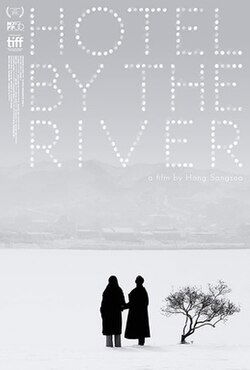

Playroom (2): Hotel By The River

'Hotel by the River (Korean: 강변 호텔; RR: Gangbyeon hotel) is a 2018 South Korean film written and directed by Hong Sang-soo. It premiered at the 71st Locarno Film Festival.'

A winter film. The screen turns white and grey. Snow falls without hurry and the river continues beneath the stillness that pretends to hold it. A hotel receives a few guests who have not yet decided to be guests. A poet has taken a room because he feels a summons from an end that does not announce itself except as a rumour of breath. He asks his sons to come. Nearby two women shelter in another room. They drink coffee that cools too fast because the window lets the outside cross a threshold they needed to hold firm. A day is given to them and to us. The day is not an argument. It is a duration that will not belong to anyone when it is over.

What happens is almost nothing. The poet waits for his sons and yet does not wait well. The sons arrive and remember old wounds with the lightness of people who cannot help increasing the weight by speaking of it. The women tend a large tiredness. The hotel has corridors that lead to rooms that lead to corridors again. There are small tables and a lobby where people pretend that passing each other does not matter. The snow keeps falling and the river keeps going. This is not description in the usual sense. It is a kind of exposure. The camera places chairs and coats where speech will decide whether to begin. The black and white draws colour out of the world so that the least movement is a statement that cannot be withdrawn.

The poet believes that death is near. No one tells him this. He tells it to himself and then tells it to others as if the telling were the event. He asks his sons to come to him because he wishes to place himself within their looking while he can still choose where to sit. They come, and once they are there, everything that could have been said becomes a long path that arrives only at small hesitations. They offer praise and they offer complaint. They speak of success and of lack. The father gives them presents that disappoint them because no object can set right an old imbalance that has learned how to live inside the body without being noticed until the moment of a gift. None of this is dramatic in the usual way. It has the mild force of family talk that goes on because to stop would be to allow silence to say more than anyone wishes to hear.

In another room two women share a retreat that is not entirely safe because the world sits in the lobby and because the world knows their faces. One of them has been wounded in a private quarrel that has left a trace on her skin. Both carry a different mark that cannot be seen but is present in the way they hold their cups and in the way they stand too close to the window and then step back. They do not come to the hotel to be seen. They come in order not to be seen, which means the camera must learn how to attend without entering. It sits still and permits the room to breathe. The talk between them is almost idle, almost comic, almost severe. The three almosts are the truth of their friendship. They do not found anything. They keep each other company and guard a small unworked space in which shame cannot organise a law.

The river is not a metaphor. It is a fact that passes alongside the hotel without asking to be included in this day. It is there to mark that continuity does not solve discontinuity. We are alive for a while and then we are not. The river does not change this. The snow helps us see the river by hiding it and by letting us imagine that movement continues even when it looks like it has been persuaded to rest. The camera returns to the bank and to the path by the water more than once. Each return is not a memory but a renewed admission. Here is what goes on. Here is what has no interest in being watched. The people in the hotel borrow a little of that indifference and carry it in their pockets like a useless token that keeps their hands from closing into fists.The poet is both dignified and foolish. He knows this. To know it does not prevent him from acting the fool with the certainty that his gestures deserve the status of ceremony. He asks for a portrait that will outlast him. He arranges his hair with a care that comes from a childhood where such care might have bought a little love. He scolds a son for not believing in his fear. He praises someone with too many words. He eats as if eating were a prayer against the fate he announces. None of these acts are large. They are the small labour of a man who would like to make the end arrive under a light that does not humiliate him. The film keeps faith with him by refusing to make him exemplary. He remains a person whose habits are equal to his thought. The two are indistinguishable and that is what saves him from becoming a symbol for anyone else.

The sons carry a friendly hostility that has grown so accustomed to itself that it has begun to look like care. Each protects his place by mentioning it as if the mention could make it more secure. One lists the work he has done and the audiences that received it. The other lists his disappointments with the accuracy of a bureaucrat of the heart. Together they want their father to decide what ought never to have been left undecided. Which of them was loved in the right way and at the right time. The father cannot grant this and he does not try to pretend. He performs his failure with a touch of humour and with a small wish for grace that the film notes and does not weigh. They all go on being together in a manner that does not heal and does not wound further. It is enough for this day.

The women move through a different weather, though they are in the same town and under the same snow. Their weather is the climate of deciding that a break has occurred and that the day must find room for kindness without a plan to be cured. They walk outside where the air stings, then hurry back to the heater whose noise protects their silence. They pose for a photograph with an air that is part teasing and part protection, as if the taking of a picture could seal an hour that might otherwise disperse. They talk about men as if men were the weather, capable of sudden changes and also capable of predictability that insults the seasons. They wait for nothing in particular and in that waiting we recognise the virtue that the film guards. They are not wasting time as failure. They are allowing time to be used up without mastery. That permission is an art.

The hotel offers a fragile public space where these two tracks can cross. A corridor joins them. A door opens and closes. A request for an autograph becomes an interruption that both parties will forget and remember at the same time. A car in the car park waits longer than a car wishes to wait and becomes a place where a stranger might be seen and might be helped without anyone announcing that help has been given. The lobby clerk knows enough to say nothing. The coffee is bitter and a little weak and therefore suited to a day that refuses to concentrate its taste. The world is present here only as what must be kept away in order for the thin relations of the day to remain themselves. This is not isolation. It is a modest insistence that a certain lightness is required if we are to remain close without owning one another.

The film does not move quickly and it does not move slowly. It moves with the rhythm of people who do not want to decide what the hour means and who therefore make their way between chairs and along paths at the pace of thought that has no object and yet feels the pressure to remain faithful to what it cannot name. The camera watches from a distance that is not indifferent. It is the distance of respect that allows embarrassment to pass through the frame without being turned into humiliation. A silence appears and is not filled because to fill it would be to give it a purpose that would shorten it and make it false. The silence does not sting. It is a winter air that you breathe carefully because the temperature will make the lungs remember that they are organs and not only metaphors.

Because the film gives itself a single day, it can repeat without losing patience. Repetition here is not a pattern for the sake of pattern. It is the admission that we live by return and that the small differences between returns are where meaning collects like frost along a window frame. The sons go out and come back. The women go out and come back. The father sleeps and wakes and then dozes in a chair because the bed has finally refused to bear him as a stage. Each return is real. The talk gains nothing and refuses nothing. The faces change as little as faces ever change in one day. We learn how to look so that the smallest tremor becomes an event. A smile has been forced and now it is not being forced. A cup is held a fraction longer than before and now it is set down with the care of a small offering. A coat is put on and does not help. A coat is taken off and does not help. The river continues.

There is a kind of comic grace that moves through the rooms like a house spirit that has learned to be kind precisely because its jokes are too gentle to protect anyone from pain. A name is misremembered. A gift is not quite appropriate and the mistake becomes a charm. A person thanks another for a favour that was not meant as a favour and a new ease arrives for a moment before pride returns to keep everyone safe. These moments do not gather into a catharsis. They are the relief by which a day can go on without turning bitter. The camera records them with the same attention it gives to the heavy admissions, because it knows the admissions would sour without these brief admissions of laughter.

There is a custom in such a film to ask what will happen when the day ends. The custom expects an answer. Here the answer is not refused so much as displaced. The end is arriving all the time and cannot be gathered to a single instant for our benefit. A shot is held a second longer than a shot is usually held. A door is closed with the care one offers to a sleeping child even when the room is empty. A path by the river bears two sets of footprints that will be erased by the next hour of snow and wind. This is the film’s way of saying that nothing is solved and that nothing has been ignored. It has seen the end without taking it from us. It has seen the middle without pretending that the middle points like a finger toward any conclusion we can use.

The poet speaks often. He speaks as one who knows that in a day like this speech will not transform anything and yet to remain silent would be to betray the day. He tells a story to a stranger with the need of a child. He tells the same story to his sons with the performance of a man who practised this very performance alone in a room for lack of another audience. The film refuses to rescue him from his words and refuses to rescue the words from him. It leaves him with the dignity that comes from being seen as he is. This is a hard gift and it is the only gift worth giving to a person who fears he has become a character in the lives of others. He wanted to command the last act. He is offered instead a view of himself standing in a lobby as if he had stumbled into a quiet stage while looking for somewhere warm to sit.

The sons learn in tiny ways. Their learning is not knowledge. It is the slight weakening of a defence that once felt essential. They move a chair and do not ask anyone to notice. They follow their father outside and carry his pride back inside without scolding. They accept each other without admiring each other. If there is a future for them that the film will not show, it is contained in these gestures that cost them a little and give them nothing to display. The camera understands this economy and spends it without calculation. A look from a son would be sentimental if it lingered. It does not linger. It falls and then it is forgotten. The forgetting is a part of what is being learned. Not every observation must become an opinion in order to count.

The women learn in a different key. Their learning is the practice of normal actions under the demand that normality not be permitted to dress itself as an achievement. They dress with care. They step into the lobby and endure the possibility of being seen by those who would like to name them. They return upstairs and find that the room belongs to them in a new way, not because they have won anything, but because they have accepted a kind of daylight that cannot be argued with. They allow themselves a brief comedy. They keep company with a silence that has shed a little of its fear. They are not cured. They are living. The film stands with them by staying close to the way time moves when bravery has no witness except a friend and a window.

When the poet asks for a portrait he is asking that the day be marked by an image that will say a person passed this way without asking that the image defend him. The picture is taken. It will be looked at by others and by no one. The act of taking it confirms that the day had a body and a face. It will not save anything. It will make nothing worse. It is a decent act and the film treats it as such. The portrait will be a small object in a drawer in a house that will be sold. That is the right size for this wish. The film grants it.

In another short sequence a poem appears as if it had been waiting behind branches for a person to come and hold out a hand. The text crosses the screen without ceremony and without claim to power. It is a light crossing, almost a mistake, the kind the world makes when it forgets it is supposed to behave like a world. The poem is not a key. It is a breath that says the day knows it is a day. It says that even when we are certain that words are not up to what has been given to them, they may still pass slowly through a frame and allow a smaller truth to stand where a larger one would fail. The film trusts this modesty and invites the viewer to trust it for the length of a line.

Snow makes every space provisional. The ground is familiar and at the same time forbids our certainty. A bench is a bench until a thin layer settles and erases the edge that once made sitting obvious. A path becomes a suggestion, then it becomes a memory, then it becomes a doubt. The film makes use of this without pointing. It lets us walk with the people we are watching. We experience the small care required to place a foot and the small relief that follows, and then we are back inside, where walls pretend to own time and where coats hold the smell of the outside in a way that can be washed away only by the coming of another season. The river does not keep the smell. The river keeps nothing. The river receives and passes and offers an image of passing that is neither comfort nor threat.

What of the role of chance? It moves through the hotel with the reserve of a person who has lived long enough to know that the greatest power is to choose not to impose. Chance allows a meeting and then calls it back. Chance makes a glance available and then closes the door with the softest click. A room number is misread and a delay occurs that saves nothing and spoils nothing and yet makes possible a small exchange later that will be remembered as something that might not have happened. The film’s faith in chance is the same as its faith in discretion. It places them on the same shelf and asks the viewer to see that what matters is neither control nor surrender. What matters is the attention that permits both to pass without being turned into proof.

There is liquor, and it loosens talk without rewarding it. There is food, and it is eaten as if eating were an excuse to occupy the mouth with something other than words. There are cigarettes that mark the time with their thin columns of smoke that look like proposals for sentences that choose to dissipate before they can harden into assertions. These are the ordinary materials of this director’s rooms. Here they take on the feel of things that have at last been accepted as ordinary. A lighter does not stand for fate. A scarf does not stand for guilt. They are what they are, and because the film keeps them there, the people in the frame are permitted to be what they are without being made to perform their meanings.

The film does not decide for us whether the poet will die soon. It places the fear beside the day and lets their relation find its own composure. The fear is not the enemy. The day is not the refuge. They are companions that agree to share a table without speaking. The sons leave and the women leave and we leave. The hotel remains for the next set of arrivals who will bring their own hours and their own restraint. The river continues with a softness that can seem like indifference until we remember that softness is often the only strength left when everything that claims to be strong has shown itself to be merely loud.

A few more scenes deserve mention because they carry the weight of what the film would like us to learn without saying it. A man chooses not to enter a room where he has been invited. He stands outside and allows hesitation to protect a dignity that could not afford the touch of another failure. A woman receives a small kindness from a stranger and refuses to make it larger than it is. A walk is taken past a view that should be admired and is not, because admiration would deny the day its right to remain unremarkable. A telephone rings and rings because no one wishes to become the person who answers. A word is mistranslated by the heart into a permission that was not granted, and the correction is gentle, and the face that made the error does not redden. Each of these allows the film to continue to honour the quiet that it has chosen as its element.

In the end there is no end except the ordinary end of light and the ordinary end of a reel. The snow is still falling when we stop looking. The images remain behind as if the room had absorbed them and would give them back later in another order that we cannot predict. We do not know whether we have learned anything. It is better that we do not know. The fear of death has been present and has not ridiculed itself. The friendship between women has been present and has not turned itself into a banner. The uneasy love of sons and a father has been kept intact without the reassurance of reform. The hotel has remained a shelter without becoming a sanctuary. The river has remained a river.

What the film asks of us is almost nothing and therefore it is difficult. It asks that we let a day be spent in our presence without our claim upon it. It asks that we be available to a kind of contact that does not announce itself as contact. It asks that we own nothing that occurs and that we be willing to let our attention be a form of giving that does not return to us as knowledge or as pride. It is a lesson that cannot be taught. It is a practice that can be kept. The film keeps it for the time it runs. We are invited to keep it a little longer as we put on our coats and step out into a winter that does not care what we have seen. We breathe and our breath appears and then vanishes. We recall a phrase from the lobby or from the river path and then it vanishes. We are left with the mild sense that what is best in us is what had no plan in that hour. We are left with the knowledge that this is enough.