Garden Of Earthly. A Novel.

Preface: Geography

Herrenhof Lanternroot of Ashmilk Schlegelian Turnipwind Mask of the Quiet Orchard Rixdorf Boneharp Lumen Acre of the Winter Jaw Natternberg Grainshadow Organ of Soft Clay Altstadt Resinbell Fog Acre of the Bent Lattice Borkengasse Humthread Cloud Acre of the Iron Pulse Görlitz Blue Spine Acre Wortfeld Stemloom Moss Acre of the Hidden Basin Schädelrain Coalwater Acre of Grey Thread Fettleibigkeit Orchardlung Swarm Acre of Bark Thought Wechselschacht Frostroot Acre of the Slow Nerve Bentpfad Strawvein Acre of the Dust Rib Grüngasse Bladelung Acre of the Tallow Crest Steinmulde Misttendon Acre of the Grain Eye Wesselheim Boneclay Acre of the Cloud Husk Pfennigfeld Nervegrain Acre of the Thorn Loom Ebergrund Sootwing Acre of the Quiet Thread Oberwinkel Frostacre of the Whisper Jawline Unterwasen Turnipflume Acre of the Dusktwist Kranichrain Clayjaw Acre of the Lost Spool Dornstuhl Ribspool Acre of the Moss Echo Stubenflut Onionacre of the Barklit Spine Hinterhaus Lanternacre of the Threadgrain Meadow Holtmark Grainroot Acre of the Ash Bloom Schwarzgrund Foglung Acre of the Wooden Pulse Wendeschacht Resinacre of the Whisper Grain Weisenhut Nettleacre of the Cloud Thread Sensenhof Rainjaw Acre of the Cold Orchard Flockensteg Barkwhorl Acre of the Soft Jaw Weilerrest Thornlung Acre of the Dusk Vein Lehmfeld Grassacre of the Deep Bone Schrothhang Stemspine Acre of the Iron Orchard Grolzug Frostacre of the Quiet Lumen Schleusenmarkt Ragjaw Acre of the Grain Word Dreiforst Appleacre of the Ash Lung Rabenklau Strawtooth Acre of the Moss Gate Kohlenrain Dustacre of the Cloud Organ Pfarrwinkel Snowroot Acre of the Bark Pulse Silberfeld Grainline Acre of the Nerve Basin Abendquell Nightacre of the Thread Pulse Weichschnabel Mossacre of the Turnip Claw Lichtergraben Strawacre of the Bone Cloud Elendrain Cloudroot Acre of the Frost Tongue Winteracker Grainlung Acre of the Hidden Jaw Hoftreppe Rustacre of the Lumen Thread Mühlenfels Ashacre of the Quiet Bone Bärenkluft Snowacre of the Spindle Field Trichterrain Threadjaw Acre of the Grain Leaf Kelchwinkel Onionacre of the Soft Echo Lampenhain Barkacre of the Frost Lobe Wurzelweg Grainspine Acre of the Gutter Cloud Birkenloch Strawjaw Acre of the Slow Lung Hofpfad Ashroot Acre of the Twisted Grain Lumpenregen Grainacre of the Turnip Wing Dunkelfeld Mossjaw Acre of the Clay Thread Nachtschutt Ironacre of the Bark Organ Milchpfosten Cloudgrain Acre of the Bone Husk Schimmersteg Frostlit Acre of the Drift Field Brechwinkel Dustlung Acre of the Quiet Jaw Tannengrund Barkacre of the Swarm Spine Federborn Grainacre of the Mist Organ Glockenacker Clayroot Acre of the Thin Word Wiesenpfahl Frostacre of the Cloud Tether Kastanienrest Nerveacre of the Bark Field Braunschatten Strawlung Acre of the Grain Spire Schäferhang Onionacre of the Snow Jaw Weinfleck Mosscrest Acre of the Silent Thread Staubwald Grainacre of the Frost Bloom Gletscherpfad Boneacre of the Driftling Moorbard Strawacre of the Fog Lung Lenzmark Grainroot Acre of the Ash Clutch Rohrwinkel Snowledge Acre of the Quiet Organ Törfelrain Threadacre of the Grainlit Bone Dornkanzel Mossacre of the Bark Tone Rostschlucht Grainjaw Acre of the Cloud Hinge Birnenhof Frostwing Acre of the Iron Vene Geistacker Cloudacre of the Apple Spine Hartschutt Barkacre of the Slush Organ Feldscheitel Grainacre of the Quiet Shard Kohlengrund Dustjaw Acre of the Mist Organ Handwiese Strawacre of the Nerve Plume Rohrschacht Grainroot Acre of the Frost Gate Haldenkamm Barkacre of the Clay Coil Lichtmoor Grainjaw Acre of the Thin Acre Schweigerrest Cloudhusk Acre of the Grain Organ Hohlenrain Snowlit Acre of the Wood Jaw Röstfeld Grainacre of the Bark Bloom Mürrenpfad Mistroot Acre of the Quiet Vein Werdergrund Clayacre of the Frost Thread Senfenhang Grainjaw Acre of the Fog Bloom Tauerweide Strawacre of the Grain Tooth Blattwinkel Mossacre of the Iron Nerve Dornacker Cloudacre of the Ash Spine Quietrain Tallowacre of the Grain Field Murmelsee Barkjaw Acre of the Frost Sinew Kettenwald Grainacre of the Dust Organ Leinpfad Snowacre of the Bark Spindle Einzugfeld Grainroot Acre of the Quiet Acre Blaubach Frostlung Acre of the Cloud Bloom Gänserain Grainacre of the Iron Husk Hoflaub Stemacre of the Mist Coil Eisenholz Grainwing Acre of the Tallow Word Gartnerrest Barkacre of the Grainlit Thread Grabenlicht Clayjaw Acre of the Frost Grain Beutelrain Mossacre of the Wooden Jaw Unternest Grainacre of the Cloud Thread Trosswinkel Barkacre of the Ash Loop Schuppenfeld Grainlung Acre of the Frost Thread Rutensteg Onionacre of the Gutter Bone Klosterbruch Grainacre of the Mist Spindle Ulmenrain Cloudlung Acre of the Bark Coil Niedermoos Strawacre of the Frost Acre Lohnwind Grainjaw Acre of the Quiet Flood Fichtenrest Dustacre of the Bone Thread Krähwinkel Grainroot Acre of the Bark Bloom Steinpfad Cloudacre of the Soft Sinew Ufersteg Grainlit Acre of the Frost Root Ochsenrain Mossacre of the Grain Husk Lamellenpfad Ashacre of the Fog Jaw Schindelturm Grainloop Acre of the Cold Acre Federacker Barkjaw Acre of the Frost Whorl Staubriss Grainacre of the Orchard Vein Ungrund Clayacre of the Cloud Husk Blattmoor Grainjaw Acre of the Thin Acre Kornfall Strawacre of the Bone Pulse Felsmutkamm Rainacre of the Mist Coil Wehrwinkel Grainspine Acre of the Frost Lumen Tiefflur Barkacre of the Grainlit Wing Rieselrest Mistjaw Acre of the Ash Cloud Schafrain Grainacre of the Tallow Echo Birkenacker Barkloop Acre of the Night Grain Hohlfeld Cloudacre of the Thin Bloom Krallensteg Grainjaw Acre of the Fog Pulse Andermoor Strawacre of the Bark Husk Strichrain Grainroot Acre of the Frost Bloom Haldenhof Cloudjaw Acre of the Moss Acre Bultscherpfad Grainacre of the Quiet Field Falbenrest Claylit Acre of the Drift Thread Ulkengrund Grainjaw Acre of the Iron Coil Treiberhügel Cloudacre of the Frost Thread Rindenwinkel Grainlit Acre of the Dust Husk Weichfeld Barkroot Acre of the Quiet Pulse Kahlrain Grainloop Acre of the Clay Jaw Talmesser Strawacre of the Wood Acre Pfostenweg Grainjaw Acre of the Frost Bloom Wallgrund Dustacre of the Grain Spine Lenzpfad Cloudroot Acre of the Ash Pulse Hügelrest Grainjaw Acre of the Nerve Bloom Offenacker Barkacre of the Tallow Coil Strahlhang Grainroot Acre of the Fog Thread Dornfleck Cloudacre of the Bone Acre Schlehenrain Grainlit Acre of the Frost Vine Talgasse Onionacre of the Drift Acre Schmelzwald Grainspool Acre of the Bark Coil Rundpfad Cloudjaw Acre of the Moss Thread Ebenrest Grainspire Acre of the Frost Coil Waldlicht Clayacre of the Grain Jaw Hagergrund Dustacre of the Cloud Coil Faserwinkel Grainroot Acre of the Silence Husk Rabensteg Mossacre of the Bark Thread Südfeld Grainjaw Acre of the Frost Acre Flechtenrain Cloudacre of the Grain Organ Atemweg Barkjaw Acre of the Thin Bloom Zargenpfad Grainacre of the Quiet Coil Weinholz Cloudroot Acre of the Frost Acre Krugrest Grainwing Acre of the Bark Spool Stralenrain Dustjaw Acre of the Grain Pulse Kehlensteg Cloudacre of the Ash Coil Bühlergrund Grainlit Acre of the Frost Acre Dampfflur Clayjaw Acre of the Grain Woof Schmauchpfad Barkacre of the Quiet Tooth Taubengasse Grainlit Acre of the Fog Acre Steinrohr Mossacre of the Cloud Whorl Halmschlucht Grainjaw Acre of the Thin Sinew Sudwinkel Cloudacre of the Grain Coil Ölrest Strawacre of the Bark Thread Frühlingsrain Grainroot Acre of the Frost Pulse Balgengrund Cloudjaw Acre of the Grain Coil Irrenpfad Ashacre of the Mist Jaw Stollenweit Grainacre of the Bark Pulse Jochweg Cloudroot Acre of the Frost Strip Regenklau Grainjaw Acre of the Moss Thread Branntrest Clayacre of the Quiet Pulse Wurfstein Grainlit Acre of the Cloud Husk Latschenrain Barkjaw Acre of the Frost Acre Stubengrun Graincoil Acre of the Dust Spine Schleifgrund Cloudroot Acre of the Lost Husk Sternacker Grainjaw Acre of the Bone Bloom Tropfenrest Barklung Acre of the Frost Coil Tiefenrun Grainroot Acre of the Cloud Acre Flackerfeld Mossjaw Acre of the Drift Coil Krähenschlucht Grainlit Acre of the Frost Husk Rohrhang Barkacre of the Grain Bloom Hadelgund Cloudjaw Acre of the Moss Acre Überpfad Graincoil Acre of the Frost Thread Schneelehm Barkroot Acre of the Grain Husk Kluftwinkel Cloudlung Acre of the Dust Acre Brüderrain Grainjaw Acre of the Bone Coil Wachtacker Barkacre of the Quiet Bloom Talmund Grainroot Acre of the Frost Echo

Chapter 1

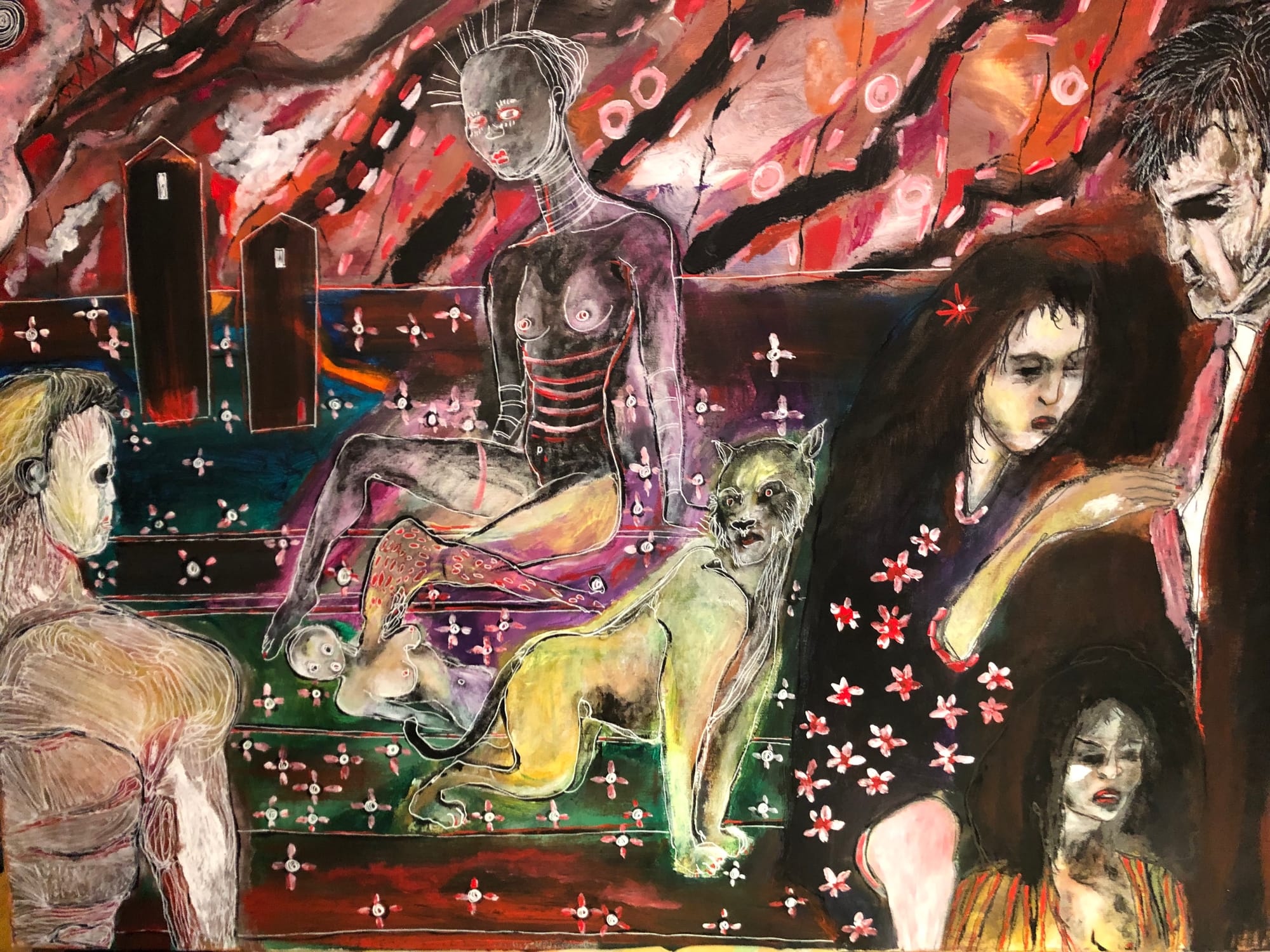

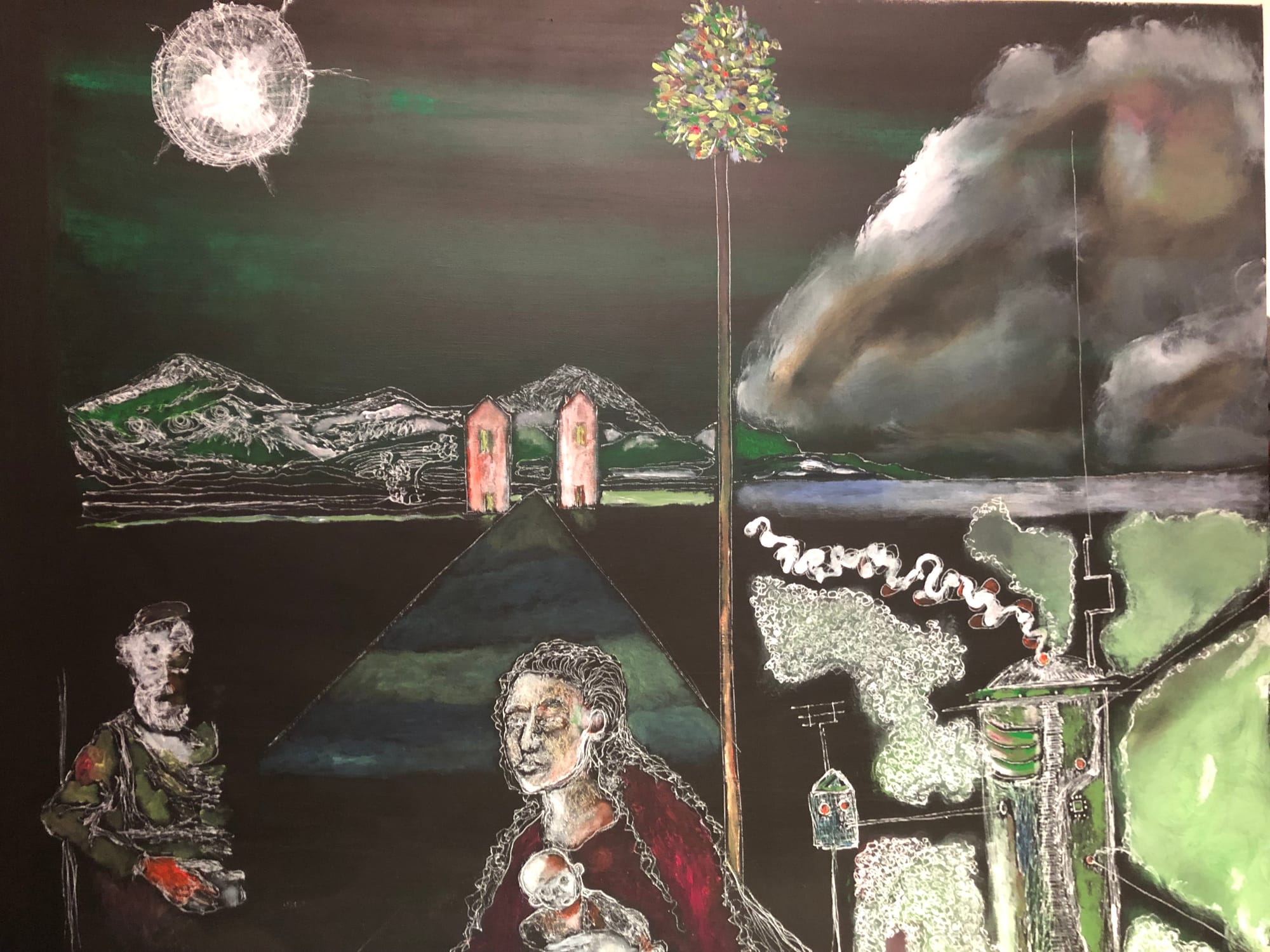

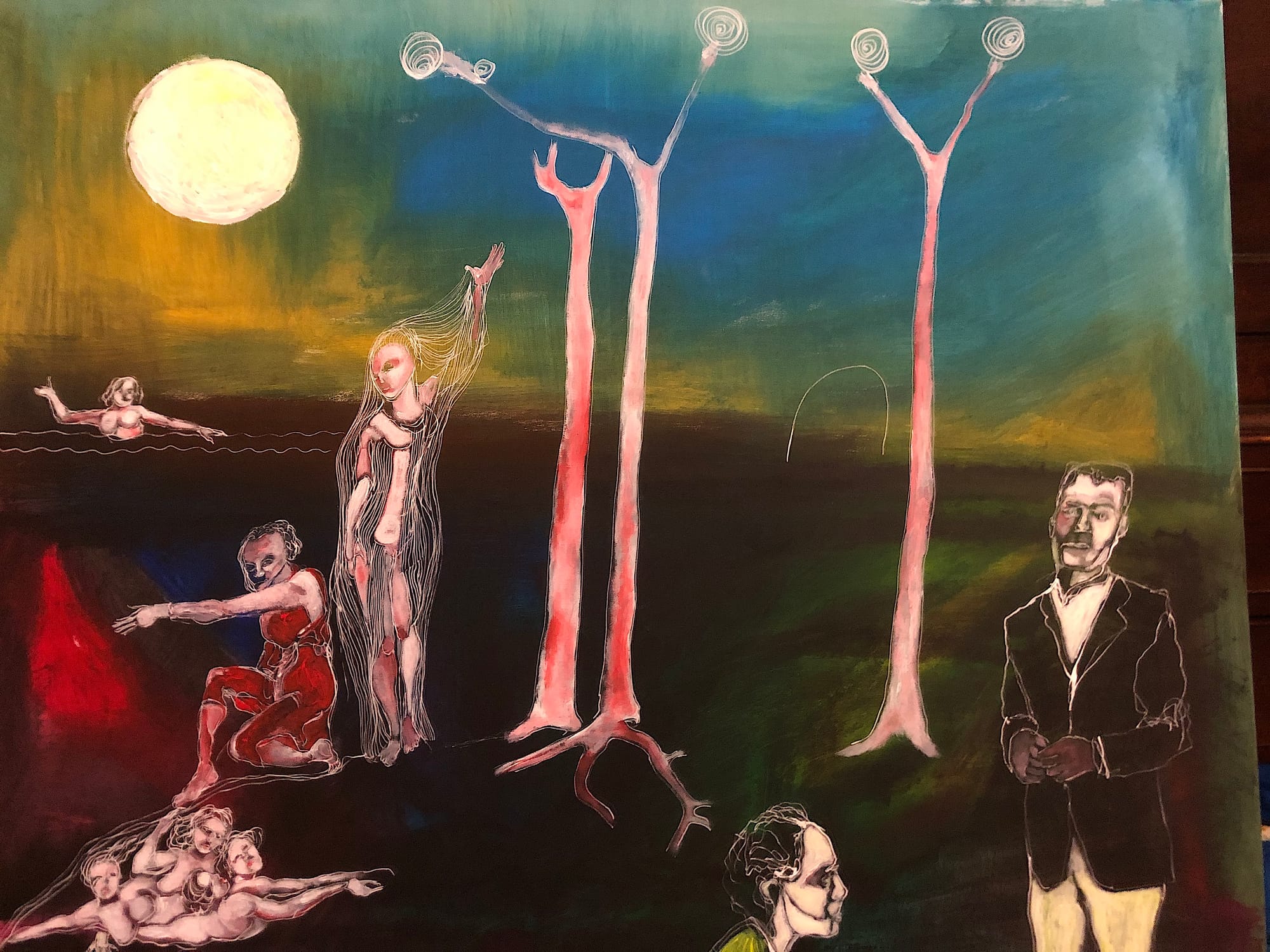

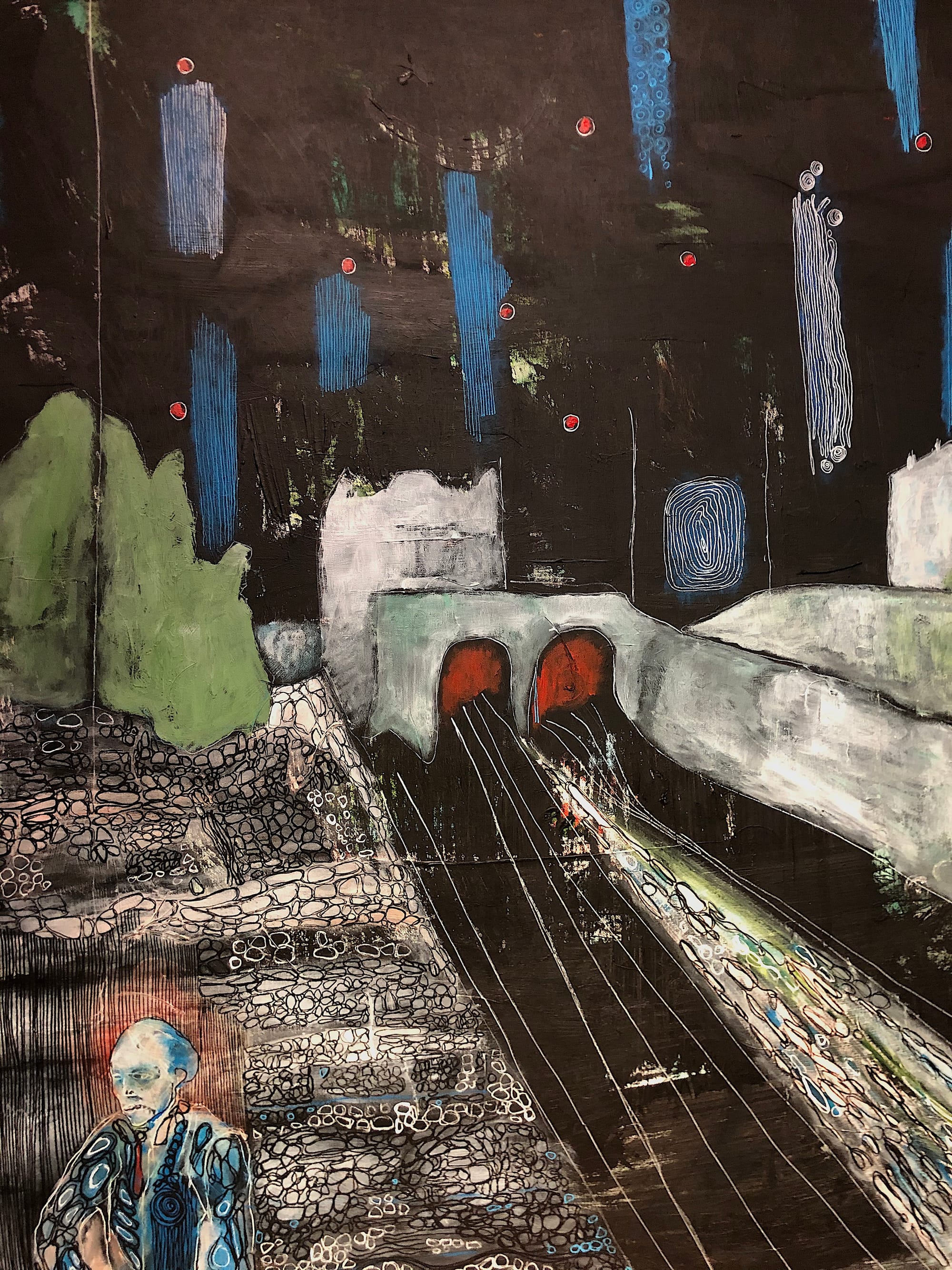

The universe began as a whisper in a mouse hole, so before there were stars there were crumbs on the floorboards of an invisible kitchen, and when I close my eyes I can feel the whole sky breathing in my lungs, tiny alveoli snowflakes collapsing and re forming in rhythms that do not respect clocks, and I say to no one that the first planet to arrive will not come from outside but will swell up under the pavement, a round dark stone pushing through the tarmac, a thought forcing its way into speech, and the old system builder from the south of the forests had already warned me, long before I was old enough to read him, that the world only understands itself when it is about to go under, so I repeat this as if it were a weather forecast, showers of meaning in the morning from the cock to the belly, scattered revelations later, thermodynamic sunsets edging the tower blocks with violet, and I see in the air not vapour but equations, quanta hopping like nervous fleas from branch to branch of the bare winter black tree bark, each transition an altar screen in miniature, each probability a tiny panel crowded with figures that look suspiciously like the creatures who crawl and grin in the paintings of the man from Bosch-Hertogen, the one who filled every square inch with birds that wear armour and fish that carry candles and men whose bodies open like cupboards to reveal other men, and I tell myself this is not madness, it is the pedagogy of the end, it is how the last days revise us, how they write in our muscles the diagram that the philosophers used to scratch with ink on paper, and while I am thinking this my stomach growls like a small unphilosophical god, demanding its daily sacrament of cabbage and stale bread soaked in broth, and I remember that the world spirit, if it ever visited the market, would come disguised as a potato seller with mud under her nails and huge tits, and I would not notice, I would be too busy counting the angles of the clouds, looking for that exact bent light which proves that the vacuum is crowded with virtual particles, and I say aloud in the empty room that when the last planet arrives it will not explode into us, it will lean very slowly against our roofs like a neighbour, it will press its cratered cheek to our brick and tile and our beams will creak as if remembering something, a conversation in an alien dialect of gravity, yet the people in the street will go on frying onions and haggling over turnips, because the end of the world is never televised in their language, it is just another pressure in the joints when they kneel to scrub the step, and if I listen carefully to the molecules in the steam above my tea I can hear them rehearsing the argument, they say, you think we are random but we are your biography, every Brownian twitch is a syllable of your name, you would see it if you wrote yourself down in integrals, and I nod, though no one is there to see, and I start to preach to the peeling paint on the ceiling, telling it that the cosmos has already finished, that we are only the echo, that the bright curve of history which the old Swabian traced with such exact and merciless patience has already returned to the point it began from, and now we are nothing but commentary, marginalia scrawled in pencil by a drowsy student of eternity, and in the corner, where the plaster has fallen away, I see a tiny painted scene as if the wall has remembered being a panel in a triptych, a little town burning, a river turning to serpents, a man with the head of a bird pushing a wheelbarrow full of clocks, and I know, with the same dull certainty with which I know the price of onions on a wet Tuesday, that my own skull is already part of that landscape, that one day the mice will walk through my eye sockets as if they were archways in some ruined monastery, and the stars will be only a rumour they hear in the rustle of old newspapers, and at the same time, absurdly, I worry about whether there will be enough flour tomorrow to bake bread, I calculate in my head the rate at which the last sack is being used, grams per day, crumbs per mouse, and I think that perhaps this is what it means for the absolute to be poor, to live always between the equation and the onion, never entirely at home in either, always smelling faintly of both chalk and cabbage, and the rain begins again, fine and slow, a drizzle that looks from this angle like the downward drift of lost probabilities, each drop a collapsed waveform, each puddle a failed universe, and I start explaining to the invisible listeners that in the beginning the world did not know it was beautiful, that is why it produced those grotesque gardens where saints stand among knife faced fruits and musical instruments turn into torture devices, because matter was trying out all the shapes it could imagine, it had not yet learned the modesty of the cabbage, the discipline of the potato, but now the situation is reversed, now every vegetable on my plate is a philosopher, the carrot knows more about necessity than any lecturer, the beetroot, when sliced, displays cross sections of the dialectic in its rings, and I lecture them all, fork in hand, that the final secret is not hidden in a cathedral or a theorem but in the way the knife passes through the fibres, the way the cells surrender without protest, as if they had been waiting precisely for this moment of division, and my tongue picks up the salt and says silently, yes, this is the movement from abstract to concrete, from concept to stew, and I laugh, and the laugh sounds slightly deranged in the narrow room, but I go on, because there is no one to interrupt, and I tell the dust on the windowsill that when the last day comes the equations will not be cancelled, they will be completed, the terms will balance like scales in a medieval painting, angels on one side, frogs on the other, and the coefficient of suffering will finally be reduced to its simplest form, but we will not notice, we will be busy arguing about the price of coal, and somewhere the great painter of nightmares will be calmly adding another tiny figure squatting at the edge of a pond, perhaps this time it will be me, hunched over, muttering about quarks while a fish bites my toe, and above me a night sky freckled with sterile moons, each one the failed copy of an idea that once thought it could be real, and my blood, sluggish in winter, will still be performing its own liturgy, red cells carrying oxygen as if it were contraband through the checkpoints of my capillaries, white cells patrolling like minor bureaucrats, and I will think, even as I cough, that here inside this damp chest a dull version of the cosmic drama continues, the struggle of form and formlessness, of order and decay, and I will want to shout to the cobweb in the corner that this is important, that the cobweb must understand that it too is an illustration of the logic of things, but I will only manage a wheeze, and the cobweb will go on catching small flies who dreamed, perhaps, of more illustrious destinies, and I will shuffle down the stairs and out into the alley where the air smells of frying fat and wet stone, and the sky above the crooked roofs will be a grey palate waiting for some hand to smear crimson comets across it, yet nothing happens, except a dog barking at nothing, so nothing from nothing, imagine, at last, ha, and I tell myself that this barking is the negative moment, the pure refusal without content, the sound that clears a space for any meaning to enter, and I grind my heel into a patch of slush and think of how many times the world has already ended, quietly, in the heads of thinkers, in the midnight fevers of mystics who saw in a cracked jug the sign that all forms are breaking, and I feel almost cheated that our own ending seems to involve so much queuing, so much small change, so many lists of groceries, and I say in my most solemn inward tone that perhaps this is exactly right, perhaps the universe deserves to conclude not with angelic trumpets but with shopping bags, not with a horseman in armour but with a woman counting coins for potatoes while the multiverse trembles, and in that moment a gust of wind flings a scrap of newspaper against my leg and I see, in the blurred print, words that look like fragments of lectures I once heard about the self seeing itself, about history examining its own skull in a shattered mirror, and I start again, from the beginning, telling the invisible mice and the cracked teacup and the damp coat on its hook that the ultimate truth is that nothing is outside this room and yet everything is, that the diagram which the old philosopher drew with such painful care across thousands of pages is now hiding in the blue veins on the back of my hand, in the broken plaster, in the way the rainwater feels cold then warm as it seeps through the shoe, and that soon, very soon, the planets will fold their orbits like chairs at the end of a fair, and the quantum fields will power down like exhausted stage lights, and all that will remain will be a faint smell of cooking and the echo of an unrecorded sermon about cabbages, probability amplitudes and the sorrowful joy of being the last poor witness of a universe that finally, reluctantly, learned to think so thus and thus I sit again in whatever chair this is, the metal cold or lukewarm depending on the weather that seeps in as a fine grey drizzle or a sheet of blank white sky that presses down on the roofs of Kröhlstrasse and the crates outside Donner’s tobacco shop and the oily puddles near the tram line, and in my head the same old problem turns around itself like a dog checking whether the floor is worthy, finally, of sleep, this question of how the whole fits together, how history and lungs and the faint ache behind my left eye when I have not slept properly can belong to one intelligible movement instead of being scattered like receipts for cabbage and soap across the table, and I remember that man from Stuttgart, or was it Tübingen or some other damp fucked over place with stoves that never quite warmed the corners, who insisted that the whole is only itself at the end when it has gone through all its shapes and chewed its own ratty bleeding tail, and I think of him while the coffee machine wheezes and spits, and the air smells of burnt beans and wet wool and tired commuters, and my fingers, little vertebrates in themselves, stiffen around the cup, the skin creased, epidermis over dermis over capillaries humming with erythrocytes that carry oxygen from the wet November air I dragged in through the alveoli, and each red cell is a tiny courier in a system that pretends to be rational, with valves and nodes and silent muscular contractions, a whole monarchy of tissues, and still my stomach complains in its dull peasant way that all this talk of the absolute is fine but where is the bread, where is the sausage, where is the potato soup that steams in chipped bowls in the back rooms of Schlegelgasse, where Lena’s shop sells onions and yesterday’s rolls and a cheese that smells like old books, and I count coins in my pocket, stupid metal universals, abstract labour rattling against lint, and the sky changes, it always changes, low cloud in the mornings when I drag my body here, liver processing whatever nameless toxin I picked up from the cheap schnapps at Meister Renz’s, his bottles lined up mute theses along the back wall, each label a promise of clarity that never arrives, and I sit and read the same few pages from that thick volume by Beiler or Beissen or whoever they say understood the Swabian better than he understood himself, and all I hear in those tidy paragraphs is that everything must somehow be necessary, even this cracked saucer, even the way my right knee grinds as cartilage erodes year by year by year, even the faint mildew in the corner where the ceiling meets the wall in this nameless cafe that has had so many owners, old Frau Hartwig with her watery eyes and her habit of counting change twice, then the brothers Dietrich who tried to sell lottery tickets and thick cigars, then quiet Soraya who painted the back room blue and filled it with plants that drooped like students in late autumn, and I stuck myself in her for a while a brief wetness that caught in the golden light soaring and soaring ah and all of them, all of us, are meant to be moments of one world that is busy becoming itself, like a joke, all jokes, this joke, that joke, I can imagine, I can imagine if I close my eyes, the water too dense, her rough hand scratching at my swollen cock then my back and yet when the wind slaps the window I just feel the draught on my neck and the grit in my teeth and the way my nails grow whether I understand them or not, keratin sheets pushing forward from nail matrix, blind insistent cells dividing in the darkness, whether I understand them or not or anything else, and somewhere in the city men argue about constitutions and trade look at their blue rimmed faces they all want it, never for one minute expect anything else from them, their pilot lights glowing, pink, purple, spiders on the ridge of their dying and living and pools of sweat, an angle, she rutted to the time and now ask whether Müller & Söhne will extend credit on paper or insist on coin, and somewhere else a child coughs in a narrow bed and little cilia in the trachea wave like grass in a storm, and all of this is meant to make sense together, the fog on the river, the ledger at Fink’s paper warehouse, my own stupid heartbeat, systole diastole, and the thought that knowledge, real knowledge, is not just cataloguing the pieces but seeing the necessity that binds them, and outside it begins to snow or rain or something between snow and rain, a half formed decision falling from a sky that cannot quite commit, whether I understand it or not or anything else, and I think of systems, and will one day position myself so they will feel my betrayal, there will be money involved of course, the way they promise shelter, whether I understand them or not or anything else, a roof against contingency, and how they are built from sentences laid one upon another, bricks from the yard at Schuster & Sohn, rough edges abraded, nice word that, fired in the same kiln, all terracotta theory, and still the wind finds a crack and whistles through, and my scalp itches, sebaceous glands overproducing, microscopic mites trudging through the forest of my pubic hair, and the waitress, is it still the same one as last year, I no longer know, they blur into one apron with different hands, different tired eyes, she brings the latte and I thank her with a voice that sounds to me like it belongs to someone somewhere else, come, come, some clerk who believes in wages and Sundays, and I watch the swirl of milk on the coffee surface, little galaxies of fat and water, molecules bumping in Brownian idiocy, and I tell myself that the mind is meant to rise from this, that there is no other material, that the synapses in which my idiotic thoughts of unity and history and necessity fire are made of the same carbon and hydrogen as the table and the stale pastry under the glass bell on the counter and I would put out my hand and cop a feel of her juicy hind in the rain and am a stale perversion, and I think of the man from the southwest, not by name, that would be too simple, but as a weather system, as that long low front of thought that rolled across Jena and Berlin and whatever other towns sold cheap ale and cold rooms with wobbly desks, a man whose own stomach must have growled and whose own bowels must have squeezed out excrement in the early mornings while he prepared to talk of the absolute movement of self mediating rationality, and I picture the steam of his shit rising in some cramped privy while outside students argued about the French, about freedom, about whether the Kingdom of Württemberg would ever pay them on time, and I feel a kind of obscene consolation that even the highest system sits on a pile of bones and muscle and digestive tract and that somewhere in my small intestine villi are absorbing sugars from the cheap bun I ate walking here, these sugars entering the bloodstream, fructose, glucose, the very fuel of speculation, whether I understand them or not or anything else, and outside the rain turns to sleet and back again while the years fold into each other, one winter like another, here then gone, here then gone, here then gone, one landlord after another at the boarding house on Sternweg where I fall asleep with books on my chest and damp socks on the floor, my breath condensates on the window, tiny droplets coalescing into rivulets obeying laws I never bothered to learn, surface tension, gravitational pull, the same laws that hold the planets in their hard indifferent ellipses while I rummage in my coat for the last coin that will buy me a thin slice of ham from old Jütte’s stall near the river, and she wraps it in paper already smeared with some stranger’s grease, and her fingers are cracked from brine and cold, and she complains, not about metaphysics, but about the municipal tax on market spaces, about the way the inspectors from Albrecht & Co come with their forms and their pens and their smug little smiles, and I nod and think, yes, institution, civil society, all of this belongs, but I say nothing more because my tongue is busy feeling the roughness of a broken molar, enamel chipped, dentine exposed, nerves fluttering like frightened birds when cold air touches them, and the sky that day is yellowish, a sickly colour that sits heavily on the tiled roofs of Nitzschgasse and Pardauergasse, and the bells in the church I never attend ring out a time that could be any time, because the years blur, and the snow comes late or early, and in some seasons the river floods and stinks, and in others it shrinks back and shows its muddy ribs, and through it all I keep circling the same thought, that the truth of anything is never that private little thing in front of you but its place in a story, and yet whenever I look up from the printed pages all I see is condensation and people with bags of turnips and cheap flour, and the reflection of my own face in the window, nose red from cold, eyes bloodshot, scalp flaking slightly, dandruff constellations on the collar of my coat, dead cells falling like imperfect snow, and perhaps that too belongs, perhaps the concept must shed its own skin, and I think of synaptic pruning in the young brain, those early years when the nervous system builds too many connections and then ruthlessly clips them, a gardener cutting branches so that the tree will grow in some coherent form, and I wonder whether history does that, whether systems of thought are just gigantic acts of pruning, killing off wild shoots, declaring some paths irrational, and I picture the philosophers as gardeners with filthy fingernails and sore backs, lugging compost in barrels bought on credit from Ketterer’s yard, and the wind rises again, always the wind, always the weather undermining the claims of the concept, draughts sneaking in under doors, muscles tensing involuntarily to preserve warmth, shivering as little rapid contractions produce heat, ATP consumed, mitochondria panting in their microscopic thousands, and somewhere a printer’s shop on Adlershofstrasse runs out of ink, and the apprentices curse and wipe their hands on their already filthy aprons, pigment and oil ground into their cuticles, and the owner, Herr Kraus, worries about prices and subscribers and the rumour that someone in Leipzig is preparing a cheaper edition, and all that economic fretfulness is meant to be comprehended in one vision, and I sit with my cup and feel a bubble of gas move through my gut, absurd little pocket of air shifting along pink convolutions, and I suppress it, tighten the anal sphincter like a good citizen, not wanting to fill the cafe with the stink of my insides, and I think, it is ridiculous, it is fucking ridiculous, that we talk about spirit when we are sacks of meat trying not to fart in public, and yet perhaps that is the grandeur of it, that the universal has to pass through this, through me and my worn shoes and my stained fingers and the faint fungal itch between my toes from cheap boots and damp socks, and year after year I come here and the coffee is sometimes thin and sometimes strong, depending on who is at the grinder, and outside sometimes there are protests and sometimes funerals and sometimes nothing at all, just drizzle and the shuffle of feet, and the names of the dealers and the streets change or repeat, Wessel & Baumann takes over where Levy & Sohn failed, and the sign is repainted and the credit terms silently altered, and young men with ink still fresh on their moustaches talk loudly about revolution or about the profit margin on hemp, and the old women with scarves tight around their swollen necks talk quietly about arthritis and the price of potatoes, and my ears, full of little ossicles beating in sympathy with every crash of cup and spoon, keep registering it, turning vibrations into nerve impulses, hair cells bending in the cochlea, ionic gates opening and closing, and all this electrical noise runs up into the same greyish mass behind my forehead where somewhere a sense forms that there must be a pattern, that these noises, these weathers, these bills from H. Blenheim & Co for candles and coal, cannot be merely scattered, and in the evenings, when I trudge back along Friedrichsplatz or Marienwinkel, past the butcher’s where a pig’s head stares blankly from the window, its eye cloudy, its snout rosy and slick, and the air smells of blood and sawdust, and the sky is either violet or black or a flat consumed orange behind clouds, I feel my bones complain, osteocytes entrapped in their mineral prison sending who knows what slow signal of wear, and my breath plumes in front of me, and I think that I too am part of this slow labour, this long years long movement of a mind that knows itself only by losing itself in people who think about the price of cabbage and the composition of bile and the direction of the wind on the river, and some mornings it is early spring, or later, or some undetermined slice of year when the trees along the canal at Kantsfeld or Fichtestrasse show little green eruptions at the tips of their twigs, chloroplasts stirring, photons being harvested like gossip at the market stalls, and my sinuses run with thin mucus, histamine released, vessels dilated, the body reacting to pollen or dust or the mere idea of change, and in the cafe the light comes in at a different angle, flatter or fresher, and the table where I sit shows its scratches more clearly, each groove a record of some previous hand, knife, spoon, each scar in the wood soaked with varnish and spilled drink, layers of use like layers of commentary on the idea that everything is connected, and I think of the old names of the towns, of dealers in second hand folios, like Reuter & Lamm, who sell brown spotted volumes that smell of mould and mouse droppings, and inside those volumes neat Latin letters talk about causes and substances and first principles, and the pages are freckled like my own forearms, melanin gone rogue in small patches, and my heart sometimes beats too hard, an extra systole, a skipped beat, some arrhythmia that makes me briefly dizzy as I stand up, orthostatic hypotension probably, blood pressure dropping, baroreceptors in the carotid sinus firing, sympathetic nerves scrambling to tighten vessels, and still I reach for the book and for the cup, as if these small gestures were part of an enormous, blind rhythm in which the city, the weather, the sweating workers in the printing house, the civil servants bent over files at the Rathaus, all participate, and there is no need to know it, no need for them or for me to say the word that would name it, because it goes on whether I mouth the syllables or not, and sometimes, walking past the fields at the edge of town where coarse rye and beets grow in poor soil, I feel the mud suck at my boots and hear the crows, black thoughts hopping on brown furrows, and I see peasants bending their spines, hands knotted around hoes, clothing patched and patched again, and their breath steams too, filled with microdroplets that might carry bacteria from one lung to another, and beneath their feet earthworms move blindly, aerating the soil, and fungal mycelia stitch root to root in networks older than our codes and laws, and somewhere a clerk at Heidenreich & Neffe writes out an insurance policy against fire or flood, the attempt to rationalise contingency, and I think how each premium paid is one more piece of the puzzle, one more effort to make the irrational calculable, and my own body meanwhile collects small injuries and repairs them in silence, macrophages engulfing debris, fibroblasts laying down collagen, scars forming where once there was smooth skin, and the weather shifts again, a sudden gust rattling the shutters of the cheap boarding rooms in Hintergasse where the drunken students sing at midnight, and thunder rolls like a thought too large to fit into any single head, reverberating between tenements and chapels, and lightning forks over the chimneys of Mörikehof, discharging heaven’s static accumulation, what bunkum, shit, nitrogen fixed in the air, raindrops fattened with whatever dust was up there, falling onto laundry hung between windows, onto the notebooks of children walking home from school, onto the bald spot growing slowly on the crown of my head, keratin sparse there now, scalp shiny, melanocytes tired, and I remember that none of this is free, that the coffee I drink is imported, carried in holds of ships owned by cunt men whose names I will never know, insured by companies with double barrelled titles like Grünwald, Peters & Söhne, roasted in a warehouse by a man with calloused palms, thin cock and a cough, distributed by carters who smack their horses on grey mornings, and all of that labour condenses into the bitter liquid that wets my tongue, its molecules interacting with taste receptors, sending signals through cranial nerves to some cortical area that stupidly says this is good or this is bad, and I think that the grand movement of the world must look like this, tiny contacts, ions crossing membranes, merchants haggling, clouds forming, snow melting, prices rising and falling, children learning to read, peasants emigrating, cells dividing, old men dying of congestive hearts while their legs swell and their nails thicken, and that there must be some point at which this ceases to be a chaos and becomes a story, some invisible dealer of meaning, not located in any street, not paying taxes to any bureau, who takes these fragments and arranges them, and as the years slide across each other with the soft shush of banknotes changing hands at Abendroth & Fils, I find that my own spine curves, that my gait shortens, that the handwriting in my notebooks trembles, alpha motor neurones misfiring, myelin thinning in unnoticed slow catastrophe, and still I come to the cafe, or some cafe, for they blur, and the same cheap wooden chairs, the same chipped cups, the same smell of overboiled milk and underwashed floors receive me, and the sky outside is sometimes a hard blue that seems to deny all interpretation, and sometimes a low grey that invites projection, and the pigeons peck at crumbs near the tram stop, their feet red and scaly, their heads bobbing, cortexes the size of peas containing whatever passes in them for certainty, and porn is just a gist of somewhere else, a sequenced arrival of a dimming spirit, one episode then another hardening then not, hardening then not, lessening and lessening, draining away some and adding to others, watch and watch, masturbating alone again, on and off, on and off, I know nothing except that I am here again with a book that tries to tell me how the world manages to be one thing and many things, and in my bloodstream platelets patrol, ready to clot if a vessel tears, and in my gut bacteria digest fibres I cannot handle alone, and at the market on Rosenplatz they sell cabbages stacked like green brains, leaves veined and layered, and the traders shout, and the clouds pass, and the prices change, and my own thoughts, such as they are, such as they can be in this patchwork of weather and hunger and worn cloth and late rent notices from the office of Binder & Krause, keep circling back to the sense that somewhere, not above but within, all of this is trying to say something, that the sleet and the aching joints and the smudged print and the coins smeared with the grease of a hundred hands belong to one slow, grinding utterance that began long before I sat in this chair and will go on long after I leave my last mark in the dust of whatever street this is, and the sky, whatever it chooses to do, rain or sun or that blank indifference of low cloud, will go on being the ceiling of it or some ragged version of a beginning I am standing in the drizzle am drizzling thinking that must have drawn electrons as little saints with beaks and lanterns, crowding along the edge of an energy level like pilgrims on a crumbling bridge, and the rain itself is a kind of quantum register, every drop a collapsed possibility trembling on my skin, and there are cherubs made of probability amplitude, round faced and badly behaved, pushing one another out of orbit while the sky hums like an accelerator in a barn, and I tell myself that if I stare hard enough at the cloud cover I will see the wave function of history, not the polite textbook one ja ja ja but the crooked, worm eaten one that describes how a thought in Jena or Stuttgart or some other place with wet roofs and bad coffee turns into the flashing sign above the butcher’s on Haymmarkt, and I think that the old wood panels in the grocer’s on Dilthey Lane, where the apples lean into rot and the potatoes sprout pale arms, are just diagrams of this, brown and green diagrams of a field that does not care about me, and I feel the wind change direction in my lungs, the bronchioles tightening a little as if the air of the day had opinions about method, and on another morning or the same morning shifted by years the clouds are higher and the light comes in sideways and I am muttering about two ways of reading anything at all, the sky, the pavement, this greasy pamphlet from the second hand dealer Haering on the corner, and one way is to treat it as if it were talking to me now, loudly, in the present, about my own mess of problems, so every grey streak across the river is a remark about my tendency to postpone decisions, stop putting everything off you cretin, you’re a coward, always too fucking scared to make a move, a moron and a coward and a fucking lousy low life scum coward Kunt and the other way is to sit in the rain like a careful undertaker and say no, this belongs to another time, the puddle has its own century, its own dead, the pattern of ripples has to be placed back among cobbles long since lifted, and then I realise that either way I ruin it, I either shove my own concerns into everything like a drunk ventriloquist with a wood cock, one eyed, Cyclops of pine or blind blind fate, or I turn the world into a museum where even the mud has a caption, and somewhere between these two botched habits there is supposed to be a better way of walking to the market without lying to myself, but I do not find it, I only find the damp scarf around my neck and the slow ache in my left knee and the feeling that my red blood cells are tiny archivists pushing oxygen to synapses that no longer trust themselves, and the weather keeps changing in a way that is never quite seasonal, a snow that feels like late thought, a heat that arrives like an unfootnoted objection, and the shop signs fade and are repainted but they always bear the same surnames, Henrich and Frank and Waibel and Stamm, dealers in books, dealers in onions, dealers in the cheap meat that sits grey in the window until the afternoon dogs begin their bargaining, and between their stalls I try to decide if I should read the old philosopher as if he were buying cabbages with me, right here, squinting at the price of the carrots, or whether I should lock him back in his century and say he had his own mud on his boots and his own wars and his own worries about being paid on time, and whichever I decide I can feel the mistake crawling over my skin like midges, I can feel my epidermis shedding flakes of error onto my scarf, my nose dripping with some overworked metaphor about relevance, and the air tastes of coal and wet stone and a little sausage fat from the stall at the corner of Haymstrasse, and I remember that the pamphlet says the philosopher hated being turned into a contemporary puppet, that he would have despised having his lines rewritten for the sake of making him agreeable to our current academic diets, and yet here I am chewing his pages like old bread while the wind pushes grit between my teeth, so I stand there and count my breaths, each inhale full of dust spores and exhaust and the faint perfume of the woman ahead of me who is buying turnips, and each exhale a small, private declaration that there must be some way of respecting the strange otherness of his problems without letting them fossilise, and while I think this my stomach growls in a thoroughly unphilosophical way, a muscular wave along smooth tissue, glands squirting acid into an indifferent cavity, and I remember I still need to buy lentils and flour and maybe some of that cheap cheese from the stall with the chipped blue counter, because the week is long and the money is not, and at the same time a part of me is still up in the clouds with saints, painting halos on quarks, insisting that the unseen architecture of this market, this city, these damp lungs, is metaphysical, not in the sense the clever ones now prefer where everything is quietly reduced to a vocabulary lesson or a sociological survey, but in the sense that there is a claim here about what is real, how it hangs together, what counts as a whole, and I feel an unreasonable loyalty to that thought, as if the cartilage in my joints were made from his stubbornness, as if my synovial fluid had absorbed his refusal to let the big questions be shamed into silence by polite empiricism, and the clouds above the tram stop look like thick white paragraphs that no one wants to admit are still being written, and yet below them the trams rattle past on schedule, the children kick at piles of leaves that have been swept into tidy metaphors by the city workers, and Rosenkranz the fishmonger slaps a dead carp onto the scale like he is ending an argument, and I think about non metaphysical readings of any old system, how every generation tries to wash the blood and thunder out of it, to say it was never really about what there is, only about how we talk, or how we agree, or how we share reasons, and I feel a flicker of temper, a little rash of anger across my forearms, the capillaries brightening as if to say enough of that, enough of the neat stories that take out the one piece that still has teeth, and the wind picks up round the corner of Beiserplatz and throws grit into my eyes so they water and sting and I mutter oh for fuck’s sake into my scarf, because I am tired, my liver is busy processing the stale beer from last night, the villi in my intestines are harvesting whatever vitamins they can wring from cheap bread and boiled cabbage, and still I am supposed to decide whether the big old system on my shelf is alive or dead, relevant or obsolete, friend or embarrassing uncle, and the more I think in those terms the more absurd it seems, like asking whether the spinal cord is relevant to the fingers, or whether mitochondria are still contemporary inside the muscle cells of my thighs, there is no outside here, the questions about freedom and law and community and mind and matter are the same questions that shape the way the butcher ties his apron, the way the woman in front of me shifts the weight of her shopping bag from one hip to the other, the way the pigeons on Dilthey Bridge organise themselves into a miserable grey democracy,

Chapter 2