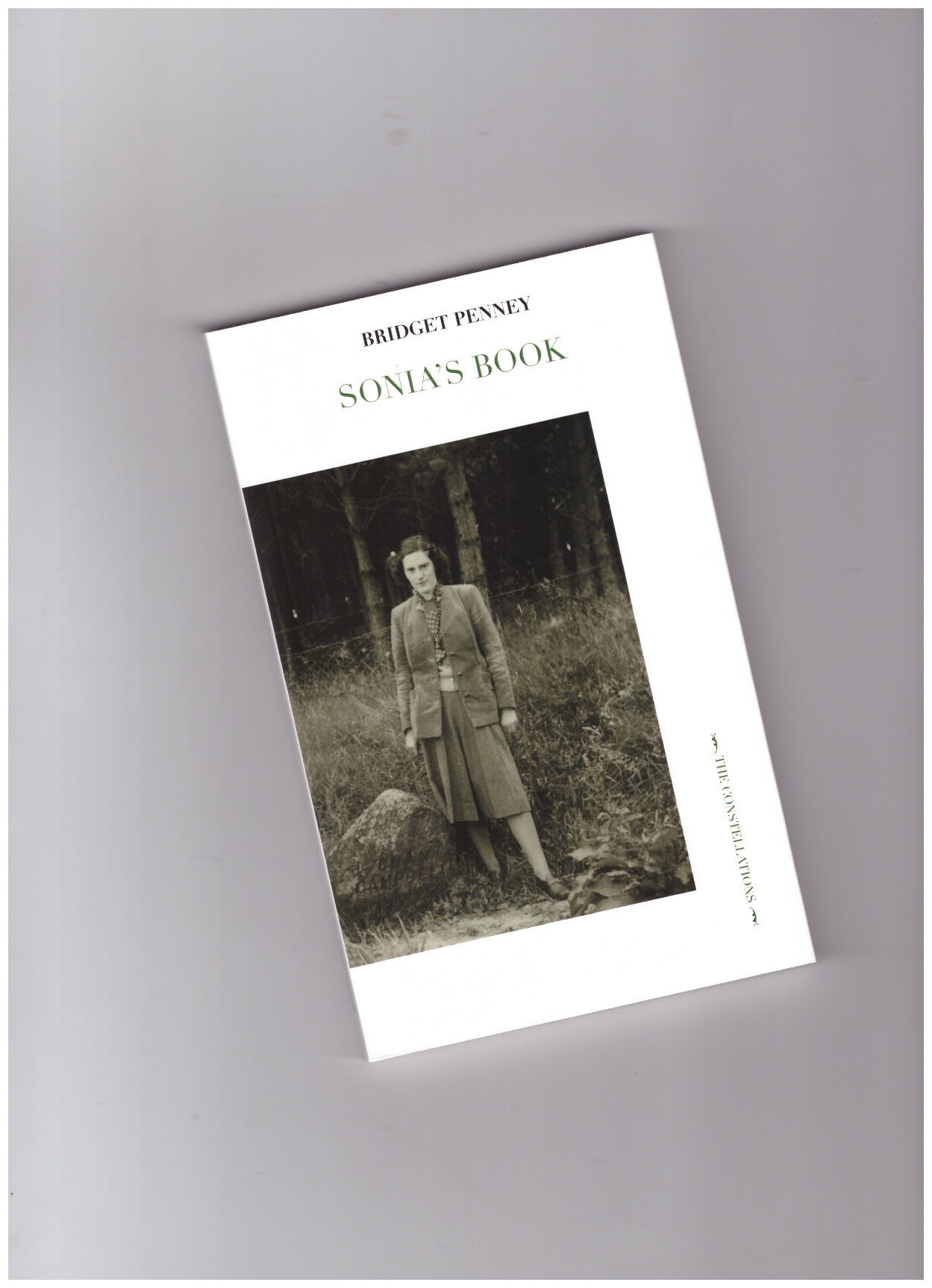

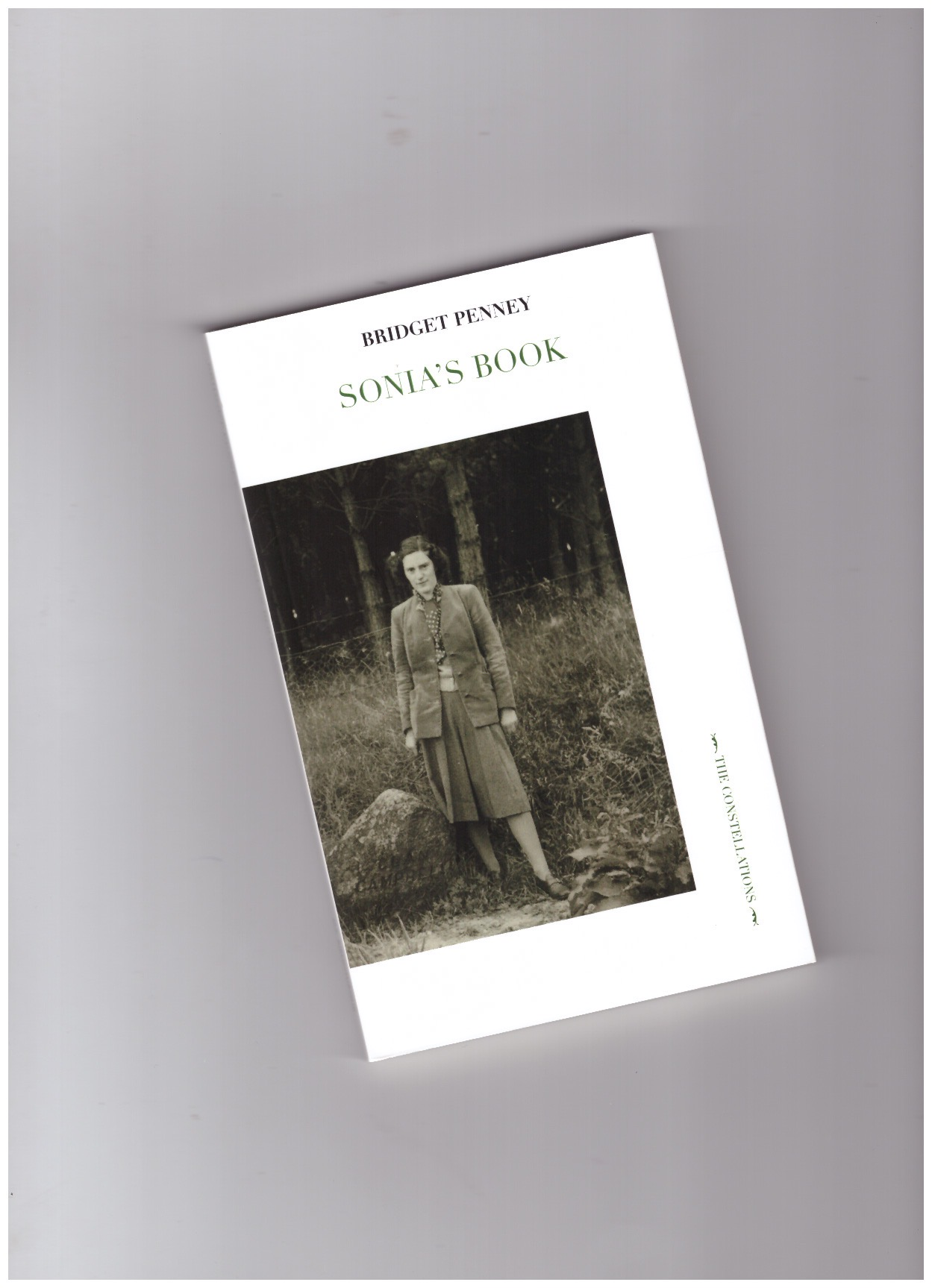

Bridget Penney's Sonia's Book

Bridget Penney: Sonia's Book

The object is simple. A small book, the record of another book, with plants pressed between pages and the signs of care noted one by one. The originating volume concerns natural history. The personal copy belonged to Sonia Campbell Penney. It held eleven sheets of pressed plants, blotting paper, pencil titles, a place name and date, Aviemore, May 1961. The new book takes those traces and looks at them. It looks again, and then again. It notes the tape, the alignments, the spelling, the thinness of paper, the way a petal tries to lift, the way a stalk lies flat because time and weight have trained it to lie flat. Nothing more is promised. The promise is kept.

What comes forward is a practice of attention that refuses to be narrative. Nothing begins. Nothing ends. What is offered is a sequence of close views that do not converge on a conclusion. The repeated form becomes the event. One pressed plant is described, then another pressed plant is described, with the same patience. The variation is small. The insistence is not small. The insistence becomes the shape of the book.In most forms of writing about books, description is a passage toward a claim. Here description is the claim. There is no colour introduced for mood. There is no climax. There is only accumulation. The accumulation is neither heap nor archive in the disciplinary sense. It is the pressure of repeated particulars that refuses any higher order than the order of attention. The writing accepts that order. It reproduces it. It trusts the small fact not as a symbol, only as itself, and the act of keeping that accompanies it.

The original object was itself an act of keeping. Someone took a guide, took plants, pressed them, interleaved blotting paper, wrote names, and held the pages together over time. This was not science, not in the formal sense, and not a diary with entries that lead up to a life story. It was a record of contact. The new book repeats that contact in another medium. It does not interpret. It sustains a contact with the contact. It is reading pushed past the point where reading produces meaning that can be paraphrased. The result is reading that is almost indistinguishable from handling. Each page reads the way a hand would handle. The page thinks with the fingertips, and it does so without metaphor, in a literal sequence.

The effect is marked by a particular kind of absence. When writing presumes to tell a story, the unit is the episode. When writing presumes to explain, the unit is the argument. Here neither unit applies. The unit is the faint shift of adhesive, the small gift of a pencil mark that is still legible after six decades, the slight difference between two guard sheets that look the same until the light changes. These units do not carry the text toward a goal. They exhaust themselves in being seen. The whole work proceeds without a project that could be completed. It is work that becomes unworked by its own rigour. The reader is not asked to arrive. The reader is asked to remain.

What then takes the place of arrival is a form of sharing without exchange. The reader and the author meet at the level of the detail and nowhere else. They do not share an opinion or a memory. They share an exposure to what will not generalise. This exposure has the shape of a community that exists only as long as nothing is forced to become common. The pressed plant will not give itself as an example of anything except being pressed. The book acknowledges that and holds the acknowledgement where a conclusion would usually be. The result is plain, and it is also exacting. The book refuses to produce more than what it has already produced, and the refusal is the coherence.

Because of the refusal, the prose is matter of fact. The tone is neutral, almost procedural. A specimen appears, its position is specified, its material support is named, the incidental marks are noted, and the sequence moves on. If a reader waits for a break in the procedure, there is no break. The sameness is the discipline. The repetition is a kind of honesty, a refusal to decorate the scene with colour or a dramatic swell. This is not because the subject is austere. It is because the book has chosen a fidelity to a practice. The practice is close attention to what has been kept, and the decision to remain at that level undoes the usual path from detail to meaning. Meaning, in the usual sense, is not missing. It is displaced. It sits in the quantity of the small, not in an extractable statement.

The quantity of the small creates a surplus. The surplus is neither data nor anecdote. It is the excess of presence that results when nothing is discarded to make a pattern. You can think of it as a kind of play, but the play is not a game with a set of winners and losers. It is the free movement that persists inside rules that have been chosen and do not change. The rule is that each pressed plant is given the same degree of regard. The free movement is the slight difference in how each page yields to that regard, the small surprises of texture, the mismatch between the name and the thing, the way the hand that wrote a word reveals a minor fatigue at the end of a long day. These forms of play are serious and light at once. They do not add up to a thesis. They add up to time spent.

There is also a form of contact that is intimate and without sentiment. A pressed flower in a family book is close to the language of affection, yet here the book does not turn the object into a token of affection. It keeps to the surface, and by doing so it stays with a different intimacy, the intimacy of pressure. Leaves and petals are held between papers. Tape is pressed and lifted and pressed again. Fingers leave a logic of spacing that another hand can later follow. The writing reproduces that logic. It does not draw conclusions about the life behind it. It recognises that the act of keeping is the life that matters for the purposes of the present book. If there is an eros here, it is the eros of touch that does not consume. It is the persistence of contact without possession, a sustained nearness that maintains distance as its condition.

In literature there are examples where repetition approaches a condition of bare life, where speech is the act of continuing rather than the act of saying something new. The comparison that suggests itself is technical, not thematic. There is the steady, almost mechanical return to the same operation, with differences that are not announced but must be registered. The new book uses that mode without the gloom often attached to it. It is practical. The subject is not the anguish of repetition. The subject is the simple fact that once you decide to look closely, you must continue to look closely, and this takes time and produces pages.This procedural quality might suggest a museum catalogue entry spread out into a long series. Yet a catalogue aims at completion and substitution. Once you have the catalogue entry you do not need the object. Here the writing does not substitute for the object. It does not capture. It stays with the knowledge that it cannot replace the feel of paper or the thin resist of old adhesive. The specificity of that knowledge gives the writing a modesty that is also a strength. It never claims to provide the thing. It provides the record of a looking that keeps the thing what it is.

What happens to the reader under these conditions is not boredom, or rather, if boredom arises, it is neither an error nor an obstacle. It can be treated as one more contact. Boredom in a situation of high attention is a measurement of how much the self demands change. The book does not satisfy that demand. It widens the situation in which the reader notices the self asking for climax or colour and then does not receive it. What remains is the residue of looking when entertainment is not the measure. That residue is oddly clarifying. It can be thought of as a trained patience that opens a small area in which recognition is delayed and perception can settle.

The figures that recur in such a field are mechanical and human at the same time. There is the rhythm of leaf, label, guard sheet, page edge, annotation. There is also the rhythm of the hand that finds a place to rest between one sentence and another. The book shows how both rhythms can coincide without fusing. It is a record of coordination. A body held a book and did small things to it. Another body, much later, held that same book and did small things in prose. The later body does not attempt to fix the earlier one in a story. It simply keeps the alignment. In doing so it produces a relation that is exact and slight. The two do not meet as characters. They meet as practitioners of a very small art.

Because the art is small, it has no drama of innovation. There is no turn where a new method appears. There is no test case. The whole has the plain profile of a routine where the routine is sufficient to sustain thought. When thought is separated from the need to present newness, it can become attentive in a different way. It is no longer the instrument of change. It is the scene of an ethical relation with what is given. The ethics here is uncomplicated. It is the refusal to force more out of a plant than the plant can sustain. It is the refusal to turn a handwriting into a confession. It is the refusal to transform a niece into a social historian or an aunt into an emblem of a period. These refusals produce the clearest sentences in the book.

The clarity is heightened by the format. The small scale denies the solemnity of large format art books. The narrowness of the page concentrates looking. Short lines accustom the eye to a pace that does not hurry. The page design supports the prose stance. The material facts of the edition are part of the argument that is not an argument. A book about keeping should keep itself within modest bounds. A book about attention should discourage the theatrical. In this way, even the dimensions and production choices rehearse the central practice. They are not clever. They are apt.

As the sequence continues, the reader becomes familiar with small terms that would be invisible in another context. A bit of tape that has yellowed will come to seem like a note in a piece of music. A line of pencil that thins before it ends will seem like a paused breath. These effects are not sentimental. They are the consequence of repetition. The mind, given a stable field, begins to register micro differences. It does not need to be prompted to discover a message. It needs only to be permitted to continue. When that permission is given, perception finds its own material. This is not mystical. It is the ordinary function of attention when it is not tasked with solving a problem.

In such a setting, memory behaves differently. Memory is not used to retrieve a life. It is deployed as a form of persistence. The reader remembers how a label looked three pages earlier to be able to notice how a later label sits differently on its paper. The memory is impersonal. It is a function of the sequence. In this way the book trains a practical kind of recollection, one that belongs to craft rather than to biography. The result is a gentle correction to familiar habits. We often think a family object asks to be folded into a family narrative. Here an object refuses that fold and remains stubbornly its own technical history.

The technical history is not narrow. It includes weather, time, and storage. A plant pressed in Scotland in May carries the season as a set of constraints and offerings. The blotting paper registers humidity. The old book records the intervals when it was moved or left alone. The new book reads those traces as part of the same practice of factual noticing. It does not need to say more than the facts in order to indicate that these factors are present. The presence is seen, not asserted. This is a quiet pedagogy. The text teaches the reader to see conditions without naming them as lessons.

A further feature of the work is the way it understands generosity. The author gives up privileges that would normally attend such an intimate object. She does not use the object as a springboard to memoir. She does not present it as a key to unlock a complicated family story. She gives the object back to itself. In literary terms this is a form of restraint. In ethical terms it is a form of care. Care here is the refusal to appropriate. It is the acceptance of limits. It is generous because it relinquishes the opportunity to be expressive. Instead, it allows the other thing, the pressed plant, the piece of paper, the minute technology of keeping, to occupy the space of the sentence.

What does a reader take from a work of this kind besides the experience of the pages themselves. One takes a method that is transferable in principle and resistant in practice. Transferable, because one can take the lesson that very small attentions can sustain a text. Resistant, because this lesson cannot be mass produced without the loss of its essential constraint. The method requires that the writer and the reader remain with the particular without turning it into a generality. That requirement is hard to expand into a system. It requires the opposite, an unworking of system, an ongoing deferral of the move by which a set of details becomes a thesis. The book insists on that deferral all the way through.

Because of this, the prose produces a space that feels both public and private. Public, because it maintains distance and refrains from confession. Private, because it honours a singular relation that does not need to be explained. The feel is unusual. It unsettles one conventional measure of literary success, the measure by which a work is judged to have brought its materials to a decisive point. This work is decisive in another way. It decides to let the materials remain undecided, and in that decision it finds its balance. For a reader accustomed to narrative, this can seem like the absence of movement. In fact, the movement is continuous but faint. It is the slow change of a surface under prolonged attention.

This faintness of change has a large consequence. It redistributes value. A plant scrap that would be worthless in any market becomes the centre of a page. A smudge is not noise. It is an element with a position and a weight. The hierarchy between subject and background is levelled. The page becomes a field rather than a figure. The writing becomes a field of evenly weighted observations, so the reader can move through it without being directed to a summit. This is not indifference. It is a different economy. It is an economy in which excess is not burned off to reach clarity. Excess is kept, and clarity is built inside it by the patience of the sentences.

Such an economy is playful in a restrained sense. To play, in this mode, is to persist in an activity that has no external goal beyond its own continuation. The making of pages that repeat a form is play. The reading of them is also play. Not frivolous, not solemn, simply sustained. Within that play, small liberties can be taken. A label can be left slightly askew. A description can allow itself a mild aside about the way light touches a cellulose fibre. These liberties are not commentary. They are micro adjustments in the ongoing game by which attention keeps itself from hardening into law. The book permits these adjustments rarely, and when it does, they function as proof of life rather than personality.

It is useful to say that this work treats evidence without constructing a case. The plant fragments, the blotters, the tape, and the notes would normally be marshalled to support claims, scientific or historical or sentimental. Here the evidence is relieved of that pressure. It is allowed to remain evidence without a court. The relief is palpable. The reader can breathe inside it. Freed from the need to convict a thesis, the details can be themselves. This does not reduce their significance. To the contrary, it grants them a kind of quiet authority, the authority of the small that persists without insisting.

The attention to small things allows for a precise sense of time. Not time as a narrative arc, but time as duration with measure. You can measure how the adhesive ages. You can measure how pencil remains steady compared to inks that might have faded. You can measure the time of the original pressing and the long time of storage, and the present time of looking. The book does not pronounce on these measures. It enacts them. Each sentence that records a minute fact is one more second in a sustained duration. The duration is not an allegory. It is the texture of the work. There is a discipline in keeping the duration going that is akin to the discipline of a laboratory method or a craft routine. The difference is that this discipline offers no result beyond its own maintenance. That is a hard lesson for readers who expect payoff. It rewards readers who accept staying as a mode of thought.

A question arises about whether such staying is a kind of refusal of the world. The answer is practical rather than theoretical. The book does not retreat. It faces a small corner of the world and gives it its due without claiming that the corner is the world. That is neither withdrawal nor grandiosity. It is proportion. Proportion has become rare in a field where claims grow large to attract attention. This work is not indifferent to attention. It simply will not purchase attention with inflation. It holds to scale. That holding is, in its plain way, exemplary.

The object under view is a book that kept plants. The viewer is a writer who kept viewing. The relation between the two is the subject. Between them stands a third term, the reader, who must decide whether to accept the terms of the relation. If one accepts, the experience is unhurried and exact. If one does not, the experience may seem flat. There is no way to correct this from outside. The book is honest about that. It does not lure or instruct. It does not flatter by offering hidden meanings. It lays out the sheets. It lets the reader lay out their attention beside them. In that adjacency, a small community forms, a community of persons and pages who agree not to demand more than what is given.

It is reasonable to ask whether the work is a model. It is a model only in the sense that it shows how a disciplined refusal can produce a workable form. It is not a template for other books, unless those other books begin with other small worlds and grant them the same rigour. The particularity is not accidental. The peculiar scale of the original object, the family linkage that both invites and forbids narrative expansion, the endearing and resistant quality of plants that are no longer living yet have not vanished, these elements make this book possible and not another. The method is general. The material is not. This balance between general method and singular matter is a source of calm in the work. It allows the book to be confident without being loud.

The confidence expresses itself as exact naming. Names are not exploited for metaphor. They are held at the literal level, both when the subject is a plant specimen and when the subject is a piece of paper. The writing refuses to use things up. To refuse to use things up is a kind of love that does not make claims. It is patient. It does not ask to be repaid. It is not needy. In a small way that matters, the book teaches this kind of relation. It teaches it by example. It does not propound a doctrine of it. It practises it until the reader feels what it is like to be in such a relation for an hour or two.

All of this might sound doctrinal when said at length. The book itself is not doctrinal. It is brief in its movements, and the movements repeat, which is a form of modesty. It does not claim to break ground. It does not claim to heal. It does not assign the original keeper a role beyond the one she actually played, which is the role of a person who kept plants between pages in the spring of 1961. This unadorned stance is rare in a literary culture that finds it difficult to leave anything unclaimed. The refusal to claim becomes the mark of the work.

The mark is also a kindness. A reader is asked to look. To look in this way requires nothing that an ordinary person cannot give. It does not require expertise beyond the willingness to follow a sequence. If high theory sometimes assures us that only the initiated can see the structure of things, this work counters that assurance with the proposition that anyone can see a torn edge and understand that the torn edge is not an invitation to a grand interpretation, but is only the given fact needing attention. This modesty is not a lowering of aim. It is an exact match between aim and material.

There is, at a quiet level, a sense of play that runs through the pages. Not the play of jokes, though a light humour appears when a caption winks at a minor misalignment. The play is the freedom that comes when one stays within rules and finds room to breathe. The rule is simple. Attend to what is there and do not add. Within that rule, the sentences shift a little, the eye revisits an earlier page to confirm a hunch, the hand pauses. The repetition of the rule is not mechanical in the dead sense. It is like a musician returning to scales that are never exactly the same twice, because the day is different and the body is different and the ear is sharpening. That is the air of the book. It is most present when nothing appears to happen.

Because the book stays with the unexciting, it produces a particular aftereffect. When you close it, the rooms around you look more detailed. You see small seams. You notice tape on the edge of a shelf more than you did before. You become aware of how objects in your possession carry minute marks of keeping. This is not an enlargement of taste. It is a reweighting of attention. The book works on the reader by this reweighting rather than by the delivery of lessons or stories. The change is local and portable. It is not a transformation. It is not advertised. It is useful.

The usefulness extends to how one thinks about reading. A close reading that does not become commentary teaches a limit. The limit is the point at which words would begin to replace the thing they are seeing. Stop before that point. Remain on the edge where words still serve the thing. This is not a ban on thought. It is an orientation. It corrects a common temptation, the temptation to proceed from a detail to a position and then to use the detail only as a step toward the position. Here the detail does not become a step. It remains a place where one can stand. The book invites the reader to accept that as sufficient.

Because of this orientation, the work may seem severe. In truth it is gentle. Severity would be the enforcement of a rule for its own sake. Gentleness keeps the rule in order to keep faith with the object. The distinction is exact. It is the difference between rigidity and steadiness. The prose is steady. It does not scold. It does not boast. It keeps time. In keeping time, it approaches a form of community that does not rely on agreement. The reader, the writer, and the keeper of the plants are together without needing to share anything that could be voted on. They are together by proximity to a page. This is a slight togetherness. It is also a true one. It cannot be enlarged. It can only be sustained.

At the edge of such sustaining, one might ask about loss. Are we losing narrative, colour, climax. Yes, those things are set aside. But what is gained is not a theory of loss. What is gained is an alteration of scale. At this scale, a climax would be an intrusion. Colour, in the sense of flourish, would be a violation. Narrative would distort the proportion between the plant and the page. The gains are fit to the losses. The balance is exact. That exactness is the reason the book feels complete even though it avoids the usual markers of completion. Completion is not what happens at the end of a story. It is what happens when a chosen form is sustained without betrayal.

If one were to evaluate the work by comparison, a certain lineage appears. There are other writers who have pursued minimal procedures to their ends. In those works, repetition is often associated with an existential condition. Here repetition is simply the condition of looking long at something small. One can say that the book belongs to that lineage in method, not in mood. The mood is daylight. The feeling is not despair. It is economy. It is the correct proportion between a simple task and the time it takes to do it well.

There are writers who have taken this procedure of patient, almost mechanical regard and pushed it until it becomes its own content. Samuel Beckett’s late prose, especially the small blocks that proceed by attrition rather than plot, is one locus. Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons names without exhausting, keeping language close to things in a way that refuses summary. Francis Ponge’s brief pieces on ordinary objects sustain a factual poise that resists allegory. Georges Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris turns looking into a day’s work, a method of listing that never demands climax. Joe Brainard’s I Remember accumulates units that do not argue, they simply hold. Lydia Davis’s The Cows shows how steadfast attention can become a form without ornament. R. F. Langley’s diaries practise a craft of seeing that trusts the smallest sign. Bernadette Mayer’s Memory extends the routine of noting until it becomes duration itself. John Cage’s “Lecture on Nothing” models a rule-bound play that proceeds by repetition without crescendo. Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit proposes instructions that make perception a task. Sophie Calle’s procedural works, such as Suite Vénitienne, keep to method so strictly that method becomes the scene. None of these offer a template here, but they confirm that a text can be built from steady noticing and an even distribution of attention.

This makes the book succeed by virtue of persistence, clarity, and the balance of attention. It will not be admired by everyone. It does not seek to be. Such seeking would contradict the refusal that gives it integrity. For readers willing to enter its scale, the reward is calm. For readers unwilling, the book passes by them without conflict. This too is a kind of success. To exist without clamour in a clamorous world is an accomplishment.

In the end, the appropriate response is not explanation. It is acknowledgment. Here is a book that takes close reading beyond close, keeps it so close that it excludes the forms we expect from reading, the arc, the rush, the highlighted passage that seems to solve a problem. It offers, instead, repeated details page after page, a strange accumulation, like a table slowly filling with small stones that no one counts and no one discards. The stones are not symbols. They are what they are, and the act of setting them down is the content of the work. To describe this as slight would be to mistake the nature of scale. To describe it as heavy would be to miss the lightness of its play. It is neither. It is exact.

Exactness is rare because it is not easily traded. It cannot be summarised without loss. It cannot be displayed at a distance. It must be entered. Once entered it sustains itself with no help from outside. That self sustaining quality is the final mark of the work. It leaves the reader without a conclusion because none is needed. The reader has been kept in company with pages that keep, and in that company the usual instruments of reading fall silent, not because they are wrong, but because they are not required. What remains is a minor masterpiece, durable accord between the eye, the page, and the small thing kept. That is the whole matter, and it is enough.