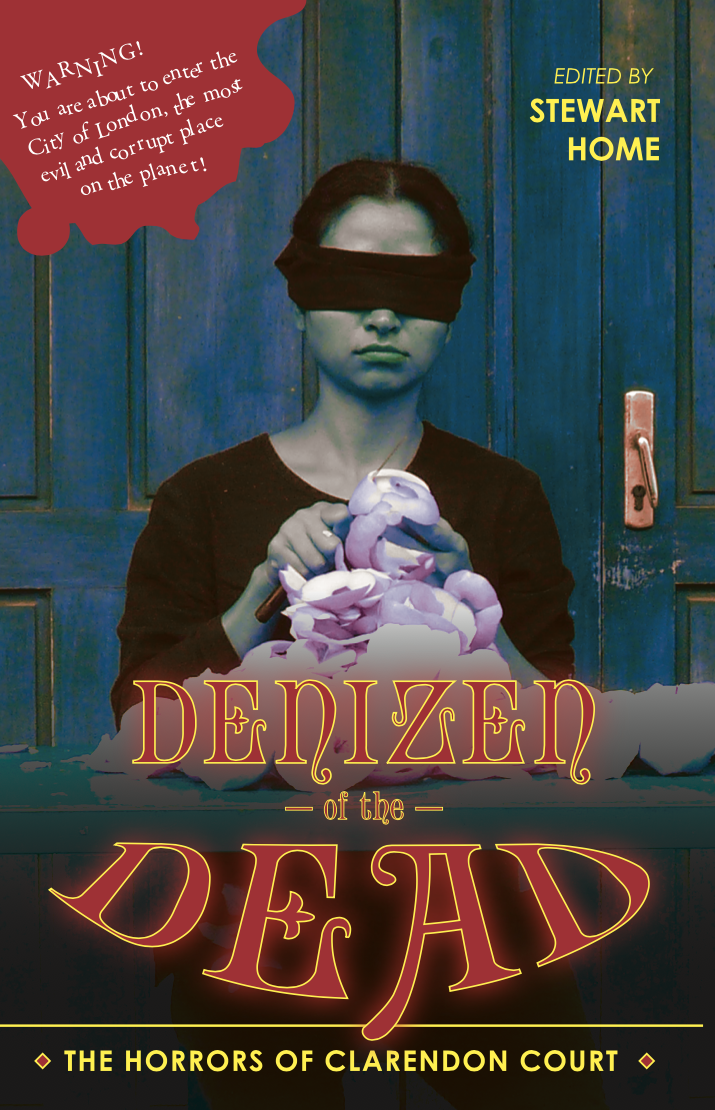

Denizen of the Dead

By Stewart Home

Denizen of the Dead: The Horrors of Clarendon Court (Cripplegate Books, published 29 August 2020)

[This is an edited version of the introduction to the volume ]

This anthology of horror stories set in and around 43 Golden Lane in central London is a continuation of a series of protests against a luxury apartment development. Taylor Wimpey’s new building at this address replaces 110 social housing units for key workers with 99 much bigger investment flats. The new apartment block is considerably larger than the one that was demolished to make way for it and now overshadows local social housing, a park and schools. Some council flats have lost 70% of the light in their living rooms and afternoon sunshine is blocked from the heavily used Fortune Street Park. While impoverished local councils often roll over for developers, the City of London which is home to this luxury development is the richest and most undemocratic council in the UK, and one which very proactively represents and lobbies for corporate interests.

The feudal local politics and potential conflict of interests that led to planning permission being granted for this development will be addressed at the end of the book. However, it is important to understand that Golden Lane is one of a number of streets that marks a boundary between the City of London and Islington. Although it was constructed in the City of London, the park and schools this development overshadows are in Islington’s Bunhill ward. The apartments in The Denizen aka Clarendon Court aka The Turd are ghost homes that even before they were built were being pre-sold off-plan to property speculators, with marketing targeting in particular the nouveau riche in South East Asia, hence a sales promotion push in places like Hong Kong. This Taylor Wimpey development is on the corner of Fann Street, at the other end of which Blake Tower was recently converted from student accommodation to luxury flats also aimed at property investors. Nearby in Moor Lane there is a luxury block known as both The Heron and Milton Court, which unlike much of the luxury property in what developers and estate agents call the City Fringe, was marketed mostly to Russian nationals rather than the new rich in China.

The names of these luxury developments are sometimes changed upon their completion because they have become infamous symbols of planning and housing policy failure. A few minutes’ walk north of Golden Lane on Central Street there is a recent construction now called Dance Square, it gained notoriety under its original name of Central Square around the time construction was completed due to the extortionately high prices of the “affordable” housing the development contained alongside its regular luxury stock. In the UK providing affordable housing simply means properties are sold at eighty percent of market value, which in a London luxury block means it is way too expensive for the people it is supposed to benefit to actually purchase. In 2012, The Guardian described the portions of Dance Square supposedly built to address local housing needs as follows: “It is, probably, the most expensive ever new-build offered by a housing association, yet it still meets the official criteria used to describe “affordable”—and qualify for taxpayer support. Part-buyers of a 25% share in a flat will have to stump up £2,322 a month to cover the rent and mortgage. The housing association says buyers will need an income of £59,000 to qualify, but in reality even that income, nearly double the London average of £33,850, will leave them with little left over after paying the bills.”

Due to the way it overshadows the surrounding area and the questionable manner in which planning permission was granted, Taylor Wimpey’s The Denizen has also achieved a level of notoriety that means its name will be changed immediately before owners take possession of their properties, probably to Clarendon Court. Despite social benefit rules, unlike Dance Square this new development contains no on site social or affordable housing—strikingly in 2019 the City of London was the only local authority in London in which no new build “affordable” housing was constructed whatsoever. Regardless of the name change from The Denizen to Clarendon Court, the stories collected here are set in the near future at 43 Golden Lane, a building locals have dubbed The Turd.

There was a broad campaign against The Turd both prior to and after the planning process. This had cultural as well as social and legal elements. Most importantly in terms of Denizen of the Dead there was an exhibition entitled Spectres of Modernism, which took the form of an architectural installation of protest banners featuring slogans by award winning artists and writers hung from the exterior of Bowater House, a block of council flats immediately opposite Taylor Wimpey’s Clarendon Court site. Some of those who participated in Spectres of Modernism are also included here, and this anthology was begun—initially as a blog—as a follow up to that project. As should be clear already, the City fringe/EC1 area is notorious for its unaffordable housing and empty ghost towers stuffed with plush investment flats. Silvertown Properties who—alongside others such as Mount Anvil— are responsible for the blight of empty apartments in EC1, trumpeted the following in the “About Us” section of their website:

'With the gentrification of Clerkenwell now complete, sizeable opportunities for residential and commercial schemes are extremely limited. There is 100 acres of land wedged between Goswell Road, City Road and Old Street which largely remains undervalued compared with its near neighbours in Islington, The City and gentrified Clerkenwell. This “area” has embarked on an ambitious renaissance and is now called Clerkenwell East. There is a high degree of obsolescence and buildings nearing the end of their useful lives, which are ready for regeneration. Islington Council along with the key stakeholder group have granted a sequence of major planning consents which are being delivered over the next 5 years. Excellent infrastructure already exists including public transport and connectivity to the key “hubs”. We ourselves have recently located our own offices to Peartree Street in Clerkenwell East.'

Surely the key stakeholder group is the local Bunhill community (the area is not called “Clerkenwell East”) and needless to say the social cleansing the likes of Silvertown Properties facilitate is not wanted by most of those who already live in the area. Like the City of London, Islington Council appears more interested in assisting the developers than listening to working-class residents. But it isn’t as if the council doesn’t know there’s a problem. The consultation document Islington Council Preventing Wasted Housing Supply Discussion Paper and Questionnaire March 2014 flags up the issue of empty ghosts homes in Dance Square and The Orchard which is directly adjacent to it:

'Initial data from the council’s Electoral Roll shows a mixed picture across Islington. The data from a selected group of major new build schemes in the southern end of the borough completed since 2008 shows a high level of possible vacancy… The price of London property when buying in other currencies has come down, making it more attainable for the upper-middle class in the Far East among others. In some Far East locations, such as Hong Kong, London represents better value than domestic property.'

Riffing on the Islington council document just quoted, an Islington Tribune article said:

'Research by estate agent Knight Frank identified the City Fringe—EC1, Old Street and City Road, all in Islington— as the prime central London location sought after by overseas buyers. In this area just under half—49 percent—of properties sold were bought by non-UK residents. Of the 51 percent of properties bought by UK residents, only 31 percent were UK nationals, meaning the bulk of property sold goes to non-UK nationals… The council report says… “The issue is not overseas ownership per se but rather new housing supply being ‘wasted’ by being left empty—so called ‘buy-to-leave’. This is particularly associated with overseas buyers, many of whom see property as an asset investment. Overseas buyers paying in cash are causing a ripple of price inflation spreading… overseas buyers are significant purchasers of properties in the £400,000 to £1m price range, which is likely to cover new developments in Islington. There appears to be a clear correlation between concentration of overseas buyers in new residential developments and the high level of vacancy in such schemes.”'

Clarendon Court is an EC1 development and while it is located within the City of London, not Islington, it provides a typical City Fringe property investment “opportunity”. EC1 is a slightly more extreme example of what’s going on across London and indeed large parts of the world. Therefore in terms of fictional explorations, The Denizen aka The Turd aka Clarendon Court can stand in for what’s wrong with property speculation pretty much anywhere. That said, a specific development is being addressed here and since property of this type in the EC1 area sells disproportionately to Chinese nationals, the characters populating the stories in the anthology reflect that. Obviously the problem these characters represent has nothing to do with their nationality but is rather rooted in the fact they are rich investors who leave their properties empty while London’s homeless are literally sleeping rough in the surrounding streets. It shouldn’t need saying there are obnoxious property investors of all nationalities and that across much of Europe and elsewhere it is the British who have a reputation for being particularly reprehensible on this score. Likewise, property speculation in Hong Kong has in recent years caused even greater suffering there than it does in London.

Moving on, I’ve loved horror stories and films since I was a child, but then I’ve also had a fascination with Hong Kong since I was twelve and became obsessed with kung fu flicks. In some ways this anthology brings these interests together. The stories here could be seen as treating Clarendon Court apartments as “hongza” properties (haunted flats). Reuters ran a story on this subject that included the following:

“The issue of a haunted flat melds the Hong Kong obsession with property with a Chinese population that tends to be superstitious and pursues ancient traditions, illustrated by the use of feng shui by many property developers to ensure that a building uses surrounding natural forces, such as mountains, wind and water, in a harmonious way. Not only does a haunted flat drag down the price of all the flats on the same floor, it can also bring down the value of apartments above and below it, according to property agents. It is commonly believed here that the trapped souls of murder victims are especially haunting, as they linger in humankind, mourning their untimely, vicious deaths and yearning to complete what they did not have time to do while they were alive.”

It would seem Taylor Wimpey didn’t take the feng shui into account when it decided to build Clarendon Court, since the development is right by the old City Mortuary. Aside from the hundreds of thousands of corpses that were laid out for examination in Golden Lane, there have been plenty of violent deaths in the area, particularly since in the past it was notorious for its brothels and the prostitutes and criminals who haunted them. More recently 22-year-old Bethany-Maria Beales fell to her death from the nineteenth floor of The Heron while visiting it in May 2018; while even closer to Clarendon Court a visitor to a flat in Great Arthur House on the Golden Lane Estate fell to her death a few years earlier, and not long before that there was a gruesome domestic murder with the body stuffed into a suitcase and left on a balcony in the same block. On the other side of Taylor Wimpey’s luxury flat development, there is an epidemic of loneliness among older Barbican residents that has resulted in a number of suicides, for example there was a jump death from a high-rise property there on 3 January 2019.

Reuters in the story I’ve quoted reported that in a heated property market, the discount on Hong Kong “hongza” flats had fallen from around 30% to 10%. Consequently, rather than its bad feng shui—those who are not planning to live in the flat they are buying likely don’t care if it’s cursed—it is more probably recent falls in the value of London investment properties and uncertainties over the future of the British economy that are going to impact sales of Clarendon Court apartments. Nonetheless it is still worth using fiction to protest against the way property investors contribute to the London housing crisis.

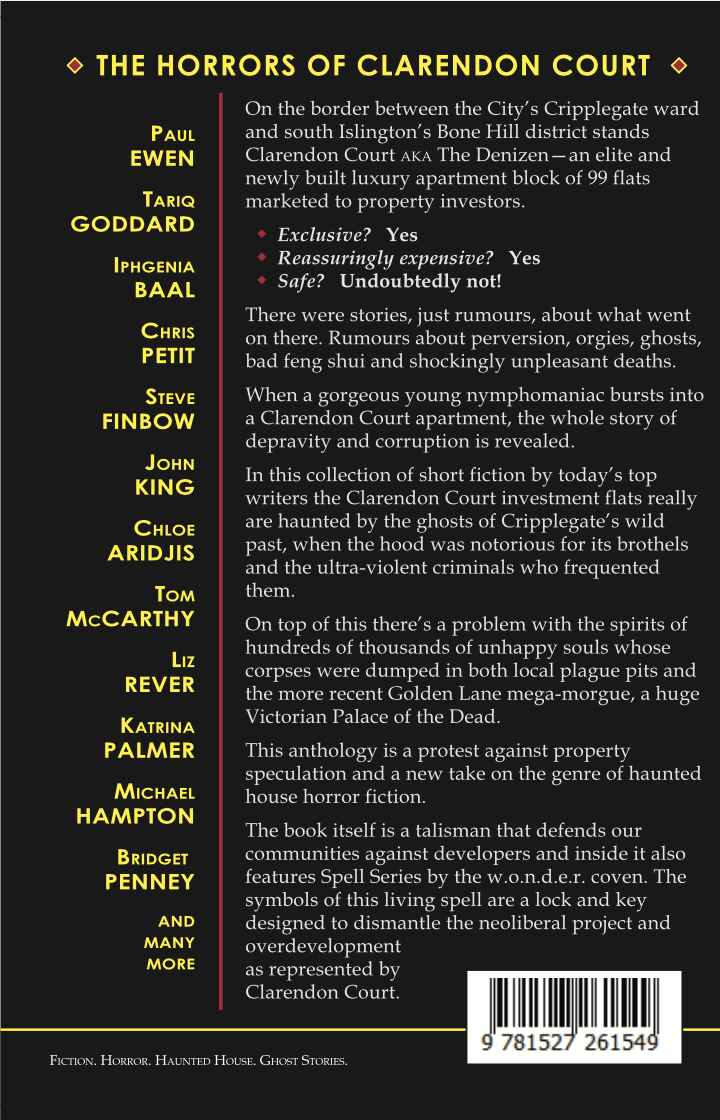

For this anthology I wanted pieces from writers who’d lived in London and understood the specifics of the situation being addressed, but at the same time I was aware that many of them had multiple commitments and therefore I was more than happy if they adapted traditional—that is to say out of copyright—horror tales. There is a range of material here some of which engages with earlier fictions in a Kathy Ackeresque way, while other pieces are wholly original. Katrina Palmer’s piece re-imagines Brian Yuzna’s horror film Society (1989), in which the rich literally feed on the poor, physically deforming and melding with each other as they suck the nutrients out of their victims in a process called “shunting”. This fabulous contribution is among the more oblique of the pieces I’ve collected in the way its author invokes the horror genre. That said, overall the anthology is intended to be both a shot in the arm for the haunted house story and a bullet in the head to property speculation!

The haunted house tale has a long history in Europe and the rest of the world. A letter from Pliny The Younger to Licinius Sura that contains a story about a haunted villa in Athens is sometimes cited as the oldest example of the genre. Obviously, genres are socially negotiated and precisely which texts are included in them changes over time—so Pliny The Younger’s 2,000-year-old piece is never gonna be the earliest haunted house tale for all people, in all places, at all times. On another note, horror stories are sometimes condemned as socially and aesthetically conservative, but while a figure like H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1947) was a political reactionary, his overblown prose remains stylistically wild because of—not despite—his insistence on using archaic forms of English. Likewise there have been modernist and other experiments with the ghost story, perhaps most famously represented by Henry James’ novella The Turn Of The Screw (1898). Thus Denizen of the Dead functions as a showcase for a variety of aesthetic approaches to the haunted house story while simultaneously taking on the mantle of social protest.

Needless to say my hope is that having put together this book of horror tales set at 43 Golden Lane, we can continue our series of ongoing cultural protests against Taylor Wimpey’s Clarendon Court development by producing an independent horror film with a story that takes place at the same location. I want to sign off with a slogan that was on a placard carried during a ritual Halloween cursing of both Clarendon Court and a proposed (re)development at the nearby Finsbury Leisure Centre in 2017—“Boo To Ghost Homes!”

About the Author

Stewart Home is an English artist, filmmaker, writer, pamphleteer, art historian, and activist. He is best known for his novels such as the non-narrative 69 Things to Do with a Dead Princess (2002), his re-imagining of the 1960s in Tainted Love (2005), and earlier parodistic pulpfictions Pure Mania, Red London, No Pity, Cunt, and Defiant Pose that pastiche the work of 1970s British skinhead pulp novel writer Richard Allen and combine it with pornography, political agit-prop, and historical references to punk rock and avant-garde art. His latest novel She's My Witch was published earlier this year.