him too don’t you and this is how your signature idea of “the World as Will” comes from isn’t it? You say he can’t say what the thinking ‘I’ is, and that’s the explanatory gap that you’re out to fill isn’t it ? Can you explain this?

AS: Firstly, it is fundamentally false that our search for higher grounds of knowledge, more general truths, springs from the presupposition of an object unconditioned in its being , that is, Kant's principle of reason, or has anything whatever in common with this. Moreover, how should it be essential to the reason to presuppose something which it must know to be an absurdity as soon as it reflects? The source of that conception of the unconditioned is rather to be found only in the indolence of the individual who wishes by means of it to get rid of all further questions, whether his own or of others, though entirely without justification.What gives unity and sequence to consciousness, since by pervading all the representations of consciousness, it is its substratum, its permanent supporter, cannot itself be conditioned by consciousness, and therefore cannot be a representation. On the contrary, it must be the ‘prius’ of consciousness, and the root of the tree of which consciousness is the fruit.

This, I say, is the ‘will ’; it alone is unalterable and absolutely identical, and has brought forth consciousness for its own ends. Without it the intellect would have no more unity of consciousness than has a mirror. Therefore the will is the true and ultimate point of unity of consciousness, and the bond of all its functions and acts. It does not, however, itself belong to the intellect, but is only its root, origin, and controller.

3:16: So do you oppose materialism?

AS: Materialism seeks the primary and most simple state of matter, and then tries to develop all the others from it; ascending from mere mechanism, to chemism, to polarity, to the vegetable and to the animal kingdom. And if we suppose this to have been done, the last link in the chain would be animal sensibility - that is knowledge - which would consequently now appear as a mere modification or state of matter produced by causality. Now if we had followed materialism thus far with clear ideas, when we reached its highest point we would suddenly be seized with a fit of the inextinguishable laughter of the Olympians. As if waking from a dream, we would all at once become aware that its final result - knowledge, which it reached so laboriously, was presupposed as the indispensable condition of its very starting-point, mere matter; and when we imagined that we thought matter, we really thought only the subject that perceives matter; the eye that sees it, the hand that feels it, the understanding that knows it. Thus the tremendous petitio principii reveals itself unexpectedly.

3:16: So what follows from this?

AS: The world is my representation. Materialism? The fundamental tenet of the Vedanta school consisted not in denying the existence of matter, that is of solidity, impenetrability, and extended figure (to deny which would be lunacy), but in correcting the popular notion of it, and in contending that it has no essence independent of mental perception; that existence and perceptibility are convertible terms.

3:16: So whether we call it idealism, transcendental idealism or materialism, is it fair to say that you’re a scientific realist about the world?

AS: In endless space countless luminous spheres, round each of which some dozen smaller illuminated ones revolve, hot at the core and covered over with a hard cold crust; on this crust a mouldy film has produced living and knowing beings: this is empirical truth, the real, the world. Yet for a being who thinks, it is a precarious position to stand on one of those numberless spheres freely floating in boundless space, without knowing whence or whither, and to be only one of innumerable similar beings that throng, press, and toil, restlessly and rapidly arising and passing away in beginningless and endless time.

3:16: So is it from the ability of science to observe the world and ourselves in the third person, so to speak, that has revealed to you our terrible predicament?

AS: It is really incredible how meaningless and insignificant when seen from without, and how dull and senseless when felt from within, is the course of life of the great majority of men. It is weary longing and worrying, a dreamlike staggering through the four ages of life to death, accompanied by a series of trivial thoughts. They are like clockwork that is wound up and goes without knowing why. Every time a man is begotten and born the clock of human life is wound up anew, to repeat once more its same old tune that has already been played innumerable times, movement by movement and measure by measure, with insignificant variations. Every individual, every human apparition and its course of life, is only one more short dream of the endless spirit of nature, of the persistent will-to-live, is only one more fleeting form, playfully sketched by it on its infinite page, space and time; it is allowed to exist for a short while that is infinitesimal compared with these, and is then effaced, to make new room. Yet, and here is to be found the serious side of life, each of these fleeting forms, these empty fancies, must be paid for by the whole will-to-live in all its intensity with many deep sorrows, and finally with a bitter death, long feared and finally made manifest. It is for this reason that the sight of a corpse suddenly makes us serious.

3:16: You characterise this vision as tragic and sublime don’t you?

AS: What gives all that is tragic, whatever its form, the characteristic of the sublime, is the first inkling of the knowledge that the world and life can give no satisfaction, and are not worth our investment in them. The tragic spirit consists in this. Accordingly it leads to resignation. We should always be mindful of the fact that no man is ever very far from the state in which he would readily want to seize a sword or poison in order to bring his existence to an end

.3:16: Science seems to be a bit of a downer!

AS: Grow up! Science is not a taxi-cab that we can get in and out of whenever we like.

3:16: And you don’t think there’s a retreat possible, into subjectivity or something like that?

AS: That’s idiotic! Astrology provides a brilliant proof of the miserable subjectivity of human beings, as a result of which they relate everything to themselves and go from every thought in a straight line immediately back to themselves. It relates the course of the great celestial bodies to the pathetic I, as it also connects the comets in the sky with earthly quarrels and shabby tricks. Every man mistakes the limits of his vision for the limits of the world.

3:16: Kant argued that there is a noumenal world of things in themselves that is unknowable to us. You seem to link it with the Vedantic conception of the Veil of Maya, and Plato’s distinction between the real world and the world of appearance. Are you a Kantian or neo-Kantian in this sense?

AS: In truth the continual coming into existence of new beings and the annihilation of already existing ones is to be regarded as an illusion produced by a contrivance of two lenses (brain-functions) through which alone we can see anything at all: they are called space and time, and in their interpenetration causality. For everything we perceive under these conditions is merely phenomenon; we do not know what things are like in themselves, i.e. independently of our perception of them. This is the actual kernel of the Kantian philosophy.

Nature is unfathomable because we seek after causes and consequences in a realm where this form is not to be found. We try to reach the inner being of nature, which looks out at us from every phenomenon, under the guidance of the principle of sufficient reason - whereas this is merely the form under which our intellect comprehends appearance, i.e. the surface of things, while we want to employ it beyond the bounds of appearance; for within these bounds it is serviceable and sufficient.

3:16: Are you a neo-Kantian idealist?

AS: I say that the empirical inscrutableness of all natural things is a proof a posteriori of the ideality and merely phenomenal-actuality of their empirical existence. I regard Kant’s doctrine of the coexistence of freedom and necessity as the greatest achievement of the human mind. With the Transcendental Aesthetic it forms the two great diamonds in Kant’s crown of fame ...

3:16: A striking feature of your approach to this rather abstruse metaphysics is that it results in an approach to living doesn’t it? This is reflected in the influence that you’ve had on the direction of Neo-Kantianism and positivism, with your focus on questions of the meaning and value of human existence playing a role in the 19 th century "identity crisis of philosophy," which still seems to haunt philosophy - and which spurred some Neo-Kantians to take up a study of human values broadly construed? Are you saying that we should live guided by this metaphysics?

AS: Yes, I’m a practical philosopher. The theoretical philosopher transforms life into ideas. The practical philosopher transforms ideas into life; he acts, therefore, in a thoroughly reasonable manner; he is consistent, regular, deliberate; he is never hasty or passionate; he never allows himself to be influenced by the impression of the moment. Only the metaphysics is actually and immediately the support to ethics which is itself originally ethical and is constructed from the substance of ethics, namely the will. Therefore, I could have called my metaphysics “ethics” with much more better reason than Spinoza. With him this looks almost like an irony, for only by sophism could he tack morality onto a system from which it would never consistently issue. Also, with almost revolting assurance he mostly flatly denies it.

3:16: So when we turn to questions of what we should do when faced with this metaphysics, you find Spinoza wanting because he’s too optimistic and Kant wanting in this as well because he lets a fetishisation of rationality ignore the consequences of the will: in short, you are against Kant’s categorical imperative aren’t you? You think of it an extreme rational asceticism?

AS: Morality is concerned with the actual conduct of man, and not with a priori building of houses of cards to whose results no man would turn in the storm and stress of life. The purpose of ethics is to indicate, explain, and to trace to its ultimate ground the extremely varied behavior of man from a moral point of view. I have shown the categorial imperative to be a futile assumption so clearly and irrefutably, that no one with a spark of judgment can possibly believe any longer in this fiction. It was possible only by a man determining himself entirely ‘rationally’ according to concepts, not according to changing impressions and moods.

Actually, Kant’s whole doctrine of categories is mere wind. Kant himself betrays his consciousness of the untenable nature of his doctrine of the categories by the fact that in the third chapter of the Analytic of Principles (phaenomena et noumena) several long passages of the first edition are omitted in the second - passages which displayed the weakness of that doctrine too openly. So, for example, he says there that he has not defined the individual categories, because he could not define them even if he had wished to do so, inasmuch as they were susceptible of no definition. In saying this he forgot that in the same first edition he had said: “I purposely dispense with the definition of the categories although I may be in possession of it." Like I said, this then was, sit venia verbo , wind.

3:16: What do you put in its place?

AS: As only the maxims of our conduct, not the consequences or circumstances, are in our power, to be capable of always remaining consistent we must take as our object only the maxims, not the consequences and circumstances, and thus the doctrine of virtue is again introduced.

3:16: What virtue?

AS: Give way neither to love nor to hate, is one-half of worldly wisdom: say nothing and believe nothing, the other half. Compassion is the most likely alleviation of the countless and multifarious sufferings with which our life is beset and which no one completely escapes, and at the same time compassion is the counterbalance to the burning egoism that fills all beings and often develops into malice. Boundless compassion for all living beings is the firmest and most certain guarantee of moral good conduct and requires no casuistry. Whoever is filled with it will certainly injure no one, infringe on no one, do no one harm, rather, forbear everyone, forgive everyone, help everyone as much as he can, and all his actions will carry the imprint of justice and loving kindness.

3:16: So do you think there are objective morals?

AS: Of course not! Every ought simply has no sense and meaning except in relation to threatened punishment or promised reward … .thus every ought is necessarily conditioned through punishment or reward, hence, to put it in Kant’s terms, essentially and inevitably hypothetical [with if-clause] and never, as he maintains categorical [without if-clause] … Therefore an absolute ought is simply a contradictio in adjecto .

3:16: Why do you think we don’t have freewill in the way most people understand the term?

AS: In order to elucidate especially and most clearly the origination of this error let us imagine a man who, while standing on the street, would say to himself: "It is six o'clock in the evening, the working day is over. Now I can go for a walk, or I can go to the club; I can also climb up the tower to see the sunset; I can go to the theater; I can visit this friend or that one; indeed, I also can run out of the gate, into the wide world, and never return. All of this is strictly up to me, in this I have complete freedom. But still I shall do none of these things now, but with just as free a will I shall go home to my wife". This is exactly as if water spoke to itself: "I can make high waves (yes! in the sea during a storm), I can rush down hill (yes! in the river bed), I can plunge down foaming and gushing (yes! in the waterfall), I can rise freely as a stream of water into the air (yes! in the fountain), I can, finally boil away and disappear (yes! at a certain temperature); but I am doing none of these things now, and am voluntaringly remaining quiet and clear water in the reflecting pond.

3:16: So is it the Will of our inner natures, over which we have no control, that determines our actions and thoughts?

AS: Yes. Spinoza says that if a stone which has been projected through the air, had consciousness, it would believe that it was moving of its own free will. I add this only, that the stone would be right. The impulse given it is for the stone what the motive is for me, and what in the case of the stone appears as cohesion, gravitation, rigidity, is in its inner nature the same as that which I recognise in myself as will, and what the stone also, if knowledge were given to it, would recognise as will. A man can do what he wants but not want what he wants.

3:16: So there’s no causa sui that would grant us freewill by escaping determinism?

AS: Of course not! The true emblem of causa sui is Baron Münchhausen, who, clamping his legs around his horse as it sinks in the water, pulls his pigtail up over his head and raises himself and the horse into the heights; under this emblem, put: causa sui .

3:16: So are we all biologically fated?

AS: Fate shuffles the cards and we play. The life of the individual is only borrowed from that of the species. Mind you, what people commonly call fate is mostly their own stupidity.

3:16: You link ‘willing’ to suffering don’t you?

AS: All willing springs from lack, from deficiency, and thus from suffering. Fulfillment brings this to an end; yet for one wish that is fulfilled there remain at least ten that are denied. Further, desiring lasts a long time, demands and requests go on to infinity, fulfillment is short and meted out sparingly. But even the final satisfaction itself is only apparent; the wish fulfilled at once makes way for a new one; the former is a known delusion, the latter not as yet known. No attained object of willing can give satisfaction that lasts and no longer declines… to combine the object with its superficial appearance is difficult, when it is not impossible. Indeed that is just the curse of this world of want and need, that everything must serve and slave for these; and therefore it is not so constituted that any noble and sublime effort, like the endeavour after light and truth, can prosper unhindered and exist for its own sake.

3:16: Is this why you think we’re never fulfilled?

AS: Yes. So long as our consciousness is filled by our will, so long as we are given up to the throng of desires with its constant hopes and fears, so long as we are the subject of willing, we never obtain lasting happiness or peace…

3:16: Can you summarise what this will is?

AS: The will as thing-in-itself is entire and undivided in every being, just as the centre is an integral part of every radius; whereas the peripheral end of this radius is in the most rapid revolution with the surface that represents time and its content, the other end at the centre where eternity lies, remains in profoundest peace, because the centre is the point whose rising half is no different from the sinking half. Therefore, it is said also in the ‘Bhagavad-Gita’: “Undivided it dwells in beings, and yet as it were divided; it is to be known as the sustainer, annihilator, and producer of beings”. Here, of course, we fall into mystical and metaphorical language, but it is the only language in which anything can be said about this wholly transcendent theme.

3:16: So is your approach to life one a bit like the Buddhist or Stoic who strives to overcome desire, of that willing thing?

AS: Yes. If I were to take the results of my philosophy as the standard of truth, I would have to consider Buddhism the finest of all religions. The wise man does not seek pleasure but freedom from care and pain. Man is the dream of a shadow. Of every event in our life we can say only for one moment that it is; for ever after, that it was. Every evening we are poorer by a day. It might, perhaps, make us mad to see how rapidly our short span of time ebbs away; if it were not that in the furthest depths of our being we are secretly conscious of our share in the exhaustible spring of eternity, so that we can always hope to find life in it again. Most of our suffering lies in retrospect or anticipation.

3:16: Yea, pretty Buddhist , a bit like the Mahayana account of compassion in Shantideva’s The Way of the Bodhisattva. And your views on suffering cohere with Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings too . Are you saying that seeing the truth of our fate is the start of virtuous living and gets us out of life’s horror show of pain and suffering?

AS: The ancient wisdom of the Indian philosophers declares, “It is Mâyâ, the veil of deception, which blinds the eyes of mortals, and makes them behold a world of which they cannot say either that it is or that it is not: for it is like a dream; it is like the sunshine on the sand which the traveller takes from afar for water, or the stray piece of rope he mistakes for a snake.” It’s Stoical too. In conformity with this spirit and aim of the Stoa, Epictetus begins with it and constantly returns to it as the kernel of his philosophy, that we should bear in mind and distinguish what depends on us and what does not, and thus should not count on the latter at all. In this way we shall certainly remain free from all pain, suffering, and anxiety.

Now what depends on us is the will alone, and here there gradually takes place a transition to a doctrine of virtue, since it is noticed that, as the external world that is independent of us determines good and bad fortune, so inner satisfaction or dissatisfaction with ourselves proceeds from the will. But later it was asked whether we should attribute the names ‘bonum et malum’ to the two former or to the two latter. This was really arbitrary and a matter of choice, and made no difference.

3:16: What about the exciting stuff of life, it's wildness and risk, its entertainments?

AS: The genuine philosopher will generally seek lucidity and clarity and will always strive not to be like a turbid, raging, rain-swollen stream, but much more like a Swiss lake, which, in its peacefulness, combines great depth with a great clarity that just reveals its great depth.

3:16: Sounds like a dull party.

AS: The great affliction of all philistines like you Richard is that they have no interest in ideas, and that, to escape being bored, they are in constant need of realities. But realities are either unsatisfactory or dangerous; when they lose their interest, they become fatiguing. But the ideal world is illimitable and calm, something afar from the sphere of our sorrow.

3:16: It sounds as if we shouldn’t be interested in our own egos?

AS: Not at all. If we were not all so interested in ourselves, life would be so uninteresting that none of us would be able to endure it.

3:16: But overcoming the will to live is what you’re recommending, a bit like Mahayana Buddhism’s “Middle Way,” as the path to overcoming suffering. So does this make you an ascetic?

AS: Of course! Asceticism is the denial of the will to live; and the transition from the Old Testament to the New, from the dominion of Law to that of Faith, from justification by works to redemption through the Mediator, from the domain of sin and death to eternal life in Christ, means, when taken in its real sense, the transition from the merely moral virtues to the denial of the will to live.

3:16: So it replaces a world of pure justice for one of justice tempered by mercy? That's attractive and humane. But it seems that when I get rid of the will to live I'm left with nothing?

AS: Well, what remains after the complete abolition of the will, for all those who are still full of will, is assuredly nothing. But conversely, to those in whom the will has turned and denied itself, this very real world of ours with all its suns and galaxies, is – nothing. You could just as well call your mode of life the greatest folly: for that which in a moment ceases to exist, which vanishes as completely as a dream, cannot be worth any serious effort.

Life itself is a sea full of rocks and whirlpools that man avoids with the greatest caution and care, although he knows that, even when he succeeds with all his efforts and ingenuity in struggling through, at every step he comes nearer to the greatest, the total, the inevitable and irremediable shipwreck, indeed even steers right on to it, namely death. This is the final goal of the wearisome voyage, and is worse for him than all the rocks that he has avoided.

3:16: But why is it that you think we shouldn’t aim to be happy? Even if the world is a pretty terrible place, even if we fail, surely we should strive for some happiness? Surely we need to give everyone – and perhaps especially young people - a sense that happiness is attainable ?

AS: What disturbs and depresses young people is the hunt for happiness on the firm assumption that it must be met with in life. From this arises constantly deluded hope and so also dissatisfaction. Deceptive images of a vague happiness hover before us in our dreams, and we search in vain for their original. Much would have been gained if, through timely advice and instruction, young people could have had eradicated from their minds the erroneous notion that the world has a great deal to offer them. There is only one inborn error, and that is the notion that we exist in order to be happy. So long as we persist in this inborn error the world seems to us full of contradictions. For at every step, in things great and small, we are bound to experience that the world and life are certainly not arranged for the purpose of maintaining a happy existence, hence the countenances of almost all elderly persons wear the expression of what is called disappointment.

A man is never happy, but spends his whole life in striving after something that he thinks will make him so; he seldom attains his goal, and when he does, it is only to be disappointed; he is mostly shipwrecked in the end, and comes into harbour with mast and rigging gone. And then, it is all one whether he is happy or miserable; for his life was never anything more than a present moment always vanishing; and now it is over.

3:16: Do you think overcoming pain is more important than experiencing pleasure?

AS: The happiest lot is not to have experienced the keenest delights or the greatest pleasures, but to have brought life to a close without any very great pain, bodily or mental.

3:16: If life is so terrible, why continue? Should we all commit suicide and never breed?

AS: They tell us that suicide is the greatest piece of cowardice; that only a madman could be guilty of it; and other insipidities of the same kind; or else they make the nonsensical remark that suicide is wrong; when it is quite obvious that there is nothing in the world to which every man has a more unassailable title than to his own life and person. But death is the true inspiring genius, or the muse of philosophy, wherefore Socrates has defined the latter as θανάτου μελέτη. Indeed without death men would scarcely philosophise. He who has lost all hope has also lost all fear.

As for breeding: If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone, would the human race continue to exist? Would not a man rather have so much sympathy with the coming generation as to spare it the burden of existence, or at any rate not take it upon himself to impose that burden upon it in cold blood? To put this all together Richard: The will of the individual is dwarfed by the will of the species - for every suicide, there are thousands of unwilling births.

3:16: So we go on even though there’s nothing wrong with suicide and good reasons not to have children. We can live on if we want, but as realists?

AS: Indeed. In other words, we should live with due knowledge of the course of things in the world. For whenever a man in any way loses self-control, or is struck down by a misfortune, grows angry, or loses heart, he shows in this way that he finds things different from what he expected, and consequently that he laboured under a mistake, did not know the world and life, did not know how at every step the will of the individual is crossed and thwarted by the chance of inanimate nature, by contrary aims and intentions, even by the malice inspired in others. Therefore either he has not used his reason to arrive at a general knowledge of this characteristic of life, or he lacks the power of judgement, when he does not again recognize in the particular what he knows in general, and when he is therefore surprised by it and loses his self-control. Thus every keen pleasure is an error, an illusion, since no attained wish can permanently satisfy, and also because every possession and every happiness is only lent by chance for an indefinite time, and can therefore be demanded back in the next hour. Thus both originate from defective knowledge. Therefore the wise man always holds himself aloof from jubilation and sorrow, and no event disturbs his ataraxia.

3:16: It seems a bit lonely?

AS: What a man is in himself, what accompanies him when he is alone, what no one can give or take away, is obviously more essential to him than everything he has in the way of possessions, or even what he may be in the eyes of the world. An intellectual man in complete solitude has excellent entertainment in his own thoughts and fancies, while no amount of diversity or social pleasure, theatres, excursions and amusements, can ward off boredom from a dullard.

3:16: You liken society to a porcupine colony don’t you?

AS: It’s a helpful metaphor! A number of porcupines huddled together for warmth on a cold day in winter; but, as they began to prick one another with their quills, they were obliged to disperse. However the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another. In the same way the need of society drives the human porcupines together, only to be mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of their nature. The moderate distance which they at last discover to be the only tolerable condition of intercourse, is the code of politeness and fine manners; and those who transgress it are roughly told—in the English phrase—to keep their distance. By this arrangement the mutual need of warmth is only very moderately satisfied; but then people do not get pricked. A man who has some heat in himself prefers to remain outside, where he will neither prick other people nor get pricked himself.

3:16: Is society, and being sociable, something we should be avoiding then?

AS: Not totally. As a reliable compass for orientating yourself in life nothing is more useful than to accustom yourself to regarding this world as a place of atonement, a sort of penal colony. When you have done this you will order your expectations of life according to the nature of things and no longer regard the calamities, sufferings, torments and miseries of life as something irregular and not to be expected but will find them entirely in order, well knowing that each of us is here being punished for his existence and each in his own particular way. This outlook will enable us to view the so-called imperfections of the majority of men, i.e., their moral and intellectual shortcomings and the facial appearance resulting therefrom, without surprise and certainly without indignation: for we shall always bear in mind where we are and consequently regard every man first and foremost as a being who exists only as a consequence of his culpability and whose life is an expiation of the crime of being born.

3:16: So the solitude is something you train yourself to have no matter what you’re doing?

AS: Let me advise you to form the habit of taking some of your solitude with you into society, to learn to be to some extent alone even though you are in company; not to say at once what you think, and, on the other hand, not to attach too precise a meaning to what others say; rather, not to expect much of them, either morally or intellectually, and to strengthen yourself in the feeling of indifference to their opinion, which is the surest way of always practicing a praiseworthy toleration. If you do that, you will not live so much with other people, though you may appear to move amongst them: your relation to them will be of a purely objective character. This precaution will keep you from too close contact with society, and therefore secure you against being contaminated or even outraged by it. Society is in this respect like a fire—the wise man warming himself at a proper distance from it; not coming too close, like the fool, who, on getting scorched, runs away and shivers in solitude, loud in his complaint that the fire burns.

3:16: As a push back, there are those who might argue that there are positive values to being sociable, that we learn to love and respect others and ourselves from social interactions. I personally quite like socializing and during the lockdown many people have felt depressed because they haven’t been able to socialize. What would you say to that line of thought?

AS: Rascals are always sociable Richard, and the chief sign that a man has any nobility in his character is the little pleasure he takes in others company.

3:16: Some people think being polite is phony and being rude is honest– do you agree?

AS: Phony isn’t always bad. It is a wise thing to be polite; consequently, it is a stupid thing to be rude. To make enemies by unnecessary and willful incivility, is just as insane a proceeding as to set your house on fire. For politeness is like a counter--an avowedly false coin, with which it is foolish to be stingy.

3:16: What do you think about falling in love and marriage and that stuff?

AS: Since love is a deception practiced by nature, marriage is the attrition of love and must be disillusioning. Only a philosopher can be happy in marriage and philosophers do not marry.

3:16: But you also see signs of our true natures in people who are in love don’t you?

AS: Why does the man in love hang with complete abandon on the eyes of his chosen one, and is ready to make every sacrifice for her? Because it is his immortal part that longs for her; it is always the mortal part alone that longs for everything else. That eager and even ardent longing, directed to a particular woman, is therefore an immediate pledge of the indestructibility of the kernel of our true nature…

3:16: So what kind of life should we be aiming for if not a happy one? If life is without value, what should we do?

AS: If life — the craving for which is the very essence of our being — were possessed of any positive intrinsic value, there would be no such thing as boredom at all: mere existence would satisfy us in itself, and we should want for nothing. A happy life is impossible, the highest thing that man can aspire to is a heroic life; such as a man lives, who is always fighting against unequal odds for the good of others; and wins in the end without any thanks. After the battle is over, he stands like the Prince in the re corvo of Gozzi, with dignity and nobility in his eyes, but turned to stone. His memory remains, and will be reverenced as a hero's; his will, that has been mortified all his life by toiling and struggling, by evil payment and ingratitude, is absorbed into Nirvana.

What I have here described with feeble tongue and only in terms, is no philosophical fable, invented by myself, and only of today; no, it was the enviable life of so many saints and beautiful souls among Christians, and still more among Hindus and Buddhists and also among the believers of other religions.

3:16: Still, this heroism comes from a rather gloomy place?

AS: There is some wisdom in taking a gloomy view, in looking upon the world as a kind of Hell, and in confining one's efforts to securing a little room that shall not be exposed to the fire.

3:16: I like a laugh. You sometimes sound a bit dry and serious all the time. Do you value a sense of humour?

AS: A sense of humour is the only divine quality of man.

3:16: Is there evil beyond the terrible nature of life?

AS: No. Evil is just what is positive; it makes its own existence felt.

3:16: You think art important don’t you, and see poetry and philosophy as being linked in some way?

AS: What might otherwise be called the finer part of life, its purest joy, just because it lifts us out of real existence and transforms us into disinterested spectators of it, is pure knowledge which remains foreign to all willing, pleasure in the beautiful, genuine delight in art. Poetry is related to philosophy as experience is related to empirical science. Experience makes us acquainted with the phenomenon in the particular and by means of examples, science embraces the whole of phenomena by means of general conceptions. So poetry seeks to make us acquainted with the Platonic Ideas through the particular and by means of examples. Philosophy aims at teaching, as a whole and in general, the inner nature of things which expresses itself in these. One sees even here that poetry bears more the character of youth, philosophy that of old age. And music is an unconscious exercise in metaphysics in which the mind does not know it is philosophizing, is a copy of Will itself.

3:16: You also put a high value on friendship and and link this to understanding compassion and the intimate link between the world and ones ego– so again is friendship endorsed by the metaphysics?

AS: The bad (that is, uncompassionate] man everywhere feels a thick partition between himself and everything outside him. The world to him is an absolute non-ego and his relation to it is primarily hostile; thus the keynote of his disposition is hatred, spitefulness, suspicion, envy, and delight at the sight of another's distress. The good character, on the hand, lives in an external world that is homogeneous with his own true being. The others are not a non-ego for him, but an 'I once more'. His fundamental relation to everyone is, therefore, friendly; he feels himself intimately akin to all beings, takes an immediate interest in their weal and woe, and confidently assumes the same sympathy with them. The results of this are his deep inward peace and the confident, calm, and contented mood by virtue of which everyone is happy when he is near at hand.

3:16: Your compassion doesn’t end with humans does it?

AS: Compassion is the basis of morality. The assumption that animals are without rights and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality. Compassion for animals is intimately associated with goodness of character, and it may be confidently asserted that he who is cruel to animals cannot be a good man.

3:16: You’ve said some pretty sexist things about women. Are you sexist?

AS: Foolish man! I have not yet spoken my last word about women. I believe that if a woman succeeds in withdrawing from the mass, or rather raising herself from above the mass, she grows ceaselessly and more than a man.

3:16: We’re living in very moralistic times and your approach - ‘live and let live’ – doesn’t seem to be doing very well. Why do you think this new attitude is a mistake?

AS: No one who has to live amongst men should absolutely discard any person who has his due place in the order of nature, even though he is very wicked or contemptible or ridiculous. He must accept him as an unalterable fact—unalterable, because the necessary outcome of an eternal, fundamental principle; and in bad cases he should remember the words of Mephistopheles: es muss auch solche Käuze geben— there must be fools and rogues in the world. If he acts otherwise, he will be committing an injustice, and giving a challenge of life and death to the man he discards.

No one can alter his own peculiar individuality, his moral character, his intellectual capacity, his temperament or physique; and if we go so far as to condemn a man from every point of view, there will be nothing left him but to engage us in deadly conflict; for we are practically allowing him the right to exist only on condition that he becomes another man—which is impossible; his nature forbids it.

3:16: Noisy toxic populism is also all the rage, with exaggerating and outraged mobs even in iuniversities and the media. Does this depress you?

AS: Well, if you want to earn the gratitude of your own age you must keep in step with it. But if you do that you will produce nothing great. If you have something great in view you must address yourself to posterity: only then, to be sure, you will probably remain unknown to your contemporaries; you will be like a man compelled to spend his life on a desert island and there toiling to erect a memorial so that future seafarers shall know he once existed. Through neglect of this rule, many men of genius and great scholars have become weak-minded and childish, or even gone quite mad, as they grew old.

To take no other instances, there can be no doubt that the celebrated English poets of the early part of my century, Scott, Wordsworth, Southey, became intellectually dull and incapable towards the end of their days, nay, soon after passing their sixtieth year; and that their imbecility can be traced to the fact that, at that period of life, they were all led on by the promise of high pay, to treat literature as a trade and to write for money. This seduced them into an unnatural abuse of their intellectual powers; and a man who puts his Pegasus into harness, and urges on his Muse with the whip, will have to pay a penalty similar to that which is exacted by the abuse of other kinds of power.

As to the media: Exaggeration in every sense is as essential to newspaper writing as it is to the writing of plays: for the point is to make as much as possible of every occurrence. So that all newspaper writers are, for the sake of their trade, alarmists: this is their way of making themselves interesting. If this world were populated with really thinking beings, it would be impossible for all kinds of noise to be permitted and given such unlimited scope, even the most terrible and purposeless. But if nature had intended man for thinking, she would not have given him ears, or at any rate would have furnished them with air-tight flaps, as with bats whom for this reason I envy.

3:16: How important is language to your philosophy? You see it as having coordinating value don't you?

AS: Yes. Only by the aid of language does reason bring about its most important achievements, namely the harmonious and consistent action of several individuals, the planned cooperation of many thousands, civilization, the State; and then, science, the storing up of previous experience, the summarizing into one concept of what is common, the communication of truth, the spreading of error, thoughts and poems, dogmas and superstitions. The animal learns to know death only when he dies, but man consciously draws every hour nearer his death; and at times this makes life a precarious business, even to the man who has not already recognized this character of constant annihilation in the whole of life itself.

3:16: Would the world be a better place if we treated everyone with dignity?

AS: No. The way to keep down hatred and contempt is certainly not to look for a man's alleged "dignity," but, on the contrary, to regard him as an object of pity. It seems to me that the idea of dignity can be applied only in an ironical sense to a being whose will is so sinful, whose intellect is so limited, whose body is so weak and perishable as man's. How shall a man be proud, when his conception is a crime, his birth a penalty, his life a labour, and death a necessity!

3:16: Finally, there’s a young guy called Nietzsche coming through with an answer to your pessimism. Do you think he has a point when he says it isn’t suffering per se but meaningless suffering that’s the problem, so your diagnosis is wrong? He also rejects any form of asceticism.

AS: The actual facts of morality are too much on my side for me to fear that my theory can ever be replaced or upset by any other.

3:16: For the readers here at 3:16, can you recommend 5 books that will help us get further into your philosophical world?

AS: No, I'll give you six.

Aristotle : Physics

Bhagavadgita

Epictetus: The Stoic Way of Life

The Mahayana Uttaratantra Shastra

Kant: Critique of Pure Reason

Plato: Symposium

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time

Previous: 3:16 interviews in the series with Nietzsche and Debord