How Dylan's Songs Work

Interview by Richard Marshall

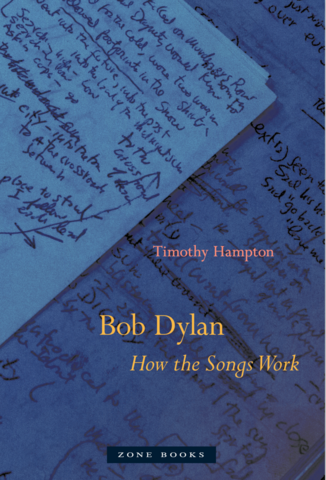

Timothy Hampton works on Renaissance and early modern European culture, in both English and the Romance languages. His research and teaching involve the relationship between politics and culture, and focus on such issues as the ideology of literary genre, the literary construction of nationhood, and the rhetoric of historiography. He regularly teaches courses on the early modern period, on travel literature, on the Baroque, on historiography, on lyric. He works on Montaigne, Tasso, Cervantes, Rabelais, Corneille, Lafayette, Shakespeare, Camões, Rimbaud, and Bob Dylan, among other authors. His most recent books are Fictions of Embassy: Literature and Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe and Bob Dylan: How the Songs Work. A new study, Cheerfulness: A Literary and Cultural History, is forthcoming from Zone Books in 2021.

3:16: Your approach to Dylan’s work resists the usual route of ‘building an edifice around the fragile core of the biography’ as you put it. You’re more interested in how he gets the job done! To give us sense of what you’re up to, can you say something about why you don’t follow the usual route and take this approach instead?

Tomothy Hampton: When I began working on the book—which was before Dylan won the Nobel Prize, by the way--I wanted to think about Dylan as an artist, as a maker of songs. It seemed to me that, whereas Dylan is usually thought of as a very clever wordsmith, these songs were extraordinarily carefully crafted in ways that had not been explored seriously. So, what does Dylan do when he makes a song? How is it put together? What is its effect? These seem to me to be questions we have to ask of any artist, from Hitchcock to Jane Austen. Yet, because Dylan works in popular song, and because we live in an age obsessed with celebrity, many listeners have a hard time separating the art from some vision of the artist’s life or personality that they have invented for themselves. This is one of the things that Dylan has complained about across his career, but it’s also just not a very interesting way of thinking about art, since it doesn’t give primacy to the work. So, my first step was to try to clear aside all of the hoopla about Dylan’s biography: his hair, his various love affairs, his medical records, his taste in shoes, etc.

3:16: What do mean when you say that Dylan is a ‘disruptor’ and why look at Dylan alone? Why not see Dylan as part of a group, or as a player in a bigger picture – rock and roll or America at a certain point of history or something like that? Aren’t you buying into the notion of white male genius from the get go by isolating him like this?

TH: Not all art is created equal. Some people make better art than other people do—just as some people are better at basketball than others are. Dylan seems to me, as an artist of song, to be working on a level that is different from most of his contemporaries. The only near equal, to my mind, is Leonard Cohen, whom Dylan once called “Number One” (Dylan described himself as “Number Zero”—that is, off the chart). So, while it would be possible to write of Dylan as “one of a group” of great, middle-class, mostly Caucasian, often Jewish, sometimes Canadian, songwriters to come out of the 1960s (Cohen, Paul Simon, Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Laura Nyro, et al), he would still demand more attention than anyone else--just by virtue of the volume and impact of the work. And, of course, to write that book would be to write a different book from the one I wrote. It would be a kind of pop culture history, or sociology. I’m interested in how art works, and in the power of aesthetic form to generate new types of experience and new types of knowledge.

In his essay on lyric poetry and society Theodor Adorno writes that individual experiences become a matter of art "only when they come to participate in something universal by virtue of the specificity they acquire in being given aesthetic form." So, the emphasis is on form, not the individual experience. He goes on to suggest that this formal aspect of art (for us, rhyme, verse form, metaphor, harmony, rhythm) is where the truly disruptive power of art lies. He says, "Immersion in what has taken individual form elevates the lyric poem to the status of something universal by making manifest something not distorted, not grasped, not yet subsumed.” This holds true doubly for song, which participates in a soundscape, while generating particular effects through form. It seemed to me that to try to keep faith with this idea of the transgressive nature of aesthetic form, I needed to look closely at Dylan’s work, not at the work of his contemporaries, and that I needed not to put him forth as one of a trend. I’m not sure that looking closely at one artist necessarily assumes “genius,” whatever that might be; it's not a word I'd ever use. And, in fact, the book is about the multiplicity of Dylan’s voices—about everything that is echoing through the songs, from Woody Guthrie to F. Scott Fitzgerald. So, in a sense, it's about a certain collectivity that speaks out through one American voice. And I make the argument early on in the book that Dylan’s professional identity—the figure of the troubadour/poet—might be seen as the response to a kind of blank spot in the field of popular music at the moment he arrived. So, I do try to locate him socially, and even commercially.

3:16: You cite Robert Pinsky to make the point about Dylan’s engagements with social, political, historical and ethical concerns when he writes: ‘ Poetry penetrates to where the body recognizes the stirring of meaning. That power is social as well as psychological. If all art is imitation what does the art of verse imitate? It imitates the social actions of mening.’ Can you say something about this in relation to how Dylan has used the lyric form for insights into social experience even after his initial overtly political phase? And can you clarify how you use lyric as fragmentation of various sorts through your study of Dylan which might be unfamiliar to readers?

TH: Lyric poems are moments of illumination, flashes of insight. When you read collections of lyrics, you move from flash to flash. Sometimes, as in, say, Shakespeare’s Sonnets, or Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, the meaning is generated through the ways poems are set next to each other. That is, the meaning is generated through the white spaces between the poems, as much as by the poems themselves. If you look at the collections of Yeats’s poems, for example, the question of where certain poems occur in the collection is part of the meaning generated by the poetry. This means that lyric meaning is closely linked to fragmentation, to a moment of significance. It contrasts with, for example, epic poetry, which tells a totalizing story, including heroes, gods, love, war, and betrayal. My sense is that Dylan uses the power of lyric to catch a single moment, or a single aspect of an experience. If we think of an early song like “One Too Many Mornings,” we see the narrator of the song caught between two moments and two places. He’s on the threshold between the room where he has lain with his lover, and the street. He’s speaking at the moment that late afternoon turns into night. Dylan uses this liminality in time and space to evoke, with great power, what is ultimately a practical problem, and ethical problem, and even epistemological problem. The practical problem is, “should I stay or should I go? What will my next step be? Back in, or out toward the wider world?” The ethical problem is, “who is right here, as this relationship seems to be disintegrating? Am I wrong to walk out?" The epistemological problem is, “who controls the knowledge we have of this situation?” which comes up in the famous—remarkably adult—lines that end the song, “you were right from your side, but I was right from mine.”

Still later, Dylan will use the power of lyric to view one aspect of a situation, and to set is against another aspect of the same situation, with the two flashes of insight in dialogue. So, on 1976’s album “Desire,” we are given the wild shaggy dog story of “Isis,” about a guy who gets married, runs away from commitment, goes through an experience of purgation in which he realizes that love is more important than gold and jewels, and returns to recommit himself to love. This song is clearly in dialogue with another song on the same disc, called “Sara,” which is one of the few clearly autobiographical moments in Dylan’s work. There we get a quite different version of a broken marriage, ending with the urgent request, “don’t ever go.” "Isis" is named after the Egyptian goddess of regeneration. "Sara" ends with the singer calling his lover "Scorpio Sphinx with an arrow and bow"--so, some combination of the mysterious Sphinx and the virgin goddess Diana. Two songs, two visions, two myths, two lyric flashes of insight—one a stylized fiction, the other some kind of autobiography or memoir.

3:16: The multilayered density of his songs is something you see as a key feature – can you say what you’re driving at here, say something about the differed layers you identify and how all this separates him from most other popular artists?

TH: Let’s just think about the title song from 1965’s “Highway 61 Revisited.” It’s an astonishing piece of writing. It opens with a sound like a police siren, but it could also be someone fooling around with a slide guitar, suggesting the electric blues. The song begins with a rockabilly beat that recalls any number of songs with silly lyrics, especially for a listener coming to this in 1965—so, “Peggy Sue, I love you,” or “Maybellene, why can’t you be true?”, or “Everbody’s gone surfin’." We expect something like that, given the groove of the song. But the opening lines are astonishing: “Well, God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son.’ Abe said, ‘Man, you must be putting me, on.’” Already we’ve got Dylan rewriting the Book of Genesis. The song clearly points to the problem of the Vietnam War, and of an older generation that would sacrifice a younger generation. But we also get God as a kind of Mafia Don, or neighborhood bully, with Abraham, the patriarch, as a parent who is, not pious before God, as the Bible says, but frightened into obeying.

Dylan is commenting on the Bible (“here’s what that bit was really about”), even as he is using the Bible to comment on current events (“here’s what’s really going on with that Vietnam business”). But he’s also commenting on the banality of the Rock and Roll, that he has just transformed with this lyric. Rock and Roll as the new Scripture. Furthermore, that opening whining sound reminds us that we are in the world of electric, Chicago-style Blues. This connects us to the title of the album, which references the highway that runs from New Orleans, past the Mississippi Delta, and up to Canada, through Dylan’s birthplace of Duluth, Minnesota. So, there’s a layer of meaning that’s about war, a layer that’s about the relationship between popular music and sacred writing, a layer that’s about the relationship of this song to the music Dylan grew up on, a layer that evokes the American history of the great migration north—and the blues that gave voice to the experience of the African Americans making that great migration. And that’s all in the first two lines! There are other kinds of complexity, to be sure, in, say, the work of the Stones or the Beach Boys, but not this kind of complexity.

3:16: You contrast Dylan with some of his contemporaries who developed influential bodies of work, people like Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell, by saying that Dylan radiates outwards rather than inwards. What are you getting at in this contrast and what does it tell us about Dylan’s interests?

TH: I was just thinking that Dylan’s imagination seems to be remarkably capacious. He absorbs things and returns them to us in his songs. So, in “You’re a Big Girl Now,” he cites the movie “Children of Paradise.” “Summer Days” is in dialogue with “The Great Gatsby,” “Dignity,” is a film noir, “Every Grain of Sand” is a reworking of a poem by Blake, and so on. This makes it possible for him to embrace a remarkable range of themes—love stories, stories of corruption, stories of wandering, stories of loss—and to draw on many genres—ballads, blues, epic, Mexican rancheros, Tin Pan Alley songs, etc. By contrast, Cohen, for all of his brilliance, is very focused. He has a couple of themes—desire, betrayal, regret, the nature of the sacred. And he works them beautifully. Mitchell’s work evolved in interesting ways, especially sonically. Her development or her own song forms, harmonies and tunings, is really impressive. But her focus on her own originality often prevents her from using the work of those who came before her. By contrast, Dylan borrows from everybody, so his work is always also about tradition and history as much as it is about his own experience.

3:16: How does Dylan use what you describe as ‘often unvarying sonic tracks’ to accompany his lyrics to establish an authority over what is happening and does this help him maintain that use of ‘I’ in his songs that enables him to dip in and out of the worlds his characters move in. And is that ‘I’ the modernist ‘I’ of Rimbaud?

TH: I think it’s interesting to contrast Dylan with the Beatles, who tried to create different sonic worlds with different songs. “Sun King” gives us a reverb-drenched guitar part that sounds like Bach slowed down. “Here Comes the Sun” is a jangly guitar, as fits the theme of the song—spring is here, time to sing. And they’ll shift instruments in the middle of a song—guitar goes away, a piano suddenly appears, here comes the French Horn. Dylan sets up a track and then fools around with his vocal delivery, speeding up the lyrics, slowing down, changing the melody from verse to verse. What, in fact, is the actual melody of, say, “Isis”? Can someone hum it for us? This makes it possible for him to jump in and out, letting the band play, singing, talking, swooping up and down the musical scale, chanting, yelling, more or less at will.

I hadn’t thought of this performative multiplicity as the modernist “I” of Rimbaud, but I think you’re right. Rimbaud says the self is multiple. Which Dylan is Dylan, in “Stuck Inside of Mobile”? The one who seems to sing a melody? The one who seems to talk at a couple of points? The guy who changes around the chorus, so that no two repetitions are the same? The one who seems to forget the words at one point in the song?

3:16: You see him as a shape shifter in the sanes that he sings certain kinds of songs at one time and then moves on to sing a different kind of song afterwards, - and he keeps doing that. So at first you say he’s singing songs as a sort of ‘poetics of adaption’ where he works with earlier models such as in the spirit of Woody Guthrie. Can you say something about this phase – what were the innovations and discoveries here? And why are Brechtian insights important here?

TH: One of the things that strikes me about Dylan’s so-called “protest” songs is that there is generally a kind of distance between what happens, and what he says about what happens. That is, whereas many songwriters might write the story of the murder of a poor black person by white racists and end by saying, “See, we’ve got to stop this stuff. Act now!” Dylan, by contrast, in “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” recounts the murder of the civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and then explores the motivations and pressures that are placed on the murderer. So, you say, “wait, I thought this was about Medgar Evers!” But it’s not, it’s about the killer, and about an entire system that turns people into murderers. That distance between the event and, for lack of a better word, the “moral of the story,” seems quite particular to Dylan’s writing. So, while he may adapt forms from other songwriters, he creates a kind of effect of irony, which asks us to think about what the form is doing, and what he’s doing with it. I suggest that the ironic perspectives that Brecht generates on the action of his plays—starting with the “Threepenny Opera”, which Dylan studied closely during this period of his career—is not irrelevant here.

3:16: You use 'Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll' to illustrate part of the new discoveries that are happening even within the ‘folk’ idiom don’t you, pointing to a new sort of complexity? What happens between his first two albums and The Times They Are A Changin and Another Side of Bob Dylan?

TH: I’m not sure. He went to England. I was recently at a conference in France, where someone gave a brilliant paper showing how Dylan’s writing changed in sophistication after he spent some time in England, where he met people like the great folksinger Martin Carthy. The songs on The Times they Are A-Changin’ reflect that, since many of them are based on English, Irish, or Scottish models—the Patriot Game underpins With God On Our Side,” for example, and "Restless Farewell" is based on "The Parting Glass." He seems to be moving away from the Woody Guthrie repertoire.

“Another Side” is a different kettle of fish. Dylan seems to have gotten bored writing about the news. So, he started writing about himself, the people around him, the little dramas of his everyday life. It’s an album that’s very interested in what my little life might have to do with the great themes and dramas of the day. So, “Chimes of Freedom” is about a guy who gets caught in a rainstorm. That’s pretty banal. But the song generates a cosmic vision of loss and redemption. That’s quite a bit different from writing songs about race riots, or lynching.

3:16: So then we get to his three ‘electric’ albums of the sixties and you identify a continuation of what you’ve called his ‘visionary poetics’ which you saw coming through as early as Another Side. So what are you getting at with this phrase and how does it work to shift and recalibrate what Dylan’s up to? Is Rimbaud a key here to what looks like a move towards being absolutely modern – more important to understand what he’s doing perhaps than anyone else? Perhaps the greatest of his creation in this phase is ‘Visions of Johanna’ so maybe you could show its visionary, Rimbaud soaked momentum?

TH: One of the problems with writing protest songs about other people’s problems is that you have to spend a lot of time telling the story. So, in “Hollis Brown,” Dylan has to set the scene, tell us where it’s happening, why Hollis Brown is miserable, what his house looks like, and so on. Starting about 1964, he starts writing in shorthand. So, in "Chimes of Freedom" he mentions “a lonesome-hearted lover with too personal a tale.” He also talks of a “mistitled prostitute.” There are entire songs in each of those lines, but he gets away with just alluding to them. From there, in about 1964-65, he gravitates to using a kind of name-dropping technique: “Ma Rainey and Beethoven once unwrapped a bedroll," "Napoleon in rags and the language that he used," "Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose.” Who are these people? We don’t actually need to know; we get the idea. It’s about creating suggestions, hints of meaning. It's much more economical than telling an entire story. It is up to the listener to fill in the blanks. This is very much like what Symbolist poets like Baudelaire and Rimbaud were doing back in the nineteenth-century. Baudelaire says “the sky is sad and beautiful like a great altar.” Could you explain that, precisely? You can’t, any more than you can figure out why there is a “guilty undertaker” in the first line of Dylan’s “I Want You.” But you get an impression. “Visions of Johanna” is a masterpiece in this genre, with these strange images of rain, ghosts, museums, memory. It’s a kind of master class in the art of suggestion.

3:16: Next you argue that Dylan switches away from the visionary poetics phase to something different again – this is a long period that starts with John Wesley Hardin and ends on the carnival road with the Rolling Thunder Review. There’s a complex of things happening in this period according to you – Petrarchan poetics of perspective and fragmentation, of ‘the brief dream’, Petrarchan degeneration into parody of its own fictions, and Romance! Can you map out what Dylan’s up to with all this – and what were the highs and lows of this turbulent period for you? I got a sense that the Levy collaborations for example on Desire were not wholly successful for you?

TH: As you point out, this is a long story, and it’s the one moment in my book at which I longed for more pages. Like many writers at the end of the 1960s, Dylan turns toward a kind of simplified approach. He turned to country music before “Country Rock” existed. John Wesley Harding offers a set of mysterious songs about escape, often with folksy proverbs to sum them up. He gives us a set of types who are no longer the pop culture names of earlier albums. Now we get the drifter, the immigrant, the messenger. And he seems to be struggling to recalibrate the relationship between private experience and public experience—all this coming, we remember, at a moment of near collapse in public life in the US. So, we have songs where the hero participates in public activities—he receives a diploma, he goes to see a famous star of some kind (in “Went to See the Gypsy”) but each scene is a disappointment. So, in his “country songs,” he turns to moments of individual enlightenment, moments of sunrise, the beauty of the sky, moonlight, etc. At a time when many artists were writing about their personal lives (John Lennon telling us the details of his marriage to Yoko, for example), Dylan was singing about moments of sacred illumination. I think of the vision of the three angels in the song “Three Angels” on New Morning.

As for “Desire,” it’s probably the Dylan album I’ve listened to most. I love every note of it. But it’s also wonderfully overdone, in a way that can only be understood as ironic, I think. After the songs of “Blood on the Tracks” which were very serious, and dealing often with recent American history, Dylan now takes us around the world, to the South Seas, in “Black Diamond Bay” (which is based on a Conrad novel), to Mexico, to the frozen north, to a gypsy camp. And at every turn there’s this kind of cheesy exoticism (“hot chili peppers in the blistering sun”) that is just excessive, like too much icing on the cake. But I love the sound of that record, with Scarlett Rivera’s violin.

3:16: What’s he doing with the male identity in his songs during this period – perhaps starting with the songs in ‘Blood on the Tracks’ are we seeing a different lyrical world being registered where masculinity is off balance?

TH: Well, we know that, biographically, Dylan’s life was in turmoil in the mid-1970s. ‘Blood on the Tracks’ is certainly some reflection of the breakup of his first marriage. But it’s also a reflection on the path he has already covered, on the 1960s, on revolution and broken dreams. So, the singing persona is, for the first time, really, in situations of weakness, uncertain of how to proceed. It’s quite powerful. Much Rock and Roll and country music has until very recently been about men who are either in hot pursuit of women, or lamenting the infidelity of those women. Dylan approaches these themes and opens them up, with a kind of acknowledgment of the limits of his own power. In “You’re gonna make me lonesome when you go,” he just accepts the situation. He doesn’t offer advice, as he did earlier, in “To Ramona,” or reproach the woman who has left him. He just recognizes that he can’t change things.

3:16: Next Dylan shifts again into songs of conversion and prophecy – these after he’d suffered a few artistic failures. You talk about penitence, odes, of things being judged and things changing – this period seems to embody a kind of fading away of his earlier confidence about his art and art generally to make a difference to the world. Is that how you see the songs of this time, which for some seems Dylan’s least interesting and successful period?

TH: Dylan’s so-called Christian Period is indeed a phase that some people have trouble liking. But I think that this is where my focus on how the songs are put together--rather than focusing on his biography--yields some good insights. I think if you look at the craft that went into those songs, you will be delighted and moved. Yet the theme of personal failure—which underpins any theology of original sin—is often countered with aggressive gestures toward listeners, accusations, condemnations. So, the songs are very uneven in their emotional texture. But worth listening to closely. I must say that this was material I had not spent a lot of time with before working on this book, and it was a revelation to me.

3:16: Dylan said around the turn of the century that he felt like he was walking through a ruin. And the albums he released about that time, beginning with “Time out of Mind” seem to have a kind of deliberately fragmentary character. The songs are loose in construction, as if it were less than obvious how to tell these stories. He sometimes seems to patch a couple of narratives onto each other—which is, of course, an old blues trick. And he starts quoting other people madly—Milton, Fitzgerald, Jimmie Rodgers, Bing Crosby. He even takes, virtually unchanged, the melodies of some Tin Pan alley songs and simply puts new words to them. And the songs are often about dispossession, about exile, about ruined lives. It’s as if he’s taking the fragments of our culture, an earlier culture that we are losing, and patching them together, holding them up for contemplation. He’s doing, in the form of his songs, what the songs are about, a kind of breakdown of coherence. This loose approach, what I called “late style” (in a phase I copped from Adorno), reflects the dissolution of the social bonds, the disappearance of good jobs, the death of the heartland—all of those factors that Trump exploited so powerfully as he rose to power. Dylan pointed to them first. When most of his contemporaries were celebrating the wonders of globalization, he knew who was suffering.

I’m not sure what to make of his recording of standards associated with Sinatra, except that “Old Blue Eyes” is gone and there’s a new blue-eyed kid in town. What I like about those records is that he takes songs originally written for orchestras and big bands and turns them into, as it were, folk songs, that anyone in a small string band can now play.

3:16: A great strength of your approach to Dylan through examining the poetic forms that have framed and informed his various evolutions and transformations is that you can show how he has been able to draw on these resources at later points, explore them, play with them and tease out new ways of seeing through them. A key to all this has been his voice which is the kind of voice that isn’t supposed to sing. How important to understanding and appreciating Dylan is recognizing the various ways he uses his voice throughout his career and what discoveries he’s made in this dimension of his work as a singer?

TH: Over the course of his career, Dylan has certainly made his listeners aware of the capacity of the human voice to change, grow, evolve, decline, and yet still make music. Of course, he is not alone in this regard--the voices of both Cohen and Mitchell became noticeably lower as they aged. Other singers stick with what works; Paul McCartney still sings with the same voice he sang with when he started, though, of course, it has aged a bit. By contrast, Dylan has gone through dozens of different voices. And one thing that comes to mind from your question is that he has also made us sensitive to the flexible border between talking and singing. Dylan's performances are often partly spoken. He rarely just talks over the music the way Elvis did on "Love Me Tender," but there is always something slightly conversational about the singing. This is why singers who cover Dylan's work by "singing" it with lots of vocal pyrotechniques and extended notes often fail to do justice to the songs. Somehow, by making it more conventionally "musical" they make it less powerful. An exception to this is Emma Swift's recent album, "Blonde on the Tracks," which offers beautiful reworkings of a number of often unappreciated songs.

3:16: Since you wrote your book Dylan’s released two more studio albums – can you say something about what is gong on with these two – are they a break from the pervious group, do they form a new phase – what resources do you find him drawing on from his previous phases and are there surprises or innovations we should be examining and appreciating further?

TH: I think that the most recent record, Rough and Rowdy Ways, is truly masterful. Dylan is confident and moves easily across a vast cultural terrain, from modernist poetry, to ancient history, to gospel, without batting an eye. He truly does, as he says in the first song on the album, "contain multitudes." And on one level, it's a record about how to write, a kind of ars poetica, I think. The songs are about creating characters, about telling the truth, about being true to yourself, about getting inspiration from the Muses—all the things you need to be a writer. They are about the relationship of history and poetry--that old Aristotelian topos. And the final song, "Murder Most Foul" is an overwhelming excursion into the death of the American Dream. When I heard it for the first time, I wept. Coming, as it did, right in the middle of the pandemic, just as Trump was spewing forth lies about the disaster all around us, it seemed as if Dylan had been able to see where we went wrong. And at the same time, the album is all about ghosts, about radio, pirates, echoes, and about how music may be, in the end, the only thing that can sustain us in these dark days. "Play Nat King Cole, play 'Nature Boy'" he has Kennedy ask of Wolfman Jack. Play Bob Dylan, say I.

3:16: And finally, as a take home, can you say which is your particular favourite Dylan song and do your thing with it and show us why it’s so?

TH: I've recently been returning to "Stuck Inside of Mobile," which is a song I don't write about in detail in my book. But it strikes me as a kind of distillation, or gathering spot, for a number of features of Dylan's writing in the 1960s. For one thing, it picks up on the old topos of the madcap, picaresque hero of some of Dylan's early "talking blues," songs, like "I Shall Be Free," or "Talkin' World War III," where we follow the protagonist from one humorous misadventure to another. Here that persona reappears, but in a much more complicated situation. He is stuck in Mobile, Alabama, a city noted for its racism--there were lynchings and KKK marches as late as the 1990s--and he longs to get to Memphis, the home of the blues, over on Highway 61. So it's partly a comment on the geography of the South, at the time of the Civil Rights Movement--on the two sides of the South, as racist graveyard and fountain of music. Here our hero finds himself in a set of stock scenarios--a wedding, a funeral, a honky tonk, and so on. In each scene he meets someone who leaves him humiliated, confused, or insulted. So it's a song about trying to find one's way through the jungle of people who want to keep you down. It's nice that it's called a blues, but that, formally, it isn't a blues (he'd have to go to Memphis for that, and he can't get there). Rather, we have this great repetition of the open sequence--a major chord leading to a minor chord--which happens three times.

We're waiting for the harmony to go somewhere else, but it keeps moving back and forth between those two first chords, as if there were no escape. But at another level the song is about communication. People give the hero messages that he can't understand. There's a French girl who think she knows him, but doesn't. He's tempted by beautiful Ruthie but caught between her and another woman. Someone gives him drugs and he misuses them. And the chorus asks at each turn if this is really all there is. Is he destined to move from one scene to another, with no escape? And yet, it's also about time and repetition. The last verse opens with the image of the street where "the neon madmen climb," some sort of image of a blinking light, moving upwards. And he concludes by asking if he'll have to go through it all again--even as he's spent the entire song asking if this is the end. So, how can both of these things be happening--reaching the end and being caught in a cycle of repetition? A repetition of the end? It sounds like something out of Nietzsche, or perhaps Groundhog Day.

But what I like most about the song is the moments of dialogue. One of Dylan's great technical innovations in songwriting is that he sets up conversations between people, often between men and women, or between friends. He stages these. This technique opens the song up, asking us to figure out which voice we want to identify with, where we want to enter the song. Conversation opens the possibility for multiple viewpoints and multiple interpretations. Which is why this might be a nice place to end the conversation I've been having with you, for which I'd like to thank you very much.

About the Interviewer

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

He has a couple of things on Dylan here and here