A Philosophy of Play (1): Bataille on Mr Nietzsche in "On Nietzsche"

Bataille is a writer who says he writes out of fear that he might go mad, and who confesses to an ardent aspiration that consumes him, an aspiration that cannot be translated into ordinary moral action or theological service, because it belongs to a region where obligation no longer commands, and where language itself loses its authority the moment it tries to persuade toward any useful end.

In the preface to his meditation on Mr Nietzsche, Bataille sketches a solitude that follows once one no longer serves the good or God, and he laments that Mr Nietzsche, who called for a new order of disciples, found only vulgar praise and misunderstanding, notably political misappropriations that he detested. He insists on separating Mr Nietzsche from party allegiance, from the coarser nationalisms and the antisemitic propaganda that disgusted him after his break with Wagner. This does not smooth the way for a philosophical treatise, it stages the risk of thinking that wants no reward, no later payoff, a risk that feels both like a mysterious bonfire and a dark vertigo at the edge of meaning. It is from this risky beginning that Bataille invites a reader to follow Mr Nietzsche into a territory beyond ordinary ends, a domain I identify as the terrain of play.

Bataille’s book appeared in French in the wake of a war that had already deformed Mr Nietzsche’s work through crude appropriations, and in a climate where a rescue of affirmation from propaganda had become an urgent task. Later translations widened the circle, yet the decisive point is the form, not the itinerary of editions. Bataille writes what amounts to an inner journal of risk and sobriety rather than a conventional commentary, because he holds that thinking is not exhausted by argument and that philosophy must sometimes take the form of an ordeal.

To grasp the stakes of that ordeal, it helps to keep in view several Nietzschean motifs . For Bataille the “will to power” names a dynamic of valuation and interpretation through which living beings seek to increase their strength not a simple doctrine of dominance. “Eternal return” is a thought experiment that asks whether one could affirm the exact recurrence of one’s life, down to every minor event, and so tests the depth of affirmation. “Transvaluation” calls for a revaluation of inherited morals that were forged under ressentiment, in favour of values born of strength, creation, and joy. “Perspectivism” denies any view from nowhere, proposing that every truth is encountered from within a life that interprets. Disputes trail each of these terms, but together they sketch a map adequate for reading Bataille’s wager.

Against this background Bataille reads Mr Nietzsche as the thinker of an experience that tries to be free from servile ends. Servility here is not an insult but a diagnosis of a habit that converts every intensity into a means for a later gain. In this light morality often looks like bookkeeping in guilt and debt, religion like an investment in transcendence with a promised return, politics like an accumulation of force to be repaid in victory. Bataille seeks an experience that interrupts this accounting. He speaks of sovereignty, not as the right to command others, but as the capacity to live moments that are not subordinated to utility. His sovereignty is a kind of inner freedom that shows itself in laughter, sacrifice, erotic intensity, poetic silence, or joyous waste, precisely where actions refuse to become stepping stones toward a programme. This Bataillean value does not appear where there is production or service, rather he insists some of the most human intensities happen in uselessness, where we lose time, laugh, or cry, or dance, or give what cannot be returned.

This reading converges with his idea of a general economy. Unlike a restricted economy that counts scarcity and utility, a general economy begins with excess. Life on earth, nourished by the sun, produces more energy than can be usefully channelled, therefore every society must dispose of surplus. The modes of disposal give shape to forms of life. One can waste it in catastrophic war, display it in luxury, burn it in communal feasts, gamble it, give it away in gifts that bind, or transmute it into art. Without confronting surplus we misunderstand desire and become prey to violent forms of disposal. Expenditure, for Bataille, means the release of energy without calculable return. The general economy is a lens rather than an equation, and through it he wants to show what the useful eye refuses to see, the sacred pull of useless intensity, the social need to squander rather than hoard.

Mr Nietzsche appears not as a prophet of crude power but as a teacher of affirmation, and Bataille’s response is to test whether one can affirm a life beyond ends. He recognises that such affirmation can be turned into a slogan by the worst politics, so he works on two fronts at once. On one front he refuses to reduce Mr Nietzsche to a partisan banner, just as Mr Nietzsche declined party service and rejected the nationalist propaganda of his time, including its disgusting antisemitism. On the other front he translates affirmation into inner experience rather than slogans, into practices that cannot be captured by propaganda because they are difficult, solitary, and often opaque to those who hunger for mottos. To read Bataille with care is to keep both fronts in view, otherwise Mr Nietzsche is either sanctified as a pure rebel or degraded into a motivational brand.

Because Bataille writes in a voice of risk and trembling, one might ask whether this is still philosophy or whether it belongs with literature or mysticism. His answer is that strict discursive reason is sometimes inadequate to the intensity it wants to show, and must borrow or invent forms. This is less an escape from reason, more a wager about form. If the object is inner experience at its limit, an experience that ruins projects and makes action lose its compass, then words that only argue a point are too stiff to do more than perform a kind of approach. The notion of limit experience is useful here, it names those passages in which a subject is pushed to a border where calculation gives way to exposure.

This search influenced later thinkers who found in Bataille and Blanchot not a system to build upon but practices that break systems open. With this in view the “will to chance”, the phrase that subtitles his book on Mr Nietzsche, can be heard as a correction to mastery. The will to chance reverses the need for control, it is a readiness to receive rather than to command, an openness to the unpredictable excess that mocks planning. As will to power discloses the living tendency to evaluate and to seek increase, will to chance prevents those evaluations from hardening into tyranny. Think of an artist who tries to command inspiration and ends by imitating her own earlier work, then imagine a turn toward risk, a welcome extended to what cannot be mastered, so that what arrives is not a plan but a gift. In this key eternal return becomes a test: could one will the return of what one did not control? If yes, affirmation ceases to be a fantasy of mastery and becomes readiness for what exceeds the self.

Bataille insists that this readiness carries ethical and political consequences, though they are indirect. Programmes that claim to serve humanity while reducing every moment to a means are suspect, as are pieties that demand sacrifice for transcendent ends and so subordinate living beings. In contrast he retrieves forms of sacrifice that are not servile, where destruction is not a payment for higher return but a disclosure of a sacred truth, namely that value can appear in useless expenditure. The communal festival, precious gift, even cultivated silence, these are foolish by ordinary, calculative standards, yet by Bataille’s measure they recall that a community is not only a machine bent on growth. There is of course a danger in this because cruelty can masquerade as sacred waste, and violence can borrow the language of excess. Hence the need for an inner test, a clarity that refuses to hide from its own darkness, a lucid confession that the path beyond ends is not a method for gaining power but a surrender of power at the very point where one is tempted to seize it. Laughter and tears in this serve as examples of useless intensity, both bordering on the sacred. Laughter shows a release from the grip of seriousness, and collapses the frame that turns the world into work. Tears show an exposure that cannot be priced, a flood at the limits of speech. Sacred does not mean anything religious here but is just any region in which exchange and calculation lose their authority.

Bataille writes to rehabilitate that region without reinstalling the theology that makes it a distant master. In Bataille religious words are turned against the structure of religion, not to destroy reverence but to free it from servitude. Communion then is not a prescribed sacrament, it is a description of moments in which beings share an intensity that refuses to be priced. There is a further worry that Bataille addresses in this domain, and that is considerations of transgression. Transgression can break oppressive forms, yet it can also become its own hollow ritual. Bataille knows this and applies discipline to his language. He refuses to make transgression into a badge of identity, which would be only another servile end, and treats it instead as a momentary breach that discloses the contingency of forms and the reality of excess.

Two errors are common. One is to imagine that any violation of norms is liberating, when violations can reproduce domination. The other is to imagine that a life of constant transgression is possible, whereas transgression is meaningful only against a background of form, just as laughter has sense only against the gravity that it interrupts. The counsel here is not hedonism without limit, it is the honouring of limits through learning how and when to suspend them, a matter of timing that amounts to a kind of wisdom. This bears on communication and community. If value can appear in useless expenditure, and if the highest intensities resist instrumentalisation, how can such experiences be shared. Bataille does not offer a community grounded in doctrine, he imagines bonds among those who risk together the suspension of ends. He is alert to the danger that such bonds can harden into a sect with sharp boundaries, the very opposite of what he seeks. The figure he prefers is that of friendships capable of remaining faithful to moments that cannot be converted into projects.

The point is not to produce a durable identity, it is to find words for experiences that have shaken one, and to accept that sometimes words will not come, in which case a silence can still be shared without feeling empty. This fragility partly explains his proximity to literature. Prose that is too clean risks neutrality, while intoxicated poetry risks confusion. He writes between them, with a prose that admits the failure to control what it seeks to show. That failure is a method rather than a defect. It resembles the diary form he adopts elsewhere, a form that accepts the contingency of days, changes of mood, and the fact that thought is a practice instead of a finished product. The diary receives rather than commands, which suits his devotion to chance. From this perspective the book does not promise a set of conclusions, it offers a stance, a way of standing at the limit, ready to be surprised, ready to lose.

It is also helpful to place his approach among other readers of Mr Nietzsche. Heidegger reads Mr Nietzsche as the culmination of metaphysics, Deleuze as a thinker of difference and affirmation. Bataille’s concern is different, he takes Mr Nietzsche as a guide for thinking about intensity among creatures who live amid production and war. The questions become whether sacred value can be found without returning to transcendence, and how to resist both piety and nihilism. This focus partly explains why his work matters for later thought that prizes limit experiences as tests of the boundaries of self and order, and what we mean by play. There’s an ethical worry that’s attached to this of course because a fascination with limits can turn away from suffering. Bataille insists that the exposure he seeks must include exposure to others, to their vulnerability and joy, otherwise sovereignty is only private intoxication.

Bataille of course was writing before recent Nietzschean scholarship firmly repositioned him as a naturalist. But it’s useful to understand that at the time of his writing about him Mr Nietzsche had become a magnet for clashing ideologies, many of them opportunistic and irresponsible. Bataille tries to strip away those uses, forgiving the misunderstandings of strong thinkers while condemning dishonest appropriations, above all those that fed nationalist violence. The climate of war and displacement also gives weight to acts of intellectual custodianship. Archives were endangered, manuscripts imperilled, and many depended on quiet guardians. Bataille’s appearance as custodian in such a context – he was a Parisian librarian - fits his valuation of useless care, a service with no hope of profit, an expenditure that preserves the possibility of thought. The question of practice follows. He addresses the daily temptation to convert every encounter into an investment, to turn poetry into an item of accomplishment, conversation into a tool for advantage, research into a tally of points. The claim isn’t that calculation can be banished, but that a life can make room for forms of harmless waste that confound calculation such as reading for no purpose, walking without counting steps, giving time without expectation of return. Such gestures are experiments in loosening the grip of calculated ends and small mimetic rehearsals of the sovereignty that attracts Bataille.

At the level of social theory the insight about surplus is sharp. Modern economies produce more than can be absorbed usefully, and disposal often takes violent or banal forms. Spectacles of consumption may distract from anxiety that could otherwise be addressed through shared projects, while the drive for endless growth periodically issues in destructions that are treated as accidents rather than as symptoms. For Bataille these are failures of imagination. A community that invents generous, non cruel forms of waste may blunt the push toward destructive waste. This is not a technocratic schedule but a moral anthropology that invites questions about whether festivals and arts are strong enough to absorb excess, or whether war and vanity have been given that task by default.

There are strong objections to this point of view. Celebration of uselessness can shade into negligence, rhetoric of sovereignty can romanticise privileges purchased by the labour of others, refusal of ends can become an elegant evasion. Bataille anticipates such charges without always satisfying them. He emphasises that the exposure he seeks is not a pleasure that floats above social realities, but a risk that includes shame, failure, and the loss of status. He does not want the strong to enjoy uselessness while the weak serve, he wants shared intensities that cross boundaries and unmake hierarchies, a comradely risk that resists stabilising itself as a class identity. Whether this sharing can be sustained is uncertain, but the orientation clarifies the aim of his language.

Responsibility is another concern. If one wills chance, has one not abandoned responsibility? The answer lies in a distinction between control and care. Responsibility need not mean control because sometimes care requires relinquishing control that harms what one wants to guard. The idea here is a practice that creates conditions for unplanned understanding rather than guaranteeing outcomes, a space in which not all good things are planned, and in which planning can choke the goods it seeks. Willed chance thus becomes a discipline of generosity. It also recasts the experiment of eternal return as a test of gratitude. Would one affirm the return of parts not scripted by the self, not as an acceptance of injustice, but as a measure of whether one’s yes to life exceeds the need to possess? In this register the will to power challenges the need to dominate and calls for transfiguration of strength into creation rather than control.

Mr Nietzsche’s fiercest words are read through this lightness, and Bataille’s pages read as a diary of trying and failing and trying again to live that courage. The lasting value of his On Nietzsche lies in a refusal of both piety and cynicism. Piety restores transcendence and obliges service to distant ends that swallow the present. Cynicism says that nothing matters and seeks private pleasures while shunning risk. Bataille says no to both, and his no becomes a yes to moments of intensity that neither serve nor negate, but reveal. He refuses to build a programme from those moments, because a programme would undo the lesson. Instead he writes narratives of failure and joy that neither deny nor capture what they describe. The awkwardness of his prose is the cost of fidelity to experiences that will not fit into the syntax of ends.

His suggestions based on all this are modest. Do not turn every poem into a task, do not turn every friendship into a ladder, do not turn every hour into an investment. Practise forms of generous waste that do no harm, cultivate attentiveness to others in ways that do not count, learn to laugh without spite and to weep without shame. These are not commandments but invitations to test whether a life contains moments one would affirm even if they returned forever, not because they serve some end but because they express. In that test the will to power becomes the will to create without owning, and the will to chance becomes the will to receive without hoarding. In this Bataille warns that the language of obligation is losing its hold, and that once that language is abandoned, freedom and loneliness arrive together. It recalls that Mr Nietzsche desired disciples yet found flatterers, that he was not a partisan mascot and that he rejected the coarse ideologies that later tried to wear his mask. To follow him is to enter a space in which ends fall away and an unpayable value appears, a value that cannot be secured, one that belongs to chance and to courage.

Bataille’s wager is that if one guards this appearance with care, without forcing it into a project, one may learn to live with a sovereignty that serves no master and harms no friend, and may discover in the very act of wasting, a use that rescues a life from servitude. He frames Mr Nietzsche through a sequence of refusals. First, a refusal of transcendence that still clings to adolescent immoralism. Second, a refusal of consolations that turn freedom into a new chain, and thirdly a refusal of piety that would greet the death of God with a shrine to the corpse. He speaks of laughter as immanent, not as a release purchased by belief, but as a power that breaks the hold of moral transcendence, and he draws an audacious equivalence, to choose evil is to choose freedom, by which he means to leave behind the childish habit of grounding responsibility in a beyond that finally commands and consoles.

In this he flexes the relation between freedom and disobedience, not to praise cruelty, but to show how often morality disguises dependence, how often the rejection of an external master is the first step toward hearing the affirmative yes that does not beg for permission. Bataille then writes himself into the scene and names the company he keeps. He lists writers who fail him for this task, and he returns to the one who says "we", Mr Nietzsche, whose voice meets him at the place where community flickers between possibility and failure. If there is no community, then Mr Nietzsche remains a philosopher, which here means a solitary intensity without an answering chorus. The remark cuts close to the wound.

Mr Nietzsche calls for a new order of companions, he speaks in the plural, yet he so often finds himself alone. Bataille adopts that solitude without pretending to repair it. He takes as his watchword a sentence he attributes to Mr Nietzsche’s notebooks, that if after the death of God we do not fashion a perpetual victory over ourselves, we will pay for that loss, and he moves from the sentence to its consequence, saying we can rely on nothing but ourselves which is an almost ludicrous responsibility that overwhelms and electrifies in the same breath. He admits the pull of rage, the enjoyment that violence promises, the pleasure of becoming a snarl of hatred, then he steps back to the tired body that writes and the fever that forces another kind of honesty. The chapter makes an interior meteorology visible, not to romanticise mood, but to show how philosophical sentences arrive like weather fronts and must be endured rather than calmly applied.

The figure of Mr Nietzsche hovers at the edge of dialogue. Bataille treats him as a companion and as a test, since companionship here is not comfort but exposure of a life to responsibilities it did not ask for, and of thought to intensities that it cannot master. When Mr Nietzsche says "we", Bataille hears an appeal to a community of those who would risk a sovereign experience without installing a new authority. If such a community exists, the word "we" is honest, if not, it remains a philosophical ambition. Bataille keeps this uncertainty alive. He probes the relation between a solitary voice and the plural it invokes, and it asks whether that plural will ever be more than a resonance in the throat of the one who speaks. The question is not settled, which is part of the integrity of the text. Bataille refuses to resolve the tension by inventing a fraternity that does not exist. He calls the bluff of voices that promise belonging while hiding the harsh fact that one must carry the weight of choice without divine or social guarantees. At the centre of this opening chapter stands the question of freedom without transcendence, a freedom that refuses to be paid for by a promised good beyond life.

The lines on laughter matter, because laughter names a rupture in the economy of seriousness that sets ends and rewards. It is a cry that comes from immanence, that is, from within life, and it is not licensed by an external court. In the same breath Bataille offers the provocation about evil and freedom, which is not an invitation to criminality but a rhetorical wrench that loosens the grip of moral bookkeeping. He wants to make visible an obvious but frightening truth, that the refusal of a transcendent law does not leave us lawless in the shallow sense, it leaves us with the more exacting demand to answer for our choices without appeal. Laughter is not an escape, it is a tangible sign that nothing outside will rescue us from the task of affirmation and refusal.

The issue of self responsibility returns in the form of measures to be taken responding to the demand that now falls on a life without guardians. This is not a stoic exercise – it is in fact be an antithesis of stoicism in many respects- but takes the form of a diary of a self that knows too well the desire to crush and to blame, and that claws its way back toward something like sobriety. Bataille refuses the heroic calm of a Stoic or ascetic. Rather he keeps company with temptation and weariness, and refuses any grand language regarding fate and affirmation that can be drafted into the service of a mood, or into the excuse that a violent world offers to a violent impulse. By admitting the desire to be a snarl of hatred, and by staging the admission in the same breath as the philosophical claim about responsibility, Bataille refuses the hypocrisy that separates doctrine from impulse. The doctrine must pass through the body that wants what it ought to refuse, otherwise the doctrine is pious noise. This is another crucial element of play.

Another scene of honesty arrives when he cites Mr Nietzsche’s desire to be taken for a fool rather than a saint, placing truth on the side of folly rather than sanctity. Bataille lingers on the ambiguity of masks, on the comedy by which truth speaks from behind a face that few will trust, and he lets the humour wheel slowly into a new uncertainty by asking, given Mr Nietzsche’s claim regarding foolishness, what do we really know about this Mr Nietzsche? Illness and silence surround Mr Nietzsche, disgust for the pious and for other targets besides, yet the distance remains and throughout Bataille keeps reminding us that the figure named Mr Nietzsche is both the author’s most intimate companion and a historical stranger whose body we do not and cannot possess. Intimacy here is a pact, and risky rather than a claim of knowledge. The pact states that to read Mr Nietzsche under the sign of the death of God requires a readiness to fail with him, not to win by quoting him, and that such failure is the only honest beginning for any we that would gather around this voice. Unlike our current secular philosophers of ethics who crowd the University departments and those outside the institutions who claim to have thrown off the superstitions of any belief in God Bataille realises that Mr Nietzsche’s most profound call is to realise that the death of God is the death of all values rooted in an unquestionable grounding.

The subtle core of Bataille is his understanding of this point and of the need for an ethics without edict. Therefeore Baitaille’s reader is not given a code. Instead there is a pedagogy of attention to moods, images, and involuntary motions by which a life reveals its dependence on guarantees. The images of a storm both internal and external Bataille summonses are there to loosen the idea that thought takes place in a protected chamber. The confession of rage is there to loosen the pretence that nihilism is just a proposition, and to show that the loss of metaphysical shelter rouses the animal in the human who mourns the death of God. Yet the remark about the ludicrous responsibility that overwhelms us is there to add the humour that prevents tragic posturing. Together they make a temper rather than a system, a way of refusing both hysteria and apathy, and of safeguarding the possibility of a sober affirmation that will not permit itself the comfort of a higher court.

This first chapter also gives a first shape to the idea of sovereignty that runs through Bataille’s work. Sovereignty is not a licence to command others, it is a momentary release from the grip of ends. In the imagery of this chapter sovereignty feels like standing during a storm without asking for the storm to justify itself, and feeling within oneself the stirrings that the storm names, without granting those stirrings authority. Mr Nietzsche is invoked as the one who supports this ordeal, because he has already imagined what responsibility looks like after the sky has emptied of gods. This support does not come as instruction, it comes as companionship, as the thin fact that there is another voice that says “we” at the edge of solitude. The plural does not guarantee a group, it gives courage to endure a moment without masters. There is a discreet politics in the way Bataille couples laughter, evil, and freedom. He refuses the standard moral hierarchies that demand obedience for the sake of order, not because order is always bad, but because order purchased by surrender to a remote authority is servile. He seeks an independence that is not arrogant, a strength that can admit its own worst impulses without becoming their servant, and a speech that can say “we” without lying about the degree of solitude it names.

This politics will later take explicit form when Bataille separates Nietzsche from nationalist and racist caricatures, but in Chapter 1 the political gesture is embryonic. It appears as a faithful reading of responsibility that neither flees to transcendence nor surrenders to resentment. It appears as hospitality to chance that will not abdicate care. It appears as a refusal to turn the name of Mr Nietzsche into a banner, since banners promise belonging and end by demanding obedience. This is why here I continue to use his stylistic quirk and preface the name of his predecessor with Mr. Mr Nietzsche is not the Nietzsche of the scholars or the many, many groups who continue to appropriate his name for their own ends as a sort of brand. The repeated attention to community, to that “we”, is not sentimental either. Bataille is wary of groups that promise communion and deliver conformity. The we he hears at the heart of Mr Nietzsche’s voice is a difficult bond, a bond among those who accept the disappearance of guarantees and yet continue to seek forms of shared intensity that will not be turned into projects. If the bond cannot be found, the text must remain philosophical, which is his way of saying that a solitary mind will keep the question alive, and will go on writing in the hope that speech might still reach an unknown companion.

Bataille is not ashamed of that hope, and it is not afraid to confess that hope sometimes evaporates. The honesty of that oscillation saves him from posturing. It leaves us with a practice rather than a result. Think of a relationship with someone whose love remains in the register of Bataillian play and escapes conformity, routinisation, convention and these controlling pressures that deform intimacies in the name of legibility. It is worth lingering on the way Bataille manages time. The storms do not pass like narrative episodes, they lodge within paragraphs as if to say that thought is weathered more than it is advanced. The present swells with remnants of earlier tempests and the anticipation of later ones. This temporality suits the claim about responsibility, since a life cannot put itself right once and for all. It must face the recurrence of the desire to blame, the recurrence of the wish for a master, the recurrence of the enjoyment that cruelty offers. Sovereignty is not a state, it is an event that must be risked again and again, and this is why laughter matters, because it punctures the solemnity that pretends to have solved what can only be endured and answered in the present tense. Near the end of this opening chapter the tone narrows and darkens, and a small arithmetic appears: there are so few of us. The sentence is almost nothing, yet it carries the weight of the project. It refuses crowd romance. It names a poverty of companions without despairing. It takes the “we” at face value and measures it. The count is not stable, because the book itself may gather more voices into that “we”, and because the act of reading can thicken thin companionship into something like community. But the count is also a warning.

The path beyond transcendence and servile ends is not an easy gathering place, and those who seek mastery will always prefer banners and systems to the discipline of risk and confession because with them come the promise of crowds who will be joined. What the first chapter gives, then, is a set of coordinates for living without recourse to the old securities, and a promise that such life, if it finds companionship, will neither be a sect nor a movement. It insists that remarking on the disappearance of God is not enough, that one must fashion new victories over oneself or else pay by sinking into resentful nostalgia. It keeps passion visible, not as romance but as pressure within sentences, so that thought has a visceral pulse. It names a laughter that frees because it belongs to immanence, and it touches the temptation to call evil what is simply disobedience to a vanished law. It does not deny the pull of violence that accompanies this freedom, and it does not soothe this with false remedies.

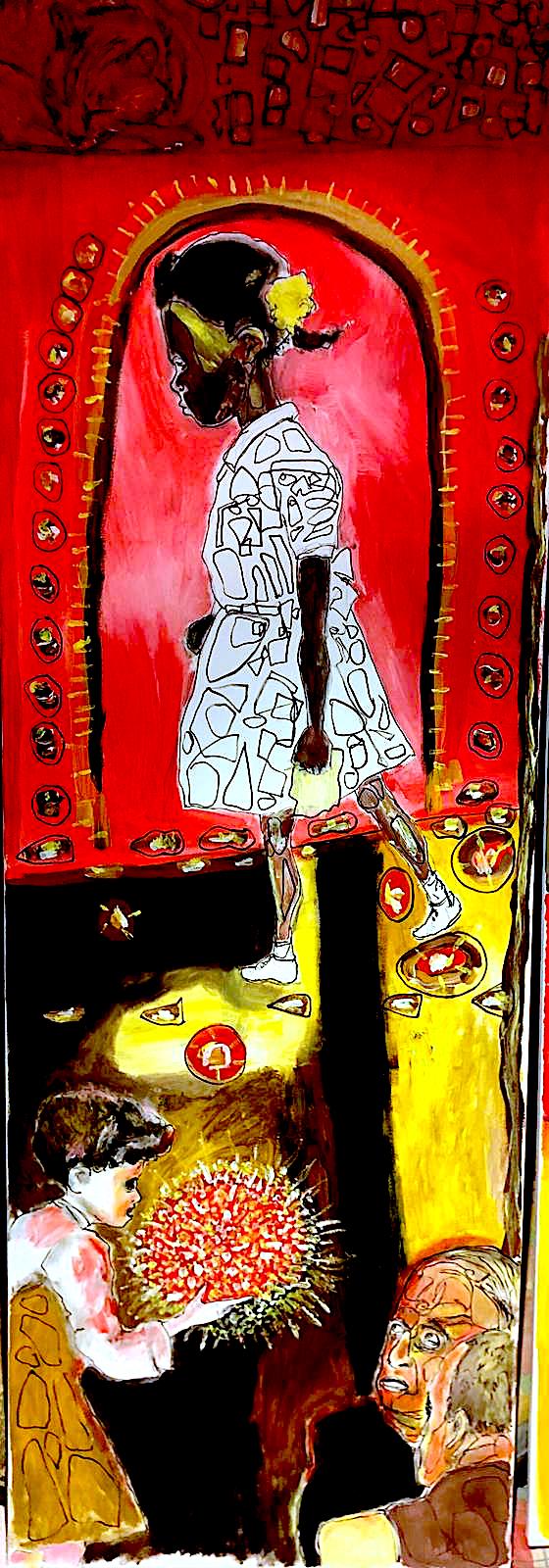

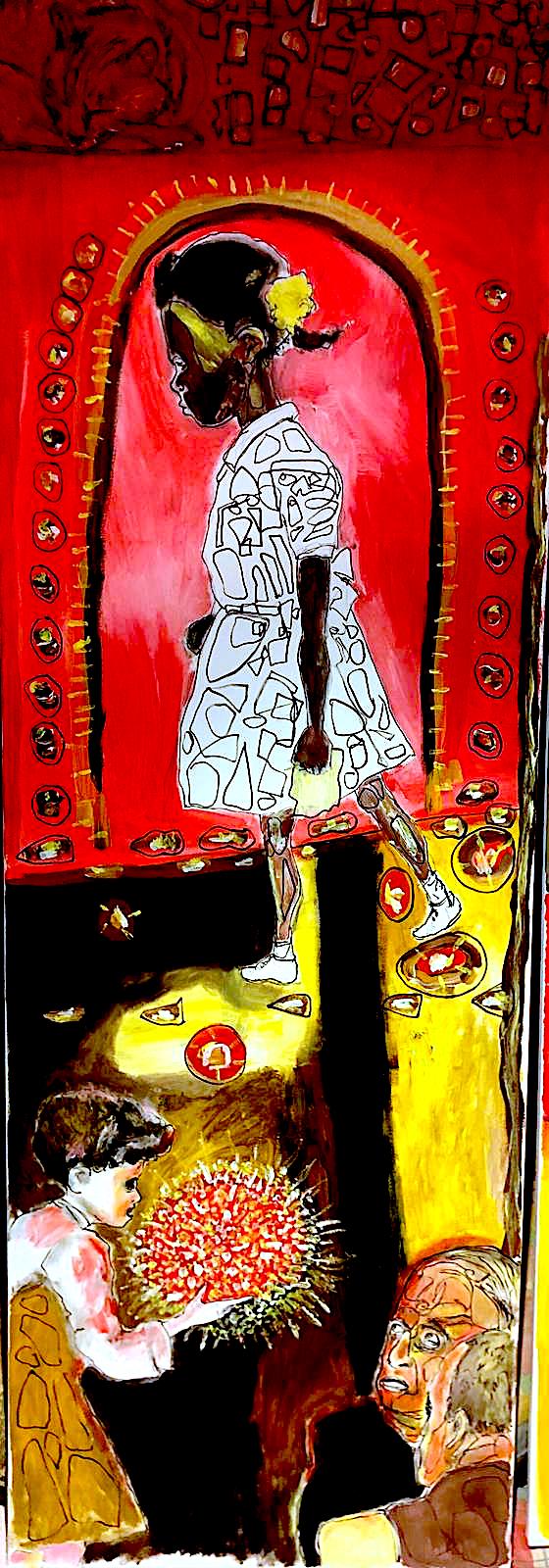

Bataille offers the humility of a voice that would rather be taken for a fool than a saint, and it offers a “we” that tests itself against solitude rather than pretending it is already a congregation, or ever will be. A long horizon unfolds, one that is more like Casper David Friederich’s intense painting of the monk on the beach I stood before for hours on the one occasion I was in Berlin. It is no accident that Casper David Friedrich’s painting of two men staring at the moon was the template for Beckett’s mis en scene for Waiting for Godot and that Beckett and Bataille were acquaintances by 1951.

In this manner chapter1 clears a place for the later diary, where the weather of a thinking life can be entered day by day, and where the will to chance will be exercised without forgetting care. The chapter ends as it begins, with Mr Nietzsche as a mask for intimacy, a way of getting close to a fire that has to be approached and survived, and with the sense that the only honest tribute is to let that fire alter one’s breath rather than to hold it up as a torch parade. In the next chapter moves from considerations of good and evil to a new hinge, that of summit and the decline.

Bataille alters the topography of ethics and morality. He proposes that what has been called good and evil must be seen in relation to being itself, to how beings conserve or expend themselves, and then he reframes the axis. The summit names the moments of exuberant intensity, of overflowing force, of expenditure without reserve. The decline names the intervals of fatigue and conservation, where rules gather around the care of life and its continued enrichment. Good and evil do not vanish, they are displaced by a more basic contrast between an apex of tragic intensity and a prudence oriented to survival. The moral tale becomes a dynamic between the glory of waste and the caution of a sort of costive possession.

This redrawing explains why Christ crucified appears here as the most equivocal of symbols. The scene is saturated with the language of crime and the largest imaginable sin within the Western Christianised culture – and remember that Mr Nietzsche’s complaint is that even those who claim to have rejected this culture have merely internalised it as free conscience and so remain within its grip - yet for Bataille the figure on the cross also condenses the extreme of sovereign expenditure, a life given to the point where calculation collapses. The paradox is not a church doctrine but an anthropological and naturalistic measure of how human beings invest meaning in destruction and loss. The cross becomes at once an indictment and a summit, a spectacle in which the worst act, the killing of God, appears as the passage through which the highest intensity is disclosed.

The text insists that the execution attacks the very being of God, then turns the knife by asking who is the agent of such an act, the named executioners, or the infinite crime through which all are implicated. The answer does not offer absolution, it exposes a logic of sacrificial value at the heart of moral feeling, and prepares a shift from moral arithmetic to the economy of sacred excess. The summit, in this sense, is a point where life itself spends beyond its safety and discovers an intensity that cannot be reduced to reward. Here Bataille repeats his basic claim with sharper teeth, that the significant peaks of experience are not means to any later good, they are consummations.

The decline by contrast is the rationalising wisdom of keeping and care, where beings protect their integrity and extend their powers through rules and routines. Between these tempos morality becomes visible as a pendulum rather than a code, sometimes answered by the laughter of immanence when rules are shown to be nothing more than instruments of conservation – what I’m calling play - sometimes answered by the sober breath that remembers fragility. The point is not to despise either . It is to understand why the highest values do not belong to thrift alone. In this movement play is give ethical weight and equal value.

Because Bataille speaks this way about peaks and endings, it risks being misheard as being a hymn to cruelty. Bataille anticipates that risk. He admits that the summit stands nearer to what is conventionally called evil than to the respectable good, since at the peak integrity is violated, boundaries are crossed, and the expenditure of force ignores the plea of conservation. But what matters is not the cruelty that copies power, it is the clarity by which an overflowing life refuses to become the servant of its own future. The summit is not the right to harm, it is the event in which the worth of a life appears in useless radiance. The decline is not a fall into baseness, it is a necessary time in which care becomes law. Between them a wise life would learn the timings of the pendulum arc between summit and decline. To do this would be to inbibe a rythem of life rather than come to understand it as a system.

Bataille then turns to a grammar of chance and play. If the summit is an event of overflowing immanence, it cannot be planned like a project. It comes as luck, not as a result of management. Bataille draws a hard line between speculation and the stake. Speculation subordinates the present to a calculated gain, limits risk, and seeks assured profit. The stake, by contrast, is the throw that risks what it has without the guarantee of a later return. He repeats an old preference in a new idiom, that the movements which exceed the limits of being take the form of a game that opens time rather than closes it, a will to chance that refuses to own the future in advance. This is why the summit cannot be chased like a career, it must be received as a gift that breaks planning, even when one has laboured to be ready.

This distinction illuminates an ambiguity in our ordinary talk about responsibility. The one who speculates can claim to be responsible, since nothing is left to hazard. But for Bataille that very hunger to guarantee outcomes can become hostile to life. Responsibility is not control, it is a form of care that sometimes requires relinquishing control where control would stifle what is alive. The will to chance is therefore not a childish surrender, it is a wager that accepts risk as the medium of creation. In this play the present is not consumed by a future that repeats the past, the present opens toward a time that does not yet exist, and in that opening the action exceeds the limits of being. The image of dice returns, but now the throw is not a metaphor of fate, it is a way of living that refuses to reduce every choice to an investment. Here lies a distinction between play in the Bataillean sense, and games. So long as games are played without the will to chance throughout then games are no less costive and investment orientated than any other activity. Of course within such a game there can be moments that open towards a time that does not yet exist, a playfulness that seems to ignore any sense of purpose delineated by the rules of the game. Play proper only does that.

Placed against the larger arc of Bataille’s thought, Chapter 2 tracks the passage from transcendence to immanence with more precise steps. The summit belongs to immanence, which he insists is something received, not a product of seeking. He is careful here, because he has watched how spiritual peaks are claimed by religious ideologies that attribute them to an external beyond, and by ambitious minds that make them into projects. He counters both by describing the summit as an immediate ruin of the self as a fixed being, and as a spiritual crest that cannot be held. One does not ascend by method, one is taken, and the only honest preparation is a loosening of the habits that hold the present hostage to a future profit. This guard against method is a guard against pride, since nothing here is a possession.

The decline is not dismissed by Bataille. It provides the soil in which any future summit might grow. It teaches patience, prudence, and the limits within which common life is not torn to pieces. Bataille just refuses to make it sovereign. He suggests that when decline attempts to seize sovereignty, when conservation and possession claims the throne of value, communities begin to worship survival as an ultimate end, and then the worst violences are authorised in the name of continued life. It is a bitter irony of modern times that murderous projects are justified as the safeguarding of being. The Bataillean counterweight, is play, a measure by which the most worthy moments are not those that secure the future at any cost, but those that let value appear without price. This is why the symbol of the cross is admitted in full ambiguity. It gathers cruelty, crime, and universal implication, yet it also manifests how a culture invests destruction with meaning that exceeds any ledger of use. In this Bataille retrieves the economy of expenditure that theology once carried. He can therefore take the cross as a summit without bowing to a transcendent command in any form.

The same holds for his other figures, festival and gift, laughter and tears, erotic waste and poetic silence. Each is a crest in which beings stop conserving themselves for a purpose and find themselves dissolved and remade by a value that cannot be earned. The political danger remains, since such crests can be conscripted by propaganda. Bataille knows this, so he keeps the language of risk in play, a reminder that these moments cannot become a party platform or communitarian project or plan without being falsified. There is a quiet confession tucked inside the chapter, that the path from decay to simplicity was a slow conversion from fascination with sordid extremity toward a cleaner sovereignty. Bataille writes that earlier he was magnetised by the turbid, by the scenes where decadence is dressed as grandeur, by the hard glamour of command. He names this frankly as a pact with a transcendent negation, the old pride of nothingness wearing the costume of strength.

The second part, he says, is an effort to clarify this temptation and to distinguish the proud hostility to reason from the sober refusal of calculation. The point is not to scorn reason like a child, it is to expose how reason, when it becomes a bookkeeper of being, will always resent the peak it cannot own. He then returns to movement rather than doctrine. If the summit flees those who hunt it as an object, one can still discover in oneself a motion that keeps drawing closer to it. One can make of a life a long divination of the possible, in which time itself enters, sometimes as abandonment forced by pain, sometimes as the ordinary thread of speculation broken by a sudden opening. To act is often to sow for a later harvest, and there is nothing evil in that. But there is also an action that places the present at stake for an unknown future, there is a throw that aims beyond the limits of being, and it is here that the will to chance becomes a practice rather than a slogan. Between summit and decline a life learns how to hold both, it keeps the common care that protects beings, while leaving a path in the heart where the useless and sacred crest can arrive unannounced.

The diary begins by naming a mystical state as a new feeling of power, and by insisting that the clearest rationalism can serve as a path to it. The tone is sober rather than ecstatic. It is as if reason, when pressed to its limit, ceases to police experience and starts to lead it toward a crest where calculation gives way to gift. Early entries weave Mr Nietzsche’s laughter into this ascent, not as a trivial mood but as the sign that tragedy returns to the comedy of existence once teleological masters lose command. The laughter is not trivial because it marks the passage from duty to affirmation, and it salts the entries with a refusal of pious gravity that would claim authority over what is given in immanence.

Desire enters the discussion. There is a confession that lovemaking has been associated with integral disrespect, with a radical rejection of whatever constrains inner freedom. The phrase is uncomfortable on purpose, since the disrespect is aimed at the economy of moral constraint that treats bodies as instruments of a higher end. From this refusal there appears what he calls an object without an objective, compared to the smile or transparency of a beloved, something that flees at the instant of possession. The diary does not turn this vanishing into a complaint. It takes it as proof that the highest value cannot be owned, that the summit, if it appears, appears only as a passing clarity that tears and heals at once.

The entries gather fragments. At one point there is a memory of Picasso’s Demoiselles and a store window dummy fashioned from a horse’s skull. Five months of nightmare are said to end in a carnival, a sentence that shows how terror can pivot into play without changing its intensity. The same pages stage the awkwardness of conviviality with famous companions, there is talk of fraternising with Sartre and Camus in a voice that calls itself childish for doing so. Zen monks appear as an image of austerity that cannot entice because they do not dance, drink, or enjoy in the way that this writing honours, which is to say without instrumental ends. The diary keeps its grip on the claim that joy must not be corrupted by the demand to serve a programme. A long meditation follows on whether the destruction of morality is itself a sign of strength. It is argued that those who inherit a grave moral history carry in their blood a seriousness that can be turned to a voyage without shores. The old soil, having given strength, can no longer hold those who have learned from it. There is a declaration that it is better to perish than to become weak and vicious, and a call to take a chance, to risk oneself on open seas where the suns of the past have set.

The emphasis falls on a confidence that is stronger than negation, a willingness to be conquered by what is not yet known rather than to fall back into resentful conservation. These lines do not ask for heroism, they ask for a posture that welcomes the future without demanding that it pay tribute to the past. The ethical thread is constant. Responsibility is not control, the diary keeps repeating, and that care sometimes requires the relinquishment of control. The mystical state is glossed as a desire to give rather than to take, a counter reading of power as generosity rather than domination. Extreme states are said to escape the control of the will, and speech that would do justice to them would need to alter human nature itself, which is a way of admitting that philosophy needs to back away from its temptation to define in lucid prose. Bataille uses the stammer as philosophy’s appropriate form when discussing play, a stammer without shame, that exposes the impotence of language standing before the crest that eludes capture.

The diary reminds us of Bataille’s context whilst writing the book. The Second World War was ending. As the diary moves toward the summer, the war enters with an intimacy that is difficult to bear. The pages record crowds with flags and flowers, children lifted onto tanks, smoke from bombardment, a village in flames near Melun, a volcano in the distance, planes swooping on a column, columns of smoke rising. There is a scene of a collaborationist paraded on a truck that resembles an execution cart, an image that disgusts the writer because it repeats the theatre of punishment rather than the clarity of justice. The account is an inner seismograph registering how public violence reverberates through a mind that has been trained to treat cruelty as a temptation rather than a solution. These scenes sharpen a political distinction that runs through the last entries.

Fascism is read as a national transcendence, powerful because it binds itself to a particularity that cannot become universal. Transcendence in this sense is a collective posture that elevates a nation above immanence and tries to impose that elevation on others. The counter movement gathers within immanence, where greater forces are mobilised against the illusion of an isolated above. The writing insists that the only transcendence still available is one that cancels itself by falling back into immanence, that is, a momentary lifting that refuses to claim authority. This analysis refuses both resignation and heroic pride, since it calls for an action that remains among others, and that will not crown itself with moral sublimity.

At the heart of the August pages there is an admission that lying has become our truth. The lie of transcendence is said to stifle, the lie of living is said to make dying less sad, the lie of love is said to make losing the beloved more terrible. The language of the lie here does not serve cynicism. It marks a recognition that projection, which is to say the overlay of images on life, cannot be abolished by a single decision. Even when the deception is seen through, attachment does not vanish, separation does not ease. The diary treats this as an ordeal in which lucidity and helplessness must be suffered together, without consoling dogma and without the pretence that clarity removes pain.

He writes that his place is not with those who teach. The explanation that follows makes the sentence heavier. What he writes is exact rather than ornate, because it names the delay between a thought and its consequences in a self that has been torn by war and by the collapse of guarantees. If a community can be found after calamity, it is found with caution, as faces regain their light and laughter returns like a rehearsal, not as a festival that pretends nothing was lost. This is what the diary does with the word “freedom”, which appears like a common light, yet requires a tenderness of approach that refuses triumphalism. Images of immanence close the section. There is a claim that upon reaching immanence we leave the stage of the masters, a formulation that condenses the entire work. To leave the stage of masters is to stop acting for spectators, to stop seeking applause from judges, and to discover a ground where value appears without being commanded. In these pages immanence does not mean a closed world, it means a world without a sovereign above, a world in which peaks occur as events rather than as privileges of contract.

The diary takes care to say that even here strength is needed, not to dominate but to resist the fall back into rhetoric. This strength is modest and alert, it belongs to those who keep their eyes open when others would prefer a banner. What this chapter adds to the earlier parts is a cadence. Fragments thicken into a daily practice, and the high conceptual contrasts of summit and decline are tested against weather, fatigue, erotic joy, disgust, and civic fear. The will to chance here is a discipline of risking the present without making it a coin for the future. The entries keep risking speech that might fail, and they keep refusing the mastery that would turn failure into a badge. The tone is sometimes tender, sometimes severe, often embarrassed by its own intensity. The embarrassment functions as a brake on vanity, a way to avoid turning a diary into a spectacle. In this sense the chapter is faithful to the thought that the highest moments arrive when ends fall away. It does not try to summon those moments, it arranges a life so they can visit, and it keeps a record of their departures without complaint.

The most striking achievement lies in how the writing holds love and war in one field without letting either cancel the other. The transparency of a beloved that flees at the instant of possession belongs to the same page as the smoke rising from a distant column. The first teaches that what we most want cannot be held, the second teaches that what we most fear cannot be banished by purity. Together they force a humility that neither stoops to piety nor hardens into cruelty. The diary calls that humility a way through immanence, and it takes the word freedom into its keeping as a light that guides without commanding, which is to say as a promise that belongs to the present rather than to an empire of ends.

He gathers these threads into a final weave, not with a triumphant knot but with the quiet pressure of a hand that has learned how to hold without grasping. What began as a refusal of servile ends and a wager on immanence ripens into an image of play, the child who says yes, and an epilogue that lets war, laughter and philosophy pass through one another until doctrines fall away and an exposed clarity remains. Mr Nietzsche’s figures return in a new light, the lion of will to power and the child of play, and Bataille hears in that child the tone of the will to chance, a readiness for creation that does not pose as mastery. The child names innocence, forgetfulness, beginning again, a wheel that turns upon itself, a sacred yes, and it corrects the heroic misreading of strength by returning strength to lightness.

In that turn Bataille draws near to what he has been circling all along, the small surplus that gives the world its light, the almost nothing that outweighs what is most important by accounting standards. Late in the diary he writes the sentence that crystallises the passage, upon reaching immanence our life leaves the stage of the masters, and with that the book tilts decisively toward a sovereignty that is not a throne but an event that visits those who have stopped counting. Bataille does not romanticise the peak. He insists that the summit is received, not manufactured, and that the sign of its arrival is simplicity rather than grandeur. Inmanence is not a rarefied height above the world, it is the world seen without the theatre of ends, tragedy braided with madcap humour, calm with a pulse. The laughter that haunted the earlier pages returns here as something deeper than mood, a measure of how far the rhetoric of transcendence has loosened its hold. Once the old serious masters have lost their authority, seriousness itself does not need to vanish, it changes tone, it gives way to a patience that can wait for moments that cannot be engineered. That patience is already a kind of play. It keeps the present open to what exceeds it, and it learns the grammar of risk without turning risk into glamour.

From this vantage the will to power is not abandoned, it is refined. If the lion roars against the idols, the child invents a game that no longer cares to smash them, because smashing and venerating are the same game when seriousness rules. The child’s game opens time, it does not repeat a script, and so it dwells nearer to chance than to conquest. Bataille writes that the state of immanence implies a complete staking of oneself such that only an event independent of the will can dispose of a being so far, which is his way of binding courage to reception.

Sovereignty then is courage without possession. It arrives when one ceases to treat experience as a tool and allows life to be altered by what cannot be ordered. The gain is paradoxical, a freedom that feels less like command than like generosity, a power that gives rather than takes, an ardour that does not enlist itself in any cause. The epilogue makes these claims answerable to the world by dragging them through smoke.

There is a page of August where sky and steel contest one another, a train of oil and petrol struck by low flying planes, black columns of smoke rising like a new weather, enormous insects streaking above roofs, spectators trembling and marvelling, then thinking of victims, then falling back into the strange neutrality that crowds adopt when danger passes them by. It is a scene without sermons, yet it lets the earlier opposition flash with literal force. The war appears as a struggle of transcendence against immanence, nationalism as a posture that elevates a particular above the field of life and tries to impose that elevation as destiny, and the counterforce as a gathering of immanent powers that annul the illusion by degrees, often slowly, often at terrible cost. The passage does not invite a moral of comfort. It says only that the theatre of transcendence has become comic, that the old lordly talk of noble existence and clean decision is now a costume for vanity, that the very attempt to stand above others turns into a risible spectacle in the light of a sky which no longer acknowledges masters.

This comedy is clarity that survives grief. The short tragedy has always ended by serving the eternal comedy of existence, Mr Nietzsche wrote, and Bataille repeats the line with an ache that does not diminish its truth. When he invokes Hegel’s owl of Minerva he does so to rebuke a wisdom that arrives only to mock the fallen, clear perhaps, yet shabby if it refuses the tenderness that immanence requires. The laughter he means is not the laughter of contempt, it is the breath that returns when fear loosens, the sign that metaphysical pomp has been seen through and that life will not be measured only by victory and loss. The scene with planes and the later admissions about waiting, explosions at night, a child crying somewhere outside the frame, keep this laughter from hardening into pose. It is the comedy of survival, not the comedy of superiority. In his most intimate pages he turns the great contrasts into social tact. Bataille says that to transcend the mass now would be like spitting upward, the spittle falling back upon one’s own face, and he stakes his measure not in a lofty vantage but at the level of speaking with a worker, the feeling of being a wave among waters. He does not pretend to erase difference, he speaks instead of a sympathy within immanence that marks one’s place in the world without making of place a pedestal. The bourgeois gesture of climbing on one another appears as a doomed commitment to exteriority, a frantic transcendence that forgets how to breathe.

The danger is symmetrical, he concedes, the day the bourgeois order is destroyed it would still be possible for immanence to empty itself into monotonous reproduction, a mass without history or difference. The warning is aimless without the discipline of play. Only if immanence remains lively as experiment, only if it keeps open a path for useless peaks, will the field of equals avoid becoming a flat. In other words, equality needs sovereignty in the precise sense he has given it, not command, but the arrival of moments that are ends in themselves. Here the book’s politics show their peculiar reserve. There is no blueprint. Yet nothing in these pages is evasive.

Fascism is described without grand theory as a transcendence tied to a national particularity, strong because it mobilises the thrill of elevation in a closed circle that cannot become universal, doomed because the immanence it offends is larger than any banner and will finally cancel its illusion. The analysis is cold and local, delivered in the middle of waiting for columns of soldiers to arrive and for a city to be entered, delivered in the exasperated nights of explosions and rumours. It follows that the only transcendence still worth the word is one that cancels itself by falling back into immanence, a flare that refuses to crown itself, a summons that refuses to become an office. The courage to act remains, the refusal to become a master remains, and the desire to risk a stake beyond use persists without needing to be decorated as destiny. The closing rhythm brings back everything that mattered and lets it stand without crutches.

The child of play is not a symbol for a fantasy of innocence, it is a practice of beginning that keeps power from hardening into programme. The will to chance is not a slogan for recklessness, it is a discipline of receiving what cannot be commanded. The diary’s test cases remain close, lovers who vanish at the instant of possession, tears that arise when communication breaks, laughter that reenters after fear or shame, a public square where no one is allowed to play master without looking ridiculous. The moral is not that nothing matters, it is that what matters most appears when ends unclench their fist. For this reason Bataille calls even the simplest appearance of immanence a summit, and calls it a ruin of the being that clung to itself, and calls it spiritual without making it serve a church. One can hear in that string of names the patience he learned from failure and weather, a patience that protects the exquisite little surplus by which being is more than it needs to be. Even the apparent aside about Ramakrishna is not ornamental. It is a sketch of a possible tone, a companion of play who treats the world as a comedy of tears and laughter beyond reason and science and words, with the caveat that even the word love can obscure the truth if it is made to shine too brightly. Bataille’s reply is that simplicity decides, that immanence differs little from any ordinary state, and yet that little difference counts more than the most important thing by the standards of utility. This is the secret that ties the diary’s domestic tenderness to its scenes of war time bombardment.

The same "almost nothing" that makes a face suddenly transparent is the almost nothing that makes a crowd suddenly breathing and open, and both are destroyed when an above returns to command. To keep that "almost nothing" alive is the whole work of a life after the gods have left. At the end the wager is restated without flourish. He has finished a plan for a coherent philosophy, he remarks, and the words carry the smile of someone who knows what plans deserve. Night noises continue, rumours hum, children cry, the future is not a solved equation. The only coherence that matters is the coherence of a present that knows how to receive a crest without making it pay, and how to let it go without calling it failure.

To live that coherence is to leave the stage of the masters, to prefer laughter to banners, to choose the lightness of the child over the posture of the conqueror, and to accept that sovereignty is not a possession but a visitation. His book ends, then, exactly where it had to end, with the unspectacular assurance that life can be equal to itself when it gives up pretending to be more, and that what is free does not rule.