Existence and Consolation

Interview by Richard Marshall

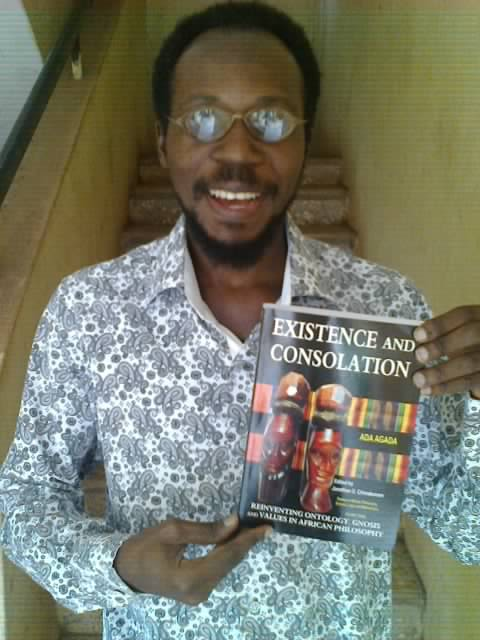

Ada Agada is an upcoming Nigerian philosopher and one of Africa's brightest intellectual prospects. His groundbreaking work in African philosophy, Existence and Consolation: Reinventing Ontology, Gnosis and Values in African Philosophy was named a 2015 Outstanding Academic Title Award Winner by Choice the magazine of the American Association of Colleges and Research Libraries (ACRL).

3:AM: What made you become a philosopher?

Ada Agada: It was Aristotle who located the promptings of philosophy in wonder. No doubt wonder motivates the intellectual process. But we cannot downplay the role of inspiration in energizing wonder. I made up my mind to become a philosopher at the age of twenty after reading Plato’s Republic for the first time. I told myself that here was a majestic spirit. I thought I could aspire to the kind of greatness Plato attained. However, my final decision should be seen as the culmination of a philosophical interest that started earlier. I was struck in my mid-teens by the realisation that the moment-to-moment maximisation of the emotion of joy was all human existence consisted of. Even in my maturity, this fact still strikes me. The question I asked myself after reading Republic is this: is it possible to transform this perception of the place of emotion in human life into a thoroughgoing philosophy? This question led me directly to the African philosophical synthesis, that is, consolationism.

You’ve been credited with reinventing a thoroughly African episteme, one that makes a complete break with European epistemology. The history of African philosophy has been contentious and full of fascinating controversies since the 1920s so perhaps we should start by asking you to say where you situate your work and thinking. Kwasi Wiredu argued that pre-20s philosophy wasn’t real philosophy and Paulin Hountondji defended traditional ethnophilosophy against the ‘professional philosophy’ of Wiredu. You argue that if African philosophy is going to be a tradition in its own right it has to move away from foundations in Greece but at the same time has to be universal in a way that ethno-philosophy isn’t. Am I right in saying this? What is African philosophy now, where does it come from and is it progressing?

AA: Actually, Paulin Hountondji is a rabid opponent of ethnophilosophy. Hountondji and Wiredu are among the founding fathers of modern African philosophy. They launched the tradition as an academic discipline. You are right about my view of African philosophy. My colleagues at the Conversational School of Philosophy (CSP), Calabar, share my view that for African philosophy to be taken seriously it has to find some sort of foundation within the African thought-world rather than in the Greek or European thought-world. Not all African philosophers accept this position. Some are so carried away with, and perhaps intimidated by, the success of Western philosophy that they will pooh-pooh the idea of ethnophilosophy supplying an authentic African foundation for African philosophy. Unfortunately, they are faced with the dilemma of doing either African philosophy or merely ‘philosophy in Africa’, the latter being a euphemism for Western philosophy. Again, we at the CSP have realised that if African philosophy is to contribute originally to humanity’s philosophical heritage, African philosophers ought to bring something new to the philosophical roundtable, otherwise whatever the universalists may call ‘philosophy in Africa’ (apology to Hountondji) will go down in history as a mere footnote to Western philosophy.

At the same time, ethnophilosophy obviously is not conceptually rich enough and systematic enough to take African philosophy where it ought to be. I sympathise with the position of the particularists who see in ethnophilosophy a wellspring of authentic philosophical ideas. The devastating critique of universalists or modernists like Hountondji and Marcien Towa has left many African philosophers shying away from even using the term ‘ethnophilosophy’. They think that it connotes primitive thinking, prescientific thinking. I think these philosophers miss the point. Ethnophilosophy can remain relevant to African philosophy as a wellspring of ideas even as it is transformed through individual innovative thinking to a truly universal philosophy. This is what I tried to do with consolationism in my book Existence and Consolation. Ethnophilosophy is important, as the Zimbabwean philosopher Fainos Mangena has noted, but it cannot be the terminus of African philosophy as Mangena seems to think. It is rather a wellspring of ideas, as Bruce Janz has suggested.

On the matter of progress, African philosophy has undoubtedly made serious progress. Since the publication of my book in 2015, I have counted more than twenty major publications that are pace-setting in magnitude. Some of these works are edited volumes. South Africa and Nigeria have emerged as focal points of African philosophy. South Africa has the added advantage of a well-developed educational sector and well-funded philosophy departments. The CSP scholars are overcoming the research impediments in Nigeria and continue to be pathfinders. We have very bright stars like Jonathan Chimakonam and upcoming ones like Victor Nweke and Aribiah Attoe. Interestingly, we have developed a method of philosophizing dubbed conversationalism which we hope will help push African philosophy towards greater rigour, innovation, and systematicity. We have noted the urgent need for system-building. Unlike Western philosophy whose great systems were constructed long ago, African philosophy is starting from scratch. We must build our own systems regardless of contemporary developments in Western philosophy. We may borrow from the Western analytic and continental traditions, but we must not be beholden to Western philosophical methods.

3:AM: Consolation philosophy is the name you give for this alternative constructive program. Can you sketch for us what Consolidation philosophy is and where it comes from and what it draws on both from African thinkers like Senghor and Asouzu but also European thinkers like Kierkegaard, Unamuno, Heidegger and Sartre?

AA: Good question here, good question. Some philosophers have found my choice of label intriguing. A few have asked me to distinguish my sense of ‘consolation’ from Boethuis’ usage. I used the term in a very original way. I picked ‘consolation’ specifically to underline the fact that I was constructing a philosophical system that seeks to describe a deterministic universe, where determinism is subsumed in what I call universal fatalism (simply, inevitability). Consequently, consolation philosophy tries to answer the question whether the universe is pointless and whether the existence of the human being, as a special kind of entity, has any meaning. Answering this question led me to the keen awareness of the inadequacy of strict determinism and freedom (free will). Both notions, I realised, imply a perfect universe, and by perfection I mean the absence of evil both in thinking things and non-thinking things. Indeed, a perfect universe would be one in which there are no yearnings, no strivings. Consolationism submits that a perfect universe is impossible and that in a universe of yearning, such as the one in which humans find themselves, rationality emerges out of emotionality. Consolationism submits that a universe that exists for a reason which the human mind can only speculate about is a tragic manifestation of yearning. One may say science will someday be advanced enough to crack the riddle of ‘being’, but we must agree this is a remote possibility. Of course we can respond to the absence of certainty by telling ourselves that we are already here, that it does not matter if we do not know why we are here or why there is something at all, that it is enough to be born, to eat, grow, reproduce, and die. My philosophy has already accounted for this ‘unemotional’ attitude as merely consolation. For me, then, human existence, and indeed the existence of the universe itself, is consolatory. Everything is a consolation. It is the mind that structures the seeming meaninglessness of existence. In this structuring lies human consolation. Human comportment is fundamentally emotional, regardless of our high-level intellectual orientations, activities, and goals.

What I actually tried to do with consolation philosophy is recast the question of being in terms of mood – reasons, feelings, and attitudes rooted in a primordial impulse. Instead of asking myself what ‘being’ is in the Greek way, I asked myself what ‘mood’ could possibly mean. I considered the notion of being and non-being inadequate and overly Western. Yes, I was determined to produce a philosophy that is not Western in content. Senghor became a factor because his ideas on emotion and reason provided me with an epistemological compass although I acknowledged the error of Senghor in attributing emotion to Africans and reason to Europeans. I felt that Senghor was trying to unveil what I call the melancholy being, the human being who defines their intellectual projects from an understanding of themselves as emotional beings. Any philosopher who keenly observes human behaviour at all levels will not doubt my point about the closeness of the emotional and the intellectual. I thank Senghor for supplying me with this insight. As for Asouzu, he inspired me with his method of complementary reflection which conceives reality as a fragmentation of a complete picture and asserts that the goal of all thinking is to unify these fragments in the struggle to recover the absolute unity. Asouzu’s work in African philosophy encouraged me to push on with my project. African philosophers hardly attempt to build systems. While writing my book, in isolation from the Nigerian academia, I must say, I often dropped my pen and wondered whether I was doing the right thing. I thought I was taking a responsibility too big for me, a young unknown thinker without institutional affiliation. Asouzu’s belief that African philosophy sorely needed system builders kept me going. My country Nigeria is an English-speaking country. So, the analytic tradition dominates philosophy departments. But I was lucky to read English translations of thinkers like Kierkegaard, Unamuno, Heidegger, and Sartre. I immediately felt a kinship with them, having instantly seen similarities between their existentialist phenomenology and consolationism. However, my early introduction to analytic philosophy enabled me to avoid the obscurantism one finds in Heidegger and Sartre. I hope to engage more with the Western analytic philosophers in the near future.

3:AM: What is Innocent Asouzu’s notion of ‘complementary reflection’ or ibuanyidanda philosophy about and how has that been important to your development of Consolation philosophy?

AA: As I noted earlier, complementary reflection recommends an inclusive vision of reality. Complementary reflection is the epistemological vehicle of ibuanyidanda, an Igbo term one can translate as ‘complementarity’. The dominant thesis of ibuanyidanda philosophy is that all existent things are missing links of reality. The closer these missing links the more complete is the picture of reality we paint. Even the scientist understands this idea very well. Asouzu’s concept of missing links persuaded me that universal panpsychism is the logical conclusion to the profoundly complementaristic and communal worldviews of Africans. I think Africans are more communal, more group-emphasising than Westerners. The Easterners or Asians are more like us. But I am digressing! As you can see, panpsychism is an important topic in my book. I hope to clarify my kind of panpsychism in a future work. I am already writing papers on this subject.

3:AM: How do categories of Power and Glory work better for the African lifeworld than those of omniscience and omnipotence found in Western thinking?

AA: We have now veered into the philosophy of religion. I think that the categories of omnipotence and omniscience applied to God in classical Western metaphysics run into all sorts of troubles, as the controversies in Western philosophy of religion easily reveal. Africans conceive God as at once remote and near, transcendental and immanent. I thought the categories of power and glory can best capture this African perspective, especially against the background of the conception of a universe which is incomplete but is seemingly striving towards completeness, which again is impossible. In the end, however, consolation philosophy is a frankly individual system of thought. Many Africans may have reasons to disagree with my submissions.

3:AM: Consolation itself is something that has roots in various philosophical traditions – Existentialism, Pragmatism, Buddhism, Catholicism, Taoism, Stoicism, Epicureanism – and philosophers such as Kant, St Augustine, Boethius and so on have all used it in some way. How does your use of the term converge with these traditions and where does it diverge – I guess my question is what are the features of consolation as you use it that makes it specifically African?

AA: Thankfully, I anticipated this question and answered it earlier, briefly though. The point of convergence is where we all agree that the aspirations of the human mind and human endeavours in general, constitute projects aimed at finding meaning in a life where we often encounter meaninglessness. For instance, when we appeal to God in moments of our helplessness we are answered with the silence of the world. However, I went further than the philosophers and currents you identified in that I constructed an entire philosophical system on the foundation provided by the term ‘consolation’. The doctrine of mood, the analysis of human emotions, my philosophical psychology, the concept of the melancholy being, etc. all find there bearing in direct relation to the term ‘consolation’.

3:AM: Why do you say your work isn’t a work of existentialism but rather African rationalism? This may strike a western reader as being a strange claim given that you emphasise a certain emotionalism at the heart of the thinking, where what you are thinking about is what you call ‘the phenomenon of the melancholy being.’ Who is this melancholy being and why do you call your work rationalistic?

AA: Well, I miay be guilty of exuberance here. Nevertheless, I wanted to avoid being seen as a Western existentialist. I am quite particular about this ‘originality’ stuff. My work, perhaps, is a kind of African existentialism. I prefer the term ‘consolationism’. I do not think emphasising feelings makes a work automatically existentialist, unless you are saying that we can only have a scientific philosophy, which effectively makes philosophy a handmaid of the sciences, just as philosophy was the handmaid of religion in the medieval age. I borrow from the sciences where necessary, but I am not carried away by scientism. There is a whole lot of experience that science cannot adequately encompass. My work is rationalistic because it relies on reason rather than religion or received African traditional knowledge. I believe my system is comprehensive and plausible, providing us with a different metaphysical perspective of reality.

The melancholy being is the techno-emotive being, the human being living in a highly technological world who ensures that technology serves human emotional interests in politics, religion, the ideological arena, entertainment, health, education, sports, military affairs, etc. The melancholy man is you and I, and any entity anywhere in the universe capable of conscious thinking. The melancholy being pursues intellectual goals from an emotional locus.

3:AM: Why do you find panpsychism an important part of your consolation philosophy?

AA: Panpsychism plays a metaphysical and epistemological role in my thought-system. Metaphysically, panpsychism justifies the idealistic submission that mind (as mood) is prior to matter. Epistemologically, panpsychism makes knowledge of the self and the external world possible. If knowing involves experience or, to use Galen Strawson’s term, experiential being, then we are able to represent things and penetrate them only because mind is already diffused in all things, at various levels of sophistication, micro and macro. Panpsychism is rooted in the African life-world. It is fitting that an African philosopher should take up the matter in this century. I have just commenced my intellectual work and hope to further develop my panpsychist ideas. Western philosophers from Thales to William Seager have either flirted with panpsychism or have taken it seriously. In one dimension, panpsychism may appear unbelievable, but, then, is the appearance of the universe any less incredulous?

3:AM: As you point out, Augustine, Origen and others were of African origin. Do you think everything they wrote was influenced by Western inspiration or can we detect African thinking also in their work that until now has perhaps been neglected perhaps because its only now that we are getting clear what an African philosophical tradition might look like?

AA: This is a tricky question. Firstly, I think the only characteristic uniquely African in relation to the Western life-world is our tendency to see things contextually, complementarily, holistically. The African is closer to the quantum mechanist than the classical physicist. Now, do the works of St Augustine and Origin reveal this tendency? I am more familiar with St Augustine than Origen. I am reluctant to say there was something specifically African in St Augustine’s thought. He appears to me a thoroughly Western thinker.

African Consolation philosophy is a metaphysical system aligned with the African life world. So how does it construct a monistic system set to reconstruct a theoretical universe that is both different from the western model and yet remaining in solidarity with it?

AA: Monism asserts that there is one fundamental stuff in the universe which can be matter or mind or even a combination of both. Consolation philosophy posits the primacy of mood in the universe. Since I conceive mood as a proto-mind, my thought-system is an African idealism. It is monistic because it reduces everything in the universe to mood, a creative principle driven by an all-pervading logic that is nothing more than yearning. This assertion has implication for determinism and freedom. Rigid determinism and freedom are denied, with the notion of fatalism taking precedence. Fatalism allows for possibilities and novelties within the boundary of yearning which conditions everything in existence. My construction of a coherent philosophy around the themes of determinism, freedom, teleology, and my reflection on the intellect-emotion relation are so original that they cannot fit smoothly in the Western conceptual scheme. But since these themes feature prominently in Western philosophy, there is clearly a thematic relation between consolationism as African philosophy and Western philosophy. Richard, as you must have noticed, I went to great lengths to show in Existence and Consolation that my basic inspiration came from Africa rather than from the West.

3:AM: What role does a kind of Nietzschean amor fati play in this system?

AA: Amor fati is a kind of ethical resignation to the universal sway of fatalism, the necessary occurrence of events which are not rigidly conditioned beforehand but which become rigidly determined after their occurrence. However, amor fati is not Eastern resignation. Amor fati is a call to action by those fully aware that failure mocks the best human effort, ultimately.

3:AM: Can you say how consolation philosophy’s response to what you call the ‘mechanism-teleology opposition’ – which I take it is the problem of finding meaning in what seems to be a meaning-free physics - is captured by the idea of ‘yearning’? Is there a link here between this idea of constant yearning and ideas found in eastern philosophy?

AA: I tried to transgress the mechanism-teleology border in my book with the concept of yearning. If yearning is a distinguishing feature of mood and mood is primal, it stands to reason that the notion of chance cannot escape this ubiquitous yearning comprehended as the logic of existence. Chance, then, resolves into purpose and mechanism becomes another term for teleology. What remains for humans, and any other thinking entity in the universe, is to know what the ultimate purpose of existence is. Can we achieve this supreme knowledge? Very, very unlikely. Thus the yearning continues. As we yearn, emotionally and intellectually, we create semblances of meaning without reaching full meaning. These semblances are yet adequate for the purpose of living. This is our consolation. This is the point my book is making. There is a link between this idea of yearning and the notion of tanha in Buddhism. The yearning, the desire, is eternal. It births mechanism and purpose. Should a nirvana be achieved, whatever existential or intellectual bliss is expected will be the starting point of another stage of tanha.

3:AM: How does this system end in consolation if yearning is never fulfilled, evil is always with us, freedom is but an illusion, and how do you ground this outside just human subjectivity? Why isn’t this just an anthropomorphising of the universe?

AA: You have just admitted that consolation philosophy is a pessimistic system at bottom. I agree with you. For the external universe (which I conceive to be ‘minded’), the consolation for its non-perfection is the very fact that it emerged at all as incompleteness seeking an impossible completeness. For humans the consolation lies in the moment-to-moment maximisation of the emotion of joy which give bearing to human intellectual projects.

About grounding this perspective outside human subjectivity, Richard, this is another way of saying that panpsychism is unbelievable or false outright. The doctrine of mood does the grounding. The human mind is a mirror of external reality in that yearning characterises both phenomena, making them merely aspects of the same fundamental reality which I call mood. I confess that I do have my moments of doubt. The consolationist system is speculative philosophy, after all. If we reject the panpsychist framework of consolation philosophy, it seems to me that the external world becomes completely impenetrable, not just partially impenetrable as things stand now. Scientists believe that physics comprehends just 5% of reality. This 5% is ordinary matter which physics studies. The rest is uncharted universes. If we reject my mind-matter reconciliation project, then even the little we know about reality is mere anthropomorphism. All the so-called inviolable laws of nature will then be seen as mere idealisations localised in the human brain. Are you ready to accept this conclusion?

3:AM: And how does this 21st century African synthesis stand in relation to Western and Oriental philosophies?

AA: Thematic preoccupations sustain the solidarity between the African synthesis and the Western and Oriental traditions. Like Western and Oriental philosophies, consolation philosophy seeks to produce a certain picture of the universe, the main difference being that consolationism insists its perspective of the universe is an African perspective which, nevertheless, is universalisable. The universalisation of the doctrine of mood, for instance, can enliven the debate on panpsychism at the intercultural or comparative level. I am currently comparing my ideas on panpsychism with the panpsychist views of Western analytical philosophers like Galen Strawson, David Chalmers, T.L. Sprigge, William Seager, on the one hand, and forms of panpsychism in the Vedanta Advaita school of Hinduism on the other hand. The 21st century African synthesis stands in a relation of a universalised particular calling on the Western and Oriental traditions for a more inclusive global philosophy. As a representative of African philosophy, the African synthesis seeks a place at the roundtable of world philosophy.

3:AM: And for the readers here at 3:AM, are there five books we should be reading to get us further into your philosophical world?

AA: Well, Richard, I don’t know if the books are up to five, but there certainly are a number of books which may shed light on the consolationist synthesis. There is Atuolu Omalu: Some Unanswered Questions in Contemporary African Philosophy edited by my friend Jonathan Chimakonam and published by University Press of America in which I have a significant chapter. There is also Ka Osi So Onye: African Philosophy in the Postmodern Era (Vernon Press, 2015), in which I also have a chapter titled “Consolationism: A Postmodern Exposition.” There is African Philosophy and Environmental Conservation edited by Chimakonam and published by Routledge, in which I have a chapter. I’m currently trying to secure a major funding for my next book. This book will clarify the more problematic issues raised in my first book, some of which you have insightfully identified. I intend to make my thought more precise in my next book, more analytical. Existence and Consolation is a young man’s book and has a number of flaws. I produced the first draft in my late twenties. My thinking on consolationism continues to mature. I hope to restate consolation philosophy better in my next book.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshallis still biding his time.

Buy his new book hereor his first book hereto keep him biding!