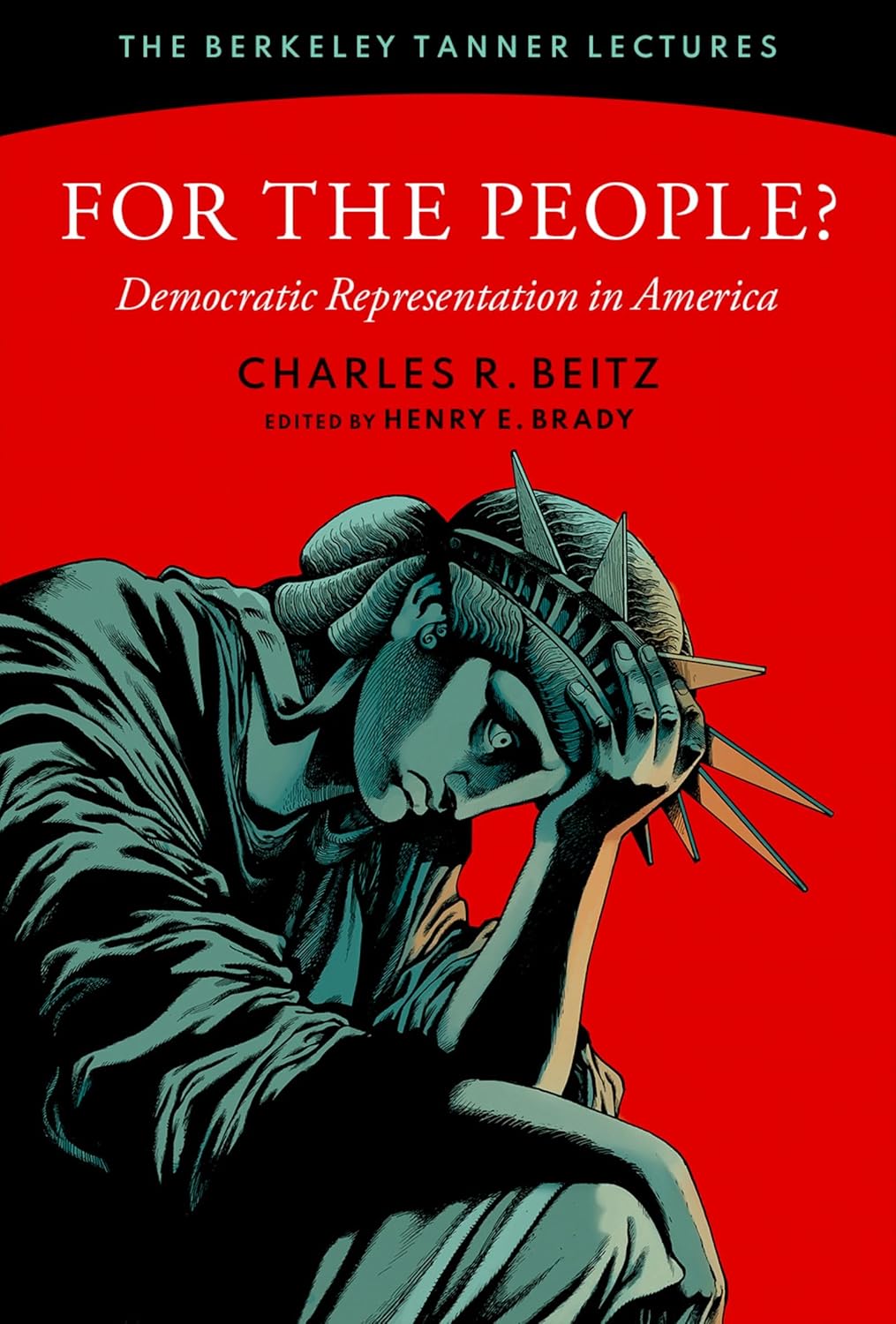

Charles R. Beitz, For the People: Democratic Representation in America

Charles R. Beitz, For the People: Democratic Representation in America (Oxford University Press, 2024)

Like nearly every political scientist in the known universe, Princeton’s Professor Charles Beitz has no doubt that the (I would say “what little”) democracy there was in the United States prior to the turn of the millennium is on the verge of disappearing entirely. The difference is that Beitz is not entirely satisfied with the measures that can be used to verify this nearly universal impression among political scientists. So, in the Tanner Lectures reproduced in this slim, lucid volume, he makes an impressive attempt to understand both what would make for a clearly democratic jurisdiction, and the precise measurements that can be used to determine whether anyone’s intuitions about the level of democracy–or its current course–are appropriate. He is assisted in this effort by the excellent commentary provided by three fellow scholars, Martin Gilens, Pamela S. Karlan, and Jane Mansbridge.*

I will not have much to say about the second of the two lectures, “Regulating Rivalry,” that is included here. It’s a careful discussion of the sort of political contests that can be said to be good for the electorate–and of how and when the battles between candidates or parties can go “off the rails.” Beitz’s subtle categorizations of the benefits that political parties and interest groups can provide as well as the dangers they pose make the piece a worthy successor to several of Schattschneider’s brilliant classical discussions of those issues. Political scientists and party functionaries should read it with care. Elected officials too.

Beitz claims that the most important reason we should get contestation rules right may be that corrections in areas like campaign finance are needed to help undo legislative gridlock, which has gotten worse and worse over the past 30 years. He writes that “notions of legislative effectiveness—tentatively, a capacity to legislate successfully—tend not to be prominent in democratic theory.” I’m not sure I agree with that particular sentiment, especially given Samuel Issacharoff’s recent book,$ but it certainly seems correct that citizens are quite likely to be harmed by faulty campaign rules, and that this harm results largely from the decreased legislative effectiveness that eventually ensues from election fights thought to be unfair. The analysis here is quite compelling.

I have somewhat more to say about Beitz’s opening lecture, “Intimations of Failure,” and it is not entirely favorable. Beitz notes that his concerns are not “mainly a matter of settling the facts. The question involves their normative significance—it is diagnostic…” He follows this up by asking, “What do these diagnoses suggest about the requirements of fair and effective representation?” Presumably, what he calls “fair and effective representation” is what his readers will understand to be generated by acceptable democratic practices. No doubt that will be true of many readers, but, as Beitz understands, it’s not a matter that can be skipped over, because there is a central impediment to anything like general agreement on the nature of “acceptable democracy.”

Back in 1959, a relatively obscure philosopher named Henry Johnstone wrote a book called Philosophy and Argument in which he claimed that a good deal of quite competent philosophy is basically ad hominem. That may sound harsh as well as unreasonable. But let me try to explain its plausibility by connecting it to Beitz and democratic theory. According to the views of “responsive” democrats, a well-run, self-governed jurisdiction must at least try to effect policies that the citizenry wants. That requires a sort of congruence between the desires of the populace and the policymaking work of its representatives. On this theory (and it is one to which I adhere🗡) the position is foundational–responsiveness to the desires of the populace is not only essential to the concept of democracy, but is the main reason why self-government is attractive in the first place. It thus involves scrapping the idea that what makes democracy good or bad is its output, the results it produces for a particular group.

A good deal of Beitz’s first lecture is devoted to the claim that attempts at congruence are a confused manner of advocating for real democracy. For on his view the point of democracy is actually to attempt to represent not what anybody wants (or says they want), but what’s actually in their best interests. And the latter is something for which it does make sense to measure outputs–how people are doing according to this or that standard. On that view, attempts to achieve congruence can be basically ignored in favor of ostensibly beneficial “system” attributes that may well be orthogonal to what the electorate say they want. Thus, in Johnstone’s terms, Beitz can be said to be making the ad hominem claim that congruence supporters are not authentic democrats.

The obvious response to this is that nobody should be thought to be in a better position to say “what is good for people” than those people are themselves. Congruence backers are thus likely to respond in kind with the also ad hominem remark that Beitz’s book seems to them an example of plain advocacy for an elitist anti-majoritarianism.

Now, I have no wish to suggest that Beitz’s heart is in the wrong place. Like Madison, Tocqueville, Mill and many other distinguished scholars, he worries that majorities are dangerous–especially when uneducated and fired up. That this is a particular concern of Beitz’s is demonstrated by the fact that when an audience member asks him what is wrong with Mill’s view that more educated voters should get more votes, Beitz suggests that Mill’s idea might be good if there were a sensible way to determine who really are the most intelligent voters. The tell is that he shows no similar concerns regarding what is to count as being in the best interests of those same individuals. (Perhaps a committee of political science professors at Ivy League schools should be trusted to handle that matter?)

Again, fears of majority tyranny aren’t unreasonable. Minority groups are discriminated against all over the world and have been since the dawn of civilization. So, I do not deny that there must be limits to what majorities can be allowed to do. If we exalt democracy, we must also exalt equal protection, non-discrimination, and a bundle of political rights. Nothing that ought to be called “democracy” can exist without all of these. And, of course, we cannot allow even a nearly unanimous majority to upend democracy itself. But these rights should be understood to be “inalienable,” not because they are endowed by anybody’s creator, but because we cannot have democracy without them, and, again, self-government is thought to be intrinsically good, regardless of what it brings. That is, it is democracy itself that is the intrinsic good and the so-called rights are merely instrumental.

Throughout his lectures, Beitz’s quite reasonable distrust of unlimited, right-wing populism leads him to what seems to me a fear-filled hope of more effective Madisonian constraints. This, in spite of the fact that, to my way of thinking at least, it is precisely such constraints that have always kept democracy in America at arm’s length. There are new constitutional constraints needed, but they are not Madisonian at all. They have nothing to do with separation of powers, federalism, cross cutting, or the like. They are not limitations, but rather items that are essential to the exaltation of authentic democracy.

Beitz wants representation to be “fair,” and thinks that empirical evidence to the effect that, e.g., Blacks almost never get what they vote for suggests unfairness, but he again denies that this is a matter of that group very seldom getting what they want. On his view, any such reliance on congruence is a sort of “scaling up” of a systemic representative democracy from a model based on achieving individual desires, an error that he takes to ignore numerous institutional dimensions of representation, including trusteeship, deliberative possibilities for improvements, and the fact that the policy perspectives of representatives often have effects on the views of their constituents. Instead, he takes the unfairness to the Black electorate to be demonstrated simply by that cohort’s lack of effectiveness (i.e., tendency to lose) when contrasted with how other groups have done. He writes, for example, that

Unprecedented levels of elite polarization, extreme partisan gerrymandering, weakened party institutions, easing of restrictions on campaign finance, fragmentation of the public sphere, and other forces—all in the context of rising levels of economic inequality and the stubborn persistence of racial resentment—have produced dysfunction that subverts healthy political competition.

But, one might ask, why anyone should care about any of those alleged ills if the point of democracy is not to get people what they want in the first place. How would Beitz test the veracity of (the clearly discriminatory) claim that Blacks have just tended to be more confused about what’s actually in their interest?

As indicated, I don’t think Beitz is entirely mistaken in his specification of appropriate reservations regarding responsiveness, but in my view the solution to such worries cannot be expected to result from committee government by experts, but rather from robust recall and referendum (not initiative petition!) provisions. Those, of course. suppose that it really is the electorate’s wants that matter. It is a view that alleges that three years of immovable leaders or policies having 30% approval ratings can never be democratic. Naturally, however, nobody who has doubts about the essential standing of congruence is likely to support such measures.

Can recall be thought to somehow prevent majorities from discriminating against minority groups? Of course not. My point is that if democracy is about anything, it is about self-government–a citizenry’s right to get the representatives and policies they want, or at least force their government to try. As I have said over and over again for at least a decade, if a group of people is generally stupid and cruel, a competent democratic system should be expected to produce a generally cruel, stupid jurisdiction. The idea that a kinder place with, say, a more equitable distribution of wealth or more sensible attitudes regarding climate change might be produced by democratic reforms alone is absurd and essentially anti-democratic on its face. To the extent that any such jurisdiction becomes a more attractive place in spite of the nasty views of the populace there, it can only have become less democratic.

Again, I can’t deny that this is largely an ad hominem take on Beitz’s lectures. I am truly sorry about this, because I have enjoyed his book and I believe everyone with an interest in these matters should read it, if for his granular distinctions (and the excellent commentaries) alone. But there seems to me to be something like Andrew Sabl’s# two theoretical “cultures” at play here. Beitz is an occupant of the fearful, elitist one that has had its way in the U.S. since the “founding fathers” and their Federalist Papers. That group has mostly found opposition among various Rousseauvian fans of direct action, anti-democracy Leninists, and right-wing followers of Dostoevsky or Schmitt. I belong to a less careful, even perhaps blindly utopian “culture.” As I have tried to show in my book and in essay after essay subsequently, there is another way to oppose patronizing elitism. It calls for a populism that is “distilled.”

-------------------------------------------------

*Beitz’s lectures along with the commentaries may be also watched on YouTube.

$I have reviewed Issacharoff’s book here at 3:16 AM.

🗡See, e.g., this and this.

#See his “The Two Cultures of Democratic Theory: Responsiveness, Democratic Quality, and the Empirical-Normative Divide” (2015). I don’t deny that in this paper Sabl takes a position that is closer to Beitz’s than to my own. In fact, I think that is generally the case generally with APSA publications.

About the Author

Walter Horn is a philosopher of politics and epistemology.

His 3:16 interview is here.

Other Hornbook of Democracy Book Reviews

His blog is here