Brief Notes on Audrey Szasz: “If You Can Bear This Then You’ll Pass the Test.”

She is the novelist of filth gone far from home base and the ivory towers of holes, missing time, fucking and masturbation, leather partying, whips and furs and all that insignia . She lowers the tone. She has her powers of subjection and all the disturbing elements. She is masterfully repetitive. She casts time and the body to the outside. Her essence is the canceling of natalist fantasies. She is the living writer (before her there have for sure been dead ones) who destines people to higher things than growth. Tick tock is to no avail.

This is the party that’ll get you in the end and no one will be left alive enough. She can write of loss, sacrifice, expenditure, waste, death, torture in terms of interminal goals and motivational fields, a kind of rubbed excitement from under traumatic bedsheets. The conspicuous consumption of agonies, of thrived torture, of the lure of having no return on anything done, is a strange man, an executed woman, a shameless child dressed within or without the hallucinatory visuals and twists of orgasm frenzy and kill secretions.

Reading her is to attend to excesses, bestial monstrosities, forces and energies and experiments of sacred horror done as brimmed ordeal. She is sly and funny. That’s how she does her expressiveness and keeps order. It’s how she combines a playful Ruskin Gothic with Bataille Expenditure like a double entry sheet done by a playfully sexualized Lolita with a knife held between her legs.

Ruskin’s Gothic is ‘a magnificent enthusiasm, which feels as if it could never do enough to reach the fullness of its ideal: an unselfishness of sacrifice, which would rather cast fruitless labour before the alter than stand idle in the market.’ It’s a fretwork, more than filigree but is also worry and wearing and a threatened deferment of the whole damn snuff ceremony.

Bataille’s Expenditure is an excess of utility, unpurified expressions, a movement of dilapidation, flamboyant memories of human sacrifice, of consuming without return, a pure and simple dissipation.

‘Does your mother know? My pink little tongue – her vulva – my curtained seclusion – her accidental likeness – galvanized jerk juice…’ Oh man, this is the hard boiled style required for the hogtied material which, as she puts it in ‘Counterilluminations’, ‘… lunches on his prick at the right extremity of the terrace drifting away in cosmic dust, the old interstellar scream…’

That’s what she can do. The old interstellar scream. Right out of Ravensbruk to the future and the stars. This is writing that convulses in sublime indirect technique. Her books are slagheeps and eternal pyramids of literature. She writes drooling sanguine twilights. Has intent. Her style is for the stinking earth, the oracle that is the most violent. Her great characters are squandered by history and idealizations, formalisms, and formations. She doesn’t ask ‘to what end?’ She asks when to end. It’s as if she’s tracking an oblivion that already happened. As Mark E Smith asked long ago: ‘Who makes the Nazis?’ Szasz answers. The killed schoolgirl.

She’s looking straight out at you dear reader - and lifting her skirt asking for the spank. She confronts the mutable immobiles of current art with perpetual ruination. She overrides overemphasis on relations of interiority. What happens to the skin and what pushes past the skin inside is a matter of opening interiority to a further layer of exteriority. Her characters are physically boundless because they present the limitless abuse of destructive bodies. Her characters all have the character of someone who has been run over by a tractor or pushed through a high window. Or shot in a field above a pit they’ve had to dig themselves.

There are no events in Szasz. Why? Because everything happens. They are eternal over a succession of moments: thousands of years, a period of an hour, half an hour, five minutes, now. They constantly gain and lose molecules. They are expressive units we can hardly stand. What she’d say was that maybe they were impure events. Or pure expressions. Or propagated transformations where there is a moving project covering all of them, all her novels. They are relational. They reform themselves by coexisting as a flow. Are thus creative rather than creation.

She writes about live dead people. All motion is really at a standstill. There’s a lot of dead inert lump matter. 'This will kill that.' etc. Hugo echoes out: ‘ The Nile will kill the crocodile, the swordfish kills the whale, the book will kill the edifice.’ Hugo’s great question is: 'One can demolish a mass; how can one extirpate ubiquity?’ Szasz kind of rehearses a vague answer.She is the great archeologist of withered historic memory. The lifeless bareness is neither instantaneous nor spectacular. Reality can’t be like a distinguished piece of pastry, a Savoy cake baked in marble. Debasement can’t be a sepulcher. Not really. Books kill architecture and they kill literature when they become like the Manhatten disco. She's no disco.

She is the opposite of hypertextual, nonsequential, reader controlled link up. The best we can have is dross. Liminal landscapes of setbacks and smashed perimeters. Szasz is at the centre though, not the edge. She’s – perfect. It’s a stimdross modernism she does, ‘the Corbusian subject as the gentleman puppet on the architect’s string’, recovering a holy plane for potential futures in used landscape (stim) and unused ones(dross). Her polluted spaces replace any sense of ourselves as Poussinesque ruins.

Her strange defiled girls are metal oxides, plastic yellows, cracks surrendered to a nature of ruin by magic, obsolescence like the living dead. But these are the actual living dead. Scrap. Scrapped. Szasz asks: how do you get to be scrap? Szasz asks: how do you do being scrap? She has a way of turning it all to texture and reclaims it. In so doing Szasz is the most humane writer of morbid.

'This nineteenth-century chateau set in the Swiss countryside within convenient range of the Gstaad slopes also boasts one of the largest private collections of sadomasochistic pornography in the entire canton of Bern. Most of the items I have been invited to view consist of image after image and scene after scene of young women being completely objectified (in terms of their appearance and anatomy), verbally abused, psychologically manipulated and cruelly degraded by older men (and sometimes women) before ultimately being beaten, raped, decapitated and dismembered (although not necessarily in that order).'

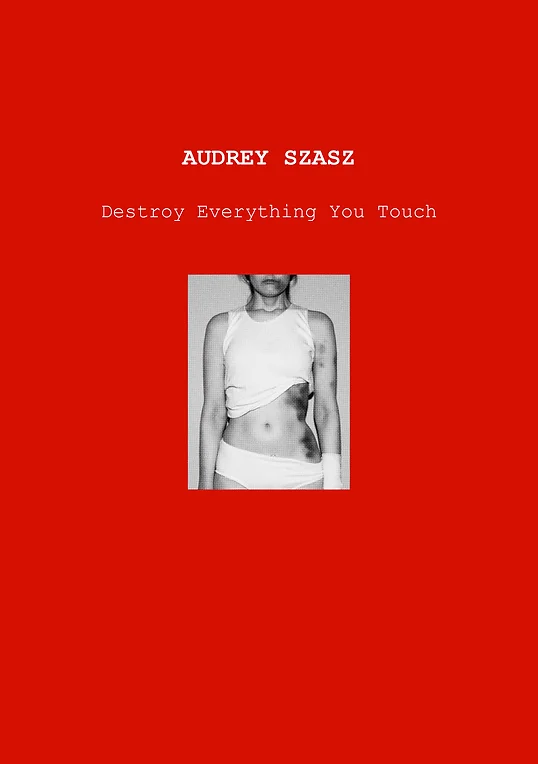

In ‘Destroy Everything You Touch’ the lush space is all rusty and defiled and has gone bad.

‘When I was thirteen years old, my grandmother told me that she had once been attacked and raped by a member of the secret police.’

The old relative continues by telling her grandchild that everything subsequent was a matter of walking towards ‘post-rapture’ where ‘we will walk slowly across the dusty soil – between the unsightly hovels and radioactive ruins, towards a collection of tall concrete huts resembling outsize sentry boxes that rise high above the arid embankment of an evaporated river – discussing the manipulation of the fabric of space-time and alterations to said continuum.’

This is discreet mannequin writing born as desolation under the sign of wonder in an electrified gantry. Her grime and stains form something inviolably truthful. The sex and violent abuse is dirt not as aberrant matter but as a constituent part of our lust material. Szasz’s writing style both accommodates the violence and perversion but also anticipates it in a way that judgment is washed off like a weathering experiment on a forgotten concrete terrace. She writes layers. Her conventional plan, section and composition builds intense alchemical pleasures. We follow these damaged dead girls like following one liquid dissolving another, like dirty rain dripping down a drain.

A character says: ‘ I cannot identify a single reason why I should feel this way… To be morbid , I feel like the version of me who pitched this project is a haunted doll who I’m propping up in the Zoom window and puppeteering …’

That’s a good way of starting to get Szasz in a glassy focus. Which is what we critics try to. ‘The thing that haunted me the most was a mask that had nothing but two holes so the victim could breathe but they couldn’t see or hear. As a consequence they could have done anything done to them and that I found very frightening.’

This is another angle. Like an endless Europe of the self, as she has it, but in the corpse fetishised dark. The girl is being starved for roughness, porosity, moisture, chemical composition and general bioreceptivity. Her girls are all beaten, tortured, manipulated, killed so they match the existing historic details. Her writing forms a kind of hyperpatina of atrocity. Engels described Ancoats, Manchester, as the last stages of inhabitableness. Szasz’s novels are too.

Szasz is Ballardian in her relentless inquisition of what history has trapped us in and the future its cancelled. Her characters have all been churned. They are laid to waste, left abandoned or in states of extreme dormancy.

‘Shut your mouth,’ Mother tells me. I shut my mouth. ‘Wipe that idiotic grin off your face,’ she says. I wipe the idiotic grin off my face. And as I emerge from diazepam slumber I realize that our train has pulled into the station. Pain, invisible, but etched within me like crystal. Welcome to London St Pancras International, where this journey terminates.’

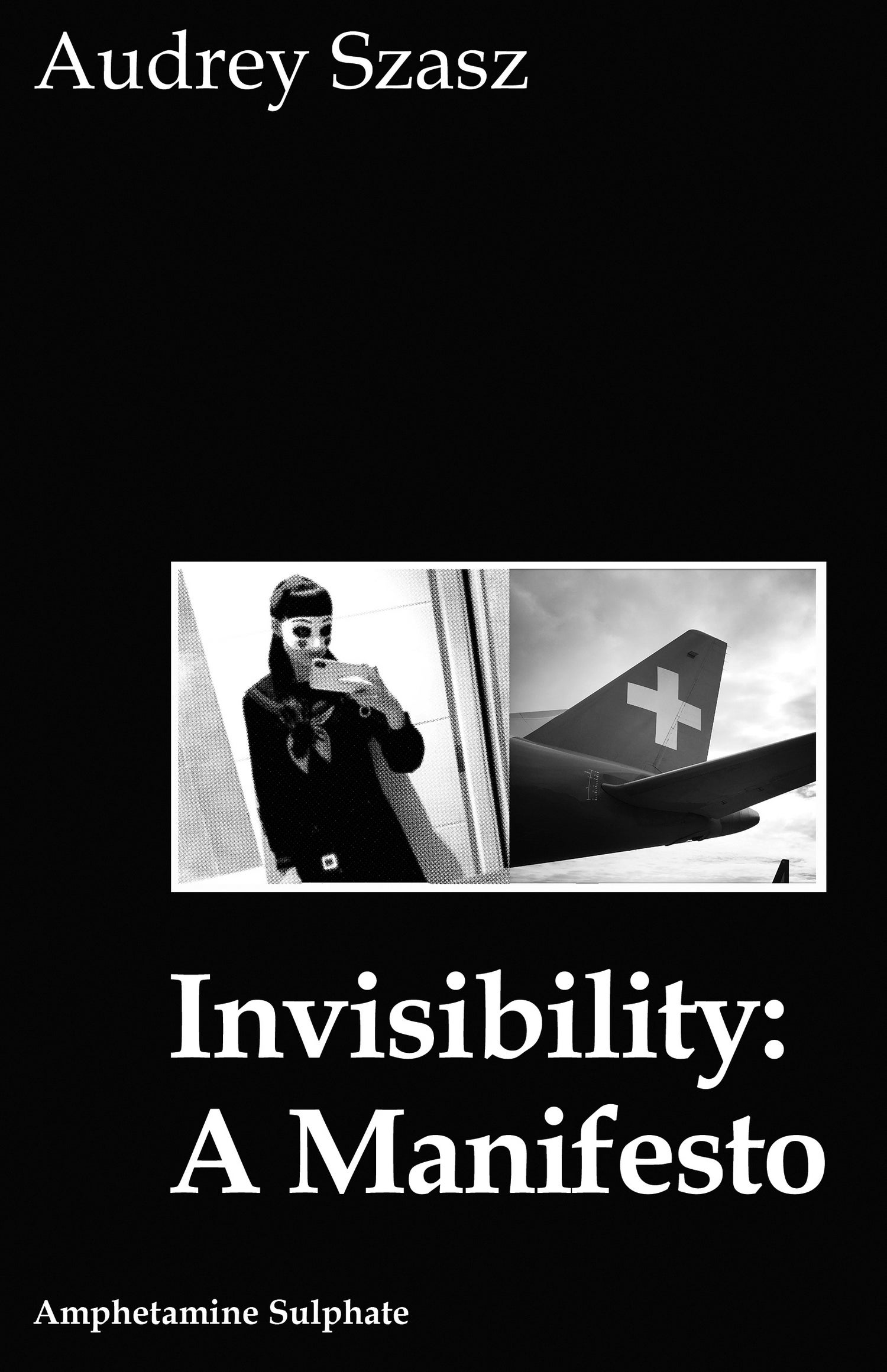

‘Invisibility: A Manifesto’ is no travelogue. It keeps its modernism all modernist by locating agency beyond the hand of the author. Szasz turns up in this circulation of stories involving Danuser the out of control psychopath who at one point ‘… burned her clothes and, after mocking the corpse, partially dismembered it and ate the soft tissues.’ This is a short novella with a slow architecture. Everything is forseen and nothing is an imaginary alternative. She has a style that refuses to circulate. There is no way this will ever be given over to obsolescence. She has written an implosive violence, a fetishised bolt of culture which is itself fetishised, to paraphrase Baudrillard, as the literary involution of inertia.

In this way we can see her link to Ballard and de Sade, where crisp precision is given to the container like teaching units of desolate psychology, live units and life-span sociopathology. It's a carcass of flux. Here’s the big clue: ‘Sometimes dreams do come true.’ It’s how that particular book ends.

What dreams? The Nazi and Soviet regimes in the middle of twentieth century murdered fourteen million people in what Timothy Snyder calls the Bloodlands. From central Poland to western Russia, including Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic States nearly all the Jews plus Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, Russians and Balts were murdered in twelve years, between 1933 and 1945. None of these fourteen million were soldiers. Most were women and children and the elderly. Most Jews died over pits and ditches. Most died near where they lived: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Soviet Ukraine, Soviet Belarus. Germans sent Jews to Auschwitz from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, France, Netherlands, Greece, Belgium, Yuguslavia, Italy and Norway. German Jews were sent to Lodz, Kaunas, Minsk, Warsaw to be shot or gassed. Death factories were used in Treblinka, Chelmno, Sobibor, Belzec. Mass murder of German Jews happened in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, not in Germany.

Hitler dreamed of killing more than he did. He planned to destroy Poland and the Soviet Union, exterminate their ruling classes, kill tens of millions of Slavs ( Russians, Ukraninians, Belarusians, Poles). He planned a starvation plan that would have murdered thirty million civilians. Stalin had starved millions of Soviet citizens in the years of peace before the conflict with the Nazis. He murdered three million starving peasants in 1933. Hundreds of thousands of peasants and workers were killed in the Soviet Terror of 1937 and 1938.

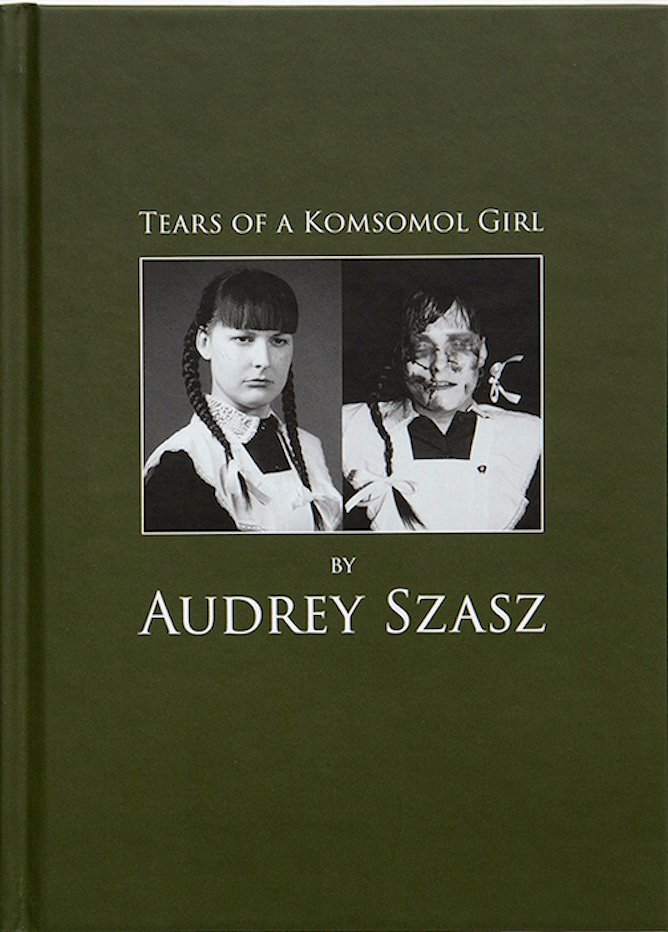

Szasz’s girls come from this. ‘Tears of a Komsomol Girl’ ostensibly happens as the Soviets dissolve.

'Tears of a Komsomol Girl is an experimental concept novel based on the real-life crimes of Soviet serial killer Andrei Chikatilo, who was finally executed in 1994 having been convicted of murdering 52 people between 1978 and 1990.USSR, Rostov, 1980s. Arina, a young girl — insolent, obnoxious, but most importantly musically gifted, poses as the ideal student — upstanding, hardworking, and a member of Komsomol — the Soviet Union’s Communist Youth League. Fantasising unrealistically about becoming an internationally famous classical violinist, and yet simultaneously behaving as cynically and hypocritically as she can, Arina uses her Komsomol duties as a pretext for strutting unsupervised around town of an evening, fraternising with soldiers and Party bureaucrats alike, compulsively lying to cover her tracks. And yet her sleep is punctuated by obsessive and oppressive dreams concerning a certain killer who’s been on the loose for years — a ruthless, sadistic and thoroughly vicious opportunist referred to in rumours as Citizen X, the Rostov Ripper, or simply Satan — a monster who brutally slays children and adolescents having assaulted them at knifepoint. As the killings become ever more tortuous and frenzied, and the number of innocent victims tragically swells, it’s only a matter of time before Arina finally crosses paths with Satan, and her nightmares turn into a reality.'

‘A sadist called love. Everyone hates a party activist and nobody likes a suckass. Today there’s soap in the stores. A haggard drunk slumps to a stupor beneath a clump of tall poplar trees. A car sinks drearily into a river of rusting flames. There are mould spores in the air, the walls are wet with damp, the lightbulb in the stairwell’s been smashed again. It’s murder keeping paradise clean. An elderly man, his ancient overalls covered in dust, sweeps the streets with a splintered broom, his spine crooked, his entire frame hunched over , as if to curl inwards like the dead leaves he brushes from the pavement. Future? What’s all this about a future? I have absolutely no idea what you are talking about.’

It’s spare, brilliant writing, glowing in that light whipped despair of a sensibility razed years ago, before it was even alive, razed to the scorched earth of the Bloodlands Sodom and Murder orgasm frenzies. Death hangs about throughout. There’s a psychopath who kills the protagonist again and again in brutal gusts of deranged violence. There’s a kind of lightness to the dark holes in her eyewitnesses. It’s an introverted expansiveness she’s handling. She can’t take her eyes off the strange eeriness of a holocaust world. The dark bloody soil is in everything. Szasz refuses the forgetfulness of refinement. She writes like an angel looking to be sodomised and lashed by a rusted claw handle. What strikes the reader is the vicious murderous mosaics. The ravager is always, always present.

The girl’s voice is disturbing, disturbed, refusing any Utopian proposals, ruined and yet in play, dried into emaciated interstitial images and events. It’s a productive emptiness. Her style and material challenge any easy binary opposition between formed and deformed. Arata Isozaki says that professing faith in ruins is equal to planning the future. Has Szasz faith like that in her ruins? Have her ruins?

‘Future? What’s all this about the future? I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about’ says one of her protagonists. This is more the last stage before disappearance. Every time it’s that.

‘ I didn’t get very far. A scuffle ensued. It was all a chaotic blur of limbs and hot breath and fabric and fists. I don’t think I even managed to let out a scream before I was repeatedly punched in the head. Nobody had ever hit me like that before. I almost flew across the room, collapsing in a tangled heap. I was stunned, tasting blood, almost knocked unconscious. As my senses reeled , I realized through my dazed anguish that the chair was lying on its side again. I myself ended up pinned on the floor with my elbow twisted painfully behind my back, my skirt was in disarray, exposing my backside, and the man was kneeling on my thigh, gripping my wrist. …’

And on it goes. Szasz’s languorous prose underspills and terminates always, always, in the twisty perverse detail, the tell. That cunning ‘exposing my backside’ plays the role of the aesthetic deformity that brings to life everything. It's an aberrant beauty, an ugly effect of fetish greed and grime ugly reality done as pervert desire code. The eloquence is a detonation in the far lizard cortex. There’s nothing but the long-time truth here, but greasy and smooth and squalid and hatched out. This is writing that ruptures its own surfaces. We’re exposed to the moisture of all the faults that run out like spalling, rust, cancer, time bomb legibility. It’s a Viennese imagination, like a late character writing after Musil. Maybe Szasz is Agathe in The Man Without Qualities or bad girl Rhea in Plan For the Abduction of JG Ballard.

What’s wrong with much modern literature? It avoids the historic pollution. Cold war narratives are spy thrillers – Le Carrie’s public school dramas or Len Deighton’s class warriors, say. Or they spread into admixtures of irrelevant genre fantasy style like Bond, Mission Impossible, or cleansed colonial myth. They’re often men writing. Szasz’s are unique daydreams about the historic fetish violence secreted by murderous rapemen told by girl receptors imagined as cadaver futures. Her tropes are rape, S & M, torture, murder, domination and submission routines written out of history in girl skulls, brains, bodies, genome strands of nightmare embryos. Everything is bad weather coming through inexpensive skylights.

Her voices are the voices of cold sprayed death and horror run amok in a certain, particular proliferation of ways. They’re like protocells which are cells not quite being cells. Anymore. Szasz writes to a very immense deathliness of life, a sense of abject fertility. These are girls who work because they have to accord to more primitive treatments than others. Szasz creates wet systems with primitive mental glands. The killing world stimulates simple chemical exchanges, tracing responses from the surrounding atmospheres. The emotions are synthetic earth, hybrid soil. The girls are new living systems. They are the future midwifed into existence by extreme violence, sexual replicants and innovative trauma routines. The continual shocks that emerge from Szasz’s prose running from the lack of ambiguity regarding these ‘not-quite being girls’ girls. They are clearly competing with the non-traumatised existing life systems as a lost viable alternative. They can self replicate and evolve. They can be transferred. Endlessly.

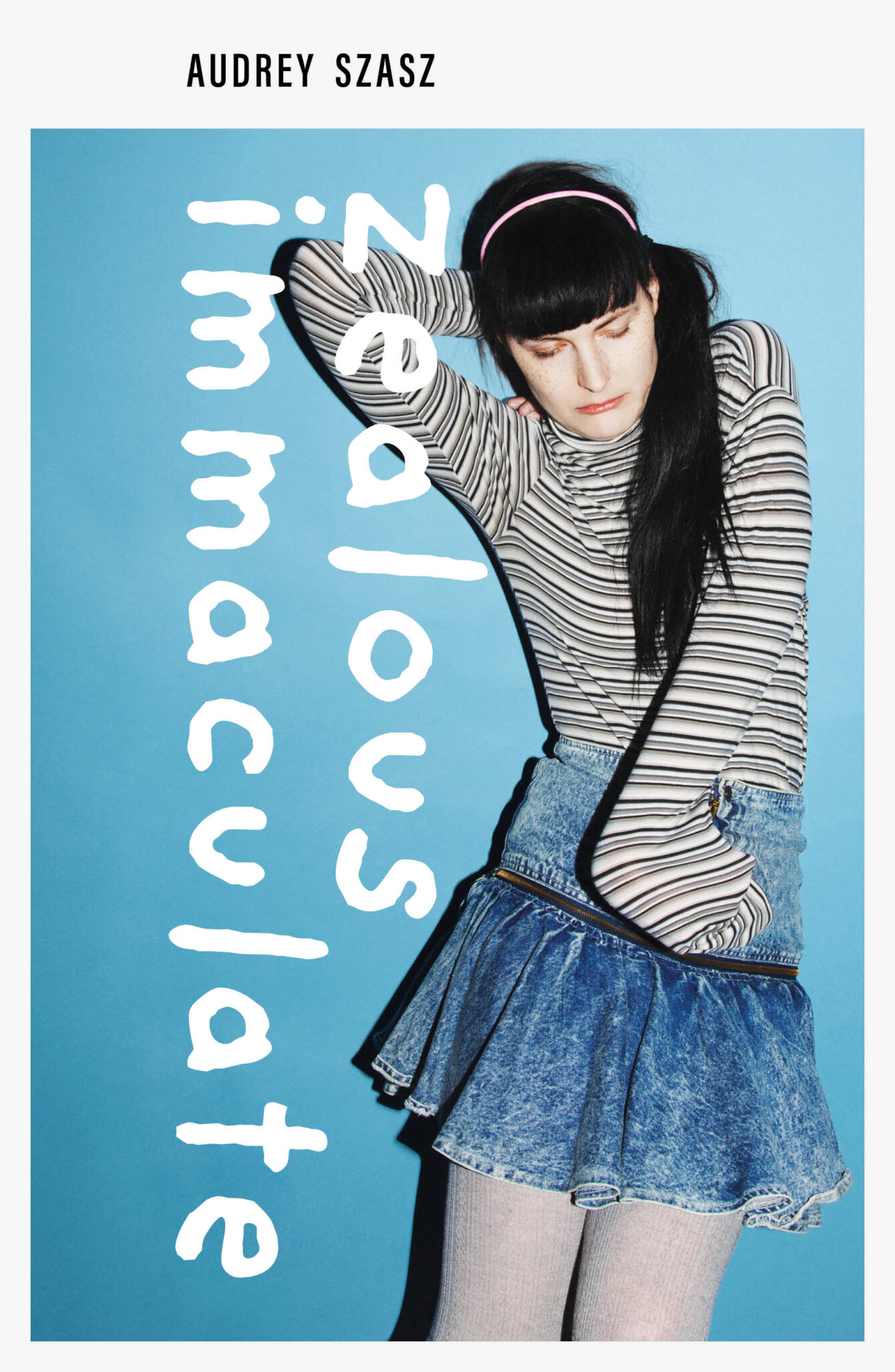

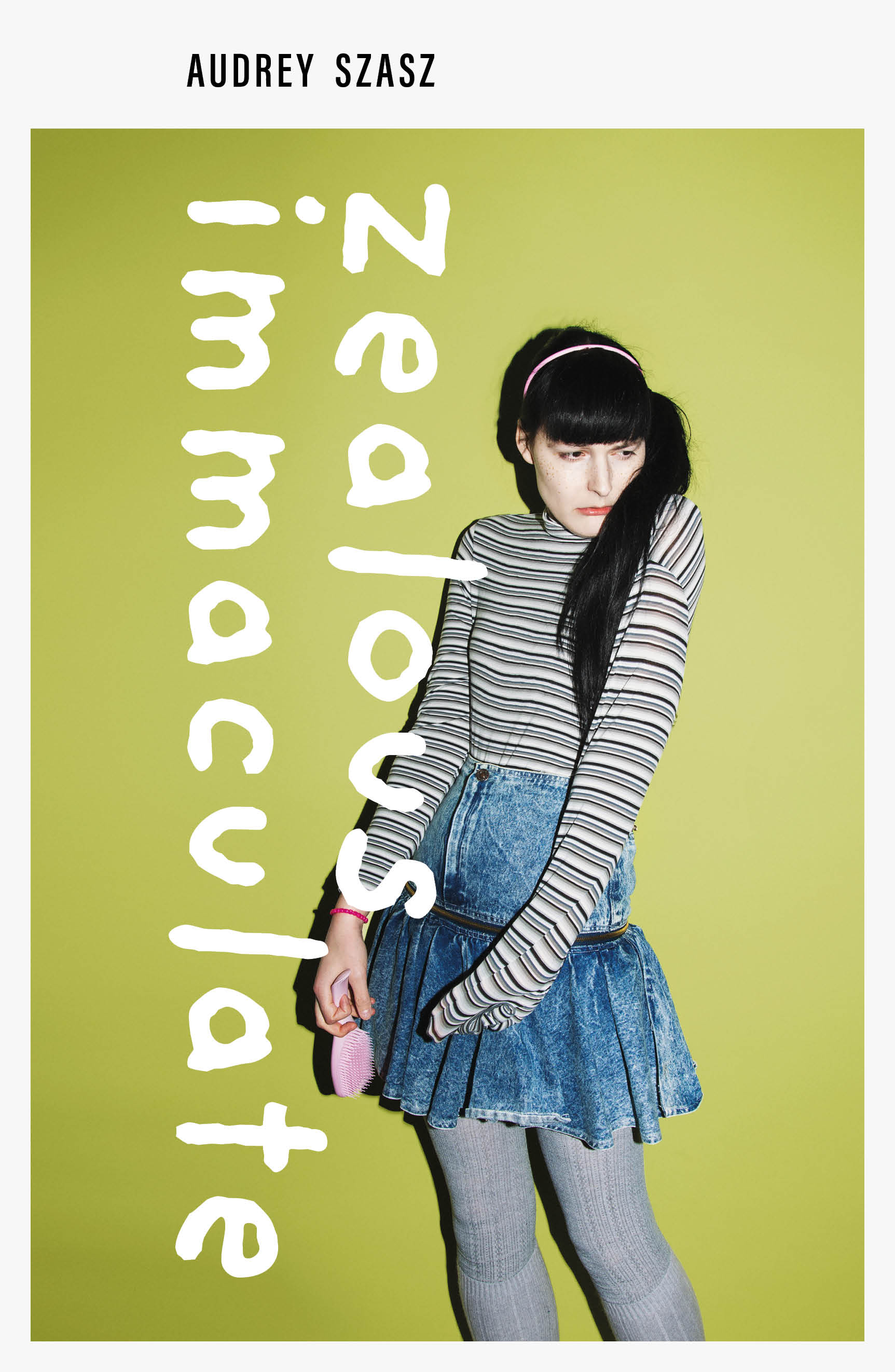

‘Zealous Immaculate’ winds this new species of life through the convolutions of an orphanage.

'“Basking like a reptile in your reflected glories. I just respond. Sometimes I don’t even do that. I just do whatever I end up doing. No thought. No plan. No real motive. No overarching theories or philosophies. I can’t even stick to a routine. I lack discipline. Can you give it to me? Can you tell me what to do? Can you force me to do whatever is necessary to survive? From one day to the next, until the very end? Will you give me the beating I deserve?'

The environment, with the exact totalitarian elements of the previous novels, creates the exact same voice parasitical upon the unlimited perversions. The beings are infilled by violence and reordered sexuality. This is a perfectly rendered novel, and a perfectly rendered version of the previous and later ones. Each time she does this she’s being original of course. Szasz is continually going back to the ruin. Each experiences its own. She writes directly and materially with the intricacies of deterioration, demolition and termination of souls as a kind of frenzied undertow.

'I wish the nurse would tie me up so tightly my blood circulation is cut off and then smash a vase over my head and suffocate me with duct tape and a pillow filled with Canadian goose feathers. I wish a mortar shell would land on this building. I wish for air force drones to bomb this town repeatedly for days on end until there is nothing left except a vast lifeless wasteland. A cratered moonscape. I wish for walls of fire to consume this yokel country. I wish a phalanx of marauding cyborgs would stroll through the towns and villages executing any living creature their sensors detect. I hate everyone but I hate myself most of all. I vouch for no one.'

Is this science fiction? Probably any truthful novel has to be now. Emotions are nerve futures working terror rictus breakdowns across the whole span of body cortex impulse codes. This is all a fractal body. Across the books as well as within themselves. Szasz herself writes as if she is looking to find the toxic verb points of angel plasma. In other words, her embryos are crucified torture brain algorithms. Her central characters are exoskeleton’s of all negative emotions made sublime and desired. They devour their grief and pain and are sumptuously deranged. Its as if she’s compressed the whole of the global death marches, camps, murders and terrors into a sickly period of cock spurting cloned assassin men. This is known by every girl on the planet.

‘What is guilt anyway? It’s arguably not a question you should find yourself asking – well, at least not this often – I want to accelerate myself to the speed of light and travel to the nearest star – it takes fifty thousand years to travel only four light years – imagine the privilege, as a race, of being able to pollute and ultimately to destroy the ecosystems of faraway planets – there are opportunities all over the galaxy, if you’re willing to look for them – but I’m not talking of floating in a tin-can around a blue orb – I’m talking of future-shock levels of a technology not yet invented or discovered – memories – you are a distant sun, blazing – a searing and scorching light – through space and time – we’re all allegedly mortal , but in a single moment, we inhabit the infinity of a stolen kiss, a nanosecond in the ocean of temporality …’

This is a parasite brain jointed to hydromaniac levels of mystic chemical anthropoid junk. Szasz startles us constantly with these searing perplexing moments where the register shifts dramatically to a sort of sutured defiance. A type of reptilian limbus intervenes, the nightmares of cyber nature disclosing the bleak banal surroundings inhabited by these strange creatures. Their acceptance is the real derangement. They move from the banal defeatism of a raped dom slave to hyperlinks of adrenelin chaos murder circuits that reach out from the orgasmic past into endless futures of suns loaded with sutures of fear crisis lunar coils and gene war apps.

Szasz writes like you imagine a cut vein might be read. Her landscapes and inscapes are equally done as simulacrum voids. Defleshed crash sites. The retro devices of cold war oneiric scripts. It’s where her girl says ‘I hardly even know what I think or feel – the self seems inconstant, arbitrary, absurd, redundant – I am rotting away in my flesh…’ Someone, as ever, has done a job on her. And as ever, she’s installing herself inside the violence like she’s become an android or something. Here’s one of many of Szasz’s discoveries: the new human is a desire-protocol creature working as a parasite device for defleshed controllers. It’s like a long, long cadaver rapture.

When she co-wrote that Ballard inflected sequence with the immeasurable Jeremy Reed which I mentioned just a moment ago, it was at once unavoidably obvious that her Ballard meme was sutured to a hologram and butchered up, embodied and definitely female in its entrails. Reed’s was a brilliant imitation of the Ballard techno futurist metallic inscape (reminding me of Stephen Barber’s incandescent degradation spasm anime porn trilogy Tokyo Sodom ,Tokyo Slaughterhouse and Tokyo Supernova ) but Szasz channels a different charnel house. Her entrails are female. Her cortex is attached the female cadavers of the history that fecundates the living body of literature and art that tries to glue things together. It's a writing that reverses the after-images we’ve maybe grown too cosy with. The spectral pheromone of a girl who is a body with swastika logic psychosexual excoriation routines applied inwardly should be perversion through and through. So Szasz inclines.

Her girls are the pale meniscus of unspoken, unspeakable histories. Her writing is the shock absorber interface tuned to orgone control, sex mania, rape pheromones, hyperreal parasite scarring. These are the silences of girls conducting their own autopsies. The derangements are fluid mechanisms working to assassinate the blank spaces where what really happens, what really gets felt, what actual silver deathshead was actually the angel hovering over worldly desires is uttered and made clear as day. Her blank tone can rise in spectral guerrilla humour and replicated mania, and that keeps it lively. That’s what makes the writing like sex anthropoids excavated out of the deathcamps of less than a century ago. There’s the vertigo of a strong beatdown and a squalid vim in all this.

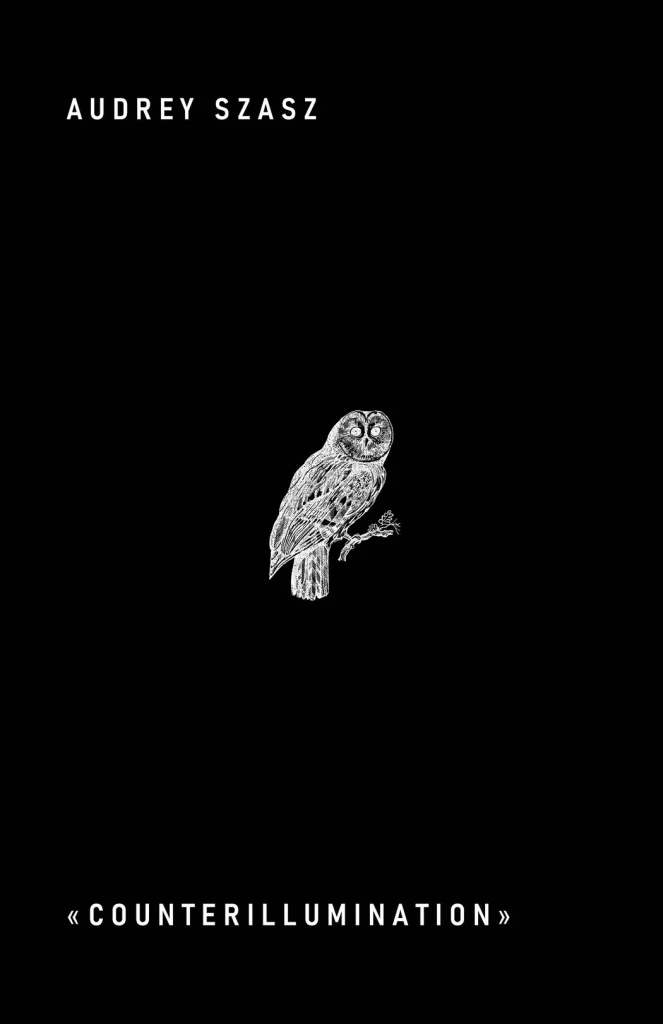

The masterpiece is ‘Counterillumination’ if only because its play with history, time, fetish porn, the Nazis and malicious kink is done as a perfect cosmetic of perverse order. This is order as alienation from life and the death of matter as we know it. It reorders. It eliminates the shadows. How do you abolish the shadows? Arbitrary political acts, monarchical caprice, religious superstition, tyrannical plots, epidemics and illusions of ignorance. This is a beautiful example of partitioning art where waste becomes nature generally, finally. Everything outside the economy of human value is taken inside. Social ignominy and the cadaverous degradation of torture become divine in unlimited, unshackled regimes of ecstatic torment and pleasure. This orgiastic nightmare of torture death camp agony excludes everything but lucidity.

‘Roll call started early in the morning and was repeated several times during the day. We were beaten for all possible and impossible reasons. If a young woman called Grese came along we had to stay on our knees in the dirt, sometimes even for eight hours at a time, holding heavy stones above our heads. During the selections Irma Grese, together with her colleague Margot Drechsler and the psychopathic SS Doctor Mengele, decided between life and death. The naked women were forced to parade in front of Mengele with arms raised ; and then in front of Grese and Grechsler. Mengele made the first selections, while the women might – out of sheer spite – select people whom Mengele had initially disregarded…’

This novel excavates what official histories either look away from or euphemize. The rape routines and death games, the torture hydromanias, the drug attack android desire protocols, the bondage murders enabled by the totalitarian routine pleasure/torture sites are its grave gravid materials. History as orgone death flux is rendered in the subversive chat of almost comic gossip routines spliced with sex/rape/murder perversion raptures. The grubby dark is shown as an enclosed evil. All oneiric focus is on cadaver fluidity and narcotic power technology. The sick death games are handled within cool brain universes of a bored sort of perpetual porn imaginings and disgust fatigue. Szasz writes into a nightmare and gravitates towards the submerged materials with a kind of black glitter in the prose. It remains vital and always luminous.

She has a way of making certain the reader can’t avoid the materials’ nudity. If you do try and avert your eyes the only door she keeps open is a double looped fetish imagining that corrodes and erases itself as we go further and further into the insane logic of the carnal derangements of mass murder and mass psychosis. It’s the best novel about the concentration camps, about the Nazis, about the refrigerated entrails of recent history that I’ve read. It’s as powerful a fictional response to that history and our contemporary future space as anyone's going to render. I recently read Len Deighton’s ‘Winter’ which in a sense covers the same period and is a masterful book. Yet Szasz’s is the luminous memorial. She holds her nerve – she’s supremely nerveless throughout all her writing – and so reaches those criminalized places of semen/gelid ejaculation that rots and make strange everything she touches. And everyone else refuses to approach.

Her books are murder maps on an interplanetary scale. They are sex second gore files. Her horizon is as profound and serious as any contemporary writer I can think of. The entropy of her trauma distortions is pure and reactivates the history of the future planets. At the end she juxtaposes Irma Grese’s version of her hanging with the sub dom S & M routine that runs throughout the book like a subversive lucid dream.

‘Which is worse? The clamps or the cane?.... Bend Over’…

It’s a vital excavation of the hyperreal mutational nature and mobile violence that is our new psychosexual ecstatic life form. It’s literature that is covered in blood pleasures and sadistic nutrients. If you want to understand anything about now then this is an essential book. (You want to know what’s happening in Ukraine? It’s all here, the whole Putin snuff movie fantasy scanned as dog oneiric entropy! Whew!)

Szasz’s oeuvre is a vital serum. She has synchronized the memory joints with vaginal screams and laconic futurist embryo scripts. Her characters are the new beings retro accelerating violence to a pristine nerve from intergalactic sado/masochistic Nazi/Stalin planet reverbs. This is genius.