Kit Fine’s way into modality begins with a refusal. Most philosophers try to explain essence in modal terms. To say what something is, they ask what it could or could not be. Fine reverses the direction. He argues that what is necessary is necessary because of what things are. Essence is not a shadow cast by modality, modality is a consequence of essence. That reversal matters because it changes what we are doing when we talk about possibility. On the usual picture, you start with a space of possible worlds and then you see what happens to an object across them. On Fine’s picture, you start with the object, or event, or state of affairs, as the thing it is, and you ask what follows from that nature. The necessity you get is the thick metaphysical kind where the world is constrained by what this thing, as this thing, is.

Imagine a simple triangle drawn on paper. You can wonder whether it might have had four sides. If you treat modality as primary, you imagine a “world” where the triangle has four sides and then decide whether that is allowed. Fine’s instinct is to say: stop. Once you have a triangle, being three sided is part of what it is. So the “might have had four sides” claim is blocked because we changed the subject. A four sided figure is a different kind of thing. The modal fact, that this triangle could not have had four sides, is grounded in an essential fact, what it is to be a triangle. This is the basic movement, from essence to modality, from what something is to what is and is not open for it. Fine pushes this movement into areas where philosophers often get tangled, especially with identity across possibilities and with the temptation to treat reference as if it must be tracked via descriptions.

In “Reference, Essence, and Identity” he separates issues that are frequently run together: making sense of de re modality, individuating objects across “worlds”, and whether reference can latch on independently of description. The point, for our purposes, is that Fine wants the thing itself, and its nature, to do the explanatory work.

Hylomorphism is the idea, in its simplest form, that many ordinary things are compounds of matter and form. Matter is the stuff, form is the organising principle that makes the stuff into this unified thing rather than a heap. Fine’s version is a working metaphysical tool: the identity of a material thing is not fixed merely by the bits of matter that make it up, because the form, the way those bits are organised and unified, is part of what it is to be that thing. This matters for trauma and the uncanny because it gives you a precise way to talk about how a scene can feel overdetermined without being fully explained. A hylomorphic object, or a hylomorphic event, can be the same “matter” under a different “form”, and then it is not the same thing. Likewise, the same setting, a room, a street corner, a diner, can carry a different form, a different organising principle, and the modal space around it changes. The uncanny often arrives exactly there: nothing “new” is added, but the form changes, and suddenly different necessities seem to hold. The room is still the room, yet it has become a room where something has to happen, a room where a person cannot remain intact, a room whose silence is not neutral but directive.

Edward Hopper's paintings are depictions of forms that seem to impose modal constraints. Consider Nighthawks. It is often described in terms of isolation, the bright wedge of the diner cut out against a dark city, the sense that the street has emptied out and will not easily refill. A Finean way of putting it is: the painting does not merely show that these people are alone, it presents a structured situation whose essence makes certain possibilities feel closed. It is not just that they are currently not talking, it is that talk, in that glass box of light, feels like something that would have to break a rule. The form of the scene is a kind of containment. The diner is matter, glass, counter, chrome, but the form is the sealed stage, the separation of inside and outside, the insistence that everything social has been reduced to proximity without contact. Once that form is in place, the modal facts follow. In this scene, relief would require an alteration in form, not merely a change in mood.

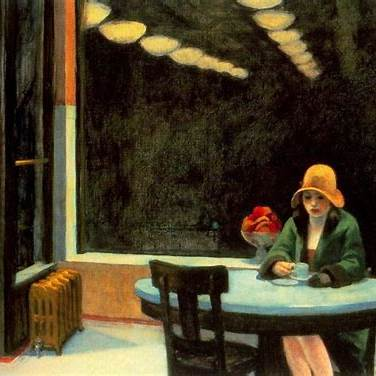

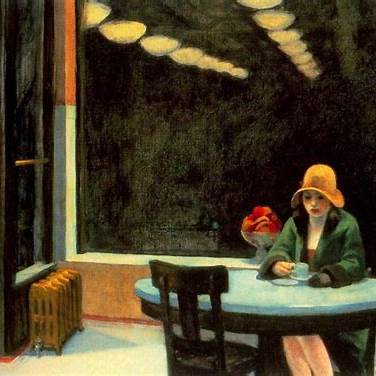

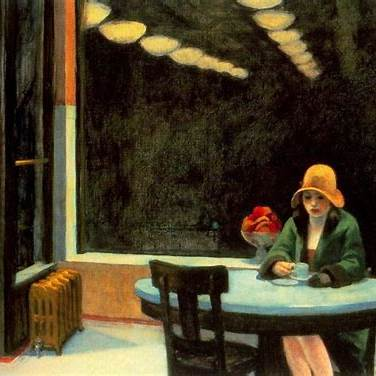

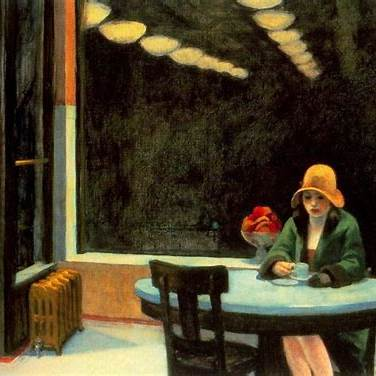

Or take Automat, the woman alone at a table, coffee in front of her, the window behind her reading as a dark blank that refuses to give the world back. On one level it is a simple urban moment. On another level, it is a metaphysical pressure chamber. The blank window functions like a modal barrier. The world that could have been outside is not outside, it has been replaced by an absence. Fine’s approach lets you say the window is not merely a sign of loneliness, it is part of the form that constitutes the situation presented. It helps determine what kind of situation it is, and therefore what kinds of continuation are live. In a “normal” café scene, leaving is easy, meeting someone is easy, the world continues. In Hopper’s constructed form, leaving is thinkable but not the same act. It would be an escape from a sealed episode. The possibility exists, but it is deformed by the essence of the scene.

With Hotel Room, Hopper makes the hylomorphic structure even more explicit. A woman sits on the edge of a bed, head down, holding a piece of paper, caught in sharp, electric shadow. The matter is again straightforward, bed, suitcase, wallpaper, paper. The form is the arrangement that turns these into an ontologically loaded event. This is not “a woman sitting”, it is “a woman paused at the edge of a decision that has already happened in some deeper register”. The paper is a kind of essential anchor, a focus that gathers up the scene’s necessities. If you have ever had a letter, a message, a document that reconfigures your life while leaving the room unchanged, you know what this is. The uncanny comes when the external world does not change enough to match the internal modal shift.

Fine lets us describe this as an ontological shift in what possibilities genuinely remain open, not merely an epistemic shift in what she happens to know. Notice something else about Hopper’s women, especially in paintings like Morning Sun with its hard rectangle of light on the wall and the figure turned toward the day as if the day were an accusation. Hopper’s light behaves less like a formal component, a metaphysical operator. It decides which parts of the room count as real for the scene. It helps constitute the essence of the depicted situation. The light is part of the form that makes this room into this episode. That is why the scenes feel cinematic. Even when nothing is happening, the form has already narrowed the modal field.

David Lynch’s women are often placed inside forms that compress possibility in exactly this way, and the result is frequently uncanny and traumatised rather than merely sad. Lynch's work contains harrowing depictions of sexual violence and the afterlife of abuse, and how women’s suffering is rendered with a mixture of horror and compassion. A Finean approach can describe the distinctive feeling of those scenes without reducing them to either plot mechanics or mere atmosphere. Lynch repeatedly constructs situations whose essence includes a kind of modal trap, where the character can move, speak, even run, but cannot reach certain forms of safety because safety would require a change in the organising principle of the world they are in.

Think of the recurring Lynchian motif of a woman in a room that is just slightly too clean, or a corridor that is just slightly too long, or a domestic interior whose surfaces feel like they are trying to erase a prior event. The uncanny is rarely the arrival of new information. It is the sudden disclosure that the form has changed, or that you have been in the wrong form all along. Fine’s essence first approach makes that disclosure intelligible. It is not that the character learns a secret and now feels afraid. It is that the world has an essential structure such that certain outcomes are now built in, even if the character is still unsure what the outcomes are.

Hopper gives you the pure form of a compressed episode without any overt narrative apparatus. Lynch takes similar forms and then makes them metastasise, he lets them breed, he lets them generate doubles, loops, and ruptures. But the first step is shared: construct a form that narrows what the world will permit.

A way to see the overlap is to focus on windows. Hopper’s women are often framed by windows that either refuse depth, as in the black pane behind the woman in Automat, or deliver depth as something pitiless, as in the bright city or sea that seems indifferent to the interior. Lynch uses windows and thresholds similarly, but with an added metaphysical cruelty: the window suggests that “outside” is not stable. Sometimes the outside is the stage set of normal life, sometimes it is the void behind the set, sometimes it is a different level of the story that has started to leak. Trauma, in this register, is the way the world thereafter constrains what can happen. The traumatic event installs a form. After that, the victim may be in bright daylight, but the modal space is still governed by the installed structure.

Fine’s hylomorphism helps articulate why this feels different from ordinary suspense. In ordinary suspense, the matter is fixed and we await a future fact. In Hopper and Lynch, the form is what grips us. The form makes it feel as if the future is already shaped. You sense necessity without being able to say what is necessary. That is close to the uncanny’s core. The uncanny is often necessity without disclosure, constraint without explicit law.

There is also a Finean point about identity that is useful for thinking about Lynch’s women in particular. If you individuate a person across time purely by a bundle of properties, or by what “world” they are in, you will struggle with Lynch, because he repeatedly makes identity wobble, split, reattach, or become narratively distributed. Fine’s insistence that we distinguish the problem of de re modality from the problem of individuation across worlds helps here. Lynch can be read as dramatising the cost of treating persons as easily reidentifiable across contexts, as if they were just the same “matter” in different scenes.

Instead, his films suggest that persons, especially traumatised persons, are partly constituted by forms, by organising structures that are not merely psychological but world involving. The person after trauma is not simply the earlier person plus a new belief. The form of their practical world has changed, and with it what counts as a live possibility. I have elsewhere talked about “affective modal resonance”, and I claim that it is a feeling that Hopper and Lynch share. The resonance is structural.

Both artists are good at presenting what you might call local necessities, necessities that are not global laws of nature but are enforced by the essence of a situation. In Hopper, the necessity is devastatingly quiet: the silence will not break, the street will not fill, the letter will not cease to mean what it means. In Lynch, the necessity is often violent or hallucinatory: the scene will not stay in one register, the room will not remain a safe container, the past will not stay past. But in both cases, the viewer feels that the world has been made into the kind of world where certain continuations are required, and that requirement is what produces dread.

Once you have the essence of the scene, the modal profile follows. Hopper gives you scenes whose essences are built from geometry, light, and withheld sociality. Lynch gives you scenes whose essences are built from thresholds, performance, doubling, and the persistence of violation. Lynch often returns to the way abuse sits underneath the surface of American normality, and how the films turn that buried fact into a governing structure. Fine gives you a metaphysical grammar for saying what “governing structure” can amount to, not merely as a theme but as a constraint on possibility grounded in form.

This also helps with the feeling that Hopper is “cinematic” and that Lynch is “painterly”. Hopper shows how to make a world in which the smallest adjustment, a tilt of the head, a rectangle of light, a cup held too tightly, can carry the weight of a necessity. Lynch shows what happens when that same technique is applied to a world where trauma has already altered the forms of intimacy, privacy, and identity. The uncanny is what realism looks like when the form that trauma installs becomes visible.

Why do Hopper’s women and Lynch’s women so often seem not merely sad or endangered, but caught inside situations that feel metaphysically hostile, as if the world itself has taken on a form that collaborates with harm? A Finean answer says that both artists are unusually adept at presenting forms that determine modal profiles, and that trauma is experienced, and represented, as a deformation of form rather than simply as an episode that happened in time.

To see this, it helps to think again about Fine’s insistence that essence is prior to modality. If the essence of a situation includes certain structural features, then what can and cannot happen within it is no longer an open question. The situation itself answers it. Hopper repeatedly paints women in situations whose essence is defined by enclosure, exposure, and suspension. The enclosure is often architectural, a room, a hotel, an apartment, but it is never merely physical. It is formal. The room is not just a room, it is a room whose organising principle is waiting without expectation of fulfilment. The exposure is often visual, windows, light, visibility, but again it is not simply optical. It is ontological exposure, being present in a world that sees without responding. Suspension is the temporal form that results. These women are not clearly before or after an event. They are held in a present that feels thick, resistant, almost adhesive.

Fine’s metaphysics says a temporally suspended situation is not just one in which we lack information about what happened or will happen. It is one in which the essence of the situation does not yet permit certain transitions. In a normal narrative world, time is a medium of resolution. In Hopper’s worlds, time is often part of the constraint. The woman in Hotel Room inhabits a form in which pausing is structurally favoured over action. That is why viewers so often feel that something has already gone wrong, even though nothing visible has occurred. The wrongness is not an event, it is a modal configuration.

When Lynch places women in analogous configurations, the effect is intensified by narrative and sound, but the underlying metaphysical move is similar. Lynch is often described as exploring dream logic or irrationality, but this can be misleading. The logic is often extremely tight, but it is a logic of essence rather than a logic of inference. Once the form of the situation is set, its consequences unfold with a kind of grim necessity. This is why scenes of abuse or threat in Lynch feel less like interruptions of normal life and more like disclosures of what normal life, in that world, already was.

This is especially evident in Lynch’s repeated use of performance and doubling with female characters. A woman appears as herself, as another version of herself, as a performer playing a role, or as an image watched by others. The temptation is to read this epistemically, as confusion about identity, or narratively, as a puzzle to be solved. A Finean reading instead treats these doublings as signs that the essence of personhood in that world has been destabilised. The form that ordinarily unifies bodily continuity, psychological continuity, and social recognition has fractured. Once that form fractures, new modal facts appear. Certain protections no longer hold. Certain harms become admissible in ways they previously were not.

Trauma, in this metaphysical register, is not a memory of violence or violation but the installation of a new form that governs what counts as possible from then on. After trauma, the world may look the same in terms of matter, the same rooms, the same streets, the same bodies, but the form has changed. Fine’s hylomorphism gives us a way to describe this. The matter remains, the form alters, and therefore the thing is no longer the same kind of thing. A life after trauma is not merely the same life plus an awful fact. It is a life whose modal space has been reconfigured.

Hopper captures this reconfiguration at the level of stillness. His women often appear as if they are already living in a world that has narrowed around them. The narrowing is visible in posture, in the way bodies turn inward or align with architectural lines, in the way light presses rather than reveals. Lynch captures it at the level of rupture and repetition. His women often move through scenes that replay, distort, or refuse closure. But in both cases, what the viewer encounters is not simply fear of what might happen, but dread grounded in what the situation already is.

This also explains why the uncanny is such a persistent effect in both bodies of work. The uncanny, classically, arises when something is both familiar and alien. In Finean terms, it's a mismatch between matter and form. The matter is familiar, a living room, a bed, a face, but the form organising it is not the one we expect. The world looks like a normal world, but it behaves like a different kind of world. That is exactly the condition under which modal judgements become unstable. We find ourselves unsure not just of what will happen, but of what can happen at all.

In Hopper, this instability is quiet and corrosive. A woman sits in sunlight, and yet the sunlight does not console. A window opens onto a city, and yet the city does not invite. These are not failures of perception. They are clues about essence. The scene is not of the comforting kind. Its form does not include consolation as a live option. In Lynch, the same instability becomes explicit and often brutal. The woman may smile, sing, or perform happiness, but the performance sits inside a form that permits violation, erasure, or substitution. The smile does not protect her because protection is not among the admissible outcomes in that configuration.

If we push Fine’s framework a little further, we can also understand why these representations resist moralising. It is tempting to ask whether Hopper’s women are victims, or whether Lynch’s women are exploited by the narrative. Those questions miss something structurally important. Both artists are less interested in individual moral failure than in the way worlds are built so that harm is easy, or even necessary. Fine’s emphasis on essence shifts attention from isolated actions to the natures of situations. A situation whose essence makes certain harms admissible is already ethically compromised, regardless of whether any single agent intends that harm.

Both are artists of modal violence. They show worlds in which the violence is not always enacted on screen or canvas, but is encoded in the very shape of possibility. For women in particular, these worlds are often shaped by visibility without recognition, by intimacy without safety, by domesticity without shelter. Trauma is not an intrusion into these worlds. It is what these worlds are good at producing, as if the world is a machine producing trauma.

Seen this way, Fine’s metaphysics allows us to say that what feels uncanny or traumatising in these images is not merely a matter of subjective response. It is a response to an objective feature of the represented world, namely a form that constrains possibility in disturbing ways. Hopper paints that constraint at rest. Lynch sets it in motion. In both cases, the viewer is invited not just to witness suffering, but to inhabit, however briefly, a world whose essence makes that suffering feel structurally inevitable.

I want to formalise this argument a bit more explicitly while remaining faithful to the aesthetic phenomena and so what follows is not a change of topic but a tightening of articulation. The aim is to make clear, in explicitly metaphysical terms, how Hopper’s paintings of women and Lynch’s women centred scenes can be understood as presenting structured modal claims grounded in form, how those claims are best captured by a Finean essentialist framework, and how trauma and uncanniness emerge as consequences of altered modal structure rather than as merely psychological or narrative effects.

So I'll go back to the core Finean thesis. (I know, I know, but this is so that I stay clear about what I take Fine to be about.) I'm saying that for Kit Fine, modality is grounded. Necessity and possibility are not primitive features of a space of worlds but are derivative from facts about essence. For any entity x, what is metaphysically necessary for x is fixed by what x is. Modal facts therefore supervene on essential facts. This can be expressed schematically: for any proposition p about x, p is necessary if and only if p follows from the essence of x. Conversely, p is possible for x if and only if p is compatible with the essence of x.

Fine’s position requires rejecting two assumptions that are often tacit in aesthetic interpretation. First, that modal space is globally uniform, that is, that what is possible is fixed independently of the internal structure of particular situations. Second, that modal judgments in art are merely projections of viewer psychology rather than responses to objective features of the represented world.

So what does he put in their place? Well, his framework allows for local modality. Different situations can carry different modal profiles because they instantiate different essences. To extend this to scenes, we treat a depicted situation not as a mere aggregate of objects but as a structured entity in its own right. This move is licensed by Fine’s hylomorphism.

A hylomorphic entity consists of matter organised by form. The form is not reducible to the matter. It is the principle that unifies the matter into a determinate kind of thing. Applied to scenes, the matter consists of physical elements, bodies, furniture, architecture, light, spatial relations. The form consists of the organising structure that makes these elements into a particular kind of situation rather than another.

Let S be a depicted situation in a Hopper painting. S is not identical to the set of objects it contains. S is a hylomorphic entity whose form determines its identity and modal profile. Formally, we can say: S exists as a situation of kind K if and only if its matter M is organised according to form F_K.

The modal facts about S, what can happen within S without destroying its identity as S, are determined by F_K.This allows us to distinguish two kinds of change. A material variation alters M while preserving F_K. A formal variation alters F_K and thereby produces a different situation type.

Hopper’s paintings systematically minimise material variation while making form maximally salient. This is why so many interpretations stall when they ask what will happen next. The paintings are not underdetermined narratives. They are determinate modal structures.

Consider a Hopper painting of a woman alone in a room with a window. Let us call this situation S₁. The matter includes a woman, a chair or bed, a window, light, and an exterior view. The form F₁ includes enclosure without protection, visibility without reciprocity, and temporal suspension. These features are not psychological states attributed to the woman. They are structural features of the situation as presented. They determine which transitions count as continuations of S₁ and which would transform it into a different situation altogether.

For example, suppose we imagine the woman receiving comfort from another person who enters the room and alleviates her distress. That event is logically possible. It is physically imaginable. But relative to F₁ it is modally excluded. Its occurrence would destroy the form that constitutes S₁. It would not be a continuation of S₁ but a replacement of it by a different situation S₂ with a different form F₂.

Thus the sense that relief cannot simply arrive is not an affective illusion. It is a response to the essence of the situation. This is the crucial move. Hopper’s paintings do not say that certain things will not happen. They say that certain things cannot happen without the world ceasing to be the world it is. This is a metaphysical claim about essence, not a prediction about events.

Trauma enters the picture when we notice that many Hopper situations instantiate forms that closely resemble the forms imposed by traumatic experience. Trauma, in this formalised sense, is not defined by a past event E alone. It is defined by a transformation of form. Let a subject’s pre trauma world be organised by form F_normal, under which trust, continuity, and agency are live possibilities. After trauma, the same material world persists, but it is reorganised under form F_trauma.

Under F_trauma, certain possibilities that were previously admissible are now excluded, and certain threats are now structurally salient. Hopper’s women often appear already situated within F_trauma type forms. The paintings do not depict the traumatic event. They depict the world after form has changed. This explains the pervasive sense of aftermath without narrative. The paintings present worlds whose modal structure bears the mark of trauma even in the absence of explicit violence.

Across works such as Automat, Hotel Room, Morning Sun, and many others, we find repeated instantiations of forms with the following essential features. First, spatial containment that is not protective. Second, exposure to light or visibility that does not generate recognition or care. Third, temporal stasis in which action does not accumulate toward resolution. These features jointly define a kind of situation K_H.

From these essential features, modal consequences follow. In any situation of kind K_H, certain transitions are blocked. Spontaneous rescue is not available. Social recognition is not forthcoming. Time passing does not guarantee change. These are not empirical generalisations but essential constraints. They hold in virtue of what K_H is.

The uncanny arises because the matter of K_H is drawn from everyday life. Rooms, cafés, sunlight, ordinary clothing. Viewers initially assume F_normal. They expect the modal profile associated with ordinary domestic or urban situations. But the painting presents F_H instead. The resulting mismatch between expected and actual modal structure produces uncanniness. The world looks familiar but behaves differently.

This same formal analysis extends directly to David Lynch. Lynch’s cinema repeatedly constructs situations whose forms impose hostile modal profiles, especially for women. Like Hopper, Lynch often withholds explicit explanation. But Lynch adds dynamism, repetition, and ontological instability. His worlds do not merely constrain possibility. They actively deform identity.

To formalise this, consider a Lynchian situation S_L involving a woman in a domestic or performative space. The matter may include a house, a stage, a nightclub, a bedroom. The form F_L includes instability of identity, permeability of boundaries between private and public, and the persistence of violation across time and representation.

Under F_L, the unity conditions for persons are weakened. The usual hylomorphic unity of body, psyche, and social role does not hold reliably.

Modal consequences follow. Under F_L, it is possible for a person to be split into doubles, to be replaced, to be watched without knowing, to be harmed without the harm being localised in time. These are grounded in the essence of the situation type. The world itself permits them. This is why trauma in Lynch is not merely represented but enacted at the level of ontology. The traumatised woman does not simply remember violence. She inhabits a world whose form makes recurrence, repetition, and erasure admissible.

Hopper shows us such worlds frozen at the point of containment. Lynch shows us such worlds unfolding, mutating, and feeding back on themselves. The formal parallel can now be stated precisely. Hopper and Lynch both construct hylomorphic situations whose forms impose restrictive or hostile modal profiles. In Hopper, these profiles are static and quiet. In Lynch, they are dynamic and violent. In both cases, women are placed within these forms in ways that make trauma structurally intelligible. The affective resonance between the two artists arises because they are working with homologous metaphysical materials.

This formalisation clarifies the ethical stakes. If modality is grounded in essence, then representing a world is representing a set of necessities. Hopper and Lynch are showing worlds in which suffering is a consequence of form. The discomfort their work produces is metaphysical. We are forced to confront the possibility that worlds like these exist, not as exceptions, but as structured realities.

Seen this way, the uncanny is the phenomenological signature of encountering a world whose form we did not anticipate. Trauma is the mechanism by which such a form comes to govern possibility. Fine’s metaphysics allows us to say this without metaphor, without reduction, and without sentimentality. It lets us treat Hopper’s women and Lynch’s women as inhabitants of worlds whose modal structures are the true subject of representation.