Dilthey, Simmel, Nietzsche, Benjamin: Life and Relativism

Interview by Richard Marshall.

(Art: Julio Larrez)

'I believe that life is paradigmatic concept of our time. An array of disciplines under the umbrella term ‘life sciences’ dominate the theoretical discourse and have enormous practical impact. In fields such as medicine, pharmacology, and agriculture, numerous technological applications are changing our daily world as well. These applications can be understood as an indicator of the far-reaching implications that the scientific discourses on life have for society and culture. In the view of some, we are thus living in a “culture of life”.'

'Generally, life is regarded only as a prerequisite for the realization of ethically valuable qualities. I thus see neither a theoretical nor an ethical benefit to define synthetic biological systems as life.'

'To label someone a relativist is almost tantamount to making him an enemy. This politics of relativism lead to some ironies: Dilthey who used the term relativism in a pejorative sense, is regarded as a typical relativist today.'

'Although Nietzsche is often characterized as a relativist – already by his contemporaries –, he does not even acknowledge the problem of relativism in his mature works. '

'Simmel was one of the very few modern philosophers who committed himself to relativism. Especially in his Philosophy of Money, he systematically develops a relativistic world view. '

'A lot of philosophers believe that National Socialism (NS) is a form of relativism. The identification of NS with relativism is, however, misleading. Since Nazi philosophers such as Baeumler, Krieck, or Rothacker were accused of being relativists by their contemporaries, they engaged seriously with the problem of relativism. '

'The task of philosophers in a scientific context is different from the task of philosophers in a religious context. I believe that the same holds for the political context: a democratic framework fosters other philosophical activities than an aristocratic framework.'

'Nietzsche presents himself as a solitary thinker whose philosophical work takes place in separation from civic life and its amenities. He exemplifies the idea that philosophical thinking presupposes a retreat from mundane affairs by his own life and even pictures the place of knowledge in the preface of the Genealogy as “my own territory, my own soil, a whole silently growing and blossoming world”. '

'Tradition is the key concept of the late Dilthey. He explicitly rejects Nietzsche’s attempt to find the nature of things in solitary self-reflection. Against Nietzsche’s call for a fresh start of philosophy Dilthey puts forward his own conviction that “we have to take the old gods with us in any new home”.'

'There is yet another, neglected indicator of the psychological significance of dehumanization for the Nazi genocide. Dehumanization is a practical concept that guides the interaction with another group of people. It can be a forceful tool of social oppression that has a strong psychological impact on its victims. '

' From 1911 to 1915 the young Benjamin developed what one might call a “metaphysics of youth.” This metaphysics was, first and foremost, a critical theory of modern culture bringing together history, politics, and aesthetics.'

Johannes Steizinger is interested in some of the big issues emerging from 19th and the early 20th century German philosophy. Here he discusses 'knowledge of life' as a central paradigm for our time, it's application in synthetic biology, it's orientation towards relativism, why Nietzsche's perspectivism helps better understanding in this area of relativism, Simmel's relativism, his coherence theory of truth, his original answer to the self-refutation argument against relativism, whether National Socialism was a form of relativism, the long 19th century's crisis of philosophy, Nietzsche's and Dilthey's responses, Nietzsche's reclusiveness, Dilthey's historical community, the significance of dehumanisation, why Ideology matters, Benjamin's metaphysics of youth, and how he sees the role of philosophy now.

3:AM: What made you become a philosopher?

Johannes Steizinger: As a teenager, I loved to read, write, and debate. I think that my natural tendency to argue was decisive for my choice to study philosophy. Philosophy is a never-ending debate and, hence, a paradise for disagreement. I remember whole nights during my undergraduate studies in which I got lost in philosophical debates with my fellow students. No issue was too big or too small to discuss it for hours. These were the moments in which I knew that I am at the right place. It is always a sad moment when there is no real debate after a philosophical talk.

3:AM: You’ve looked at how discourses of semantics, epistemology and ethics of life in 1900 have shaped our current ‘knowledge of life’ paradigm which you say is a central paradigm for our times, something that affects the sciences, the economy, ethics and politics. So could you sketch for us what this paradigm is?

JS: Yes, I believe that life is paradigmatic concept of our time. An array of disciplines under the umbrella term ‘life sciences’ dominate the theoretical discourse and have enormous practical impact. In fields such as medicine, pharmacology, and agriculture, numerous technological applications are changing our daily world as well. These applications can be understood as an indicator of the far-reaching implications that the scientific discourses on life have for society and culture. In the view of some, we are thus living in a “culture of life”. The practical impact of scientific discourses on life also points towards an important feature of the concept in general: when life becomes an epistemological object, established oppositions such as theory and practice or nature and culture are often transcended. Naturalistic concepts of life seek to also explain social, cultural, and even ethical phenomena. This holistic dimension of the concept of life makes possible, on the other hand, so many interventions on the part of the humanities against the reductionism of naturalistic explanations.

The concurrent attempts to establish the humanities within the life sciences and to promote interdisciplinary research on life point towards an epistemic tendency of discourses on life. As soon as life is the focus of scientific research, the antithesis of the humanities and the natural sciences becomes questionable. The discourses on life around 1900 are a paradigmatic example of this tendency. In both the natural sciences and the humanities, new epistemological models arose that were mainly connected in that they strove to transcend the opposition between the natural sciences and the humanities. These methodological claims to comprehensiveness were based on the all-inclusiveness of the concept of life. Ernst Haeckel’s universal life science and Wilhelm Dilthey’s hermeneutics of life are striking examples for such epistemological models.

3:AM: One area where you’ve applied this is synthetic biology. Does the concept of life help us understand better how to evaluate synthetic biological systems? Are these systems really life, and is the ambiguity of the concept ethically problematic?

JS: Synthetic biology constitutes a special ethical challenge. Its risks are not captured by traditional technology assessment. This is because complex biological systems are difficult to predict. The more they diverge from nature, the less models for comparison are available. For a valid technology assessment it is thus important to know, as concretely as possible, how synthetic biological systems behave. I do not think that the concept of life helps to understand the activity of synthetic biological systems better. There is no precise and generally valid definition of life, not even in biology. For many scientists the possibility of a precise biological definition of life is thus not important. They regard life as a “fuzzy concept” and are satisfied with the notion that biology allows a plurality of approaches to life.

And there are indeed as many definitions as there are approaches to life. Fields such as synthetic biology, artificial life, research on the origins of life or evolutionary biology work with different definitions of life. Within these fields the old debates between reductionists and holists resurface. I do not believe that this situation can be changed. Thus, I agree with Eduard Macherywho argues that the project of defining life is either impossible or pointless. Moreover, the evaluative status of life is also controversial. Although we intuitively associate life with, there are arguments for and against its ethical relevance. A careful examination of the history of ethics would reveal that it is highly controversial whether life as such has an intrinsic value. Generally, life is regarded only as a prerequisite for the realization of ethically valuable qualities. I thus see neither a theoretical nor an ethical benefit to define synthetic biological systems as life.

3:AM: You’ve linked the orientation of the ‘philosophy of life’ approach to the development of relativism as a philosophical problem. Can you sketch for us how you see this connection developed?

JS: First, there is a historical connection. The term “philosophy of life” covers nineteenth- and early-twentieth-centuries philosophers who, despite substantive difference, agreed on their fundamental motivation: they regarded their approaches as a long-overdue renewal of philosophy, and they criticized the philosophical tradition for its allegedly one-sided emphasis on reason and rationality. In the same period, relativism emerged as an important philosophical issue that summarized the allegedly problematic consequences of modernity. When we look at the contributions of philosophers of life to the debates on relativism, we see the growing urgency of said problem. Nietzsche uses the term relativism only once. He warns in the 1870s that Schopenhauer faces the threat of skepticism and relativism because of the post-Kantian doubt whether there is truth at all. Yet the late Dilthey characterizes relativism as the challenge of the epoch in 1898. Dilthey believes that the insight into the relativity of metaphysical and religious doctrines, gives rise to an “anarchy of thinking” that endangers the normative foundation of human culture.

These debates on relativism tell us something about the general use of the term. Most philosophers consider relativism as a fundamental problem that has to be overcome. Relativism is depicted as a vague threat that endangers not only philosophy proper, but society and culture in general. Moreover, relativism is usually used in a polemical sense: relativists are always the others, the philosophical and/or political enemies. To label someone a relativist is almost tantamount to making him an enemy. This politics of relativism lead to some ironies: Dilthey who used the term relativism in a pejorative sense, is regarded as a typical relativist until today. And there are some notable exemptions: Georg Simmel called himself a relativist and he attempted to develop a consistent relativistic worldview.

3:AM: Does looking at Nietzsche’s perspectivism help us to understand better what this connection between philosophy of life and relativism is – and what the claim of relativism amounted to? Nietzsche, after all, wasn’t a relativist was he?

JS: Yes, it does. Although Nietzsche is often characterized as a relativist – already by his contemporaries –, he does not even acknowledge the problem of relativism in his mature works. This is striking because relativism was discussed as a major philosophical problem in the late 1880s. Moreover, Nietzsche loved provocations: it would have been quite a provocative statement to commit to relativism. But he did not. And, as already said, he did not even address the problem, when you would expect it. Take, e.g., Nietzsche’s rejection of universal aspirations. His critique of morality attacks every moral system that applies one evaluative framework to all humans. Contrary to the moralist’s negation of the plurality of life, Nietzsche himself embraces the particularity and diversity of perspectives. Here, Nietzsche’s perspectivism seems to get on the path towards relativism. Yet, Nietzsche does not even consider whether his affirmation of the diversity of life and its different perspectives is a relativistic view. I think this is because of Nietzsche’s reference to the concept of life. Nietzsche uses the concept of life as his fundamental standard. Nadeem Hussain has written a convincing paper about the peculiar character of this standard (“The Role of Life in the Genealogy”). It was a widespread move among philosophers of the late nineteenth century to invoke a normative facticity with the reference to life. Dilthey also refers to the concept of life to block the relativistic consequences of modern thinking.

3:AM: Returning to Georg Simmel, he was a relativist wasn’t he? Firstly, can you sketch for us how an evolutionary argument supported his relativistic stance to truth. What was the pragmatic foundation of his epistemology?

JS: Yes, Simmel was one of the very few modern philosophers who committed himself to relativism. Especially in his Philosophy of Money, he systematically develops a relativistic world view. Simmel’s relativism is a broad view that entails many kinds of relativization. From a current perspective, not all of his claims would be characterized as relativistic.

In his epistemology, Simmel attempts to show that relativism can be a coherent position. He is also one of the first modern philosophers who applies evolutionary theory to epistemology. Simmel believes that knowledge has a pragmatic foundation. The mechanisms of perception and cognition are defined as natural properties that emerge through evolution. Truth in its relation to the external world is conceived as relative to the specific needs of specific species. Simmel thus holds a pragmatic perspectivism in which the truth of a belief is determined by whether an action guided by the belief has useful consequences for a certain species. And he defines the development of a knowledge within a certain species as a process of selection. Simmel concludes that there is a plurality of pragmatically true images of the very same world. When usefulness is the key criterion, an ant and an eagle have quite different epistemic standards. But Simmel applies this pragmatic concept of truth only to the foundation of a whole set of knowledge. Nevertheless, his contemporaries regarded this pragmatic perspectivism as a dangerous species of relativism. But such evolutionary arguments do not qualify as relativistic today. Moreover, naturalized epistemology is a thriving program.

3:AM: Was his theory of truth a coherence theory?

JS: Simmel believes that after a set of knowledge has been established by usefulness, another epistemic standard guides the justification of our beliefs. Here, his coherence theory of truth comes into play. Simmel imagines our established sets of knowledge as coherent webs of belief. On this level, every belief is true only in relation to another belief. A particular belief has to cohere with the set of knowledge which it is a member to be considered as justified. Coherence is thus the key criterion for the acceptance of a belief as true. This coherence theory of truth rests on the fallibilist conviction that no belief can ever be justified in a conclusive way. Simmel accepts both the infinite regress and the justificatory circle as sufficient justification of knowledge. Coherentism is a controversial position today, especially if it contains the acceptance of circular reasoning. But note that Simmel avoids a key objection against coherentism by combining it with a pragmatic foundation of knowledge. Coherentists often face the objection that there is little reason to think that a coherent system of belief will accurately reflect the external world. Simmel avoids this “isolation objection” because each set of knowledge has an evolutionary foundation.

3:AM: So how did he face the obvious argument against all relativists, that it self refutes? How do you assess his efforts here?

JS: I believe that Simmel has an original answer the self-refutation argument. He presents his epistemic relativism as an attempt to transform the standards of epistemology. In doing this, he also seeks to re-define what it means to be true across the board. Because of his fallibilism, Simmel questions the possibility of ultimate justification in itself. He concludes that the problem with the traditional self-refutation argument is its requirements, i.e. what it accepts as a valid epistemic justification. Simmel claims that from the perspective of the self-refutation argument epistemic relativism should meet the standards of epistemic absolutism. Relativism is expected to offer an ultimate epistemological principle for its relativized position. For Simmel, it is this requirement which leads to the self-contradiction, not only in the case of relativism. After having dropped the requirement of an ultimate justification, Simmel turns the tables: He argues that other epistemological views such as dogmatism, skepticism, and criticism face a similar problems as relativism when they should clarify their own presuppositions in a conclusive way. Simmel concludes that only relativism can accept the relativity of its own justification and is thus the best epistemology available to us fallible humans.

3:AM: Was National Socialism a form of relativism? Did the Nazis actually debate this – did they take the philosophy of relativism seriously and did they actually place broader philosophical debates at the core of their ideology?

JS: A lot of philosophers believe that National Socialism (NS) is a form of relativism. The identification of NS with relativism is, however, misleading. Since Nazi philosophers such as Baeumler, Krieck, or Rothacker were accused of being relativists by their contemporaries, they engaged seriously with the problem of relativism. The actual contributions of Nazi philosophers to this debate reveal a complex self-understanding that is pretty close to the academic approaches to relativism at the time.

On the one hand, Nazi philosophy clearly has a relativistic tendency. Nazi philosophers rejected universal aspirations and absolute claims. Their emphasis on the dependence of values, knowledge, and truth on the “racial-völkisch” community is a radical form of relativization. On the other hand, Nazi philosophers rejected relativism as well. And they had systematic reasons to do so. Note that Nazi ideology was a racistanthropology. Nazi philosophers believed in an objective hierarchy of races and attempted to justify their ranking. The conviction that there is a “master race” (Herrenrasse) and that its superiority can be demonstrated is the non-relativistic core of Nazi ideology.

Most Nazi philosophers were aware of the tension between the relativistic tendency and the non-relativistic assumptions of their view. Thus, they claimed that the Nazi worldview overcomes the opposition between absolutism and relativism. They developed argumentative strategies to present NS as a third way in philosophy, but could not resolve the inner tensions of their position. Nevertheless, the general ambition to solve the problem of relativism made their ideology attractive to contemporary philosophers. Anti-relativist sentiments were a strong motivating factor for the philosophical collaboration with NS. Equating NS with relativism hence obscures an important feature of Nazi ideology that partly explains its widespread philosophical acceptance in the historical context. Many German philosophers, from most camps of early-twentieth-century philosophy, welcomed NS and attempted to show its philosophical significance.

I believe that we can learn a political lesson from this shameful episode in the modern debate on relativism: Anti-relativism is no sufficient strategy against Nazi racism or similar kinds of racism.

3:AM: The long nineteenth century saw philosophy plunged into a crisis – both about what philosophy was and what it was for. And this was due to the rise in the empirical sciences and a new understanding of history. Nietzsche and Dilthey present two different responses and you’ve written about this contrast. Nietzsche presents us with a radical break with the history of philosophy whilst Dilthey emphasises continuity. Can you say something about this and how their conceptual reorientations link to specific social images of the philosopher and why you think philosophy should be studied as a social tradition?

JS: First, I try to answer your “why”-question. I believe that a virtue of doing history of philosophy is that you can focus on issues that do not arise so easily when you are immersed in the field. The social aspect of philosophy is such an issue. When you look into the history of philosophy, it is, in my opinion, obvious that the social place of the philosopher changed quite dramatically. This is not least because both the intellectual, political, and social contexts of philosophy changed fundamentally. The task of philosophers in a scientific context is different from the task of philosophers in a religious context. I believe that the same holds for the political context: a democratic framework fosters other philosophical activities than an aristocratic framework. Moreover, the economic structure of a society influences who can become a professional philosopher. It would be odd, if the changes of the intellectual, political, and social contexts do not affect the self-understanding of philosophers and, hence, their concepts of philosophy.

But there is also another level: philosophers are social beings too. They are no brains in the vat. There are convincing social psychological studies which show that our moral intuitions are influenced by our social background. I do not see a prima facie argument why philosophers should be an exemption from this rule. I believe that the moral intuitions of a philosopher may be influenced by both her social position as a philosopher and her social origin. This assumed influence of the social background on, e.g., moral views makes the sociological perspective valuable, at least for understanding the history of philosophy. But I do not think that you can explain the views of a philosopher completely by tracing the influence of her social background. I see such a sociological investigation as a prerequisite for assessing the systematic value of a philosophy.

Coming back to the “identity crisis” of philosophy: I am interested in the meta-philosophical approaches of the late nineteenth century because here the conceptual reorientation of philosophy is closely connected with the reconsideration of the social place of the philosopher. Nietzsche and Dilthey develop not only new concepts of philosophy, but also fashion social roles for the philosopher. Nietzsche calls for a new philosophy that has yet to be established. Thus, he advocates a radical break with both the history of philosophy and its contemporary state. Moreover, Nietzsche emphasizes frequently the capacity for independence as a prerequisite of true philosophy. He characterizes this ability to set oneself apart from the spirit of the age or traditional convictions explicitly in social terms. Solitude is a key virtue of Nietzsche’s new philosophers. He presents himself as just such a solitary philosopher and repeatedly emphasizes the decisive experience of his “great liberation”. Nietzsche depicts his detachment from any institutional and social context as a prerequisite of his philosophical work.

Dilthey, on the contrary, turns to the philosophical tradition for his reorientation of philosophy. He starts with a historical understanding of philosophy and arrives at a philosophical understanding of its history. This traditionalist attitude also characterizes his understanding of the social nature of philosophy. Dilthey regards philosophy as a collective endeavor and stresses the authoritarian character of the philosophical community. It is thus no accident that Dilthey gathered a circle of pupils around him and ran a veritable philosophical workshop in Berlin.

3:AM: You say Nietzsche presents the idea of a philosophical recluse. Can you sketch for us what you mean by this?

JS: As already said, independence and solitude are key virtues of Nietzsche’s new philosopher. His self-portrayals in the prefaces of 1886 and 1887 and in Ecce Homo give us the best impression of the joyful philosophical recluse. Here, Nietzsche presents himself as a solitary thinker whose philosophical work takes place in separation from civic life and its amenities. He exemplifies the idea that philosophical thinking presupposes a retreat from mundane affairs by his own life and even pictures the place of knowledge in the preface of the Genealogy as “my own territory, my own soil, a whole silently growing and blossoming world”. Nietzsche describes his illness repeatedly as the decisive experience of his life and his retirement from his Basle professorship in 1879 as its positive turning point. He presents his retirement from the academic profession as prerequisite of both his philosophical life and thinking. Nietzsche thus cultivated the role as an outsider in an exemplary way and had tremendous success with his self-fashioning as a philosophical recluse.

3:AM: And how did Dilthey conceive his contrasting idea of philosophy as having a collective character – and of these two images of philosophy which one has been the most significant for contemporary philosophy do you think?

JS: Tradition is the key concept of the late Dilthey. He explicitly rejects Nietzsche’s attempt to find the nature of things in solitary self-reflection. Against Nietzsche’s call for a fresh start of philosophy Dilthey puts forward his own conviction that “we have to take the old gods with us in any new home”. Dilthey regards the philosophical tradition as a historical community. Its core is the relationship of the leaders of philosophical schools to their pupils. He claims that all philosophical works arise in the continuity of the philosophical tradition. Moreover, Dilthey believes that each individual thinker is determined by the philosophical past to adopt his new standpoint. He thus emphasizes the connection with the philosophical tradition in general and, in doing this, refers to a certain social imagery: No philosopher stands alone, but she is part of a historical community which shapes her thought. This is how Dilthey embraces the collective nature of philosophy and gives the latter an authoritarian touch.

I believe that individualist images are more influential in contemporary philosophy than collectivist images. Most philosophers still sit alone at their desks and publish single-authored papers. It is thus natural to imagine the philosopher as an independent and solitary thinker. Moreover, the philosophical tradition is not important in contemporary philosophy. But tradition is not the only source of a collectivist understanding of philosophy. I assume that the self-understanding of philosophers will change, when their working routines will change. Perhaps, we the beginning of such a change. More philosophers adopt scientific methods that demand division of labor, e.g. in fields such experimental philosophy. I also have the impression that collaboration becomes more important both among philosophers and also with scientists. If this trend continues, philosophy will naturally become a more collective endeavor. It will be interesting to see how the self-image of philosophers is influenced by this change.

3:AM: You’ve also sought to understand the notion of dehumanisation and with Syria and other violent conflicts seemingly always with us it seems dehumanisation is a key factor. So is dehumanisation a prerequisite of mass violence, and why do you think when we look at the Nazis for example, and the way they dehumanised groups, we need to take the ideological dimension into consideration? Can your ideas relating to Nazi dehumanisation be generalised?

JS: The significance of dehumanization is a controversial issue in the current debate about the psychological prerequisites of mass violence. I only looked at the case of National Socialism. It is hard to generalize from such a specific case. I believe that there is empirical evidence which supports the thesis that psychological dehumanization was an important feature of Nazi reality. Dehumanizing images were at the core of Nazi ideology and occurred frequently in the perpetual flow of propaganda. Moreover, party members and soldiers participated in ideological training courses that covered themes such as ‘The Jew as universal parasite’. It is very likely that such an ideological training had an impact on the psychology of perpetrators. This modest claim is supported by the psychological self-ascriptions of perpetrators who conducted the most extreme form of violence. The testimonies of camp guards often suggest that they perceived the inmates as subhumans with whom they did not share a common ground. However, these psychological self-testimonies have to be approached with some degree of caution. There are not many primary sources, and most of the primary sources that do exist are controversial. Moreover, the reliability of psychological self-knowledge is generally disputed.

There is yet another, neglected indicator of the psychological significance of dehumanization for the Nazi genocide. Dehumanization is a practical concept that guides the interaction with another group of people. It can be a forceful tool of social oppression that has a strong psychological impact on its victims. Thus, the perspective of the victims has to be taken into account, if we want to know whether their treatment involved mechanisms of dehumanization. Primo Levi’s If this is a man, written just after his release from Auschwitz, is an example of a victim’s testimony that demonstrates that the social reality of National Socialism was characterized by dehumanizing practices. Levi portrays the KZ as “a great machine to reduce us to beasts” and emphasizes the importance to fight this animalistic dehumanization. I think that it is very likely that the victimizers experienced the camp life like their victims. Nevertheless, the evidence for the ideological significance of dehumanizing images and the psychological impact of dehumanizing practices does not settle the question of the psychological motivation of individual perpetrators. We simply lack adequate psychological data to determine the psychological motives on the individual level.

Here we see a methodological reason for considering the ideological dimension of dehumanization: In historical cases, ideology is the most reliable source to study the mechanisms of dehumanization. Moreover, only a thorough analysis of the ideological foundation reveals the complex strategies of dehumanization. For understanding a case of dehumanization we have to look at what is being denied to the other, namely her humanness. Dehumanization always rest on a certain anthropological theory. And our concepts of humanity are shaped by the given intellectual and cultural context. National Socialism is an exemplary case of the anthropological foundation of dehumanization. The Nazi movement regarded itself as a political revolution which breaks with the humanist tradition and realizes a new image of the human being. The concept of race was at the core of Nazi anthropology. But it was controversial what race is, even among the key ideologues. The ideological writings of political leaders developed bluntly biological, cultural, and metaphysical concepts of race. Each version of Nazi anthropology was connected with a different strategy of dehumanization and deeply embedded in the anthropological debates at the time.

I would draw one general conclusion from my work on Nazi dehumanization. Ideology matters. It is thus important that politicians and journalists are cautious with their words, images, and concepts. Social media platforms need efficient policies regarding dehumanizing speech. Scientists and scholars should be aware of the dehumanizing potential of each definition of human nature.

3:AM: You’ve written about Benjamin on youth and the youth movement. Why are these writings so significant – and why, as you say, do they form a layer of writing which deviates strongly from the peculiarity associated with his name? Is it that difference that accounts for their being ignored or treated as largely irrelevant to his more mature writings?

JS: From 1911 to 1915 the young Benjamin developed what one might call a “metaphysics of youth.” This metaphysics was, first and foremost, a critical theory of modern culture bringing together history, politics, and aesthetics. The term “metaphysics of youth” has to be understood in two senses: Benjamin was young, when he developed this form of philosophy, and the concept of youth is the philosophical center of his earliest writings. The significance of the concept of youth marks the peculiarity of his philosophical beginnings.

Benjamin’s youth writings are so significant because they are an exemplary case of both the nature and the fate of German philosophy at the turn of the century. Starting with Nietzsche’s second Untimely Mediation, the concept of youth became connected with the hope for a spiritual renewal of society. The young Benjamin took the political aspect of the concept of youth quite seriously: He was involved in the “youth movement” (Jugendbewegung) and attempted to politically realize his philosophical ideas. Yet the start of WWI destroyed these “youthful” dreams. Benjamin abandoned his metaphysics of youth, but many of its key motifs such as the concepts of experience, awakening, and happiness returned in later writings. The analysis of Benjamin’s revision of his earliest key motifs in later writings thus illuminates his philosophical development. Later examinations of issues already discussed in his youth writings are best taken as instances of self-criticism. This understanding of the significance of Benjamin’s philosophical beginnings also sheds light on the origins of Critical Theory. As the development of Benjamin’s philosophy makes clear, Critical Theory emerged within specific political struggles that demanded a permanent adaptation of its concepts.

I believe that the ignorance of Benjamin’s youth writings follows from the common approach to the history of philosophy: when philosophers look into the history of their discipline, they mostly focus on exceptional figures. They work on Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Kant, Nietzsche etc. The individual philosopher is still the most important unit to structure the history of philosophy. The attribution of this exceptional role gives rise to an idealized image of philosophers. Their development is usually understood as maturing: there may be troublesome beginnings, questionable deviations, and elderly decline, but at the height of her intellectual strength the philosopher always finds herself, i.e. the image we associate with her place in the philosophical tradition. The ideas and endeavors which do not fit the attributed core are belittled and often excluded from the philosophical work. I believe that this approach to the history of philosophy is outdated and should be revised. I would not accept a political history that focuses solely on the exceptional deeds of a few leaders.

3:AM: Returning to the discussion at the start and the endless conflict between science and the humanities and arts how do you see the role of philosophy now? Has it a role or are the scientists the go-to guys now and we should no longer heed what the philosophers say?

JS: It depends on what you want to know. If you want to know empirical facts about something in the world, the respective special scientist is your go-to guy. But if you want to know what we should do with this knowledge, philosophers should be able to give you a good answer. Moreover, our current political situation shows that a thorough examination of basic epistemological questions such as the justification of beliefs may play a pivotal role for the future of our polities. Put briefly, there are enough tasks for philosophers that arise from the work of the natural sciences and from the requirements of democratic societies.

3:AM: And for the readers here at 3:AM, are there five books you could recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

JS: The best way into my philosophical world is reading the originals.

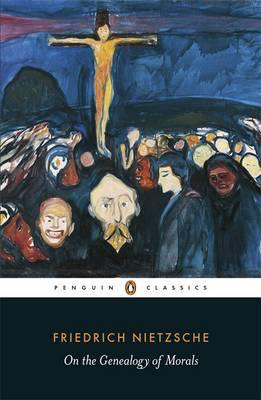

An obvious start is Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality. I believe that this famous treatise is still highly provocative and stimulating as well as tremendously well-written. Moreover, there is excellent English-speaking scholarship on Nietzsche in general and hisGenealogyin particular. Since the philosophy of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is a strange world, you need good guides.

Elizabeth Goodstein has recently published an intriguing intellectual portrait of Georg Simmel. Her book Georg Simmel and the Disciplinary Imaginary(2017) is a great introduction into Simmel’s thinking and its cultural context.

The title of Hans Sluga’s Heidegger's Crisis: Philosophy and Politics in Nazi Germany (1993) is a little misleading. His pioneering study presents an encompassing account of the connections between philosophy and National Socialism. Sluga examines the self-made crisis of German philosophy in the early twentieth century and its contribution to the success of Nazi ideology.

I believe it is important to show that the history of philosophy can be brought to bear on current debates. This is, in my opinion, especially pressing, when you are concerned with political issues such as racism and dehumanization.

Here, David Livingstone Smith Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others(2011) is an exemplary book. He connects psychological and historical approaches to the troubling phenomenon of dehumanization.

And Jason Stanley’s recently published How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them(2018) shows the eerie return of many motifs which emerged in the völkischdiscourse of the early twentieth century.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End TimesSeries: the first 302