Stewart Home's Fascist Yoga

There is a sickness in the body of modern yoga and Stewart Home wants us to see it for what it is: not a late-stage infection brought on by QAnon, Trumpism, or pandemic conspiracies, but a long-standing condition baked deep into the cultural and political marrow.

Fascist Yoga, his bracing and often incendiary intervention, opens not with scholarly detachment but with a scene of personal excavation: digging through the traces of his mother’s life, Home stumbles upon a fascist antiques dealer with ties to far-right terror networks. The name is Bill Hopkins. The context is 1980s Britain. But the feeling of something sinister hidden behind the decorative mask of heritage, ritual, and mysticism will return years later as Home surveys the strange terrain of Western yoga culture. What he finds is a network of essentialist fantasies, occult longings, pseudoscientific claims, and spiritual hierarchies, all cloaked in the language of peace and wellness yet saturated with authoritarian logics.

From the outset, Home wants to disabuse us of the notion that yoga’s flirtation with fascism is some recent glitch. The pandemic, he argues, did not cause the problem; it merely revealed the rot that was always there. Anti-vaccine protests, New Age QAnon influencers, and yoga instructors denouncing public health as spiritual tyranny are not accidents but expressions of yoga’s deeper susceptibility to what he calls countercultural fascism. This is not the fascism of jackboots and uniforms but of mandalas and mala beads, of ‘higher truths’ that scorn empirical evidence, of gurus who claim divine authority while engaging in abuse, of an aestheticised politics that hides hierarchy behind healing.

At the heart of Home’s project is a provocation many yoga practitioners will resist: that the modern postural yoga movement is not a timeless Indian tradition but a Western invention entangled from the beginning with esotericism, show business, occultism, and authoritarian spiritualism. His examples are often lurid but always well-sourced: a MAGA yoga influencer posing in front of a fascist flag, a tarot-reading Nazi in the American Freedom Party who teaches sun salutations alongside racial purity, a yoga school in Italy whose founder invokes Gabriele D’Annunzio while selling certification in spiritual “freedom.” These are not outliers, Home insists, but signals, emissaries from a submerged ideological core. What distinguishes Fascist Yoga from recent critiques like the Conspirituality podcast is its refusal to offer rescue narratives. This is, of course, Home’s signature move. While others still hope to salvage some purified version of yoga, stripped of its spiritual excesses and political misuses, Home sees the structure as irredeemable.

The problem, he argues, is not misuse but use, the very framework of mystical essentialism, guru-devotion, and pseudoscientific belief that modern yoga is built upon. Like the fascist ideologies it sometimes overlaps with, yoga offers the illusion of wholeness, order, and transcendent unity. And like those ideologies, it does so by denying doubt, complexity, and evidence. In a voice that is by turns satirical, forensic, and sharply autobiographical, Home urges readers to look past the incense and Sanskrit and see what modern yoga has always been: a mirror in which the West projects its fantasies of the East, its longing for submission, its anti-modern backlash against science, materialism, and democracy. Whether he is dissecting the fabricated guru lineages of Pierre Bernard or exposing the racial mysticism behind neo-folk music scenes, Home returns again and again to a single claim: that the appeal of modern yoga is not despite its authoritarian tendencies but because of them. The result is a book that dares to ask whether the sun salutations of suburbia might be closer to the salutes of Nuremberg than we care to imagine. This line of critique culminates in Home’s demolition of contemporary yoga as a self-erasing form of historical violence, an active forgetting not only of yoga’s imperial entanglements but of its co-emergence with fascist aesthetics, masculinist transcendence, and racialised metaphysics. The sanitized, secular yoga class in a gentrified urban studio is not a neutral space for mind-body alignment but, for Home, the latest iteration of a political theology that once animated swastika-bearing yogis and continues to structure liberal subjectivity today.

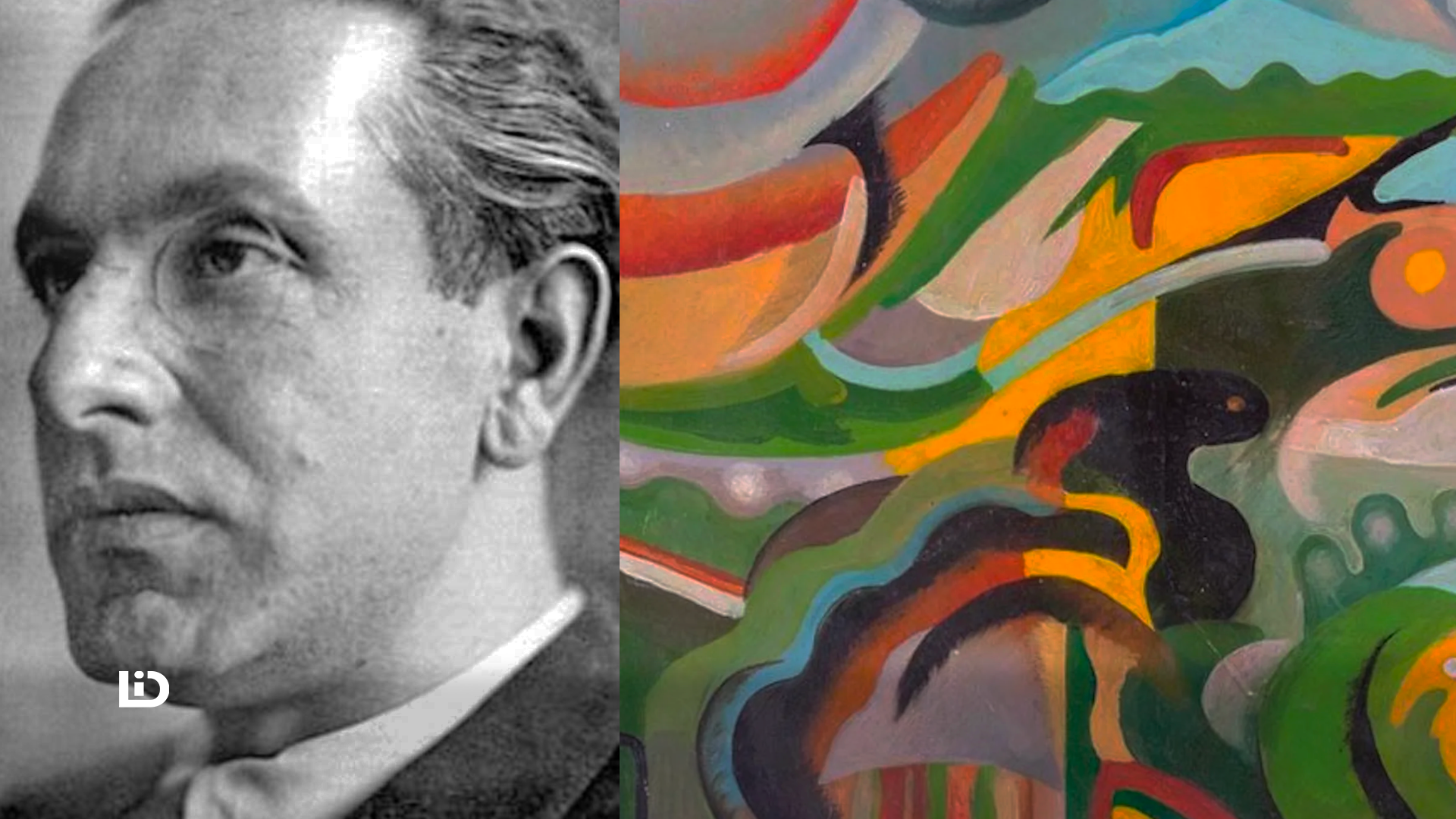

[Evola]

What links Evola’s esoteric elitism to Lululemon’s athleisure consumer is not simply Orientalism or capitalism, it is the deeper fantasy of transcendental mastery over body, history, and collective vulnerability. Home’s argument thus turns away from the usual liberal critique of appropriation, which too often presumes a stable core of ‘authentic’ culture that has been violated by Western commodification. Instead, he insists that what is marketed as ‘yoga’ was always a hybridised, mythic construction, born of colonial power and fascist aesthetics. The problem, then, is not that yoga has been appropriated from a pure source but that its source itself is entangled with domination. Bernard’s mysticism, Keller’s swastikas, D’Annunzio’s spectacles, and the silent conformity of the modern yoga class are not successive corruptions of an authentic tradition, they are expressions of the same political unconscious.

This insight allows Home to unmask the neoliberal ‘diversity’ campaigns in modern wellness culture for what they are: compensatory rituals that disavow the deeper racial and class hierarchies that structure global yoga capitalism. The token inclusion of Indian gurus on YouTube or the celebration of ‘brown yogis’ on Instagram does nothing to challenge the deeper architecture of racialised market spirituality. In fact, such gestures often serve as what lefty guru influencer Slavoj Žižek might call ideological ‘fetish disavowals: yes, the industry is historically white and elitist, but look, here’s a woman of color doing inversions in Bali, so everything’s fine.

What emerges from Fascist Yoga is a vision of yoga not as a corrupted good but as a technique of spiritual-political governance: a bodily liturgy that reproduces obedience, quietism, and a hollowed-out sovereignty. Its mantra is not ‘liberation,’ but ‘alignment’, with power, with market logic, with racial capital’s subtle disciplines. Home’s proposed response is not reform, nor is it a nostalgic return to some supposedly decolonial origin. It is rupture. Home insists on exposing and interrupting the affective infrastructures that sustain fascist spirituality, from the fetish of ‘inner peace’ to the silent consensus of studio etiquette. His is a call for an antagonistic spirituality, one that embraces conflict, names domination, and reclaims bodily practice as a site of historical reckoning rather than metaphysical escape. Stage one: buy his book. Second stage: read it!!!

Home begins resurrecting the cultural memory wars surrounding the Rijeka Yoga Group and their theatrical occupation of Fiume, a proto-fascist spectacle that fused D’Annunzian aestheticism, militarised mysticism, and violent racial politics under the banner of ‘sacred love.’ Far from being a historical curiosity, Home exposes how figures like Guido Keller and Giovanni Comisso prefigured a recurring fascist strategy: the co-optation of esoteric, often pseudo-Hindu imagery to legitimize racialised sovereignty and militarized elitism. That Modi has literally instantiated this as the hegemonic fascist politics of contemporary India only substantiates Home’s point. The YOGA group’s symbolic ‘Tenth Corporation,’ reserved for “superior individuals” of mystical potential, offered not only an aestheticised caste hierarchy but a proto-political theology of fascist selection, what Carl Schmitt would recognize as the sovereign act of deciding who belongs within the sacred circle of political community and who must be excluded.

This fascist spiritualism was not some fringe eccentricity. Its fetish for symbolic violence of battle games with grenades, the Desperates' theatrical militarism, swastika banners all served to enact the friend/enemy distinction with baroque excess. YOGA’s obsession with inner transformation through erotic mysticism and neo-Hindu symbols (their so-called ‘science of love’) cloaked this violence in the language of transcendence, making Keller and Comisso’s group not a parody of religion but a fascist liturgy: a liturgy of hierarchy, purification, and aestheticised domination.

[Haur]

Such excesses were not isolated. Julius Evola’s vision of a Vedic warrior caste, Jakob Wilhelm Hauer’s attempts to root Nazism in Aryan Upanishadic spirituality, and even Savitri Devi’s grotesque fusion of Hitler-worship with Krishna devotion all follow the same ideological contour traced by Keller and YOGA: a sacralisation of fascism through Orientalist mysticism. Mircea Eliade’s flirtations with far-right nationalism and mythic cyclical time further consolidate this intellectual trend, where yoga ceases to be a practice of liberation and becomes, instead, an instrument of spiritual authoritarianism. Home’s excavation does more than name these figures, it maps a transnational genealogy of fascist yoga: from Bernard’s white Aryan tantra circles in America to D’Annunzio’s erotic militias and Evola’s transcendent spiritual aristocracy. Each instance relies on the same sleight of hand: the transformation of yoga from a complex, historically grounded South Asian soteriology into a universalising, racialized, and elitist technology of will.

The promise is always the same: to transcend bourgeois mediocrity through spiritual violence, to found a new order beyond liberal democracy’s degeneracy. This ideological alchemy persists in the present. Home draws a sharp line connecting the historical fascist yogis and today’s globalized yoga industry, where sanitized ‘studio spirituality’ continues the legacy of bodily discipline and docile subjectivity. The yoga mat in a luxury condo becomes a silent echo of the Desperates’ militarised dance; the neoliberal yogi’s quest for balance becomes a mirror image of Evola’s spiritual conquest. Even when the iconography shifts from swastikas to mandalas, the structural function remains: yoga as a technology of inner order that obscures outer violence. Just as Keller’s YOGA masked racial nationalism in the idiom of mystical eroticism, today’s yoga scene masks capitalist domination in the language of mindfulness.

From a Black Atlantic Marxist perspective, Home insists that this is no accident. We may speculate that drawing on the likes of Cedric Robinson and Paul Gilroy, Home frames fascist yoga not as a cultural anomaly but as a spiritualised articulation of racial capitalism, a mystified infrastructure that spiritualises empire, re-enchants domination, and repackages hierarchy as transcendence. Even when contemporary practitioners do not explicitly espouse fascism, their inherited forms, the postures, the breathwork, the aesthetic all bear the sedimented legacy of fascist mystification. Thus, the question Home poses is not simply ‘Is yoga fascist?’ but rather: 'how has yoga become a vessel for authoritarian longing, aestheticised obedience, and spiritualized sovereignty?' In the ritualised exclusion of the unfit, the dark-skinned, the non-awakened, in the fetishisation of spiritual elites and warrior selves, in the relentless focus on self-perfection without social antagonism Home hears the old song of the YOGA group echoing beneath the Om.

And when revisionists attempt to sanitise these legacies, as in Aidan O’Malley’s account of the Trieste exhibition celebrating D’Annunzio’s occupation of Fiume, Home sounds the alarm. These are not mere historiographical disagreements. They are ideological skirmishes in a broader hybrid war, where neo-fascists openly reclaim the esoteric militancy of Keller and Evola, while liberals nervously clutch their chakras, hoping the violence stays historical. But the legacy lives on, precisely because its seductive aesthetics have not been dismantled, only rebranded. In this light, the resurgence of fascist spirituality today, from far-right ashrams to yoga influencers flirting with “natural hierarchy”, is not a glitch but a continuation, a feature not a bug. What Home offers is not nostalgia for a pure, untainted yoga - he dismisses that fantasy as thoroughly as he dismisses liberal wellness. Instead, he calls for a radical negation: the unmasking of yoga’s ideological function and the refusal to participate in a tradition whose roots, when traced honestly, wind through the ruins of Fiume, the Aryan fantasies of Evola, and the studio mirrors of neoliberal spiritual capitalism.

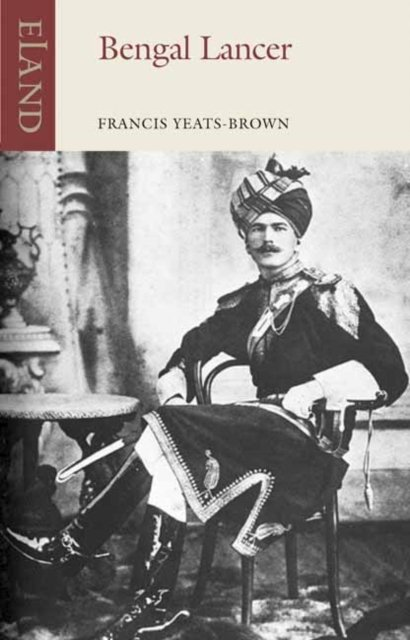

His excavation of Yeats-Brown, an obscure but important figure in the book, shows that Yeats-Brown’s myth-making, like Fuller’s, was not merely a matter of personal vanity or literary embellishment but was central to the ideological work that fascist yoga performs. His strategic disavowal of Pierre Bernard, coupled with the projection of a mystical apprenticeship under Indian gurus, replicates the classic structure of fascist esotericism: conceal the real (Western, often occultist and racialised) sources, and replace them with an Orientalist fantasy of authentic initiation. In this sense, Home exposes Yeats-Brown not just as a liar, but as a cultural technician of fascism, one who instrumentalised yoga’s symbolic capital to legitimize a broader project of racial mysticism, imperial nostalgia, and authoritarian masculinity. In so doing Home points to how contemporary fascism can instrumentalise anything for its own end. This nostalgic imperialism was not a backdrop but a generative matrix. Home demonstrates how Yeats-Brown’s memoirs functioned as colonial propaganda disguised as spiritual autobiography.

In Bengal Lancer, yoga becomes a metaphor for the disciplined, stoic, self-overcoming soldier, a mystical analogue to the imperial mission. The image of the yogic British officer, conquering both body and terrain, blends Victorian muscular Christianity with racial mysticism. Home’s analysis thus pierces the ideological veil of Yeats-Brown’s prose, revealing it as a reactionary fantasy in which the fallen imperial subject reclaims his dominance not through arms but through the posture and breath of the Orientalised self. Furthermore, Yeats-Brown’s performances of gender and spiritual discipline - cross-dressing as a German governess, tales of fever control and defecation mastery - become part of the fascist erotics of transformation. Like the Desperates of the Rijeka YOGA group, Yeats-Brown transfigures humiliation into myth. The fallen imperial man, stripped of power, undergoes a rite of passage that is at once spiritual, militaristic, and theatrical. This is the fascist script: crisis, humiliation, transcendence through discipline, rebirth in a higher caste of initiated beings. Yoga here is not liberation but redemption-by-domination, with the brown body as both threat and resource.

Home’s relentless critique dismantles the pretense that figures like Yeats-Brown were accidental mystics. Their attraction to yoga was never about genuine engagement with Indian philosophy but about accessing a symbolic grammar of discipline, hierarchy, and transcendence that could be repurposed for the fascist imaginary. The guru-disciple relationship, as embraced by both Fuller and Yeats-Brown, was not just spiritual pedagogy, it was a model for authoritarian social organisation. The yogic ideal of surrender to the guru mapped neatly onto fascist demands for obedience to the leader, allowing Eastern spirituality to be retooled as a mechanism of Western political control. What Home makes clear is that these figures did not merely misunderstand yoga, they instrumentalised it, hollowed it out, and filled it with fascist content. The result was a hybrid spiritual-political formation: a racist mysticism clothed in asanas and mantras, a theology of power masquerading as spiritual enlightenment.

And disturbingly, this hybrid formation did not die with the collapse of interwar fascism. Fuller’s writings remained in circulation; Yeats-Brown’s memoirs lived on in Hollywood myth; Pierre Bernard’s pseudo-tantric ashrams evolved into upscale yoga studios. The fascist potential of yoga and its capacity to organise bodies, to demand submission, to aestheticise hierarchy was not extinguished but laundered into the cultural mainstream. Home’s argument, then, is not merely historical, it is, as always, diagnostic. The same symbolic operations are still at work today in the global wellness industry’s racialised idealisation of “authentic” yoga, its commodification of inner peace through bodily discipline, and its quiet reproduction of colonial hierarchies through cultural appropriation and spiritual elitism. (The same could equally be said of many strands of the psychedelic movement and its male gurus).

Indeed, Home insists that the pseudo-universalism of yoga’s neoliberal packaging and the fantasy that anyone, regardless of background, can ‘access’ enlightenment through individual effort echoes the fascist cult of self-transcendence. Both erase history, both promise a purified subject, and both deny the structural conditions that make such purification impossible. In the world of Yeats-Brown and Fuller, this purification was racial and spiritual; in the world of Lululemon and Instagram yogis, it is aesthetic and psychological but the ideological gesture is the same. This is the continuity Home traces: from the swastika-bearing Desperates of Rijeka to the manicured tranquility of the Western yoga studio. Behind both lies the same desire to transcend the democratic self, to be reborn in a higher form, to belong to a spiritual elite that escapes the mess of politics. This is not the yoga of the Bhagavad Gita or Patanjali, but the yoga of Evola, Keller, Fuller, and Yeats-Brown: a yoga of power, purity, and myth. It is, as Home concludes, a spiritual technology of fascism rebranded, rehabilitated, and still very much alive.

Yeats-Brown’s peculiar fusion of racial mysticism and physical culture, invocation of Indo-European linguistics and Aryan kinship to ground yoga in a shared ‘racial inheritance’ was not uncommon among the Western esoteric milieu in the interwar period. But as Home makes clear Yeats-Brown’s version was especially charged, given his open alignment with fascism and racial nationalism. In his hands, yoga became not just a method of health or spiritual refinement, but a tool of civilisational resurgence, intimately bound up with visions of imperial renewal and racial destiny. In this respect, his teachings echoed the contemporaneous project of Nazi Germany’s appropriation of Indo-European myth, including the swastika, which Yeats-Brown casually repurposed as the name of a meditation pose. The symbolic convergence of fascism and yoga was not merely accidental: it reflected an ideological strategy to sacralise war, hierarchy, and bodily discipline through ‘Eastern’ metaphysics. That this hybridised, politicized version of yoga gained traction, at least temporarily, is a testament to the way spiritual practices can be distorted to serve reactionary goals.

Yeats-Brown was not a systematic thinker, but his scattered pronouncements make it clear that he imagined yoga not as a universal path to liberation but as a means of cultivating a warrior elite. His vision was anti-modern in sentiment but modernist in method, invoking ancient wisdom while relying on popular media to spread his message. The fact that his yoga writings appeared in glossy women’s magazines and tabloids, even as he praised the spiritual purification of war and attended fascist rallies, points to a deep dissonance between medium and message. The yoga he promoted in Cosmopolitan, stripped down to headstands and breathing for beauty and mental clarity, had little to do with the fascist mysticism expressed in Dogs of War or Yoga Explained. Yet these disparate fragments were held together by a single rhetorical gesture: the belief that modern malaise could be overcome through disciplined embodiment, spiritual regeneration, and a return to primordial roots. Sounds familiar?

This is why Home’s book is so pertinent. This is the sort of rubbish that appeals across the whole spectrum of our culture. Interestingly, Home points out that though this racialised mysticism was a key element in Yeats-Brown’s popular appeal in the early 1930s, it also proved his undoing. As political tensions in Britain escalated, and public support for fascism wavered, Yeats-Brown’s alignment with Mosley and his ideological extremism cost him both readers and professional standing. His dismissal from Everyman after only seven issues was a clear indication that the fascist ‘spiritual’ synthesis he offered was no longer palatable to mainstream audiences. Nor could he repackage himself successfully for other markets. His attempts to revive interest in yoga through instructional books and lightweight journalism failed to recapture the success of Bengal Lancer, in part because the political undercurrents of his vision had become too obvious, and in part because his writing lacked the coherence and humility expected of a spiritual teacher. Even so, as Home makes clear, Yeats-Brown’s contribution to the globalisation of yoga remains significant, and troubling. He was among the first to market yoga to mass Western audiences in explicitly physical and self-help terms.

His books, columns, and photographs helped recode yoga from a rigorous Indian spiritual discipline into a lifestyle choice accessible to middle-class readers in search of health and self-mastery. He did so through a synthesis of militarism, Orientalism, and esotericism, prefiguring later New Age appropriations but with a far darker ideological cast. If his vision ultimately failed to endure in its original form, it nonetheless laid groundwork for the commodification and racial encoding of yoga that would persist in more subtle ways throughout the twentieth century. That his image endures, scrawny, upside down, making pained claims to spiritual insight, is not just an odd footnote in the history of yoga’s Westward journey, but a revealing symptom of its entanglement with the politics of race, empire, and modernity.

Home shows how this legacy of far-right esotericism, born in the crucible of interwar fascism and occult experimentation, evolved not through scholarly engagement or political tract but through the ambient, affective channels of culture - music, fashion, symbolism. Figures like Evola and Devi, whose arcane tomes might seem marginal in academic discourse, found a second life in the aesthetics of alienation and rebellion. The neofolk and martial industrial scenes, with their flirtations with pagan imagery, ritualized performances, and themes of spiritual elitism, offered a gateway for fascist metaphysics to slip into subcultural consciousness under the guise of arcane mystery or transgressive chic. That these movements rarely involved serious reading of Evola or Devi is beside the point; their names became talismans, markers of initiation into a darker, “higher” form of knowing, a gnostic fascism that traded in resonance rather than reason. The fact that Evola never practiced yoga but wrote as though he embodied its deepest truths only underscores the performative nature of fascist esotericism. It was never about lived experience, but about the projection of aristocratic spiritual authority, of mastery over the profane’ world. His warrior yogi was not a practitioner but an archetype, designed to discipline the spirit into conformity with an imagined cosmic hierarchy. In this sense, Evola’s yoga is not a misreading of tantra but a deliberate ideological appropriation, a metaphysical architecture built to justify domination of the self, of others and of entire peoples.

Savitri Devi took this metaphysics one step further, fusing Hitlerism with Hindu bhakti in a grotesque theological fusion that made the Führer a divine avatar. Her writings, while eccentric to the point of absurdity, reveal the extent to which spiritual frameworks can be made to serve genocidal politics. Her vision of a ‘new dharma’ based on caste, racial purity, and apocalyptic redemption shows how the language of karma, yoga, and Hindu eschatology could be twisted into tools of fascist myth-making. Devi’s position as a white European woman seeking spiritual legitimacy in India also points to a deeper dynamic in the history of modern yoga: the colonial-romantic fantasy of spiritual East meeting militant West. In juxtaposing these figures, Home does not simply condemn them for ideological aberration. Rather, he reveals a structural continuity between fascist esotericism and the broader Western encounter with yoga and tantra, an encounter often shaped by projection, appropriation, and racial hierarchy.

The same impulses that drew Yeats-Brown to Pierre Bernard, or Himmler to the Bhagavad Gita, are not so distant from those that animate certain corners of contemporary yoga culture: the quest for purity, the myth of ancient wisdom, the desire for mastery over body and soul. Home’s excavation of these histories challenges the comforting liberal fiction of yoga as an inherently progressive or apolitical practice. It reminds us that spirituality, far from being a realm apart from politics, is deeply entangled in the same ideological battles that shape our histories and futures. The sanitised, commodified yoga of today may seem worlds away from Himmler’s esoteric fascism or Evola’s warrior metaphysics, but the genealogical lines persist and are often hidden in plain sight. This is perhaps the most unsettling lesson of Home’s work: that yoga’s global diffusion was never simply a story of peaceful transmission or cultural exchange. It was also a story of power, of how ancient practices were co-opted, racialised, militarised, and packaged to serve the spiritual needs of empire, fascism, and, eventually, neoliberal self-optimisation. The yoga mat, like the swastika before it, can become a site of projection, where fantasies of discipline, transcendence, and racial hierarchy play themselves out under the banner of health and freedom.

Home’s investigation of early Western yoga figures, from Savitri Devi’s mystical fascism to Harvey Day’s occult populism, reveals not only how yoga was imported, but how it was reinvented to serve a variety of ideological, aesthetic, and commercial ends. The persistent throughline is not a coherent spiritual tradition but rather a fragmented collage of esotericism, race mysticism, theatricality, and opportunism, adapted to Western anxieties and desires. Fascist aesthetics subtly embedded in musical subcultures, pseudo-scientific miracle claims made by self-styled gurus, and the sanitized glamour of celebrity yoga instruction all function as expressions of deeper cultural currents and an ongoing search for purity, transcendence, and authority in an uncertain world. What emerges is a portrait of yoga in the West as a vessel, one into which different groups have poured contradictory meanings. For some, yoga became a tool for white spiritual nationalism; for others, a lucrative performance of wellness; and for still others, a vague conduit for cosmic mystery. But in all these variations, the integrity of yoga’s philosophical and ethical roots was often subordinated to the spectacle of transformation, whether physical, political, or metaphysical. The myth of a mystical East, already distorted through colonial lenses, was further contorted into a mirror of Western ideological fixations: racial superiority, esoteric elitism, and the commodification of self-mastery.

Home tells a nuanced story, showing how the convergence of yoga with fascist-inflected occultism was not always explicit, yet the ideological residue lingers in the language of ‘awakening,’ ‘purification,’ and ‘hidden wisdom’ that saturates wellness discourse. For me this language is always a trigger warning. Home’s fascinating and brilliant book helps excavate the reasons why this is so. Figures like Day and Devi, though dissimilar in political temperament, tapped into the same wellspring of Orientalist longing and esoteric projection. Both contributed to a wider ecosystem of spiritualised irrationalism, a domain where truth was less important than resonance, lineage was less important than aura, and historical accuracy gave way to personal mythology.

Through reading Home we can see how all this is fertile ground for the kind of syncretic but ideologically charged formations that persist in new forms today, whether in nationalist yoga festivals in India, conspiracy-laced wellness communities in the U.S., or rune-based movement practices quietly disseminated under the banner of ‘ancestral spirituality’ at Glastonbury. Each iteration extends the shadow of earlier figures who merged posture and propaganda, breath and blood, devotion and delusion. The seeming innocuousness of many modern yoga practices cannot fully mask this history, nor the continuing attraction of mystified, depoliticised, or racially essentialist narratives cloaked in the language of inner peace. Far from being marginal or freakish, these stories illustrate how easily spiritual practice can be co-opted into reactionary cultural projects.

The Western yoga movement, in its early incarnations, was not merely naïve or misinformed; it was often structured by fantasies of mastery over the body, the self, and the Other. As such, revisiting this history is not a matter of discrediting yoga per se, but of confronting the deep entanglement of wellness culture with the ideological debris of empire, esotericism, and exclusion. This recognition complicates any notion of Western yoga as a clean or linear inheritance of Indian wisdom. Instead, what emerges is a hybrid tradition, cobbled together from uneven parts: post-Victorian spiritualism, racial science, European occult revivalism, and scattered fragments of Indian practice, all repurposed for Western appetites.

Harvey Day, in this sense, is less an outlier than a crystallisation of the mid-century milieu in which yoga was transformed into something both familiar and alien, a self-help system cloaked in Oriental mystique, promising psychic power, immortality, and inner peace, but built on shaky ideological ground. This ideological instability became particularly visible as Western yoga matured into a broader wellness culture. What was once fringe, promises of levitation, psychic expansion, or immortality and all that junk has not entirely disappeared but been reframed in subtler forms: biohacking, detox cleanses, chakra balancing apps, or yogic business coaching. The same market logic and spiritual opportunism that drove Day to repackage occultist lore for postwar readers now underpins a global industry where yoga serves as a vehicle for self-branding, emotional regulation, and conspicuous virtue.

The continuity lies not in the techniques themselves, but in the persistent exploitation of yoga’s symbolic capital for Western psychological and social needs. Indeed, yoga’s absorption into consumer culture echoes the earlier pattern of symbolic abstraction: just as Charles Wase and Felix Guyot reduced spiritual traditions to interchangeable psychic tools, today’s wellness influencers abstract yoga into lifestyle aesthetics stripped of context. This secular mysticism finds its roots in the same syncretic logic that saw Guyot equate esoteric Catholicism and Freemasonry with yoga, or Day echoing Nazi-tinted Aryan myths while claiming moral opposition to fascism. The thread that binds them is not belief but utility, in what works, what sells, what feels empowering irrespective of historical accuracy or ethical coherence.

Such practices, while appearing benign or even liberatory, carry within them the residues of their formation: colonial fantasy, spiritual appropriation, and ideological distortion. Even as yoga in the West becomes more inclusive and professionalised, these buried lineages persist, often unnoticed. The forms may change, but the structures of myth-making, ideological camouflage, and symbolic commodification remain intact. They are what allow an image of yoga as peaceful and progressive to coexist with undercurrents of reactionary nationalism, racial superiority, and spiritual elitism, a contradiction embedded from the outset, as Home shows, by figures like Day, Guyot, and Wase.

To critically engage with modern yoga, then, requires more than recovering its Indian roots; it demands tracing the entire palimpsest of influences, especially the distorted and troubling ones. It involves understanding how fascist, occult, and racial ideologies became embedded in yoga’s Western image not only through bad actors but through structural tendencies in Western spiritual seeking itself and its hunger for mastery, transcendence, and esoteric authenticity. That figures like Day could unwittingly act as vectors for these ideas is a cautionary tale about the seductive ease with which spiritual practices can become ideological vessels. Home's genealogy also forces a reconsideration of what it means to ‘decolonise’ yoga. It is not merely a matter of emphasizing Sanskrit terms, citing Indian teachers, or reinstating philosophical texts, but rather confronting the full scope of yoga’s entanglement with modernity’s darker impulses. This includes interrogating how yoga became a carrier for white supremacist mythologies, how it was recoded into bourgeois self-improvement, and how it continues to reflect the neoliberal imperative of self-regulation under the guise of liberation.

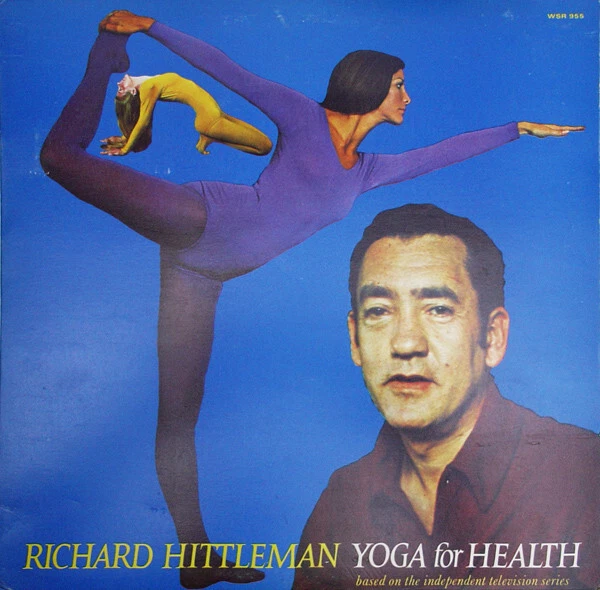

In this light, Hittleman, a figure Home discusses at length, exemplifies the fusion of yoga with mass-market motivational culture, in which Eastern spiritual language becomes a performance deployed to sanctify personal ambition, discipline, and economic self-optimisation. His televised yoga programs, books, and media appearances built a persona grounded less in lineage or depth of understanding than in charisma and accessibility. Yoga, in his presentation, became something to be consumed and flattened into a series of palatable life lessons, detached from its Indian philosophical roots, and repackaged to fit American ideals of success, control, and positivity. His calming voice and tidy mantras promised serenity not through renunciation, ethical inquiry, or devotion, but through repetition and personal branding. This domesticated yoga, a hybrid of pop psychology, white middle-class values, and vague spirituality, helped transform what had once been a countercultural or mystical import into an everyday wellness routine. But it also carried troubling implications. By framing yoga as a therapeutic tool for managing stress and enhancing productivity, Hittleman and others redirected its orientation away from liberation (moksha) or transcendence, toward conformity with capitalist norms.

The subtle violence here lies not in overt authoritarianism, as with a character like Lee-Richardson, but in yoga’s quiet assimilation into the corporate and domestic order: a de-radicalised spiritual practice tailored to fit neatly between morning meetings and evening cocktails. This transformation resonates with Home’s broader thesis: that Western yoga’s emergence was rarely a pure or innocent borrowing. Instead, it took root within, and was reshaped by, historically contingent structures of power, commerce, and ideology. Yoga was not simply misunderstood; it was actively retooled to serve the psychological, political, and economic needs of its new hosts. At times this meant fusing yoga with esotericism and fascist myth (as in Lee-Richardson); at others, it meant collapsing its complexity into digestible slogans and consumable exercises (as in Hittleman). In either case, the result was a profound distortion.

The case of Margot Fonteyn further complicates this narrative by showing how yoga was marketed through celebrity appeal, aesthetic glamour, and upper-class sophistication. Fonteyn’s embrace of yoga in later life, along with her public endorsements and magazine features, helped sanitise and elevate yoga’s image, aligning it with elegance, refinement, and bodily discipline. But this too involved a certain flattening. Yoga became not a philosophical path but a graceful supplement to ballet and beauty, legitimised through the aura of fame and cultural capital. Here, the orientalism that underpinned much of early Western yoga remains operative only now reimagined through the language of elite taste and bodily grace. Such shifts reveal yoga’s malleability, but also its vulnerability. Removed from its ethical frameworks, philosophical contexts, and devotional roots, yoga in the West became a mirror reflecting whatever fantasies or anxieties predominated in a given era: post-war occult revival, Cold War discipline, New Age individualism, neoliberal self-care.

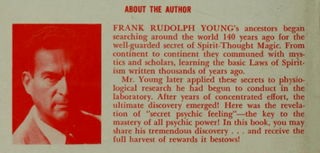

As Home’s critique makes clear, this flexibility is not without cost. What masquerades as timeless wisdom conceals histories of appropriation, racialisation, commercialization, and ideological compromise. Yet the persistence of these figures and their ideas in contemporary yoga discourse suggests that the genealogical threads uncovered in this study are not merely historical curiosities. They inform the very structure of how yoga is taught, marketed, and practiced today. The continued emphasis on asanas over ethical conduct, the obsession with results (be they psychic, physical, or financial), and the silence around yoga’s colonial entanglements all testify to a legacy still unfolding. Home uses as a case study the example of Frank Rudolph Young to illustrate all this in our contemporary fucked over context. He shows that contradictions do not seem to diminish the appeal of Yoga for certain audiences. In fact, the lack of coherence may enhance its function as a fantasy structure: a protean blend of occultism, pseudoscience, male empowerment, and spiritual elitism that invites readers to project their own desires onto the text.

Home’s analysis reveals that in the case of Young, his yoga is not about inner peace or liberation, but about conquest, of the self, of women, of the social world. It offers a blueprint for an idealised masculinity rooted in control, secrecy, and exceptionalism, resonating with postwar anxieties about gender, power, and identity. As Home intends us to realize, the likes of Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson and Donald Trump rise like idiot spirits from all this. This underlying structure connects to broader authoritarian patterns. The recurring themes of secret knowledge, rigid discipline, and unchallengeable authority mirror fascist ideologies in which purity, strength, and submission to hierarchical order are paramount. As in the case of Young, Yoga, in his hands, becomes an esoteric fascism: not a path to liberation from the ego, but a glorification of the ego as supreme, sovereign, and untouchable. The very language of his books with phrases like “Unconquerable,” “Master,” “Invincible Eye” all reveal a fantasy of the self as fortress, defended against uncertainty, vulnerability, and relational dependence. This reimagining of yoga also dovetails with a deeper critique of modern spiritual capitalism.

Figures like Young, Lee-Richardson, and Hittleman each repurpose yoga into a commodified system of personal advancement, but the ends they promise differ. Where Hittleman sells calm and faith, Lee-Richardson markets mystery and access, Young offers domination. Their shared reliance on secrecy, exclusivity, and unverifiable claims points to a pseudo-religious business model, one that thrives on both anxiety and aspiration. As Home shows, this model not only strips yoga of its historical richness but reconfigures it into a mechanism for social sorting, of sorting the credulous from the skeptical, the disciplined from the lazy, the ‘superior’ from the masses. What emerges is a powerful account of how the global yoga industry, far from being a benign site of wellness and cultural exchange, has historically been entangled with ideological projects that range from colonial mimicry to authoritarian self-fashioning. Home’s interventions are never simply academic corrections to popular myths; they are political. They force us to see that what passes for spiritual or therapeutic in contemporary yoga often reproduces power hierarchies, racialised fantasies, and masculinist myths of mastery.

The image of the solitary white yogi, self-possessed and triumphant, is not an innocent figure but one shaped by histories of empire, patriarchy, and capitalist spectacle. This realisation complicates any attempt to recover an ‘authentic’ yoga tradition. The cultural contaminations and ideological distortions revealed in Home’s study are not superficial blemishes on a pristine tradition but are constitutive of how yoga has been made intelligible and desirable in the modern West. Yoga’s ability to invoke diverse, superficially treated cultural motifs functions as a kind of spiritual cosplay, designed to dazzle and disarm rather than to deepen understanding or foster genuine connection. This kaleidoscopic borrowing dilutes the very traditions it claims to honor, transforming rich, complex systems into commodities for easy consumption. Home shows how syncretic pastiches can gain footholds well beyond their niche origins. The fact that Young’s work finds indirect expression in mainstream media, even if only as a source of humor or critique, points to the porous boundaries between fringe beliefs and popular consciousness, boundaries that are increasingly being breached. Beneath the caricature lies a sobering truth: these ideas resonate because they tap into real emotional and existential needs, however distorted their solutions may be. The self-help marketplace becomes a fertile ground for exploitation, where the vulnerable are sold not clarity or healing, but illusion and control.

Home shows that Young’s legacy serves as a stark warning about the risks inherent in embracing occult claims without critical scrutiny. His blend of narcissism, cultural appropriation, and pseudo-scientific babble is not merely harmless eccentricity; it perpetuates harmful myths about power, gender, and knowledge. Even where some of his physical practices offer genuine benefits, they are embedded within an overarching framework that privileges dominance and fantasy over humility and genuine growth. When compared with contemporary figures like Tate, the parallels become clear: both speak to those hungry for simple, potent solutions to complex problems, promising mastery through carefully curated personas of hyper-masculine dominance. The rituals, postures, and performative confidence they champion serve a dual purpose: fostering personal empowerment while reinforcing systems of control, particularly over women. The message is unambiguous - true strength demands the suppression of vulnerability and the projection of uncompromising authority. What distinguishes today’s digital hustlers is the scale and velocity of their influence. Social media platforms amplify their reach exponentially, generating rapid feedback loops that can intensify radicalisation and communal reinforcement. Yet the underlying architecture, the promise of secret knowledge and social dominance sold through performative masculinity, remains fundamentally unchanged from Young’s mid-century mail-order operations.

Home’s engagement with figures like Young offers vital insight into how the surface allure of self-help and fitness culture can conceal a more insidious agenda: the propagation of reactionary, often misogynistic ideologies disguised as personal transformation. Recognizing this historical continuity is crucial for critically navigating both past and present wellness landscapes. The persistence of these figures, despite their glaring flaws and exploitative strategies, signals a broader cultural susceptibility to simplified narratives of empowerment and healing. In an increasingly fragmented and uncertain world, the appeal of secret wisdom and clear-cut mastery is undeniable. Postural practices, therefore, become contested cultural terrains where spiritual commodification intersects with political and ideological struggles. The intensification of commodification via digital capitalism only magnifies these challenges. Online spaces facilitate the rapid spread of both authentic teachings and toxic ideologies, creating echo chambers that nurture misinformation and foster cult-like devotion with alarming speed.

Home’s modern story of postural practice within Yoga culture thus emerges as a cautionary parable: the promise of effortless transformation or access to hidden power conceals exploitation and ideological manipulation. Peeling back the glossy veneer demands critical inquiry into who truly benefits and who pays the price when wellness becomes entangled with authority and myth-making. Home’s examination of yoga fascism as presented through figures like Frank Rudolph Young offers a powerful lens for understanding the complex, often contradictory nature of contemporary fascism. Home’s examination of Young’s ‘yoga fascism’ model highlights the troubling intersection between therapeutic culture and authoritarian politics. The rise of therapised well-being where emotional vulnerability and self-care become commodified can paradoxically feed into fascist dynamics when it becomes entangled with narcissism, conspiracy thinking, and a siege mentality.

Movements like anti-vaccination activism and conspiracy theories emerge not simply from ignorance but from a deep mistrust of institutional authority coupled with a desire for secret knowledge and personal sovereignty. These features echo the same patterns of occultism and pseudo-science found in Young’s oeuvre, revealing how fascist ideology repackages itself through the contemporary wellness-industrial complex. The spectacle of ‘therapeutic fascism’ reaches its apex in figures like Donald Trump, whose political persona is constructed through a performative blend of grievance, dominance, and pseudo-therapeutic appeals to individual empowerment. Trump’s rise illustrates how fascism in the digital age mobilises not just traditional nationalist and racial anxieties, but also taps into the cultural currency of self-help, victimhood, and spectacle.

The influencer and guru phenomena, exemplified on the right by Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate and on the left by Judith Butler and Zizek, demonstrate the bifurcated but parallel ways that cultural authority is built around charismatic individuals who promise access to hidden truths, social mastery, or identity liberation, often reduced to social media-ready soundbites and viral moments. TikTok culture amplifies this dynamic further, accelerating narcissism and fragmenting attention spans, while simultaneously turning health and wellness into toxic commodities where identity, status, and political affiliation are performed as brand loyalty.

Home’s analysis is essential because it traces these connections with rigor and nuance, showing how the commodification of spiritual and physical practices cannot be disentangled from reactionary politics, misogyny, and authoritarian myth-making. By unpacking the genealogy of ‘yoga fascism,’ the book exposes how fascism is not merely a set of outdated political doctrines but a mutable cultural phenomenon that reinvents itself through contemporary consumerism, media, and therapeutic discourse. It challenges readers to recognize that beneath the veneer of wellness and self-improvement lies a potent mechanism for spreading exclusionary and hierarchical ideologies, often under the guise of healing and empowerment. In an era where fascist aesthetics and ideas seep into everyday life via social media, fitness culture, and the wellness industry, Home provides a critical framework for understanding how these forces operate, why they appeal, and how they can be resisted.

This makes the book not just an academic intervention but a necessary tool for anyone seeking to navigate the cultural battlegrounds of the 21st century with clarity, critical insight, and a commitment to genuine liberation rather than illusory mastery. As ever, Stewart Home has written a startlingly prescient and necessary book giving us a geography of our strange and terrifying cultural and political landscape. BUY IT!