Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Durer’s Melencolia 1

Mitchell B. Merback, Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Durer’s Melencolia 1 ,

Zone Books 2017.

‘Sometimes my burden is more than I can bear

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there

I was born here and I’ll die here, against my will

I know it looks like I’m movin’ but I’m standin’ still

Every nerve in my body is so naked and numb

I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from

Don’t even hear the murmur of a prayer

It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there‘

(Bob Dylan: Not Dark Yet)

‘Rain, foreign lorries and the city is never really dark enough.This world is one of mysterious plagues. Mountains of frozen junk fill our skulls. We read and read. We try . We watch pictures everywhere we go. We dread what’s to come and what has happened already. It’s certain that something will come. It’s a strenuous ordeal. Each time we read, write, watch, then the world is different, augmented. We continually ask not technical but philosophical questions: how do we know of any harmony? What if the intervals in the masterpieces of many centuries are all, secretly, false? Such self-doubt, it overwhelms us. Our unsurpassable enchantment, its harmony and echo, which we’ve carried in our heads, year after year, suffering for, lusting after, willing, is maybe just an illusion of self-grandeur. We fill up with violence, hedonism and despair. Our erotic concentration is merely the pressure of bad times, soil on a mole’s head. In the middle of the night we can’t sleep. We are delirious with unhinged arrogance. But we can’t take possession of our ideals. And we feel incapable of making it right. Mistakes are always made and the concern is always, always there. Doubts. Sickness. Our distinct qualities fracture. We are gigantic snails fearful of huger feet. Our inspiration has drained away into an ugly jug of insanity. Shopping, traffic, social media and advertising, experimental lives, petrified signs … and if we’re asking Levebre’s nauseous question ‘… is one’s only achievement to continue that long line of failures, self-destructions and fatal spells lasting from Jude the Obscure to Antonin Artaud?’ - then this is our melancholy.’

Durer worked inside the pressures of his age, inside collisions of spirit and nature, good and evil and the majesty and vomit of existence that marked his time. Between hot derangement and ice-cold boredom he reconfigured the relationships between Renaissance metaphors. Rebirth and revival, darkness and light and Renaissance misery’s peculiar character – Melancholia – were all altered. In so doing he raised painting to the rhetorical level of Petrarchan poetry. Merback’s stunning book makes the case for the inception of a new genre of imagery in Durer’s Melencolia 1, that of the allegorical-speculative image. It was an image in the service of cognitive-spiritual exercise.

Durer’s engraving of 1514 held the incoherent energies of the Black Death (14th century) and the Wars of Religion (16th -17thcentury) up against the official optimistic propaganda about the time. The Renaissance’s lived reality was more deranged than the rule of reason was advertised as being. It was a time of more frequent and more destructive warfare than ever before. A litany of eruptions and pressures fed it: the failure of the Crusades in the decades after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the Siege of Vienna in 1529, the Peasants Revolt in Southern Germany, the crisis of faith brought on by the Radical theologians and alongside these, ecological breakdowns that brought ancient diseases like leprosy and modern ones like syphilis into a shared European consciousness. The Devil and his minions were rife. A radical disjunction between the reality and the idealism of the Renaissance required an art capable of confronting this.

Durer’s engraving is embedded in this complexity and works to make sense of it. The greater the ideal of perfection, the more imperfection clarified and threatened to destroy it. The despair that this perception threatened was most acute in those striving for its ideal. They were afflicted by bouts of melancholias lethargic hopelessness following frantic work-obsession. This form of Melancholia links to ‘acedia’ – spiritual sloth, and ‘tristia’ – spiritual sadness. It snakes through the Kantian sublime, the ennui and Weltschmerz of Romanticism and the boredom of the existentialists. Where comes the eruption of desire for perfection? Perhaps its an instinct, although Freud doubts this, noting it would be more trouble than its worth for both ego and body.

Durer warned his students over the perils of overexertion . ‘The temptation to go beyond one’s limits leads to falling under the hand of melancholy,’ warns Durer in his unfinished ‘Nourishment for young Painters’ of 1512-13. Yet he continued to work at a frenzy and was constantly afflicted by the despair that followed.The misery wrought by seeking perfection was not just physical exhaustion. It was a sense of overwhelming failure. It was Francesca Petrarca who recast anew the problems of ceaselessly striving towards perfection when `… he complains to Augustinus about the failure of meditations to overcome sorrow, melancholy, the feebleness of his efforts … the plague of phantasms which shatter and wreck your thoughts.’ The ‘natural end’ of Aristotelian eudaimonia is provisional , qualified and doomed. The calling card of virtue-seeking is an experience of ‘inner discord.’ Seeking harmonious truth is riddled with frustrations, setbacks, reversals and wrong turns.

Like Durer, Virgil, Cicero and Seneca lived amidst pervasive error and gloom and ‘… they failed to arrive at the destination they sought…’.Petrarch is considered the first modern man because of his individualism and the line he drew between ancient and modern history. Mazzotta , the unrivalled critic of Dante and Petrarch, writes that: ‘In Petrarch’s poetry time’s ruptured dimensions (past, fleeting present, and expectation of the future) are internalized within the self, and they are even identified as the constitutive, broken pieces of the self.’

Gur Zak writes that in Petrarch we find a figure organising a sustained effort to ‘cope with the experience of fragmentation’, recovering the self as ‘ a state of mind from which we have been exiled.’ The prevailing reality for the Renaissance humanist was that perfection remained perpetually close but always out of reach. In ‘Africa‘ Petrarch writes: ‘ My fate is to live amid varied and confusing storms. But …[this] sleep of forgetfulness will not last forever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance.’ It is the frustrated achievement in the present that is the source of a distinctive misery that ‘Melencolia 1’ addresses.

Petrarch’s rhetorical therapy was reading and writing. ‘On The Remedy of Two Kinds of Fortune‘ built on medieval specululum literature and Stoicism. Petrarchan rhetoric allied with philosophy to care for the soul and moved rhetorical eloquence from the realm of moral philosophy and civic duty to an inward ‘care of the soul’ . In this he was following Seneca, where style and persuasion were transformative. Petrarch’s effort was to revive the epistolary genre of consolatio – consolation in times of grief and loss – and to innovate a philosophical therapy of the word – rooted in Socratic dialogue, Aristotelian rhetoric and the Stoic training for life. Durer’s innovation was to transfer these qualities to painting.Hellenistic and Roman schools trained reason , will and memory to acquire virtus to overcome the pull of fear and sorrow. They aimed at Pierre Hadot’s ‘metamorphosis of the personality’. The Stoic precept of ‘conversion to self’…’ drove this. As Petrarch puts it:’ … you subject your mind to reason, or, to express it differently, you to yourself.’

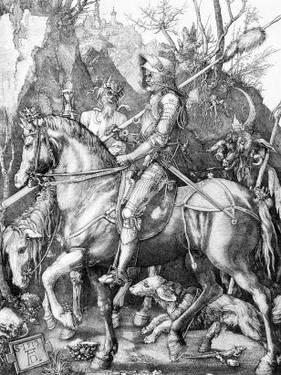

Merback presents Stoicism and Augustinianism as Bouwsma’s ‘two faces of Renaissance humanism.’ It is not surprising then that Durer fuses neo-Stoicim with his faith . Neo-Stoic Erasmus’s ‘ Manuel of a Christian Knight’ describe vigilance in the face of ill-fortune and the constant struggle against the forces of darkness coupled with the determination to love God and wisdom. Panofsky sees this in Durer’s three master engravings: ‘Knight, Death and the Devil’ of 1517; ‘St Jerome in his Study’ and ‘Melancholia 1′.

The ‘St Jerome’ represents a vita contemplative. ‘The Knight’ shows a a vita activa, the figure forging through the wasteland despite the threats and distractions surrounding him. Merback confesses however that, contrary to more or less everyone, no programmatic unity between the three has been established. Peter Parshall finds some in ‘its relation to mimesis, invention, verism, and certainty and the dangers inherent in allowing it to wander beyond its proper bounds.’ The ‘Knight, Death and Devil’ …. ‘exploits the capacity of engraving to evoke hard and soft surfaces and to illustrate (as well as to exemplify) boundaries that cannot be transgressed…’ St Jerome… ‘ captures the elusive, indeed unpicturable qualities of atmosphere, light and temperature, allying these conditions with the ineffable movements of the mind.’

But Melencolia 1 hides its motives from him and his claim remains incomplete. What is the perplexity of Melencolia about? This is Merback’s question. His intriguing and ingenious answer is original and suggestive. Melencolia 1 is disturbing in all sorts of ways. It has two light sources not one. It seems to have a nocturnal messenger bringing the word Melencolia 1 to earth. An assemblage of things evoke the delusions of the ‘black bile of Luther, ‘the devil’s bath.’ But there seems no interpretive code. Merback takes Parshall’s ‘ deep suspicion of the mind’s operations’ as a central theme, but twists it to a new insight.‘ According to the theory put forward in this book, Durer’s print is… to stimulate a certain kind of receptive process in the beholder. That process [is] therapeutic in nature – therapeutic in the Petrarchan sense, as a union of rhetoric and philosophy in the pursuit of virtue, and also in the ‘medical’ sense, as a stimulant and balm for rebalancing the mind.’ It’s a ‘cognitive exercise aimed at restoring and fostering health.’ The book works to establish the plausibility of this thesis.

In chapter one Merback shows how Durer extended the rhetorical resources of printed pictures for speculative thinking. Heinrich Wolfflin (1864-1945) noted ‘Melencolia 1’s ‘chaos of objects’ and the close affinity it had with the genre of Vexierbild, the puzzle picture. Joachim Camerarius (1500-74) had already noted the puzzling quality of the image of Melencolia herself:‘ Next to her we can see instruments belonging to the arts, books, rulers, compasses, squares and, besides, tools of metal and several of wood. In order to show that such afflicted minds commonly grasp everything and how they are frequently carried away into absurdities, he reared up in front of her a ladder into the clouds, while the ascent by means of rungs is as it were impeded by a square block of stone.’

All this suggests the picture is indeed a rebus. Its hidden discourse maybe moralistic, aesthetic, protoscientific, epistemological, maybe allegorical as in ‘allos’ , meaning ‘other’ and the verb ‘agoreuo’ – “to speak”. In their influential volume on Durer’s work Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl saw things in this way, where ‘ … the visible representation completely answers to the invisible notion.’ It’s a great book but Merback thinks it doesn’t quite succeed. However, it did enrich understanding of Renaissance melancholia. Panofsky expanded the notion of melancholy via Marsilio Ficino’s (1433-99) studies of its inspired version. Connected with bile and earth, Ficino wrote about how heated bile led to the creative furies. Ficino linked this particular species of melancholy to occult external powers routed through ritual, astral magic, kabala, divination, numerology, astrology and angelology. This melancholy is a gift of Saturn, most feared of the planets.

Panofsky writes: ‘ Like Melancholia, so too does Saturn, this demon of contradictions, on the one hand endow the soul with sloth and dullness, on the other, with the power of intelligence and contemplation; like melancholy, Saturn also constantly threatens those subjected to him… with the dangers of depression or manic ecstasy.’ Panofsky sees the Durer image in these terms, the figure threatened by Saturnalian derangements. Against this Konrad Hoffmann in 1978 saw the seated figure as having already overcome the threat of melancholia by being protected from depressible astral influences by the numerological square above her head. Whatever, undoubtedly Saturnalian astrological occultism was another strand of the entwined cognitive technologies available to Durer, joining medical science, neo-stoicism and Christianity. Frances Yeats also saw occult influences. She linked Durer with kabala and the word magic of Johannes Reuchlin (1455-1522). She saw not depressed inactivity but ‘intense visionary trance, a state guaranteed against demonic intervention by angelic guidance.’ In proposing anti-Apollonian themes of theurgy, magic, kabala, witchcraft and occult, Dionysian forces she makes clear that the revolutionary eruption of external forces into explanations of fortune and misfortune were important to Durer.

Panofsky’s work was ever pro Apollonian, despite this, and confronted Aby Warburg’s Dionysianism as they worked at the Warburg Institute, declaring ‘Athens must be wrested back, over and over again, from Alexandria’. Walter Benjamin thought that the Durer picture ‘anticipates the baroque in many respects… images and figures presented in the German Trauerspiel are dedicated to Durer’s genius of winged melancholy.’ Apart from the dialectical Benjamin, however, everyone wanting to find a unified interpretation has failed. In the light of this Merback returns us to the idea of Denkbild – a ‘thought image’. This is roughly like a Platonic Form and also an ‘image of thought’ where the form of thought becomes its content. Merback asks us to consider that perhaps there is no code to break. He takes seriously Joseph Leo Loerner when he writes: ‘Instead of mediating a meaning, Melencolia 1 seems designed to generate multiple and contradictory readings, to clue its viewers to an endless exegetical labour until, exhausted in the end, they discover their own portrait in Durer’s sleepless, inactive personification of melancholy. Interpreting the engraving itself becomes a detour to self-reflection, just as all the arts and sciences whose tools clutter the print’s foreground finally return their practitioners to the state of mind absorbed in itself.’

Understood in these terms Durer is both allegorical and speculative, refraining to seek hidden things yet still mobilizing cognition-producing results. Merback summarises this:

‘Understood in psychosomatic and somatopsychic terms as a kind of hydraulics of the soul’s higher and lower faculties, the dynamic cognition sparked, sustained and excercised by Dürer’s print was… the common concern of Renaissance painters, poets, rhetoricians, and physicians: a “movement” of the soul from one state to another, a return of the self to itself, a therapy of the passions aimed at the restoration of balance and health.’

Merback shows how the print’s perplexing visual structure serves as a training ground for speculation, offering free reign speculation in order to rebalance the mind and counter its susceptibility to flux. Michel Jeanneret in his ‘Perpetual Motion: Transforming Shapes in the Renaissance from Da Vinci to Montaigne‘ writes of the artistic and therapeutic use of indeterminacy: ‘‘Indetermination is the choice springboard for artistic reverie and imagination because it is the necessary passage for determination, the vacant site where new forms take shape. At this stage things do not yet exist, their shape is not fixed, their genesis is still a pure project…. This vagueness, which paralyses the geometric spirit, stimulates the creative imagination.’ I think the indeterminate landscaping works of Caspar David Friedrich might be seen like this, and the plays of Beckett too.

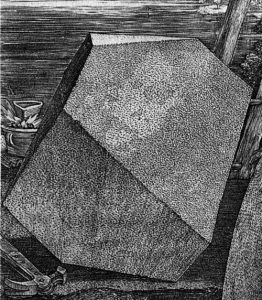

In his ‘St Jerome’ geometrical forces of perspective bind everything. Wojciech Balus writes of it: ‘The whole composition gives the impression of being influenced by a magnetic field passing through the saint’s cell and arranging the objects along the lines of force.’ In Melencolia 1, by contrast, any geometrical forces are perplexing and weak. Geometric forces are ‘silent subversives, arousing our expectation of optical uniformity without ever satisfying it.’ The ladder insists an ‘impure harmony.’ The instability of the large polyhedron leaves the scene in turbulence. Merback notes that; ‘Visual ductus as a governing element of style breaks down here, as if corrupted or short-circuited…The eye’s free passage into the distance is blocked, causing it to circle back into the chaos of objects, where it finds no obvious place of repose…Optical movement through the accumulated objects and bodies takes on the quality of an agitated restlessness, giving way to a sense of claustrophobic unease…geometry gone melancholy.’

Representing a polyhedron was one of the big challenges of the Renaissance at the time. Durer experimented with perspective machines. Yet he recognized that a strict rule-bound geometry didn’t solve all aesthetic problems. He shaved away dimensions in a process of ‘legitimate construction.’ The result has affinities with the ‘magic square’ of Jupiter on the wall behind Melencolia. It is a visual version of negation that denies that it’s a negative attribute to be taken in a certain way. It is a negation that doesn’t provide a definition of anything. Rather, it is a negation that suggests a non-correspondence between subject and predicate and its logical contrary. It’s a geometry that has gone awry like literally attributing ‘sweetness’ to a geometric line. ‘Line’ and ‘sweet’ have equal extension and so can’t be combined into intellectual syntheis (compare with ‘straight’ and ‘line’ which don’t – line being more comprehensive, or ‘crooked’ and ‘line’ where we can represent a non-straight line but not a crooked line without a line of any sort) . The refusal of such a synthesis is continuous in the picture.

Optical unease has a reverberative effect on form so that the polyhedron seems weirdly possessed of an inner torque rotating away from inner axis. There’s an uncanny anamorphic quality to it that disorientates the viewer and draws attention to the angle of entry into the illusion by the viewer. The magic square above Melecoli’s head also has affinities with the distruptions of Jupiter. As with the strange geometries the square seems to be a demand not to solve the puzzle. Everything sends the eye back so that, for Merback, ‘… the form disturbs visual activity inside the virtual space of the image and at the same time directs it across its surface, where forms interact.’

Everything invites speculation rather than resolution. This is Merback’s insight and what makes his approach new. Everyone sees the puzzling nature of Durer’s print. They see it as an invitation to find the code and solve the puzzle. Merback sees it instead as an invitation for gentle cognitive play enabled and threatened by ‘the mind captivated in a web of visual obstruction.’ The therapeutic process is embedded in the design. The experience of the viewer is recognized in the picture. It’s in this recognition that the affliction of melancholia is overcome. A prototype of this approach is found in Reindert Falkenburg writing about Petrarch Master’s web engraving. The idea here is that the engraving serves to instruct ethical insight ‘… by letting him take the medicine of insight against the illness of quick and superficial judgment regarding good and bad fortune, to which mankind is inclined to succumb.’ It mobilizes antibodies against ungovernable attachments and desires. Merback likens this to John Dewey’s idea of; “What is done and what is undergone are… reciprocally, cumulatively, and continuously instrumental to each other.’ So the visual-rhetorical rather than the symbolic is important to Merback’s interpretation of Melencolia 1.

The symbolic hints – such as Camerarius seeing the ladder as; ‘… the unrestrained and often disastrously absurd flights of which melancholic minds are capable,’ joins with Heckscher’s insight: ‘The path of… purification knows, generally speaking, two fundamental possibilities: horizontal and vertical, pilgrimage and ascent.’ What Melencolia 1 stimulates is, for Merback, akin to ‘ what Latin theologians of the Middle Ages called speculatio, a natural-philosophical mode of seeing that would, in the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, become intergral to humanist ethical education, Christian naturalism, and secular science.’ We are confronting the double roots of theological thinking (Romans 1:20 and Augustine) and German mysticism (the Dominican Heinrich Suso) in this approach. We have a focus on sensory and supra sensory sight where speculation is an intermediary, allowing us to be open to discovery, wonder and knowledge. Boethius writes of this in his ‘The Consolations of Philosophy‘ : ‘ … the lofty watchtower of his providence… embracing the infinite spaces of past and future.’ Speculation is understood as an Archimedean point of human knowing where ‘… Obscurity announces a particular sort of meditation game,’ as Mary Carruthers puts it. She continues, ‘Like all games it is to be enjoyed for its own sake and also – since conferring a benefit helps to license one’s enjoyment – for the salubrious exercising and strengthening of one’s wits.’Speculation brings refreshment. ‘Like the medieval work marked by an often perplexing diversity and varietas, or the paradigmatic “unfinished” Renaissance work, perpetually in motion, the speculative image is as inherently open-ended as the human mind is constantly active.’

The Benedictine Peter of Celle (1183) writes: ‘if the soul is thus compassed about with such a harmonious variety, it will avoid boredom and receive its cure.’ Mystery and illusion, ignorance and puzzles become the ground for speculation and with that comes the power of spiritual, psychological and physical healing. Yet it is tempered by the human immanence and limits of being creatures on earth: ‘If speculation carries thought toward recognition of an order within the fertile chaos of things, that vision of order will always be provisional, its power to illuminate always probationary.’Merback is quick to distance this enjoinment to speculate from postmodernism. Durer’s magical, medical, moral and penitential therapeutics believe the syndrome of melencolia is actually treatable. Health and illness are real. Indeterminacy is about condemning us to endless wandering bereft of meaning. The vagueness of semi-existence was to spur the creative imagination on. Humanism brought ‘ a fundamentally altered way of living… the ideal of the speculative life, in which the ‘sovereignty of the human mind’ seemed to be most nearly realized; for only the ‘via contemplativa’ is based on the self-reliance and self-sufficiency of a process of thought which is its own justification.’

Melencolia 1 is an example a new genre of Christian art directed towards therapeutic ends, where some expectations are metaphorical, others concrete and practical. For Durer therapy’ in both Greek and Latin, encompasses treatment, care, healing and attention. European visual culture long before industrialization knew of therapies of the image. Art history itself is aware of them and their various forms. There were devotional images for emotional training and visual-sacramental therapy. There were votive images as relays for securing the health of a body and the health of a soul through heavenly intercession. There were cult images for both votive function and a quasi-magic of protection and cure. There were meditative images for spiritual exercises.

Merback’s innovative work presses now for the identification of a new image, the image of the allegorical-speculative image for cognitive-spiritual exercise. These images were not stepping stones to metaphysical truths. They aimed at a Petrarchan practical and ethical therapy in the world. In this they link with the complex pedigree of catharsis, Aristotle’s best-known therapy. Merback argues therefore that Durer’s Melencolia 1 is ‘ an erudite portrayal of the peculiar misery that grips creative people, melancholia, but also an instrument for remedying it.’ Importantly, Merback’s approach answers those who have objected to the medical metaphor of catharsis in Aristotle on the grounds that it denies that emotions are cognitive. The emotion of Melencolia here is understood as being cognitive, as is the proposed therapy. By dovetailing this with medical arts Merback is pushing back against this objection, found for example, in Richard Sorabji’s classic ‘Emotion and Peace of Mind‘ which discusses this point at length in general but surprisingly doesn’t discuss Melancholia as far as I can see.

Merback examines the background medical, philosophical, occult and theological accounts of the relation of the body, mind and soul of the time. His account solidifies his account of the therapeutic image. A dominant strand of thinking takes Galen’s thesis that capacities of the soul follow the blends in the body. This notion of the soul as psychosomatic was linked in Durer’s time with Ulrich Pindrrer from Nordlingen . A Christian doctor, he too thought body and soul were linked. Only by bridging them could the higher knowledge of God be reached. Naturalism was therefore seen as a way to eternal truths of God and soul. Contemporary medicine saw melancholia as requiring a combination of therapies: ‘pharmacological, psychological, philosophical and magical.’ Contemporary thinkers should heed this: behind the polished idealized separations of ideologues is a blended, nuanced complexity that belies the nursery stories of the Renaissance’s smiling cheer-leaders.Artistic innovations were taking place too.

Durer’s life-time saw landscape emerging as an independent genre of art and as a therapeutic resource. It’s use of perspective and the optical conquest of space presented panoramas to heal the speculating mind. Landscape invited viewers to release themselves into the opened vistas made possible by landscape’s proto-scientific description of natural phenomena, it’s use of vanishing points and perfect geometries to create visualized spaces for rumination and therapy. Landscape’s emergence coincided with the specialisation of art in cities such as Antwerp. It became part of practical regimes of health and hygiene. Frances Gage wrote about the Sienese physician Giulio Mancini (1559-1630) who admired Durer and who understood landscape paintings as ways to coordinate body, eyes and mind. Mancini’s therapeutic conception of landscape painting sees it as ‘… a major force in the development of princely art collecting in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.’ Robert Burton himself (1577-1640) ‘eased his grief’… [in]… those well furnished Cloisters and Galleries of the Roman cardinals, so richly stored with all moderne Pictures, old statues and Antiques.’

Landscape painting and gardening design was a virtual space for meditative renewal . Leon Battista Alberti captures this in his ‘Ten Books on Architecture‘ where he writes that:‘ Those who suffer from fever are offered much relief by the sight of painted fountains, rivers and running brooks, a fact which anyone can put to the test; for if by chance he lies in bed one night unable to sleep, he need only turn his imagination to limpid waters and fountains which he had seen at one time or another, or perhaps some lake, and his dry feeling will disappear all at once and sleep come upon him as the sweetest of slumbers.’ Landscape imagery multi-tasks – it represents nature and the cosmos. It does allegory. It functions meditatively, philosophically, hygienically and all in the service of human flourishing. Attention to the world merged with attention to the self and activated a shift in perspective. For Durer it helped him to understand viewing art as practical activity that removes blockages and opens new pathways to health.

It also links to a mobilization of mimetic images to secure benefits, in a kind of better kind of magic. Its resources combine powers assumed in magic – sympathetic (like cures like), antipathetic (cure by law of contraries) and amuletic (protective). The modern new genre of landscape functioned as Christian iconography already did: an art to cure the soul. ‘To heal and be healed was to enter into an economy of redemption in which the exchange of gifts and services, suffrages and sacrifice, cross the boundary between material and spiritual planes,’ writes Marcia Kupfer. Durer’s Landauer Alterpiece of 1508-11 show his understanding as a physician of the soul.

Here we have images in the setting of private devotion which are less image types than a constellation of image functions. This was a key domain of sacramental, spiritual and ethical therapy in Durer’s time. Seeing an image was to unleash something of the images’ immanent sanctity onto the viewer and awaken spiritual well being. In this art the contemplative immersion in an image was interwoven with self-examination. Images to console were a third dimension. An images’ theatrical elements were designed to close the distance between devotee and loving presence. So the many visionary unions with lactating Virgins or Suffering Christs attributed to mystic St Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) were to create tactile, physical experiences of spiritual wellness. Bodies are drawn together in tender embraces, showing the intimate blending of soul, mind and body in sacred and immanent union. This linked the efficacies of images stemming from sacramental, consecrated or enchanted objects with efficacies effecting human agency via rituals of performance and communication. And it helps us understand Rhetoric as a third efficacy. It becomes a bridge between receptiveness of the sensitive soul and reason in the intellectual soul. Rhetoric was ancient philosophy’s model for bridging.

Speculative labour is reflective and invites mirror imagery. The ‘Spiegel del Vernunft’ of 1488 is the ‘Mirror of Understanding’ and addresses carnal man for the sake of his eternal soul. Its mirror motifs are not metaphors for self-reflection but phenomenological prompts and affordances within a meditative environment it creates. It is a process that transforms self reflection to self reform via self recognition. The human soul is seen as a living mirror of God’s perfection, the imago dei of Aquinas. For this reason therapeutic expectations were etched deeply in collective perceptions about the interplay between supernatural and natural forces, learned and folk attitudes about body and mind, and sacramental values of substances both in and out of clerical control. This is deeply embedded in the long-standing many-sided alliance between art and medicine. We see this in the illustration of medical treatises, anatomy art, the fluid commerce between art and pharmacology, and art’s own ‘common specialist culture’ based on practical scientific knowledge of natural substances.’

The Christian artist as the medicus of the soul and mind, was, according to Merback, ‘… an artisanal counterpart to the rhetorical healer charged with the consolation of the souls through reason and wisdom.’ Merback insists that ‘… [t]here is, embedded in Durer’s masterwork, a dianoetic logic that transforms the beholder’s real or vicarious experience of melancholic disturbance into a kind of tragic knowledge that his own destiny, and his own prospects for well-being, are at stake.’ He cites Kierkegaard’s ‘At a Graveside’ to capture the stakes of this work. ‘One who is living does not have it in his power to stop time, to find rest outside time in the perfect conclusion, in a conclusion of joy as if there were no tomorrow, in a conclusion of sorrow as if it could not be a drop more bitter, in a conclusion of the contemplation as if meaning were entirely finished and the contemplation were not a part of the meaning.’

In Melencolia 1 the strange figure embodies Panofsky’s ‘… general idea of gloomy inertia’ , one ‘paralysed not by sloth but by thought’. The affliction is the condition of what Panofsky calls being ‘super awake’. Who hasn’t been in this state, excited by some idea or book and disturbed to a point of deranged awakeness? For Panofsky ‘…The creature is a ‘superior being ‘ superior not only by virtue of her wings but also by virtue of her intelligence and imagination.’ She is a ‘thinking being in perplexity.’ For this reason the print demands the super attentiveness of the super awake. As such it overlaps with the active stillness of late devotional figures of Christ. The observer enters into an active self identification with the ‘fiction’ of the image. It becomes a matter and process of transference, a ‘thinking in perplexity’ to bring about a renewal of creative thought and action. Melencolia 1 demands we see it as a temporal sequence. Past activity is strewn about as well as the present. Melancholia passes. It flits in and out. The image deems to ‘reconstruct the prior act… of gauging the radius’. It arouses in the onlooker the awareness that time is like this and that your life too is moving forward towards its final end.

Thus ‘the narrative quality of experience’ is embedded in the image. The spectator becomes an agent of the passage towards clarification. She collaborates in a return to creativity. Yet there is tragedy in the shared fate of beholder and artist alike. ‘Born under Saturn’ – creative geniuses and overworked art students both – this offers not a cure but an alleviation of symptoms so we can go on. It’s that terrible Beckettian two-step: I can’t go on. I go on. Any hallucinatory intensity is tempered and damped down in the Durer. This lends credence to Merbeck’s claim that it represents a new therapeutic art genre. Compared to Bosch or Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) who did 4 painted Melancholias with details borrowed from Durer himself, we see rampaging demonic beings in orgiastic abandon deranged by melancholic distemper flying about. These and other images made links between melancholy and the ‘delusions of witchcraft.’ The wild riders were Saturn’s children. ‘Here we are half-way between the Renaissance era’s persistent fear of demons… and the Aristotleian-Galenic observation of natural causes, an “enlightened” view of witchcraft … in Goya’s ‘The Spell’ of 1798.’

But no such demonic forces haunt Durer’s version. A bat merely hints at them. Rather, Durer’s figure is held in between hot frenzy and cold indifference. Melancholia was seen as a distinct illness, and had been from way back. Hippocratus (4-5th BCE) wrote about it in terms of ‘… aversion to food, despondency, sleeplessness, irritability, and restlessness’. Linked to the four humours – blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile, it was a condition of ‘fear and despondency persisting for a long time. Aristotelians saw it as combining solitude, despair, sadness and greed. The imaginative species was linked to the Saturnine mind of an ‘inspired melancholy’. In this we find Galen’s Aristotelian naturalism and medical notions influenced by Plato’s idea of the divine madness of imagination. Constantinus the African (1090) wrote about it as being something more connected with the notion of taking activities too far, of becoming obsessed and working too hard in seeking perfection.

He says : “ Some … like solitude and the dark and living apart from mankind. Others love spaciousness, light, and meadowy surroundings, and gardens rich in fruits and streams. Some love riding, listening to different sorts of music, or conversing with wise or amiable people… Some sleep too much, some weep, some laugh…’‘Overdoing it’ is the cause according to him : ‘ … strenuous thinking, remembering, investigating, imagining, seeking the naming of things, and fantasies and judgements, whether apt or mere suspicions… overexert themselves with reading philosophical books, or books on medicine and logic, or books which permit a view on all things; as well as books on the origin of numbers, on the sciences which the Greeks called arithmetic; on the origins of the heavenly spheres and the stars… geometery; and the science of composition, namely songs and notes, which means the same as the greek word ‘music’….The reason why their soul falls sick lies in fatigue and overexertion, as Hippocrates says.’Weird medical notions of thermal balance, toxic vapors, black and yellow burnt bile, and abnormal sensory images noted by Galen, where ‘ one patient believes that he has been turned into a kind of snail and therefore runs away from everyone he meets lest his shell should get crushed…,’ combined with Philip Melanchthon’s ideas in his ‘Commentarius de Anima’ (1540) about Luther’s notion of the whole man.

Galenic anatomy joined with natural philosophy, and medical knowledge of the body joined with Christian knowledge of the soul. Where Cranach’s images narrow the range for free association in its attempt to demystify melancholia, Durer’s widens it. It broadened to mix with other treatments – blood lettings, fasting, fomentations, anointings, enemas, poultices, massages, baths, walking, plasters, oils, ointments, modest entertainments. Even philosophical discussion was considered a treatment; ‘… for by their words philosophers help to banish fear, sorrow, and wrath, and in so doing make no small contribution to the health of the body.’ Sex also had a therapeutic role because it calmed the passions and ‘dissipated fixed ideas from the soul’ according to Oribasius of Pergamon (325-403) Paul Of Aegina (625-90)agreed, saying that: ‘[t]he best possible remedy for melancholia is coitus’ whilst Constantinus the African noted that ‘ Sexual intercourse pacifies, turns pridefulness into austerity, and aids those who suffer melancholy’. Durer’s print brings art into this heady mix as a passive exercise. His speculative image offering a moderate workout that calms rather than excites passions. It stimulates the higher powers of the soul, dispelling the vapors in an act of katharsis to clarify the passions with both ethical and spiritual consequences.

As noted earlier, he was working in a revolutionary time which introduced Astral forces – powers from the outside – into the mix. Influences of the planets were alternatives to internal influences derived from understanding the body as a microcosm in need of humeral, thermal and hydraulic engineering. The interloping ideas of astrology, divination and magic brought with them new metaphysical approaches to therapeutics. For the likes of Ficino and Cornelius Agrippa von Nettisheim astrology marked a revolution of fundamental significance. But it didn’t displace the older Scholastic engineering but rather complemented and blended with it.

These new forces weren’t always welcomed however. Durer’s friend, the German humanist Konrad Celtis ‘identified himself completely with the customary views of school [that is scholastic ] medicine, and Saturn was for him nothing but a mischief maker who produced sad, labouring, and monkish men’ according to Panofsky. Who no doubt agreed. Durer proclaimed the capacity of his art to mediate philosophical wisdom as early as 1502. Ficino writes about this capacity: “ … through images…. Put together harmonically, through medicines tempered with a certain proper consonance, through vapors and odors completed with similar consonance, through musical songs and sounds… through well-accorded concepts and motions of the imagination, through fitting discourses of reason, through tranquil contemplations of the mind. For just as we expose the body seasonably to the light and heat of the Sun through its daily harmony, that is, through its location, posture, and shape, so also we expose our spirit in order to obtain the occult forces of the stars through a similar harmony of its own, obtained by images… certainly by medicines, and by odors harmonically composed.

Finally we expose our soul and our body to such occult forces through the spirit so prepared for things above (as I have said) – yes, our soul, insofar as it is inclined by its affection to the spirit and the body.’There are astrological images in Durer’s masterpiece – the Jupiter Square, the chart and the bell, the magic square … and for Warburg this is Durer showing : ‘ … the spirit of Saturn neutralized by the individual mental efforts of the thinking creature against whom its rays are directed. Menaced by the ‘most ignoble complex’, the Child of Saturn seeks to elude the baneful planetary influence through contemplative activity. Melancholy holds in her hand, not a base shovel … but the compass of genius. Magically invoked, Jupiter comes to her aid through his benign and moderating influence on Saturn. In a sense, the salvation of the human through the countervailing influence of Jupiter has already taken place; the duel between the planets, as visualized by Lichtenberger, is over; and the magic square hangs on a wall like a votive offering of thanks to the benign and victorious planetary spirit.’

If Merback is right the ‘thinking creature’ invoked is not just the creature in the print but the onlooker. The work’s call to virtue is heeded as a process. In Durer the Christian humanist artist steps into this Petrarchan role. Just as the poet uses eloquence and style to awaken the rational soul to virtue, the artist uses the expressive means at her disposal too. Poetry, painting and rhetoric were each to be counted as an equal ‘art’ ( techne) with its own distinctive capacity to please , persuade and move. This was the moment when the rhetorical forces of painting and drawing were striving to find an equal footing with the poets and Durer must be considered on the front-line of this.

Merbeck makes it clear that Durer addressed himself in Melencolia 1. He always overworked and there were many events both public and private that depressed him. He addressed all his fellow melancholics too. He worked on the image at a time of personal grief – mourning his mother and several close friends in succession – and experienced mournfulness as a ‘pathological state’. Walter Benjamin insightfully writes that mourning takes the ‘… distance between self and the surrounding world’ and transfigures the mundane ‘… into a symbol of some enigmatic wisdom because it lacks any natural, creative relationship to us.’ Mourning fixes itself as ‘an object of contemplation’ resistant to any closed fixed meaning. In such a state mourning becomes a lament over any doomed attempt to make sense of the world. Durer seems to have recognised this as he attempts, as we noted above, to put painting on an equal footing with poetry. He drew on an association of art and healing via St Luke whose legendary act of painting Mary from life drew together the image of the evangelist as painter, writer and, previously, doctor. Painterly knowledge of colouring agents derived from plants, animals and minerals also made the link between art and the apothecary’s art.Alongside Alberti’s claim of ‘Della pittura’ (1435-36) that painting is ‘to move the soul of the beholder,’ Durer also drew on resources from Cicero and Quintilian on rhetoric. Rhetorical theories informed humanist theories of poetry and painting both. Rhetoric linked speech, visible gesture, affect and instruction and extended out of Plato’s theory of communication.

Pedro Lain-Entralgo writes of this in his ‘The Therapy of the World in Classical Antiquity‘ finding the therapeutic category present in the ‘Nichomachean Ethics’, ‘The Politics’, and ‘The Poetics.’ He explains how the revival of literary consolation by the likes of Petrarch, Salutati, Conversini, Manetti and Ficino fed into and resourced therapeutic approaches. He writes: ‘Rejecting dialectic and theoretical learning, humanist writers instead cultivated a practical eloquence that spoke to human emotion, the human will, the human psyche. Evincing a belief in the legitimacy of worldly grief, they provided a solace responsive to the vicissitudes of secular life, and they sometimes offered particular lay perspectives and solutions different from the sterner warnings and cures traditionally advanced by the confessor and pastor. Fully acknowledging the humanity of sorrow, they sought out comforts from neglected troves of Platonic, Stoic, Peripatetic, Epicurean and Christian thought.’

Petrarch took his cue from Cicero who saw philosophy as the healing of the soul. Petrarch complained about the empty words of the doctor at the deathbed ‘ they knit the Hippocratic knots with the Ciceronian warp,’ and worked to develop authentic ways to consolation. In Christian art consolation and memory were drawn together through therapeutic art portraits of the deceased. Here Christian ‘consolatio’ and its German equivalent ‘Trost’ converged in the genre of consoling images. With Durer the artist thematises and realises a form of the soul service akin to rhetorical healing, finding an exact rhetorical corollary in his art to the effects of poetry. This movement also links with the idea of Caritas – charity – an imperfect earthly reflection of God’s perfect infinite love. Paul in Corinthians 1 when talking of theological virtue (faith, hope, charity) for the church, declares charity to be the greatest (13:13). Augustus of Hippo wrote about the dynamic intersection between vertical love – that between God and people and horizontal love connecting neighbours, family, friends. And out of this had grown the Renaissance cult of friendship via Aristotle.

Lorraine Pangle writes that: ‘Friendship is important for Aristotle for much the same reason that virtue and philosophy are. Each in a different way is a perfection of man’s potential as a rational being.’ Erasmus and Thomas More were epistolary friends and Stoics were considered to make the best friends because they neither flatter nor disrupt passions. And coming full circle, Cicero saw friendship as a therapy art for healing the soul.

This secular, Stoical virtue was Christianised via Jerome, Augustine and Isidore of Seville. Alongside friendship, philosophy too brought consolation in a time of sorrow and difficulty. Durer’s dearest friend Pirkheimer wrote that:‘ … the Stoics assert that it is a gift of God that we live, but of philosophy that we live well. Nor is it astonishing since nothing greater or more excellent has been given by God to men… [I speak] of that philosophy which (as Cicero says) heals the mind, removes useless cares, frees from desires, drives out all fears. Instructed and armed with this philosophy, most worthy sister, we bravely bear all misfortunes, sorrows, calamities and labours.’

Durer’s work then is not an abrupt break or sudden innovation. Rather can be seen as growing out of a rich hinterland of religious and humanist thinking and an ethos of care and the collaborative cultivation of virtue. He works in the spirit of Petrarch writing to Albanzani in 1368: ‘… so I succour and comfort you, dear friend, in what time there is, and to the best of my ability, and I comfort myself since we share everything: hopes, fears, joys, and grief. And so, as I have said, I combine our wounds in order to prepare the salves.’ According to Ernest Cassirer Durer never achieved that ‘balance between the requirements of ancient humanism and medieval religiosity…’ but he shared Petrarch’s ambition for a therapy of the passions. Durer worked across media, genres, and across the functional contexts his art served to achieve this. Melencolia 1 is for Merback a therapy for the world-weariness and spiritual sorrow attending the mind and the soul’s lethal quest for perfection. The book’s an astonishment, and woke me up.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Marshall is still biding his time.

First published at 3ammagazine