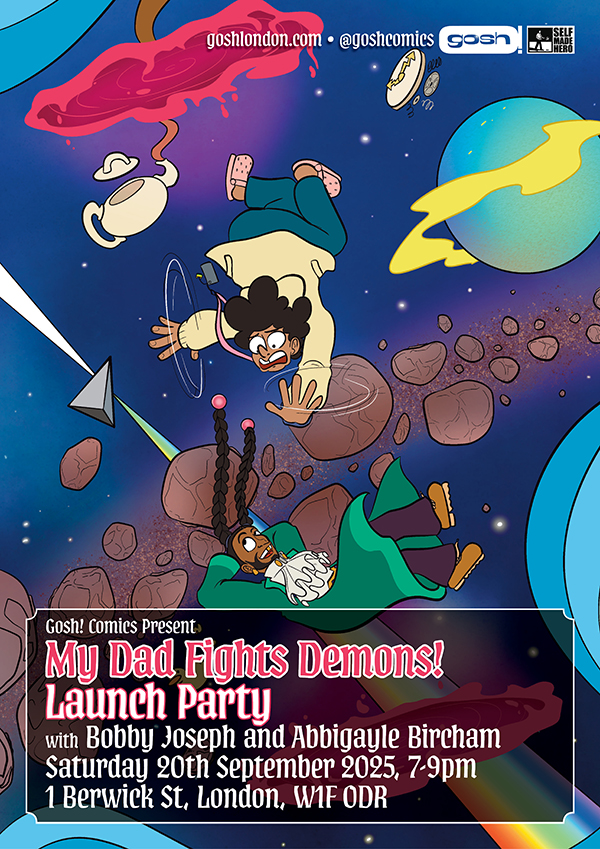

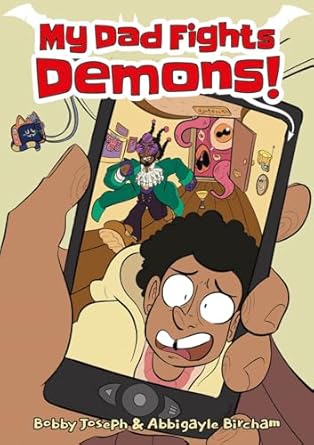

Bobby Joseph's My Dad Fights Demons

This week past ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel after on-air remarks ridiculing MAGA while discussing reactions to the killing of activist Charlie Kirk, a move that drew public pressure from FCC chair Brendan Carr and prompted a wave of on-air solidarity from Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Fallon and Seth Meyers, who all framed the suspension as censorship. Colbert then devoted an episode to Kimmel’s case, even as his own programme had already been cancelled by CBS, with The Late Show slated to end in May 2026. Humour is a serious business now that the fascists are back in town. I live near where Charlie Chaplin went to school in Hanwell, West London, the Chaplin who mocked Hitler in Modern Times, a film whose title was used knowingly by Bob Dylan who looked like Chaplin at the start of his career and looks like him again. Both knew a thing or two about laughing at power. Bobby Joseph’s My Dad Fights Demons! joins them and does so in a way that links to an enduring tradition of English humour.

Joseph is a South London writer and editor who built platforms when none were offered. He created Skank in the nineties and gave Black and Asian voices a place to swagger and a place to joke and a place to refuse tidy frames. He carried the energy into Scotland Yardie. He wrote columns for broadsheets and the style press. He taught in classrooms where comics became engines for literacy and confidence. He now serves as UK Comics Laureate for 2023 to 2025 and is the first person of colour to hold that role. A national brief to support libraries and young readers flows into the book’s shape and into its tone. If the new novel feels like a culture wide invitation that is because Joseph has been building a guest list since the days of photocopied zines and small press stalls.

So what's the tradition I'm saying Joseph's great new book fits right in with. Well, England’s funniest work has always doubled as a civic practice. It entertains, and at the same time it trains the eye to look straight at power, snobbery and cruelty without blinking. You hear it on the radio, you see it on television and in films, and you meet it early in children’s books and comics. Jokes become a public language for saying what is wrong, for keeping people together when life is tight, and for insisting that common sense belongs to everyone.

Radio made this habit national. Programmes such as The Goon Show, Hancock’s Half Hour and Round the Horne taught listeners that authority can be made ridiculous simply by taking its voice literally and following it to the end of a sentence. Satire became a weekly check on the news with That Was The Week That Was and later The News Quiz and The Now Show. Dead Ringers gave the country a way to hold the powerful in the mind by pinning a sound and a line to them. On the Hour worked out how to parody the rhythms of news itself and let audiences hear how a bulletin can be shaped to flatter or to frighten. These shows were funny first, yet they also taught technique. They showed how to puncture puffed up claims, how to separate tone from substance, and how to use a punchline to expose the trick in a piece of rhetoric.

Television broadened the field and deepened the reach. The moment that often gets replayed is the class sketch from The Frost Report with John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett. Three men stand in a row and tell you where they fit in the class system by looking up or down and speaking in turns. It lasts only a few minutes and it has never stopped working. It does not scold. It shows how language and posture do the job of hierarchy. Dad’s Army, often remembered as a gentle wartime sitcom, turned pomposity into a running joke and quietly insisted that dignity is not the same as rank. Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister explained Whitehall without a diagram. They put ambition, caution and office politics into scenes that play like farce and end as lessons in how institutions defend themselves. Blackadder used history to look at the twentieth century’s most painful subject. The final scene of Blackadder Goes Forth is remembered because it refuses the easy laugh and makes the audience sit with the cost of blunder and vanity. There's a victim of the Somme in a nearby graveyard and that Blackadder episode is as powerful a way to understand its tragic universal and personal meaning as anything.

The satirical current stayed strong. Spitting Image gave an entire generation a puppet vocabulary for public life and showed that caricature can be a form of evidence. The Day Today and Brass Eye made the machinery of television visible. They revealed that authority often lives in graphics, music and voice-over more than in facts. The Office and Peep Show turned their gaze on work and friendship and found the quiet tyranny of small rooms and small humiliations, which is where class and gender rules often do their daily harm. The Thick of It taught viewers how spin is made and why it breaks. It did this through scenes that are as precisely staged as they are profane. People Just Do Nothing and This Country returned to working and rural lives and restored affection and detail without losing the bite.

Stand up threaded through these decades and kept the pressure direct. From Alexei Sayle and Ben Elton in the eighties to Stewart Lee, Josie Long, Nish Kumar, Lenny Henry, Gina Yashere and many others, rooms full of strangers were asked to test their own assumptions and to laugh at the solemnity of the day’s headlines. The best sets took apart the clichés used about race and gender and class and left an audience with a cleaner set of words for the week. The point was not to shame people. The point was to show how a lazy story empties out your head and how a better story handed to you with a laugh stays in place long enough to resist the next round of nonsense.

Cinema added reach and variety. The Ealing comedies set an early template. Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Ladykillers use crime as a formal frame and class as the true topic. You laugh because the plot is neat and the performances are exact, and you leave with a clearer sense of how status turns people into characters. The Python films brought absurdism to questions that make officials nervous. Life of Brian treats groupthink and religious spectacle with jokes that make the idea, rather than the believer, the object of attention. Mike Leigh’s films sit closer to the ground. They find comedy in awkward conversations and in rooms where class and gender rules press hard. Ken Loach carried humour inside serious stories of work and welfare. In the Loop pushed the political farce of The Thick of It onto the world stage and made real policy stakes collide with the need to look good on television. Four Lions took the riskiest subject of its time and refused both panic and smugness. It reminded audiences that foolishness and grievance, rather than grand theory, drive many bad ends.

Children’s literature carried the same spirit to younger readers. Lewis Carroll trained generations to question authority through logic games. E. Nesbit treated politics as something that happens in a family and on a platform while you wait for a train. Richmal Crompton’s Just William took a boy’s eye view of adult pretension. Roald Dahl set bullies and snobs against children who read and think and refuse to be frightened. Philip Pullman gave young readers a moral education in how to treat dogma and the state. Malorie Blackman asked her audience to test what they think they know about race by flipping the script and staying with the discomfort long enough to learn. Michael Rosen showed how language can carry grief and solidarity at the same time. Judith Kerr and Raymond Briggs proved that pictures can carry dangers and comforts that prose alone cannot hold. When the Wind Blows makes policy shockingly intimate. Ethel and Ernest records working class life with line and colour and holds it steady so the viewer can pay proper attention.

Comics have always been a democratic classroom. The Beano and The Dandy taught generations to distrust the bossy and to forgive the unruly child who trespasses against tidiness. Leo Baxendale designed pages that run on speed and surprise yet always leave space for the feeling that the kid has a point. 2000 AD taught readers how to look at the police and the law with a colder eye by making Judge Dredd both hero and warning. Charley’s War pulled the glamour out of the First World War and gave the reader a long apprenticeship in sympathy and suspicion. Posy Simmonds created adult graphic novels that satirise media and class without losing sight of the person inside the types. Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta turned a mask into a question about the relationship between fear, spectacle and consent. Bryan Talbot used the form to speak clearly about harm, recovery and the shape of a town. Private Eye kept cartooning lively and helped people connect politics to a face and a posture.Humour has also been a tool against racism and sexism. The Real McCoy and Goodness Gracious Me put Black and South Asian life into millions of living rooms and let audiences see how stereotype collapses when it has to survive a joke told from the other side. Sketches that reverse the direction of a cliché or play it to the point of absurdity do more than entertain. They change what can be said in a home or a school the next day. Sitcoms like Chewing Gum and dramas with strong comic spines like Fleabag and I May Destroy You brought sexual politics into view without treating women as symbols. They insist on detail and the right to be awkward, funny and wrong in public, which is the opposite of being reduced to a lesson.

English humour also keeps a place for the jester and the fool. Shakespeare understood that the person officially licensed to joke can say the hardest thing. The lineage runs through music hall, through the wireless and into television studios and clubs. The aim is not to humiliate. The aim is to tell the truth without the consolation of solemnity. Absurdism protects freedom by refusing the tidy grid. The Goon Show, Monty Python, The Young Ones, Vic and Bob, The Day Today and Brass Eye made a practice of side steps and sudden turns. They remind audiences that real life does not fit in a neat box and that any voice claiming total control over feelings and conscience should be laughed at until it loosens its grip. The late great Steven Wells wrote some of the sketches for The Day Today and his Attack! Books were of the same tradition of irreverent and surreal humour with a satirical bite.

Class snobbery remains an evergreen subject. Keeping Up Appearances, Steptoe and Son, Porridge, Only Fools and Horses, Blackadder, Yes Minister, The Royle Family, The Office and Peep Show strip titles, accents and job descriptions of their glamour. They reveal a simple truth. Worth has very little to do with rank. Wisdom and grace appear where people look after one another and endure. The laughter comes from recognition rather than cruelty. We have met these people and we know the difference between swagger and competence.The same pattern holds in satire that faces government more directly. A weekly panel show like Have I Got News For You accustoms viewers to the idea that public claims are raw material for jokes and questions. Charlie Brooker’s Wipe series trained people to treat the week’s media as an object of study rather than as a stream to be swallowed. Stewart Lee’s long form sets used silence and repetition to show how crowd pressure works and how it can be resisted. Each of these shows encourages a habit of attention. They ask the public to listen for the extra word in a sentence that reveals a motive and to notice when a graphic or a soundtrack is doing work that a fact will not.If you ask how all of this binds rather than divides, the answer is in the subjects that recur. A place to live. A school that cares. A surgery that answers the phone. A wage that leaves room for rest. Peace on the street and parks where you can sit in the shade. Neighbours who look out for one another. English humour puts these simple things on stage and refuses to let them be dismissed as small. The joke protects them. It shames the voice that treats them as unworthy of attention. It invites a wide audience to take pride in ordinary decency and to laugh at the swagger that tries to hide unfairness behind a title or a slogan.

This habit reaches back further than broadcast and print. Hogarth’s engravings turned London into a school of looking and showed how drink, greed and pride distort a face. Contemporary artist Grayson Perry recently showed his own updated version of Hogarth in the same spirit. Gillray and Cruikshank gave politics a theatre of expressions and taught viewers to read a nose or a chin as the trace of a policy. Their pictures were public conversations in an age before rolling news. They did not wait for permission to name a vice. They made the vice obvious and invited the street to judge. Modern cartoonists continue the line in newspapers and on screens. A single drawing can sometimes break through where a thousand words blur.

There is a generosity at the centre of this tradition. The work mocks the powerful and the puffed up, but it protects the ordinary person. Giles cartoons used to do this. It prefers the quick eye to the heavy hand. It thinks children are clever and gives them puzzles rather than lectures. It thinks adults can learn without being scolded. It believes that communities stay together when they can laugh at shared targets and share a store of lines and scenes that define what is decent. A country that has that store is harder to fool and harder to bully.

The result is a long record of stories and sketches and songs that help people see the times they live in. They are not simply distractions. They are forms that let a city or a village or a family recognise itself and speak back. When war, racism, sexism and poverty make life small, humour returns scale to the person on the receiving end. When official voices become pompous or vague, humour cuts them to size. When a new idea challenges a settled comfort, humour can lower the guard just enough for the idea to be heard. This is why the tradition has lasted. It proves itself useful in quiet weeks and in difficult seasons.

England’s television, film, radio, children’s literature and comics have made this practice a habit rather than a special event. The best shows and books are funny and they also teach the public how to keep its balance. They laugh at class snobbery and at racists and sexists and at every little cruelty that hides in a rule or a glance. They celebrate free thinking. They bind people who do not know each other by giving them a shared scene to remember and a shared line to say.

So Bobby Joseph’s My Dad Fights Demons sits right inside the English tradition of speaking plainly to power with a grin, and it refreshes that habit for the readers who will carry it next. The book uses the same public language that radio, television, films, children’s literature and comics have refined for a century. It treats comedy as a civic tool. It names what hurts without preaching. It prizes quick eyes over heavy hands. It makes the small things that keep families and neighbours going feel central rather than marginal. It does all of this in a form that travels easily from a school library to a bus ride home.

Start with the setting and the way the jokes arrive. Joseph places Rye in recognisable rooms and on ordinary streets. The first beats are domestic and slightly embarrassing. A conversation in the loo becomes a life reveal. The scene shifts to a portal fight that feels like a Saturday morning cartoon made by people who have stood in long queues and missed the bus. The reunion on the pavement gathers goblins, a cloud chauffeur called Gobby ( of course a sly dig at Harry Potter), and a father who carries chaos into any postcode he enters. This is classic English staging. The extraordinary walks into an ordinary room and everyone keeps talking. Dad’s Army did it in a church hall. The Ealing films did it in boarding houses and bank offices. The Beano has done it for generations with teachers and prefects who never quite manage to be in charge. Joseph follows the same rule. The comedy starts from the ground. It is not a break from real life. It is how real life is lived when money is tight and time is short.

Fantasy sits inside this tradition as a way to tell the truth in disguise, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where logic is pushed until power looks silly, to Doctor Who, which takes police boxes, school corridors and bus stops and lets time travel expose character, courage and bluff, and to Harry Potter, where school routines, prefects and the Ministry’s paperwork turn magic into a study of class, prejudice and resistance while jokes and pranks become a practical form of dissent. Joseph’s book belongs to the same current. Joseph’s fantasy also sits comfortably beside children’s television that brings magic through the front door and keeps the room recognisable. Think of The Box of Delights, The Demon Headmaster, Moondial, Children of the Stones, The Owl Service, The Borrowers, The Snow Spider, Knightmare, The Worst Witch and Wizards vs Aliens. Each of these shows builds clear rules for the extraordinary, anchors them in ordinary places and uses the adventure to test character and community. My Dad Fights Demons works the same way. Portals open off kitchen tiles and pavements. A fight scene follows rules you can grasp in a breath. Jokes lighten the mood exactly when a young reader needs air, then the story returns to what counts, who shows up, who listens, who learns. The structure will be familiar to anyone who grew up with BBC fantasy serials where the supernatural does not erase school runs, chores or bus timetables. It is the same rhythm, only drawn with elastic faces and quick panels.

Set Joseph’s world beside classic fantasy novels and the lineage is just as clear. There is Alice finding the limits of authority by pushing logic until it falls apart. There is E. Nesbit blending everyday London with sand-fairies and carpet rides so that kindness and nerve, rather than bloodlines, settle the question of worth. There is Alan Garner bringing old stones and fields into the present tense and asking children to carry more than they thought they could. There is Susan Cooper’s winter light and the idea that watchfulness is a skill. There is Diana Wynne Jones’s taste for capricious magic and chaotic mentors, where power is secondary to responsibility. There is C. S. Lewis showing how a wardrobe opens onto a moral map and how small choices scale up. There is Philip Pullman’s demand that young readers trust their own conscience. There is Rowling’s school story where authority is often its own problem and jokes and pranks double as dissent. Joseph’s book shares their plainest strengths. It makes the rules of wonder legible, it keeps faith with the ordinary texture of life, and it uses the impossible to test attention, loyalty and care.

The point of contact with children’s television is practical craft. A serial like The Demon Headmaster or The Worst Witch gives the viewer a clean line through each episode so the comedy and the set piece land without confusion. Joseph and Abbigayle Bircham apply the same discipline to the page. Panels that handle home life are steady and roomy. Panels that handle magic tilt, tighten and release in short bursts so eyes never get lost. Captions sit where they anchor the beat. Sound effects draw attention to the exact moment you should feel impact or movement. A child can follow the plot on first pass. A second pass reveals how the page manages time, emphasis and payoff. It is the comics version of television blocking and cutting.

There is also the figure of the mentor, and here Joseph belongs with Diana Wynne Jones and with CBBC’s own gallery of good-hearted chaos merchants. Mr Mantrikz has power and charm and blind spots. He can win a duel on a rooftop and still fail to hear what Rye just said in the kitchen. That mix of competence and foolishness is a staple of English children’s fantasy because it allows the young lead to grow without having to submit to perfect authority. Howl misplaces priorities until someone calls him to order. The Doctor saves a planet and then needs a friend to say stop. In Joseph’s hands the mentor is also a father, so the genre device carries an everyday question that the book keeps returning to. Who is reliable? What does presence look like? Who apologises and changes?

This tradition trained viewers to read space and rules quickly and because of it you can see why Joseph’s fights and puzzles are so satisfying. The comic spells out just enough logic for a scene. A boundary is drawn, a rule is set, then the page lets you watch the characters play inside those limits. That trust in fair play is part of why the humour lands. A silly image or a fast quip does not arrive from nowhere. It arrives on the beat the story has taught you to expect. The result feels like a game you have learned to play while you read.

The book also lines up with novels that bring magic into homes and schools without losing sight of class, friendship and small economics. Think of Skellig, Coraline, The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, The Ghost of Thomas Kempe, The Snow Spider and the Tiffany Aching books. Each treats wonder as a way to look more closely at a kitchen table and a street. Joseph does the same. Money, time and space are real limits. The fantasy does not erase them. It shows who navigates them with care and who hides behind noise. That is where the comedy does its quiet work. It invites the reader to laugh and then notice who did what and why it mattered.

Children’s television often earns its strongest moments when it places the uncanny against the most English of backdrops. A village green with something wrong under it. A school corridor that bends into another century. A bus stop where a friend returns with different eyes. Joseph’s pages work with that same contrast. A portal glows in a hallway that needs a coat of paint. A demon is banished next to a shop window that reflects everyone in the scene. A joke about snacks lands just before a serious line about promises. The familiar holds the fantastic steady so the reader can weigh what is happening without getting lost in spectacle.

All of this makes My Dad Fights Demons feel like a natural continuation of the stories that taught so many readers how to read pictures and how to measure courage. It speaks fluent children’s television and fluent classic fantasy while being itself. You can feel the shared grammar in the way an episode starts and ends, in the clarity of the rules, in the balance of threat and reassurance. You can also feel Joseph and Bircham adding their own emphasis. The art gives the faces a comic elasticity that suits embarrassment and bravado and the soft look that follows a loud scene. The script trusts a young reader with wit, with silence and with subtext. The world on the page feels like a place a camera could visit tomorrow. That blend is the English method at its best, ordinary rooms with extraordinary visitors, jokes that serve seeing, and a story that brings everyone in.

That same exchange between children’s literature and English film helps explain why Joseph’s book feels so immediately comprehensible. The directors Powell and Pressburger, for example, are not writing for children, yet their use of plainly drawn otherworlds, guides who speak like ushers, and fair-play rules that govern impossible spaces comes straight out of the story grammar that Carroll and Nesbit made familiar. My Dad Fights Demons works with the same grammar at street level. Portals open off a pavement or a landing; a demon encounter follows rules you can grasp in a panel or two; a joke doubles as a test of character; a reunion scene plays like a moral hearing that happens to involve magic. The clarity is the point. As in A Matter of Life and Death, the supernatural frame does not distance the feeling, it sharpens it. Joseph borrows the clean shapes of children’s fantasy so big themes can play out in images anyone can follow, then anchors them in kitchens, bus stops and school corridors that could be filmed tomorrow.You can see the film influence in the staging. Scenes set up like shots, page turns timed like cuts, captions that behave like voice-over and so on. The book adopts the English habit of letting the extraordinary walk into the ordinary without breaking the room, a habit that runs from Nesbit and Garner to Powell and Pressburger and on to Doctor Who and Harry Potter. The rules of the other place are simple enough to keep the spotlight on care, duty and bluff, which is why the fantasy never floats away from real life. Joseph’s portals do what Powell and Pressburger’s staircase and courtroom do for adults. They create a clear frame where attention, love, loyalty and responsibility can be weighed in public, and they let humour carry the weight without blunting it.

The figure of Mr Mantrikz fits another long thread. English humour keeps a place for the fool who is licensed to say hard things and to expose the limits of status. Shakespeare gave that licence to Feste and to Lear’s Fool. Music hall kept it alive. Television gave it to Basil Fawlty without giving him wisdom. Joseph gives it to the absent then returning father whose magic is real but whose sense of care needs work. Mr Mantrikz boasts and blunders and still forces the truth into the open. His bravado and his improvisation show what a child already knows. Authority is often a costume. Real responsibility looks quieter and takes longer. The book uses his foolishness to strip away puffed up performances of masculinity and to turn a question into a scene. Who is looking after whom? Who sets the tone in a family? What does being present actually mean?

Rye’s point of view keeps the book honest. Here the tradition of children’s literature meets the tradition of adult satire. Alice learned to puncture official voices by following their logic until it failed. Pullman taught readers to test dogma by asking who gets hurt and who gets helped. Dahl made bullies ridiculous and gave courage a plain face. Joseph takes that same trust in a young reader’s judgement and builds the pages around it. Rye is never a symbol and never a device. Rye is a person. Rye asks the questions that clear the room of grown up excuses. The result is anti racism and anti sexism as practice rather than posture. The world around Rye is mixed and specific. Stereotypes do not survive because detail displaces them. Blustering men look silly. Care is counted as action rather than as tone. Respectability cannot find a podium because the story keeps returning to who is doing the work.

The comic mechanics serve that politics. Panels are arranged so that domestic scenes sit in squares that keep the eye steady. When magic erupts the grid tilts, borders break, and the reader feels the shake in the page without losing the line of action. This is the craft that English comics have taught for decades. Leo Baxendale’s anarchy in Bash Street is built on clean geography. 2000 AD’s action reads at speed because the staging is precise. Posy Simmonds can load a page with social detail because the composition always gives you a safe path through it. Abbigayle Bircham works with the same discipline. Faces act. Bodies telegraph motion before the words arrive. You can follow a brawl at a glance and then see the smaller joke inside the swing. Colour keeps emphasis clear. Lettering is placed where the eye naturally looks. Sound effects land where the beat falls, so the punchline feels timed rather than pasted on. Captions are used as signposts. They label place and mark jumps in time. They lighten or darken the mood by a few degrees so scene changes are smooth. Younger readers can read the book by riding the balloons and pictures. Older readers can slow down and notice how caption placement, inset frames and gutter widths control pace and emphasis. None of this announces itself. It simply works.

The gags themselves travel in several registers at once. A child can laugh at a goblin being turned into a chicken and at a cloud that takes orders like a taxi. An adult can hear a familiar sentence about boundaries and see how the joke turns it inside out. The book uses register clashes, running bits and neatly placed asides that draw attention to how adults talk when they are hiding something. This is part of the English habit of two level comedy. The Goon Show trained listeners to enjoy the silly sound while catching the sly policy line underneath. Python put learned references next to dead parrots and surrealist nonsense and left the audience to sort the connection. I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue continues to show how surrealism and absurdism are very much part of English humour. The best family films tell two stories at once and trust everyone to meet in the middle. Joseph uses that shared skill to build a reading experience that works in a classroom and on a sofa.

Class runs through the book as texture, not slogan. The cramped flat, the stress that sticks to a kitchen, the phone close to running out of battery or data, the decision to buy a small treat and the second thoughts that follow, these are the places where English comedy has always done careful work. Only Fools and Horses found grace in tight money. The Office mapped the quiet tyrannies of work. Raymond Briggs honoured working class life by drawing it with respect for each chair and kettle. Joseph keeps to that measure. Money appears as everyday limits. The jokes happen inside those limits rather than above them. That is why the book binds rather than divides. People recognise the constraints and recognise the dignity in how the characters move through them.The anti racist work is similar in method. The book does not ask a reader to applaud a position. It builds a world in which racialised assumptions fail in the face of detail and in the face of competence. The cast is plural. Authority is tested in use. The weather of racism shows up as habit and as background and sometimes as a loud scene. I remember Joseph once asked me: 'Why is it Black Panther? Why not just Panther?' and he was grinning. The reply is to keep the room open and keep the story going. Joseph and Bircham are working from the inside and letting the joke carry the argument. The fun is the vehicle and the proof.

This is also a book about language. Joseph likes quick exchanges and knows how to place silence between them. He lets different voices share a panel and does not flatten them into a single register. He uses bleeped swearing as a timed beat, not as a scold. A throwaway vegan riff in the middle of a fight reads like a line you might hear on a real street where fear and humour meet. The rhythm feels natural because it is taken from speech. That rhythm is one of the things English comedy has always prized. Hancock’s Half Hour was about a voice that kept tripping over itself. Porridge earned its laughs by building scenes around small pauses and looks. Stewart Lee uses repetition and gaps to show a crowd how pressure works. Joseph brings those lessons into a book for young readers without turning the pages into a lecture about style.

As a former English teacher one thing I really like about the book is how good it will work in schools. Despite the best efforts of successive governments since Thatcher to ruin schools the best teachers still find ways to make the places hum with humour, surrealism, creativity and imagination. This book’s formal choices have practical uses in schools and homes. Short arcs will allow a teacher to work with a chapter in one lesson. Clear layouts help readers who are still learning how to track action across a page. The story carries enough hooks for work in history and media literacy and drama as well as English. A librarian can set up a group and let the readers lead because the book gives them the tools to describe what they see. A parent can read alongside a child and talk about a moment when a character tries and fails and tries again without losing face. English comedy has always turned shared viewing and listening into social glue. This book does the same for shared reading.

Place My Dad Fights Demons on the map with its older neighbours and the lines show themselves. The Beano and The Dandy supply the sense that mischief belongs to the public and that children are allowed to push back. Hogarth and Gillray supply the understanding that a picture can hold a policy up to view by giving it a face. Ealing supplies the belief that ordinary people are interesting enough to carry a plot. The class sketch from The Frost Report supplies the habit of turning a big concept into a scene that takes less than five minutes to play. Yes Minister supplies the training that institutions have their own momentum. Brass Eye supplies the insight that form and tone can be the trick, not just words and numbers. Dahl and Pullman supply the faith that a young reader can handle moral weight if you give them a good story. Briggs supplies the proof that drawings can hold grief and pride without speaking. Joseph and Bircham accept each of these gifts and then do their own job. They make a book that works right now and that will still be readable when the week’s headlines have faded.It also matters that the author has lived the culture he is helping to widen. Joseph comes from the zine tables and the small presses and the classrooms where comics were not a separate subject but a way to get a reluctant reader to turn a page and a way to help a shy pupil find a voice. He has written satire that bites and satire that hugs. He is serving a public role that asks him to think about libraries and access and how children read in the places where they actually live. You can feel that background in the poise of the book. It does not try to prove that comics count. It sets out to be something someone will actually read and share.

Return to the scenes that stick and you can see why it fits the English tradition so comfortably. The domestic embarrassment at the start tells the truth about family life with the lightest touch. The portal fight turns spectacle into a lesson about who pays attention and who shows up. The street reunion makes space for a joke that a ten year old will repeat and a line that a parent will remember when the house is loud and the day is long. Mr Mantrikz is foolish and he is also a father who is learning. Rye is serious and Rye is also a teenager who wants to laugh. The world is strange and it is also full of small tasks that cannot be ignored. The book lets all of that stand together without loss.The English tradition of humour does three things at once when it is healthy. It pricks snobbery and swagger. It keeps a door open to people who do not have much power. It protects the simple goods that make living together possible. My Dad Fights Demons does those three things with clarity and with heart. It gives readers a fresh set of lines and pictures to share when they want to say what matters. It offers teachers and parents a book that carries laughter and care in the same bag. It gives the larger tradition a new piece of evidence that jokes are not ornaments. They are a way a country keeps its wits. Joseph and Bircham have made a story that earns a place beside the earlier classics and that will send its readers back to them with better eyes. Fantastic.