Playroom (8): Nosferatu

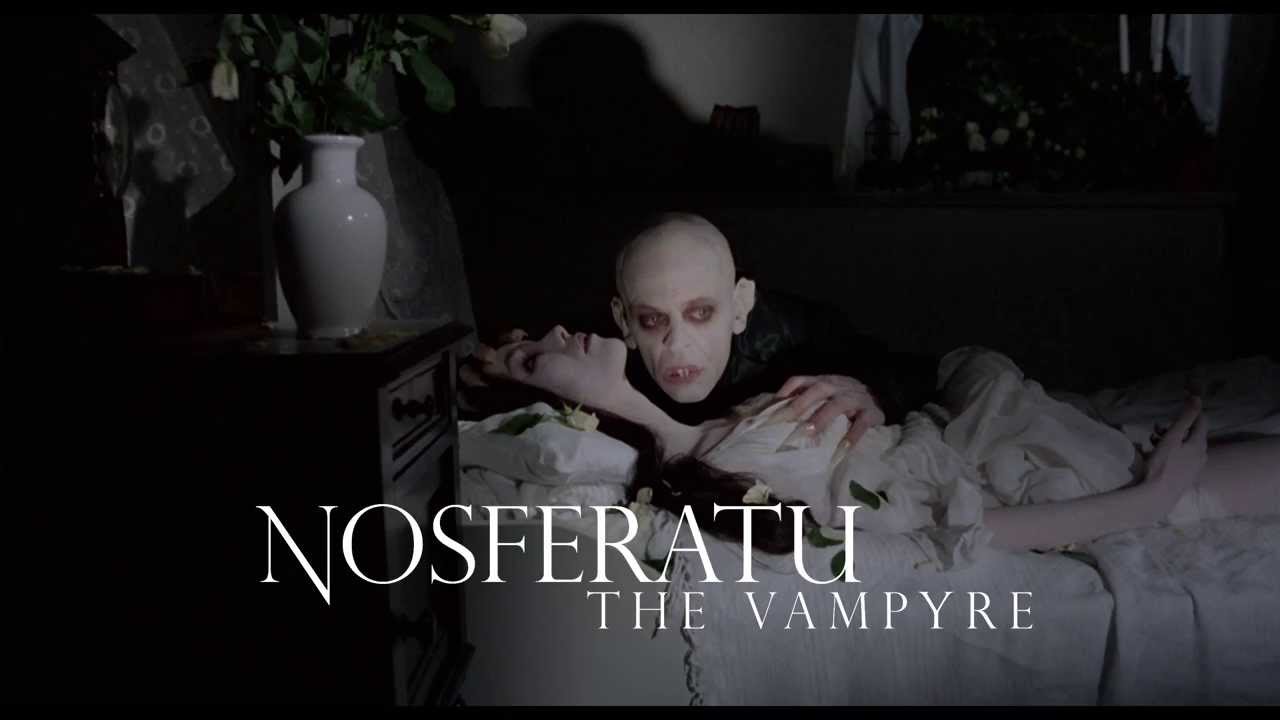

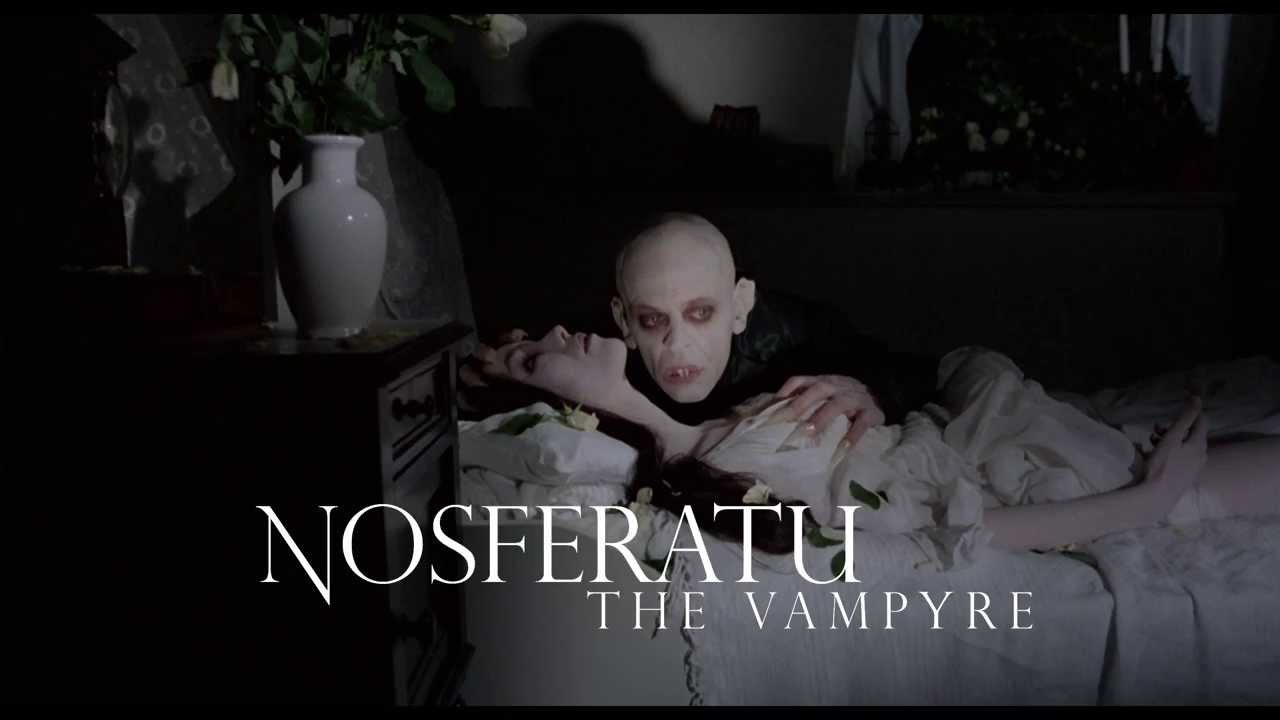

Nosferatu the Vampyre: Directed by Werner Herzog

A film that accepts a kind of waiting that is older than explanation. The screen learns to breathe at the speed of sleep. A face that is not yet a person appears like a memory rising through water. The air has a winter clarity even when the light is summer. A town sits by the sea as if it had grown tired of being seen and had decided to be a picture of itself. A man departs from this town at the request of another man whose confidence will soon be the most fragile thing in the frame. He rides toward a mountain and enters a country that behaves like a sentence that was completed long ago and has been waiting ever since to be read again. A ship leaves a harbour with the energy of a plan that cannot admit to itself what it intends. Rats are carried across a threshold. A woman waits in a room where the curtains know more than the furniture. The film is an old tale told with an exactness that finds the present inside the past and that refuses to let either claim priority over the other.

The first image that will not disappear is not a landscape and not a person. It is a mouth that never opened and eyes that no longer attend to the world. They belong to skulls that still wear their skin. The camera shows them with a tenderness that makes refusal the only honest response. They are arranged in an order that hints at ritual and museum at once. They appear to be listening. We are made to understand that what follows occurs under their gaze. The film takes this arrangement as its law. It proceeds in a register where bodies are already images and images are already bodies that have been relieved of their heat.

A town beside water supplies the first measure of ordinary life. Streets remember honest work, windows keep an eye on the slow commerce of boats and carts. A clerk bends over a desk and counts out the means by which another person will be sent into danger without the word danger being spoken. He smiles because smiling turns contract into conversation. His wife moves through rooms with the calm of one who has learned that the world is not a series of events but a pressure that changes the temperature of a day. She has a face that the camera regards the way a lamp regards a white wall. It places light there and waits for the light to return with something the lamp did not know it had in reserve.

The journey toward the castle is the education of a man who did not believe he needed one. Mountains shift into a ladder. Forests are curtains that don't part because they drape walls not doors nor windows. Winds scrawl a single sentence on every surface. Villagers who know what the traveller does not know give him what they can. Their gifts do not prevent the lesson. The lesson is that distance is not measured by miles and that courtesy cannot protect a person from a hospitality arranged by time. At an inn where the traveller wishes to be a guest and not a figure in a legend, a book appears with the promise of knowledge and the threat of ending the need for it. He goes on in the morning with a stubborn cheer that is already the mask of a fear he cannot shape.

The castle waits. The walls suffer no history of siege and yet they are a record of defeat. Doors open without hands. A table is laid with regard only for the person who will sit within reach of the host. The host arrives as if darkness had been placed inside a man and asked to behave. His body has learned the gravity of the place where he lives. He moves as if each step discovers the angle of a room that could not be found while the room was empty. His mouth speaks in a tone that remembers politeness but has forgotten what politeness was for. He declares a need that cannot be named and in naming it anyway he becomes almost gentle. The camera refuses to make him an emblem of what we know already. It sits with the face and allows the face to be a fact among other facts.

There is a table talk in which nourishment becomes theatre. Meat looks like a memory of a life in another season. Bread is broken with an elegance that has no appetite nor sustaining rite. The guest eats because he is a guest and the host watches because watching is how he eats. To complain that the scene is slow is to confess that one has not yet learned the time in which this house gives movement permission. The film holds the scene to its pace until the pace becomes the measure of other scenes and of the lives that will either accept or resist it.

The lover in the town begins to listen at night for a sound that would tell her the sea has brought him back. She hears only the city rehearsing its small errands, the bell that helps the hour remember itself, the soft conversation of the wind with a curtain that was not placed in a window to converse. She sleeps and sees a picture that the film avoids dramatising. It gives her the right to see rather than the pleasure of being right. When morning breaks the room returns to neutrality. That neutrality is the climate in which she will keep the town alive for as long as it can be kept alive.

The seduction in the castle is arranged like a ceremony where the celebrants no longer believe. The seducer confesses that he has nothing to offer that will survive the hour and the seduced repeats words that promise a future she does not intend to honour. This would be trivial if the film allowed it to be a play of victory and defeat. It is not trivial because the host is a man who is tired of his own authority. He knows the cost of his appetite and he is not reassured by payment. His visitor is a man whose name will be stripped from him without the comfort of being told what the new one is. When dawn arrives the castle is ashamed of itself and shows this by appearing exactly as it did before the men entered it.

The ship bears the town’s future inside a hold that prefers to remain closed. A captain learns that rules and ropes cannot keep the sea from delivering what the land has summoned. The voyage is shown in a few strokes that leave the mind to complete the scene. The completion is not fantasy. It is labour that the film asks of the viewer as payment for a kind of knowledge that cannot be handed to anyone. When the ship glides into harbour without the noise by which ships announce their arrival, the town understands that silence is sometimes a more exact sound than the tolling bell.

Rats arrive in a number that cannot be counted. They are not the carriers of a metaphor. They are the form that numbers take when life has decided to exceed measurement. They slide from crates as if breached from wounded wombs. They run where they wish because there is no longer any reason to forbid them. Their movement alters the grammar of streets. People step aside for them without knowing that they have learned a new courtesy in a single minute. The film respects them with a camera that does not hurry or recoil. They are granted the same attention given to faces and to clouds.

A dinner is laid in a square. The table is long and the tablecloth is elegant and the plates are handsome and the food is abundant. There are flowers. There is wine. This is a gesture not of defiance and not of surrender but of equality. The city addresses the hour in the only language that has ever allowed it to be dignified. It eats together and understands that togetherness is the one appetite a plague cannot injure. A couple dances for the length of a tune. The tune becomes the town’s last plan. The film watches without pity and without approval. It keeps the scene at the distance required for fidelity.

The lover speaks to the stranger at last, and the room where they meet has the clarity of a sentence that has been pared to the bone. She offers herself in a manner that is neither sacrifice nor seduction. She has learned by anticipation what the stranger has learned by exhaustion, that desire without limit is poverty and that life without appetite is another form of hunger. The scene is not a triumph. It is the release of a pressure no one else could bear. Light is used like a hand on a fevered brow. The camera refuses to move closer at the moment when most films would ask us to collapse into music. It allows the act of her hand to be the measure of itself. When morning comes the room is a room again and the town is a town that cannot claim a miracle.

A doctor has been kept nearby in order to prove that reason remains and to expose the limits of its jurisdiction. He asserts because assertion is the duty of his office. He is fooled because the world cannot be argued with while it is changing its terms. He declares a plan and is ridiculed by a city that has given itself the right to die on its own schedule. He will live to watch others depart. The film keeps him within reach because it knows that good intentions are also part of the plague.

The husband returns and his face has been altered by contact with a place that exists beyond the weather report. The town knows this before he does. He moves in a new time that obliges him to stand still. When he sits he looks like a speeding object that has been captured by a camera that used a faster shutter. The transformation that follows is shown with the reserve the film uses whenever it allows the body to become the register of what the world has written on it. Teeth appear at the edge of a mouth that had not been made for them. The gaze becomes an instrument rather than a relation. He is no longer free to hesitate. What remains for him is certainty without content. He will go where the movement sends him.

The town empties itself with the order of a rehearsal. Bells ring as if they were thinking clearly. Officials write as if they had decided that sentences might still differentiate between cases. A procession appears and behaves as if it could still be seen by an authority that would be familiar with incense and with evidence. The film lets this pass through the square and into an alley where the distinction between theatre and procedure becomes irrelevant. Children run. A cart carries flour that will be eaten by those who no longer believe in tomorrow. The rats express a joy that is indistinguishable from work.

Rooms begin to turn back into the shapes they had before people learned to fill them with plans. Beds are made for sleep that will not be ended by day. Tables are laid for meals that will be forgotten while being eaten. Windows are closed not to keep out the air but to permit the daylight to become a refracted object on the sill. The camera moves through these spaces with the attention that the day deserves when it has ceased to be a path and has become a kind of presence. In such rooms the light behaves like a word that cannot be translated and that is nevertheless understood at once.

The stranger who began as a force begins to disappear into a kind of pity. The pity is not sentimental. It is the recognition that a life can be long enough to injure its owner. He stands at a window and looks at nothing because nothing has become a place where he can rest. He approaches her body not with triumph but with relief. The film refuses to cleanse him and refuses to curse him. It keeps him where he was first placed, in the position of one whose need has made him both guilty and obvious. The obviousness is not a verdict. It is the removal of mystery for the sake of another kind of secret.

A room fills with men who have decided that the hour permits them to rescue the order they remember by taking a life they will not understand. They enter with things that will be instruments for a ceremony rather than tools for a solution. They are not cruel. They are not brave. They are obedient to a story that has held them since childhood and that has not been revised by a night of plague rats and plague bells. The film gives them their scene and releases them from it without dwelling on consequence. They are part of the picture in the way a fence is part of a field. It marks a limit that can be crossed once and then no longer.

The ending is not an end. A horse moves across sand that accepts it and keeps no trace. A rider carries a certainty that does not belong to him. The camera stays with this pair long enough for the image to overtake its own meaning and become merely the image it is. The town remains behind like a coin left in a room that will never be opened again. The sea continues its polite quarrel with the land. The sky tries another colour and decides against it. The film has not closed anything. It has permitted the viewer to stand in a time where closure is both childish and cruel.

Because the film is a reply to another film that has been looked at until it discovered that it could look back, one might expect quotation to be the principal means of relation. Quotation occurs, but it is not the engine of the work. The reply is carried in the difference of breath and in the decision to attend to bodies as if history were visible in clavicles and in the angle of a wrist. Light is used as a way of writing rather than as a way of revealing. Music is allowed like a thought that returns when speech remembers that it has excluded tenderness. The score does not insist on its power. It stays under the skin and lets the images take the weight.

The face of the woman becomes the film’s truth. She is the one place that can still be entered without lying. She is asked to be prudent and to be faithful and to be brave and she refuses all three when refusal becomes the only form of responsibility left to her. The camera knows how to place her so that her presence fills a room without claiming it. When she speaks to the stranger she speaks without doctrine. She offers him the rest that belongs to the living and accepts the consequence that belongs to the dead. This is not martyrdom and not victory. It is the equality that desire confers when it is moved beyond appetite and beyond purity into the quiet of contact.

There are shots of water and of stone that would be ornamental if the film had not long since trained us to take them as statements. Water closes its surface over a shape that does not concern it. Stone accepts a shadow as if it were a child returned from school. A crest of a wave offers itself to the light so that the light can try on another role before night resumes its position. The camera allows these indifferent relations to stand near the scenes of confession and complaint. It refuses to make a hierarchy between them. In this refusal the film discovers its calm.

Because death is never far from the frame one might conclude that the film is cruel. It is not cruel. It is exact. It refuses to move faster than the thing it shows. It refuses to invent a hope that would insult the intelligence of those who must act without it. It refuses to curse those whose fate has asked them to feed on the living. It refuses to flatter those who imagine that they could have loved better if only the world had been kind. Exactness is the only courtesy that remains when stories are asked to touch what cannot be healed by stories.

The town as a space of shared life is allowed one kind of grace and it is visible in the labour by which it continues to practice itself in the absence of guarantees. Letters are carried even when letters have ceased to matter. Doors are opened at the hour and closed at the hour simply because the hour exists. Children chase each other because the body remembers a game that was invented to redeem distance. The film records these gestures without calling them beautiful. Beauty is a word that no longer keeps time here. The images take its place and grow quiet.

The character who sells houses and encourages departures is the engine of the plot and the mirror in which the film regards the vanity of the busy. He is not punished by the story and he is not educated by it. He is removed from the power to name his own movement. A man who profits from keys becomes a man carried by a door that has no lock. The actor finds the posture by which this can be seen without demonstration. He makes stillness persuasive. He allows the loss of identity to behave like the discovery of a task.

The castle returns in memory when the screen no longer shows it. It stands as the image of a form that draws people to itself without promise. Its rooms are the measure of a life ruled by collection rather than by relation. Furniture is a set of positions that the body may take. Pictures are the limits of a thought that has forgotten how to change shape. The host has filled the castle with repetitions that confess an incapacity to begin. This confession is the deepest courtesy he offers and it is the source of the pity that the film grants him without saying so.

A ship arrives and the sequence is given as if the ship were a sentence that has at last found its final clause. Men in the town read the clause differently. Some read it as a warning. Some read it as an opportunity. Some refuse to read because to read would be to begin to grieve before the bell. The film has no interest in dividing these responses into the true and the false. It is concerned with the single act that all will perform, the act of allowing the world to pass through them according to its pattern.

In another film the supernatural would require an apparatus of explanation. Here it is natural. It sits within rooms and seasons like an illness that has forgotten to declare itself. The stranger does not perform tricks. He obeys a need that the camera respects as it would respect a person who drinks water after a long walk. He is the other shape of hunger. The film allows him to make others hungry and allows them to answer with disgust and with surrender. It makes us equal to both without asking us to choose.

The business of mirrors has been much discussed elsewhere. In this telling mirrors behave as they always behave. They return to the room what the room can bear. A face that expects to see itself and sees its absence instead must invent another way to belong. The film does not linger on this invention. It allows absence to be another item of furniture. A space without image becomes a space of complete exposure. The stranger stands inside it and discovers that his solitude has become perfect. The perfection brings no comfort.

When a body is taken from a room the room remains as if it had an obligation to testify. Chairs hold the indentations imposed by weight. A glass on a table knows the shape of a mouth that will not return. A curtain knows how to move the way a skirt once moved and cannot be taught to forget. The film looks at these ordinary allegiances and refuses to raise them to the level of symbol. It trusts the viewer to understand that meaning is not a resource to be spent here. It is a climate the film has prepared for us to breathe.

Another city could have served as the site for this parable. The choice of place is less important than the decision to show a city that believes in its mornings and that will go on believing until the mornings are taken away. The architecture gives the story a grid that seems to promise escape. Lanes converge on a square where people can gather and decide. The gathering occurs. The deciding is an outline traced in the air. It will be enforced by no one. The film records the outline and leaves it to be carried away by the next wind.

The sense that the tale is both ancient and recent rests in the way bodies are filmed. There is no effort to hide that these are modern faces wearing the tasks of an earlier century. A hand draws a curtain with the same movement that would draw a curtain now. A step on a stair sounds as it would sound now. A kiss is awkward in the way kisses are. A hand touches herself intimately as if stroking pale centuries of desire. The effect is not anachronism. It is the refusal to allow time to excuse us from the pressures that stories record. The film makes time the medium rather than the subject. Eros is what time accomplishes.

At intervals the camera lifts its attention to a sky that is neither blessing nor threat. Cloud accumulates like thought. Light discovers a shape in the air and then loses interest. Birds pass by without bringing news. The film places these intervals where they are needed. They are the breaths a tale takes when it has decided not to deliver itself to argument. They are the spaces where the viewer can discover the difference between dread and repose.

The weight of performance rests on three faces. The stranger must carry the fatigue of someone who has lived too long to defend his manner. He does so with a mouth that understands appetite as a reason for sorrow. The traveller must show the transformation of a man into an instrument without making either state an imitation. He does so with the eyes of a person who has been given a task by someone who did not speak. The woman must resist both rescue and surrender without turning either into a lesson. She does so by combining clarity and gentleness until the two become each other. The camera binds these three with a distance that permits misreading and then corrects it without scolding.

The presence of animals is not decor. Horses refuse to be hurried and demonstrate a sagacity that the people cannot imitate. Dogs bark when the air alters, a sound that tells the film where to place the next cut. Bats appear with an innocence that laughs at the history in which they have been made to serve as spies and as heralds. The white rats do their work. They eat. They run. They learn nothing and teach nothing. They return the city to a truth older than trade.

The film’s patience is often mistaken for solemnity. It is not solemn. It is careful. It refuses the rhetoric by which fear is sold and by which pity is turned into an advertisement for the seller. It asks the viewer to remain at the side of the picture and to accept that the centre is occupied by the time of the tale rather than by opinion. Those who expect an argument will be surprised to discover that an argument has occurred and that it has left them with nothing to oppose. Those who expect to be spared the work of looking will be surprised to discover that the work has been done in the muscles of the face, the hand between the thighs and in the hand that rests on the arm of the chair.

Because it belongs to a tradition, the film is often placed in a shelf of categories that reassure the manager of shelves. It does not resist this. It simply fails to be contained by it. The shelf does not matter once the show begins. What matters is the duration shared by the room and the image and the breath that travels between them. In that duration the distinctions that keep us polite grow thin without collapsing. We are allowed to meet death without turning it into a spectacle. We are allowed to see eros without turning it into a confession. We are allowed to watch a city practice its forms of life until those forms become a tender comedy.

If one were to gather the objects that the film treats as confidants, the list would be short and exact. A chair that has learned to hold the posture of a decision. A bed that refuses to advertise itself as a theatre. A door that allows a body to pass and then returns to its single job without complaint. A stair that understands the patience required to carry a person down without making a ceremony of descent. A window that insists upon the neutrality of the outside. A table that is prepared to be a place of both counsel and betrayal and that cannot tell the difference. The camera loves these objects as one loves people who do not require praise.

The story is often told as a lesson about the danger of desire and about the price of ambition. The film declines to teach that lesson. It would be too easy and too flattering. It tells another story, which is that life arranges itself in forms that outlast the meaning we give them and that these forms are not our enemies. A bed can be a place where hunger is invented and where hunger is spent. A street can be a place where fate keeps its appointment and where fate misses the meeting. A sea can be the surface over which death is imported and the mirror in which a child discovers her face. The forms remain. We pass among them. The film gives them their dignity.

In the last image we maybe think we have been offered a path away from the city that has learned to be an island. A rider moves across a plain that will never remember a hoofprint. The light is not an omen. It is a light. The rider is not a promise. He is a man who can no longer choose. The film allows the illusion of departure and then quietly removes its guarantee. We are left in the room with a knowledge that is not an answer. We stand and we do not speak for a moment because speech would be unfaithful to a climate that asked for attention and received it.

Of course to speak of the film is to risk replacing that climate with phrases that pretend to have rescued it. The only honest thing one can do is to repeat the discipline it trained in the eye and the ear. Look until the image asks you to be still. Listen until the sound has taught you that silence is a way of hearing. Accept that pity can live without relief. Accept that fear can be more intelligent than courage. Accept that a face which would ordinarily be made an allegory is also the place where a person had dinner and went to sleep.

Afterwards, streets appear both older and more exact. There are windows that have learned to withhold and doors that have learned to delay. There are tables prepared for dinner and there are a few rats that must be forgiven for what they resemble. The sea is not far. The town expects the ship and the ship will not come. Or it will come and everyone will pretend to be surprised. The film has made this indifference tolerable by granting every object the right to be itself. That right is not something we can give. It is something we can only recognise. The recognition is the work asked of us. The work is the only proof that the images have entered us without wounding and without our turning them into shields.

The tale would be unbearable if it claimed to be new. It bears itself well because it accepts its age and because it uses age as a form of modesty. It does not seek to persuade us that this time the stranger could be redeemed if only the words were chosen with greater care. It does not attempt to persuade us that the town could be saved if only the doctor were less ridiculous or the clerk less greedy or the woman more devout. It allows each to remain within reach of the person he or she has always been in stories like these. It allows the viewer to stand near them without harvesting a lesson. In that nearness we receive what the first faces promised when they looked at us from their stone shelves. We receive the freedom to be equal to a picture that carries death and love as calmly as chairs and doors. We receive the day back from a film that has spent it without waste.