Cosgrovia by Patrick Cosgrove (Steel Incisors, 2025)

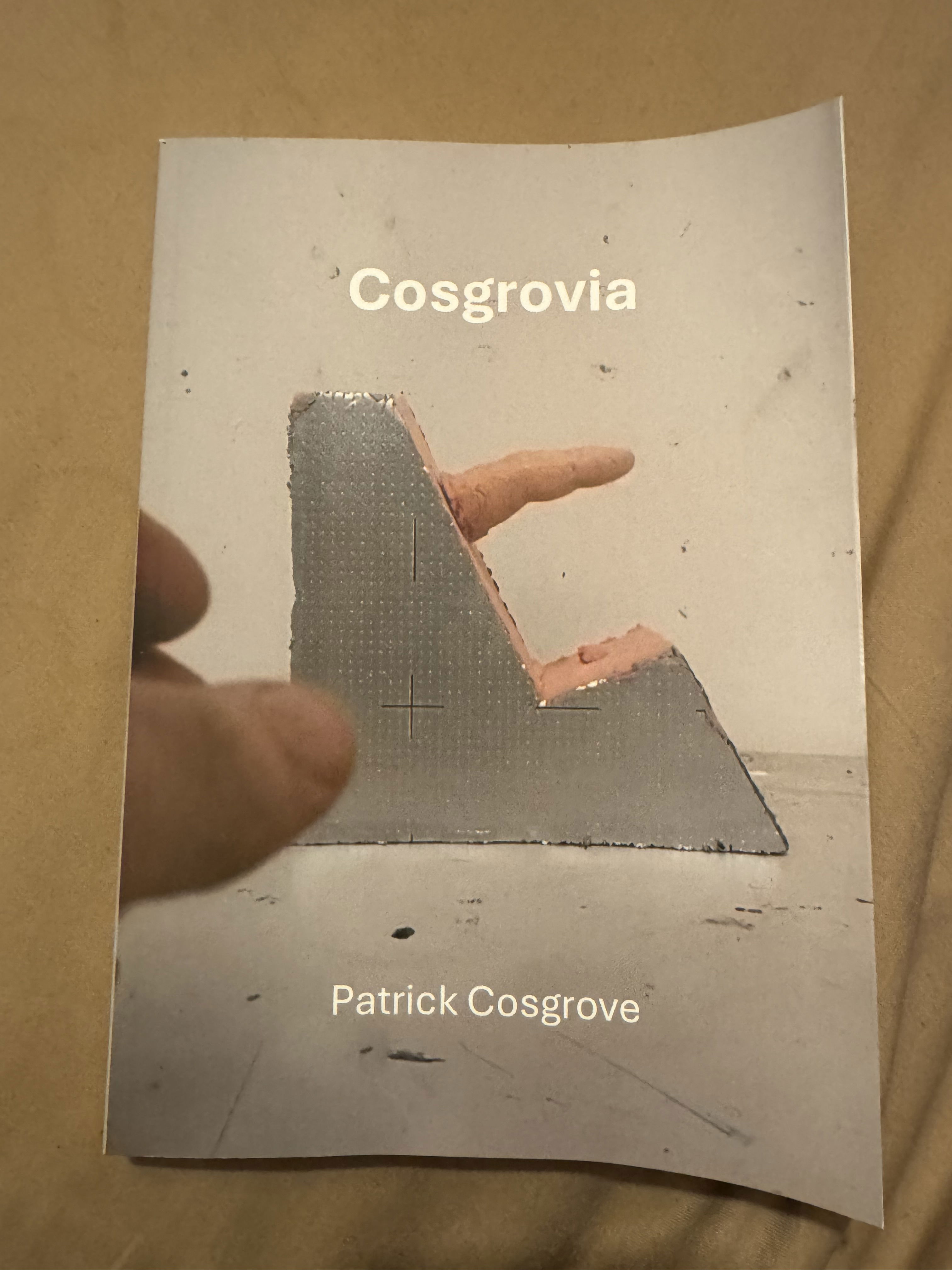

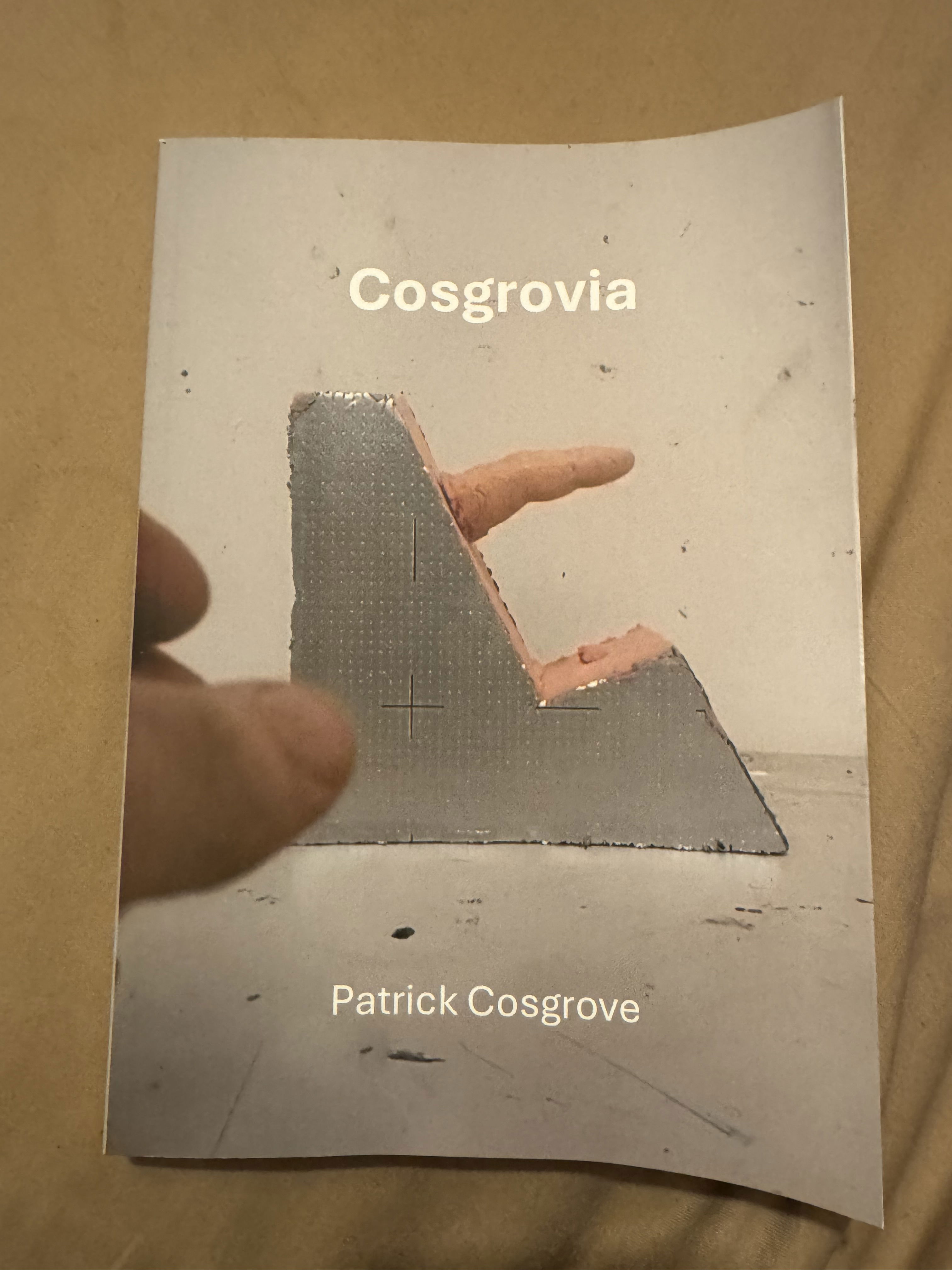

The cover of Cosgrovia does not introduce the work so much as it performs it in miniature. At first glance it looks provisional, almost apologetic, a slab of grey foam board cut at an angle, a crude pink form protruding from it, the whole thing photographed without drama against a neutral ground.

But that first glance is already wrong. The image is not casual, and it is not illustrative. It is a trap. It sets up a series of expectations about use, scale, touch, and intention, and then quietly refuses to allow any of them to settle. The object on the cover looks engineered, but badly. The grey plane resembles a model, an architectural maquette, something designed to stand in for a future structure. It has measurement marks, crosses, the ghost of planning and calibration. This is a world that promises rational construction, a world in which if you mark something carefully enough, then it will behave.

But emerging from this measured surface is a fleshy pink protrusion that immediately disrupts that promise. It is bodily without being a body, finger-like without being a finger, phallic without being functional. It does not belong to the same register as the board that supports it. The two materials coexist without agreeing on what kind of thing this is supposed to be.

Cosgrove’s work does not stage conflict between opposites. It stages non compossibility. Each element on the cover makes sense on its own. A board can be cut. A form can protrude. Measurements can be taken. Flesh can exist. What fails is the transition from one to the other. The counterfactual that ordinarily governs our engagement with objects, if this is built, then it will do something, collapses immediately. The protrusion does not activate the structure. The structure does not constrain the protrusion. They touch without relating.

The presence of the photographer’s finger at the edge of the image is a declaration. This is not a sealed art object floating in ideal space. It is something handled, tested, almost poked. The finger introduces the most basic of counterfactuals. If I touch it, something will happen. But even here the logic fails. The finger does not engage the object. It hovers, cropped, ambiguous, neither grasping nor withdrawing. Touch is suggested and withheld. The erotic charge is immediate and unresolved. This is a world in which contact is always on the verge of occurring and never completes.

This cover is an impossible world. Nothing contradictory is depicted. Everything is locally coherent. And yet the rules that normally allow inference to close are suspended. The board looks like it should ground the form. The form looks like it should be supported, used, or restrained by the board. The finger looks like it should test the relationship between them. None of this happens. The image loops. Each element reflects the others without generating progress.

The title, Cosgrovia, names a place, a polity, a constructed world. It sounds almost civic, almost utopian. But what the cover shows is a territory whose laws do not function. Measurement is present but powerless. Architecture is present but uninhabitable. The body is present but unrecognisable. This is not dystopia in the sense of a world that still looks operational, still looks designed, still invites participation, but in which participation no longer yields consequences. Patrick Cosgrove’s name at the bottom anchors the image just enough to prevent it drifting into abstraction. This is authored. It is made. That fact intensifies the unease. Someone has constructed a world in which the ordinary guarantees of making do not hold. Someone has carefully arranged materials so that desire, use, and interpretation circulate without resolution. The cover tells you, before you open the book, that you are entering a space where objects will behave like thought experiments, and thought experiments will behave like bodies. There is nothing expressive here in the conventional sense. The cover does not tell you how to feel. It does not dramatise anxiety or alienation. Instead it neutralises affect just enough to let sensation persist on its own. You are not invited to empathise with the object. You are invited to inhabit its logic. To stand where the finger stands. To hover at the threshold of contact. To experience the peculiar dread of a world in which every element seems to promise that the next step will make sense, and in which that promise is quietly, relentlessly broken. The cover teaches you how to look, how to desire, how to reason inside Cosgrovia.

You learn, immediately, that nothing here will collapse into symbolism or utility. You learn that doubles will proliferate, that structures will invite use and refuse function, that bodies will appear as fragments and fragments will behave like bodies. You learn that the most disturbing thing will not be what happens, but what never quite happens, again and again. By the time you open the book, you have already crossed into its world. Or rather, you think you have. The cover ensures that crossing itself is uncertain. You may already be inside. You may still be outside. The distinction no longer matters. That is Cosgrovia’s first move, and it is decisive.

Cosgrovia constructs a world that looks assembled rather than lived in, a world whose parts appear to have been tested against one another without ever settling into a stable order. The unease does not come from shock, grotesquerie, or symbolic excess. It comes from the sense that the world presented is locally coherent yet globally stalled, that ordinary counterfactual reasoning has been invited and then quietly disabled. Cosgrove moves away from cartoon contradictions and toward worlds in which the rules governing what follows from what no longer close.

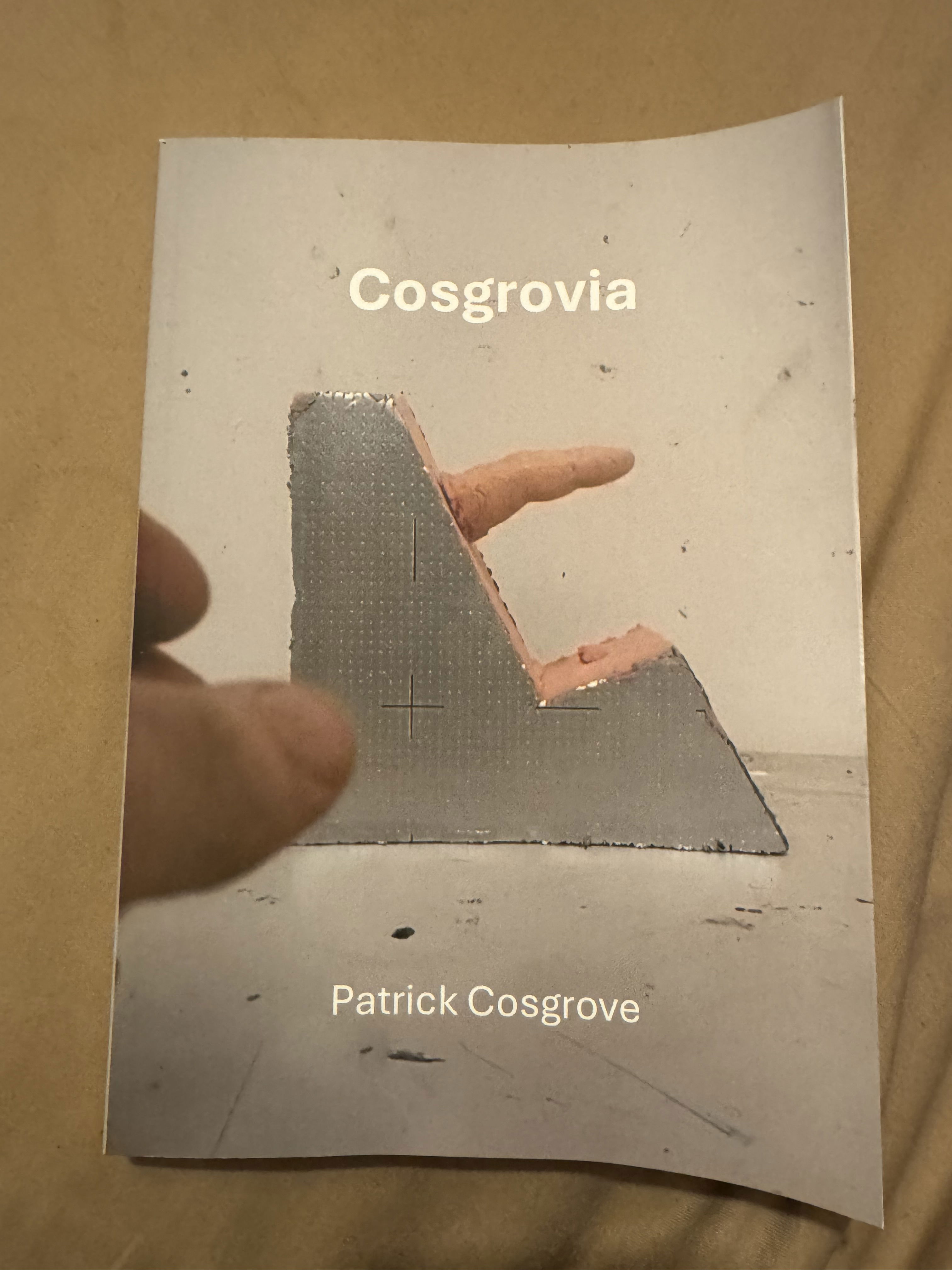

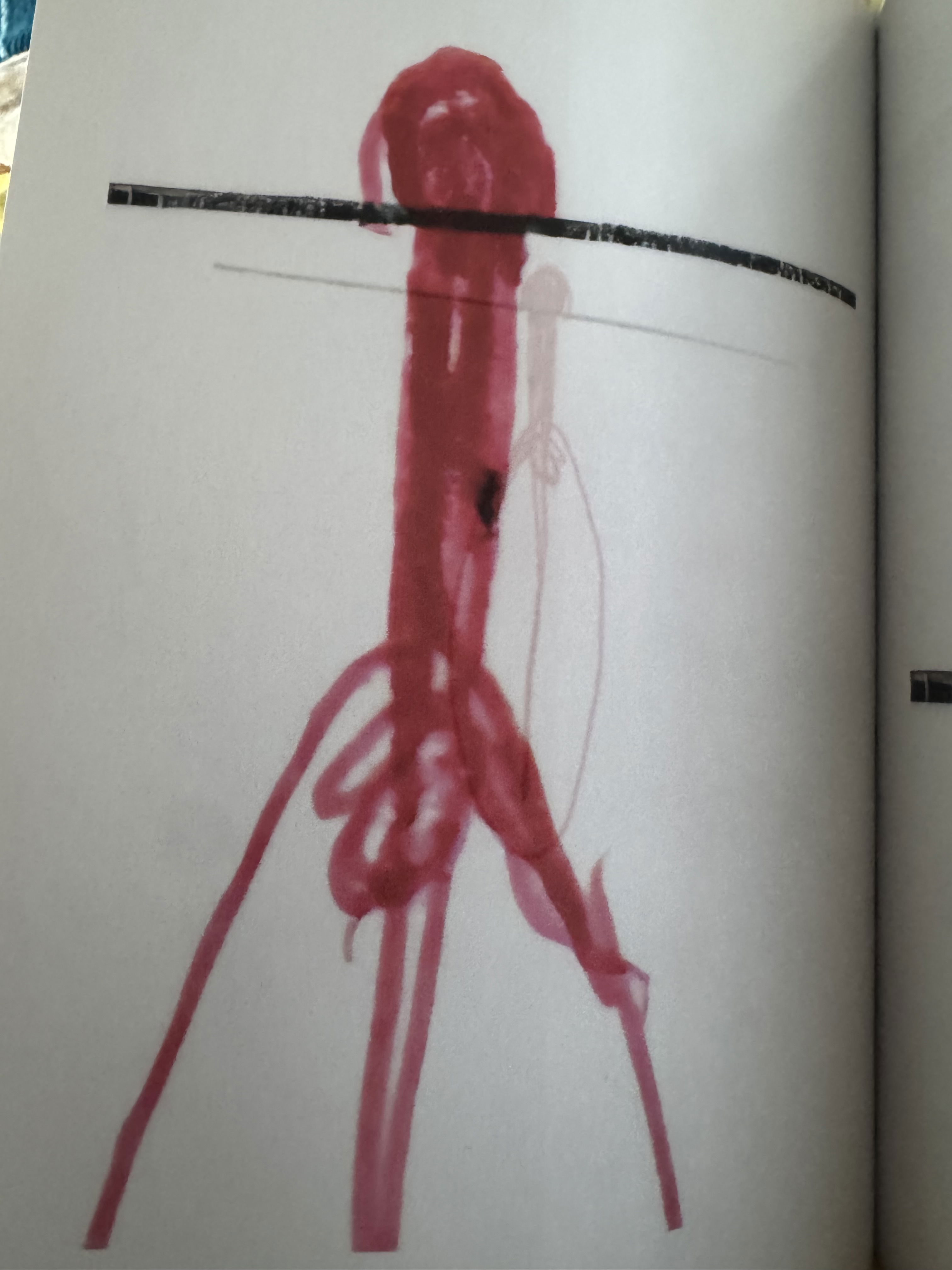

Begin with the first image, the red vertical figure intersected by a horizontal black band. It looks bodily without being a body, architectural without being a structure, surgical without being functional. The red form suggests flesh, perhaps viscera, perhaps a figure stretched into a column, but the black band cuts across it without explanation. The immediate counterfactual is irresistible. If that band were removed, then the figure would be whole. If the band were raised or lowered, the form would change. But the image refuses these inferences. The band is not an external obstruction. It is not doing anything. It does not bind, restrain, or support. It simply is. This is a case where an antecedent is imaginable but no consequent is licensed. The black band does not operate as a cause, and so the usual chain from modification to outcome fails. The image therefore functions as a looped condition. You can imagine alterations, but none of them produce a meaningful difference. The form remains caught in a suspended identity that is neither completed nor interrupted. Dread enters, not as horror but as ontological discomfort. Dread arises when an apparently decisive act fails to reorganise the world. A door is opened and nothing changes that matters. A crossing is made and the same space reappears. The red figure with the black band has that structure. The band looks like an intervention, a decisive cut, but it does not intervene. It marks without transforming. This is the appearance of a strong transformation that turns out to be weak. It preserves the configuration rather than advancing it. That is why the image feels wrong rather than violent. It gestures toward change and withholds it.

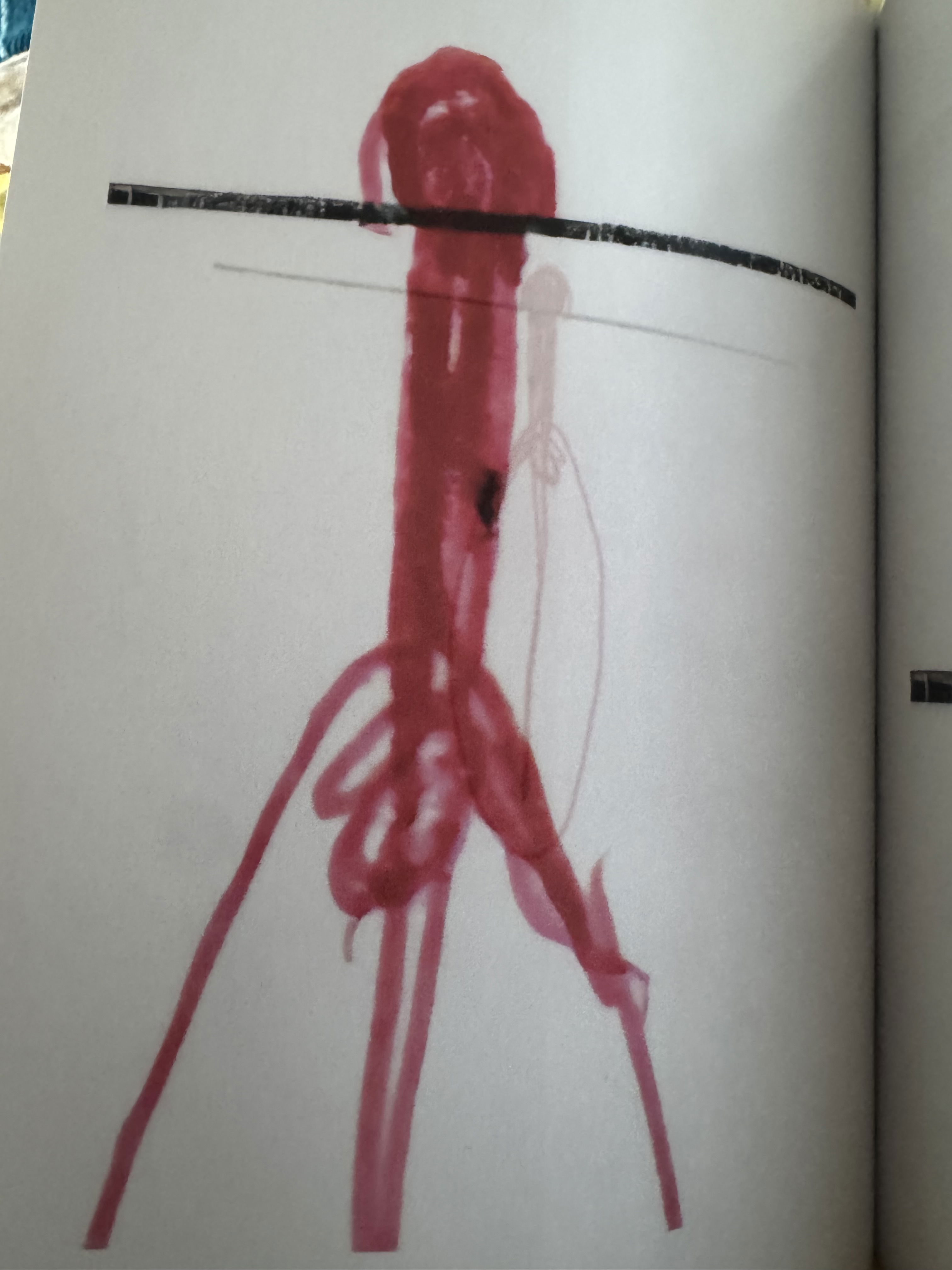

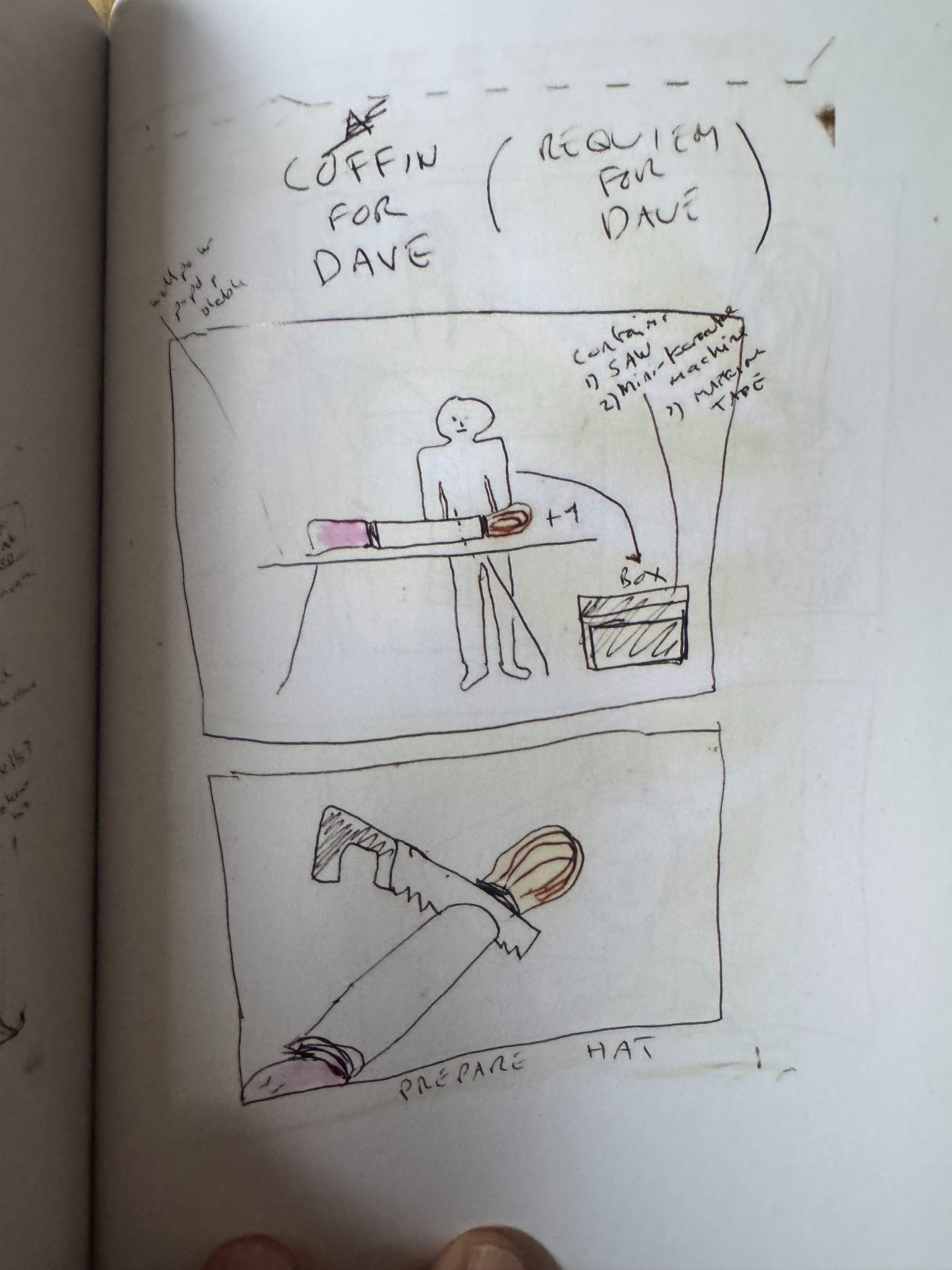

The hand drawn coffin diagram labelled “Coffin for Dave” and “Requiem for Dave”, pushes this logic into explicit counterfactual form. Here we are given not just an object but a plan, a procedural fantasy. The drawing stages a sequence. A body on a table, a saw, a box, an increment, a preparation of a hat. It reads like an instruction manual for a ritual that should culminate in closure. If you follow these steps, then something will be resolved. But the diagram sabotages its own logic. The increments do not accumulate. The saw does not cut in a way that produces a finished object. The coffin is named, but never built. The drawing remains permanently in the middle of its own process. Each step presupposes the completion it is meant to bring about. The coffin is for Dave, but Dave is not transformed by the coffin. The requiem is named, but no mourning takes place. The diagram loops back on itself. You can trace the arrows indefinitely without arriving at a final state. This is not because the artist is confused or ironic. It is because the world being constructed does not support progressive reasoning. The instructions are valid, locally intelligible, but globally non progressive. They describe a ritual that cannot complete because completion would require a kind of strong inference that the system refuses to permit.In Cosgrove’s interview discussion of Perniola, what matters is Perniola’s insistence on the neutrality of sensation, the idea that feeling can be detached from subjectivity and intention. Sensation can circulate without anchoring itself in meaning or resolution. The coffin diagram is saturated with this neutrality. It is about death, but without mourning. About preparation, but without purpose. About cutting, but without transformation. The affect is flat, almost administrative. That flatness is what makes the loop unbearable. The system allows endless weak derivations, endless redescriptions, without ever permitting a strong step that would move the situation forward.

The small sculptural assemblage with the red block, pink protrusions, white base, and orange plume, makes the same structure tactile. It looks like a totem, a figure, perhaps even a celebratory object. The plume suggests ornament or victory. But the base is cracked, the materials mismatched, the protrusions ambiguous. Again the counterfactuals line up and then fail. If the plume signifies triumph, then the base should support it. If the base is foundational, then the ornament should crown it. But the relations do not stabilise. Nothing here grounds anything else. Impossible worlds are often described as worlds where grounding relations fail. Not everything grounds something else, not everything explains something else. This sculpture feels like a grounding failure made physical. Each part leans on the others without being explained by them. The red block could be a head, a heart, a core. The pink forms could be limbs, tools, or growths. The white base could be a pedestal or residue. But no assignment holds. Every attempt to ground one part in another loops back into ambiguity. The object therefore resists being a symbol in the ordinary sense. Symbols depend on stable counterfactuals. If this stands for that, then removing it would remove that meaning. Here removal changes nothing essential. The unease comes from the impossibility of deciding which relations matter. Cosgrove’s sculpture produces the sense of ritual without ritual efficacy. Perniola’s neutrality of the aesthetic is at work here. The object is affective without being expressive. It triggers sensation without delivering meaning. That is why the loop persists. There is no interpretive exit.

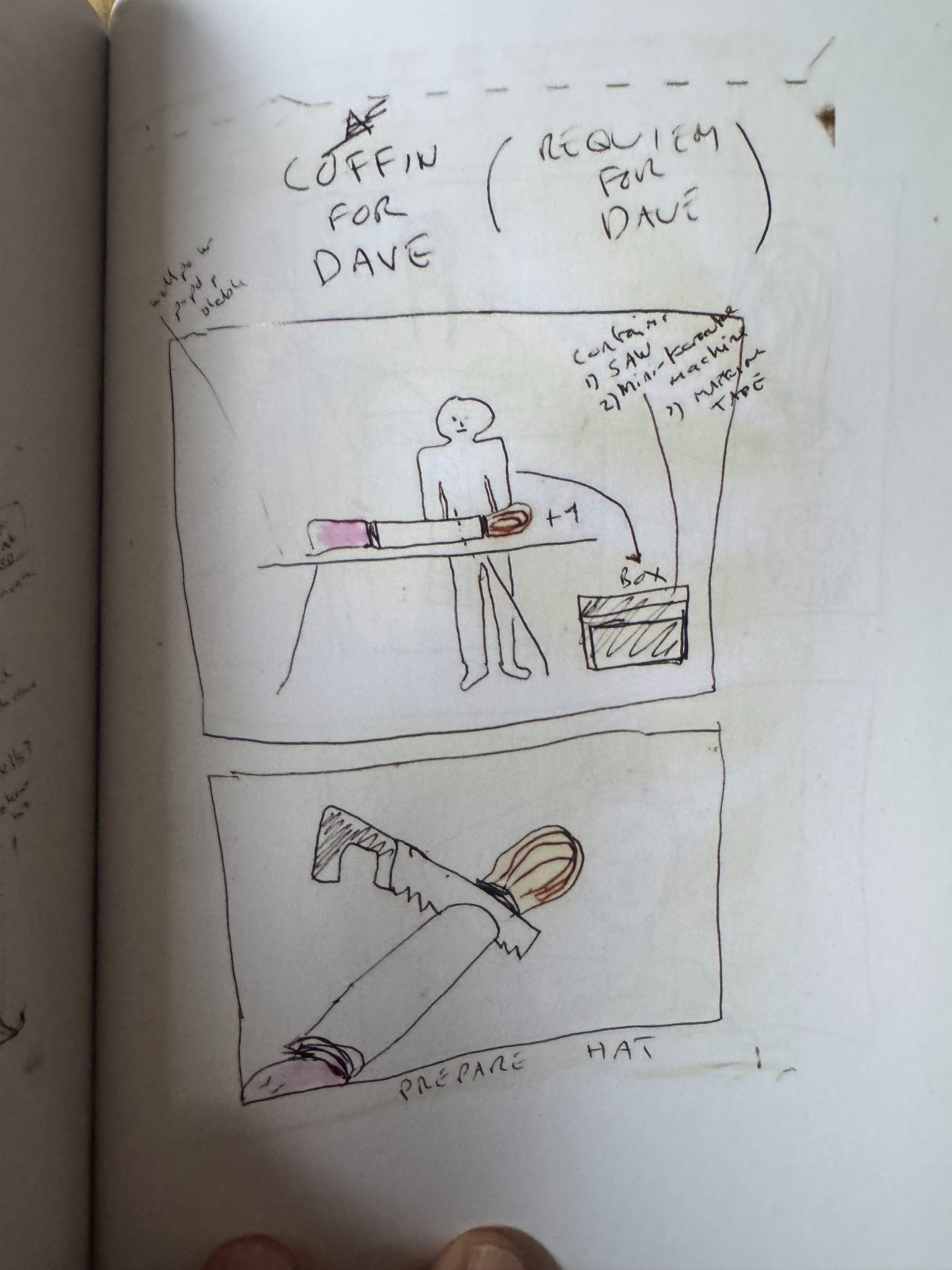

The fourth image, the circular multicoloured form with a red cylindrical protrusion, intensifies the looping structure by making it literal. The form is rotational, almost diagrammatic. Colours segment the surface, suggesting differentiation, while the protruding red cylinder suggests an axis, a handle, or a vector. The immediate thought is mechanical. If you turn this, then something will happen. If you pull or push, then the system will respond. But again, the image denies this. The protrusion does not connect to a mechanism. The coloured segments do not rotate or align. The object presents the grammar of a machine without functionality.

The fourth image, the circular multicoloured form with a red cylindrical protrusion, intensifies the looping structure by making it literal. The form is rotational, almost diagrammatic. Colours segment the surface, suggesting differentiation, while the protruding red cylinder suggests an axis, a handle, or a vector. The immediate thought is mechanical. If you turn this, then something will happen. If you pull or push, then the system will respond. But again, the image denies this. The protrusion does not connect to a mechanism. The coloured segments do not rotate or align. The object presents the grammar of a machine without functionality.

Impossibility can arise not from contradiction but from the mismatch between structural cues and inferential payoff. Here the cues scream function. The payoff never arrives. You are left holding a counterfactual that cannot be evaluated. If this were turned, then what. There is no answer, not because we lack information, but because the world does not contain the resources needed to answer. Some counterfactuals fail not because they are false, but because they are not well grounded. This resonates with Perniola’s discussion of the simulacral object, an object that simulates use without being usable. The neutrality of sensation becomes mechanical neutrality. Touching, seeing, imagining action yields nothing. The dread is procedural. You realise you are inside a system that mimics agency while cancelling it. This is why the image feels quietly oppressive. The fingertip balancing a small brown object, perhaps a nut, seed, or fragment, brings the loop into intimate scale. This is the most human image of the five we've looked at. Skin, touch, balance. The counterfactual here is almost painfully immediate. If the finger moved slightly, the object would fall. If it fell, something would change. Gravity would assert itself. Yet the photograph freezes this moment in a way that does not read as suspense. It reads as suspension without release. The object does not feel about to fall. It feels caught in a state where falling is indefinitely deferred. This is a perfect illustration of the distinction between epistemic uncertainty and modal failure. We are not uncertain about what would happen if the finger moved. We know. The problem is that the world of the image does not permit the movement to count. The falling is not part of the world being presented. It is excluded. The fingertip and the object form a looped pair, mutually defining, neither resolving into an outcome. The image is thus not about balance as a skill or a metaphor. It is about the impossibility of completing the inference from precariousness to collapse. Dread becomes almost tender. The dread is not of loss or violence but of stasis at the edge of event like where nothing happens when it should, a scream that arrives too late, a recognition that fails to crystallise. The fingertip stages an event horizon and then refuses to cross it.

The fingertip balancing a small brown object, perhaps a nut, seed, or fragment, brings the loop into intimate scale. This is the most human image of the five we've looked at. Skin, touch, balance. The counterfactual here is almost painfully immediate. If the finger moved slightly, the object would fall. If it fell, something would change. Gravity would assert itself. Yet the photograph freezes this moment in a way that does not read as suspense. It reads as suspension without release. The object does not feel about to fall. It feels caught in a state where falling is indefinitely deferred. This is a perfect illustration of the distinction between epistemic uncertainty and modal failure. We are not uncertain about what would happen if the finger moved. We know. The problem is that the world of the image does not permit the movement to count. The falling is not part of the world being presented. It is excluded. The fingertip and the object form a looped pair, mutually defining, neither resolving into an outcome. The image is thus not about balance as a skill or a metaphor. It is about the impossibility of completing the inference from precariousness to collapse. Dread becomes almost tender. The dread is not of loss or violence but of stasis at the edge of event like where nothing happens when it should, a scream that arrives too late, a recognition that fails to crystallise. The fingertip stages an event horizon and then refuses to cross it.

These are typical of the contents of this book. They are not expressions of personal anguish or symbolic puzzles to be solved. They are environments in which reasoning itself encounters a wall. The viewer keeps generating counterfactuals and keeps finding that none of them advance the situation. The loop is not explicit. It is structural. You return to the same configuration no matter which interpretive path you take. Everything remains intelligible at the surface level. Nothing breaks. But nothing progresses. Human sense-making depends on the assumption that some inferences are irreversible, that some steps cannot be undone without loss. Cosgrove’s Cosgrovia is a world in which reversibility has infected everything. Every act can be imagined as undone. Every intervention turns out to be a mark without force. Perniola’s neutrality of sensation strips these images of expressive intent. They do not ask to be decoded or empathised with. They present themselves as given. This givenness intensifies the loop. If the images were expressive, we could attribute the stasis to an attitude. Because they are neutral, the stasis belongs to the world itself. They depict the failure of grounding, the failure of counterfactual closure, the failure of progress. That is why they feel so quietly devastating. They show a world that still works, still looks composed, still invites reasoning, but has lost the capacity to move from premise to consequence in any way that matters.

Cosgrovia is organised around a constant teasing of contact that never completes, a world in which touch, penetration, incision, insertion, balance and exposure are everywhere implied and nowhere discharged. This is not coyness. It is structural. The images are built so that desire is continually generated and continually stranded.

Look again at the red vertical form cut by the black band. Read it now as bodily charge. The red is not just red. It is viscous, smeared, thickened. It has the density of something that could be wounded, opened, bled. The verticality invites anthropomorphic and phallic readings at once, but neither can stabilise. The black band is not merely a line. It is a constriction, a horizon, a gag, a censor bar, a surgical clamp. It crosses the form at precisely the point where one expects either completion or exposure. The erotic counterfactual presses immediately: if that band were lifted, something would be revealed, released, consummated. But the image refuses. The band does not cover anything in particular. It does not hide a secret. It simply interrupts. The world here is erotically charged and erotically blocked.

The problem is not that the image contradicts itself. It is that it sets up an antecedent, removal of the band, and offers no consequent that could count as fulfilment. Desire loops back into itself. You are returned to the same charged verticality, now more acute because the promise has been withdrawn. The sense is that something obscene or revelatory is about to happen, and then the cut arrives, not as repression but as ontological refusal. The cut does not protect. It nullifies.

Look at the coffin diagram and allow its erotic violence to register fully. A body on a table, limbs exposed, a saw approaching flesh, a box waiting to receive what remains. This is ritualised, procedural, strangely calm. The erotic here is not arousal but proximity, the intimacy of handling, cutting, preparing. The diagram’s crudity amplifies this. It has the quality of a child’s instruction manual for something forbidden, something half understood but obsessively rehearsed. The labels do not domesticate the act, they eroticise it by deferring it. “Coffin for Dave”, “Requiem for Dave”. The naming does not complete the ritual. It keeps it suspended. The erotic counterfactual is brutal and obvious: if the saw cut, then the body would change irreversibly. If the body were placed in the box, then death would be finalised. But nothing happens. The saw hovers forever. The box remains empty. The increments do not add up. This is a world in which the strongest imaginable transformations are reduced to weak ones. Cutting is supposed to be the paradigmatic irreversible act. Here it loops. The diagram allows infinite rehearsal without consequence. This is why the image feels perverse. Violence depends on outcome. Perversion thrives on suspended outcome. The image is saturated with acts that should be charged with horror, grief, transgression. Instead, they are flattened. The neutrality does not drain the erotic. It intensifies it by detaching it from release. Sensation circulates without anchoring itself in meaning. The viewer is forced into a position of perpetual arousal without discharge, a looping counterfactual in which the “if” is constantly articulated and constantly blocked. This is erotic dread rather than erotic pleasure, and it is structurally identical to an impossible world.

The sculptural assemblage with the plume pushes this logic into fetishistic territory. The materials matter. Soft pinks, chalky whites, a red block that could be flesh or wax, the absurdly flamboyant orange feather. This is not symbolism. It is fetish structure. Each element seems to invite handling, stroking, insertion, adornment. The plume is especially telling. Feathers belong to costumes, ceremonies, sexual display. They crown. They mark climax, elevation, triumph. But here the plume crowns nothing secure. The base is cracked, the structure unstable. The erotic promise of adornment floats above a foundation that cannot support it. If this were stable, then the plume would signify something achieved. If the plume were removed, then the object might become functional, grounded. Neither move is permitted. The plume is not detachable in any meaningful sense, and the base cannot be stabilised without dismantling the whole. The erotic here is sublimated into a permanent state of almost. Almost a body. Almost a totem. Almost a sexed figure. Almost a ritual object.

Every interpretive move returns you to the same unresolved assemblage. Desire becomes a spatial condition rather than an act. Cosgrove’s object is not teasing the viewer. It is staging a world in which teasing is all there is.

The circular multicoloured object with the red protrusion makes the erotic mechanics explicit. This is an object that looks like it wants to be used. The protrusion reads immediately as a handle, a lever, a shaft. The circular body suggests rotation, penetration, turning, grinding. The colours segment the surface like zones of sensation. Everything about it screams interaction. And yet, as with all the other images, interaction is evacuated of consequence. There is no mechanism. No opening. No response. The object is erotically legible and functionally dead.

This is an impossible world in which the grammar of use has been preserved but the ontology of effect has been removed. The counterfactual “if I push this” is meaningful in ordinary life because it presupposes a world that responds. Here, the world does not respond. The object absorbs desire without transforming it. This is fetishism stripped of satisfaction. The object does not mock desire. It does not dramatise frustration. It simply receives sensation and goes on unchanged. The dread this produces is of indifference. Cosgrove’s object is indifferent , it does not resist. It does not comply. It simply loops.

The fingertip image is where the erotic and the existential finally collapse into one another. Skin on skin. Flesh balancing object. This is intimacy reduced to its bare minimum. The erotic counterfactual could not be simpler. If the finger moved, the object would fall. That fall would be a release, a loss, a conclusion. But the image suspends that conclusion indefinitely. The object does not fall. The finger does not tremble. The moment is a suffocating calm. This reveals how deeply the erotic logic has been internalised. The body itself has become the site of looping. The finger and the object form a closed circuit. Neither dominates. Neither yields. The erotic here is not about sex at all. It is about the impossibility of letting go. We know perfectly well what would happen if the antecedent were realised, but the world of the image refuses to realise it. The world holds itself in a state of permanent near collapse. Perniola’s insistence that contemporary aesthetics is no longer about expression but about the circulation of sensation without subjectivity fits Cosgrove’s work with frightening precision. These images manufacture conditions under which desire circulates endlessly. The erotic is no longer a drive toward union or climax but a structural feature of a world that cannot close.

Across Cosgrovia, the erotic is everywhere displaced onto procedure, material, balance, interruption, and suspension. This displacement is what produces the uncanny. The viewer keeps expecting release and keeps encountering loops. It feels intolerable. Human desire is bound up with strong counterfactuals. If I do this, something will change. If I cross this threshold, I will not be the same. Cosgrove’s world denies that structure. Everything is reversible, repeatable, endlessly iterable. Even the most intimate acts are reduced to weak transformations.

This is why the work is neither pornographic nor puritanical. Pornography depends on completion. Puritanism depends on prohibition. Cosgrovia offers neither. It offers a world in which desire is structurally unfinishable. That is the deepest form of erotic dread. It is not that you cannot have what you want. It is that having or not having no longer makes a difference. These are impossible worlds not because they violate logic, but because they preserve just enough logic to keep desire alive while removing the conditions under which desire could resolve. What you are left with, after moving through these images, is not an interpretation but a condition. A world that invites touch and denies outcome. A world in which every erotic gesture is a loop. A world that is calm, procedural, neutral, and therefore unbearable. This is starvation masquerading as abundance.

Once you let that erotic looping settle, the figures in Cosgrovia begin to behave less like objects and more like unstable inhabitants of a world crowded with doubles that cannot coexist. This is where ideas of tulpas, doppelgängers, and non compossibles name something structurally precise about how these images work.

A tulpa, in its most stripped down sense, is a thought form that acquires a kind of autonomy, something generated by attention and repetition that begins to behave as if it had its own internal consistency. A tulpa is a product of iterative counterfactuality. If I attend to this form again and again, then it will stabilise. But the stabilisation is parasitic. It does not replace the world, it overlays it. You end up with two layers occupying the same space, one generated by material conditions, the other by sustained imaginative pressure.

The red vertical form crossed by the black band reads uncannily as a tulpa in this sense. It feels summoned rather than constructed. Its body is there, but its agency is spectral. It looks as though it persists only because attention has not been withdrawn. Remove the gaze and it would collapse back into paint and paper. Yet while it persists, it exerts pressure. It demands interpretation, erotic projection, bodily reading. This is tulpa logic made visual. The form exists because the counterfactual “if I keep looking, it will become something” is endlessly rehearsed. But the world refuses to allow that something to resolve. The tulpa never quite becomes a body, never quite becomes an object. It remains a quasi being, sustained by looping attention.

This is where the dread intensifies. A tulpa is always slightly out of phase with the world that hosts it. It does not quite belong, and yet it cannot be dismissed. Cosgrove’s images feel populated by these out of phase entities. They are there, insistently, but without the ontological rights of full objects. These are worlds in which entities can be locally consistent but globally incompatible with the rules that would normally anchor them. The tulpa is consistent with itself, but inconsistent with the world’s grounding relations.

The coffin diagram makes this explicit by producing what looks like a procedural tulpa. The ritual exists as a diagram, as a plan, as a repeated rehearsal. It acquires a strange autonomy. It does not need to be enacted to exert force. The diagram itself becomes the entity. The body on the table is almost secondary. The saw, the box, the increments, these are props in a ritual that feeds on its own repetition. The tulpa here is not a figure but a process. It survives precisely because it never completes. Completion would dissolve it. All this connects directly to the idea of the doppelgänger, but not in the simple sense of a double that replaces the original. A doppelgänger is not a copy but a rival. It is something that shares enough of your structure to be recognisable, but diverges at exactly the point where identity should stabilise. A doppelgänger is a non identical counterpart that is nevertheless too close to be merely similar. It occupies a space that should be unique.

Cosgrove’s objects behave like doppelgängers of familiar things. The circular multicoloured form with the red protrusion is a doppelgänger of a tool, a machine, a sex toy, a control interface. It looks like the thing it doubles, but it cannot do what the thing does. It shadows functionality without instantiating it. This is why it feels uncanny rather than simply abstract. You recognise it as something you know how to use, and then discover that your knowledge no longer applies. The object has stolen the skin of a function and left the function behind.

The double is not frightening because it is strange, but because it is almost right. Cosgrove’s forms are almost usable, almost bodily, almost ritual. They mirror the structures of action without allowing action to land. The world permits the weak equivalences, this looks like that, this resembles that, but blocks the strong equivalences that would let identity settle. The doppelgänger can exist because the system tolerates weak similarity while forbidding strong identity.

The sculptural assemblage with the plume becomes especially legible here. It reads like a doppelgänger of a figure, a fetish, a totem, perhaps even a celebrant or shamanic object. It stands upright. It is crowned. It is assembled from parts that feel bodily and ornamental. But it is not allowed to become any one of these things. Each reading cancels the others. This is not ambiguity in the sense of richness. It is non compossibility made visible.

Non compossibles are possibilities that cannot coexist in the same world, even if each is individually coherent. You can have two perfectly good possibilities that simply cannot be realised together. Cosgrove’s work is saturated with these clashes. The object cannot be both a stable base and a celebratory figure. It cannot be both a fetish and a tool. It cannot be both ornamental and foundational. Each possibility makes sense on its own. Together they jam the world. This jamming produces the erotic dread that runs through the images. Desire often involves holding multiple possibilities together. This person could be lover, threat, object of care. An object could be tool, toy, symbol. Ordinarily, contexts resolve these tensions. In Cosgrovia, they do not.

The fingertip balancing the small object is a distilled expression of non compossibility. The situation presents two possibilities that cannot coexist. The object can be balanced, or it can fall. Both are coherent. But the image insists on holding them together. The balance is shown in a way that makes the fall unavoidable in thought, yet impossible in the world of the image. This is modal paralysis. The world is caught between non compossibles and refuses to collapse into either.

The fingertip itself becomes a kind of tulpa, a hyper attended fragment of the body that has been isolated and charged until it feels autonomous. The rest of the body disappears. The finger exists as a site of sensation and control divorced from agency. It is both subject and object. It holds and is held. This doubling is erotically intense and deeply unsettling. The finger is both you and not you, a bodily doppelgänger performing an impossible task.

Across all five images, Cosgrove constructs a world crowded with these quasi beings. Objects that behave like bodies. Bodies that behave like diagrams. Diagrams that behave like rituals. Rituals that behave like objects. None of these roles are compossible, but the world insists on hosting them all at once. The world is overdetermined. Too many coherent possibilities are being forced to coexist. Perniola’s neutrality of sensation explains why this overdetermination does not explode into chaos. The sensations are flattened, evenly distributed. Nothing spikes into climax or catastrophe. Everything is held at the same intensity. This evenness allows the non compossibles to persist side by side without resolution. It is a cold world, but not a dead one. Sensation continues to circulate. Desire continues to generate counterfactuals. The world simply refuses to honour them.

This is a Lynchean dread in metaphysical rather than narrative key. You are not afraid of what will happen. You are afraid that nothing will ever be allowed to happen in the way it should. The doubles will never resolve into originals. The tulpas will never dissolve. The non compossibles will never be separated. Cosgrovia is staging a world in which identity, desire, and action have all been duplicated without being grounded. Everything has a double and no original. Everything invites a counterfactual and refuses its completion. The erotic becomes the engine of this refusal, because erotic desire is the place where we most insist that difference should make a difference. Here it does not.

What remains is a world that is saturated, crowded, and yet empty of progress. A world of looping doubles, summoned tulpas, and non compossible possibilities stacked on top of one another. The dread comes from recognising that nothing in this world is broken. It is working exactly as it is structured to work.