How The Fly Got In: The Philosophy of Non-Dualism

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I don’t intend to criticize any particular theory of truth. Theories of truth are attempts to establish a distinction between true and false which transcends the mere distinctions between opinions of proponents and opponents. They are attempts to entrench the idea of truth into our argumentation. The correspondence theory is one of the oldest and most successful truth theories and like all the other ones it is not self-applicable: When a proponent of the correspondence theory says that this theory is false, if it does not correspond to reality, then the principle of correspondence is still preserved.'

'We have no problems to distinguish between true and false when we judge opinions, interpretations and descriptions of others, whether partners or opponents. But we judge them on the basis of the opinions we hold there and then – from where else should we make the true/false distinctions? This means however that distinguishing between true and false opinions, interpretations and descriptions of others is no more than judging whether these agree with our own or deviate from them.'

'Why do philosophers advocate the philosophy they do and not another one? They will answer this question by citing the merits of their philosophy and the errors, shortcomings and deficiencies of other philosophies. The response is always a retrospective one: We did not decide as realists, pragmatists, or constructivists which philosophy to study where and with whom. Only in retrospect, long after the decision in favor of the philosophy we defend has been made, do we thank our academic teachers for their influence on our intellectual development. A different university or different teachers might have been sufficient to turn us into transcendental philosophers instead of analytic philosophers, or the converse.'

Josef Mitterer is an Austrian philosopher interested in Realism , Relativism and Constructivism. Here he discusses how we are socialised into dichotomous distinctions, what these distinctions are, relativism, the non relativist presuppositions of relativism, the difference between ‘dualizing’ and ‘non-dualizing’, theories of truth, fact and fake, the influence of Wittgenstein, dualist interpretation, keeping an equi-distance to realism and constructivism.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Josef Mitterer: Still at school I had the chance to attend the annual European Forum at Alpbach, a village in the Austrian Tyrol near my home town. There I met Hans Albert, Karl-Otto Apel, Paul Feyerabend, Walter Kaufmann and Herbert Marcuse amongst others.

It was the mid sixties of the last century, I hated the confinements of my high school, the Ex-Nazi teachers, and I couldn’t wait for these three weeks of intellectual challenge to arrive in late summer. I was excited by the atmosphere of Alpbach and it was there, where I decided to put my life on philosophy.

Academic philosophy in Austria back then was hardly attractive. Twenty years after the war the scene in Vienna was dominated by a transcendental philosophy whose Post-Nazi-representatives had prevented the return of the exiled philosophers of the “Vienna Circle”.

I chose to study sociology at the newly founded University of Linz, the only one in Austria without a philosophy department. Eventually I took up philosophy at Graz University, where Rudolf Haller established a first centre of Analytical Philosophy in the German language countries. There I was able to meet Peter Winch, Stephan Körner, Brian McGuinness, John Findlay, Chaim Perelman, Gershon Weiler, Arthur Danto, Hilary Putnam, Donald Davidson and Ferrucio Rossi-Landi amongst others.

The seventies were the heydays of the Inter-University Centre Dubrovnik in former Yugoslavia, where I participated in courses with Dagfinn Follesdal, Bill Newton-Smith and Jonathan Barnes and had the chance to attend conferences of the Volkswagen Foundation with Michael Dummett, W.V.O. Quine and Bernhard Waldenfels.

When my first attempts to elaborate and discuss my philosophical ideas met with incomprehension and massive rejection I went to Berkeley hoping Paul Feyerabend would give me the encouragement to continue – which he did. Being there I did not miss out on Paul Grice and John Searle.

Eventually I got a PhD from the University of Graz. Perhaps I should mention that in those days the curriculum in Austria was extremely liberal and allowed for obtaining a PhD with very few formal obligations except for the dissertation.

I never expected a career as an academic philosopher. I wanted to live for, but not of philosophy. Seasonal work in the travel industry allowed me to philosophize the rest of the year.

I published several articles such as Farewell to Truth (Abschied von der Wahrheit ) or The King of France is Alive or Reality on the Road ( Der König von Frankreich lebt oder die Wirklichkeit auf Reisen ), gave the occasional talk and lectured part time at the universities of Innsbruck and Klagenfurt. So it rather came as a surprise when I was offered a tenure track job at the University of Klagenfurt. The department was split on whom to hire and I happened to be the compromise.

3:16: You put a central concern of yours like this: “I do not want to show the fly the way out of the fly bottle. I want to know how the fly gets into it.” Can you explain what you mean by this?

JM: In our philosophical education we are socialised into dichotomous distinctions. This education is so successful, that it’s almost impossible to retract it. Once we are caught in this web of distinctions and the problems we draw from them there seems to be no way out.

Reference-based, truth-oriented philosophy begins only after these distinctions are presupposed. I am interested in what comes before, how we get there in the first place.

Why are these distinctions tacitly accepted as matters of course , why are they beyond question and serve as preconditions for rational discourse? Are they given once and for all or are they freshly made whenever we employ them? Are they features of an argumentation technique? These are some of the questions I ask.

3:16: And what is the context out of which your approach emerged?

JM : By sheer luck and curiosity I got to know so many different philosophers early on, that I developed no desire to prefer one position over the other. Besides I was determined not to add the notorious footnotes to Plato. Often I was told the philosophical Northpole had long been discovered and we should confine ourselves to the best routes leading to it. Also that, in general, we had enough problems as it were and therefore should try to solve those already there. But then it is more difficult to make new problems attractive than to propose yet another solution for familiar ones.

3:16 : What are the distinctions that you think have been and continue to be central to philosophical discussion? And why are they problematic?

JM : Take those between language and reality, language and world, description and object, fact and fiction, perception and illusion, appearance and reality, between what we talk and what we talk about. These distinctions, these dichotomies have remained unproblematized through the ages. They are the source for the perennial problems of philosophy, such as the problems of reality, identity, truth and reference. And we protect ourselves from the loss of these problems by declaring the dichotomies a conditio sine qua non of rational discourse.

Only as long as we don’t question the distinctions as such we can discuss how their sides relate to each other. I have tried to catch the panorama of the philosophical mind, the panorama of philosophical approaches based on these dichotomies in a simple phrase: Either: there are distinctions and therefore we make them -- or: We make distinctions and therefore they are. Realists opt for the first version,constructivists and idealists for the second. There are any number of combinations of these versions into which our philosophical endeavours have differentiated and new ones are added continously.

3:16: Why do you think they are distinctions of language rather than of the world? We use language to express them of course but they’re about the world not the language, aren’t they?

JM: Sorry, but this is a question straight from the fly bottle. Idealists, constructivists and some pragmatists would probably argue they are distinctions of language and “ways of world making”, whilst realists of all sorts would claim they are about the world.However, both employ the same basic dichotomy and talk about the world and the objects therein, whether made or found.

3:16: In approaching philosophy as you do, are you inevitably a relativist?

JM : Philosophical approaches are hardly ever pure. Relativism is a combination of constructivism and realism. Realism contains constructivist elements and constructivism has a realist base – even radical constructivists don’t deny an independent reality, whether there is access to it or not. I am trying to develop an alternative to all three default positions. Yet, more often than not I am accused of being a relativist. Incidentally, relativism has such a bad name, that people are “accused” of being relativists, but not being realists.

And isn’t it weird that a strange coalition of bedfellows like Russell, Popper and Popes John Paul and Benedict should unite in condemning relativism? Relativism does have it’s perks, though: when Pope emeritus Benedict recently got into trouble for his handling, or rather lack of handling, child abuse, he instantly switched to a relativist position: what is a sin today was not a sin back then... Relativism is good as a defense strategy, realism better for attack. So whether I am a relativist or not I shall leave to those making these classifications. On other occasions I was called a constructivist, a deconstructivist, a lingual realist, a rationalist, a Hegelian, a Wittgensteinian or worse... but, yes, I claim to be a non-dualist. Is Non-dualism relativism? The reader may decide.

3:16: What do you mean with ‘non relativist presuppositions of relativism’?

JM: Extreme relativism doesn’t work. When every strike of a tongue and blink of an eye creates a new miniworld, then relativism becomes obsolete. The construction of a relativist framework must allow for a realm, a space, where relativism is suspended and there is room for (dis)agreement. All the various relativisms I came across contain these non relativist elements or presuppositions. In the introduction to “The Beyond of Philosophy” I discussed these elements in the relativisms of Wittgenstein, Whorf, Quine and Kuhn.

3:16: The notion of ‘Non-dualizing speech’ is a key idea in your thinking. Can you sketch for us, what this is and why it is so important. And what is the difference between ‘dualizing’ and ‘non-dualizing’?

JM: First, let me say, there is a terminological problem: In German I use the term “Redeweise”, in English this would translate into “Way of Speaking” or “Mode of Speaking” – so three words instead of one, and, as I use this notion quite often, it would make the English text more clumsy and less readable, especially when combined with “Non-dualizing” resp. “Dualizing”. So I settled, hesitantly, for “Non-dualizing Speech” or “Non-dualizing Mode” resp. “Dualizing Speech” or “Dualizing Mode” rather than “Non-dualizing Way of Speaking” etc. Non-dualizing Speech is a way of argumentation that does not create a dualist divide: a dichotomy between what we talk and what we talk about, between a description and the object of a description.

In Non-dualizing Mode the object of a description relates to the description of the object like a description so far to a description from now on . Every description changes the object of the description into an new object of further descriptions. Descriptions don’t refer to the object they describe, to the description so far : this is their starting base. They are not directed towards the object, they start from the object.

Dualizing philosophies turn the starting base into a reference base and the direction of thinking back to the object. They are directed backwards and lead into paradox. Non-dualizing philosophy is a philosophy of change. Dualizing Speech is trying to halt change, to perpetuate the status quo. It is an argumentation technique which operates with dualist settings and relies on dichotomies such as language-world or description-object. The cognitive process comes to a halt. The “ so far ” and “from now on ” relation is split into an “above” and “below” relation, an “about” and “under” relation. Dualist cognition operates on the basis of the language-world dichotomy: with an “above” level, where we think, describe, reflect, theorize and a level “below”, where the objects of our deliberations are lying. A little differently said: When we talk about the world the world lies under our talk about it: This raises the question, when are our talk about the world and the world in a special relation, the relation of truth... And the goal is to establish an equivalence, a correspondence between the two sides, a “1” to 1 relation.

This relation marks a central commonality of the dualist enterprise: the search for truth and knowledge.

3:16: It seems likely that from this perspective of developing a non-dualizing approach you’d want to criticize the correspondence theory of truth?

JM: I don’t intend to criticize any particular theory of truth. Theories of truth are attempts to establish a distinction between true and false which transcends the mere distinctions between opinions of proponents and opponents. They are attempts to entrench the idea of truth into our argumentation. The correspondence theory is one of the oldest and most successful truth theories and like all the other ones it is not self-applicable: When a proponent of the correspondence theory says that this theory is false, if it does not correspond to reality, then the principle of correspondence is still preserved.

Dualist advocates of truth and cognition have only two possibilities: Either they present elements of their theory as a condition for the refutation of their theory: then this theory will survive its refutation; or they employ elements of another theory for a refutation: then they have insofar already given up on their theory. When for example a critical rationalist says that critical rationalism fails if no rational/true consensus can be reached about it, then s/he is insofar not (any longer) a critical rationalist.

3:16: It might seem that this would effect the search for truth.

JM: I don’t think so. The search for truth will continue to make for a good slogan for congress openings and academic festivities and the proliferation of truth theories in the philosophical literature is still flourishing.

In the present fake news debate truth-oriented philosophers lament the absence of clear-cut distinctions between true and false, fact and fiction; they put the blame on relativism and postmodernism in general; the culprits include philosophers such as Rorty, Feyerabend, Fish, Foucault, Derrida and Butler, Nietzsche and the pragmatists not excluded. The truthers themselves seem to have no problems to make these distinctions – they separate their own opinions from those of their opponents, with truth being on their side, where else? The traditional criteria fail whenever conflicts arise: reality and its substitutes are mute and need to be represented in discourse with the help of their proponents. This leads into stalemate situations which too often are only resolved by force of various kinds.

With the increasing competition of truth-claims rhetorical book-keeping gets more and more difficult. To simply talk of facts or truth is no longer enough.

We speak of: “Verifiable facts”, “verifiable truth”, “real truth”, “real facts”, “real world” and even “real reality”, “true reality”, of “questioning the reality” and “not recognizing it”.

There is a rhetorical explosion in the discourse on fact and fake, truth and error, opinion and objectivity, honesty, lying and more. The distinctions between fact and opinion, interpretation and fiction are blurred; reality is distorted, truth abandoned, objectivity denied... it’s a mess. What more, the distinction between true and false is based on the non-distinction between true and false. If we admit that we can commit errors, that some of the opinions we hold, some of the interpretations we make, are false or erroneous – and who wouldn’t? – then we have a problem: we cannot provide any examples for false opinions we hold or interpretations we make. Of course, we can give examples for errors, mistakes and falsities we have made in the past, we have corrected and departed from. But we do not know which of the opinions we hold here and now are true and which are false and we are not able to separate them.

We have no problems to distinguish between true and false when we judge opinions, interpretations and descriptions of others, whether partners or opponents. But we judge them on the basis of the opinions we hold there and then – from where else should we make the true/false distinctions? This means however that distinguishing between true and false opinions, interpretations and descriptions of others is no more than judging whether these agree with our own or deviate from them. Our capability of distinguishing between true and false is based on the incapability of distinguishing between true and false... Truth-oriented philosophy is an argumentation technique which allows to justify any arbitrary opinions we may hold as true and discredit any opposing opinions as false or erroneous. In discourse conflicts it helps to protect one’s own views and to criticize those of the opponents. But we shouldn’t forget that we could be the other one!

3:16: Why don’t you want your non-dualizing approach to become a new paradigm? Is it possible to avoid that without either falling back into dualizing or else ending in a kind of anarchistic state?

JM: Dogmatizing a set of opinions by declaring them a new paradigm is a popular immunization strategy. Thanks to Thomas Kuhn’s Structure the revolutionary potential of paradigms goes without saying. A reputable geographer told me that in his science twelve paradigms are active at present. Paradigms are paradogmas which contain a single truth, or a set of truths, which, once discovered, must not be abandoned. This procedure in particular is supported by dualism, whose strive to secure the truth of opinions is nothing but the attempt to secure these opinions through truth.To promote a non-dualizing philosophy of change as a paradigm would be the paradoxical attempt to immunize it against change.

3:16: It seems that much of what you argue is close to Wittgenstein of the Philosophical Investigations. Is this right?

JM: His prose was too good, too powerful, not to leave marks on my writings. Austrian literature after the war was strongly influenced by Wittgenstein’s style – as opposed to academic philosophy which at least in Vienna swayed between ignorance, contempt and almost hostility with regard to Wittgenstein. I had read the Tractatus and the Investigations when I was still at school. During my compulsory service in the Austrian army Zettel was published with Blackwell and, to make it last longer, I restricted my daily reading ration to three pages; later I did the same with On Certainty. In the Introduction to The Beyond I tried to discuss to some extent Wittgenstein’s ontological “rest”, his dualist underground.

3:16: If you were to link your position to any other philosopher, who would that be and why?

JM: I chose the mottos for the 100 thesis of The Beyond of Philosophy from those I felt obliged to: Friedrich Nietzsche, who strongly advocated for becoming over being; Otto Neurath, who claimed that the separation of statements and reality is the result of a duplicating metaphysics; Paul Feyerabend who argued that cognition is not a gradual approach to truth but an ever-growing sea of mutual incompatible alternatives. He claimed that our terminology is so soaked into objectivist ideology that it must be used in a paradoxical way to describe views of a different kind. Over time I would have added authors such as Ernst von Glasersfeld, Richard Rorty, Kwasi Wiredu and Agnes Heller and replaced Thomas Kuhn with Ludwik Fleck.

3:16: Quine softened up the dualizing quite a bit didn’t he – as did Kuhn and Whorf – did they go far enough?

JM : Well, so did Kant and Vaihinger, Vico and the Presocratics, the Constructivists and Wittgenstein. They all explored the range of options within the dualist paradogma . However, none of them put the three commonalities of dualist philosophy in doubt & question ; the basic language-world dichotomy, the search for truth and the direction of thinking.

3:16: What difference does your non-dualist approach make, when it comes to interpretation?

JM: Dualist interpretation works with two levels: a text level and an interpretational level. The interpretations are directed towards the text, they refer to the text. Some interpretations are more adequate than others. The text has judgmental authority over the interpretations.

Non-dualizing interpretation starts from the text: the text relates to the interpretation like the interpretation so far to the interpretation from now on . Every interpretation changes the text to a text for further interpretation. During an interpretation, we cannot distinguish between text and interpretation. Now you may ask: But can’t we distinguish the book on the table from the interpretation on the screen? We can, but only within an interpretation of (the book on the table and the interpretation on the screen). We are always within a situation where we cannot distinguish.

Our distinctions are based on non-distinctions.

Our distinction between text and interpretation starts from a non-distinction between text and interpretation. But rather than expanding further, I dare to point readers to the article On Interpretation which serves as an interlude between The Beyond of Philosophy and The Flight from Contingency in the serialization of my philosophy on your website.

3:16: Why isn’t your non-dualism a constructivist philosophical position?

JM: I try to keep an equi-distance to realism and constructivism. However, some constructivists, especially those of the radical variety, consider me an ally. Constructivists often take it for granted that in everyday life we behave as realists, whilst we are constructivists when it comes to theory. But every day life conversations are neutralistic: they can be interpreted as naive realist or constructivist. Common phrases like “in fact”, “in reality” “in truth”, or “as we know today” simply mark the beginning of the speaker expressing his or her personal opinion.

Constructivism is an interesting version of dualist thinking, it’s a halfway house: replacing reference by self-reference leaves the traditional direction of thinking intact and opens spaces for dualist argumentation. Whether we compare our deliberations with the world directly or indirectly via comparing them with other deliberations makes little difference when conflicts arise in discourse.

3:16: Does non-dualizing argumentation lead to an escape from contingency?

JM: Why should we want such an escape? Is life, is a world, worth striving for which leaves no room for phantasy, for dreams, for hope, for change? Is the world more safe, more permanent, if we know with absolute certainty? Should we reduce the plurality of opinions towards a one and true opinion which is nothing but one’s own opinion transcendentalized? Dualist philosophers hope to escape contingency by extending the here and now into an always and everywhere. They presuppose or construct a beyond which is nothing but doubling up this world once more. Non-dualizing philosophers prefer contingency over necessity, “becoming over being” and entertain a non-dualizing pursuit of change rather than a self-congratulatory pursuit of truth . Why do philosophers advocate the philosophy they do and not another one? They will answer this question by citing the merits of their philosophy and the errors, shortcomings and deficiencies of other philosophies. The response is always a retrospective one: We did not decide as realists, pragmatists, or constructivists which philosophy to study where and with whom. Only in retrospect, long after the decision in favor of the philosophy we defend has been made, do we thank our academic teachers for their influence on our intellectual development. A different university or different teachers might have been sufficient to turn us into transcendental philosophers instead of analytic philosophers, or the converse. Three philosophical schools flourish alongside each other at a major European university, a phenomenological school, an analytical school, and one oriented to Lacan. The direction students latch on to is conditioned in part by the language they studied at high school (English?– then more likely analytic philosophy; French?– more likely Lacanian thought; German?–in the past Marxism, nowadays phenomenology), by where and from whom they get information, which lectures they happen to attend first, whether they know other, more senior, philosophy students, and so on.The circumstances leading a philosopher to defend this rather than that philosophy are contingent. Philosophers should count themselves lucky that they hold the “right” philosophical approach and not the “wrong” one, that they are at least closer to the truth than their competitors.

3:16: As a take home, do you think that your position is now perhaps more acceptable than it was when you first articulated it? Is philosophy less dogmatic about dualistic thinking than it was, or has little changed?

JM: A close friend, a fine scholar in philosophy of law, told me after I got my PhD, “now, Josef, you can admit, that what you have written in your dissertation, was all a big joke, you simply wanted to fool us.” No, I was dead serious. “The Beyond of Philosophy” was written in a slow manner, almost sentence by sentence and bags of paper went to waste for it. Almost fifteen years later, in 1992, I decided to have it published. And to my surprise the media reviewed it favourably, so did several journals, and soon there was a Polish translation. The same happened with The Flight from Contingency. So they are now both what is called “critically acclaimed” books. In Poland they were well received by philosophers who dealt with Latour, Rorty, Feyerabend and the constructivists.

In the German speaking countries the more favorable reception was in the media, communication and educational sciences. The Beyond in German is by now in a fifth edition and The Flight in a fourth. There are special editions of the journal Constructivist Foundations and the volume The Third Philosophy, Critical Contributions to the Non-dualism of Josef Mitterer, is in a second edition; there are dissertations and theses. And yet I am still very much on the fringe. Will my ideas ever make it into mainstream academic philosophy? Not very likely. But I had my share of luck, so I can’t expect the world. Yes, I would like to see my stuff published with an English/American Press at a reasonable price. Once I was as close as one can get. The executive editor of a major university press got excellent reviews of the German original, said “we made it” and I was already looking for a translator – but then the financial committee said no ... the reason given was that original work wouldn’t sell as I had no job in the U.S. I was told a book on Wittgenstein and Heidegger or similar would stand a better chance. I continue to be patient – but with my age time is running. Another reputable publisher, alas a smaller one and more semi-academic, was very interested at first, but then claimed that English readers don’t like reading numbered paragraphs and even told me “I know Wittgenstein got away with it.” ...This, Richard, is why I am immensely grateful that you made the translations of my writings accessible on your website. There is still room for improvement and a book edition may well require some changes.

3:16: And for the curious readers here at 3:16 are there five books you could recommend that will take people further into your philosophical world?

JM : I enjoy books written in a clear and simple prose, carrying fresh ideas and shaking up a matter of course or two and I could list a number of them. Besides I often get more stimulated by bad books than by good ones.

So far it is hard to find books who take readers further into a non-dualizing world, hence I dare to propose five that might take them at least further into my library: ---

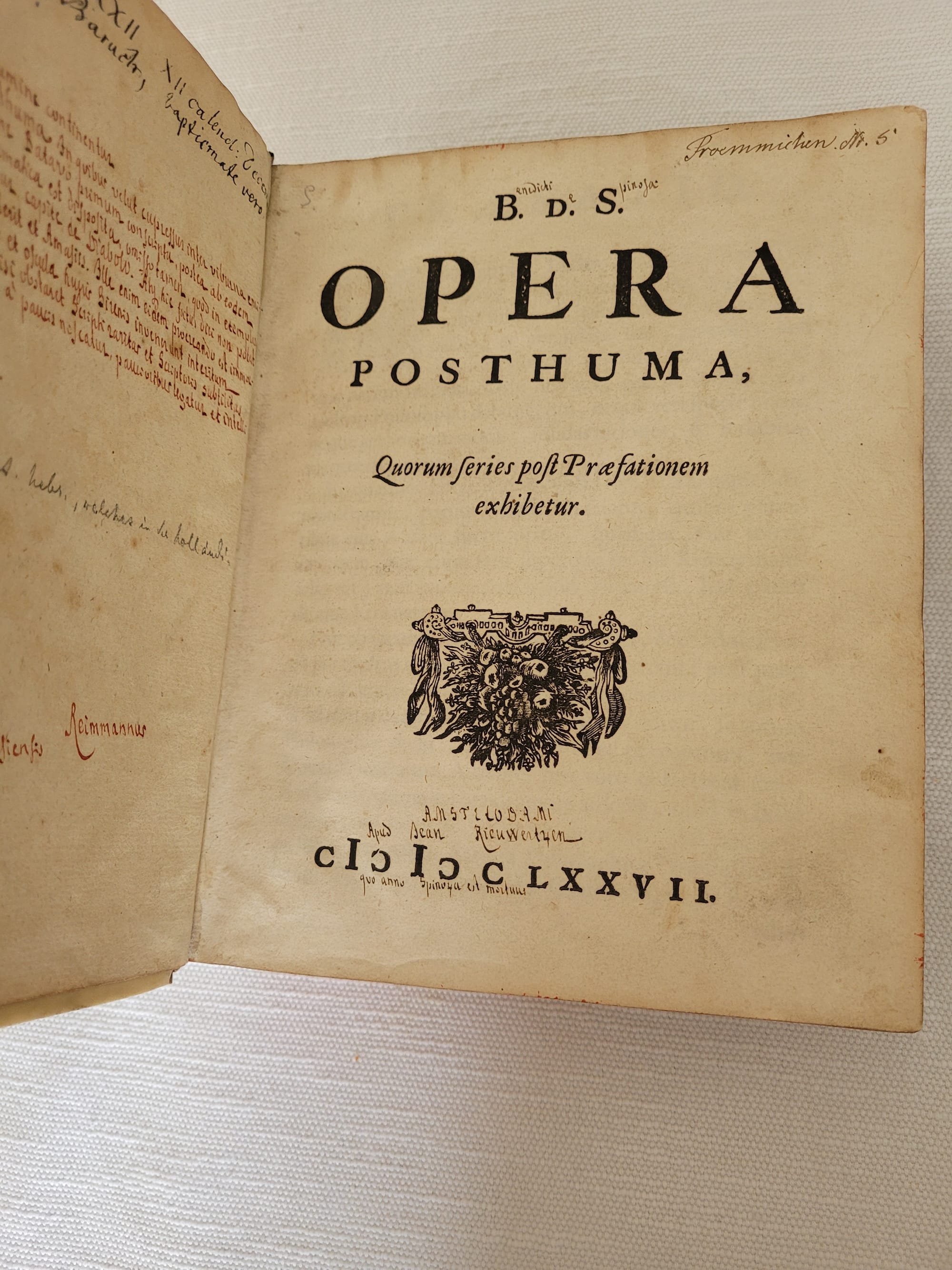

The Ethics of Spinoza from 1677. A fine copy from an Alsatian convent’s library. Spinoza turned down a professorship at Heidelberg University because it would not have given him the freedom of thought he needed. The Ethics was one of the first philosophy books I had read, still at high school. For some time I was hoping that doing philosophy could better be done outside academia, but if you try to develop a new way of thinking without academic blessings and without a professorship of some kind you are inevitably regarded as a crank or, worse, ignored altogether. ---

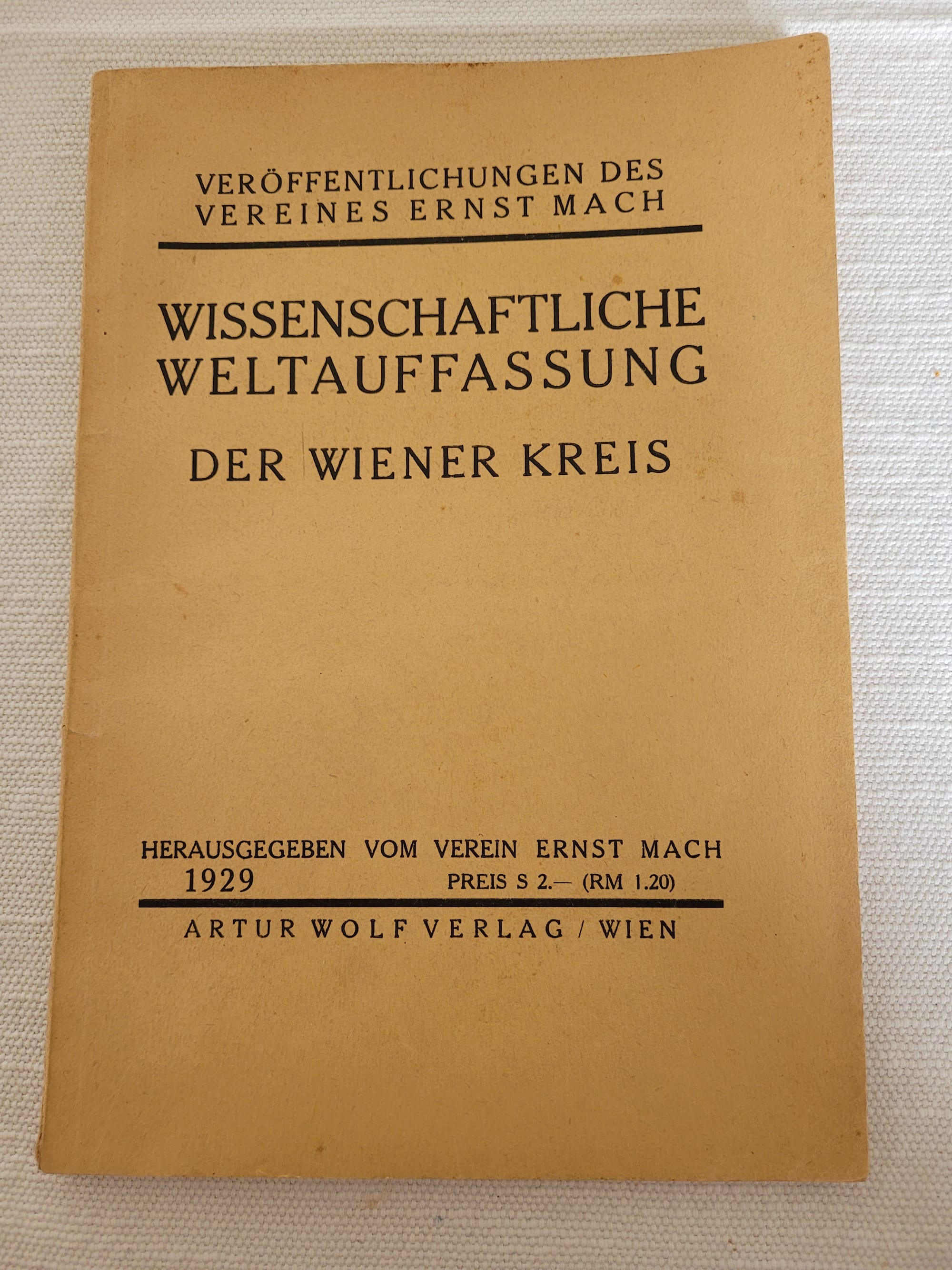

The Manifesto of the Vienna Circle by Rudolf Carnap and Otto Neurath Wissenschaftliche Weltauffassung. Der Wiener Kreis . I do have an original typescript but it has faded and is not very legible. This is a print copy, inscribed by Neurath. An original philosopher and creative social scientist, the academic world was too narrow for him, and he successfully engaged in socio-political activism. He developed Isotype, the international picture language which remains influential until today. ---

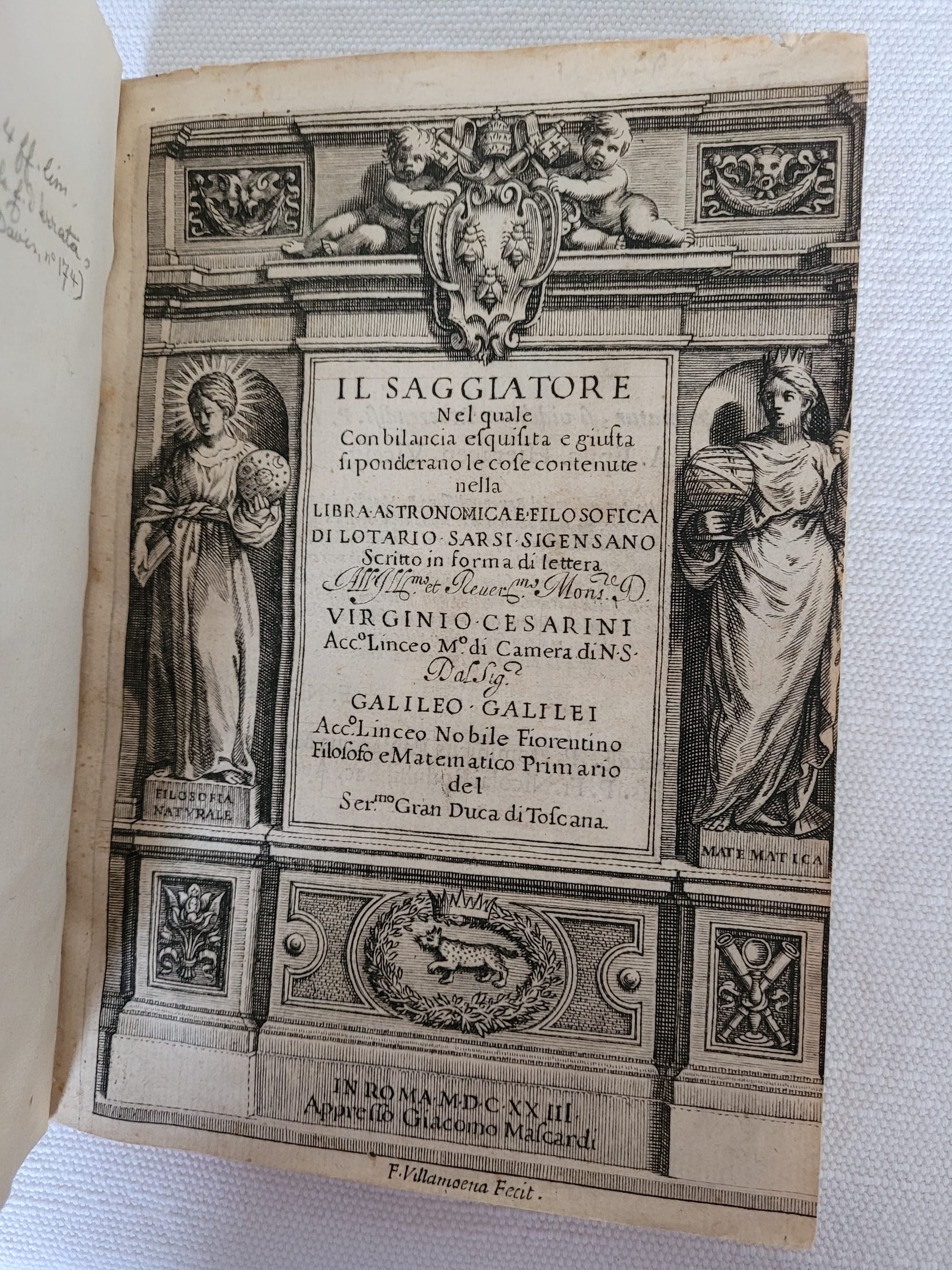

Galileo Galilei’s Il Saggiatore, The Assayer , 1623, is a first elaboration of the scientific method. Breaking with scholastic philosophy, Galilei tells us how to read the book of nature. At the time attempts to denounce him failed due to his friends at the Vatican. ---

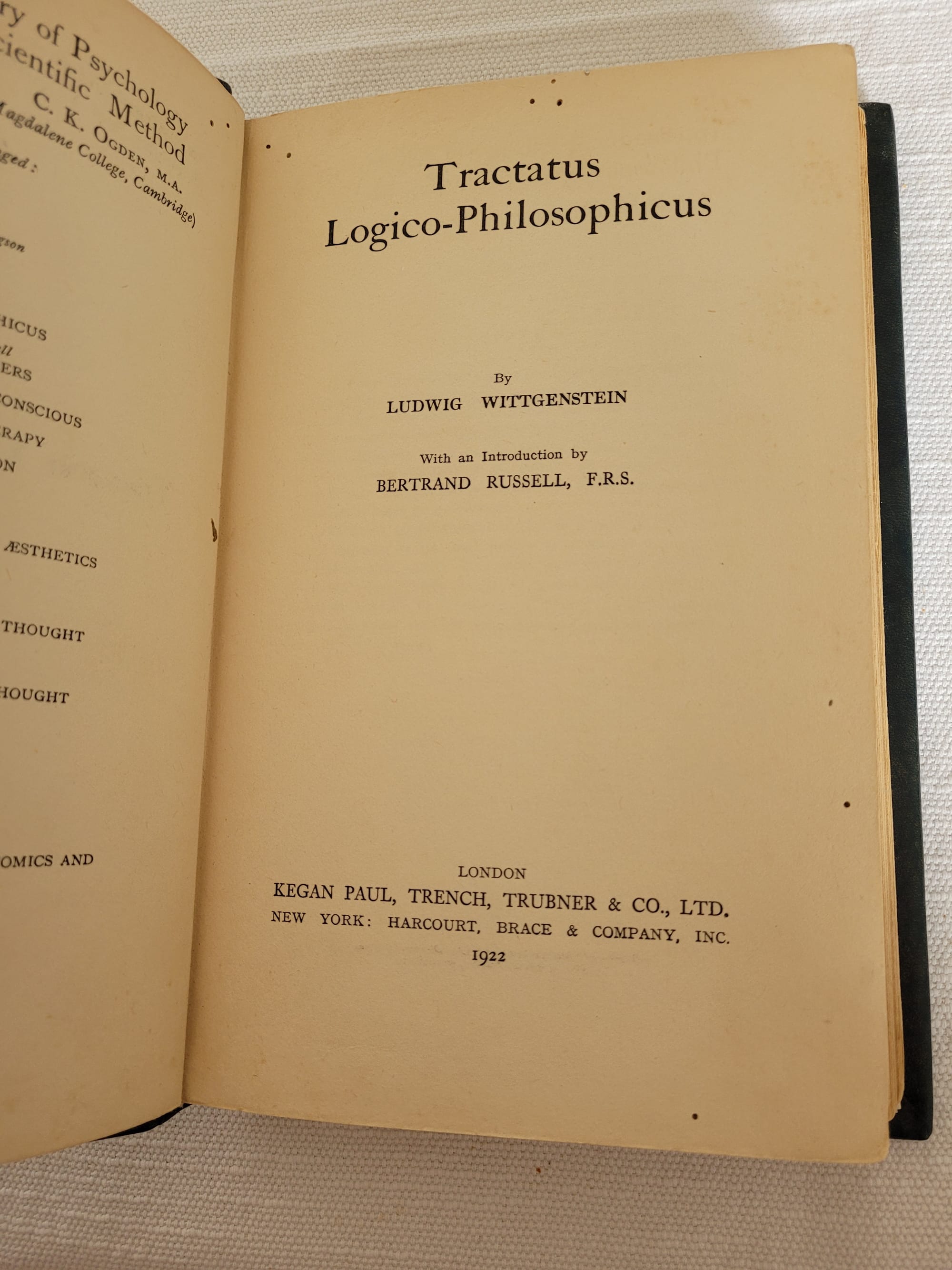

The first English edition of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus from 1922.

As soon as Wittgenstein returned from the Great War he tried to have the Tractatus published – it was turned down by the major Austrian publishers. He refused to self-finance the book and eventually gave up and sent the typescript to Russell who helped to have it first published in a flawed edition in Germany and then in a carefully corrected bilingual edition in C.K. Ogden’s International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method. ---

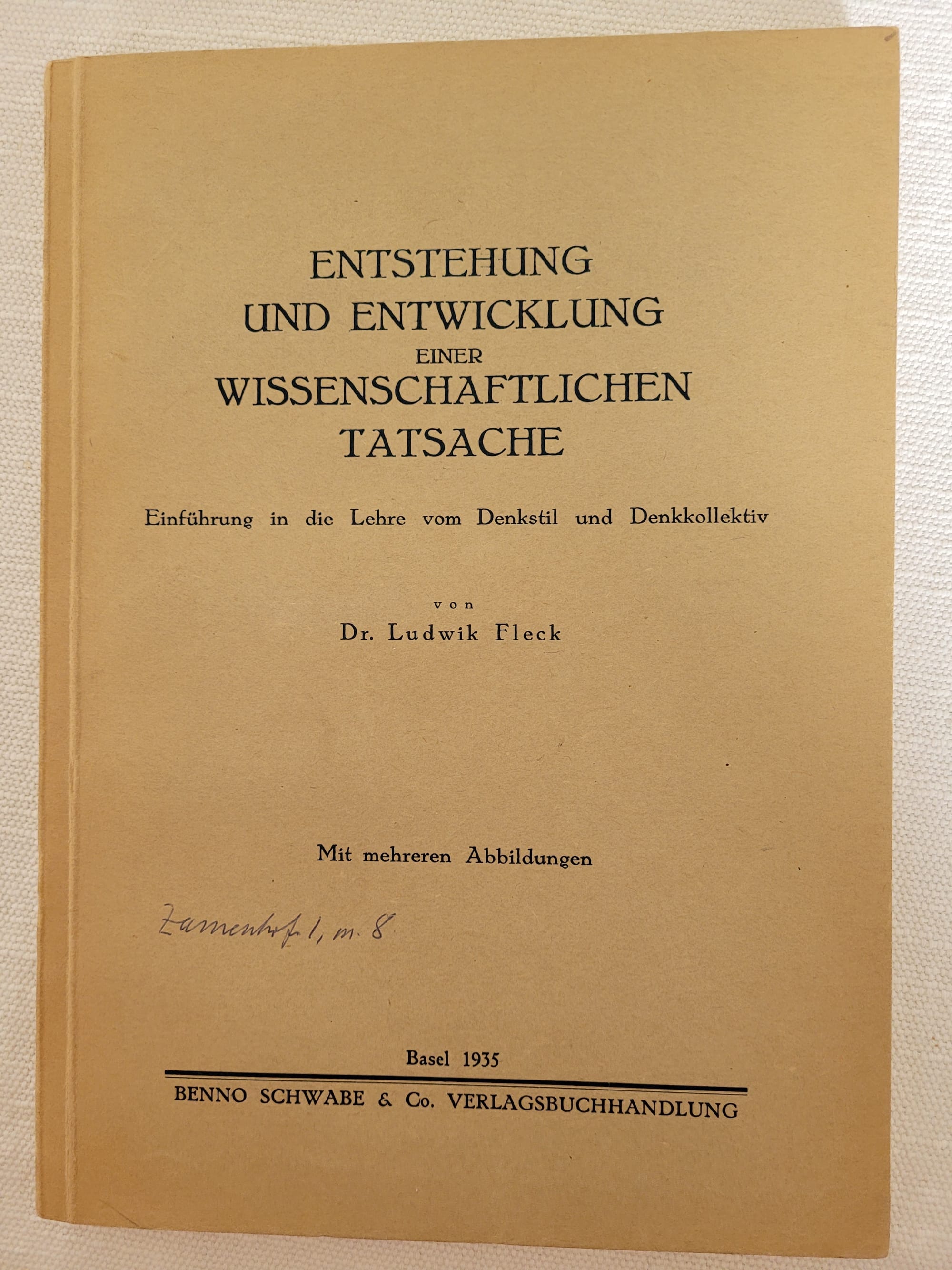

Ludwik Fleck, Die Entstehung und Entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen Tatsache , The Rise and Development of a Scientific Fact – first edition 1935, inscribed by Fleck. Reviews appeared in several medical journals, but there was almost no reaction from philosophers. The book was self-financed. He even placed a “Selbstanzeige”, a “Self-advertisement”, in the journal Philosophia, edited in exile by the German philosopher Arthur Liebert, where members of the Vienna Circle regularly contributed and, incidentally, Edmund Husserl published his famous Crisis essay. After the war hardly any copies were sold and in 1963, when Kuhn’s Structure already became a bestseller, the remaining copies were maculated. Kuhn had watered down Fleck’s ideas into a world success. Eventually Fleck was published again and got some of the attention he deserved. I tried to convince Feyerabend in Zurich that Fleck was much superior to Kuhn, but to no avail. ---

let me add Radical Philosophy by Agnes Heller. It now takes the place on the shelve where a Leibniz copy from the library of her friend Hans Jonas used to be. I wanted to present Agnes the Leibniz for her 85th birthday, but she said “Why don’t you give it to me on my 90 th ... ” which I did. Two months later, swimming in Lake Balaton, her strength left her before she could reach the shore. Her mind was as brilliant as ever, but she could no longer calculate the risks of an hourlong swim in the midsummerheat. I still miss her.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

Josef Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised

NEW: Art from 3:16am Exhibition - details here