Hans Falla and Janine Paulette discuss Vampyr by Louis Armand

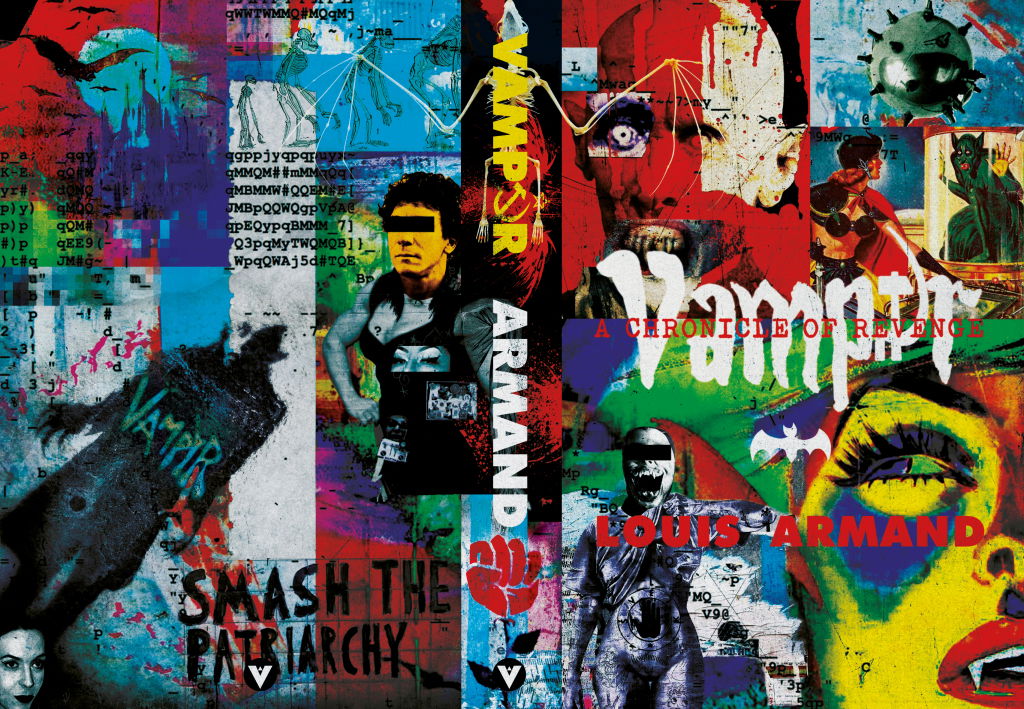

Vampyr: A Chronicle of Revenge by Louis Armand

Blurb: 'Surely this is a sign? The error is too consistent & gigantic to be ignored. One moment, History is there, replete, like cinema. The next: Void. Where purpose was, now doubt, trepidation. Something must be to blame. We are not speaking of merely vulgar misunderstandings or an emotional ambivalence. Every disappearance can only be considered a murder, caused by a hidden hand. A crime of violent omission. These accusations demand an energy of response, not bands of superstitious dilettantes. The world is not a psychoneurotic disorder. Those still living have good reason not to feel safe from the revenges of the dead, even w/ a sea dividing them. Their taboos are as a mirror held up to a guilty conscience. Originally, all of the dead were Vampyrs. Yet we do not come from the past, but from the future.'

Hans Falla: Let us be grateful to Armand who makes us happy: a charming monster who makes our souls blossom. The real writers of discovery consist not in seeking new landscapes, nor in having new eyes but rather in the mere effort to patch the writing above and against a life. Predictions of things to come are necessarily the memorising of things as they are. Armand, as he writes, is actually the reader of a kind of optical instrument he provides the reader so he can discern what he sees in himself without the book. The writer's recognition in himself in what the book says is the proof of the book's worth.

Janine Paulette: Grief is beneficial for the body, but it is joy that develops the powers of the mind. Armand is the writer who leaves pretty sci fi to the imagination. His work is a striking example of how little imagination means to us. We don't receive horror; we must discover it for ourselves inside writing that no one can take for us or spare us. His destination is no longer a place, nor a new way of seeing but a fruitless curse of a communication in the midst of solitude.

HF: Yes. His true paradises are the paradises that we have right now. If a little reality is dangerous, the cure for it is not to exist less, but to write more, to write all the time. Despair comes so soon, the moment when there is everything to wait for in his writing. We are indoctrinated into a suffering by bleeding out, so to speak. Like many anti- intellectual intellectuals, he is less incapable of a simple way than the rest. This novel is anti-desire. Possession makes it bloom. Words do not die for us immediately, but remain in a sort of aura of death which bears no relation to true life and through which they continue to occupy the book in the same way as when they didn’t. It is as though they were traveling into inner space, along with Burroughs.

Here’s a lengthy passage from which I make my initial observations:

‘Having been shaped by the industrial environment of Golemgrad, B.J. “Papa” Walt was driven to transform the physical world. His observations were not those of an aesthete seeking visual pleasure, but of an engineer of humxn souls. From his immersion in the dark arts of kapitalist production, he devised a modern alchemy that wld reconfigure the very DNA of reality. Adherence to modern technology was not, in his case, abstract. Walt set himself no less a task than the reformation of the humxn stereotype in all its minutiae. Nothing of its mould wld remain unbroken. Yet it wld be wrong to see Walt as nothing more that a commodity fetishist in extremis. All forms of existence fascinated him, in their diverse manifestations of irrational joy & suffering, of ignorance & false reason. For reason, too, in its gross distribution, is a comical affair, & Walt desired nothing of life so much as to be instructed & amused during his work of transfiguring it utterly. To do otherwise wld be like apologising to the grass that tickle one’s feet as they dance upon it, or to the mirror we oblige to produce a world in our image, gratis.

295

296

THE I=L=L=U=M=I=N=I=S=T MANIFESTO

Nyx gLand had, in the words of his more literate detractors, “the self=parodic air of Büchner’s Woyzeck.”

When not inciting ridicule, gLand was embarked upon an attempt to divine the secret meaning of the universe by a method of “excommunicating spheres.” This entailed mutating quasi=random datasets into unforeseen & Cthulhuesque forms.

“It is self=evident,” he patiently explained, “that non=communicating & non=similar spheres brought into sudden proximity will exercise an unpredictable influence on one another.”

Here was the basis of a system, even if, at times, one of mutual annihilation: contradictory elements cancelling one another out; matter & antimatter (or in the parlance of the initiated, mater & anti=mater).

But there was more to the “excommunicating spheres” than the simple appearance of a dialectics. It was a spacetime=machine built on the semantics of coincidence & superposition, of the Great Palimpsest.

That it only took a solitary genius armed w/ a text randomiser to figure all this out was somehow unforgivable. The fact was that none of the previous centuries had succeeded in even remotely imagining this one, which had failed even to imagine itself. Time had gotten away from

it, it was, so to speak, Lost in Space.

The task of the New Science, gLand proclaimed, was to

reconvene the alterior Weltgeist; to be the medium at the séance in which the void, so far adrift in the virtual, wld rematerialise in the Real.

The Old Science, in contrast, was nothing but a tawdry succession of devil’s advocates, indentured to the coming apocalypse. Those w/ a conscience to soothe dangled revolutionary carrots from a stick, always long enough to be just beyond reach.’

HF: Burroughs? Yes, good. There are perhaps no days of reading we lived so fully as those we believe we left without having lived, those we spent with a favorite as-yet un-read book. A book which changes us does not alter the image we have of it, read or unread. There is one thing I can tell you: you have enjoyed certain pleasures you can’t fathom now. When you still had your favourite book ahead of you, you often thought of the days when you had it no longer. Now you will often think of days past when you read it. When you are used to this horror that everything forever will be lost, then you will gently feel memories revive, returning to take its place, its entire place, inside you. As you read in the present time, this is possible. Armand let’s you be inert, allows you to wait till the comprehensible power restores you a little, just a little, for henceforth you will always keep something intense and horrified about you. Tell yourself this, too, for it is a kind of horror to know that you will never exist less, that you will never be unconsoled, that you will never remember less. Thanks to Armand, instead of seeing many worlds we see them all corroded into a single world no more different from the many others which revolve in infinite space, a single world which, centuries after extinction, will send us its special horror as if done by divine and insane neurotics. It’s the same source that founded our religions and created our masterpieces. It is often hard to bear the joys that we ourselves have ended and keep ending. It takes a strange strength. Armand is a muscle writer.

JP: Yes, but Armand does not receive wisdom after writing out the wilderness which everyone else can make for us, and which spares us, for his wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the wound. The wounds that we admire, the wounds that seem noble , have not been shaped by literature or cultural critics, but have sprung from very different beginnings, by evil or those realities that prevailed round them. They aren’t a struggle and a victory but rather a damned written script written, marked at least to the frustrated, because everything’s already fulfilled. The writing we love turns to ashes when we don’t walk it away from the pages. This is Armand and why his writing struts like a hooligan. The thirst for something that we already have…to keep it new, even if worse, some emotion, some sorrow; when our sensibility, which despair has silenced, wants to scribble words under guidance of some rough and ready code, begged , borrowed or stolen, that’s what Armand is signalling, even if what he writes might be broken by it. People who are not in love with reading fail to understand how we can suffer because of a very ordinary verb. This is like being surprised that anyone should be stricken with Covid 19 because a viral creature seems so insignificant. Now all words are dark, as are the bonds between ourselves and another person. Everything grows fainter and loosens notwithstanding the illusions that duped us out of love, friendship, politeness, deference, duty. Armand writes to hold on to other people, to cease existing alone. That’s why Armand’s creatures cannot escape from themselves, they know others only in their own signs and when he asserts they are lying.

HF: It’s a hard book, true. There is no one reading, no matter how wise , that Armand wouldn’t expunge entirely from his memory if that were possible. His illumination comes at the very moment when all seems found out, as if we have knocked at every sign and they open up on everything until, at last, we stumble unconsciously against the absence through which we can enter to whatever we have sought in vain all these years - and it opens up to what we had before – so the revolution, as it might have once been supposed to be, comes back as horror. That’s what’s hard in Armand, the endless proliferation of despair coded as revolt, hope, a chance.

JP: He’s a young guy. In my younger days I dreamt of possessing the heart of the world; later, the feeling of possession takes the place of dreaming. Armand reminds us that writing is a thin slice among contiguous impressions formed of a certain heap of images and he inevitably regrets every certain moment. The houses, roads, avenues are as fleeting as the books read, and written, even in our heads, that’s his warning. We cannot make reality endurable, nor fantasise such a thing, that’s another part of what this book’s about. Horror is space and time measured by pleasure. Armand takes only negatives, takes our inner dark rooms, the doors of which it is strictly forbidden to open while others are present, and then asks – are you still grinning? The constituent elements here are derived from ourselves, our experienced not innocent selves, and then spliced and diced into a discontent that mocks its own mockery. We can become different while continuing the feelings of the person one has ceased to be because our final decisions are made in a perpetual state of mind. Every new life here is merely a regret for a particular moment, and that’s tough headed and screws you up. Some parts you just want to put down and ease away from the desolation. That’s the quality I often get from him. He’s a tough guy. His writing folds its fingers into a hard place. The writing’s the bruise on a working fist.

HF: This is porn without erotica. The only true porn would be not to possess other bodies, to not perform under the eyes of a hundred universes but instead would be this sense of horrific wonder where we are threatened to die according to the everlasting word, or sign, and die continually and forever. This is what Armand’s ‘V’ is. Vampyr. A threat to be possible for ever, how beautiful that would become as the cataclysm happens then doesn’t, then does. Evermore. Negligence enlivens our desire. The cataclysm is enough to think that we are humans, and that death may come this evening in a memory so unpleasant that he would gladly relive it. And yet he entirely regrets it, because his imagination is responsible for it, not another’s book, film, even person.

JP: The book, none of it can be said to constitute a material whole, which is identical for everyone, and need only be created by the thoughts of other readers. Every reader loses everything to a great book. This book’s a kind of extractor instrument that makes it impossible for any reader to discern what, without this book, he would perhaps have already seen in themselves. To hell with imagination. I want to die in reportage. People deserve the delirium in front of them. To hell with those who want to pretend. You can almost hear Armand saying those things about the performance.

HF: Yes, I think Armand is a sort of belated social realist. He reminds me of Zola at times. In a wonderful way, it’s about wondering how you’ll find the strength tomorrow to go on doing what you did yesterday and have been doing for much too long, where you’ll find the strength for all that stupid standing still, those projects that worked, those attempts to hold on to crushing necessity, which always entice and serve to unconvince you one more time. It’s a book where destiny is laughable, and night will find you risen up, elated by the hope of more and more sordid and horrifying days. And maybe it’s predictable youth coming back, threatening the best. Too much music left outside us for death to stop for. Our old age has gone to the beginning of the earth to kill the silence of horror. And where, I ask you, can we write to, if words have no madness left ? The horror is an endless rebirth. The horror is denial. You can’t choose: horror or youth. I’ve never been suicidal except when not writing. There’s something like that in all this. Armand can show the sadness of the world has an identical way of getting to people, how it seems to succeed every time even in this most unfamiliar city he’s written out. It's always the end of dream time in Armand. Like someone said, there's no tyrant like a writer.

JP: Right. He doesn’t leave us anything to dance to. He writes to the silence of his images. It’s a world where suicide seems very appealing once you put the book down. I guess the advice is; don’t.

HF: If a book’s fat it always looks probable. This is a different kind of thing though. Not fat at all. Or, different fat.

JP: What does literature want when you can see it doesn’t ever try to give an answer? Armand just doesn’t care. I think the book marvels at those who sleep despite having trouble with their conscience. Armand writes to that kind of inevitable humane weakness. Why do we kid ourselves? Literature’s an answer to people who have too much to say to one another, who carry on, who live with frail images. Armand makes literature about nothing else. Don’t try to unload your banal unhappiness on someone else when you can read it out, do your damnedest, and wait for it to work, to keep it all, to start all over , trying to avoid any place. His writing takes hold of everything until the next time, exposes everything, each little gimmick a writer has. And in between it shakes down the boast that anyone has succeeded in getting rid of their unhappiness, because everyone knows it's not true and they've simply shelved it on a different level. Everything gets uglier and more repulsive as the signs become more visible, where you can't hope to hide their horrors and their banality any longer. In the end each feature gets marked with that hideous grimace that takes twenty, thirty pages or more to climb from out your belly to your brain. That's all we’re reading for, that and no more, for a grimace that Armand takes a word to compose. Each grimace expresses his false soul and is so heavy and complicated that he doesn't always fail in completing it. Armand finds the other level, where a sign is just a sign and everything else insomnia. If he slept properly, he'd never have written a line and I wouldn’t have been reading it. He gives what perhaps we seek throughout, that and nothing more, the greatest possible horrors so as to become fully awake before living.

HF: Yes, Armand makes us crawl back into his stuff all alone, just delighted to feel more hope than before, because he’s brought a new kind of distress and something that resembled true solitude under the guise of a renegade semiotics.

JP: Lots of writers try for that, but in the end their artistic leanings never go beyond a weakness that evaporates of its own accord. Armand isn’t groping among the shadows but calls out an alphabet which has the plain truth that’s never been really right in anyone’s head.

HF: Right. He throws away excuses for the stoniest indifference and that romantic inexperience that too often thrives as malice. Horror shows us how much is required just to keep the body at a certain agreed temperature – and it might be ok for some but there will always be exceptions. His work, all of it, asks this: take a close look at yourself and the degree of rottenness you've come to, with all your sad and comfortable images and signs and marks. He’s making out with mystery, with fairy tales; with lives that have lived this long, - however long that is - it's philosophizing as fear that’s going some place on vaginas, stomachs, cocks, snouts, and flies in the last five hundred million books as if, in the end, what we should do every time we read another book is be scared shitless.

JP: Here’s an extract – let me read it – early on:

‘In the beginning, Offensia surveys her Earthly estate. It is a recurring nightmare: skin taut across shaved paternostral skull to point of translucency, revealing a bluepurple vesicle mesh. What does she see from the abandoned bunker wherein her doppelgänger keeps its victims’ husks hung on clothesracks? At the head of a spiral stairwell, the 20/20 vision of a periscoped city in concave recession. Thus does the world come to the watcher.

Let us recommence: Offensia.

She’s walking & walking through the curfewed streets of Golemgrad. 4 o’clock under a gibbous moon. Occulted geometries of spire, minaret, stone tower. Walls of glass pierced by searchlights. The giant screen flickers, pixel=sheer of batwing, glitchgust, download artefacts from the ether beyond: premonitions of a dawn that this day or some other may not come.’

Ah, it's an dazzling thing... and being well-read doesn't help any... when you notice for the first time... the way you track as you go along ... the tropes you'll never see again... never again... when you notice that they've disappeared ... that it's all over... finished... that the story too will get lost someday... a long way off but inevitably... in the awful torrent of narratives and references... of the times and shapes... that pass... that never stop. This is the quality I love in this prose – and it goes all the way. It’s going to grind you up into battle sausage. Armand’s writing is like liquor, the drunker and more impotent you are, the stronger and smarter you are, all the better for groping among the shadows. It's frightening how many people and things there are in a past that has stopped moving. The living passages are lost in the crypts of language and lie side by side with the readers who just don't care. Inside all this is an immense hatred without stupidity. Reading it, I am easily convinced that the motives supply themselves. When you stop to examine the way in which his words are formed and uttered, these sentences are nastier and more complicated than banality. He ignores the mouth, which screws whilst it whistles, and is what we are adjured to sublimate into an ideal. It's not easy. The frenzy of Armand’s horrors persist in our present state—that's the unconscionable torture of being the reader, where reading is a disguise put on by common jumping molecules, a constant revolt against the abominable farce of a universe of writers who are all as fast as each other, all locked up inside us and by what? By damned pride. What’s this book about? Paradise lost.

HF: Or Regained. I can’t tell. I have nearly died five times since morning. Long ago is being demolished in this prose. Ballard said the future was in the 1950s. And for myself, too, many things in me have perished, even those things I thought would last for ever. Our desires now cut across one another, and splice, and in this confused existence life is inexistent; and only faux-exists in relation to our literary, artistic dreams, and they are nothing either. Everything perishes, even the hostages who follow to share our fate. And horror is somehow less bitter, less inglorious, perhaps more obliged, if we are to make reading, and art, endurable, to serve hardly any other purpose than to make unhappiness possible. Our failures spring from another kind of intellect and Armand directs us to there, not asking for new eyes but a new place to look from.

JP: Yes. I’m not sure if he’s a pessimist or optimist because he doesn’t offer a favourable outcome. But on the grounds that a writer will not succeed in changing things in accordance with our desires. In his work existence is achieved only by painful anxiety.

HF: He’s resisting the instinct to become moral as soon as one can. I end with this quote:

‘“I am anguished,” Offensia passes a hand across her brow, “becalmed. I dream only of a universe free of literature.” Such panache!

But wld the world ever for our sakes pretend to be a story (all about us)? Crudely fake, pastiched, plagiarised, impostured?

“Literature,” my mistress opines, “believes the Author is truth, whereas the forger seeks a libel more profound. The obscenity of the word itself. Not to imitate, but to embody, to become this farce in its naked being.”

And for this I am the shadow of a womxn? A womxn w/out a shadow? Both & yet neither?

What happens to the world when vocabulary runs out?

Void within void. Such fatalism bores me. I exist, knowing the world desires otherwise. That’s enough.’

JP: He’s a hard nut.