Aristotle and Female Animals etc

Interview by Richard Marshall

' One idea that I think is salient about my work for modern philosophy is that it is often not a good idea to simplify the history of ideas in order to fit a modern agenda. If it did some good to vilify Aristotle, then maybe this was a necessary moment in the feminist dialectic with an intellectual tradition that was certainly largely pernicious to women. But getting things wrong and fundamentally wrong about philosophers’ views does not serve anyone’s interest and seriously undermines the credibility of those who do this. It takes away the richness of our intellectual traditions.'

' Aristotle does see a greater affinity between non-humans and humans than he is often given credit for. This is partly because his more popular and well-studied works, such as the Nicomachean Ethics and Politics, seek to find ways in which to describe what is distinctive about human nature, and so he is more apt to pass over the similarities. In his zoological works, however, he is keen to find the broader kind to which traits belong and so there are many abilities which we share with other living beings, including social emotions and social intelligence.'

'One thing to note is that Aristotle’s zoology is not motivated by direct self-interest; he does not study living beings in order to learn more about humans. The study of life is part of his philosophical programme to discover the true essences of things. This pursuit is driven by disinterested desire for knowledge for its own sake, just as one would study the stars and planets'

'I would not deny that Aristotle is sexist and he is even at times misogynist, but what I challenge is the presence of any systemic theory of female inferiority in his writing. Indeed, when you scrutinize his work rather than picking out juicy quotes, there is very little evidence for this.'

Sophia M Connell has recently published work on Aristotle’s nutritive soul and is developing a series of papers on the bodily basis for intellect in Aristotle’s philosophy. Another strand of her research makes relevant connections between Aristotle’s biology and his ethical and political works. Sophia has published several papers exploring these themes in Aristotle and contemporary Aristotelianism. As well as this, Sophia is developing new research on the female body in ancient philosophical and medico-philosophical texts.With relation to more recent history, Sophia is looking into the role of women in early analytic Philosophy.

Here she discusses the feminist case against Aristotle, the difference between male and female roles in reproduction in Aristotle, semen and menstrual blood, Aristotle's metaphysics of female matter, the role of the generative male, Aristotle’s theories regarding generation in lower animals like fish and bees, sexual differentiation, material necessity and deformity, teleology, the capacity for virtue in animals, Aristotle’s views about female animals and whether his views have currency now or are of just historical interest.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Sophia M Connell: I started off as a scientist but when I read the books of Geoffrey Lloyd on the origins of Western Science (e.g. G.E.R. Lloyd, Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, London: Chatto and Windus, 1970), I became fascinated by early Greek science and its philosophical basis. I changed courses from Biology to Philosophy but have always retained my interest in the way in which humans attempt to explain and theorise about the living natural world. I also have particular interests in empiricism and ethics in modern philosophy, and worked on Hume and feminism in my undergraduate degree. When I joined the Classics Faculty at the University of Cambridge for postgraduate study, Geoffrey Lloyd significantly shaped my interests, introducing me to Aristotelian biology and its cultural roots. He encouraged me to concentrate of one of the most maligned but also, I believe, one of the most philosophically rich of Aristotle’s works, On the Generation of Animals.

Over the years I have wondered (and worried) about whether I am actually ‘a philosopher’. The discipline makes it tough to be accepted and in so many ways I have never really fit the mould. But as I get older, I realise that I am so very suited to thinking in the way that philosophers do (to the irritation of my family no doubt). I love analysing and arguing and picking apart positions and assumptions; I am very grateful to be able to do what I love for a living.

3:16: You’re an Aristotelian expert and have written about his theory of reproduction. Now this area has been taken by some feminist readings to endorse a systematic and proto-scientific sexism. There seems on the surface plenty of evidence for this. Can you first say what has led feminists to see Aristotle as laying down the foundations for the predominance of misogynist societies across the world. What’s the case they make?

SC: Second wave feminism was often driven by the need to point out how systematic gender oppression is and was throughout history not only in institutions but also in culture. Why was it that even though women by the mid-20th century were not barred from education and employment, they continued to be economically, educationally and socially disadvantaged? The reason, they argued, was not biological but social and cultural: the patriarchy and patriarchal ideology surrounds us, keeping men and women in their designated places – as dominant and subservient. Simone De Beauvoir pointed to the myths that shape our consciousness, including Greek myths in which women are seen as weak, subjugated and morally suspect. And it is not only in stories that patriarchal ideological takes charge of our minds but also in other strains of thought, including philosophy itself. Philosophy has traditionally set the world out as objective, devising a theoretical understanding of reality and relations, which hide the biases on which they are based. Thus, we can find that Plato seeks the philosophical state of mind, and deems this to lack gender, when in fact he promotes a masculine ideology and suppresses the feminine.

The feminist case against Aristotle is much more complicated and rests in part on the idea that it is his worldview that underlies significant parts of our inherited metaphysics – with dichotomies such as nature and culture, active and passive, form and matter mapping directly onto our own idea of what counts as a man and what counts as a woman. This makes Aristotle the very originator of Western patriarchy ideology. Added to this, some feminists quote sayings out of context such as ‘female is (as it were) deformed males’ (leaving out the ‘as it were’, On the Generation of Animals [GA] IV.6, 775a16) and women lack an authoritative deliberative faculty (Politics [Pol.] I, 1260a14) or women are lying, scheming, more prone to tears (Historia Animalium [HA] VIII(IX).1, 608b9-14). All of these mentions of women or the female in general are taken from different works and no context is given. Thus, many of these ideas are misunderstood in terms of Aristotle’s philosophy.

I would not deny that Aristotle is sexist and he is even at times misogynist, but what I challenge is the presence of any systemic theory of female inferiority in his writing. Indeed, when you scrutinize his work rather than picking out juicy quotes, there is very little evidence for this. Indeed, he seems to have different things to say in different places and some of these are in tension. On the more positive side, he says that female animals are in general cleverer and have better memories than male animals (HA VIII(IX).1, 608a25-28, 608b10), that females who care for young are practically wise (phronimos) (HA VIII(IX).5), that women can and should be virtuous and that women have significant medical knowledge (HA IX(VII)). I am working on trying to make sense of these ideas, see for example this recent talk: ‘Aristotle on Women’ which was given at the Joint Session of the Aristotelian Society and Mind Associations in July 2020.

Aristotle does not write a treatise on women; and it is impossible to construct one because he refers to women or female animals in different places for different purposes. His views are often informed by his culture, which was one of the most patriarchal the world has known, and as an empiricist, the facts around him could not help but influence him. But this effect has been much exaggerated. Aristotle seldom just went along with the status quo; his struggles in the Politics are testament to this. One can understand his more disparaging comments in that work as a need to appeal to an audience that considers a wife to be a type of slave (Pol. I.2, 1252a1); he must argue that she is actually a citizen and capable of virtue and happiness.

3:16: But Aristotle does have different roles for the male and female doesn’t he? What are these different functions according to him? Is this part of what’s called the ‘seed’ theory?

SC: I have detailed a little already about the overall view of Aristotle as a misreading but will now give a brief outline of the specific part of that interpretation which deals with his theory of reproduction. As many critics note, Aristotle says that the female animal contributes material or matter (hulê) to the new embryo and that the male animal contributes the start of the motion or change (hê archê kinesêos). Whatever initiates the change which ends in a new animal can also be said, in some sense, to be the cause of the form coming to be in the mater. This is why some people use the shorthand that the male contributes the form, but this formulation has led to many significant misunderstandings of his theory and for this reason I resist that shorthand. Feminist critics emphasise that what the female contributes is ‘insignificant’ being ‘bare’ or ‘raw’ matter. This is incorrect in terms of Aristotle’s theory and his more general philosophy. We must take into account two things: the change that Aristotle’s is discussing in the Generation of Animals is the most complex change there is – a change from not-being to being a living substance. This change involves the meeting of an active with a passive potential for that result: it involves form gradually manifesting the full actuality of the kind in a matter that has been specially worked up by an animal with a nutritive soul the same in kind. The matter contributed is like no other matter in the fact that it is part of the blood of the female animal which has been refined and is ready to become all the living parts of an animal the same in form as that animal. This is not insignificant or raw at all.

On the first point, the female principle (not animal or woman) is the passive potential and the male principle (not animal or man) is the active potential for this substantial change; when they come together, these joint actualities are realised in one product. The female animal is not more material than the male or more passive – but her contribution to generation is both of these. Aristotle’s resists the idea that male and female contribute in a parallel manner to generation. For him, the process of change must map onto the teleological structure of the four causes. The male and female differentiate their roles, the male providing the start or impetus for this change, the female the appropriate materials prepared by her soul. He thinks that the male contributes nothing to the material; his seed dissolves and evaporates after its activity has been incorporated into the material. However, the idea that the female contributes nothing to the form or nothing formal to the embryo is not quite correct; she must be the same in form herself, thus her material contribution is aiming toward the same form as that of the male. It is part of the teleological ends of generation to be as it is. And on top of this, as the dynamic product of nourishment in her particular body, it has capacities to shape parts of the embryo’s body to be female and to resemble the mother.

3:16: Female semen and menstrual blood seem important in all this. How does Aristotle see them?

SC: Aristotle resists a bio-medical theory that was current in which women were thought to contribute semen just like male semen, literally ejaculated within the body at orgasm and menstrual blood which would serve as food of the embryo. He believed that this theory was unsupported by empirical evidence and, besides this, overdetermined. Since the opponents agree that women contribute menstrual blood, why should they posit that females also have semen? Women (and other female animals), for Aristotle, do not have semen like men but they do have ‘sperma’ – seed -- and this seed is actually their menstrual discharge, a more refined part of their internal nourishment, i.e. blood. When the body is well fed, some of the excess ‘useful’ nourishment overflows into their uterus where it awaits the addition of male semen. Together they will establish the new embryo as the active and passive potential for that change. The empirical evidence that tells against the opposing theory is that women can become pregnant even when they do not orgasm during intercourse with a man, which is of course true (On Generation of Animals I.19, 727a6-11).

3:16: How does this all fit into his ideas about a metaphysics of female matter?

SC: In terms of Aristotelian metaphysics, hylomorphic compounds are always closely matched. In artificial instances, the matter must be matched to the form – you cannot make a statue out of marshmallows, you need something that you can mould but which then holds its shape, such as marble or clay.

Matter and form in animals allow for less flexibility – you cannot make a fox out of anything but very specific fox matter; even dog matter won’t cut it. A male fox that mates with a female dog cannot establish any dog form in that matter; instead a mutant hybrid results (Generation of Animals II.4, 738b20-33). The matter involved cannot be just any old foxy matter, not paws and fur, but only the menstrual blood of a fox, poised to develop into an infant fox’s body.Matter and form in a fully formed animal must be matched to the form in a completely different manner, it must be the functional living parts. Matter will be that completely functional body and form the soul that expresses those functions. It is even possible to prize these two aspects apart? Some find this a challenge; and within the generative products of two separate parents, it is simplistic to think of the female matter as anything else but the living animal in potential – a potentially ensouled animal.

3:16: You reassess the role of the generative male as seen by Aristotle. So what does it mean to say that the male is the efficient and formal cause of generation?

SC: In arguing against those who think that male and female contribute parallel seeds, Aristotle seeks to establish that the part that the male plays in generation is different, acting as the proper efficient cause. The male principle initiates the complex patterns of change that will ultimately result in an animal the same in kind as the parents; the male animal ensures the advent of form in matter (GA II.1).

Aristotle posits that the male contributes nothing material to generation, something that Galen for one cannot understand. Why waste perfectly good material which can be used for bone or sinews? (Galen De Semine I). This thought would not make sense to Aristotle, because as efficient cause, the male role stands apart from matter. It must touch and affect the materials but is itself unaffected. This idea is quite odd and Aristotle, realizing this, attempts to solve a whole series of dilemmas (aporiai) concerning it (GA II.1-6). One difficulty is how it can be that, even though the male semen dissolves and evaporates after contract with the female contribution, it continues to influence development? Aristotle’s answer is to provide us with an analogous process – ‘it is like the automatic puppet’. Automatic puppets were probably toys which required one trigger in order to set off a series of responses, a dance, for example. If you think about it, this presents the male role as quite minimal compared to the female who has prepared the materials such that one push or trigger begins a series of complex changes which result in the formation of a new animal.

3:16: So how would you summarise the male role in Aristotle – and is this important in your push-back against the traditional feminist critique?

SC: The male is the initiator of the change that brings about a new animal; his role is as efficient cause of substantial generation. This role is also characterised by Aristotle as the active agency in generation (GA I.21, 729b9-19). What this means is that the change that results in the new animal occurs due to a combination of active and passive capacities to bring about that change – the male is the active capacity. Male animals when healthy must convey this capacity to a female who has in place the correct material seed (i.e. menstrual blood or its analogue); the most common way to do so is via semen deposited into the female’s body during copulation.

There are animals that do not have semen (insects); in these kinds, the male and female must stay together for a long time while the ‘principle’ (presumably the heart analogue) in the male brings about this effect on the female’s materials (GA I.21, 729b21-32). In these cases, it is the female who inserts something into the male to get her materials close to that principle. Other animals do not have penises and so must do what they can to get their semen into the female.

The pushback is that the male role is often exaggerated in two ways. First of all more is claimed for it than Aristotle actually says, for example that it is the principle of life itself, that it acts like god, or it contains rational soul.

Second, the way that Aristotle characterises the male principle, i.e. the causal principle in general, is transferred to the male animal, most often the male human being – thus, it is sometimes said that the men are active, women passive or that men are spiritual or intelligent (due to their generative role) while women are more bodily and unintelligent. There is no evidence for this in Aristotle’s biology. The evidence from his zoology and politics is mixed and confused; he says not only that women do not have an authoritative deliberative capacity but also that female animals are typically cleverer, easier to train and have a better memory than males. His zoological works point to female animals being more set up for intelligence and males for spiritedness, the basis of courage. In any case, these differences look to be side effects of hotter and colder bodies and not to be linked directly to any generative functioning.

3:16: How do Aristotle’s theories regarding generation in lower animals like fish and bees connect with his views about humans.

SC: One thing to note is that Aristotle’s zoology is not motivated by direct self-interest; he does not study living beings in order to learn more about humans. The study of life is part of his philosophical programme to discover the true essences of things. This pursuit is driven by disinterested desire for knowledge for its own sake, just as one would study the stars and planets (On the Parts of Animals [PA] I.5). Human beings desire to understand, to fulfil their own natures as thinking animals. Thus, he aims to understand generation and other living activities in the broadest range of living beings and is not focused on humans. Within the zoological writings, we find that Aristotle has a peculiar mix of methodologies with relation to lower animals. At times he focuses on human beings and tries to extrapolate from them to other species. Humans are the most complete and the most familiar animals (HA I.6, 491a19-23, PA II.10, 656a10, GA II.4, 737b25-7). So, for example, he takes all the bio-medical information he can get about menstruation and the working of the female body with respect to fertility and comes ups with a general theory of generation based around menstrual fluid as the female’s contribution, even though very few other animals are seen to menstruate (GA I.20, 728ab1-2).

On the other hand, Aristotle will sometimes use lower animals to prove a general point about his theory. So, for example, Aristotle believes that insects have a special way of mating, with the larger female inserting a part into the male, as I described earlier on. This is meant to prove one of the main tenets of his theory of reproduction which is that male animals do not contribute anything material to generation. In another instance, Aristotle wishes to show that female animals can ‘generate up to a point’ and uses eggs to explain this. Some females (mostly birds but also some fish) produce ‘wind’ eggs without a male animal being involved. These eggs have a certain differentiation and so show some sophistication but they never grow into an animal; thus the female cannot generate on its own since it lacks ‘the principle’ of soul – the efficient cause supplied by the male (on wind-eggs see S. M. Connell, ‘Nutritive and Sentient Soul in Aristotle’s Generation of Animals II.5’, Phronesis, 65/3, 2020: 324-354 and S. M. Connell ‘The Female Contribution to Generation and the Nutritive Soul in Aristotle’s Embryology’ in Roberto Lo Presti and Giouli Korobili (eds.) Nutrition and The Nutritive Soul in Aristotle and Aristotelianism, De Gruyter Topics in Ancient Philosophy series, 2020).

In other cases, ‘lower’ animals challenge his overall theory; for example, he is open to there being certain fish which reproduce parthenogenetically (GA II.5, 741a33-741b2; III.5, 755b22-4; HA IV.11, 538a20-1). He certainly doesn’t think that eels mate (741b1; having never been to the Sargasso sea). Furthermore, there are quite a few non-human that defy gender stereotypes. The ‘king’ bee has the mainly female tasks of staying inside and producing young (GA III.10, 760b8-18), female bears and lions are braver than their male counterparts (HA VIII(IX).1, 608a34), and some males care for offspring while the females disappear (e.g. the male glanis fish: HA VIII(IX).37, 621a21-36; modern zoology has found this to be real behavior in a kind now called ‘Aristotle’s Catfish’, sadly now an endangered species).

3:16: It’s a rather toxic issue for philosophy at the moment to talk about how many sexes there are! What would Aristotle say about sexual differentiation?

SC: For Aristotle, sex dichotomy is fundamental in the world. Taking the evidence from the animal kingdom, and particularly the land and sky dwelling kinds, he imputes two sexes to every living being, including plants. All living beings have the male and female in them, even if they reproduce on their own and there is no separation into token kinds (GA I.23). Sex is defined by reproductive function in this context. While he admits that some men are more feminine than others and some women more masculine, thus admitting a kind of scale of gender, which may also affect fertility (more feminine men and more masculine women are less fertile; GA II.7, 747a1-3), these seem to be descriptions based on cultural assumptions of male and female appearance and behavior rather than an acknowledgement of any biological fluidity of sex.

3:16: What was Aristotle’s dilemma regarding heredity and which interpretation do think is best to capture his views about hereditary?

SC: The dilemma is mostly in the mind of interpreters who focus on the male contributing “form” to generation in Aristotle’s theory, something that can be misleading if not properly understood to be part of a teleological process whereby the efficient (male) and material (female) causes aim for the same end. This idea that the male contributes form and the female matter can be simplified further by being mapped onto artifactual examples. If the female contributes bronze and the male the shape of the statue, then the female wouldn’t be able to contribute anything that affected the appearance of the statue; these specifications would come exclusively from the male. The solution to this seeming problem is to consider more closely Aristotle’s theory of nutritive contributions from both parents. The female animal’s contribution is blood that has been worked up by her soul to be ready to become all the parts of the body of this type of animal which will also be her particular son or daughter. Thus, it is not like homogenous bronze at all.

Furthermore, Aristotle’s idea of the “form” that the father is ultimately responsible for ensuring comes about in the matter, is a universal: horse, human, octopus, etc. It is does not mean that the male contributes every ‘formal’ feature to the young. This solution draws our attention away from form and matter to concentrate on the contributions of male and female animals as residual parts of the processes of internal nourishment, which lead to the functioning parts and the whole multifunctional body of the animal. Both male and female contributions will include ‘potentials’ (dunameis) related to their particular bodies, the shape of a nose for example. These potentials are actualized during the development of the embryo and are neither material nor formal.

3:16: What role does material necessity play in his biology and does it help explain things like infertility or deformity in Aristotle?

SC: By material necessity I take it that you mean the processes that occur without the guidance of an animal’s particular nature. Some of these are natural, since the interactions and motions of the elements are natural. But they are unnatural if they disrupt or interfere with the goals of an animal’s soul or life. Aristotle puts it this way: the things that are contrary to nature are in a way in accordance with nature (GA IV.4, 770b15-16). Since all animals are made up of materials and live in a constantly changing environment, they are always vulnerable to disruption both inside and out. Illnesses are a case in point: Aristotle is informed by medical theory and knows about the effects of diet and external factors in the health of all animals. It is also the case that all animals will eventually die and the way their nature controls this process is intriguing to him; each animal has a set life span and times when they become fertile and decline (HA VI.19-23; GA IV.10, 777a33-35); this is in their natures but related to the fact that they are imperfect as individuals. Their souls will become weak, their bodies will dry out and they will eventually have to give over their roles to the next generation. Sometimes there are errors or anomalies which can be explained by the pressures of material factors, both inside and outside the animal’s body. One way an animal can fail to fulfil its nature is by being unable to generate, i.e. by being or becoming infertile at a time when it should not be so. This can be caused by disruption during its development or by diet or disease (GA II.7). This is pretty straightforward in the case of blooded live-bearers like humans, dogs or horses. They will live out their own life but be unable to contribute to the continuation of their kind and so be a sort of failure to be a proper human, dog, horse, etc. Trickier cases are in the lower animals where there are certain types that are not able to reproduce at all (those that are spontaneously generated) or reproduce only something that is unlike the parent (an imperfect outcome of nature; GA I.21, 729b33, II.1, 733a2-b4). In these cases, perhaps the whole species is some kind of natural deformity or that this is just the way that they fulfil their kind and that this is necessary to fill in the whole of a possible scale of life. Certain deformities happen during the process of development due to coldness and fluidity. Others are more ‘natural’ because they happen so regularly and are incorporated into the animal’s formal nature, which is defective. This way of explaining differences between animals is perplexing, for example the idea that seal’s legs are naturally defective because they ought not to drag (HA I.1, 487b23-4).

There are some animals that are deformities not due to developmental processes or general ‘deformed’ nature but because they are not the product of mating between two animals of the same kind. All hybrids are infertile in the Aristotelian sense of being unable to reproduce another like the parent (GA IV.3, 767b7-8) – a hybrid produce offspring like itself because it is a product of two different parents; it cannot make that happen for its offspring. But there is one type of hybrid that cannot generate at all, the mule. Aristotle’s extended explanations of this make liberal use of natural facts such as the coldness or dryness of the mule’s body.

Deformities that occur during development might take all kinds of directions, but Aristotle tends to classify them into two categories: missing parts (or fused parts) and redundant parts (IV.4, 771a17-18). These cases seem to be due to deficient or excessive fluidity. When vital parts are missing the animal cannot survive. In other cases, they may well be born deformed. In his attempt to explain fusing and missing parts, Aristotle notes that this happens more often in some type of animals and so is related to the nature of the kind. For example, animals he calls ‘the many-toed’ have more frequent deformities of this kind because (1) they never complete their offspring, which are born unarticulated (2) they produce many offspring at one time. This means that fusing and lack of articulation can happen more easily (770a36-b5).

(For more on the subject of deformity, see S. M. Connell ‘Aristotle’s Explanations of Monstrous Births and Deformities in Generation of Animals 4.4’ in A. Falcon and D. Lefebvre (eds.) The Generation of Animals. Cambridge Critical Guide, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 207-223).

3:16: And what role has teleology in his biology?

SC: Teleology can mean so many different things. Let’s take it back to basics and say that in the study of natural living beings, Aristotle looks for processes and patterns that aim towards ‘ends’ – telei. He partly does so because of the very obvious drives we can observer in living beings to survive and perpetuate their kind into the future – nature clearly aims towards these general goals. But Aristotle is less interested in the general aims of some overarching nature as he is in how nature operates in each living being (e.g. GA V.8, 788b20-2; On the Progression of Animals 1, 704b11-17). Their individual natures (or souls) are organized around sets of goals which express their way of life. An eagle breeds, hunts, flies, grooms, socializes, mates, etc. in an eagle-like manner; through all of these interrelated activities it embodies its way of being, and this is what structures these activities into one ‘end’, the end of living life in that particular manner and doing this well. One way this helps Aristotle to organize his research is to talk about that ‘for the sake of which’ things are the way they are. He can thereby explain body parts and structures in terms of the way of life of the particular animal in question (PA I). Aristotle includes activities and characters into this way of organizing biological information, coming up with an early precursor to ethology (HA VII and VIII).

What he never properly developed was any ecological theory. Tending to take each animals in terms of its own ends and aims, he very seldom focused on the ways in which certain animals depend on others for food; thus, there is very little evidence of any overarching teleological structure to the natural world in Aristotle’s work. This left room for him to think about how animals respond to different environmental conditions (HA VII(VIII).28) and battle for resources (HA VIII(IX).1, 608b19f.), themes more familiar to evolutionary theory than to design.

3:16: In nurturing offspring Aristotle seems to believe that both animals and the human animal share nurturing values – natural values. So does Aristotle think animals are at some level ethical beings like humans – but humans bring a sense of reflection i.e. ‘what makes a good life’ which is the distinction between non-human animals and humans? I guess I’m wondering whether Aristotle saw a greater affinity between non-humans and humans than perhaps he’s been given credit for?

SC: Your question is very nicely worded. There would indeed seem to be some degree of a capacity for virtue in animals, what Aristotle terms ‘natural virtue’ (Nicomachean Ethics (EN) VI.13.1144b16-17). He describes how animals care for each other selflessly and feel empathetic emotions, ideas which some modern scientists regard as the origins of human morality. You are right that Aristotle does see a greater affinity between non-humans and humans than he is often given credit for. This is partly because his more popular and well-studied works, such as the Nicomachean Ethics and Politics, seek to find ways in which to describe what is distinctive about human nature, and so he is more apt to pass over the similarities. In his zoological works, however, he is keen to find the broader kind to which traits belong and so there are many abilities which we share with other living beings, including social emotions and social intelligence. The way in which human virtue differs does indeed have to do with a self-awareness or self-reflection that few animals show any degree of. For Aristotle, this is due to the capacity for reasoning in people combined with an ability to perceive right and wrong (Pol. I.1, 1253a16-17). Only humans have to actively engage in their own development by practicing the virtues and learning the reasons why what they do is right and good. Other animals only have ‘natural’ virtue which can misfire, like the loving mare that kills the foal because she has no milk to feed it (HA VIII(IX).4, 611a10). Human beings have an ability to see the bigger picture and make decisions that go against nature and habit for the sake of these reasons (Pol. VI.12, 1332b7-9). But the differences between human reason and the behaviours of animals is often exaggerated not just in Aristotle but also in modern zoology or ethology. If animals do not have emotions, feeling, empathy etc. it is not clear how we can say human do either. Human are, after all, animals and there is a more well understood continuity we now recognize in terms of evolution. On these issues, I find the approach of Mary Midgley particularly pertinent, who encourages us to stop focusing on an ideology of ‘us and them’ in animal studies. I believe that she largely follows Aristotelian zoology and ethology in his regard.

3:16: As a take home then, can you summarise for us how you see Aristotle’s views about female animals and how do you evaluate what he has to say from a contemporary perspective – are there things still salient in what he has to say or is it really only of historical interest?

SC: One idea that I think is salient about my work for modern philosophy is that it is often not a good idea to simplify the history of ideas in order to fit a modern agenda. If it did some good to vilify Aristotle, then maybe this was a necessary moment in the feminist dialectic with an intellectual tradition that was certainly largely pernicious to women. But getting things wrong and fundamentally wrong about philosophers’ views does not serve anyone’s interest and seriously undermines the credibility of those who do this. It takes away the richness of our intellectual traditions.

By dismissing Aristotle on women as completely pernicious we lose sight of the ways he resisted the status quo, such as pushing for men to listen to their wives in the Politics. We also are in danger of losing sight of those early feminist who could see the positive aspects of his account – and used these tensions in his thought for powerful critiques of their own culture’s assumptions. Lucrezia Marinella, for example, quite rightly noted that for Aristotle women are cooler than men and that being less ‘spirited’ they are less prone to anger and violence. As such, they will be better rulers and more virtuous (see e.g. Marguerite Deslauriers, ‘Marinella and her Interlocutors: hot blood, hot words, hot deeds,’ Philosophical Studies 1:13, DOI 10.1007/s11098-016-0730-3. ).

I am mainly interested in correcting the history of Aristotle but am also interested in how we read Aristotle now. It is no longer necessary to form any system from his treatises, which we must follow as our own. And thus, we can allow that he is a varied thinker, using different ideas and arguments in different places – in some we can find materials that may be useful to our current projects. I think that his views about the importance of socialization and early education are very pertinent – and an antidote to the extremes of modern individualism. For Aristotle, no human can exist without a human community: modern habits of mind make these truisms difficult to see and difficult to philosophize about ((On these issues, see S. M. Connell ‘Nurture and Parenting in Aristotelian Ethics’ Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Volume 119, Issue 2, July 2019: 179-200 and S. M. Connell ‘Aristotle for the Modern Ethicist’, Ancient Philosophy Today: Dialogoi, 1/2, 2019: 260-86).

I think that the nurture of small children and the continuation throughout life of meaningful friendships are fundamental goods that are very seldom noticed. Aristotle’s philosophy gives us materials to mark the incredibly complex constant, on-going intellectual work of bringing up the next generation and the friendships that hold the key to the well-being of individuals and communities worldwide, work which largely falls to women in most societies.

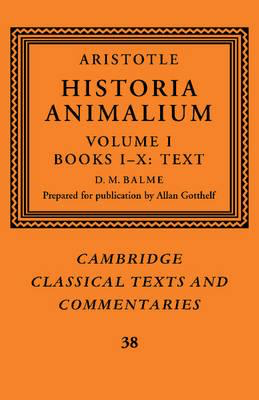

Aristotle can also provide us tools toward a better understanding of animal minds and emotions. His zoological writings, often so neglected in teaching and scholarship on the history of the subject, are for him a key part of his philosophical programme. In the Historia Animalium in particular, he documents the complexity of animal behaviours, attributing feelings, emotions and even thought patterns to many non-human animals. There is, for him, a continuum in living beings. Although humans can do things that no other animal can, Aristotelian gives us resources to value animal lives and experiences in their own right – each animal has its own way to flourish and its own goals. This is certainly a good place to go when thinking about environmental and animal ethics which are not merely anthropocentric and utilitarian.

3:16: And finally, are there five books you can recommend to the curious readers here at 3:16 that will take us further into your philosophical world?

SC:

1. Aristotle Historia Animalium (in three volumes, Loeb Classical Library) Of all the zoological works, it is perhaps this one that is the most misunderstood. Those who consider themselves proper scholars of Aristotle often think of the work mainly as a source of amusement. I would suggest a very serious reassessment of this attitude, one that has had a very powerful arguments on its side since at least the time of David Balme and taken up by Geoffrey Lloyd, Wolfang Kullmann, Pierre Pellegrin and most famously by Allan Gotthelf and James G. Lennox (starting with their jointly edited: Philosophical Issues in Aristotle’s Biology, Cambridge University Press, 1987). This is an extraordinary work of philosophical zoology – seeking the order of nature for the sake of the knowledge of essences with the ultimate aim of contemplation of truth. Such was Aristotle's motivation, which he obviously conveyed to devoted students who followed him particularly Theophrastus and Eudemus of Rhodes. Aristotle’s innovation in the study of living beings is truly extraordinary. The extent of his collection of data and his goals of systematic analysis would not be rivaled until the 19th century. Along with discovering ‘Aristotle’s catfish’ (Parasilurus aristotelis) and its unusual breeding behaviour, Aristotle explains that the octopus uses one of its tentacles as a penis (HA V.6, 541b8-12), a process only rediscovered in 1852 and now known as hectocotylization. He also recognizes a category of generative method – laying eggs that hatch internally before a subsequent live birth, having observed this in the “dogfish” (HA IV.10, 565b1-12). Again, the phenomenon was not properly documented until relatively recently (for more on Aristotle’s discoveries in zoology see Armand Leroi The Lagoon, Bloomsbury, 2014: 68-74).His animal investigations send long roots into many aspects of his philosophy, from ethics, where humans are understood to have features and capacities that overlap with other living beings, and are thought of as a sort of animal, to his metaphysics which focuses on processes and development very reminiscence of embryological development – the actualization of the potential for completion.

2.

Geoffrey Lloyd (1983) Science, Folklore and Ideology. Cambridge. Lloyd’s groundbreaking work on the life sciences in ancient Greece challenged the idea that ‘rational’ inquiry was completely separate from ‘popular and traditional patterns of thought’. There are many extraordinary revelations in the book such as the idea that philosophers were amongst a group of thinkers selling their wares in the intellectual marketplace. This is why they often exaggerate their own value and uniqueness. Lloyd brings the hustle and bustle of ancient debates vividly to life, partly through his expert knowledge of anthropology. The book includes commentary on texts that are still not fully incorporated into our understanding of early philosophy including ancient gynaecological works. Every subject he covers is an absolute gem, from ‘social behavior of animals in Aristotle’s zoology’ to ‘Aristotle on the difference between the sexes’.Lloyd was clearly very much ahead of his time – nobody has rivaled his account of Aristotle using human beings as a paradigm to think about other animals (I.3: ‘Man as Model’) or the way in which theoreticians gained much of their knowledge about gynaecology from women themselves (II.2 ‘The treatment of women in the Hippocratic corpus’).

3.

Mary Midgley (1979) Beast and Man. The Roots of Human Nature. London: Routledge.

I have only recently begun to appreciate how wide-reaching Mary Midgley’s philosophical perspective is. This amazing book takes seriously zoology and ethology in considering human beings place in the world. There are few books to rival this analysis even today. Midgley would go on to support animal rights but not from a cold, analytical perspective but from the conviction that animals are emotional and social, just as we are, and that we have deep and important relationship with other living beings which make our lives the human lives they are. In some places, Midgley shows that she has considered Aristotelian biological perspectives in her account. The most important of these is the fact that she thinks that human and non-human capacities overlap and that there isn’t a strict divide we can manufacture between ‘us and them’. To appreciate this is to understand Aristotle’s zoological writings and not stop at those that focus exclusively on human beings, such as his ethical and political writings.

Midgley’s work is ground-breaking in many extraordinary ways which have yet to be fully appreciated.

4.

Martha C. Nussbaum and Amelie Rorty (eds.) Essays on Aristotle’s Ethics. 1981.

I studied the Nicomachean Ethics under the superb guidance of Marguerite Deslauriers. That detailed tutorial class gave me much to mull over. For many many years, I continued to look back at her careful notes on every aspect of Aristotelian ethics probably the part that interested me most at that time was akrasia. This volume introduced me to the richness of Aristotle’s ethics. Almost every paper in this volume is still incredibly important to trying to get to grips with the complexity and brilliance of Aristotelian ethics and its relevance to us today. I briefly met both Amelie Rorty and Martha Nussbaum, both of whom did so much to help us to understanding Aristotelian ethics. I am often struck by how many of the truly outstanding scholars of Aristotle’s ethics happen to be female (see also Nussbaum’s Fragility of Goodness, 1986; Sarah Broadie’s Ethics with Aristotle, 1991 and Nancy Sherman’s The Fabric of Character, 1991).

5.

Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment (Unwin Hyman) 1990.

I was initially introduced to this book as an undergraduate. It is one of many extraordinary books by black American feminists that rightly reset the feminist agenda so as to be more inclusive. Although I love the powerful work of Audre Lorde and bell hooks, it is Hill Collins that I always come back to. She makes a case for reassessing what we consider to be intellectual thinking which is still so relevant. Through her, I have become most interested in women who have thought and challenged and argued but who do not fit a rigid definition of ‘intellectual’ or ‘philosopher’. I am finding in reading these thinkers that their perspectives are actually much more interesting and progressive than the reams of white men with University positions who existed at the same time. Russell, Moore and Wittgenstein were supremely privileged; it is not surprising that they could achieve what they did. But that is also only one sort of perspective; why do we assume that that is ‘proper’ philosophy and not the many other perspectives which are just as interesting and perhaps even more important for our times. I would consider, for example, the work of Zora Neale Hurston to be of philosophical importance; her ability to understand the communities of the South from the inside while assessing religion and morality is fascinating. At the moment, I am also thinking about Maria A. Stewart, who Hill Collins discusses, and her anti-slavery arguments. She wasn’t an acknowledged ‘philosopher’ because she was a black woman from a poor background without any formal education; what she could do was to give ‘sermons’ to other black people. Thankfully we have many of these preserved in writing; she argues not only for emancipation but is biting in her criticisms of the North for their continual oppression and abuse of blacks. She also extends her calls for a colour blind equality of humanity to gender differences, pointing out the domestic responsibilities that make women of colour so vulnerable. I am impressed by her thought that successful parenting is one of the most important of moral achievements, arguing that mothers in particular are crucial to the amelioration of society. Her arguments are powerful and important and need to be more widely considered as part of the history of philosophy, along with those of Sojourner Truth and Frances Harper from roughly the same period.If you are interested in her thought and where it came from and what happened next, an excellent place to start is Peter Adamson’s History of Philosophy without any Gaps Africana series of podcasts.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

NEW: Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

NEW: Joseph Mitterer's Beyond Philosophy serialised weekly