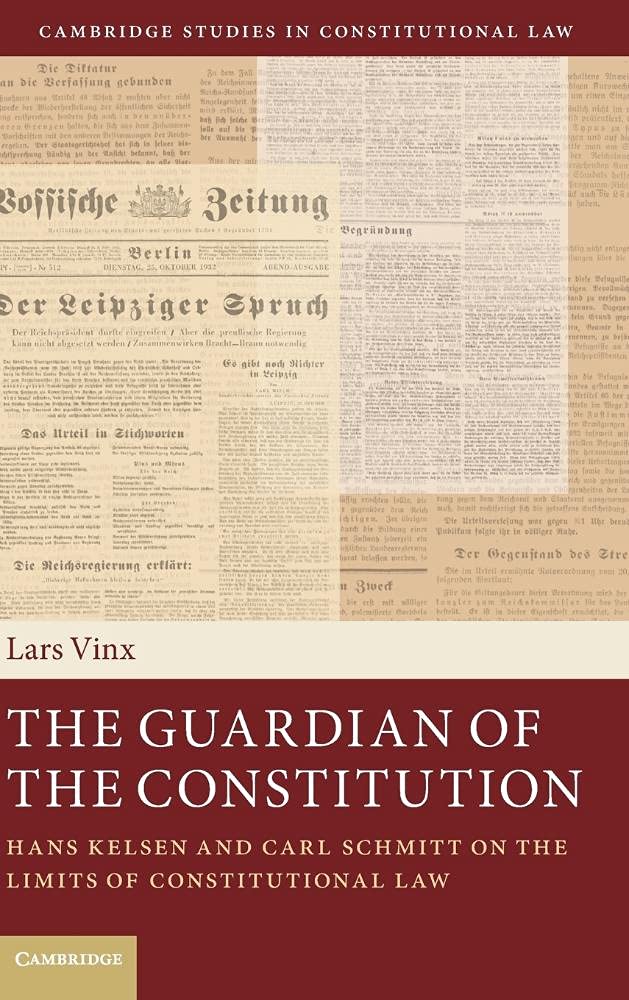

Lars Vinx, The Guardian of the Constitution: Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the Limits of Constitutional Law

Lars Vinx, The Guardian of the Constitution: Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the Limits of Constitutional Law (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Imagine a federal country in which the head of state has decided that the government of one or more of its subsidiary provinces should be suspended or entirely removed for incompetence or malfeasance. Suppose, as well, that national troops have been sent to those areas based on the claim that there is a danger to the public there that cannot be controlled by local law enforcement personnel.

This scenario may remind some readers of what recently occurred between the Trump Administration and the U.S. state of California when U.S. Marines were sent there. The Governor of California, Gavin Newsom, sued the U.S. government, alleging that the actions taken exceeded any legitimate authority provided by the U.S. Constitution. In defense of this claim, California can remind the court of a specific provision contained in the U.S. founding document, viz., the Tenth Amendment, which provides that any powers that were not specifically given to the federal government by the U.S. Constitution, nor prohibited for the states, are reserved to the states themselves, or to the people.

It is true that there is no specific provision in the U.S. Constitution for the President to take over a state government in the case of an emergency there (real or imagined). But there is Federal legislation that entitles the President to “emergency powers” given certain conditions, and the U.S. Supreme Court, the organ of government expected to make the final determination regarding whether the criteria specified in those laws have been met, will surely also consider whether the relevant statutes were unconstitutional in the first place.

One can suppose, of course, a counterfactual situation, one in which our Constitution DOES contain provisions like these:

If a state fails to fulfill its constitutional or legal obligations, the President can use armed forces to enforce them. Specifically, the President can take necessary measures, including using armed forces, to restore public order and security if they are seriously disturbed or endangered. Such actions by the President shall allow for the temporary suspension of fundamental rights like personal liberty, inviolability of dwelling, secrecy of communications, freedom of expression, assembly, association, and property.

However, the President must promptly inform both branches of Congress of any such emergency actions, which shall be terminated immediately pursuant to a majority vote of both the House and the Senate.

Again, while there are no such provisions in our Constitution, it is interesting to consider what the result of the case before SCOTUS would be if there were…and if their decision would be easier or harder to make. Certainly, there would now be no question about the President’s authority, given certain emergency conditions. But there would still be the matter of whether those conditions had actually been met. In addition, there might be questions about the “promptness” of the report to Congress and any activities consequent to any Congressional action on the matter.

One argument bound to come up not only before the Justices but among the populace at large would be whether the President or the Supreme Court is in a better position to determine (i) whether there has actually been an “emergency” in California, and (ii) whether public order has really been “seriously disturbed or endangered.”

It is also interesting to reflect on which would be the more democratic way to resolve this issue–a determination by an elected official with personnel on the ground in Los Angeles, or a group of nine unelected legal scholars who will be required to base their opinion on (perhaps scant) precedents and, maybe, some historical musings about the likely thoughts of John Dickinson on the subject?

While this hypothetical regarding a rather different constitution may be considered somewhat academic in today’s U.S.--it is hardly an exercise in mere scholasticism given today’s political realities. And it is precisely what had to be determined in Germany’s Weimar Republic when the Reich tried to take over administration of Prussia, because their Constitution’s Article 48 contained almost exactly the crucial content summarized above that is absent from the U.S. document. And, as is well known, both the decision rendered by the Leipzig court and the legal jousting over it were central to the eventual Nazi takeover of the country.

Lars Vinx’s The Guardian of the Constitution: Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the Limits of Constitutional Law is thus an extremely timely book. The fine introduction contains all the historical details of this crisis of Weimar federalism and how it contributed to the Nazi takeover in 1933 Germany, a condition that took a World War to remedy.# The main body of the book contains Vinx’s translations of several of the principal antagonistic works of Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the matter of constitutional guardianship. Schmitt, who later became known as Hitler’s favorite jurist, had led the case for the Reich against Prussia, while Kelsen was an Austrian jurist who had helped author his native country’s Constitution of 1920 and had sat on its own constitutional court.

There are six translated works here, three by each of the Weimar disputants. Two by Schmitt are excerpts that make up much of his The Guardian of the Constitution, and the third is his “Closing Statement Before the Staatsgerichtshof” [Constitutional Court]. The Kelsen works are “The Nature and Development of Constitutional Administration”; “Who Ought to be the Guardian of the Constitution?” (a quite savage review of Schmitt’s above-mentioned book); and Kelsen’s final comments on the eventual judgment of the Staatsgerichtshof. Although both men had written on the issue of constitutional guardianship before this time, the translated works here were all written and originally published between 1929 and 1932, during the constitutional crisis between Prussia and the Weimar Republic. While I cannot comment on the accuracy of the translations, they read smoothly, and Vinx’s notes are helpful.

The attempt to remove the government of Prussia is one sort of action that a constitutional guardian might be asked about, and the question may arise whether a court is the appropriate venue for such a determination. But is interpretational authority the sum and substance of constitutional guardianship? Not exactly. The point of a “guardian” here is that, if a constitution is supposed to be the main bedrock or “basic norm” that constitutes a country, some organ of government (if not “the people” themselves) must be empowered to make sure that its provisions are followed. For example, if a constitution requires that all people be treated equally or that political speech can never be criminalized, but a legislature nevertheless passes a law or an executive issues a decree prohibiting blondes from discussing voting rights, who or what will have the power to strike those prohibitions down?*

The stark differences between Kelsen and Schmitt regarding the nature of law and its execution are by now fairly well known. Kelsen argued that in a constitutional polity there can be no essential difference between legislative enactments, executive edicts (including promulgated regulations), judicial opinions, and particular enforcements, since all such activities have in some sense emanated from constitutional provisions. For him, constitutions provide the “basic norms” for any polity, the fundamental conditions of legality. Since all the eventual products, from passage of a statute to putting someone in prison, are bound to involve a certain amount of interpretation, all governmental “commands” are in essence similar. From the highest court to the policeman on his beat, constitutional interpretation is always taking place, but obviously the court is likely to do a better–more careful and more impartial–job of it. Thus, when there are ultimate disputes, like that between Prussia and the Reich, it would seem to be in the country’s interest to have a high court in place to hear the cases and render final decisions.

That, of course, is not how Schmitt saw the issue. For him, it follows from the fact that since adjudication is necessarily a (usually fairly simple) matter of determining the correct meaning of language that had been intended to be clear and precise, having courts “explain” constitutional intent–something which, unlike statutes or executive edicts, are bound to be vague or ambiguous–moves judges into a political sphere where they don’t belong.

On Schmitt’s view, political determinations, like setting the range or applicability of individual rights, must be left to political entities: individuals or groups that have been elected precisely for the purpose of turning the sometimes inchoate wishes of the populace into concrete government policies. Thus, he believed that courts must be excluded from constitutional guardianship and that the choice of constitutional interpreters could only be made between the executive and legislative branches of government…or left to the people themselves. And for Schmitt that choice was easy because he saw parliaments as unruly messes of party posturing and legislative gridlock, and any mass of unled people as anarchic.

As Kelsen’s writings tend to be more abstract and theoretical than Schmitt’s, it may be surprising that his final answers to questions about which organ of government should be responsible for handling which necessary duties are quite pragmatic. He writes, for example, that “...the idea of a distribution of power across several different organs [is called for] not for the purpose of their mutual isolation, but rather for the purpose of the mutual exercise of control.” And such distribution should be effected, he says, partly in the interest of “preventing a concentration, dangerous to democracy, of all too great a power in one organ.” On why no parliament is an appropriate place for making determinations of the constitutionality of a statute, he writes, “To expect a parliament to annul a statute that it enacted…would be politically naive.” In sum, his landing on a constitutional court needs little more justification than this: “Its independence from parliament as well as from government is a self-evident requirement, since parliament and government are the very organs that, as participants in the process of legislation, are to be controlled….” This seems both eminently reasonable and not particularly difficult to grasp. What could be less “pie-in-the-sky” than this advice: “With regard to the composition of the constitutional court, which is formed as a collegial organ, one has to take care, above all, to eliminate party-political influence and to attract legal expertise, in particular in constitutional law.”

For his part, near the beginning of his Guardian book, Schmitt spends a significant space distinguishing the Leipzig Staatsgerichtshof that would hear this case from the U.S. Supreme Court, a tribunal which was, apparently, receiving a lot of attention among European polities facing constitutional crises. The U.S. panel isn’t really comparable, according to Schmitt, because, while it is empowered to make rulings pursuant to its views regarding “justice and reasonableness” on nearly any action undertaken by either the U.S. government or the government of any of its states, the Staatsgerichtshof is required to stay within quite narrow boundaries. The latter tribunal can declare a statute invalid only if it “stands in contradiction with other provisions that enjoy precedence and that the judge must take into account as well.” This court may refuse to apply an ordinary statute, but cannot “invalidate one,” because it lacks the authority to substitute its own views about reasonableness for those of an elected legislature. It can therefore do little more than “leave aside” one statute based on the existence of another one considered to take precedence.

Obviously, this attitude that an (unelected) court should be authorized to rule only on such fairly straightforward matters as conflict of laws can be used by Schmitt to bolster his claims that he, not Kelsen, is the true democrat. For, again, Schmitt’s view was that a particular elected official should be both the interpreter and the guardian of the constitution against legislative or other incursions. That is a job for the president of the Reich. Whether this position really ought to be considered a democratic one will be discussed below.

Schmitt notes in passing that, while it has been the view of some past constitutional scholars that the ultimate guardian of the constitution must be the people themselves because of their ability to resist unconstitutional government acts by engaging in civil disobedience, that seems to him not only a disorganized solution, but one that is quite likely to pose extreme dangers for those taking their chances against the might of their rulers. On the other hand, Schmitt is quick to point out that it being less risky for courts to take on their governments than for ordinary citizens to do so, is an insufficient reason to assign this job to the judiciary.

In the end, the “right” choice for constitutional guardian seems to turn on what, exactly, is meant by “the constitution” in the first place. For Kelsen, every polity is thought to, in a sense, emanate from its basic norm, a written constitution. There is no Rousseauvian “general will” in the absence of such a document. The value of a democratic (majoritarian) constitution is that it makes most people free. And while there may be some restrictions on who may participate (generally to avoid the problem of permanent minorities who will come to believe they will never get their preferences), dissent is welcome and the deliberation of both legislatures and courts celebrated.

Schmitt takes a very different position, one according to which there must always be something more basic to a state than any written document, no matter how fundamental the latter is thought to be. There is, he believes, always a positive constitution, the expression of a necessarily like-thinking, thoroughly homogeneous group of “friends.” Only such a group has the “constituent power” to create an authoritative written constitution. Any who disagree with this group (or are, say, of the wrong race or religion) are therefore “enemies” whose views cannot matter or be counted without destruction of the “positive constitution,” the ultimate basis for any polity. Therefore, only friends are to be considered of equal moral value–and thus entitled to “democratic” voice. This, of course, is a very violent picture, one in which opposing viewpoints can never be tolerated. They may be silenced by any means chosen. It is a theory according to which the spawning of an unfettered Führer who needs no aid from entities not under his control to interpret or defend his constitution should be unsurprising.

—------------ #If the impressive breadth and depth of Vinx’s erudition is not immediately apparent to any readers, I recommend they check out any of his four terrific lectures on Schmitt, Kelsen, and Constitutional guardianship available on YouTube. These talks would be worth it if they contained nothing more than Vinx’s comparison of the Weimar dispute with the Dworkin/Waldron arguments that took place a couple of generations later on some of the same issues that troubled the Weimar-era scholars.

*In the U.S., courts have issued consent decrees that have been similar to statutes and executive edicts in also having occasionally been considered unconstitutional. We should therefore not rush to the assumption that courts must be the appropriate guardians because only they will never be guilty of violating a “basic norm.”

About the Author

Walter Horn is a philosopher of politics and epistemology.

His 3:16 interview is here.

Other Hornbook of Democracy Book Reviews

His blog is here