Brief Aside on Vilde Bjerke Torset's Apollinaire and Other Horses

By Richard Marshall

Vilde Bjerke Torset: Apollinaire and Other Horses (If a Leaf Falls Press 2022)

What do you want from poetry these days? Simulation, imitation, possession & metamorphosis would be enough to be going on with if you ask me. And deadly carrots, dragon bites, the fiction of the imaginary vessel, of doubles and whosoever doesn't hang. (Let’s be clear, not psychopathological, parapsychological mumbo jumbo but rather Paul Valery’s quotidian, ceaseless insidiousness.)

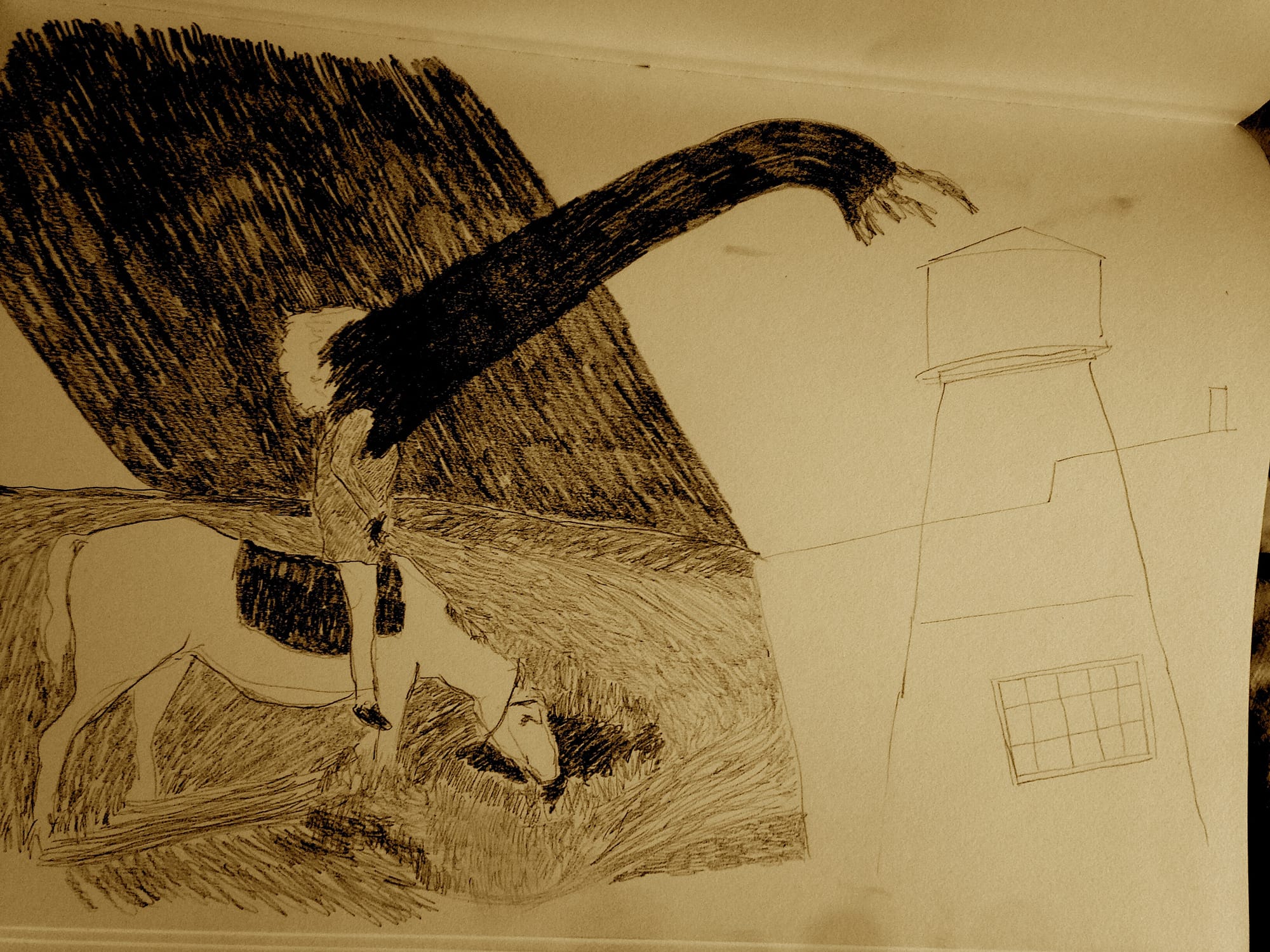

Torset is a poet caught in the act. In this sequence of miniaturist works she divides and simulates, and begins by offering both the certainty and uncertainty of objects … ‘ a cow is something like a horse…’ with the prosthesis of a drawing as if to prove the first poems’ fathomable gap: ‘ it just doesn’t look right.’ Packed into this tight little event is the promise of a system, a palpable medium ( she’s all paper, ink, pencil and each one of those, as she draws and draws our attention to them, extends our realization of what prosthesis might be) that leaves the reader immediately exhilarated by the promise of a project whose fortunes might end up looking neither right nor upright, but yet nevertheless remains one calculated to be an outlined apparatus for a poetry that both invites and then refuses the mind, exploits and discharge of the reader, and which in a cosmic sprezzatura sews humans and horses back together. It’s just like when Hercules captured Diomedes’s mare despite him knowing too much theology not to be aware of the trap. We’re in a trap but that’s the point of reading poems: we become the residue that in the end is burned. So what do I want from my poets? I want them to do that to me.

The horse is the crucial animal in the collection, and Apollinaire one that implies the whole of modernist poetic discourse and also the echo of the Psalmist when she sings: ‘ You shall save men and beasts , O Lord.’ Not that this is a religious sensibility at work here, yet the generosity of the poems works as a kind of strange reverence. Torset destabilizes the controlled images of beasts. She is as tenacious as those who would keep humans and animals separate. ‘Apollinaire is a horse (I)’ designates a genealogy that binds horse to human in a stark, domestic chain. The simplicity is a trap. A poem is a regime contrary to everything around it. It helps us see what we didn’t see before. A reader then dwells with reverence, gratitude, and a sense of utility. There’s always a sense of the obscurity deepening as we read Torset, which is always where ‘the shadow is gone…’ and where the reading eye ‘is all well and good/ but says eye/don’t think long term fix this…’

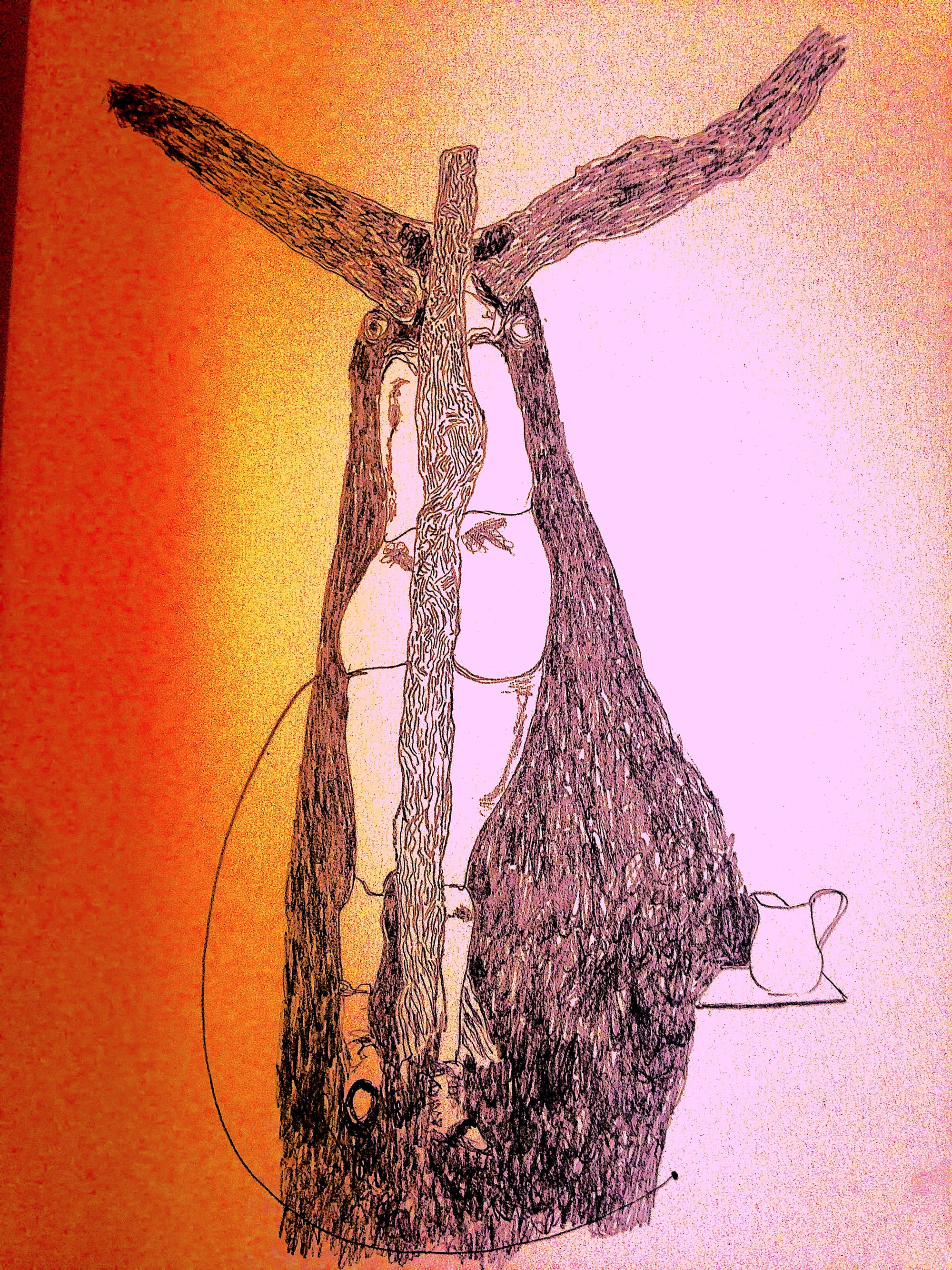

The whole collection is an enormous, powerful machine but rendered through miniaturized components – small lists, diagrams, drawings, letters, retorts, dialogues, summaries, spare detonating phrasings (eg ‘the windsucking beauty…’), paradox, pledge reassemblies, historic fragmentation and more – but for me there’s a single repeating question which is - when is a horse a horse and when isn’t it? Which might be two questions. Bite me. It’s the defining riddle of the collection. Answers come and go: when it’s a cow – but that really really doesn’t look right; when its bloodstock – but that seems , well, too bloody, too harsh, too sacrificial and thus going in the wrong direction; but also when it’s a poet’s voice, maybe an irish poet to boot – and that seems better, and to quiet the blood; and then comes - when it’s spirit...

When it’s spirit is the answer that gives us the Stallion of the Cimarron which combines the impossible living autopsy diagrammatical image of the horse both as a streaming runner and also as a version of Gradgrind’s naming of parts. This helps capture in a glimpse how Torset organizes her derangements. We get the advantages of the lively and wiggling humour crossing over with the dark, sinewy knower of everything – a bit like chemistry and physics when they were content enough to be alchemy. She has the nerve to draw on a Dreamworks animation about Spirit, a Kiger Mustang stallion and works at the contrast between James Baxter’s animated hand made drawings for the film and the ancient anatomical diagram to present a profound and uncanny destabilizing moment which points to something divine – and by divine I simply mean just – that both Baxter’s drawings and the anatomical illustration both cannot grasp alone.

So when is a horse a horse?- well, here the eye is being asked to sort this and Torset’s machinery makes clear that just looking, and that includes reading, isn’t going to get us the answer. Does she have instructions for what we need to do? Well again, this is beautifully designed machinery and so of course she offers us help – but not necessarily to get an answer in any straightforward way. Each poem, nevertheless, gives us what we need. They are hatchings at night, they are ‘featherlight scenes of displacement’, they are ‘somewhat similar to the mounting process, but in reverse.’ I think this is the way to read them. I keep in mind what the issue might first strike us as being: the seemingly elusive nature of nature, the essence of horse, of the individual horse too. This might be philosophical but poetry’s not philosophy. Poems have other fields of sense and it’s a mistake to confuse them with non-poetic ones. Torset knows her poems are best seen as ‘holding breath before impact,’ and indeed as I read the collection it was as if I was been given a way to divine a poetic disquisition of ‘high dream’ and rude romanticism – but post modernity and post post that too.

The poet is playful so when she writes, in ‘to Jubilee & Lis’ ; ‘they are counting the victorious/display: somewhat similar to the play process, but in reverse’, she is pointing to the fact that playing at playing, even when done in reverse, is still play – unless it is merely something ‘similar’. So it all comes to that similarity, and its nature. After all, as she started out with, a cow is similar to a horse in many respects, but is nevertheless not a horse even though we might wonder whether it would be going too far to say that a cow is a play horse in reverse? Well it's maybe a little too far. But only maybe.

Here’s a contrast – I alluded to it earlier. Understanding could be to stand and watch the creature in its habitat and guess the source of the beauties: or lie out the dead meat on the autopsy table and dissect it and name the parts. As Wordsworth reminds us: ‘we murder to dissect.’ I have a suspicion that there’s this contrast working through here. ‘How knows how?/how knows to be a dragon?/ how does the body?/ how does the mind?’ she ends ‘Velegro’s last dance, and it's a profoundly moving moment, supremely mysterious and enhanced by its delicate framing and tone. Each moment acts like a bulwark against the impure and unjust. They work as if ordering a divine seal, by which I mean that purely utilitarian, purely definitional categorizations will be locked out. So long as we read aright we’ll be too. And grasp the divine guilt in existence that can’t see a horse (and thus existence) as a horse, nor this particular horse as this particular horse. Well, that’s a pretty heavy mead. And when I asked what we were wanting from poetry these days, well, this for me is what I’m wanting. A poetry that orders in poetry (not as thoughts, ideas, proclamations, understandings, morals, philosophy, science, religion or any other guff) the immense disorders, the comparisons with beginnings and endings, the consolations of things bigger than us, that came before, that will be after, the appearance of unease that comes when lovers stretch out on the bed, the shapeless silences, the gods and mortals, the settled immobility, the currents that flow ceaselessly, the moments of paradise and those of Hades, the infinite and discrete, the time when all in the end is burned.

Her poems offer a way of finding compassion for suffering , a silence over dying, and immense joy in the witnessing of life too, and of naming, and the many legacies of both – that is, of dying and living. ‘a horse is a horse/they are not the same/one is real…’ she writes in ‘Phoenix (not the bird)’. The best hope is to catch a glimpse of the target in mid flight. This is an old trope – I first came across it in von Kleist I think – and this idea of the irreplaceable, unrepeatable insight is also likened elsewhere to the hunter’s moment where, for example, Dionysus is of a sudden both a bull and a killer of a bull, and of a sudden the bear hunter is also the bear. The point of these sudden glimpsed epiphanies – and they run through all the ancient myths – is to refuse to separate the hunter from the hunted just as Torset imagines the poet as imagining being a poet, just as she might put it as: ‘ A poet is a poet/they are not the same/one is real.’

And what swivels round throughout this is ‘the Jim Key pledge’ – ie “I promise always to be kind to animals and other sentient beings.’ which is no easy platitude because it overhangs a fabulous line such as; ‘hooves doing jazzhands’ and is ostensibly about ‘the most intelligent horse who ever lived.’ You have to laugh – and throughout there’s a wonderful zany humour running along as if Groucho Marx was keeping tabs of each curious, weird and wonderful inversion. These are puzzles that really do keep you wondering whether you’re reading them the right way round, as if cause and effect have become jumbled up. The lines don’t walk along steadily but are like hyenas, with back legs seemingly too small compared to the front ones. And that Jim Key Pledge calls for an atonement even before the crimes have been committed. Which in turn of course raises the issue of what crimes in particular are we talking about here. My guess: I think these are the crimes committed on the inside. Animals – even the most intelligent horse – is never a guaranteed solution but more like a continual trial. Trials are puzzles with sacrifice attached. And knowing who is in the dock is surely a key element to being kind, and if there’s one thing that happens again and again is that we need a stable name ie one that is firm and grips fast.

And yet Torset, inventively playful as she always is, makes this a site of both stability and its opposite. Apollinaire, for instance, has not one but ‘a couple of stable names, Apples and Polly…’ and with that we’re in the realm of clown laughter, ritual symmetries and a kind of mayhem. If Torset’s mayhem is gentle, and we are being asked to compress units of intense derangements through a child’s eye prism of play and imitation, never doubt that it’s nevertheless mayhem. This is the sort of visionary stuff that supposes no more than what can be seen when sitting down – or when nine years old. But sometimes a child can be Lizzie Borden or Lolita.

But the poem’s are too good to leave us with any simply achieved understanding, no matter how good natured. Because Torset means it when she says things are got by snagging them backwards, and that there’s a point to ‘wanting to but not wanting to talk’. All of which points to remoter scenes that she won’t speak of but will rather leave unfathomed instead. So she might be going back to the beginnings of when ‘a horse is a horse’ but she can also allude to the horse of which it can be said that ‘when the horse was a horse/it didn’t know it was a horse’, which is a different though related issue I guess. This comes with Shadowfax, Blanco and secret compulsory magic gestures out of Lord of the Rings. If this section of the sequence seems placid and subtle it soon darkens as if sunsetting over bleak carnage. There’s the predatory chill as we’re confronting the ‘slaughterhouse’ with ‘honey words and couch carrots’ – a singular trail of details leading to the last running aside: ‘there’s more to this/but how to say anything about kindness/that is not repulsive in comparison/I don’t know’.

It’s a sensibility that is travelling great distances and confronting enormous violence with the deft and infiltrating compassion of incubating nuance. Torset holds back a huge and unwritten gothic in this. What is stressed in her writing is literally the stress of all this. Torset imagines her horses as beings resembling us though different. And then wonders about the relationship and its effects. She is making discoveries out of tedious delays, mental outlooks, final stages, sedentary lives, domestication, wild animals and geometrical forms rewritten as crossword puzzles (but ‘untethered’, ‘bankrupt’ even). She can’t be sure why her events and forms happen – just as she can’t be sure of how her horses do, or anyone of us. Or things. Which is of course the point of the poetry which at first glance might look harmless but on a second look makes out abstracts that merge into each other and a bigger, more monstrous thing comes rising upto the surface. If a unique quality is seen its probably here in the hewn unscathed release of this bigger unified thing escaping from the fractions and composites, all done in the blink of an eye.

So this is another way of understanding the poems. They work as houses and middens and pens for poetic creatures that include everything that matters: hearths, cemeteries, sanctuaries, storehouses, workshops and dorms. For its the kindness that is required, and the right way of seeing horses and ourselves in that way is what is being realized in the areas of each piece assembled by Torset . Horses are everywhere, ridden or placed close. Human and in plaster. Caught up in history and newspaper reports. In double entry. In standards and dimensions. What Torset insists is that poetry – and her poems of horses – cannot always have involvement on earth, that they are sometimes no more than the pallid specters which continue to live outside the light. Poems of this nature, of this force, are not beginnings but much more like something closing up, nearing the end. They are roaming shadows, bodiless voices. This is why her insistence on naming the names, lighting up the earth and its lightness – the conversations, anecdotes, gossip – the weightlessness that expands from disregarding nature, misunderstanding or obscuring what it is for a horse to be a horse and to not be a horse, is non-negotiable.

Hence for me her Beckettian moment is then a result of all the immense pressures arising from the sequence, and its apotheosis in ‘Copenhagen, Marengo, and the Carrot’ (which I reproduce in full below) is a remarkable attempt to punch through to the other side of our banal web of intrigues, our life without insides (and hence life without outsides too). The final form can only point through from spoken words exchanged. Henry James wrote whilst in Torquay of the outline of ‘the tiny little germ of a tiny little tale’ and an old woman’s sense that ‘… with all she had outlived , nothing could now happen …’ He adds: ‘… One wonders, but one really doesn’t really want to know – what one is really interested in in guarding and protecting these simple joys. One watches and sympathises, one is amused an touched, one likes to think the old party is safe for the rest of time.’ But James knows that it’s by bypassing the animal in us that we reach that sense of triviality. Well Torset isn’t an ‘old party’ but she is a poet and poets can’t but be transposed into any part that fits. To answer James she distances herself by becoming closer to her animals. It is as if she is inverting the Jamesian perspective which seeks protection from nature and animals rather than finding oneself implicated.

So in ‘Copenhagen, Marengo, and the Carrot’ we are unbearably most human and most horse. We are displayed (or misunderstood ) as ‘Two outlines meeting over a Carrot’.

‘Marengo:

how’s the carrot?

Copenhagen:

It’s a carrot

Marengo:

So much the better.’

Well, after this, what could possibly happen now? This is the vortex of what remains unsaid and the interstices of other stories – Beckett’s obviously, but so too Stevenson’s and Turgenev’s and Gogol’s to set the ball rolling – where what corrodes any hope of solitary calm is its ritual nature, the quiver of tones shifting, the menace and fatality whereby anything might turn and turn up. What is there in this but the notion of a horrid danger ready to emerge. A sense of waiting that is like writing because it sees everything. In these few strokes Torset leaves her horses in full view whilst vanishing them and leaving others in possession. And sure, we'll soon be where ‘the name of the horse isn’t known.’

The exterminating angel is what a poet has to be at some level. She has to express the events happening at the other side of the square, so to speak. She has to understand that her horses are not just doubled, they are doubles and indeed, finally, irreversibly, rivals. Thus the poems become like the torturer struck by a fit of benevolence. It is wholly unbefitting and yet where goodness intervenes. And so as we run through these many horses, and they keep returning as if the one redone, redoubled, reupholstered even. This is Torset’s strength: she is quite in tune with the violence of her imitations and keeps herself alive to the primordeal venture whereby she sinks her voice into the imitation of her own persecutors. (And sure, all poets are persecuted, or should be.)

She inaugurates at each moment these fine, hard little repeated processes and needs nothing else. There is an unnatural density to this equine mass. And a movement that shimmers from metamorphosis to fakery. Previous neat flowing lines now undulate. There is no sense of improvisation here because it seems everything was prepared long before. Reading is a sense of following the plan. There is gravity and grace as well as humour. For a short collection it lasts long. It has inexhaustible acts. It is like an underground chamber of bronze, rigid with a pile of cushions inside and an invisible thread. Every horse risks intoxication through Torset’s visits. The poems set their histories and abandom them to new paradox. The horses are the heroes who are chosen to become human and shake with hilarity from the inside at this. The birth of comedy is fixed in what bleeds out: Torset will tell anecdotes she’s only just finished telling, like a mad drunk. She is an adept of sophrosyne – the capacity to steer clear of extremes – not because extremes are alien to her inclinations but rather because to refresh the unfamiliarity of her chosen target – the horses and all that – she keeps them overwhelmingly familiar in their strangeness. It’s an exotic read and one which manages comedy with disaster, alternating and combining an exhausted realism with the infidelity of other impulses.

Torset bursts from time to time with stories, and often it can be frenzied, but mostly it’s not. There’s the restlessness of being clear-headed enough to know where the limits of an aside might best be. It isn’t an easy thing to keep the spell working and what is most decisively the case is her use of metaphor as memory. Every story, each fragment, comes from another. This is necessary. And what you sense is that Torset is confronting an immensity that is no doubt personal at some level but more importantly some naked vastness that requires poetry and its antiphrasis to accommodate. The bright world is continuous.

There is something spectral about this collection, as if what is being performed has been delayed but will happen eventually. I think this is what ‘Four Horses, No men’ means. Backwards.

About the Author

Vilde Bjerke Torset is a norwegian artist and poet based in LONDON. Her recent publications include the poetry books Apollinaire and Other Horses (If a Leaf Falls Press, 2022), WHAT IT MEANS WHEN YOU DREAMS : A to Z (AFV press, 2021), and the artist book PAREIDOLIA - Dotremont’s Daughter (Timglaset Ltd, 2020).

She has been commissioned by The British Museum, The Royal Norwegian Embassy, Kristiania University College, and The Poetry School, among others. Her performances, including both solo works and collaborations, have taken place at a range of national (UK) and international venues, including The British Museum, The National Centre for Writing, The Poetry Society, Jorvik Viking Centre, and London Rich Mix. She is a member of Norske Billedkunstnere and Norsk Tegnerforbund.

She is the founder and curator of SCRYPTH .