Ernest Gellner and Issues of Enchanted Modernities

Interview by Richard Marshall

'He came in one day, didn’t have any notes, and said, “Today, I’m going to talk about Evolutionism, Functionalism, Structural-Functionalism, Structuralism and Marxism, and their relationships. And there was a rustling in the front row and a young voice said, “Sorry, Dr Gellner, that’s tomorrow. Today, you’re giving the third lecture on Islam and Politics.” And Ernest looked and said, “Just give me a moment.” He turned away and a minute later, turned round and gave a perfect third lecture on Islam and Politics. So that’s how Ernest was.'

'I’ve never experienced any spiritual presence of any kind. So my attitude towards it is exactly my attitude towards God, which is based, I think, on Russell, who when he was asked what the greatest invention of the twentieth century was, said: “the suspended judgment”. It wasn’t the twentieth century, it was earlier, but it was one of the great inventions. But the point really is that science, as any good scientist knows, is not about knowing something as certain. It’s positing a hypothesis which is true until it’s proven false. So you suspend judgment on its ultimate truth. And the same is true of my attitude to the world.'

'If you had the invidious task of choosing bad empires and less bad empires, I would put the British as a less bad empire. And that’s for the reason I’ve mentioned; that is, it’s not an ideological empire. It’s an economic empire. Economic predation has a devastating effect. And in order to maintain the peace there were famous examples of atrocity - Amritsar is the most famous, also the crushing of the Mau Mau. Although you have these massacres, when you look at Amritsar and when you look at the size of the British Empire, over 300 years, and you think that the worst example you can get is two thousand casualties (and even so there’s a complicated story of what happened), it’s not a record like the Belgian Congo’s. It’s not a record like the Portuguese and the Spanish in South America. It’s not a record even like the French in Southeast Asia and (certainly) Algeria. In other words, it’s shocking to us, especially when you combine it with slavery and the slave trade. And yet, because it was a rational, economic matter, and there were reasons for providing peace, providing a reasonable legal system, perhaps trying to improve the communications systems, there were some features that meant that even Indians, after Independence, thought, “Well, we got some good things out of it”..'

'Max Weber had said, China is a magic garden. He understood China better than most, though his The Religion of China, is much criticised. But it’s a wonderful book and he understood the basic thing, which is that it’s different from us and it’s a magical world. We now have China, Japan, South America, Continental Europe, India, the Pacific cultures, on one side; and we have the Anglosphere on the other. So which is right? Is it the magical world or us?'

Alan Macfarlane taught at theDepartment of Social Anthropology Cambridge University for thirty-four years and is now Emeritus Professor of Anthropological Science and a Life Fellow of King's College, Cambridge. As an anthropologist and historian he has worked on England, Nepal, Japan and China. He has focused on a comparative study of the origins and nature of the modern world. This is an extract from a new series 'Alan Macfarlane and Enchanted Modernity' starting later this year at 3:16 where I interview him about a wide range of topics. These extracts from the series can be seen on youtube here and here.

As a 'taster' to the full range of the interviews, he here discusses his relationship and assessment of his friend the philosopher and anthropologist/sociologist Ernest Gellner, Weber's disenchantment thesis and its relationship to science and modernity, Joseph Needham's puzzle, ghosts, Kuhn's pending tray, anthropology's relationship with Empire and Colonialism, his assessment of the British Empire, why anthropologist's stopped collecting relics, how Nepal and Japan expanded his understanding of religion, the discovery that Japan and China are different but enchanted modern states, and why Jack Goody was wrong to think there's no fundamental difference between western and far eastern civilisations.

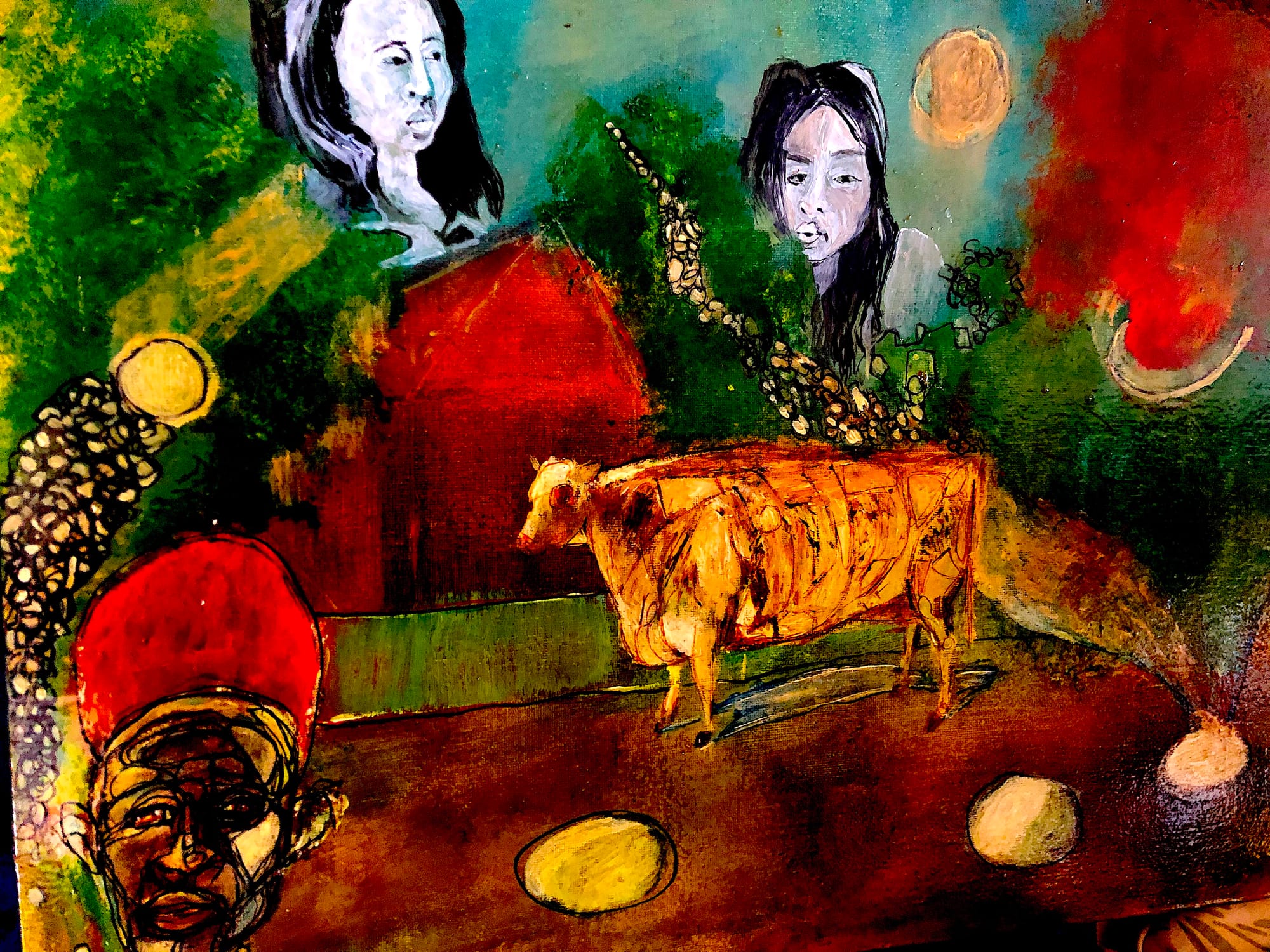

3:16: Perhaps it’s a good time to talk about Gellner. He’s probably the latest or last manifestation of Weberian thinking. He’s obviously very interested in enchantment, disenchantment, how we became modern. And then we can talk about how you came in and looked at this. I was reading about how you told him about Japan and how the Japanese believed in spirits; and he thought they were just trying to fool you. He very much came out of a European context. He was Czech and the Cold War was the deep background to a lot of thinking. He was trying to answer the question of how the miracle happened. He emphasised the accidental coming together of different aspects; it wasn’t Western triumphalism. But he did come across as asserting that there was something exceptional. Your work is an interesting counterpoint or even corrective to this. Can you outline what the Gellner position was, and where you come into it, and where we should be now with it?

Alan Macfarlane: A pleasure, because Ernest was one of the two or three most influential living thinkers on my work. Like Jack Goody he was head of my department and a friend with whom I would stay. I first met him at the LSE in 1967. He was different, as you’ve just described, as a teacher. He took ordinary people seriously. I once asked him why he was so nice to me and he said, in typical Ernest fashion: “In The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, at the beginning of term, the headmistress says to the teachers: “Now, ladies, you’re going to be teaching a lot of these young girls, and a lot of them will be very horrible and unpleasant. But be sure to be nice to our young ladies; you never know who they might marry””. Ernest said, “That’s my philosophy. Be nice to people. You never know whether a humble person you meet in the street may turn out to be a multimillionaire or someone who’s going to be important in your life. Be nice to them.” Of course, this is the secret of Cambridge and Oxford Universities. We were nice to our students because, twenty or thirty years later, they might be Prime Minister or head of the Sainsbury Foundation. It’s wise to be nice to them.

That wasn’t the reason he was nice; but he was nice. With me, he would stop and after we had met once or twice and we’d talked, he would stop and stay “Hello, Alan, how are you?” That a very senior person like that actually remembered my name!

And then I read an article of his, called “Concepts and Society”, which was like a bombshell. It was the Humean idea that minds are like a set of receptors to the outside world; we don’t see the world directly, and the receptors change over time and in different societies. So what we “see” is determined by something other than our vision, and different societies will “see” differently. Now that was a way of thinking I'd never had before. And though I may have gone to lectures, I certainly went to seminars where he was present.

When I went to Nepal, even by then, we had obviously formed a friendship and I was in touch with him. He was interested in Nepal; and when I came back to Cambridge, and went to King’s, we renewed our friendship. He sent his son David (who is a distinguished anthropologist) to meet me when he was 16 or 17 and talk about whether he should do anthropology. Ernest read my book on Nepal, in proofs in the field, and wrote a wonderful article for the front page of the Times Literary Supplement. Later, he was very supportive about my work.

What I loved about Ernest, apart from this deep interest in other people (though he was shy and not very communicative) was that he combined disciplines. He was a sociologist; was trained as a philosopher; and had a PhD in anthropology. So he crossed disciplines, as I was trying to do.

He was a wonderful lecturer. My metaphor for him is a cement mixer. He had these few ideas churning and churning in his mind and then they would be dumped out. One lovely proof of the fact that he had a whole library in his mind of books and ideas (I can’t remember whether I witnessed it or someone told me about it) was an occasion when he came to Cambridge as a lecturer, and he gave several courses. He gave an eight-lecture course on Islam and Politics and gave an eight-lecture course on great social theories.

He came in one day, didn’t have any notes, and said, “Today, I’m going to talk about Evolutionism, Functionalism, Structural-Functionalism, Structuralism and Marxism, and their relationships. And there was a rustling in the front row and a young voice said, “Sorry, Dr Gellner, that’s tomorrow. Today, you’re giving the third lecture on Islam and Politics.” And Ernest looked and said, “Just give me a moment.” He turned away and a minute later, turned round and gave a perfect third lecture on Islam and Politics. So that’s how Ernest was.

Now, the other thing I liked about him was that he knew what the question was. Anyone can give an answer if he knows what the right question is. As Einstein pointed out, it’s finding the questions. And Ernest, because of his Czech background, because of his wide reading and knowledge of Communist thought, Islam, Western philosophy, Hume and so on, knew how to frame the question. The question is: “Why has the miracle occurred?” As you say, he didn't think it was inevitable and he was constantly puzzled by it. But it has happened, against all the chances, all the odds.

Again and again, we might have had the emergence of a modern civilisation of separations We might have had it in Florence; we might have had it in Venice; we might have had it in Islam; we might have had it, as Jack Goody points out, in Hangzhou or Fuzhou or the Southern Song, etc.

But it didn’t. It was stopped; it was crushed; it was ended. But, in the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth century, in one part of the world, it emerged. Why, why, why? He was constantly asking this question; and, for example, saw The Plough and the Book as an attempt to answer it. He couldn’t buy the Marxist story, he was very critical of it. Anthropology doesn’t give you answers to this question directly. He hadn’t found any historians. He was interested in my work and that at least I was asking the question, even though he wasn’t satisfied with my answer.

Again, I was deeply influenced. But again, since he’s died and I look again at his work, I can see that, like Jack Goody, he hasn’t had the advantage I’ve had of moving out of monotheistic Western civilisations. Jack did, of course, with work in Africa; and so he constantly did accept there was a difference between Africa and Eurasia. Because he knew it, he'd been there. But he didn’t know it about Asia; and nor did Ernest. Ernest was trapped within Western monotheism – which includes Marxism, which is another Western monotheism; and Islam; and so on. This means that India and China and Japan were disturbing for him because he was a very rational, clear, Western thinker.

The mess, the dualism, the quantum thinking, the binary illogicality. Something like Buddhism would be an anathema. Ernest was to me what Einstein was to physicists. He’d solved many problems through a rational, Newtonian, binary, logical system of thought derived from the Greeks. This was Ernest through and through. But when Einstein was faced with quantum theory, and God playing dice, he was deeply troubled, as we know. He was committed to God not playing dice. He could not accept quantum theory. It undermined the basic premises of Western physics. And for Ernest, Eastern thought did the same.

The story that you mentioned illustrates it in an Ernest–ish way. He asked: “Alan, tell me something about Japan.” I asked why, and he said, “Well, I’ve been asked to give a lecture in Osaka.” I said: “Good, I’m glad you're going there. What on?” He said, “Town planning.” I said, “Oh, that’s a concealed part of your intellectual biography I didn’t know about.” He said, “No, I know nothing about town planning, I have no interest in it, but they’re paying me a lot of money, so I’m going.”

So I told him a few things about Japan and he was close friends with Ronald Dore, who told him other things.

He came back and I asked how he got on. He was very like Peter Laslett when he went to Japan; and he’d come back and said the same as many people here. He said, “Oh what a wonderful place. Wonderful food, wonderful gardens, wonderful this and that”. But Ernest said, “Oh, it’s awful. The food was great and they were as kind as could be, and very efficient; but philosophically, what a shambles. You couldn’t talk to them.” He didn’t listen and he didn't understand them.

He said, “I’ll give you an example. There I was in this very smart hotel, and in these hotels you put the shoes outside the door to be polished for the morning. And I put them outside and a Japanese gentleman came along and looked at them and I said “Shoes. Please clean for morning.” He bowed and said “Hai, hai”. But when I went back next morning they were as dirty as they had been the day before.” He hadn’t listened. And this happened, he said, in many different situations. He just didn’t seem to understand.

He said, “Alan, how can you have the richest, strongest economy and most sophisticated technology in the world run on a linguistic system where you can't talk to people?'' He said, “Well, I have a theory, which is that if you go to the headquarters of Toshiba or the other great industrial firms, and up to the boardroom at the top, there is a sign on the door that says that when you go through this door you can talk in logical, sensible ways. You open the door and then they become like us.” It’s obviously nonsense.

So I think if he’d been younger and had that experience, he would have adapted. But at that point in his life, like many Westerners, he lacked that leap of imagination into an entirely different world. He’d done it a bit with fieldwork in Morocco. He worked in the Atlas and the Saints there, who are partly magical. So he’d taken some steps down the road. But to get inside the logical system of an entirely ancient philosophy, with that level of difference – he didn’t have a chance to do it in his lifetime.

3:16: Part of Gellner’s understanding about why you had to be disenchanted in order for industrialisation to take place was a kind of functional explanation. If you thought there were spirits in the river you couldn’t investigate it as a scientist. Now, you’re saying that isn't the way people in China and Japan look at things. They treat rivers as spirits and also as scientific objects. How do you explain that then? I suppose that would be Gellner’s puzzle. If you’re right, the question then becomes: what’s happening to shamanism when they’re doing technology?

AM: That’s a question I often ask myself and I haven’t quite thought it out. I hope you and your viewers know of the Needham Question. Joseph Needham was a biochemist and wrote a great study, Science and Civilization in China. And the Needham Question was similar: why was it that science developed in the West and not in China? They had all the technology until about 1400 and yet China never developed experimental science. Why not?

Needham never solved the problem at all, but he has a number of theories. One of them is the instability of China’s philosophical system. If you have a world that is not separated off, where everything is alive, then you can’t have experimental science. For instance, life in Buddhist thought is filled with maya. The same is in Daoism and so on. Therefore it would constantly be changing. Yin/yang is a cosmology of constant shifts. Yin into yang and yang into yin. It’s a quantum world where everything is both/and, where you cannot have the sound of one hand clapping.

And the basis of experimental science is repeatability. If you do an experiment in the West you have the same conditions, you should have the same outcome and that proves the experiment is true. But in China you can't assume that because things will have changed. Therefore you can’t have experimental science. You can have observational science, where things seem to be associated. Chinese medicine is based on observed patterns in the past. But you can’t test the links – why something causes or can cure lots of diseases. You can't test it, you can’t do experiments.

So part of Needham's solution is that the West had, through its Greek science and its Christian principles and attitudes to nature, a belief in laws and repeatability and uniformity. And in China, in Eastern systems, you don't have that. You could get around this problem by saying that you couldn’t have a Scientific Revolution in China, just as you couldn't have an Industrial Revolution in China, because their economy had gone down the path of what my friend Hayami calls an “Industrious Revolution”. They had increased their production by working harder and having a bigger population. In England we had gone through an Industrial Revolution, where we replaced labour by machinery. In China their path could never lead to an Industrial Revolution; our path could, and did, lead to it.

So the Industrial Revolution could never have happened in Japan or in China; but once it’s happened, it’s there on a shelf. It’s like you and I – neither of us could invent a Windows operating system, but once it’s there we use it without knowing anything about computers to do it. So once there is science, once there is Western technology, once there is an industrial civilisation, you buy it off the peg.

It’s better than that, because once you’ve got it off the peg you reverse engineer it, you understand how it works and you have new inventions. And so the Chinese and the Japanese are quite capable of absorbing it, using science, developing it; but the original formulation of it would not and could not have happened there. We had to invent it. But once it was invented it was for mankind. That’s probably the solution.

3:16: Do you think Gellner would have been able to accommodate the idea of combining disenchantment and modernity, had he gone on within the same framework, or would it have broken the framework?

AM: Well, I don’t think the idea I’ve just developed would have been too difficult for him. It’s quite a simple idea, that the inventor of a system and the users of the system are different. It also applies to mathematics. As you said, there are differences between schools of anthropology, within departments even, throughout the world; but mathematicians and physicists all talk the same language. I remember my friend, Gerry Martin, saying that this was what puzzled him about anthropology. It was culture-bound. Because he’s an engineer. He could meet a Japanese or Chinese engineer and within ten seconds they were talking the same language. The language of engineering is universal. The language of mathematics is universal.

And yet Japanese and Chinese have different mathematical systems, that are pretty powerful and pretty good; and many people feel that early on in China, they had gone a long way towards Euclidean mathematics. They solved many Western mathematical problems using their system, which is founded on different principles and uses different operations. But I think in mathematics they can probably do both. A good traditional Chinese mathematician can use Western mathematics and solve problems, but they use the abacus rather than the calculator. And the abacus is better than the calculator for certain things.

And the same with traditional medicine. I have a wonderful Chinese friend who is a nun and is also a trained Western doctor with medical qualifications. She also has a PhD in French as well as being the head of a Buddhist nunnery. Her hobby is reading mathematics. She had a pile of books beside her and she read at night. What are they? Oh, that’s Euclid’s Elements,that’s Newton’s Principia (the most difficult book in the world), here’s the Universal Encyclopedia of Mathematics...That’s what she read as bedtime reading. But she’s also one of the leading Chinese traditional medicine practitioners. In other words she knows about herbal remedies, acupuncture, all these things. She knows how to use them. If she needs Western medicine she uses that. So she is the world into which we’re developing. There are certain problems for which acupuncture works.

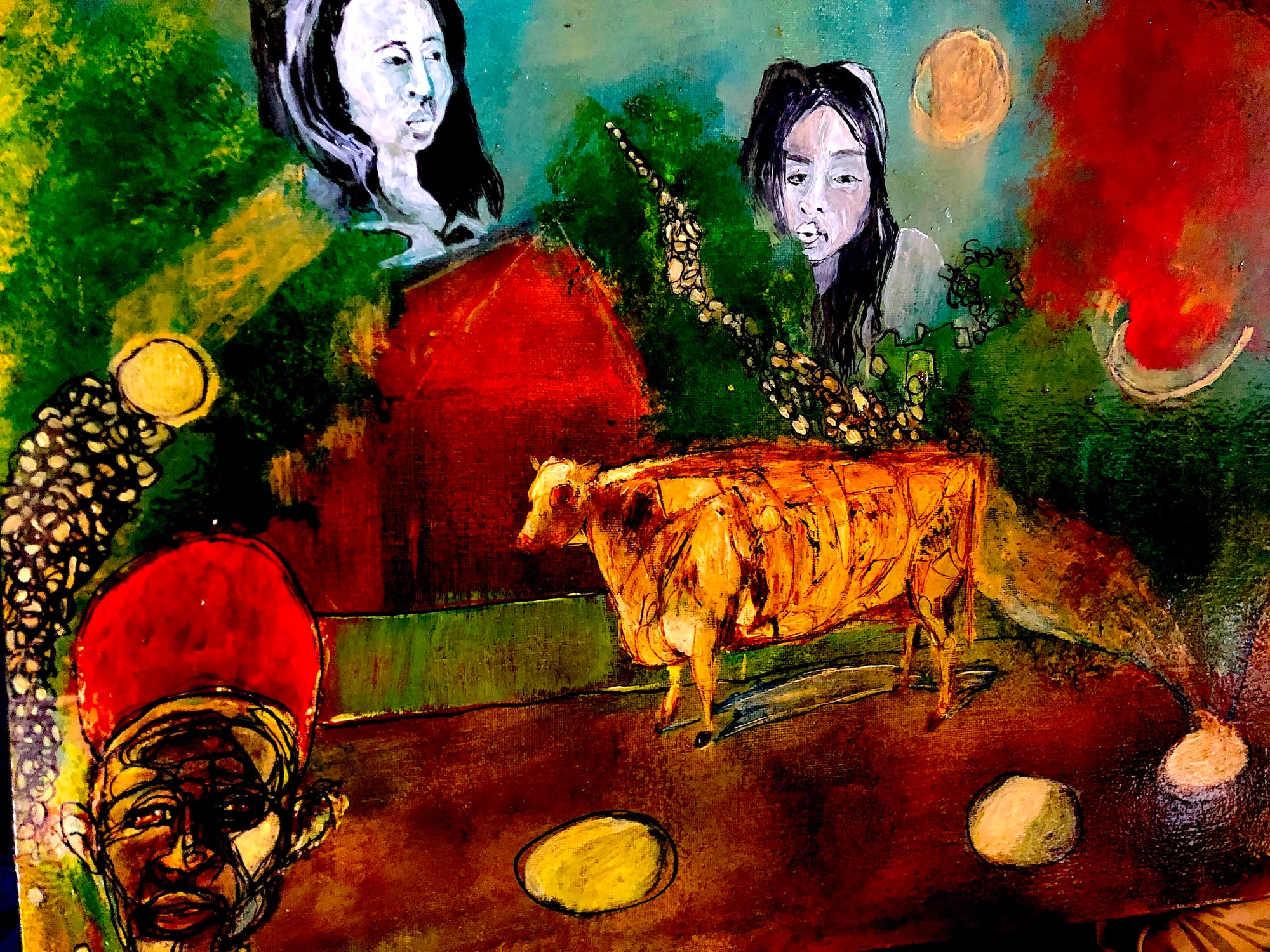

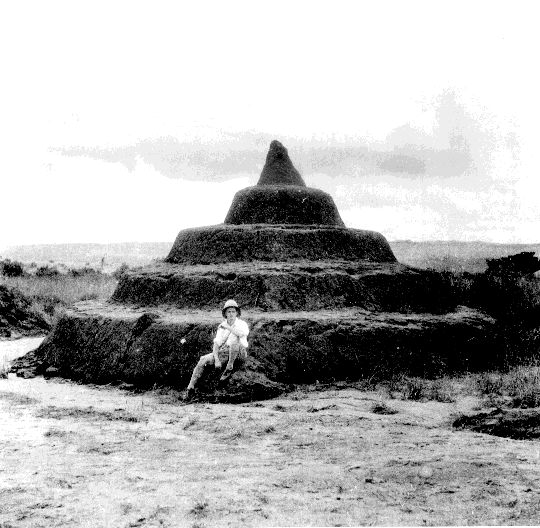

[Pic: Gurung shamans and the spirits they see in their trance.

The event occurred on 11th January 1993.

In Piers Vitebski, The Shaman (2001), pp. 20-1, where the photograph is reproduced, it is described as follows. ‘When one of the shamans saw the photograph he exclaimed, “This is exactly what the god, the witches and the ancestors look like! … These are the exact colours I see, in exactly the right positions. But how can a camera see what only I can see?” The shaman explained that the yellow line running right across the picture is what the ancestor spirits who come to protected the shamans look like as they arrive. The orange bar across the shamans’ heads is the god Khhlye Sondi Phhresondi who has come to protect them from the souls of witches. These witches, who are actually malevolent living humans, can be seen above the heads of three of the shamans in the form of green wavy lines. The witches are absent at two significant points. These are absent at two significant points. These are where the protective orange line is at its strongest, and over the head of one shaman on the right who dropped out for a rest and is therefore not engaged in the spiritual battle. The photograph is published here for the first time, with the permission of the shamans.’

The shaman who gave his reaction is my friend Yarjung Kromje Tamu and the photograph is produced courtesy of Fergus Bowes-Lyon.]

3:16: One of the fascinating things when I was reading your account in Nepal was that you’ve actually got on the front cover of your book spirits or ghosts. I’m sitting there, thinking, “Wait a minute, what’s going on here? Am I now in an episode of The Ring or one of these Japanese ghost horror stories? Is Alan saying there are ghosts and that this is real?” And the same with your interest in traditional medicine, because that’s obviously quite controversial. A lot of people think of it in terms of quackery. But clearly you’ve got a lot of respect for it; and so do a vast number of people. Personally, have you now come to accept the rather strange metaphysical claims of these religions, that there are these spirits, beyond just saying that this is what people believe?

AM: There are several interesting questions there. The first is the simpler, which is the medical traditions of India and China. I really can’t understand, apart from professionals wanting to monopolise the market, why there is so much resistance among traditional Western doctors and others to Eastern medicines. One can understand why they want to hog the market. But I’ve tried these things and they work. As an example, I was working in a remote part of China with one of my students and someone slammed a van door on my finger. It was swelling and blackening up. And she rushed off to a shop and got some traditional medicine, an ointment, and put it on. Within about ten minutes the swelling was going down and the black was going. Now, I have it in my cupboard here and I’ve given it to myself when I’ve banged myself, and I’ve given it to others, and it works. I’ve got what they call dog skins – I don’t think they are dog skins – but if you have a pain in your back you put one of them on and the pain goes. I have cold medicine which is much better than any Western cold medicine. Tea, ginseng…Tea is the most important..

So, they work very well for certain things, though not everything. Why anyone would be so stupid as to throw away five thousand years of human knowledge and half the world’s population just because we had a (pretty pathetic) medical history until the later nineteenth century when we could see what we were doing.

Now the spirits. Everyone usually comes out with Shakespeare: "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy". Basically, one of the reasons I stopped being a Christian was that I never felt Christ come into my heart. I never had the experience of an inner presence, which is what I was promised. And I’ve never experienced any spiritual presence of any kind. So my attitude towards it is exactly my attitude towards God, which is based, I think, on Russell, who when he was asked what the greatest invention of the twentieth century was, said: “the suspended judgment”. It wasn’t the twentieth century, it was earlier, but it was one of the great inventions. But the point really is that science, as any good scientist knows, is not about knowing something as certain. It’s positing a hypothesis which is true until it’s proven false. So you suspend judgment on its ultimate truth. And the same is true of my attitude to the world. I don’t know that God exists, I don’t know He doesn’t exist, it’s a suspended judgment.

And so it’s the same when I encounter examples of spirits. I’ll just give you one or two cases. Kuhn suggests, that paradigms exist and then discrepancies, anomalies, exceptions emerge. They accumulate to such a weight that finally the paradigms are toppled. Now, if that’s how you change a paradigm then what you should do is, instead of brushing it aside, you should put them in a box or a “Suspended” Pending Tray. You put it there. You don’t understand the answer; you suspend the judgment. Another one comes along, you put it in; and then a pattern may emerge in the tray.

So, a few things in my Pending Tray...We’ll start with Sarah (my wife and felow researcher) and the spirits. In the village in Nepal it’s believed that when a person dies they don’t go immediately to the village of the dead (Plah Nasa)they linger around and then they have to be taken along the path to the village of the dead through a ritual. So they're hovering there and they’re a bit dangerous at that point if they’ve had an unpleasant death or if their descendants don’t remember them. They can cause trouble. Anyway, there was a close friend of ours, a man with whom we’d stayed on our first two visits, and my classificatory uncle (I called him “Uncle”, Ateba). I was fond of him and he lived in a house thirty yards above ours. He was elderly and one day he died. Normally the body would be taken down to the river straight away and burnt there; and that would partly cool the presence of the spirit. But there was terrible monsoon rain, and it’s an almost sheer cliff that you have to go down, so it was very dangerous. So they didn’t go down and left him in the house.

That night, Sarah woke me in the house about three in the morning, tapped me and said,

“Alan, can you see those faces up there?”

We’d had a little house built and about six feet above our heads was a bamboo frame and mat as the ceiling. It wasn’t far above us and we were lying, looking up at it. I said,

“No, I can’t see any faces.”

She said, “Well, they look like elderly women. But they look strange because their mouths have fallen in and they don’t have teeth. They look as if they’re dead. There are three or four of them and they’re looking down on me like a set of mirrors in a disco, at different angles.

”I said, “Are you sure you can see them?”

“Yes!”

“Are you sure you’re awake?”

“Yes, I’m awake.”

I tapped her a few times and I said, “Let’s talk about something else” and we did. She was clearly awake.

I asked, “Can you still see them?”

“Yes!”

So I went to the windows and opened the blinds. It was still pretty dark and I looked at my watch, came back and tapped her.

“Are they still there?”

“Yes!”

This went on for an hour or two, then dawn came through the curtains and the cockerel crowed.

And she said, “They’re going!” and they faded away.

Now that happened to her once; and once or twice afterwards she said she felt they were wanting to come, but she didn’t want to see them and she pushed them away.

The sequel to this is that we went up to the house above where my closest Gurung friend, my adopted sister, lived. I was very, very close to Dilmaya and over breakfast she asked us how we’d been. We said “Fine, but we’ve had this strange experience.” We expected her to be shocked when Sarah described what she’d seen, but Dilmaya said, “Oh yes, they were the spirits of Ateba’s dead wives” (he’d been married several times). They’d come down to fetch him. That was to be expected.

So that was the first Gurung experience. The second was at Dilmaya’s three-day funeral (she died tragically young). At one point they had a ritual where she’s being taken off to the land of the dead and they bring in a sheep, which has her spirit inside. So they fed her with food and brushed her with her comb, then showed herself in her mirror. And I filmed all this. I was her classificatory brother so I had to do these things with Sarah. The sheep has a spirit inside her; and another sheep, who is her friend, also has a spirit. The sheep will eat the food; and then they sacrifice the sheep and examine its insides. They believe that the spirit having eaten the food there will be no remains of it. It consisted of biscuits, orange peel and some durable things such as cigarette wrapping. But there won’t be any trace of them. While I was filming with one camera I sent my MPhil student Tek to go off and watch them doing this and take photographs. He said, “Yes, there’s nothing there.” So within half an hour it had all disappeared.

The third example was the photograph. I was Acting Head in my department at the time. On the first day I was busy setting up things and a young man who was an undergraduate at Newcastle University, came and said, “Dr Macfarlane, I’ve been to the village next to yours, and I went to a ritual there, run by some shamans. I took some photographs and there’s something puzzling about them. Can I show you?” I said, “Fine”, and he projected them. Photograph Number Twenty showed a row of four shamans doing a very, powerful ritual on behalf of a dead spirit who was refusing to go and was being attacked by witches. To fight away the witches the shaman has to go into trance and beat his drums. There’s then an almighty battle in which the shaman may be killed, between the witches and the protective ancestors and the protective god of the shamans. In trance the shaman, who is a close friend of mine and who is now in England (Yarjung Kromje Pochu) fought these demons.

Photograph Twenty-One is the one on the cover of the book, where you see these lights flashing down – yellow lights, green lights and a rainbow. Photograph Twenty-Two, taken just a second later, is normal. As this was being shown, by some strange chance, in walked Yarjung, the shaman in the picture. He looked at it and said, “That’s me, that’s my spirits. The camera has got exactly what I see in my mind’s eye when I’m in trance.” I asked, “How can a camera capture spirits like that?” He said, “I don’t know, but that’s what I see.” I sent it back to Kodak and they said: “Sometimes we get sunspots, sometimes the lens freezes, you get odd effects and so on.” I showed it to an expert on paranormal psychology, Nick Humphrey, and he said, “Well, you do get these things, but the chances of that happening at that moment is millions to one. It’s highly improbable.”

The same thing happened again. The same shaman came to Cambridge and he offered to give some of his precious objects to the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The most precious was his father’s drum. He had to sleep with it in a certain position for a week before the handing-over ceremony. He handed it over in the hub of the Museum, in one of the rooms there; and as he handed it over in the presence of the MPhil students and some of the curators, all of the lights throughout the Museum fused and there was darkness. When they examined the circuits they found that a huge electrical surge had struck, in that room, the light above, and had fused all the lights in the Museum.

And then Sarah had another experience and I’ll finish with that one. We had a student, who’s sadly died recently, Vinay Srivastava, who was doing his doctorate in India on camel-herders in Rajasthan, who have shamans. He took photographs over there and came back. Sarah at that time was the only person in the department who knew how to use our darkroom and develop photographs. So Vinay asked Sarah for help in developing the photographs and while they were doing this, Vinay said, “The odd thing about this is that when I was photographing a group of people there was a powerful shaman among them and when I asked him, “Can I photograph you?” he said “Yes, that’s fine but it won’t come out on the photograph. It will be a blank.”” They developed the photographs together and as the picture came into view, there were all the other people but a blank where he had been.

I’ve gathered a few other examples from other anthropologists who’ve had similar experiences. An Indian friend and publisher has asked “Why don’t you make a good ‘Anthropologist’s Spook Book?” So who knows? But what I do is I put them in the Pending Tray. They're not enough in themselves for me to throw away entirely Western philosophy and science. But if you think about it for a second, if you had been here three hundred years ago and someone had said, “You will soon be sending pictures and sounds through the air and you’re going to send huge forces that will drive everything around you through wires” – then before electricity, the Internet, before Bluetooth, it would have been incredible. So if we accept multiverses in modern physics, what’s to stop us saying, “Who knows if there are a number of parallel realities within which all these spirits and things could make sense?”

3:16: One thing I want to ask about is anthropology as a practice and its link with the Empire. Anthropologists and anthropology in its golden age was intimately linked with it. So how do you see the link between anthropology and empire; and how do you assess something like the British Empire now, often portrayed as the worst of the Empires, and its impact, both in terms of its legacies and what it was doing at the time and anthropology’s role in that?

AM: Two parts to the question. One is anthropology and empire. Again, you have to have a double answer. There is absolutely no doubt that as Talal Asad and others have written in their books on anthropology and empire, British anthropology, which is the type I know most about, is deeply involved in the imperial expansive moment, as Jack Goody calls it. Not so much American anthropology. American anthropology is a very different kind of imperialism, the taking over of Native America. So American anthropology grew, to a considerable extent, out of going to other people’s empires or going to work with the Navaho or other American Indians; and it was the same in Canada.

But British anthropology, and in a dissimilar way, French anthropology, were different. Modern anthropology, in the more confined sense, where you have people trained as anthropologists, and calling themselves that; a formal theoretical tradition; and so on, really dates from the 1880s and E.B. Tylor. You have actual departments of anthropology in Oxford and Cambridge from about the beginning of the twentieth century – of a kind. Then comes fieldwork, the growth of Functionalism and so on.

That period, the great period of anthropology, absolutely coincides with the last two or three generations of the British Empire. And it clearly grew out of it. If you look where the anthropologists were, and what they were doing, they were the people in the periphery, on the frontiers of the British Empire – in Assam, in Africa or parts of the Pacific. They were the people who, when the British Empire rapidly expanded, collided with tribal societies in particular. And people wanted to know how to handle this, to find out about their social organisation, what they believed and above all their political system. Anthropologists quickly persuaded the powers that be that the best ways to handle this was to send an anthropologist to learn the language, to live there, and who would send reports to the colonial administrators, saying these people are like this and the best way is this. It was particularly important in the British case because there were very few British in the British Empire and they very quickly ruled it through devolved power. They worked through the local structures of power. So they worked through the chiefs and the organisations that already existed. And you could only do that if you already knew how these organisations worked. So it was absolutely essential to harness the existing system. But it was also an empire which was not ideological. The missionaries were there, but they weren’t the pushers of this empire. It was economic; and the economic led to the political, because you need to have peace. And they therefore weren't playing the game of wanting to convert these people or make them British in any way; they weren’t giving them British passports. They wanted them to be peaceful and orderly; they wanted them to pay taxes and buy British goods, and so on. But basically not to get in the way; and certainly not to maraud, because always on these borders there are hill tribes coming down and killing your tea planters or whatever they were.

So the anthropologists were part of the knowledge-gathering aspirations of the British Empire. And so they are bound to be influenced by this. There were things they could say and not say, do and not do. Even I, when I did my fieldwork in Nepal – the Empire was over, but they knew I was British and my friend was a Gurkha soldier – so I was a British officer, who had come to reconnoitre among them. I was gathering useful information and they didn’t particularly object. And then I would go home, who knows what would be useful?

So, if you’re in a critical state of mind, you can say, well they are just the lackeys or tools of the British Colonial Service. And we even trained colonial officers in Cambridge – just before the time I came to Cambridge there were courses for colonial officers going to Africa or elsewhere. So it was implicated in it; but there was a tension, because, sometimes to the dismay of the Colonial Service, anthropologists started to like the people they were working with and taking the side of the people they were working with.

3:16: They went native!

AM: They went too native sometimes. And they said, “Hang on! You can’t build that factory or that road. You can’t cut down these trees. You can’t get rid of this person.” In other words, they did this miraculous and important thing which anthropologists did, which was to say, “These guys aren’t savages. They may be simpler, and their technologies are simpler, but they’re just as clever, just as sensitive, just as human as you are. So don’t treat them as second-class. Treat them as you would your own people. They just don’t have your benefits of Western technology and education and so on.”

[GI Jones]

So anthropologists were a thorn in the side, quite often, of central colonial powers. And even the colonial officers themselves were a thorn in the side, because often they did the same. Many of the earlier anthropologists were colonial officers. One of my close friends, a senior member of the department, G.I. Jones, was a colonial officer in Southern Nigeria. I remember him telling me a very nice story about how he was free to be as sensitive and adjusted to the people as he liked, because London was a long, long way away. And he said, “They were wonderful days. It was before the telegraph or the telephone. Sometimes a runner would turn up in the compound with a forked stick with a message in it, saying, “What are you doing about this problem?!!” He wrote quickly back: “I am taking the usual action.” And the people in the Centre would say, “We don’t know what that is, but we can’t ask, really.”” So those were the days. And if you look at the work of the first two professors in my department at Cambridge, who both worked on the Nagas, Hodgson and Hutton, they were very sympathetic and understanding, and they wrote great monographs on the people. So anthropology was in a tension with Empire.

Moving on to the second part of empires I think you quote or said that “The British Empire was the worst of empires”. I don’t think that myself. I think, rather like Winston Churchill, that “it was the worst of empires, except for all the others”. In other words, if you had the invidious task of choosing bad empires and less bad empires, I would put the British as a less bad empire. And that’s for the reason I’ve mentioned; that is, it’s not an ideological empire. It’s an economic empire. Economic predation has a devastating effect. And in order to maintain the peace there were famous examples of atrocity - Amritsar is the most famous, also the crushing of the Mau Mau. Although you have these massacres, when you look at Amritsar and when you look at the size of the British Empire, over 300 years, and you think that the worst example you can get is two thousand casualties (and even so there’s a complicated story of what happened), it’s not a record like the Belgian Congo’s. It’s not a record like the Portuguese and the Spanish in South America. It’s not a record even like the French in Southeast Asia and (certainly) Algeria. In other words, it’s shocking to us, especially when you combine it with slavery and the slave trade. And yet, because it was a rational, economic matter, and there were reasons for providing peace, providing a reasonable legal system, perhaps trying to improve the communications systems, there were some features that meant that even Indians, after Independence, thought, “Well, we got some good things out of it”..

And, to end, one good index of the difference between these imperial systems is the British ‘Trust’ system. The trust system as I explained it is when a group of people would take over the raising of an heir to a big noble household; and then, when the heir was old enough and educated enough and independent enough, they would give it back. And as Maitland said, if you opened any newspaper at the end of the nineteenth century, you would always see, “We hold India in trust. One day we will fulfil our trust and Indians will be Indians again.” And that’s what Gandhi and Nehru played on and won. Basically, it wasn’t ours. This sounds patronising, but they were children. They didn’t have our technology or education and so on, but one day they would. So they were like Prep School boys or boys at public school. They were still in need of discipline and organisation. But one day they would be your equals. Now this trust idea is very different from anything you would find in the Continental empires. That’s why it was so difficult for France or Belgium or Spain to get out of their empires; because when the Vietnamese or Moroccans or anyone else wanted to be free the French would say: “What do you mean, free? You’re French, you’re our brothers, we give you passports, what more do you want?” And the reply was: “No, we want to be free. We don’t want to be French”. And this was a grave hurt and insult; and you killed them to prevent them from being free. The extraordinary thing with the British Empire was that it collapsed overnight. In two or three generations, during my lifetime, after the Second World War, it went from being the largest empire the world has ever seen to nothing. In about twenty years. And that’s because all these places said, “Hang on, you said we could be free. We’re ready. We’re good enough.” And the British said, “OK”.

And this is why, for example, when I go to China and there’s talk of a Scottish referendum and the Chinese say, “Hang on, you can’t have a referendum. They’re part of you”. And we say, “No, if they want to be Scottish, then they can be Scottish. We don’t own them. So that’s one sign. The way in which empires break up is a very good indication of the nature of what held them together. And the second thing is that after the European empires broke up – French, Spanish, Portuguese – all of the colonies became independent nations. But with the British alone, the countries said, hang on, we’re not British, but we’re part of your club, called the Commonwealth. We want to stay in your club. There was enough good to be gained from being part of the club, in terms of trade and law and education and friendship and so on. “Can we remain in the British Commonwealth?” So you have this bizarre situation where Canada, parts of Africa, Australia, India and so on remain within the British Commonwealth. Three generations on it’s weakened, but it’s still there and some still send law cases to Britain. So it’s a peculiar empire; which is not surprising, since this is a very peculiar island.

3:16: Why did anthropologists stop collecting items? You’re bringing back relics, histories, that have gone, disappeared. Before film you could bring back artefacts. But anthropologists stopped. Why did they do that? Is preserving something we ought to be doing?

AM: Well, I’ve often wondered about it. I’ve got no absolute answer. I know when it occurred, which is after the Second World War. To take the Naga people, Hutton was a big collector; Hodgson to a certain extent; Haimendorf. Malinowski, not particularly, and that might be a clue. The big anthropology museums were set up in the later nineteenth century, like the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the Pitt–Rivers Museum at Oxford, the French museums and so on. I think it’s partly a theoretical shift from the evolutionary framework, which still existed, and underpinned people like Hutton, and which was what Pitt-Rivers was particularly interested in. So if you wanted to understand even modern technology you needed to go back. So you see a line – the Pitt–Rivers is laid out in that sort of evolutionary framework, which is why it’s a wonderful museum. You see the latest of something and then you see, cruder, cruder, cruder...It was like a Darwinian museum of the evolution of the species. And that was the principle upon which museums were based until the Second World War. And therefore anthropologists would go out and would bring back material and plonk it at the right points in this evolutionary scale.

Now, after the Second World War, Edmund Leach is a good example. Before the war, he worked on the Dayaks and others; and he was collecting bits of material culture and interested in construction of canoes and so on. And even after the war, in the department at Cambridge, they taught material culture options. People like Jack Goody used to go to them and talk about the Mongolian bow–release, how you threw boomerangs and so on. They made fun of it; he and the old anthropologists talked about it; it was all ridiculous, but they had to do it and there were lectures on it. But soon afterwards it all faded away. Even when I went to the department there was a museum option, but that soon disappeared.

I think there were two things. One is anti–imperialism. It was all very well to go off and bring back Benin bronzes and Hawaiian feather capes and even simple tools in the Imperial period. But it became suspect. It was their property. And even if you had a letter, saying “I have sold this to Alan Macfarlane”... I did bring back a few things from Nepal, but I’ve never done very much with them. But basically, we don’t go around pillaging other cultures. That was a lesson of the Sixties, maybe even of the Fifties.

The second is this theoretical Functionalist thing that material culture and anthropology don’t go through these stages. Therefore, you don’t learn anything. You look at some African bow; what does it tell you about anything? Whereas if you do a study of the myths and legends and the political structure around weapons, then you might learn something.

Now Jack Goody was an inspiration because he was unusual in being really interested in technology – one of his books was on Technology, Tradition and the State in Africa. He liked things; he was interested in things. He didn’t collect for museums, really, but he encouraged me to be interested in things and technology.

Another theme, that he encouraged and which leads on from visual technology and computer technology, is all other types of technology.

3:16: You've done anthropological fieldwork in Nepal, Japan and China. You started in Nepal didn't you?

AM: I had been trained as a historian of England and by 1968 had done quite a lot of work on English social history. And then I went with my first wife to Nepal at the end of 1968 to do my conventional anthropological fieldwork.

And I arrived, and at that time you tried to find a society which was small, enclosed, a community which one could study in a functional, total, way. And as different from your own as possible; you get a lot of shock and you have to really expand your mind to encompass something which was in all respects different. So under guidance from my supervisor, who was a great anthropologist, Christoph von Fürer Haimendorf, I went to a remote village, just under the Annapurna Mountains in Highland Central Nepal. At that time there was no electricity, no roads. In another sense it wasn’t as remote as one might make out, because quite a lot of the men had been abroad for army service in the British Gurkhas. And there were radios and things like that. But it felt remote; and it was still exhibiting many features of an older period, when people believed in witches, when shamanism was prevalent, and people gathered in the evenings to dance and sing and so on. So it was sufficiently Other and distant.

It was, for me, anyway, a huge shock. Everything I’d taken for granted, more or less – my family system, my ideas of privacy, of decency, of monotheism – for all sorts of things there was suddenly an alternative, which worked perfectly well. And I liked people and admired them. They seemed to get on perfectly well without being Christians or washing every day or having locks on their doors or whatever it was. So I was challenged, as anthropologists have to be. At first it’s all chaos. It’s like a child being born. Nothing makes sense. And you don't understand a word of the language, or the culture. And then gradually, through guessing, and then testing and demonstrating, and then it fits together, gradually you begin to see the culture. Now it takes six months or nine months or a year; and by the end I could see something of it anyway.

I had to go back; and I didn't return for another sixteen years, because I had a new family and so on. I went back with Sarah in 1986. She loved it and I was amazed that they remembered me. And then it became a parallel world for me because we went back almost every year for the next eighteen years. I’ve been there twenty times in the last fifty years. So for eighteen years or so I was half in Cambridge and half in the Himalayas; and there was a productive tension. There, a shamanic, enchanted world where every rock, every tree, every house is filled with spirits. The fireplace has a spirit and the water tap has a spirit. It’s a pre-Axial Age; a very ancient, shamanic world which a number of anthropologists have documented and I experienced. And to then come back to King’s College Cambridge and teach my students was very odd, but a productive tension I think.

So that was the first questioning of my assumptions of how the world was ordered – I felt my world was somehow superior and had got it all right. But it doesn’t really change things over here because it’s like a dream. You’re the butterfly that has woken up to be a human being and this is real while you’re in it and that’s over there and a dream and then vice versa.

So it wasn’t until I went to Japan in 1990, at the invitation of the British Council as a Visiting Scholar that this changed. There, again, I went partly because I already had a sense that there was something similar about Japan. Marc Bloch in his great book Feudal Society singles out Japan as the only example he knows of a kind of feudalism that you find in Europe, centralised feudalism. The only other example he knew of in the world was in Japan. And Japan was also famous for being, like England, the first industrial society in its area; and again, two generations before anywhere else. And it was an island. And so I was curious about Japan, though I knew nothing about it. And so Sarah and I went for a wonderful six weeks.

This is not always acknowledged, but anthropology is basically about friendship. How can you get inside the minds and the hearts of another civilisation if you're not born and brought up in it and you don’t speak the language? The only way really is through friendship. That is to say, you become very close to one or two people; you build up a liking; a trust; a set of communication devices so you can talk about things in shorthand and refer back to a history of mutual understanding. And then you explore each other’s worlds in conversations and experiences over time. That’s how children learn, through building up these relationships. And that’s how the best anthropology is done. If you look at the works of Evans-Pritchard or Fürer Haimendorf or others, they say “My main source of information is X or Y” or whatever.

Well, when we went to Japan we met two scholars. One was Toshiko Nakamura, the professor who had invited me or at least suggested I came, because she’d read Marriage and Love in England. She was an early feminist and very interested in that book. She suggested to her husband, who was Professor of International Relations (later the Dean) of Hokkaido University, Kenichi Nakamura, that he invite me. So we went and they took us under their wing – they were like parents to us.

At first, we were just infants or babies; they explained that this is what you do, Alan, and this is what you don’t do. They took us to their homes and we had intensive discussions and seminars. And that would have been wonderful for six weeks. But it then happened again in 1993, 1995, 1997, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009; and they’d also come over as Visiting Fellows at Oxford at the Nissan Institute and they knew quite a bit about England. And later they started coming to Cambridge, to Clare Hall. And so we continued a conversation over a period of fifteen years where Kenichi would say, “I do not understand your religion. Why are you so religious, Alan?” And I would say, “I’m not religious. I’m an agnostic.” And he’d say, “No, you’re totally religious. Don’t you realise? Everything you do – your philosophy, the way you explain things, your arts, your aesthetics, your poetry, your garden...It’s all religious.” And I suddenly realised it was. There was Christianity everywhere.

And then I would ask him about a school class we went into on our first visit and I said, “Can I ask some questions?” and the teacher said, “Yes, of course”. I asked, “What do you hope to do when you grow up?” And they all wanted to be engineers and so on. And then I asked, “Can you ask them what their religion is?” and the teacher looked at me and said, “I can’t ask them that.”

And I thought it was because it was a taboo subject and I asked “Why not?” and she said, “Well, there’s no word for religion. They don’t know what religionmeans.” There’s no word for it in Japanese, just as there isn’t in Chinese. “What can I ask them?” And I’d just come past a lot of Shinto shrines and temples on the way to the school and they were all banging gongs. So I asked “How many of them have heard of the Buddha?” There was a Buddhist temple just outside. None of them had heard of the Buddha. And I said, “How many of you have heard of Lao-tze and Daoism?” No. “Jesus?” No. “Mohammed?” No. They had no idea; it wasn’t taught, they knew nothing. So it was a religious blank. So I said to Kenichi and Toshiko, “How do you explain this?"

And basically, through these fifteen years, they tried to understand the English – our sense of humour; our sense of identity; why we had war graves when there were no war graves in Japan – things like this. And me trying to understand the famous paradoxes of Japan as Ruth Benedict describes them in The Chrysanthemum and the Sword.

3:16: Can I interject there? In Nepal, would they have a sense of religion or not? Are they the same?

AM: Not the same, but very similar. There’s no single word. They’re the same compared to religion, as I studied it as an anthropologist without really understanding it; what Leach and other anthropologists call a ‘bundle of meanings’. It has a set of meaning constituents as we’d understand it in a monotheistic religion.

That is, it has religious rituals, trying to change the world or get in touch with the divine. We do or say certain things. It has a given set of ethics – “Thou shalt not kill”, “Thou shalt not steal” and so on. It has ideas of the afterlife and what happens after death. And it has ideas of the origins and meaning of life; where we came from and how human beings were made. So it has dogmas and theories and theology. For us, all of these are the same; you can’t have one without the other. You go into a Christian church and you have all three together.

What was amazing amongst the Gurungs and in Japan was that they split these apart. It was quite similar in both, because the Gurungs were actually Chinese; they came down from Northern China, so their religious system was quite similar. But they’d added certain things on. So in this village you would get up in the morning and you might go down to a little shrine in the fields below and you’d do a little puja or ritual of a Hindu-ish kind, to a little local god who lived under the rock there. Then you’d come back, have breakfast and throw a piece of food into the fireplace where your ancestors lived. So you had ancestor worship. Then you’d have a funeral – death is dealt with by Buddhism, often, so it might be a Buddhist funeral – champa. And in the evening, if someone were sick, you’d call in the shaman. What to us seem four different religions are practised by the same people in the same day.

Now, it’s exactly the same in Japan. The Japanese are Confucian; they’re Shinto; they’re Buddhist. Some of them are Christian. They’re not in opposition. They’re in parallel; they’re fused together. They're parts of a meal. And that means you can’t apply a group term to them _ you can talk about the “way of the gods”, but nothing more. I suddenly realised my concept of religion was very provincial and narrow.

But just to end with Japan. I’d been encountering all this oddness. It’s particularly difficult to understand because on the surface Japan looks very similar to the West. The cities look like ours, communications are very modern, life is very industrial and modern and you feel, “Why have I gone all this way just to go back to a hi-tech London?”

When you probe the kinship system it’s almost identical to the English – the terminology, the inheritance system, everything’s like the English. It’s the same “Eskimo” type kinship terminology we have. So the family system is the same. The social structure is not very different. The political system, as Bloch pointed out, is a feudal one. So politics and society are similar.

But when you get to culture – aesthetics and gardens and art, etc. – it’s totally different. When you get to, whatever you like to call it, religion, it’s totally different. So you have half similar, half absolutely different. And like all people, Japanese don’t understand how their system works. No people understands its own system. You don’t understand how England works (I don’t either) because you just take it for granted.

So for fifteen years I tried to puzzle it out and what I did is guess. I’d say, “Kenichi, is that how it is?” and he’d say, “No, no, you have no idea. It’s completely wrong.” And I said, “Well, if it’s completely wrong, what is right?” And he’d say, “Well, I don’t know, but I know that’s wrong.” Finally, in 2005, they came over and I started to write again, an attempted book on Japan. Suddenly, there was a breakthrough, like Alice’s falling through the rabbit hole. Suddenly, it all clicked; that Japan was not just different from us, it was absolutely, radically different. It’s not gone through the great Axial transformation that’s separate this world from another world. It’s not an Axial civilisation.

Jaspers had got it wrong. And that meant that this world was filled with magic. In other words, it was just like my Himalayan village, except it was a hundred and twenty million people living in huge cities. But they were all shamans. They were all from the Altaic Mountains in Northern China and they preserved, underneath the surface of Japan, a parallel world of Hogwarts, of magic. It’s a magical civilisation, pretending to be modern. This explains why their Stock Exchange and their economy are completely mysterious to the West, Why their legal system doesn’t work like ours. Why their political system....you keep hoping, and they keep trying to persuade us, that Japan is like us; but Japan is totally different.

At a deeper level they are all shamans. And I remember the ultimate triumph of an anthropologist _ when on that summer day in 2005, the Dean of Hokkaido University, a very widely read, travelled and smart gentleman, came to our tea house in our garden and said, “Alan, for the first time after reading what you’ve written, I understand myself. I am a shaman”. And when you can get the people to say you’ve got it right, you can’t get higher praise than that.

In line with what you were saying, even that, even with a hundred and twenty million people, their different worldview wasn’t enough to change my worldview here because the Japanese have always been known to be a strange island with strange people on it. And you could say, “Well, you know, it’s just the Japanese.” Like the Himalayan village and other remote leftovers, disappearing worlds. Even leading experts on Japan like Ronald Dore felt the Japanese would wake up and become like us in due course (which they won’t of course). But they can go in a ‘Pending Tray’ as an anomaly which doesn’t change the system - Kuhn’s idea.

3:16: Now if japan was a revelation, the case of China is even more dramatic. It seems to me that there needs to be greater understanding of the Chinese civilisation if we're not going to slide into another Cold War scenario.

AM: Sarah and I went to China in 1996, as tourists, because of our friend, Gerry Martin; a retired industrialist who is a very important part of my life. He suggested we go to China because he’d set up control engineering firms in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia; but he’d never been to China. It was just beginning to be possible to go to China.

So we went for ten days or two weeks, as tourists, and it was amazing. It was still, mostly, the old China. When we landed at the airport they were making a new one, but they were making it with hand tools and wheelbarrows. They didn’t have machinery. And when we went to the shops in Beijing we asked for a bottle of wine and bottles of wine and there were none until we finally tracked down Jacob’s Creek (my favourite kind) somewhere in the suburbs. The shops were dowdy, most people still rode bicycles, the clothes were dreary. But the Western hotels were posh.

We went to the north, mostly to get away from our minder, and we went to a farm. It still had much of the old feeling. But they'd started to use plastics to grow their crops under; and we asked about their lives and they said that in the last ten years it had been transformed. They now ate meat, ate reasonably, they now sent their children to school, life was far better than it was ten years ago.

So we could see; Jerry, the very perceptive industrialist, said “Alan, watch this space. These guys are going to run the world. The buildings and everything else look pretty crappy at the moment, but they’re onto something really big here. So you just watch this.” So we watched that space and we were invited to go back again in 2002, this time as academics. There was an expedition to Northern China where the Manchu had set up outposts and they stationed their troops. So we saw quite a remote part of China, in Liaoning, and it was still a matter of “don’t leave your hotel without an escort”. It was fairly rundown. But we were beginning again to get a sense of change; and Beijing was transformed by then. And we loved it.

Just at the same time I got my first Chinese PhD student. No Mainland Chinese had come to our department. But in the last six or seven years of my job I was “Mr. China”. Because I knew about Japan, they sent me anyone from China and they sent me about five students, three of them Mainland Chinese, and I became very close to them. They were lovely students. So I had the amazing privilege, each time I went back to China, of going with one of my students, who had their families distributed around China.

On the second visit, which was amazing, we went with a student whose family was in Wuhan. And then we went from Wuhan up the Three Gorges before they were finishing the flooding. And then we went to remote areas of China – Shangri-la (Diqing) and Yunnan and so on. So we saw parts of the ethnic China, but we also saw the blossoming cities, like Wuhan, which has about a million university students in about 60 universities. We went to Sichuan and Chengdu and I started forming relationships with university colleagues and students. We started to go every year _ 2003, 04, 05, 06 – I’ve been seventeen times to China.

Thanks to these students I've been almost everywhere; from the remote borders with Burma, from where tea originates, and really remote villages; to Shangri-la; to the place where there are no husbands and they don’t have the concept of marriage (Mosuo people); right to the most extraordinary cities in the world. Shenzhen, the great industrial city, transformed from 26,000 fishermen in 1978 to a city one and a half times the size of London now and equal in its wealth to Hong Kong and Taiwan combined. Where my name went up on the fourth-tallest building in the world (the Pin Ang Finance Building) a couple of years ago.

And of course again, the task is to understand it. The difficulty of understanding it is immense. It’s the size of Western Europe, Eastern Europe and Western Russia combined, geographically. It’s from Finland down to Morocco in temperature and ecology. It’s fifty-six minorities, made up of a hundred million people. It’s five thousand to ten thousand years old. It’s immensely sophisticated in its art and philosophy. So it’s impossible. On the other hand, it's terribly simple; because it's built on a very simple, structural, binary, system, of Confucian and Daoist thought; an elementary system. So both terribly difficult and terribly easy to understand at the same time.

And again, I wrote many attempts to understand it; and a couple of years ago I thought I’d just write down everything I knew. So I came up with the idea of an encyclopaedia, Understanding China A-Z. So I took subjects like “Ancestors” or “Silk Road”, or whatever, and just the writing of that sorted out a lot of the puzzles and problems in my mind. And what I discovered was that basically, as Max Weber had said, China is a magic garden. He understood China better than most, though his The Religion of China, is much criticised. But it’s a wonderful book and he understood the basic thing, which is that it’s different from us and it’s a magical world. We now have China, Japan, South America, Continental Europe, India, the Pacific cultures, on one side; and we have the Anglosphere on the other. So which is right? Is it the magical world or us?

3:16: Can you give a little more detail about the simple structure that you talk about in China? You’ve got a very interesting anthropological explanation of how simple this huge, complicated place seems to be. So perhaps you could talk a little about that, and the anthropology, the paradigms, you’ve applied to China.

AM: China is a lot of people to understand; very, very different across China and across history. Many of its “deep structures”, to use the phrase of Lévi-Strauss and others, are very old and very persistent and very simple. The deep structures of Daoism, and the language of China, and Confucianism are mainly about relations. That is to say, in Confucianism everything is about these relations. Your relationship to your father is like your relationship to the Emperor, like a woman’s relationship to a man or a younger brother’s relationship to an older brother. Everything is boiled down to sets of relationships; and all human relationships can therefore be seen as a structural relationship of that kind.

Similarly, the language - the written language certainly - which is very ancient and is the only living example of a survival of such an ancient system of writing in the world, on a large scale. It's like the ginkgo tree, which is the national tree of China, which survives from before the Ice Age; and is therefore not a tree but a fern. It has a form of leaf which is different from tree leaves. So the Chinese language is not like our language. It’s popularly called pictographic, little pictures, but it's technically logographic - one symbol has several components - and is an idea (logos), a meaning or a word. So one symbol means “man” or “tree” or whatever it is.

And again, it’s structural, because the relation between the logograph and the thing is direct. When you see the symbol of the tree, you see the tree - it’s actually a drawing of a tree as well. And you put these together in a way you don't with alphabetic scripts, into sentences and words. The language is primitive, very primitive, but very powerful, because it doesn’t distinguish between the idea, the sound of language in your mind as you read it, and the sight of it.

This makes - again, I didn't understand this until recently - Chinese art and Chinese thought absolutely different from ours in that there is no separation of sight and sound. And this separation is what characterizes the West. Leonardo da Vinci said, “Painting is mute poetry, and poetry is blind painting.” In painting, you can’t get the sound and vice versa. Chinese calligraphy is both sound and picture; and this makes it doubly powerful. I remember, we have a tea house in our garden and we had Japanese friends there. They said, “It’s wonderful, it’s more real than many Japanese tea houses. But it’s dead, Alan, there’s something missing.” And I said, “What?” And they said, “Some calligraphy. The writing would make it alive and have meaning and draw it all together”. So, in the tokonoma, the semi-shrine without a god, you have a scroll with writing. The social structure and idea systems are therefore relational and very simple.

Another breakthrough - I hope there’ll be more - is when I was giving a talk about two or three years ago in Hangzhou at Zhejiang University. An idea came into my mind and I explained it to them in the talk. Émile Durkheim is someone whose work I don’t really like very much, and I’m often very critical of; but in his work on theories of primitive religion he made an analysis of the very early religions of Australian Aborigines; and in these, and in the social structures of the Aborigines, he distinguished between two different kinds of civilisations: Aboriginal on the one hand’ and modern civilisations on the other. The Aboriginal civilisations he likened to an earthworm. Each part is complete in itself, So they are often called in anthropology segmentary structures - one segment, another segment, another segment...and the meaning of the society lies in the relations between each segment. More advanced civilisations are based on a division of labour between different parts; so you have hands, head, stomach...and none of them has any meaning or works without the other parts. So modern civilisations are held together by the tension and the functioning and the connections between specialised parts; whereas aboriginal societies are just like earthworms.

And I suddenly realised, as I was giving this talk, that China is like an earthworm; in other words, you can cut it at any point and like an earthworm it will grow back into Chinese. You can plant a Chinese in New York along with a certain number of other Chinese, and they will become China again. Or you can have a hundred million people killed by the Mongols or the Manchu or the Japanese or whoever it is - if not a hundred, then a lot - and it comes back. This is why it lasts five thousand years. You can’t destroy China short of killing every single Chinese. This is what the Americans don’t quite realise. It’s terribly strong and its terrible strength comes from its simplicity. And once you understand that you can understand a great deal about them. For example, the young Chinese who are my friends are very modern, very sophisticated - been here, been there, educated in the West - and yet there is a deep Chinese-ness to them; and their relations to me and to their parents and to other Chinese is probably not terribly different from what it was a thousand years ago. The roots have not been destroyed.

I often think of China as a massive oak tree. If you look at an oak tree, down the trunk you find there’s another oak tree underneath the earth. Its root system is as big and powerful as what’s above. And that’s the same with China. This is why, with these devastations that every two or three hundred years China goes through, where someone kills half the Chinese population, the roots are not destroyed.

And what we witnessed between 1996 and 2002 is that happening again. Because in the twenty years that we were going back from 2002 it’s all coming back. It’s not widely known that there are now many more Buddhists or Christians in China than there are members of the Communist Party - a hundred million Christians and about seventy million members of the Communist Party. And of course there’s a population of Buddhists.

And then if you look at the culture...We work with poets and I've done a lot of work with Chinese poets, painters, calligraphers, potters and, above all, musicians. If you look at the revival of Chinese opera - Southern Chinese Kunqu opera, which we brought to Cambridge - it is medieval Chinese opera. And it’s beautifully done, done as well and in the same way as it would have been done five hundred years ago. The poets are really excellent now and the painters are really good. Chinese art and culture is now possibly the best in the world. And all this has happened in the forty years since the end of Mao. Confucianism is alive and well. It’s a very philosophical place. So, all this has whizzed back. This is what Mao realised, why he had a campaign to destroy the Four Olds. He thought that by killing enough people and burning enough libraries the Olds would go. But basically, it was like Fahrenheit 451; they were in people’s hearts. You can destroy the books, but if people have internalised the book, they can speak them again.

So this is the simplicity and the strength of this ancient, ancient civilisation; and to realise that this civilization was the world’s greatest at almost every level, in its size; in its philosophy; in its arts; definitely in its technologies, until only two hundred and fifty or three hundred years ago. It’s for just a blip in its five thousand year history that the West’s overtaken it.

And it’s just returning again to what it was.

3:16: Now there were some anthropologists _ Jack Goody was one of them _ who believed China hadn’t been that different from the West. What you’re making very clear is that it’s fundamentally different. It’s a big part of what you’re saying, isn’t it?

AM: Jack Goody was a great influence on my life. He was my mentor, friend and quasi-father. And patron; I got my job through him. I have a huge respect for Jack, who died, sadly, a few years ago, and his work has greatly influenced me – on the logic of writing and so on.

Something strange happened, though, in his last ten years of writing. He was already very old, from the ages of 82 to 92. He suddenly changed what he wrote about the East, and what he’d written before, and changed his views. There were various reasons and roots for this.

He came to anthropology when he was in a POW (Prisoner of War) camp. He read two books; one was Frazer’s Golden Bough, which gave him an interest in anthropology, and the other was Gordon Childe’s Dawn of European Civilization. Gordon Childe was an archaeologist who took the long view – he was a Marxist – that basically, five thousand years ago the Bronze Age was a pan-Eurasian phenomenon. So five thousand years ago there was not much difference between Western and Eastern Eurasia. And Jack was deeply influenced by that idea. If you look at Gordon Childe, there wasn’t more than a paragraph or two about China. There hadn’t been much archaeology in China at that time. He said the Bronze Age in China and the Bronze Age in the West were curiously similar; that was about all he said. Jack had the idea that the roots of the two systems were very similar.

And then in the 1980s Jack became very critical of a Western triumphalist message of “the West is the best” e.g. E.L. Jones’ ‘The European Miracle’. There were a number of thinkers _ e.g. Rostow earlier, in Stages of Economic Growth_ who seemed to take a crude Weberian idea that to be a modern industrial society you had to be Western. It comes out of Protestant Christianity. Marx said the same thing; that the Asiatic Mode of Production could never lead into modern societies. So the East was constantly frozen in a pre-modern state and the West could become modern. And Jack, increasingly and rightly, felt this was nonsense.