Nietzsche and Virtue

interview by Richard Marshall

'Solitude might be Nietzsche's most innovative conception in virtue theory. When I started the book, I didn't plan to write about it at all, but some of my colleagues suggested taking a look. This is where the distant-reading method paid off. I realized that, for him, solitude is a disposition that manifests in particular in the context of intra-group and inter-group relations. The person who embodies solitude is disposed to look for, point out, and ridicule the most contemptible aspects of their ingroup, especially if it's an unelective rather than elective affinity (e.g., family, nationality). Nietzsche does this all the time, for instance when he rags on the Germans while praising other nationalities and ethnicities. In a sense, it's the collective version of what he celebrates in the pathos of distance and having a sense of humor. With those two, one is able to laugh at and ridicule (aspects of) the I . With solitude, one is able to laugh at and ridicule aspects of the we .'

'I think Nietzsche is very insightful when it comes to the social scaffolding of virtues. He seems to think that drives become virtues, as I described above, in many cases through self-fulfilling prophecies. People attribute a trait to someone, and if they have a drive that could with a little modification answer to that attribution, they accept it and change to make the attribution retrospectively accurate. There's some evidence in social psychology that this phenomenon is real.'

'To be frank, I don't have a lot of patience for anti-naturalism. As many virtue ethicists and epistemologists (most of them not Nietzscheans) like to point out, we use attributions of virtues and vices to predict and explain behavior. In a recent study on which I'm a co-author, we surveyed about 45,000 people in dozens of countries and found that their level of open-mindedness was either the best or one of the best predictors of whether they rejected COVID conspiracy misinformation and accepted expert consensus on the advisability of lockdowns, masking, social distancing, and other measures.'

Mark Alfano studies how people become and remain virtuous, how values become integrated into people's lives, and how these virtues and values are (or fail to be) manifested in their perception, thoughts, feelings, deliberations, and actions. One of the guiding themes of his work is that normative philosophy without psychological content is empty, but scientific investigation without philosophical insight is blind. Here he discusses Nietzschean scholarship, distant reading, Nietzschean instincts, drives and the enchanting abundance of types, the Nietzshean modern type, curiosity, the pathos of distance, sense of humour, solitude, three types of conscience, hunches about future studies, virtue and naturalism, moral technologies, why anti-naturalism and epiphenomenalism are mistakes, and demandingness.

3:16: What made you become a philospher?

Mark Alfano: It was Nietzsche, actually! I was a pimply high-schooler in New Jersey, raised by right-wing Evangelicals (think Trump, QAnon, and so on...), when I first started reading him. I have to say, that's probably not a great route into philosophy, as Nietzsche tends to inspire fandom -- especially in people who've been damaged by the more virulent forms of Christianity. Teenage boys should probably be banned from reading Nietzsche. I certainly was a fan for years. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Nietzsche under the supervision of Alexander Nehamas at Princeton. It wasn't good. When I enrolled in grad school at CUNY, I decided to take a hiatus. But near the end of my PhD, one of my advisors suggested that I give it another go and submit a paper to a special issue of the Journal of Nietzsche Studies . To my surprise, it was accepted (it's the background for my account of Nietzschean drives in the book, in fact). That led me to think that maybe I should revisit him -- no longer as a fan but more as an interpreter and critic.

3:16: Your reading of Nietzsche’s moral psychology begins with you castigating many previous readers of Nietzsche for being careless and slap-dash in their approach – Heidegger the obvious worst culprit in that he ignored what Nietzsche actually wrote, but there are many others you accuse of being distorting and close to just making it up. You propose a solution to this problem, with a view to avoiding the replicability crisis that we’ve seen in other disciplines. Distant reading is the strategy you recommend and use yourself to compliment close reading of relevant text. So can you sketch for us what ‘distant reading’ is and why it’s a benefit, and also why you think so much of Nietzschean scholarship has been so poor and yet full of dogmatic interpretations?

3:16: Did I come across as too acerbic? There's plenty of good work being done on Nietzsche in Anglophone philosophy (and of course, also in German philosophy and elsewhere), especially by younger scholars like Paul Katsafanas, Rachel Cristy, Rebecca Bamford, Joel van Fossen, and Anthony Jensen -- though also by more seasoned hands such as Bernard Reginster, Gudrun von Tevenar, Keith Ansell-Pearson, and Ken Gemes. It seems to me, though, that there are several reasons why much, perhaps most, Nietzsche scholarship is poor. First, he's still sort a of a niche or fringe figure. If you go to /philjobs and look for positions listed over the years with an AOS (area of specialization) in Kant or Plato or Aristotle, you'll see several job openings. I don't think Nietzsche has ever featured in the same way. That means the number of people engaging with the secondary literature on Nietzsche is relatively small, and that many of those involved do it as a side-project rather than their main thing (that includes me -- most of my work is in contemporary epistemology and moral psychology).

Second, Nietzsche was only rehabilitated as a respectable philosopher in the last half-century or so by Walter Kaufmann, Arthur Danto, and a few others. They spent a lot of time just trying to convince people that Nietzsche was a philosopher and not a Nazi (unlike Heidegger...). In the meantime, his reputation had been ruined in the English-speaking world by people like Bertrand Russell, who seems to have understood precisely nothing of what Nietzsche actually said and potentially only ever read a few paragraphs of poor translations of his writing. So there isn't as much of a tradition to draw upon when interpreting him. Third, until very recently, Anglophone philosophers didn't even have access to scholarly translations of all of Nietzsche's writings. Why is Daybreak (or, if you prefer, Dawn or Aurora ) so little-discussed in Anglophone Nietzsche scholarship? Almost certainly because Kaufmann never issued a translation. It's only recently that Cambridge University Press has put out authoritative translations of various works, including important ones like Daybreak.

Fourth, and this is maybe a bit tendentious, I suspect that a lot of the attention in Nietzsche scholarship has been organized around his use of italics. Why is there so much attention paid to resentment ( ressentiment , if you insist on using the French transliteration as Kaufmann did -- incidentally Kaufmann italicizes every use of ressentiment in the Genealogy , even though Nietzsche didn't)? Why are there so many papers on the sovereign individual? Because Nietzsche put them in italics, and that bewitched a couple generations' worth of scholarship. It's a bit embarrassing, but I can't think of a more plausible explanation. Still another issue is that Nietzsche is idiosyncratic in both his interests and the positions that he takes on various issues. Interpreters often want to pigeonhole philosophers into contemporary categories, and that can be pedagogically valuable.

But it tends to at least warp or distort the philosopher being interpreted, and when that philosopher is as idiosyncratic as Nietzsche is, it can be downright Procrustean. Arguably, Brian Leiter's recent collection of essays does something along these lines: his Nietzsche is sort of a palimpsest of Quine and Jonathan Haidt. Finally, Nietzsche himself is likely to blame. His writing is notoriously tricky and elusive. It's not always clear whether he's saying what he thinks or what someone else might think (or what he used to think -- he seems to have changed his mind about various issues across his philosophical career). It's not always clear when he's being ironic or sarcastic. As I point out in my book, he jokes around a lot. And of course some of his writing explicitly puts words into the mouths of characters that he's created, such as Zarathustra. It would be naive to think Zarathustra = Nietzsche. But it would also be silly to think that Nietzsche doesn't believe anything he has Zarathustra say. (Of course, similar issues arise with Plato and the character of Socrates in his dialogues....) So, all in all, I'd say the problem is that a small number of part-timers without a lot of tradition and resources to draw on did an understandably mediocre job of curating and interpreting an extremely challenging corpus.

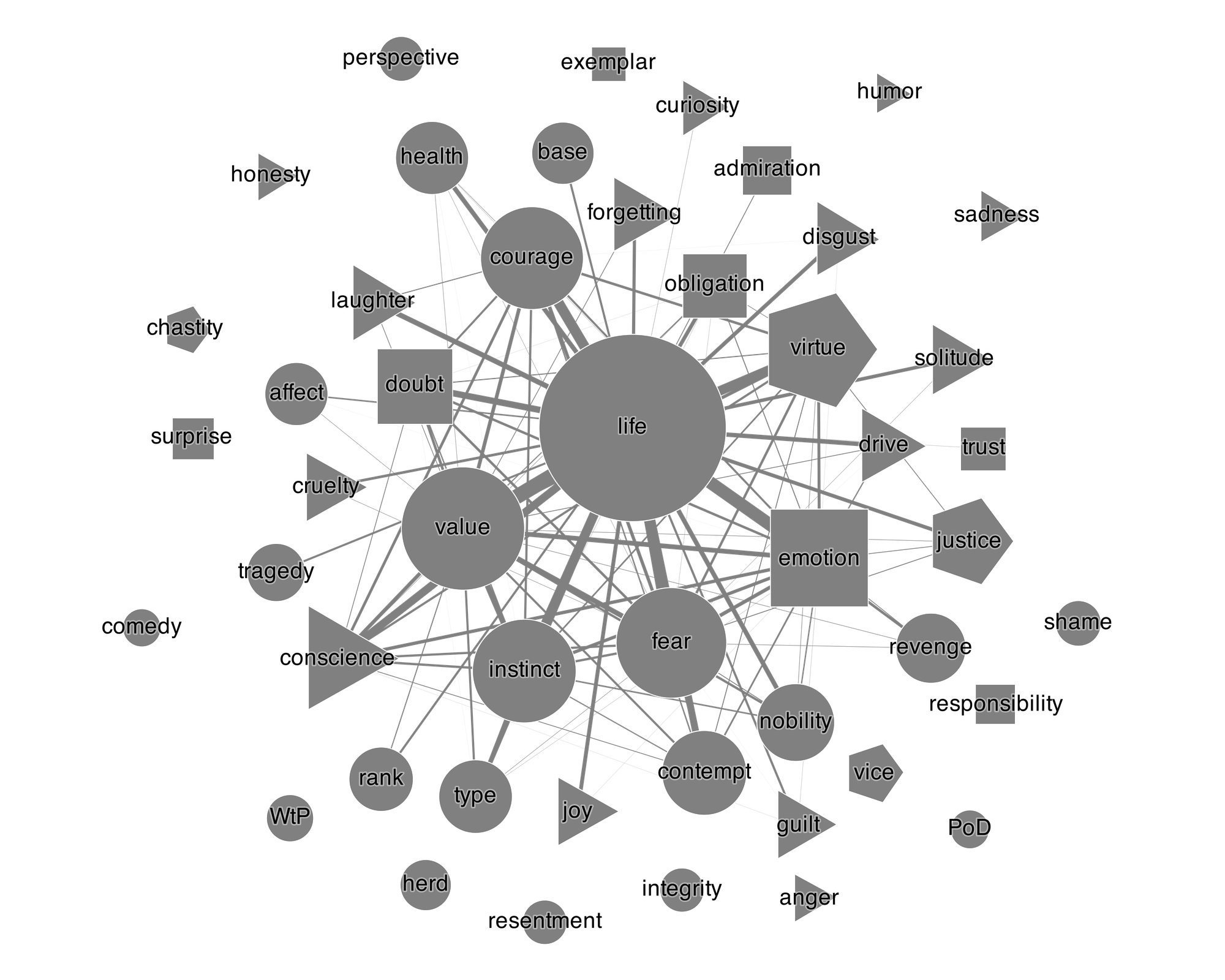

To help cope with these problems, I employ distant reading in the book. The basic idea is extremely flat-footed and simple-minded: I come up with a list of concepts or constructs that, based on my reading of Nietzsche over the years as well as my familiarity with the secondary literature, are probably important for him. Then I associate each concept or construct with the German words (actually word stems) that he uses to refer to or express it. For instance, the concept of virtue is associated with anything beginning with 'tugend'. Some concepts are associated with only one word stem, others with multiple. This is made a bit difficult because Nietzsche updated his spelling in the mid-1880s. For instance, in his earlier work, he uses 'instinct' and 'affect', but later he uses 'instinkt' and 'affekt'. In order to get all and only the word stems you want, you need to be aware of the text at a detailed level. Once I'm satisfied with the list of word stem(s) associated with a given concept, I then run an algorithm over the entire corpus to find out which passages contain which concepts. I initially did this all by hand via www.nietzschesource.org , which is an outstanding resource. It took months. But then I met a computer scientist by the name of Marc Cheong who figured out how to do it automatically in the course of about a minute. We eventually published a tool that anyone with minimal coding skills can use to replicate and extend what I did in the book.

The next step is really the one you asked about: how to use distant reading to complement close reading? There are two main uses. First, this kind of analysis makes it possible to answer questions of the form, "What does Nietzsche talk about when he talks about X?" So for instance, what else does he talk about when he talks about virtue, or about courage, or about contempt, or about conscience? In the book, I visualize these interrelationships with (what I think are) pretty pictures using Gephi.

But the actual analysis is entirely structural and mathematical. Answering that question on its own doesn't tell you how Nietzsche relates various concepts, but it strongly suggests that he does relate them. This leads to the second thing, which is guided close-reading. The idea is that if Nietzsche keeps talking about X and Y in the same passage, he probably thinks they're related in some way. So then I go through all of those passages with an eye specifically to the relationship between those concepts. This was a new way of reading for me. Previously, I'd either read cover-to-cover or would have a hunch and search for one or two relevant passages. Forcing myself to engage with all and only the passages in which concepts of interest crop up led me to formulate some new ideas, especially when it came to Nietzsche's thoughts about perspectivism, about having a sense of humor, and especially about what he calls 'solitude'.

I want to be clear that I don't think the computers will ever replace the people when it comes to interpreting philosophical texts. It's rather that we humans can use computers to help keep ourselves honest and unearth patterns that would be difficult to detect if we did everything manually. But we are the ones to offer the interpretations, and our interpretations will always need close, careful, and contextualized reading. That (along with the pretty pictures) is what I think distant reading is or at least should be about.

3:16: Instinct, drive and type are three contentious terms that are important in the Nietzschean literature. So how do you understand these things as he developed his thinking about them over time? One thing I think you think very important is to see drives as helping us to understand non-consequentialist judgment, the seemingly irrational behaviours of a person, types as constellations of such drives, so is the best way to understand Nietzsche is as a type-relative unity of virtue theorist?

MA: I argue that Nietzsche understands drives as act-directed motivational and evaluative dispositions. An agent's drives move her to engage in and positively evaluate a range of characteristic actions (e.g., the sex drive towards erotic activity, or the aggressive drive towards harming someone or something). Importantly, this motivation persists even when the agent can easily foresee that performing the action in this particular instance will lead to consequences that she strongly disprefers. In other words, I can be driven to do this sort of thing (e.g., act aggressively) even when I know full well that it's going to get me in a lot of trouble. If this is right, then drives are directed at action-types rather than teleologically-specified states of affairs. This is why we sometimes get restless and feel the need to do something even if the world is more or less as we prefer it. And it can help to explain what might otherwise appear to be blatant irrationality (such as acting aggressively or even violently even though they know it's likely to land you in prison). Nietzsche actually talks in quite a few passages of the "criminal type," which he associates with this unfortunate compulsion to aggress in conditions where there is no socially sanctioned object against which it's permissible to aggress (e.g., a state of peace rather than war).

Nietzsche seems to think that some drives are innate, and those are the ones he tends to call instincts. He also seems to think that all drives are mutable to a certain extent, but only within boundaries. So it's possible to sublimate, for instance, the erotic drive and transmute it into something like romantic love. But it's probably not possible to turn it into a passion for counting paperclips (though who knows? -- people can be polymorphously perverse). Instincts, in particular, seem for Nietzsche to be less susceptible to this sort of transformation. And, I should note, the distant-reading methods I use in the book suggest that over the course of his career he became increasingly concerned with instincts and less concerned with acquired drives.

The way Nietzsche uses 'type' seems to refer to a constellation of drives embodied in an individual. So if you and I have all or mostly the same drives, then we belong to the same type. A lot of the secondary literature latches onto Nietzsche's distinction between higher and lower types, but he clearly doesn't think that there are just two. At one point he refers to the "enchanting abundance" of types, and he seems to find the fact of human diversity itself an object of wonder. Finally, for Nietzsche, a drive is or counts as a virtue for a given individual if they're able to express it in ways that don't undermine the expression of their other drives, don't lead them to condemn fixed aspects of their selves, and don't lead to severe social sanction, especially sanction that gets internalized as self-loathing. That's a lot, but if it's on the right track, it means that Nietzsche accepts a modest unity-of-virtue thesis, where the unity is relativized or indexed to the agent's type.

3:16: You examine Nietzsche’s own modern virtue type. Why isn’t it possible to give a universal account of virtues within the Nietzschean socio-moral framework ? Is this why Nietzsche thinks the next best thing to having a perspective-free view is to try and take up different perspectives over time - and why does this in turn lead to his requirement that we get a grip on our emotions?

MA: The main reason I focus on Nietzsche's own type is that he has the most to say about it. In the book, I also devote some pages to the type of the criminal and various other types, but their details are left indeterminate in his corpus just because he has much less to say about them. The reason you can't give a universal account of virtues in the Nietzschean framework is precisely the "enchanting abundance of types" I mentioned earlier. If there were only one type -- one constellation of drives for all people -- it would be feasible. But, on the assumption that Nietzsche is right about the diversity of types, it's just not in the cards. This is actually a really important point for Nietzsche. It forms the basis of his critiques of slave morality and of democracy. The slave moralist insists that everyone act in ways that would only be expressive of the slavish type. Democracy (at least as he understands it) demands that everyone act as if there is no diversity of types, with some higher and others lower.

The issue of perspectivism is, I think, actually quite distinct from all this. When Nietzsche talks about perspectivism and about gaining control of "one's Pro and Con" (one's positive and negative emotions), he's actually recommending an epistemic methodology. He thinks that inquiry is directed by emotions, and that different emotions make us differentially sensitive to different properties -- especially evaluative properties. So for instance, think of fear. When you're afraid, that disposes you to look for threats and dangers. It also makes you more likely to construe ambiguous evidence as threatening or dangerous. By contrast, disgust disposes you to look for contaminants and impurities. And it also makes you more likely to construe ambiguous evidence as disgusting. This idea is borne out pretty well by contemporary social science, and it's also been discussed by philosophers such as Michael Brady.

Importantly, embodying one emotion is often inconsistent with embodying another emotion. For instance, it's hard to put fear and joy together, though arguably some cases of awe fit the bill. If this is right, then it's not possible to take advantage of the inquiry-motivation and heightened sensitivity of all emotions simultaneously. This is why Nietzsche recommends perspectivism, which involves cycling through a range of emotions in connection with the same object, in order to reveal as many of its (evaluative) properties as possible. That's not always easy to do; we can't just choose what emotions we experience at will. And that's why Nietzsche associates perspectivism with gaining control over one's Pro and Con, which is a distal and often social process.

3:16: Curiosity is a key virtue for the modern type – the way you analyse it it sounds like this is a philosophical drive, that modern types are inherently philosophical in that they go unceasingly after difficult, interesting questions, are never satisfied with answers, they struggle and fight with ideas all the time – and show courage in the face of these ideas – another virtue of the modern type - so are Nietzschean virtues the reason why he – and other modern types - are philosophical but philosophical in the sense of almost old-fashioned, ancient Greek style philosophical therapy of ruthlessly looking at our most repulsive facts about ourselves to fight ‘life-preserving errors’?

MA: Yeah, that's exactly the idea. Nietzsche of course doesn't think that all modern humans share his type; the last man isn't particularly philosophical. But he aims to liberate those who do share his type by showing them through his own example how to bring together a certain kind of ruthless curiosity with intellectual courage. For him, curiosity is an epistemic or -- as you say -- philosophical drive to inquire into the hardest questions. And a question can be hard in lots of ways. One is complexity. Another is availability of evidence. And Nietzsche certainly cares about these dimensions of difficulty. But he seems to think that perhaps the hardest of all is moral. We find it really hard to accept unpleasant truths about ourselves -- either as individuals or as communities. So for Nietzsche, curiosity is perhaps best expressed not in the context of physics but in the context of moral psychology, which he compares to self-vivisection. It involves ruthlessly examining the very worst, most shameful things about ourselves and our communities. And that, of course, takes a lot of courage. Interestingly, it can be seen as a radical derivative of Kant's motto of enlightenment: sapere aude. Only Nietzsche specifically focuses on having the courage to know the worst things about oneself.

3:16: What’s the virtue of ‘the pathos of distance’ and how does this link with the moral psychology of contempt and disgust?

MA: Nietzsche only uses that phrase a few times, but he consistently associates it with a disposition to feel and express the emotions of contempt and disgust. And he has plenty to say about those emotions themselves in other passages. The pathos of distance is the drive that governs these emotions, in much the same way that courage is the drive that governs fear. Now you might wonder, what possible value could such a drive have? Contempt and disgust might seem like ugly and worthless emotions. But not for Nietzsche, and the reason why relates to his valuation of curiosity. If he's right that the most challenging inquiries are the ones that lead us to accept shameful and embarrassing things about ourselves and our communities, then those inquiries are guaranteed to terminate in emotions like contempt and disgust. Indeed, this is precisely the trajectory that Zarathustra follows, when he arrives at the "great contempt" and the "great disgust." That in turn means that the inquirer needs to have well-calibrated dispositions to feel this contempt and disgust -- in other words, to have the pathos of distance. It's not the sort of thing you'd want to try without a lot of prior practice.

Nietzsche thinks that the pathos of distance gets trained up socially, by feeling contempt and disgust for (aspects of) other people and communities, but that its ultimate value lies in this well-calibrated capacity to feel and express contempt and disgust reflexively, towards (aspects of) oneself and one's community. (Incidentally, he calls his own writing a "schooling in contempt," and we can interpret this as him trying to hone the pathos of distance of his readers by getting them to experience contempt for the many people, ideas, and groups that he ridicules so mercilessly.) And those expressions in turn, he seems to think, make it possible to reshape oneself and one's community. It's hard to change unless you see that there's something wrong with yourself and also view that thing as mutable (this relates back to the theory of drives-as-virtues that we talked about before). Giving up an aspect of yourself that you see as contemptible and not fixed is Nietzsche's envisioned path to what we might call self-improvement. He often talks about it using imagery and metaphors of mountain-climbing and being a bird ('halcyon' is his preferred term).

Now, you might wonder whether this is actually borne out by, for instance, clinical psychology. As far as I know, it hasn't been investigated directly, and it might seem a bit dangerous. Nietzsche is certainly aware of that danger. What if you find out that something contemptible about yourself is immutable? Tough luck! But it certainly would be interesting to try to investigate this empirically....

3:16: A sense of humour is one of the Niezschean virtues – why is it essential in the process of opening up enquiries into the contemptible and laughable? Why is it more than just waiting for the risible moment, as you put it, and more a determination to hunt down the laughable? And is it also a way to deal with the truth given that the truths are likely to be horrible and difficult to take, not just about the world and others abut the truths about one self as well?

MA: To laugh at something is often to take it lightly -- to see it as unimportant or unworthy, or less important and less worthy than it's typically taken to be. In other words, a sense of humor is allied with the pathos of distance in governing the emotion of contempt. It also produces positive affect -- we enjoy humor. So a good sense of humor is especially valuable to the person who's engaged in curious inquiry into the most contemptible aspects of themselves. That positive affect makes the whole endeavor less painful and more attractive, so in that sense a sense of humor helps to motivate or at least make possible this kind of inquiry. Relatedly, a sense of humor can help with the self-transformation that I mentioned earlier. If you're able to laugh at some contemptible aspect of yourself, that makes it much easier to give it up. I think that Nietzsche is really onto something here. There's clearly something wrong with people who are incapable of laughing at themselves. And that incapacity is surely related to their inability to take things lightly, to take a joke, and to be willing to admit their own flaws.

3:16: Why does solitude count as a virtue of this modern type? How is it an emotion, and what does it oppose?

MA: Solitude might be Nietzsche's most innovative conception in virtue theory. When I started the book, I didn't plan to write about it at all, but some of my colleagues suggested taking a look. This is where the distant-reading method paid off. I realized that, for him, solitude is a disposition that manifests in particular in the context of intra-group and inter-group relations. The person who embodies solitude is disposed to look for, point out, and ridicule the most contemptible aspects of their ingroup, especially if it's an unelective rather than elective affinity (e.g., family, nationality). Nietzsche does this all the time, for instance when he rags on the Germans while praising other nationalities and ethnicities. In a sense, it's the collective version of what he celebrates in the pathos of distance and having a sense of humor. With those two, one is able to laugh at and ridicule (aspects of) the I . With solitude, one is able to laugh at and ridicule aspects of the we . If this is right, then what Nietzsche calls solitude isn't itself an emotion, but it's rather a disposition or drive that directs its bearer to express a particular emotion (contempt) in a particular way (at the sacred cows of their community or ingroup). It's not an easy way to become popular!

But it's also the sort of thing that could, in some cases, lead to improvement of the community, in much the same way that the pathos of distance and a sense of humor contribute to self-improvement. Additionally, we can easily link this idea all the way back to Socrates, who made it a point to go after his fellow Athenians and suffered the consequences for it. And returning to the present, I think that a lot of recent developments in global politics demonstrate how important it is to be able to criticize one's ingroup rather than treating it as sacrosanct. To put it bluntly and perhaps too optimistically, solitude is the enemy of nationalism and fascism.

3:16: You say that for Nietzsche it’s conscience that ties these virtues together – and there are different kinds of conscience, the one for the herd and then the good one and th`e bad one. Can you sketch for us these three types, and then explain why he wants to harness the bad conscience for the modern type in the service of virtue rather than eliminate it?

MA: Nietzsche seems to have three different things in mind when he refers to conscience. Conscience simpliciter is just the herd instinct: the inner imperative that tells people to do as their community expects. Thus understood, conscience is opposed to solitude. Good conscience, by contrast, is a kind of joy one tends to feel when one's drives are cooperating with one another as I talked about earlier, in the context of the unity-of-virtue thesis. It's the positive feeling one gets when one's drives are harmonizing with each other. Bad conscience manifests when someone is being cruel to themselves. It's sort of a double-edged sword. If it's applied to non-fixed aspects of oneself, it aids in the process of self-improvement I talked about in the context of the pathos of distance, self-contempt, and laughing at oneself. But if it's applied to fixed aspects of oneself, it's liable to be psychologically devastating. For that reason, bad conscience is dangerous, but it's also the tool Nietzsche associates with self-transformation. On the (extremely plausible) assumption that no one's perfect, then, the bad conscience is the scalpel needed to perform moral psychological self-vivisection.

3:16: You conclude by deflating the importance of notions of the sovereign individual, mature egoism, resentment and the will to power, finding little to support their foregrounding in Nietzschean studies and think that admiration, trust and shame are much more important, and are underdeveloped subjects needing to be examined by future scholarship. Can you say something about this new agenda you say your approach generates – and are there other subjects alongside these three that also strike you as being of importance, in particular how your reading situates Nietzsche in terms of how we might rethink how to think about him. For example, is he still a naturalistic philosopher, and what about his relationship to Kantian or Aristotelian virtue ethics?

MA: Well, I haven't followed up on those suggestions yet, so I'm not entirely sure what you'd find! My hunch, when it comes to admiration, though, is that it's sort of the obverse of contempt. Whereas contempt involves looking down critically, admiration involves looking up positively. That can lead to emulation, which itself is complicated. If we only ever emulate, we can get stuck at the level of the best available exemplar (this is the problem Nietzsche associates with monumental history). But if we emulate in a sense of one-upmanship, we might be able to surpass existing exemplars. Anthony Jensen argues that this is Nietzsche's positive view of history in Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life. But that's an early work. It would be fascinating to systematically explore what he has to say about admiration in his more mature writings. If anyone wants a list of passages to start with, feel free to email me.

Overall, I'd say that Nietzsche is an extremely perceptive philosopher of emotions, including how their function in both moral and epistemic life. Further investigations of a wider range of emotions than I touched on in the book would be really valuable. If that's on the right track, then maybe a better comparator than Kant or Aristotle would be Hume, who is also a naturalist and has rich insights into the emotions. Neil Sinhababu seems to think that Nietzsche indirectly inherited his own view of emotions from Hume. I'm a bit skeptical, but then I'm not a Hume scholar. To contrast Nietzsche with Aristotle, one obvious thing to point to is the type-relativity of Nietzsche's framework. Aristotle maybe thought that there were different virtues for men and women, and for citizens and slaves, but he doesn't countenance an enchanting abundance of types. Kant... well, the less said about Kant the better.

3:16: So virtue ethics is something that you’ve looked out beyond the Nietzschean perspective. You defend a naturalistic relational, character-trait view of virtue don’t you? Can you sketch what this entails – is it methodological or substantive or both, merely consistent with or outright derived from natural science, and hard or softly naturalistic? Are you basically a Nietzschean?

MA: Yes, I do. I think Nietzsche is very insightful when it comes to the social scaffolding of virtues. He seems to think that drives become virtues, as I described above, in many cases through self-fulfilling prophecies. People attribute a trait to someone, and if they have a drive that could with a little modification answer to that attribution, they accept it and change to make the attribution retrospectively accurate. There's some evidence in social psychology that this phenomenon is real. I wrote about that evidence in my first book, Character as Moral Fiction, but the idea comes from Nietzsche. So in that sense, I've adopted a Nietzschean view of the development of drives into virtues. But in the Antichrist, Nietzsche says that there was only ever one Christian, and he died on the cross. I sorta feel the same way about being a Nietzschean. Anyone who outright identifies as one is self-deceived at best.

What's valuable in Nietzsche is his idiosyncracy and the rare insights that idiosyncracy leads him to. He's often wrong, sometimes terribly so. When I proposed the book, I said that I'd figure out what insights he had about gender and race. There are none, which is odd and frankly disappointing given his celebration of the virtue of solitude. But when he's right he's often one of the only philosophers you can point to who got it right. And I think that the naturalistic, relational view of virtue is an example of that.

3:16: What is the division of ethics into the three projects ofnormative theory, moral psychology and moral technology meant to help clarify for us when going about defending a naturalistic ethics? I guess the last project of a ‘moral technology’ is the one we might be less familiar with – we’re kind of used to asking what’s virtuous etc, and trying to explain human conduct in moral contexts: I never thought there was more to be done but you think there is don’t you?

MA: As Marx put it, philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world, but the point is to change it. Normative theory sets goals or ideals; it describes how things and people ought to be, ought to act, ought to think (or at least better versus worse ways of being, acting, and thinking). Moral psychology is descriptive and explanatory; it describes how things and people actually are, act, and think. If that's all you've got, the most you can do is appreciate in detail how we aren't as we should be, don't do what we should, and don't think as we ought. Pretty bleak. Moral technology is more like engineering: it's about figuring out how we get from here to there, what it would take to get us closer to being, acting, and thinking as we should. (Incidentally, this is a tripartite distinction I introduced in Character as Moral Fiction.)

3:16: How do you answer anti-naturalist claims that science can’t latch onto character and that anyway when we talk about character traits we aren’t intending them to predict, explain or control behaviour but they are merely descriptive and evaluative ways of approaching a character? Another fear might be that your naturalism in the end reduces rationalisatons of behaviours, thoughts and values to an epiphenomenal status. We’re spectators of our lives where our self-reports are at best post hoc rationalizations or worse. And what becomes of the constraint that you can’t get an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’?

MA: To be frank, I don't have a lot of patience for anti-naturalism. As many virtue ethicists and epistemologists (most of them not Nietzscheans) like to point out, we use attributions of virtues and vices to predict and explain behavior. In a recent study on which I'm a co-author, we surveyed about 45,000 people in dozens of countries and found that their level of open-mindedness was either the best or one of the best predictors of whether they rejected COVID conspiracy misinformation and accepted expert consensus on the advisability of lockdowns, masking, social distancing, and other measures. That paper is now forthcoming in Nature: Communications. This seems to me to be a pretty robust example of using science to latch onto character and predict and explain (though not, in this case, control) behavior. I've also done work with philosophers and psychologists to show that people who score low on intellectual virtue are more likely to accept conspiracy theories and fake news. The anti-naturalists are welcome to say that character traits don't enable us to predict and explain behavior, but the science is against them.

Likewise, when it comes to epiphenomenalism, I don't think it's particularly persuasive. If nothing else, people are motivated to preserve their own image of themselves. So their self-attributions of various traits is likely to lead them to act in ways that make it easier for them to hold on to those self-attributions (this is something I talk about both in Character as Moral Fiction and in the Nietzsche book). If that's on the right track, then there are going to be a feedback loops between attributions of traits, on the one hand, and expressions of them, on the other hand. Maybe it's not simply the case that we say that people are courageous because they are courageous. Maybe it's also in part the case that they are courageous because that's what we tell them, which in turn leads them to want to live up to expectations. But complex causality is not the same thing as epiphenomenality.

3:16: Alongside the issue of naturalism are the controversies around demandingness and human nature. One of the issues around demandingness is that they are or may become too demanding – ought should imply can – and that too often saints seem to be what are required. A lot of the literature seems to tremble with impossibly delicate and fine grained registers that seem a long way from how I for one go about my business. And if demandingness is a problem, regarding human nature, is there a way of determining how demanding a conception of virtue is, and should be, without relying on psychological and other salient sciences?

MA: One of the problems with saints, as Susan Wolf famously pointed out, is that they are humorless. I guess this is one reason I appreciate Nietzsche, who both had and celebrated the sense of humor. It might also be that having a sense of humor makes it possible to think about incremental self-improvement and value that for its own sake, without worrying overmuch about whether you've attained the ideal.

3:16: Finally, for the interested reader here at 3:16am, are there five books other than your own that will take us further into your philosophical world?

MA: Some books that have really made an impression on me are:

(1) Caillin O'Connor, The Origins of Unfairness. Anything O'Connor touches turns to gold. This is her account of how unfair divisions of resources and labor between the sexes may have arisen and been sustained, even if everyone involved were acting rationally (from a Bayesian/game-theoretic point of view).

(2) Joe Henrich, The Weirdest People in the World. This is Henrich's magnum opus. Or it better be, because if he writes anything even longer no one will read it. I read it during my two-week quarantine on arrival in Australia last year. He argues that incest taboos in European Christianity about a millenium ago destroyed clanship trust networks and forced people to figure out new and better ways to engage in non-kinship-based elective trust relationships, which in turn led to the rise of free cities, guilds, monasteries, and so on. And that this new way of trusting accidentally fostered the Enlightenment. Wild stuff, but surprisingly persuasive.

(3) Jonathan Shay, Achilles in Vietnam. Shay was a clinical psychologist for the US Veterans' Administration. He mostly worked with veterans of the Vietnam War. In this book, he re-reads the Iliad as a story not of heroic conquest but of moral injury. I find his reflections on trust and betrayal extremely valuable; they've certainly helped me come to terms with the loss of my twin brother six years ago.

(4) Hugo Mercier, Not Born Yesterday . This is a surprisingly optimistic and persuasive book about how we learn from each other, how misinformation and disinformation spread, and how trust and distrust can be trained up.

(5) Anna Gotlib, The Moral Psychology of Sadness. This is a terrific edited volume in my series on the moral psychology of the emotions (Moral-Psychology-of-the-Emotions). Each book in the series addresses a distinct emotion. Anna's was one of the first to be published. It includes fascinating chapters on grief (is there something wrong with recovering from it too quickly?), nostalgia (how does it get harnessed by reactionary political movements?), and other topics. (I didn't write any of the chapters in this book, so I think it's not cheating to mention it.)

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

NEW: Joseph Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised