Imagine Gaza Like This

Imagine a densely populated strip of land with over 2 million lives crammed into a mere 140 square miles. This would be a place comparable to America's largest cities . Imagine that in this place 40% of its population is aged 14 or younger, presenting one of the globe's 20 youngest populations. Imagine its median age is 18 . Imagine that in this place the average life expectancy is 75.7 years.

Imagine a hostile neighbour, with support of others, blockades the place. Imagine that the International Monetary Fund analyses the situation and concludes that 60% of the people in this place live in poverty. Imagine unemployment rates of 44% Imagine that the GDP per capita hasn't exceeded $6,500 for nearly thirty years. The neighbour blockading it has a GDP eight times higher.

Imagine high infant and maternal mortality rates . Imagine high drop-out rates and large class sizes for primary school-aged children. This would be an urban dystopia. It would be a place where everyone was poor. It would make sense to look at such a place through the lens of poverty as well as other factors such as post colonialism, race, ethnicity and religion etc.

This place is of course Gaza.

Poverty is often accompanied by negative attitudes and stereotypes that perpetuate social stigmas. Negative attitudes towards poverty often stem from psychological biases and cognitive heuristics that simplify complex social issues. The "just-world hypothesis," for instance, leads people to believe that individuals are in control of their destinies and, therefore, responsible for their own poverty. This cognitive distortion creates a blaming mentality that undermines systemic issues contributing to poverty.

Cultural narratives and media portrayals play a significant role in shaping public perceptions. Media tends to highlight extreme cases or perpetuate stereotypes of impoverished individuals, reinforcing the notion that poverty is solely a result of personal failure. This oversimplified narrative overlooks systemic factors such as unequal access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities.

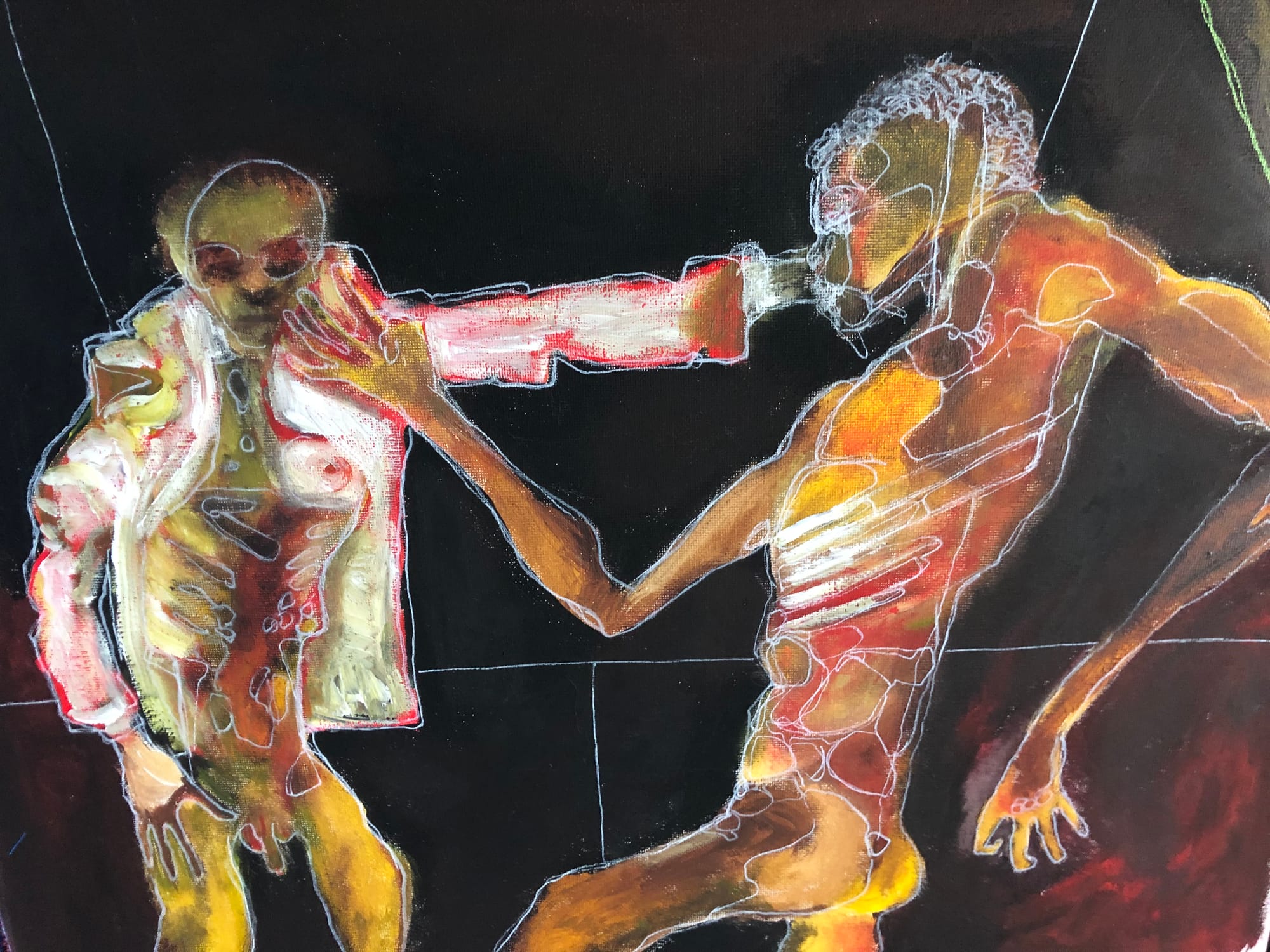

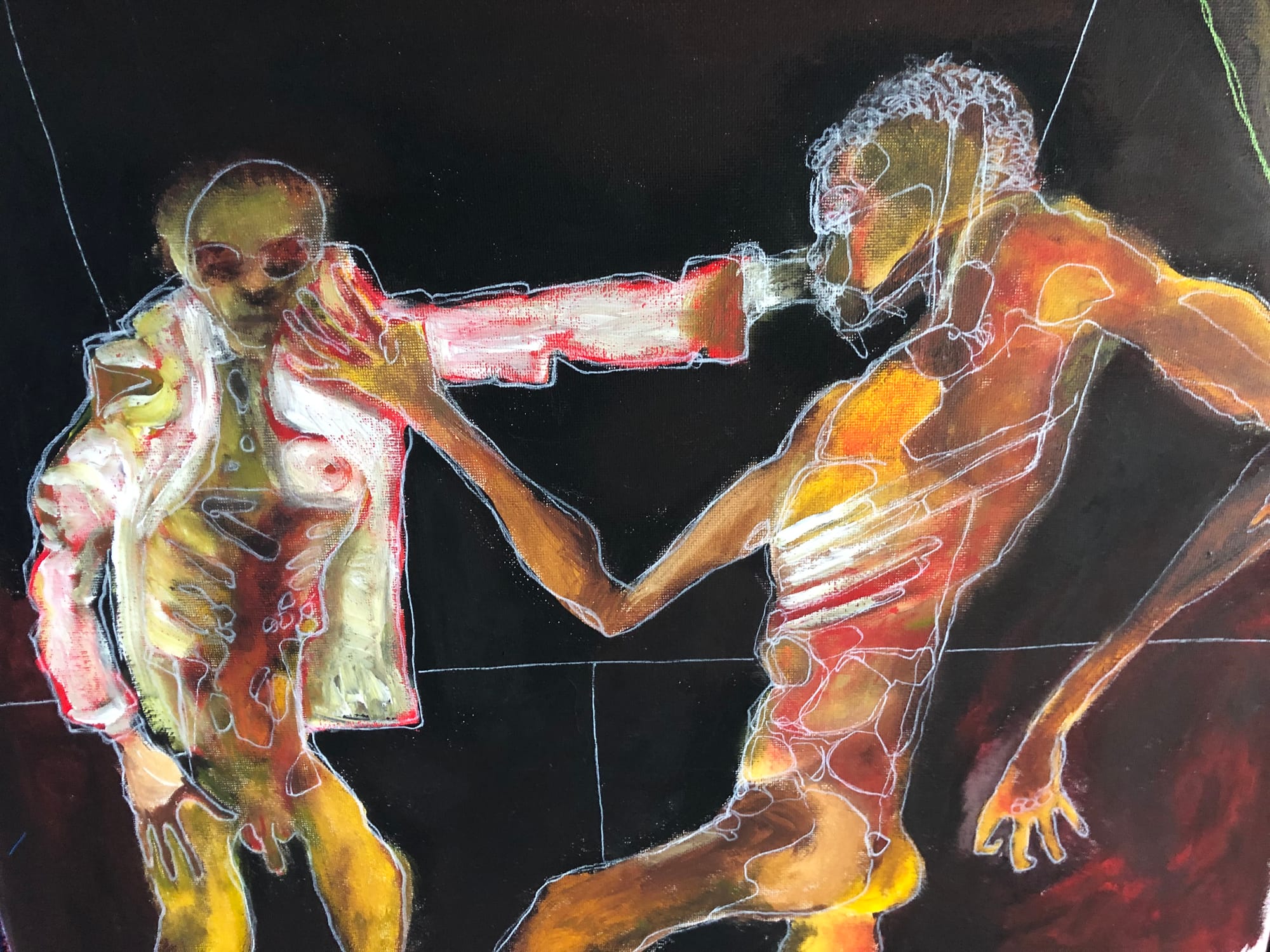

Societal attitudes towards poverty are often steeped in historical stereotypes that portray the poor as lazy, unmotivated, or even criminal. These stereotypes contribute to the dehumanization of impoverished individuals, fostering a sense of "otherness" that further isolates them from mainstream society.

Negative attitudes towards poverty can influence public policy, leading to the implementation of punitive measures rather than holistic solutions. Welfare programs may face scrutiny and budget cuts, perpetuating a cycle of poverty rather than addressing its root causes.

Poverty is not only a socioeconomic challenge but can also give rise to complex interpersonal dynamics, including conflicts within the impoverished community itself.

The psychological concept of scarcity suggests that individuals experiencing poverty may develop a scarcity mindset, wherein competition for limited resources intensifies. This scarcity mentality can lead to internal strife as individuals within the impoverished community vie for the same opportunities, creating a sense of rivalry.

The societal stigma attached to poverty may lead individuals to internalize negative perceptions. Internalized stigma can manifest as feelings of shame or inferiority, fostering a desire to distance oneself from others experiencing similar economic challenges. This internalized stigma contributes to divisions within the impoverished community.

In economically distressed communities, resources such as job opportunities, affordable housing, and social services are often scarce. The intense competition for these resources can create a survival-of-the-fittest mentality, where individuals may view their peers as competitors rather than allies, leading to internal conflicts.

Historical socio-economic policies have sometimes intentionally created divisions among the poor to maintain control. Policies that disproportionately impact specific demographics within the impoverished community may contribute to internal conflicts, perpetuating a cycle of division.

Basically, if the poor are stereotyped as a despised group then identifying a group as poor is a reason for dealing with them with disdain. It's helps explain the mass killing of children, and unarmed civilians. The stereotype turns the poor into virmin and so can be exterminated.

In this way all of us need to see that what is happening in Gaza is a war on poor people by rich people. The conflict in Gaza is a complex web of historical, ethnic, religious, and post-colonial dynamics, with this additional dimension often overlooked — poverty. And this feature is one that actually the one that makes a huge difference - because Jews, Muslims Christians, Atheists, Nationalists don't permit butchery. Nor do people rightfully agrieved by a post colonial settlement. But few people have a problem with exterminating virmin. An additional benefit of looking at the conflict through the lens of poverty is that you can't so easily dismiss it as being a conflict in which you have no stakes because you're not Jewish nor Muslim, say. Everyone is part of the class war! And for most of us, poverty is a real threat.

So I'm saying that we should focus on the socio-economic divide exacerbating existing tensions in this place at least as much as the religious, ethnic, post-colonial nationalist elements.

Gaza, predominantly populated by Palestinians, finds itself pitted against Israel, a nation characterized by its relative affluence. The attitudes toward the poor in Gaza are entangled with multifaceted layers of repulsion, ascribing subhuman qualities to an entire population. These negative perceptions are often steeped in crude ethnic and religious stereotypes, perpetuating an 'us versus them' mentality.

Despite the ethnic and religious narratives that dominate discussions, the Gaza conflict fundamentally boils down to a class war. The assumption that being Arab or black equates to poverty perpetuates a cycle of discrimination. Instances of mistaken identity, such as the wrongful arrest of affluent Palestinians or black individuals, underscore the deep-seated association between race and economic status.

Drawing parallels with the IRA conflict in Ireland offers insights into how the British government's perception of Irish Republicanism as a working-class movement shaped their response. The categorization of both sides as impoverished allowed the conflict to persist, with wealthy UK citizens disregarding Belfast as just another struggling industrial city.

In contrast to the treatment of Gaza, wealthy nations like the USA, GB, China, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan are part of the global elite, integrating seamlessly into international governance structures.

Their affluence shields them from the negative stereotypes associated with poverty, fostering acceptance within the global community. (Of course internally, these rich nations treat their own poor horribly.)

The international community's willingness to engage with affluent leaders in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan stands in stark contrast to the disdainful treatment of Palestinians. This disparity reflects a global tendency to overlook the wealthy elite's roles in perpetuating conflicts while directing attention toward impoverished populations.

The Gaza conflict is not solely an ethnic, religious, or post-colonial struggle; it is fundamentally a clash between socio-economic classes. The intertwining of poverty with ethnicity and post-colonialism has led to the dehumanization of the people of Gaza.

Acknowledging the role of class struggle in this conflict is crucial for understanding its dynamics and working towards a more inclusive and just resolution.